Key Points

Leukemic cells in an inv(3)(q21q26) EVI1 misexpression mouse model are able to differentiate toward myeloid lineage.

Gata2 heterozygous deletion accelerates EVI1 misexpression leukemia by inducing a proliferation and differentiation defect in leukemia cells.

Abstract

Chromosomal rearrangements between 3q21 and 3q26 induce inappropriate EVI1 expression by recruiting a GATA2-distal hematopoietic enhancer (G2DHE) to the proximity of the EVI1 gene, leading to myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The acquisition of G2DHE by the EVI1 gene reciprocally deprives this enhancer of 1 of the 2 GATA2 alleles, resulting in a loss-of-function genetic reduction in GATA2 abundance. Because GATA2 haploinsufficiency is strongly associated with MDS and AML, we asked whether EVI1 misexpression and GATA2 haploinsufficiency both contributed to the observed leukemogenesis by using a 3q21q26 mouse model that recapitulates the G2DHE-driven EVI1 misexpression, but in this case, it was coupled to a Gata2 heterozygous germ line deletion. Of note, the Gata2 heterozygous deletion promoted the EVI1-provoked leukemic transformation, resulting in early onset of leukemia. The 3q21q26 mice suffered from leukemia in which B220+ cells and/or Gr1+ leukemic cells occupied their bone marrows. We found that the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population contained leukemia-initiating cells and supplied Gr1+ leukemia cells in the 3q21q26 leukemia. When Gata2 expression levels in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells were decreased as a result of Gata2 heterozygous deletion or spontaneous phenomenon, myeloid differentiation of the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells was suppressed, and the cells acquired induced proliferation as well as B-lymphoid–primed characteristics. Competitive transplantation analysis revealed that Gata2 heterozygous deletion confers selective advantage to EVI1-expressing leukemia cell expansion in recipient mice. These results demonstrate that both the inappropriate stimulation of EVI1 and the loss of 1 allele equivalent of Gata2 expression contribute to the acceleration of leukemogenesis.

Introduction

Chromosomal reciprocal translocation and inversion between 3q21 and 3q26 are well-known causes underlying myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) referred to as 3q21q26 syndrome.1 In cells harboring the translocation or inversion, the MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus (MECOM) gene located on 3q26 is misexpressed in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). The EVI1 gene (a short-form of the MECOM gene) encodes the transcription factor EVI1, which is highly expressed in hematopoietic stem cells and plays essential roles in the maintenance of stem cells.2,3 Forced EVI1 expression in bone marrow cells by retrovirus transduction has been shown to cause leukemia in mice,4 leading to the conclusion that EVI1 misexpression is a major cause of leukemogenesis. However, the mechanisms underlying this form of leukemogenesis that is provoked by these chromosomal rearrangements remain incompletely understood.

We and others recently identified a GATA2 distal hematopoietic enhancer (G2DHE) that induces elevated EVI1 gene expression from the rearranged allele.5,6 G2DHE resides approximately 100 kb upstream of the human GATA2 gene located at 3q21. Because the breakpoint cluster of the chromosomal rearrangements between 3q21 and 3q26 resides between G2DHE and the GATA2 gene, after 3q21q26 rearrangement, the G2DHE becomes separated from GATA2 and is then found in much closer proximity to the EVI1 gene, so that instead of regulating GATA2 transcriptional activity, G2DHE now induces EVI1 misexpression in HSPCs.5 Of potentially critical importance, acquisition of G2DHE by the EVI1 gene reciprocally deprives this locus of 1 of the 2 active GATA2 alleles as a direct consequence of the rearrangement. Therefore, the abundance of GATA2 should also be diminished in leukemia cells with 3q21 rearrangements when compared with autosomes lacking the 3q21 rearrangements.6,7

GATA2 is a transcription factor that is expressed abundantly in HSPCs.8-12 Of interest, GATA2 haploinsufficiency has been shown to be associated with myeloid leukemogenesis. For example, germ line mutations of GATA2 have been found in human hematologic disorders associated with MDS and AML such as the syndrome of dendritic cell, monocyte, B, and natural killer lymphoid deficiency13 ; monocytopenia/Mycobacterium avium complex (MonoMAC) syndrome14 ; Emberger’s sydrome15 ; and familial MDS or AML.16 The gene mutations found in these diseases seem to cause loss of GATA2 function and GATA2 haploinsufficiency.17 In addition, reduced GATA2 expression levels caused by mutations in presumptive regulatory regions of the gene have also been observed in MonoMAC patients.18 These observations led us to hypothesize that GATA2 haploinsufficient loss of function (LOF) might be a cooperating determinant for leukemogenesis in cells harboring translocation or inversion between 3q21 and 3q26.

We recently generated a 3q21q26 model mouse line bearing a transgene construct that recapitulates the human inv(3)(q21q26) allele. The inv(3)(q21q26) allele was generated by linking 2 bacterial artificial chromosome clones containing the G2DHE regulatory element placed in close proximity to the EVI1 gene.5 We found that the human EVI1 transgene is expressed preferentially in HSPCs of the 3q21q26 mice, and that those mice develop leukemia after 24 weeks of age, demonstrating that EVI1 expression is a dominant cause of the 3q21q26 leukemia. Thus, the 3q21q26 mice emerged as an excellent model system for studying leukemogenesis, but this mouse has 1 prominent problem as a precise model for human pathophysiology: both of the endogenous murine Gata2 genes retain G2DHE, and thus the expression of GATA2 is not altered in the tissues and organs of the 3q21q26 mice as it is in their human disease counterpart.

To elucidate the detailed mechanisms connecting the possible contribution of Gata2 haploinsufficiency to the disease phenotype, we generated compound mutant mice bearing the 3q21q26 bacterial artificial chromosome transgene and one Gata2 null mutant allele (3q21q26::Gata2+/−) to recapitulate both the EVI1 misexpression and Gata2 heterozygous LOF in human patients. Of note, the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− compound mutant mice developed leukemia significantly faster than did the 3q21q26 mice. These results unequivocally demonstrate that the Gata2 haploinsufficiency critically contributes to the progression of 3q21q26 leukemogenesis.

Methods

Mice

3q21q26 mice (line B)5 and Gata2+/− mice12 have been described previously and were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. 3q21q26 mice have been deposited at the RIKEN BioResource Center (RBRC09508). All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee at Tohoku University. Mouse analysis methods are described in supplemental Data, available on the Blood Web site.

Statistical analysis

Bar graphs in all figures are represented as mean ± standard deviations. The horizontal lines within the box plots indicate the median. Boundaries of the boxs indicate the upper and lower quartile. The whiskers indicate 1.5 × interquartile ranges. Student t test (two-tailed) was used to calculate statistical significance (P). The log-rank statistic was used to test whether the survival distributions differed between groups. Statistical significance is indicated by *P < .05 or **P<.01.

Results

Loss of 1 Gata2 allele in HSPCs promotes accelerated leukemia development in 3q21q26 mice

To analyze the influence of Gata2 heterozygous deletion on the leukemogenesis associated with 3q chromosomal rearrangements, we crossed the 3q21q26 mice with Gata2 heterozygous knockout (Gata2+/−) mice to generate compound mutant (3q21q26::Gata2+/−) mice (Figure 1A). The 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice were born in an expected Mendelian ratio and grew normally. To test the hypothesis that Gata2 haploinsufficiency might affect the leukemia transformation in the 3q21q26 mice, we next examined cohorts of wild-type (WT), Gata2+/−, 3q21q26, and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice for the onset of leukemia. We examined hematologic indices of the peripheral blood on a regular basis, and euthanized mice that exhibited white blood cell counts greater than 5 × 104/μL (our approved humane animal welfare limit for definition of mice with frank leukemia). Consistent with our previous study,5 postnatal 3q21q26 mice developed leukemia after approximately 200 days (Figure 1B), and blast cells were observed in peripheral blood of these mice (Figure 1C). The 3q21q26 mice exhibited several leukemic phenotypes, including anemia, thrombocytopenia (Figure 1D), splenomegaly (Figure 1E), and infiltration of leukocytes into the liver and lung (Figure 1F). Although the phenotypes in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− and the 3q21q26 mice were comparable (Figure 1D-F), the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice exhibited leukemia onset significantly earlier than did the 3q21q26 mice (Figure 1B). These results support the contention that Gata2 haploinsufficiency promotes early transformation to leukemia in the 3q21q26 mice.

Gata2 haploinsufficiency promotes leukemogenesis of 3q21q26 mice. (A) Schema of mating strategy. The numbers (percentages) of pups at weaning that bear the 4 possible genotypes is depicted. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT (n = 22; median, not determined), Gata2+/− (n = 22; median, not determined), 3q21q26 (n = 19; median, 345 days), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (n = 15; median, 276 days) mice. (C) Representative smears of peripheral blood taken from leukemic 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice and age-matched healthy WT and Gata2+/− mice. (D) White blood cell, red blood cell, and platelet counts in the peripheral blood of WT (n = 13), Gata2+/− (n = 11), 3q21q26 (n = 15), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (n = 14) mice. (E) Average spleen weights (left) from WT (bar 1 [n = 13]), Gata2+/− (bar 2 [n = 11]), 3q21q26 (bar 3 [n = 15]), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (bar 4 [n = 14]) mice. Representative spleens from WT, Gata2+/−, leukemic 3q21q26, and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice are shown in right panel. Scale bar, 1 cm. (F) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the liver and lung from WT, Gata2+/−, leukemic 3q21q26, and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice. Parameters of the box plot are defined within the Statistical analysis paragraph in “Methods.” *P < .05; **P < .01.

Gata2 haploinsufficiency promotes leukemogenesis of 3q21q26 mice. (A) Schema of mating strategy. The numbers (percentages) of pups at weaning that bear the 4 possible genotypes is depicted. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT (n = 22; median, not determined), Gata2+/− (n = 22; median, not determined), 3q21q26 (n = 19; median, 345 days), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (n = 15; median, 276 days) mice. (C) Representative smears of peripheral blood taken from leukemic 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice and age-matched healthy WT and Gata2+/− mice. (D) White blood cell, red blood cell, and platelet counts in the peripheral blood of WT (n = 13), Gata2+/− (n = 11), 3q21q26 (n = 15), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (n = 14) mice. (E) Average spleen weights (left) from WT (bar 1 [n = 13]), Gata2+/− (bar 2 [n = 11]), 3q21q26 (bar 3 [n = 15]), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (bar 4 [n = 14]) mice. Representative spleens from WT, Gata2+/−, leukemic 3q21q26, and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice are shown in right panel. Scale bar, 1 cm. (F) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the liver and lung from WT, Gata2+/−, leukemic 3q21q26, and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice. Parameters of the box plot are defined within the Statistical analysis paragraph in “Methods.” *P < .05; **P < .01.

The 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells have distinct differentiation patterns

To assess the phenotypic properties of the bone marrow populations in the 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice, we first examined the expression profiles of cell surface markers by using flow cytometry. We found that in the leukemic 3q21q26 mice, both B220+ cells and Gr1+ cells were independently expanded. In 54 of 60 leukemic 3q21q26 mice, B220 single-positive cells, Gr1 single-positive cells, and B220/Gr1 double-positive cells accounted for more than 80.0% of total bone marrow hematopoietic cells (Figure 2A, left panel, yellow area). However, the proportions of these cells in individual leukemic bone marrows were highly variable. We therefore classified the leukemia in these mice into 4 types (Type I, II, III, or Unclassified) on the basis of the relative proportions of B220+ and/or Gr1+ cells. We defined Type I leukemia as those in which more than 80.0% of the bone marrow cells were B220 single-positive, whereas Type II leukemic mice harbored both B220+ cells and Gr1+ cells, and the percentage of B220 single-positive cells was between 40.0% and 80.0%. In contrast, Gr1+ cells were preferentially expanded in Type III leukemic mice, and the percentage of B220 single-positive cells was less than 40.0%. Using these classification criteria, 26.7%, 30.0%, and 33.3% of all mice were categorized with either Type I, II, or III leukemia, respectively, in the 3q21q26 cohort (Figure 2A, left panel). The remaining mice (10.0%) were categorized as Unclassified. Representative flow cytometry profiles of Type I, II, III, and Unclassified 3q21q26 leukemic mice are shown in Figure 2B.

The 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/−leukemia cells exhibit 2 distinct differentiation patterns. (A) Percentages of B220+Gr1– cells vs Gr1+ cells (B220+Gr1+ cells plus B220–Gr1+ cells) in bone marrows of the leukemic 3q21q26 (left panel [n = 60]) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (right panel [n = 32]) mice. We classified the leukemias into 4 types; Type I, II, III, and Unclassified based on the percentages of B220+Gr1– cells and Gr1+ (ie, B220+Gr1+ and B220–Gr1+) cells. The yellow-shaded area in both graphs indicates a range in which more than 80.0% of the leukemic bone marrow cells are both B220+ and Gr1+. The numbers of mice categorized into each type and their percentages are shown below the graphs. (B) Representative flow cytometric profiles of the bone marrows from Type I, II, III, and Unclassified leukemic 3q21q26 mice. (C) Representative smears of peripheral blood taken from Type I, II, III, and Unclassified leukemic 3q21q26 mice. (D) Percentages of c-Kit-positive cells in the bone marrow of the 3q21q26 Type I (n = 16), II (n = 18), III (n = 20), and Unclassified (n = 6) leukemia mice and the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 12), II (n = 2), III (n = 5), and Unclassified (n = 10) leukemia mice. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT mice transplanted with 3q21q26 Type I (n = 20; median, 28.0 days), II (n = 31; median, 38.5 days), and III (n = 28; median, 69.0 days) or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 36; median, 23.5 days) leukemic whole bone marrow cells (0.5 to 1 × 106 cells).

The 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/−leukemia cells exhibit 2 distinct differentiation patterns. (A) Percentages of B220+Gr1– cells vs Gr1+ cells (B220+Gr1+ cells plus B220–Gr1+ cells) in bone marrows of the leukemic 3q21q26 (left panel [n = 60]) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (right panel [n = 32]) mice. We classified the leukemias into 4 types; Type I, II, III, and Unclassified based on the percentages of B220+Gr1– cells and Gr1+ (ie, B220+Gr1+ and B220–Gr1+) cells. The yellow-shaded area in both graphs indicates a range in which more than 80.0% of the leukemic bone marrow cells are both B220+ and Gr1+. The numbers of mice categorized into each type and their percentages are shown below the graphs. (B) Representative flow cytometric profiles of the bone marrows from Type I, II, III, and Unclassified leukemic 3q21q26 mice. (C) Representative smears of peripheral blood taken from Type I, II, III, and Unclassified leukemic 3q21q26 mice. (D) Percentages of c-Kit-positive cells in the bone marrow of the 3q21q26 Type I (n = 16), II (n = 18), III (n = 20), and Unclassified (n = 6) leukemia mice and the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 12), II (n = 2), III (n = 5), and Unclassified (n = 10) leukemia mice. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT mice transplanted with 3q21q26 Type I (n = 20; median, 28.0 days), II (n = 31; median, 38.5 days), and III (n = 28; median, 69.0 days) or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 36; median, 23.5 days) leukemic whole bone marrow cells (0.5 to 1 × 106 cells).

Similar analyses were conducted for the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (Figure 2A, right panel). We found that 65.7% (21 of 32) of the leukemic 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice were identifiable as Type I, II or III leukemias and 34.3% as Unclassified (Figure 2A, right panel). Of note, among the mice classified as having Type I to III leukemia, the incidence of Type I leukemia was significantly increased, whereas the incidences of Type II and III were significantly diminished in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mouse cohort when compared with the 3q21q26 cohort. This result suggests that the differentiation pattern of 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mouse leukemia cells differs qualitatively from that of the 3q21q26 leukemia cells.

Type I leukemic bone marrow harbors robust leukemia-inducing capacity

To better characterize the Type I to III leukemias, we next examined cell morphologies. Wright-Giemsa staining of peripheral blood smears showed that Type I leukemia blast-like cells were highly enriched in both 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice, whereas Type II and III leukemias contained abundant differentiated cells with segmented nuclei (Figure 2C and data not shown). Similar staining of peripheral blood smears from Unclassified-type leukemia mice showed a variety of cell types and stages of differentiation that varied from mouse to mouse; an example of an Unclassified leukemia from a 3q21q26 mouse is shown in Figure 2C. Furthermore, Type I leukemic cells from both 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice contained abundant c-Kit+ cells (as did some Type II leukemic cells; Figure 2D), indicating that immature blast cells abundantly accumulate in Type I (but only marginally in Type II) leukemic mice.

To examine the leukemia-inducing ability of the bone marrow cells after transfer from Type I, II, and III leukemic animals, we performed transplantation analyses. When transplanted into sublethally irradiated WT mice, whole bone marrow cells of Type I leukemias induced leukemia onset in transplanted animals earlier than in those transplanted with either Type II or III bone marrows (Figure 2E), indicating that bone marrow cells of Type I leukemias contain blast cells that can induce early onset of leukemia. The mice receiving Type I leukemic whole bone marrow cells from the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice developed leukemia with shorter latency than the mice receiving Type I whole bone marrow cells from 3q21q26 mice, indicating that 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic bone marrow cells harbor more robust leukemia reconstitution ability.

B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells contain leukemia-initiating cells

Because the c-Kit+ cell percentages were highly correlated with the B220+ percentages in both 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic mice, we examined the expression of c-Kit in 3 different populations (B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+). We found that the B220+Gr1– population contained the most abundant c-Kit+ cells compared with B220+Gr1+ and B220–Gr1+ populations in 3q21q26 leukemic mice (Figure 3A, left panel and B). We also observed abundant c-Kit+ cells in the B220+Gr1– population from 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic mice, which were composed almost exclusively of the B220+Gr1– phenotype population (Figure 3A, right panel). Wright-Giemsa staining showed that the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ populations in both 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic mice contained blast-like cells, whereas the B220+Gr1+ and B220–Gr1+ populations in the 3q21q26 leukemic mice bore more mature cells harboring segmented nuclei and cytoplasmic granules (Figure 3C).

B220+Gr1–c-Kit+cells contain leukemia-initiating cells. (A) Representative flow cytometric profiles of c-Kit in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions of leukemic 3q21q26 (left) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (right) mouse bone marrows. Note that the B220+Gr1– fraction is predominant in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice in right panel. (B) Percentages of c-Kit+ cells in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions in the bone marrow of the leukemic 3q21q26 mice (n = 35) and the B220+Gr1– fraction in the leukemic 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (n = 15). Parameters for the box plots are defined in the Statistical analysis paragraph of “Methods.” (C) Wright-Giemsa staining of leukemic cells in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions from the leukemic 3q21q26 and B220+Gr1– fraction from the leukemic 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (c-Kit+ [top line] and c-Kit− [bottom line]). (D) Colony-forming ability of B220+Gr1–c-Kit+, B220+Gr1+c-Kit+, B220–Gr1+c-Kit+, B220+Gr1–c-Kit–, B220+Gr1+c-Kit– and B220–Gr1+c-Kit– populations from the leukemic 3q21q26 mice (n = 6). Representative colony morphologies from the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+, B220+Gr1+c-Kit+, and B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ populations are shown in the right panels. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice receiving B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ (n = 16; median, 56 days), B220+Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 8; median, not determined), and B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 6; median, not determined) cells. (F) Representative flow cytometric patterns of leukemic cells in donor mice and donor-derived (CD45.1 homozygous or CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygous) leukemic cells in recipient mice receiving B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells. (G) Relative expression levels of human EVI1 messenger RNA (mRNA) (left panel), total (human + mouse) EVI1 mRNA (middle panel), and mouse endogenous Gata2 mRNA (right panel) in B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ (n = 6), B220+Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 5), B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 4), B220+Gr1–c-Kit– (n = 4), B220+Gr1+c-Kit– (n = 3), and B220–Gr1+c-Kit– (n = 3) populations. Bar graphs represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). *, P < .05; **, P < .01.

B220+Gr1–c-Kit+cells contain leukemia-initiating cells. (A) Representative flow cytometric profiles of c-Kit in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions of leukemic 3q21q26 (left) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (right) mouse bone marrows. Note that the B220+Gr1– fraction is predominant in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice in right panel. (B) Percentages of c-Kit+ cells in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions in the bone marrow of the leukemic 3q21q26 mice (n = 35) and the B220+Gr1– fraction in the leukemic 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (n = 15). Parameters for the box plots are defined in the Statistical analysis paragraph of “Methods.” (C) Wright-Giemsa staining of leukemic cells in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions from the leukemic 3q21q26 and B220+Gr1– fraction from the leukemic 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (c-Kit+ [top line] and c-Kit− [bottom line]). (D) Colony-forming ability of B220+Gr1–c-Kit+, B220+Gr1+c-Kit+, B220–Gr1+c-Kit+, B220+Gr1–c-Kit–, B220+Gr1+c-Kit– and B220–Gr1+c-Kit– populations from the leukemic 3q21q26 mice (n = 6). Representative colony morphologies from the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+, B220+Gr1+c-Kit+, and B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ populations are shown in the right panels. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice receiving B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ (n = 16; median, 56 days), B220+Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 8; median, not determined), and B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 6; median, not determined) cells. (F) Representative flow cytometric patterns of leukemic cells in donor mice and donor-derived (CD45.1 homozygous or CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygous) leukemic cells in recipient mice receiving B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells. (G) Relative expression levels of human EVI1 messenger RNA (mRNA) (left panel), total (human + mouse) EVI1 mRNA (middle panel), and mouse endogenous Gata2 mRNA (right panel) in B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ (n = 6), B220+Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 5), B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 4), B220+Gr1–c-Kit– (n = 4), B220+Gr1+c-Kit– (n = 3), and B220–Gr1+c-Kit– (n = 3) populations. Bar graphs represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). *, P < .05; **, P < .01.

We next performed colony assays on the sorted B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ blast-like cells as well as the other cell populations of the 3q21q26 Type II and III leukemias in the presence of stem cell factor, interleukin 3, interleukin 6, and erythropoietin to examine their potential for replication. We detected high colony numbers in both B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ and B220+Gr1+c-Kit+ populations (Figure 3D, left panel). Importantly, colonies from the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population were significantly larger than those from the other populations (Figure 3D, right panels), indicating that higher numbers of colony-forming cells reside in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population and that those cells also have the most potent potential for replication.

To assess the leukemic potential of these cells in vivo, we transplanted 5 × 104 B220+Gr1–c-Kit+, B220+Gr1+c-Kit+, or B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ cells from the 3q21q26 Type II and III leukemic mice into sublethally (6 Gy) irradiated C57BL/6 mice. Significantly, mice receiving the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells developed leukemia with latencies of approximately 30 to 70 days after transplantation, whereas mice receiving an equal number of B220+Gr1+c-Kit+ or B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ cells failed to develop leukemia (Figure 3E), demonstrating that the most abundant leukemia-initiating cells reside in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population. Flow cytometry analysis of the bone marrow from mice transplanted with B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells showed that leukemic cells contained donor-derived B220–Gr1+ cells in addition to the B220+Gr1– cells (Figure 3F, lower panel), supporting the contention that B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from 3q21q26 leukemic mice can differentiate into Gr1+ leukemia cells in vivo.

The abundance of the human EVI1 messenger RNA as well as total (human plus mouse) EVI1 expression in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population were higher than in the other populations, and EVI1 expression faded to very low levels in the Gr1+ populations of Type II and III leukemic 3q21q26 bone marrow cells (Figure 3G, left and middle panels). We also found that the expression of endogenous Gata2 closely matched the levels of EVI1 (Figure 3G, right panel). These results show that the cell population expressing the most abundant EVI1 and Gata2 contain the leukemia-initiating cells.

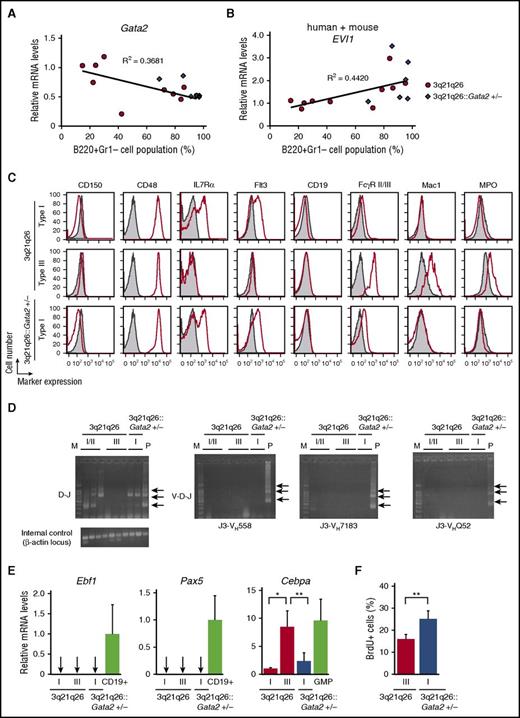

Gata2 LOF changes the character of B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells

Because the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice most often developed a Type I leukemia, we hypothesized that Gata2 abundance might vary from mouse to mouse in the 3q21q26 genetic background and that this might correlate with the leukemia types. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the Gata2 expression levels in individual 3q21q26 leukemic mice. Of note, we found that Gata2 abundance in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population negatively correlated with the percentage of B220 single-positive cells in the leukemic 3q21q26 bone marrow (Figure 4A). Gata2 levels in Type I leukemia were approximately half those in Type III leukemia; the former GATA2 abundance in turn was close to that of the Type I leukemia documented in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (Figure 4A). In contrast, the EVI1 messenger RNA abundance in B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells was higher in Type I leukemic cells than in Type III leukemic cells (Figure 4B). These results indicate that Gata2 abundance determines the myeloid differentiation potential as well as EVI1 expression levels, which result in the distinct leukemia phenotypes observed in 3q21q26 mice.

B220+Gr1–c-Kit+leukemic populations differ in phenotypic characteristics as a consequence of Gata2 haploinsufficiency. (A-B) Correlation between the percentage of B220+Gr1– cell populations in the bone marrows and expression levels of mouse endogenous Gata2 (A) and total (human + mouse) EVI1 (B) mRNAs in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells of 3q21q26 (n = 10) or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (n = 6) mice. The abundance of Gata2 and total (human + mouse) EVI1 mRNAs was normalized to Gapdh abundance. Average values for the 3q21q26 Type III leukemic mice were set to 1. Linear approximations and R2 values of the 3q21q26 leukemic mice are shown. (C) Representative flow cytometric profiles of CD150, CD48, IL7Rα, Flt3, CD19, FcγR II/III, Mac1, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ bone marrow cells from leukemic 3q21q26 Type I (upper panels) and III (middle panels) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (lower panels) mice (red lines). Negative (unstained) control samples are shown in gray. (D) D-J and V-D-J rearrangements in B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells of the 3q21q26 Type I and III leukemia and the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I leukemia. Arrows indicate the position of amplified fragments of ∼1033, ∼716, or ∼333 bp (D-J rearrangements) or ∼1058, ∼741, or ∼358 bp (V-D-J rearrangements) using primer pairs J3-VH558, J3-VH7183, and J3-VHQ52 (see supplemental Data). M and P indicate lanes loaded with a DNA marker or a positive control (polymerase chain reaction products from genomic DNA of WT mouse CD19+ cells). (E) Expression levels of Ebf1 (left panel), Pax5 (center panel) and Cebpa mRNA (right panel) in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from 3q21q26 Type I (n = 3), Type III (n = 4), or the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 6) leukemic mice. CD19+ B cells and granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP) cells in WT mice are used for positive controls of Ebf1 and Pax5 and as a positive control for Cebpa expression, respectively. The abundance of each mRNA was normalized to Gapdh. Average values for the 3q21q26 Type I leukemic mice were set to 1. Arrows indicate undetectable or slight expression levels. (F) The percentages of BrdU+ cells in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population of the 3q21q26 Type III (n = 3) or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 6) leukemic bone marrows. B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells were analyzed 2 hours after intraperitoneal injection of BrdU. Bar graphs represent mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01.

B220+Gr1–c-Kit+leukemic populations differ in phenotypic characteristics as a consequence of Gata2 haploinsufficiency. (A-B) Correlation between the percentage of B220+Gr1– cell populations in the bone marrows and expression levels of mouse endogenous Gata2 (A) and total (human + mouse) EVI1 (B) mRNAs in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells of 3q21q26 (n = 10) or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (n = 6) mice. The abundance of Gata2 and total (human + mouse) EVI1 mRNAs was normalized to Gapdh abundance. Average values for the 3q21q26 Type III leukemic mice were set to 1. Linear approximations and R2 values of the 3q21q26 leukemic mice are shown. (C) Representative flow cytometric profiles of CD150, CD48, IL7Rα, Flt3, CD19, FcγR II/III, Mac1, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ bone marrow cells from leukemic 3q21q26 Type I (upper panels) and III (middle panels) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (lower panels) mice (red lines). Negative (unstained) control samples are shown in gray. (D) D-J and V-D-J rearrangements in B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells of the 3q21q26 Type I and III leukemia and the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I leukemia. Arrows indicate the position of amplified fragments of ∼1033, ∼716, or ∼333 bp (D-J rearrangements) or ∼1058, ∼741, or ∼358 bp (V-D-J rearrangements) using primer pairs J3-VH558, J3-VH7183, and J3-VHQ52 (see supplemental Data). M and P indicate lanes loaded with a DNA marker or a positive control (polymerase chain reaction products from genomic DNA of WT mouse CD19+ cells). (E) Expression levels of Ebf1 (left panel), Pax5 (center panel) and Cebpa mRNA (right panel) in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from 3q21q26 Type I (n = 3), Type III (n = 4), or the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 6) leukemic mice. CD19+ B cells and granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP) cells in WT mice are used for positive controls of Ebf1 and Pax5 and as a positive control for Cebpa expression, respectively. The abundance of each mRNA was normalized to Gapdh. Average values for the 3q21q26 Type I leukemic mice were set to 1. Arrows indicate undetectable or slight expression levels. (F) The percentages of BrdU+ cells in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population of the 3q21q26 Type III (n = 3) or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 6) leukemic bone marrows. B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells were analyzed 2 hours after intraperitoneal injection of BrdU. Bar graphs represent mean ± SD. *P < .05; **P < .01.

To further characterize the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population in Type I and III leukemias of 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice, we analyzed the expression of immature hematopoietic cell surface markers. The B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ populations in Type I and III leukemias were both CD48+CD150–, suggesting that the population is progenitor-like rather than stem cell-like (Figure 4C).19

Closer examination revealed that the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population in Type I leukemia was positive for some lymphoid progenitor cell markers (IL7Rα and Flt3) but negative for the committed B-cell marker CD19. We detected D-J rearrangements of the immunoglobulin H (IgH) gene in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population in the Type I leukemias, but V-D-J rearrangements were not observed (Figure 4D). Expression of Ebf1 and Pax5, master regulators of B-cell lineage development, were undetectable (Figure 4E). These results indicate that the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population in Type I leukemic cells retains some characteristics of both lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor (c-Kit+Flt3+), common lymphoid progenitor (c-KitlowIL7Rα+), and pre-pro B cells.20,21

In contrast to the Type I cells, the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population of Type III leukemias expressed myeloid markers (FcγR II/III+Mac1+) (Figure 4C). In addition, we detected myeloperoxidase expression in Type III leukemic B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells but not in Type I cells. The expression of the key myeloid regulator Cebpa in Type III cells was higher than in Type I cells and was comparable to the granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells of WT mice (Figure 4E).22 These results indicate that the Type III B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells exhibit a granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (c-Kit+FcγR II/III+)-like phenotype. Of interest, the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ populations from both Gata2 heterozygous and WT 3q21q26 Type I leukemic mice showed similar patterns of surface marker expression, suggesting that GATA2 abundance determines the character of B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells.

To examine the proliferation of the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population in the 3q21q26 Type III and the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I leukemias, we performed 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assays. We injected BrdU into leukemia cell–transplanted mice that had reached circulating levels of leukemic cells >5 × 104/μL. We detected BrdU incorporation by flow cytometry and found that BrdU-positive cells were more abundant in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells in 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I leukemia (Figure 4F), indicating increased proliferation of 3q21q26::Gata2+/− B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ Type I leukemic cells when compared with the 3q21q26 Type III leukemic cells.

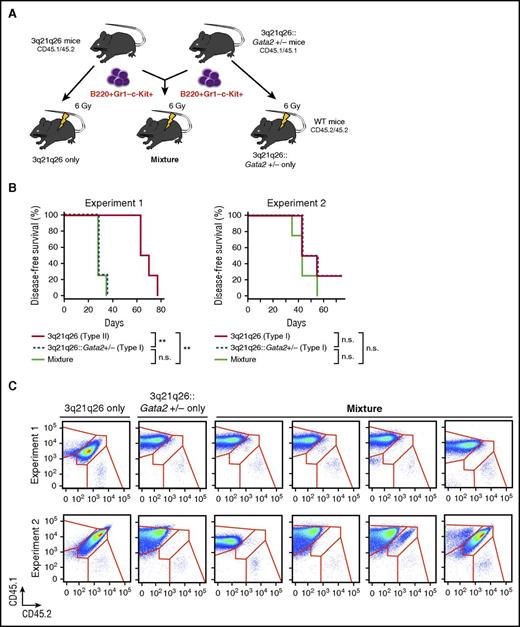

Selective expansion of 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemia cells in transplanted mice

To probe the mechanism underlying the acceleration of leukemogenesis caused by inactivation of a Gata2 allele, we compared the leukemia-initiating ability of B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice with that of the 3q21q26 mice. To this end, we adopted the strategy outlined in Figure 5A. We transplanted 5 × 104 B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from CD45.1/CD45.2 leukemic 3q21q26 mice and CD45.1 cells from 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice or a mixture containing 2.5 × 104 B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells of each genotype into sublethally irradiated WT CD45.2 animals.

3q21q26::Gata2+/−leukemia cells expand advantageously compared with the 3q21q26 leukemia cells. (A) Schema for the transplantation analysis. Either 5 × 104 B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from leukemic 3q21q26 mice (CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygotes), and/or from 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (CD45.1 homozygous) mice, or a mixture of 2.5 × 104 cells each from those same populations were independently transplanted into 3 sets of sublethally irradiated CD45.2 WT mice. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice that received B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from leukemic 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice. In Experiment 1 (left panel), the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from leukemic 3q21q26 Type II mice (n = 4; median, 66.5 days), 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice Type I (n = 4; median, 28.0 days), and the mixture (n = 4; median, 28.0 days) were observed for the given days survived. In Experiment 2 (right panel), B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from leukemic 3q21q26 Type I mice (n = 4; median, 49.0 days), 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I mice (n = 4; median, 48.5 days), and the mixture (n = 4; median, 42.0 days) were observed for survival. (C) Flow cytometric patterns of CD45.1 and CD45.2 in the bone marrows of WT mice receiving B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from 3q21q26 or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice alone or from the mixture. **P < .01. n.s., not significant.

3q21q26::Gata2+/−leukemia cells expand advantageously compared with the 3q21q26 leukemia cells. (A) Schema for the transplantation analysis. Either 5 × 104 B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from leukemic 3q21q26 mice (CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygotes), and/or from 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (CD45.1 homozygous) mice, or a mixture of 2.5 × 104 cells each from those same populations were independently transplanted into 3 sets of sublethally irradiated CD45.2 WT mice. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice that received B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from leukemic 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice. In Experiment 1 (left panel), the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from leukemic 3q21q26 Type II mice (n = 4; median, 66.5 days), 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice Type I (n = 4; median, 28.0 days), and the mixture (n = 4; median, 28.0 days) were observed for the given days survived. In Experiment 2 (right panel), B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from leukemic 3q21q26 Type I mice (n = 4; median, 49.0 days), 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I mice (n = 4; median, 48.5 days), and the mixture (n = 4; median, 42.0 days) were observed for survival. (C) Flow cytometric patterns of CD45.1 and CD45.2 in the bone marrows of WT mice receiving B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from 3q21q26 or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice alone or from the mixture. **P < .01. n.s., not significant.

We first examined the 3q21q26 Type II and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I leukemic cells as donors (Experiment 1). The mice that received a mixture of 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells or the mice that received cells from only the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice developed leukemia with shorter latency than the mice that received B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells from the 3q21q26 mice (Figure 5B, left panel). We then analyzed expression profiles of CD45.1 and CD45.2 in leukemic recipient mice and found that a majority of the leukemic cells were homozygous for CD45.1 and were therefore derived from the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− donors in all 4 recipients (Figure 5C, upper panels).

We next performed a competitive transplantation experiment using the 3q21q26 Type I and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I leukemic B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells that exhibited comparable latencies when they were independently transplanted into WT mice (Experiment 2; Figure 5B, right panel). Consistent with our earlier results, the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells expanded advantageously in 3 of the 4 recipients (Figure 5C, lower panels), whereas 3q21q26 leukemic cells expanded more modestly in the mixed recipients. These results indicate that the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemia cells acquired a selective advantage for leukemia induction when compared with the 3q21q26 leukemia cells.

Gata2 haploinsufficiency affects hematopoietic gene expression

To examine the mechanisms underlying the leukemia enhancement elicited by Gata2 haploinsufficiency, we analyzed gene expression profiles in B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells of the 3q21q26 Type II and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I leukemic mice by RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). Gene set enrichment analyses using hallmark gene sets23 identified 6 gene sets (ie, oxidative phosphorylation, MYC targets, reactive oxygen species pathway, DNA repair, PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, and p53 pathway) as significantly enriched in genes upregulated in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice when compared with the 3q21q26 mice, reflecting high proliferation rates and stress responses (Figure 6A).

Gata2 haploinsufficiency affects gene expression related to energy production and stress responses. (A) Histograms from gene set enrichment analyses using hallmark gene sets.23 Six gene sets (oxidative phosphorylation, MYC targets v1, reactive oxygen species pathway, DNA repair, PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, and p53 pathway) were significantly enriched (nominal P value < .05 or false discovery rate [FDR] q value < 0.25) in genes upregulated in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice compared with the 3q21q26 mice. As genes related to oxidative phosphorylation, PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, and MYC targets are enriched in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice, we assume that 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells promote cell expansion supported by high-energy production based on productive oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, we surmise that the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells acquire defenses to reactive oxygen species (ROS) after DNA damage as a consequence of oxidative phosphorylation and proliferation, because genes related on the ROS, DNA repair, and p53 pathways are enriched. In contrast, there was no gene set that was significantly enriched in genes downregulated in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice. The normalized enrichment scores (NES), the nominal P values and the FDR q values are indicated. (B) A scatter plot comparing transcript levels of the 3q21q26 mice (x-axis) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (y-axis). Shown are 151 and 226 genes significantly upregulated or downregulated, respectively, in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− compared with the 3q21q26 leukemic mice. (C) Expression levels of the Gfi1b, Klf2, Pim1, and Evi5 mRNAs as fragments per kb of exon per million fragments read (FPKM). Bar graphs represent mean ± SD.

Gata2 haploinsufficiency affects gene expression related to energy production and stress responses. (A) Histograms from gene set enrichment analyses using hallmark gene sets.23 Six gene sets (oxidative phosphorylation, MYC targets v1, reactive oxygen species pathway, DNA repair, PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, and p53 pathway) were significantly enriched (nominal P value < .05 or false discovery rate [FDR] q value < 0.25) in genes upregulated in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice compared with the 3q21q26 mice. As genes related to oxidative phosphorylation, PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, and MYC targets are enriched in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice, we assume that 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells promote cell expansion supported by high-energy production based on productive oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, we surmise that the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells acquire defenses to reactive oxygen species (ROS) after DNA damage as a consequence of oxidative phosphorylation and proliferation, because genes related on the ROS, DNA repair, and p53 pathways are enriched. In contrast, there was no gene set that was significantly enriched in genes downregulated in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice. The normalized enrichment scores (NES), the nominal P values and the FDR q values are indicated. (B) A scatter plot comparing transcript levels of the 3q21q26 mice (x-axis) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (y-axis). Shown are 151 and 226 genes significantly upregulated or downregulated, respectively, in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− compared with the 3q21q26 leukemic mice. (C) Expression levels of the Gfi1b, Klf2, Pim1, and Evi5 mRNAs as fragments per kb of exon per million fragments read (FPKM). Bar graphs represent mean ± SD.

By RNA-seq, we found that the abundances of 151 and 226 genes were significantly upregulated or downregulated, respectively, in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− compared with the 3q21q26 leukemic mice (Figure 6B). To identify GATA2 target genes that could be responsible for or correlated with leukemic malignancy, we identified GATA-occupied binding sites within or near these genes by using the GATA2 chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing database from K562 cells24 (ENCODE; see supplemental Data). We then compared these with genes that were expressed significantly differently in the cells expressing GATA2 from 1 vs 2 alleles in our RNA-seq data. As a result, we found 98 and 110 GATA2-occupied genes in the upregulated and downregulated group of genes, respectively, in comparing data from 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice with that from 3q21q26 mice. We found tumor-promoting genes such as Pim125,26 and Evi527 in the upregulated group and tumor-suppression genes such as Gfi1b and Klf228 in the downregulated group in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (Figure 6C). It is interesting to note that Gfi1b is reportedly a direct target of GATA2 and is highly expressed in hematopoietic stem cells.29 In addition, Gfi1b deficiency has been shown to induce the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells.29,30 These results suggest that the reduction of Gfi1b may contribute, at least in part, to the expansion of leukemic cells. Thus, GATA2 expression level–derived changes in the hematopoietic gene expression network seem to contribute to a more robust leukemic malignancy caused by 3q21q26 translocation.

Discussion

Reciprocal chromosomal translocation and inversion affect gene expression related to the rearrangements at least at 2 genome sites. As for the 3q21q26 chromosomal rearrangement, EVI1 becomes misexpressed by recruiting the Gata2 distal hematopoietic enhancer G2DHE to close proximity,5,6 whereas Gata2 gene expression is decreased in HSPCs by 50% because of the loss of G2DHE from the locus.6 Here we demonstrate in a mouse model that the Gata2 heterozygous deletion induces early transformation and accelerates leukemia promotion of EVI1 misexpressing HSPCs. We defined a B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population as that which contains leukemia-initiating cells in 3q21q26 mice. Our results demonstrate that the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells differentiate into Gr1+ myeloid leukemia cells when GATA2 is highly expressed. In contrast, we also found that concomitant with the GATA2 heterozygous LOF and consequent reduction of GATA2 gene expression, myeloid differentiation is rather suppressed, and blast-like cell expansion is promoted. These results demonstrate that the chromosomal rearrangement between 3q21 and 3q26 provokes malignant leukemia as a consequence of both EVI1 misexpression induction and GATA2 haploinsufficiency. We show our present model in Figure 7.

The current model for the contribution of EVI1 misexpression and Gata2 haploinsufficiency to leukemogenesis. Although EVI1 misexpression promotes expansion of the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ leukemic progenitors, GATA2 abundance contributes to fate determination of the EVI1-expressing leukemic cells. The B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells that express high GATA2 exhibit a GMP-like phenotype and differentiate into Gr1+ myeloid leukemic cells (upper arrow). In contrast, when Gata2 expression levels in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population are diminished, because of either Gata2 heterozygous deletion or spontaneous (unknown) mutations, the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells fail to differentiate into the myeloid lineage and acquire B-lymphoid–primed (lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor [LMPP] to pre-pro B-like) characteristics (lower arrow). Furthermore, Gata2 reduction enhances expansion of the leukemic cells, which results in a more aggressive leukemia.

The current model for the contribution of EVI1 misexpression and Gata2 haploinsufficiency to leukemogenesis. Although EVI1 misexpression promotes expansion of the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ leukemic progenitors, GATA2 abundance contributes to fate determination of the EVI1-expressing leukemic cells. The B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells that express high GATA2 exhibit a GMP-like phenotype and differentiate into Gr1+ myeloid leukemic cells (upper arrow). In contrast, when Gata2 expression levels in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population are diminished, because of either Gata2 heterozygous deletion or spontaneous (unknown) mutations, the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells fail to differentiate into the myeloid lineage and acquire B-lymphoid–primed (lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor [LMPP] to pre-pro B-like) characteristics (lower arrow). Furthermore, Gata2 reduction enhances expansion of the leukemic cells, which results in a more aggressive leukemia.

In addition to 3q21 (GATA2), 3q26 (EVI1) is also known to link to other partners such as 12p13 and 21q22, in which ETV6 (TEL) and RUNX1 (AML1), respectively, become mislocated by chromosomal translocation.31,32 These translocations induce expression of ETV6-EVI1 and RUNX1-EVI1 fusion proteins, and the amino acid sequence derived from EVI1 protein occupies a majority in these fusion proteins, whereas the portions from ETV6 and RUNX1 occupy only a small part in the N-terminal end of the chimeric proteins.31,32 Therefore, EVI1 expression is known to be a predominant cause of these leukemias. Because both ETV6 and RUNX1 encode transcription factors that are expressed in HSPCs,33,34 we surmise that in both cases EVI1 is ectopically expressed in HSPCs driven by normal hematopoietic regulatory elements of the ETV6 and RUNX1 genes. In this regard, it should be noted that 5-year overall survival rates of patients with rearrangements between EVI1 and GATA2 (ie,, the 3q21q26 syndrome) are much lower than those with chimeric proteins elicited by rearrangements between EVI1 and other partner proteins.35 We surmise that the GATA2 haploinsufficiency accounts for, albeit only in part, the poor prognosis of leukemia associated with inv(3)(q21q26) and t(3;3)(q21;q26).

The chromosomal rearrangements between 3q21 and 3q26 are mainly observed in myeloid leukemia but not lymphoid leukemia.35 In this study, we observed that the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice have B-lymphocyte–primed characteristics. However, these cells do not express the differentiated B-cell marker CD19 or the B-cell master regulators EBF1 and PAX5. In addition, full V-D-J rearrangement of the IgH loci is not observed in the cells. These results suggest that the 3q21q26 leukemias retain early lymphoid characteristics but have not been clinically diagnosed as lymphoid leukemias. Consistent with this observation, previous mouse studies showed that early B-cell progenitors retain myeloid differentiation potential but commit to the B-cell lineage by repressing myeloid genes.36,37 Thus, an intriguing possibility is that GATA2 and EVI1 determine the fate of an immature myeloid B-cell bipotential progenitor.

To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence that GATA2 haploinsufficiency contributes to leukemia associated with 3q21 and 3q26 chromosomal rearrangements. Patients who have AML with 3q21 and 3q26 translocations or inversions have an extremely poor prognosis, and one of the reasons is their low rates of complete remission.35 Our results indicate that GATA2 upregulation induces myeloid differentiation in leukemic cells and delays progression. Therefore, we assume that activation of GATA2 in those leukemias may be an effective therapeutic approach for treatment. Further development of therapeutic strategies targeting not only EVI1 but also GATA2 and associated factors is awaited to treat these leukemias.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nozomi Hatanaka, Eriko Naganuma, and the Biomedical Research Core of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine for technical support.

This work was supported in part by KAKENHI 15H02507 (M.Y.) and 24790957 (M.S.) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Authorship

Contribution: S. Katayama and M.S. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; A.Y. and N.K.-L. performed the experiments; F.K. and A.O. organized RNA-sequencing analysis and performed bioinformatics analyses; and S. Kure, J.D.E., and M.Y. supervised the project and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Masayuki Yamamoto, Department of Medical Biochemistry, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-1 Seiryo-machi, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi 980-8575, Japan; e-mail: masiyamamoto@med.tohoku.ac.jp; and Mikiko Suzuki, Center for Radioisotope Sciences, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-1 Seiryo-machi, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi 980-8575, Japan; e-mail: suzukimikiko@med.tohoku.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

S. Katayama and M.S. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Gata2 haploinsufficiency promotes leukemogenesis of 3q21q26 mice. (A) Schema of mating strategy. The numbers (percentages) of pups at weaning that bear the 4 possible genotypes is depicted. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT (n = 22; median, not determined), Gata2+/− (n = 22; median, not determined), 3q21q26 (n = 19; median, 345 days), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (n = 15; median, 276 days) mice. (C) Representative smears of peripheral blood taken from leukemic 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice and age-matched healthy WT and Gata2+/− mice. (D) White blood cell, red blood cell, and platelet counts in the peripheral blood of WT (n = 13), Gata2+/− (n = 11), 3q21q26 (n = 15), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (n = 14) mice. (E) Average spleen weights (left) from WT (bar 1 [n = 13]), Gata2+/− (bar 2 [n = 11]), 3q21q26 (bar 3 [n = 15]), and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (bar 4 [n = 14]) mice. Representative spleens from WT, Gata2+/−, leukemic 3q21q26, and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice are shown in right panel. Scale bar, 1 cm. (F) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the liver and lung from WT, Gata2+/−, leukemic 3q21q26, and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice. Parameters of the box plot are defined within the Statistical analysis paragraph in “Methods.” *P < .05; **P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/7/10.1182_blood-2016-12-756767/4/m_blood756767f1.jpeg?Expires=1769092801&Signature=B53vasqVmEW-fxKC~CesVBaPv9Z1fqi0hfFQWmf-MMR3cVyreduyylkoP6VlcKecFBkFSKgFMiB79G0izhWjTCoi-EpiTz12AdWtzIPzPrqIOBfetHoAAwxL6BKshs1x3iFyX1P5NXOfN--nOsR0K1AukoOmxMGWz9K4n4AuWs7O8rd~EWZhPWKr81SHhA~06FsEE59PAOaNXarur6As5R3s740bNuUYniynJaH5rtkFNkXy68qvibgpFTx0A~-bBRKNmXoNE5JncVkploua0kZf4UsNaQddIcwH5ATM-oNVmBHyOY0K2-vWhzQwa66OWbv0qe1DGcGFL2eUiGVSDw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. The 3q21q26 and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemia cells exhibit 2 distinct differentiation patterns. (A) Percentages of B220+Gr1– cells vs Gr1+ cells (B220+Gr1+ cells plus B220–Gr1+ cells) in bone marrows of the leukemic 3q21q26 (left panel [n = 60]) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (right panel [n = 32]) mice. We classified the leukemias into 4 types; Type I, II, III, and Unclassified based on the percentages of B220+Gr1– cells and Gr1+ (ie, B220+Gr1+ and B220–Gr1+) cells. The yellow-shaded area in both graphs indicates a range in which more than 80.0% of the leukemic bone marrow cells are both B220+ and Gr1+. The numbers of mice categorized into each type and their percentages are shown below the graphs. (B) Representative flow cytometric profiles of the bone marrows from Type I, II, III, and Unclassified leukemic 3q21q26 mice. (C) Representative smears of peripheral blood taken from Type I, II, III, and Unclassified leukemic 3q21q26 mice. (D) Percentages of c-Kit-positive cells in the bone marrow of the 3q21q26 Type I (n = 16), II (n = 18), III (n = 20), and Unclassified (n = 6) leukemia mice and the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 12), II (n = 2), III (n = 5), and Unclassified (n = 10) leukemia mice. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT mice transplanted with 3q21q26 Type I (n = 20; median, 28.0 days), II (n = 31; median, 38.5 days), and III (n = 28; median, 69.0 days) or 3q21q26::Gata2+/− Type I (n = 36; median, 23.5 days) leukemic whole bone marrow cells (0.5 to 1 × 106 cells).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/7/10.1182_blood-2016-12-756767/4/m_blood756767f2.jpeg?Expires=1769092801&Signature=o0IbaRf9SQP7FQUnF~QQaiS0e2VFDS5o3aJ8cjhZBxBsZvuT1HXL3dOdX3PVgiaiqoI~UAELx--E7n1WSk1~DH6NTw~DSk-QOve-DzHMGJ53PO3c83grfErh3ztziIdlcNh0QIZ5xXStIjYRO21-f725-6TaQvWgeoTzqFLKdPHDlHjaaGyXy63N5EpIMd9nYE6VdrvtQoou5pg3NuBN9f6kQnt94jFrlBYi2W3W3jZznfOypKwohpsrk3YSoNliFXAv5KYNT6-VfoIB2N0Vultm1W2Mxg980KnowSm9Rs256gZFqg-VjGWpDsCS9LSipcXM2RAitzbHo1c8SHchpQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. B220+ Gr1– c-Kit+ cells contain leukemia-initiating cells. (A) Representative flow cytometric profiles of c-Kit in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions of leukemic 3q21q26 (left) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− (right) mouse bone marrows. Note that the B220+Gr1– fraction is predominant in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice in right panel. (B) Percentages of c-Kit+ cells in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions in the bone marrow of the leukemic 3q21q26 mice (n = 35) and the B220+Gr1– fraction in the leukemic 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (n = 15). Parameters for the box plots are defined in the Statistical analysis paragraph of “Methods.” (C) Wright-Giemsa staining of leukemic cells in the B220+Gr1–, B220+Gr1+, and B220–Gr1+ fractions from the leukemic 3q21q26 and B220+Gr1– fraction from the leukemic 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (c-Kit+ [top line] and c-Kit− [bottom line]). (D) Colony-forming ability of B220+Gr1–c-Kit+, B220+Gr1+c-Kit+, B220–Gr1+c-Kit+, B220+Gr1–c-Kit–, B220+Gr1+c-Kit– and B220–Gr1+c-Kit– populations from the leukemic 3q21q26 mice (n = 6). Representative colony morphologies from the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+, B220+Gr1+c-Kit+, and B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ populations are shown in the right panels. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice receiving B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ (n = 16; median, 56 days), B220+Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 8; median, not determined), and B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 6; median, not determined) cells. (F) Representative flow cytometric patterns of leukemic cells in donor mice and donor-derived (CD45.1 homozygous or CD45.1/CD45.2 heterozygous) leukemic cells in recipient mice receiving B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells. (G) Relative expression levels of human EVI1 messenger RNA (mRNA) (left panel), total (human + mouse) EVI1 mRNA (middle panel), and mouse endogenous Gata2 mRNA (right panel) in B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ (n = 6), B220+Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 5), B220–Gr1+c-Kit+ (n = 4), B220+Gr1–c-Kit– (n = 4), B220+Gr1+c-Kit– (n = 3), and B220–Gr1+c-Kit– (n = 3) populations. Bar graphs represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). *, P < .05; **, P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/7/10.1182_blood-2016-12-756767/4/m_blood756767f3.jpeg?Expires=1769092801&Signature=MwQx-CaIWVsLO1DrIRggGwYzDI1OzzF48z4Ty2Sms6SnsEeprw3TMzRBiQ~nEcCs-cuK4KuX7xiNuk5pMI1xd2ES~9UaMwznRNvyDQB3NygxHmn2ugwwo~iLdK55euP6RlHV9M0QHb~lXy2GB46RZgabUmhoLt0tQ8E0c~xa58ea7Uew0iegHVcBOHbU1mQbi19qLgcMtYITewnF51aAizTpXnGblPNsE0e5D5r-5Saxh~gw5IVHozBroG-~fXD66reumxiXNFfZj3iHVOJUovQjYl5Im2orUt5sP~pbCNYf7kwQvbMoelask8Az71ZpBCO3urMO-2rz4azC52aXug__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Gata2 haploinsufficiency affects gene expression related to energy production and stress responses. (A) Histograms from gene set enrichment analyses using hallmark gene sets.23 Six gene sets (oxidative phosphorylation, MYC targets v1, reactive oxygen species pathway, DNA repair, PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, and p53 pathway) were significantly enriched (nominal P value < .05 or false discovery rate [FDR] q value < 0.25) in genes upregulated in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice compared with the 3q21q26 mice. As genes related to oxidative phosphorylation, PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, and MYC targets are enriched in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice, we assume that 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells promote cell expansion supported by high-energy production based on productive oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, we surmise that the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− leukemic cells acquire defenses to reactive oxygen species (ROS) after DNA damage as a consequence of oxidative phosphorylation and proliferation, because genes related on the ROS, DNA repair, and p53 pathways are enriched. In contrast, there was no gene set that was significantly enriched in genes downregulated in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice. The normalized enrichment scores (NES), the nominal P values and the FDR q values are indicated. (B) A scatter plot comparing transcript levels of the 3q21q26 mice (x-axis) and 3q21q26::Gata2+/− mice (y-axis). Shown are 151 and 226 genes significantly upregulated or downregulated, respectively, in the 3q21q26::Gata2+/− compared with the 3q21q26 leukemic mice. (C) Expression levels of the Gfi1b, Klf2, Pim1, and Evi5 mRNAs as fragments per kb of exon per million fragments read (FPKM). Bar graphs represent mean ± SD.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/7/10.1182_blood-2016-12-756767/4/m_blood756767f6.jpeg?Expires=1769092801&Signature=lwSDHFfNkq7LTu95t38lWd1SSYn~4qZK0sU5Fbh-dzMAhUovtZX7yDmlG9aswYqJSOX5dTFXy5rPg4Fn1TnkUF4xrIdryq9nxl-PpzNoM2QPAmfHmTVpWbYX6CeCvGoRvUhQKHEbrNYC5FLj6cGtcdatTmYlDU722Tj-o9S0I~4dIqf8Mg1STeEOyQPNcxOFs86XdViRlHZNMj3dG2Fm6x4kPNB0bX1sRXiZOgt-Jc6RF7x8ApvkwNtriuGfiVVw7GRYrbVj9wLfj8ZinAnALm~-BujJzU0j4OS2x~WmOYDrVW746oRivSxXd6cer7iMtZ0oVC06zHFChdYOhu9-GA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. The current model for the contribution of EVI1 misexpression and Gata2 haploinsufficiency to leukemogenesis. Although EVI1 misexpression promotes expansion of the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ leukemic progenitors, GATA2 abundance contributes to fate determination of the EVI1-expressing leukemic cells. The B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells that express high GATA2 exhibit a GMP-like phenotype and differentiate into Gr1+ myeloid leukemic cells (upper arrow). In contrast, when Gata2 expression levels in the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ population are diminished, because of either Gata2 heterozygous deletion or spontaneous (unknown) mutations, the B220+Gr1–c-Kit+ cells fail to differentiate into the myeloid lineage and acquire B-lymphoid–primed (lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor [LMPP] to pre-pro B-like) characteristics (lower arrow). Furthermore, Gata2 reduction enhances expansion of the leukemic cells, which results in a more aggressive leukemia.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/7/10.1182_blood-2016-12-756767/4/m_blood756767f7.jpeg?Expires=1769092801&Signature=xQ3R6l8-n-Cea~svTMfnhkHaBS3wp9UFYlu4HmKehoBgjRlKTEmrc0VED2puCnzqw9vZkvriZ-xYakn3cxKWBBS-yrAhiuzLqG2kG5MtsaZ7RX4FXt7gLV9JK7N2~mWQ4V1dNp1uDl4TcGR-2Bm30FuxEGMTSoqJQppNZCjsxl5KiptyPt3YwcCK7VTRFb2VD~aDBvf3L4OikQE8O0CRvr~m5f558FAxiFGS02bJAcfHkp4AE8Q4dKJcpiq~GGcO4jGkvC-MYgj6rsYQmFctgYDZgO6GTvPCuZuKEzJPeCAjNozSWengjuF3XDgLk~Xb3Hx625SL2GiloJwuGUCadA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal