To the editor:

The chronic lymphocytic leukemia international prognostic index (CLL-IPI), which combines 5 parameters (age, clinical stage, TP53 status [normal vs del(17p) and/or TP53 mutation], IGHV mutational status, and serum β2-microglobulin) to predict clinical outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients was first published in 2016.1 The utility of this prognostic tool has been confirmed in independent validation studies across countries and in different practice settings (ie, academic medical centers, national population-based cohorts, and clinical trials).2-7 However, there are subtle but important differences of median survival of each risk category across series, and limited information is available on the utility of the CLL-IPI tool to predict time from diagnosis to first treatment.

To increase understanding of these important clinical questions, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) Statement, which includes all published studies that have used CLL-IPI to predict clinical outcome of CLL (PRISMA Flow Diagram; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site).8 The literature search used PubMed to identify original full-text articles and research letters published in English on the utility of the CLL-IPI reported prior to 30 June, 2017. The search strategy used both Medical Subject Headings terms and free text words to increase the sensitivity. The electronic search yielded 9 records, including 6 articles assessed for eligibility. A complementary manual search was also performed to screen the proceedings of the annual meetings of the American Society of Hematology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and European Hematology Association from the last 3 years identified 3 additional citations.9-11 Abstract evaluation and data extraction were performed by 2 reviewers (S.M. and D.G.). A crossaudit between reviewers allowed to include only studies that reported information on overall survival (OS) and/or time to first treatment (TTFT) and enrolled 100 or more patients. Data, extracted in a standardized format, included name of the study, period of enrollment, follow-up duration, median age of subjects included, time in the course of the disease at which CLL-IPI was assessed (ie, at diagnosis, at time of first treatment, and at relapse), and patient distribution into the 4 CLL risk categories in different studies (supplemental Table 1). The heterogeneity of the data was evaluated by χ2 Q test and I2 statistic. For the Q test, P < .05 indicated significant heterogeneity; for the I2 statistics, an I2 value >50% was considered significant heterogeneity.

In total, 9 studies including 7843 patients analyzed the impact of CLL-IPI on OS. Because the CLL-IPI working group applied the CLL-IPI in 4 different patient data sets (1 training data set, 1 internal validation data set, and 2 external validation data sets from the Mayo Clinic and Scandinavian series, respectively), an overall number of 12 CLL patient cohorts was considered suitable for this meta-analysis (supplemental Table 1).1 The patient distribution into the CLL-IPI risk categories was as follows: low risk (LR), median, 45.9% (range, 1.3% to 58%); intermediate risk (IR), median, 30% (range, 8.2% to 39%); high risk (HR), median, 16.5% (range, 12.6% to 56%); and very high risk (v-HR), median, 3.6% (range, 2.2% to 40.8%) (supplemental Table 1). The wide range of distribution across CLL-IPI risk categories reflects differences of the point in the course of the disease at which CLL-IPI was assessed in the different patient cohorts (ie, at diagnosis [8 series], at time of first treatment [3 series], and at relapse [1 series]).

Eleven series comprising 7383 patients had sufficient data to calculate the 5-year survival probability (supplemental Table 1), which was 92% for LR CLL-IPI (95% confidence interval [CI], 90% to 93%), 81% for IR CLL-IPI (95% CI, 80% to 83%), 60% for HR CLL-IPI (95% CI, 58% to 63%), and 34% for v-HR CLL-IPI (95% CI, 29% to 40%). Values of the Q or I2 test suggest a certain degree of heterogeneity across different studies (ie, LR, Q = 63.9, P < .001, I2 = 84%; IR, Q = 59.8, P < .001, I2 = 83%; HR, Q = 49.7, P < .001, I2 = 80%; v-HR, Q = 27.4, P = .001, I2 = 67%) (Figure 1).

Five-year survival probability on pooled meta-analysis. The analysis accounts for 7843 patients in whom CLL-IPI was applied at different points in the course of their disease (ie, at diagnosis [8 series] and time of first treatment [3 series]). SCAN, SCALE Scandinavian population-based case-control study.

Five-year survival probability on pooled meta-analysis. The analysis accounts for 7843 patients in whom CLL-IPI was applied at different points in the course of their disease (ie, at diagnosis [8 series] and time of first treatment [3 series]). SCAN, SCALE Scandinavian population-based case-control study.

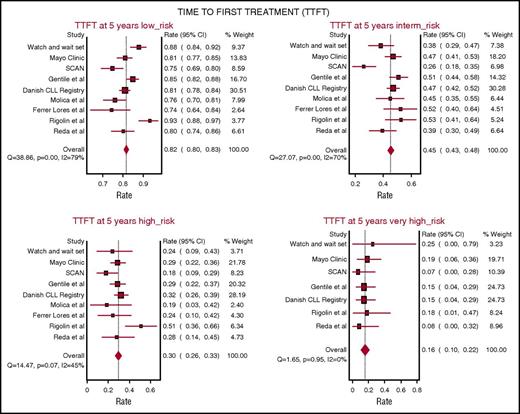

TTFT was evaluated in 7 studies including 5206 patients from 9 patient cohorts assessing CLL-IPI at diagnosis. The probability of remaining free from therapy at 5 years on pooled meta-analysis was 82% (95% CI, 80% to 83%) in the LR group, 45% (95% CI, 43% to 48%) in the IR group, 30% in the HR group (95% CI, 26% to 33%), and 16% in the v-HR group (95% CI, 10% to 22%). Notably, the heterogeneity in TTFT across different studies was greatest among patients in the LR (Q = 38.8, P < .001; I2 = 79%) and IR CLL-IPI categories (Q = 27.0, P < .001; I2 = 70%), whereas smaller variability was observed among patients in the HR (Q = 14.4, P = .57; I2 = 45%) and v-HR CLL-IPI categories (Q = 1.65, P = .95; I2 = 0%) indicating more consistent TTFT outcomes among the HR and v-HR groups across studies (Figure 2).

Five-year probability of remaining free from therapy on pooled meta-analysis. The analysis accounts for 5206 patients from 9 patient cohorts. In all patients, CLL-IPI was applied at the time of diagnosis.

Five-year probability of remaining free from therapy on pooled meta-analysis. The analysis accounts for 5206 patients from 9 patient cohorts. In all patients, CLL-IPI was applied at the time of diagnosis.

A potential confounder of this meta-analysis is that studies included evaluated the utility of the CLL-IPI at different points in the course of their disease.1-7,9-11 We therefore wondered whether the heterogeneity observed would be reduced by restricting the analysis to studies applying the CLL-IPI at the time of first diagnosis. Overall, 4893 patients in the meta-analysis (62.3% of the population) were stratified by the CLL-IPI at the time of first diagnosis and were suitable for subanalysis.1,2,4-7 Distribution of patients across different CLL-IPI categories was as follows: LR, median 51.5% (range, 42% to 58.1%); IR, median 31.2% (range, 24.9% to 38%); HR, median 16.3% (range, 9.7% to 18%); and v-HR, median 3.3% (range, 2.2% to 4.6%). Of note, a direct comparison with respect to distribution in the different CLL-IPI categories between patients evaluated at the time of diagnosis (n = 4893) and at the time of therapy or relapse (n = 2950), respectively, revealed a significantly higher number of patients belonging to HR or v-HR CLL-IPI categories in the latter cohort (P < .0001) (supplemental Table 2).

The 5-year survival probability in the subset of patients stratified by the CLL-IPI at the time of first diagnosis was 92% for LR CLL-IPI (95% CI, 91% to 93%), 83% for IR CLL-IPI (95% CI, 81% to 84%), 67% for HR CLL-IPI (95% CI, 63% to 70%), and 42% for v-HR CLL-IPI (95% CI, 35% to 51%) (supplemental Figure 2). Values of the Q or I2 test again demonstrated heterogeneity across different studies (LR, Q = 61.2, P < .001, I2 = 89%; IR, Q = 54.8, P < .001, I2 = 87%), which consistently decreased when dealing with HR and v-HR patients (HR, Q = 10.5, P < .16, I2 = 33%; v-HR, Q = 12.5, P = .05, I2 = 52%). A supplementary subanalysis limited to series applying the CLL-IPI at the time of first treatment disclosed, on the contrary, higher heterogeneity across studies in patients with HR and v-HR (supplemental Figure 3).

In addition to the CLL-IPI, other scores have also been proposed using multivariate analysis to extract relevant factors from the plethora of known prognostic markers.5,12-15 These models help to simplify CLL prognostication.

Results of this comprehensive review and meta-analysis including all studies published to date, confirm that CLL-IPI is an important step toward harmonizing international prognostication for CLL. However, although the validity of the CLL-IPI is confirmed across several series including patients mostly treated with chemoimmunotherapy, available data of patients treated with novel agents to include in this meta-analysis are limited (ie, only 1 abstract). The lack of these data to incorporate is a major limitation of the present study and jeopardizes the ability of the CLL-IPI to influence current clinical practice. The introduction of several novel therapies targeting Bruton tyrosine kinase (ie, ibrutinib), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (ie, idelalisib), and bcl2 (ie, ventoclax) has dramatically changed the therapeutic landscape and altered the natural history of CLL. Because observation remains the standard of care for asymptomatic early-stage patients, the introduction of these agents does not impact the utility of the CLL-IPI for predicting time from diagnosis to first treatment, but it likely has a profound impact on the survival of patients of all risk categories once treatment is indicated. Additional studies validating the utility of the CLL-IPI for predicting OS in patients treated with targeted therapy are needed.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M. designed the study, selected and evaluated studies, performed data extraction, evaluated and interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript; D.G. selected and evaluated studies, performed data extraction, performed statistical analyses, and evaluated results; R.M. and L.L. interpreted results; T.D.S. evaluated and interpreted results and wrote the paper; N.E.K. interpreted data and supervised the final version of manuscript; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stefano Molica, Department of Hematology-Oncology, Azienda Ospedaliera Pugliese-Ciaccio, Viale Pio X, 88100 Catanzaro, Italy; e-mail: smolica@libero.it.

![Figure 1. Five-year survival probability on pooled meta-analysis. The analysis accounts for 7843 patients in whom CLL-IPI was applied at different points in the course of their disease (ie, at diagnosis [8 series] and time of first treatment [3 series]). SCAN, SCALE Scandinavian population-based case-control study.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/131/3/10.1182_blood-2017-09-806034/4/m_blood806034f1.jpeg?Expires=1769109856&Signature=R4lMmr9KIis1EaU0pwV-AYx68EyEwwl0zwgmENR88Bpf8CsQBG-hB6JJa33FfwRYniGyaTIj4gLCb3jqW1Mx5G~uOvgB9zKQKQg9TU5wlTsSUIH1RrFKFBcVAxXQsPuumVf24WDYKNmvTFFQh0Cs423zLUT6kdPFLbxIFlwwZ8bmUV8fx3xoNxw9aaAUL4OOWVOkXCzpCfvP-wAyivNyoujYIoYSuRLENyaUQqZFhMANL39jVSO8RVTUGOIyJON3IO7nrcgbCjeZUWP~fxO~k8-vqrSck0EFaSuMD5MdhobnQg5sI-6QVh31U-AaMOBP87iaxSKiZ2rCM1ZQnsw0fw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)