The superior efficacy of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in the management of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), including a significant reduction in cardiovascular death, has led to a search for potential mechanisms for this superiority, such as in this issue of Blood in the work of Aungraheeta et al. They describe a novel property of ticagrelor in its interaction with the P2Y12 receptor as well as confirming adenosine-mediated effects through inhibition of cellular adenosine uptake via equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1).1

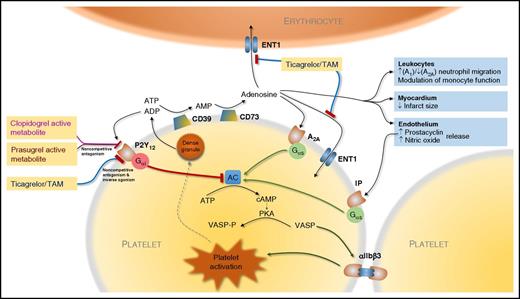

Actions of ticagrelor, prasugrel, and clopidogrel mediated by P2Y12 and adenosine. Ticagrelor acts directly and via an active metabolite (TAM) with both noncompetitive antagonism of activation by ADP and inverse agonism at P2Y12. In addition, ticagrelor and TAM weakly inhibit ENT1 leading to increased extracellular adenosine that acts via adenosine receptors such as A1 and A2A receptors, the latter mediating platelet inhibition. The prodrugs prasugrel and clopidogrel produce active metabolites that bind irreversibly to P2Y12 with noncompetitive antagonism of ADP binding. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and ADP released from platelet dense granules are degraded to adenosine via platelet surface CD39 (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1) and CD73 (5′-nucleotidase). Activation of P2Y12 by ADP leads to activation of the Gαi and inhibition of adenylate cyclase (AC) with consequent fall in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which leads to reduced activity of protein kinase A (PKA) and consequent phosphorylation of VASP (VASP-P). Conversely, activation of A2A receptors by adenosine and prostacyclin receptor (IP) by endothelium-derived prostacyclin leads to activation of the stimulatory G protein α subunit (Gαs) and activation of AC. The balance of platelet activation and its inhibition regulated via AC and other intracellular signaling pathways modulates the affinity of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex (αIIbβ3) for fibrinogen and consequent platelet-platelet aggregation.

Actions of ticagrelor, prasugrel, and clopidogrel mediated by P2Y12 and adenosine. Ticagrelor acts directly and via an active metabolite (TAM) with both noncompetitive antagonism of activation by ADP and inverse agonism at P2Y12. In addition, ticagrelor and TAM weakly inhibit ENT1 leading to increased extracellular adenosine that acts via adenosine receptors such as A1 and A2A receptors, the latter mediating platelet inhibition. The prodrugs prasugrel and clopidogrel produce active metabolites that bind irreversibly to P2Y12 with noncompetitive antagonism of ADP binding. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and ADP released from platelet dense granules are degraded to adenosine via platelet surface CD39 (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1) and CD73 (5′-nucleotidase). Activation of P2Y12 by ADP leads to activation of the Gαi and inhibition of adenylate cyclase (AC) with consequent fall in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which leads to reduced activity of protein kinase A (PKA) and consequent phosphorylation of VASP (VASP-P). Conversely, activation of A2A receptors by adenosine and prostacyclin receptor (IP) by endothelium-derived prostacyclin leads to activation of the stimulatory G protein α subunit (Gαs) and activation of AC. The balance of platelet activation and its inhibition regulated via AC and other intracellular signaling pathways modulates the affinity of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex (αIIbβ3) for fibrinogen and consequent platelet-platelet aggregation.

The platelet adenosine diphosphate (ADP) P2Y12 receptor plays a central role in the amplification of the responses to a number of potent proaggregatory agonists such as collagen and thrombin, including through linkage to the inhibitory G protein α subunit (Gαi), which leads to reduced phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) and subsequent activation of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors, which represents the final pathway of platelet aggregation (see figure).2 Platelet P2Y12 therefore offers a powerful and specific target for antiplatelet therapy. There are currently 3 widely used oral P2Y12 inhibitors: the irreversibly binding thienopyridine prodrugs clopidogrel and prasugrel and the reversibly binding cyclopentyl-triazolopyrimidine directly active ticagrelor.

Clinical use of ticagrelor in ACS is supported by a large randomized controlled trial of the drug vs clopidogrel, the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) study, as well as further evidence that this benefit persists in the longer term in those at high ischemic risk.3,4 The superiority of ticagrelor over clopidogrel seen in PLATO, particularly with regard to cardiovascular (hazard ratio [HR], 0.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.69-0.91; P = .001) and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.69-0.89; P < .001) led to further exploration of its mechanisms of action.

As well as inhibiting platelet P2Y12, ticagrelor was found to possess the unexpected property of weak inhibition of the uptake of adenosine by erythrocytes via ENT1,5 which may lead to increased tissue availability of adenosine and increased detectable levels in the plasma.6 This effect has been linked to various hypothesized pleiotropic effects, which remain to be fully explored, including an increase in the release of antiplatelet factors such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide from the endothelium, limitation of myocardial infarct size in an animal model and modulation of innate immunity (see figure),7-9 and notable side effects such as dyspnea, increased uric acid levels, and ventricular pauses.3

The work by Aungraheeta et al presented in this issue provides 2 new, important insights into the unique mechanisms of ticagrelor’s action when compared with other P2Y12 inhibitors, explored using elegant in vitro studies. First, they confirm that, as well as inhibiting ENT1 on erythrocytes, ticagrelor antagonizes the same transporter found on platelets (see figure). This is significant as not only may this mechanism contribute to the increased circulating and tissue levels of adenosine with its putative effects on the endothelium and myocardium, but it also raises the possibility of local potentiation of adenosine availability close to the platelet cell membrane, particularly given the probable ability of platelets to break down ADP and ATP to adenosine through activity of CD38 and CD73. Local levels may hypothetically therefore exceed those measured in the plasma as a whole.

It should be noted that the effects of adenosine appear to be highly concentration-dependent with sometimes dichotomous cellular responses: for example, activation of neutrophil A1 receptors by adenosine present in nanomolar concentration inhibits adenylate cyclase via coupling to Gαi, promoting chemotaxis and phagocytosis, whereas at higher (micromolar) levels adenosine neutralizes or reverses this effect via activation of the lower-affinity A2A receptor coupled to Gαs, exerting an anti-inflammatory action. Given that in states of inflammation platelet-leukocyte aggregates are formed, such local increases may influence adenosine-mediated effects on immunity, potentially contributing to the explanation for the post hoc observation in the PLATO study that ticagrelor therapy was associated with fewer deaths following pulmonary infections compared with clopidogrel therapy.4 Platelets themselves express high levels of A2A receptors, and their activation by adenosine, as confirmed in this study, contributes to platelet inhibition by ticagrelor in addition to the direct P2Y12-mediated effect.

Second, they show that, in addition to acting as a potent antagonist of ADP at the P2Y12 receptor, ticagrelor acts as an inverse agonist in vitro. In other words, it not only blocks the action of ADP on the receptor, but is also able to reduce the basal level of receptor signaling in the unstimulated state, an effect that was not seen with prasugrel active metabolite or the experimental ATP analog AR-C66096. As well as the effects mediated through increased availability of adenosine, additional effects appear to be because of direct interactions between ticagrelor and P2Y12 in a manner that is noncompetitive with ADP. Considering the prominent role of P2Y12 signaling in amplification of platelet activation induced by multiple stimuli and the exposure of platelets to highly thrombogenic conditions during an ACS event, reducing the constitutive activity of P2Y12 receptor signaling may be beneficial over and above the effect of merely blocking ADP’s action. Further work is required to determine whether this contributes to the observations from ex vivo platelet function testing in patients with ACS that ticagrelor maintenance therapy provides more potent P2Y12 inhibition than prasugrel or clopidogrel maintenance therapy or whether this is simply a matter of differences in extent of receptor blockade.10

Although the authors acknowledge that these mechanisms remain to be confirmed in patients receiving antiplatelet therapy and their significance pertaining to the overall clinical effect of ticagrelor is still undetermined, their findings represent further steps in the understanding of how ticagrelor potently and consistently inhibits platelet activation, improving outcomes in ACS, and offer more insight into potential adenosine-related pleiotropic effects, thus supporting future exploration of ticagrelor’s effects in atherothrombosis and inflammation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: W.A.E.P. reports an honorarium from Medscape Cardiology. R.F.S. reports institutional research grants/support from AstraZeneca and PlaqueTec; consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Aspen, Avacta, ThermoFisher Scientific, PlaqueTec, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, and the Medicines Company; and honoraria from AstraZeneca.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal