Key Points

HNPs inhibit proteolytic cleavage of VWF by ADAMTS13 by physically blocking VWF-ADAMTS13 interactions.

Plasma levels of HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 are markedly increased in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP.

Abstract

Infection or inflammation may precede and trigger formation of microvascular thrombosis in patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). However, the mechanism underlying this clinical observation is not fully understood. Here, we show that human neutrophil peptides (HNPs) released from activated and degranulated neutrophils inhibit proteolytic cleavage of von Willebrand factor (VWF) by ADAMTS13 in a concentration-dependent manner. Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations of native HNPs toward ADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis of peptidyl VWF73 and multimeric VWF are 3.5 μM and 45 μM, respectively. Inhibitory activity of HNPs depends on the RRY motif that is shared by the spacer domain of ADAMTS13. Native HNPs bind to VWF73 (KD = 0.72 μM), soluble VWF (KD = 0.58 μM), and ultra-large VWF on endothelial cells. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) demonstrates markedly increased plasma HNPs1-3 in most patients with acquired autoimmune TTP at presentation (median, ∼170 ng/mL; range, 58-3570; n = 19) compared with healthy controls (median, ∼23 ng/mL; range, 6-44; n = 18) (P < .0001). Liquid chromatography plus tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) reveals statistically significant increases of HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 in patient samples (all P values <.001). There is a good correlation between measurement of HNPs1-3 by ELISA and by LC-MS/MS (Spearman ρ = 0.7932, P < .0001). Together, these results demonstrate that HNPs1-3 may be potent inhibitors of ADAMTS13 activity, likely by binding to the central A2 domain of VWF and physically blocking ADAMTS13 binding. Our findings may provide a novel link between inflammation/infection and the onset of microvascular thrombosis in acquired TTP and potentially other immune thrombotic disorders.

Introduction

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), characterized by disseminated platelet-rich microvascular thrombosis, is primarily caused by severe deficiency of plasma metalloprotease ADAMTS13 activity.1 Inherited mutations of ADAMTS13 and de novo production of autoantibodies against ADAMTS13 result in severe deficiency of plasma ADAMTS13 activity in hereditary1,2 and acquired (idiopathic) TTP,1,3 respectively. The age of onset in patients with hereditary TTP directly correlates with plasma ADAMTS13 activity; the lower plasma ADAMTS13 activity, the earlier the clinical onset.4 Similarly, low levels of plasma ADAMTS13 activity in the presence of inhibitors, but not the anti-ADAMTS13 immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels themselves, are associated with the high incidence relapse and mortality rates in patients with acquired TTP.5,6 These results suggest that ADAMTS13 inhibitors may not be restricted to anti-ADAMTS13 IgG antibodies. For instance, ADAMTS13-specific IgA or IgM antibodies were detected in a small subset of patients with acquired TTP5 ; the affinity of anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies for their epitopes and the frequency of the targeted epitopes may vary from 1 patient to another; in addition, free hemoglobin7,8 and unconjugated bilirubin9 may inhibit plasma ADAMTS13 activity. However, the mechanisms that regulate plasma ADAMTS13 activity under normal and pathological conditions are not fully understood.

It is often noted that respiratory, gastrointestinal, and central line infections precede an acute episode of TTP,10-12 suggesting a potential link between infection/inflammation and microvascular thrombosis, the hallmark of pathological changes in TTP. During acute infections or systemic inflammation, human neutrophil peptides (HNPs), most abundantly HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 (also known as α-defensins), are released from activated neutrophils.13 These cationic and hydrophobic ∼29 to 30 amino acid polypeptides contribute to the innate immune response by binding and forming pores within the membranes of bacteria, viruses, and fungi leading to microbial death.13 Plasma concentrations of HNPs in healthy individuals are in the nanomolar range (or on average, ∼0.12 μg/mL), but the levels increase to the 100-μM range in patients with sepsis, bacterial meningitis,14 and systemic lupus erythematosus.15

In addition to their role in innate immunity, HNPs affect host cells in proximity to the sites of inflammation. HNPs activate platelets by enhancing the interactions between platelets and fibrinogen or thrombospondin-1 leading to aggregation, secretion of granule contents, shedding of soluble CD40L, and the expression of platelet surface procoagulant activity.16 In addition, HNPs may inhibit fibrinolysis by modulating the binding of tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen to fibrin and endothelial cells.17 The resultant localized microvascular thrombosis may be an integral component in host defense, but might also lead to infection/inflammation-associated microvascular thrombosis in settings where plasma ADAMTS13 levels are extremely low as in the cases of TTP.

Here, we demonstrate for the first time that HNPs inhibit the proteolytic cleavage of peptidyl VWF73 and multimeric von Willebrand factor (VWF) by ADAMTS13 in a concentration-dependent manner. This inhibitory effect appears to be mediated by tight binding between HNPs and the VWF-A2 domain, which presumably competes for binding of ADAMTS13 to VWF and renders it resistant to proteolysis. Plasma levels of HNPs1-3 or HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 are all markedly increased in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP who have severe deficiency of plasma ADAMTS13 activity. Together, our findings demonstrate a novel biological function of HNPs1-3, and suggest a potential link between inflammation, neutrophil activation, and microvascular thrombosis in TTP and possibly other inflammation-associated thrombotic disorders.

Methods

Materials

The institutional review boards of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved all studies involving human subjects and human materials. Acquired autoimmune TTP (n = 19) was defined in adult patients by the presence of marked thrombocytopenia (usually <50 000/μL), microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, organ dysfunction, severe deficiency of plasma ADAMTS13 activity (<10% of normal) with detectable inhibitors, and a negative direct antiglobulin test. Patients with overt sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pregnancy, cancer, and hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation at the presentation were excluded from the study. Healthy controls (n = 18) were recruited from regular blood donors. After informed consent was obtained, 5 mL of whole blood was collected by peripheral venous puncture (healthy donors) at time of blood donation or via central catheter (TTP patients) prior to the initiation of the first therapeutic plasma exchange. The blood was anticoagulated with 0.32% sodium citrate (final concentration) and platelet-poor plasma was prepared by centrifugation at 1500g for 10 minutes and stored in aliquots at −80°C until assay.

HNPs were purified to homogeneity from sputum collected from patients with cystic fibrosis using methods described previously.18,19

Synthetic peptides of wild type (WT) HNP1 (ACYCRIPACIAGERRYGTCIYQGRLWAFCC) and 2 analogs: HNP1-RRY/AAA (ACYCRIPACIAGEAAAGTCIYQGRLWAFCC) and HNP1-delRRY (ACYCRIPACIAGE- - -GTCIYQGRLWAFCC) were chemically synthesized at Peptide 2.0 (Chantilly, VA). The RRY motif that is homologous to that found in the spacer domain of ADAMTS13 is underlined.

Recombinant human ADAMTS13 (rADAMTS13) was expressed and purified to homogeneity from the conditioned medium of stably transfected human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells as described.20-22 Multimeric human VWF was purified from cryoprecipitate of normal human plasma using ion exchange and gel filtration chromatography as described.23

Fluorescein-5-malaimide–labeled VWF73 peptide (rF-VWF73)24,25 and glutathione S-transferase (GST)-VWF73-H26 were prepared according the protocols described previously. Fluorescein-5-maleimide or Alexa Fluor 488-5-maleimide, Alexa Fluor 594-5-maleimide, mass spectrometry–grade acetonitrile, formic acid, and water were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was purchased from Burdick & Jackson (Morristown, NJ). Alexa 488–conjugated HNPs were prepared according the manufacturer’s recommendation (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

ADAMTS13 activity assays

Surface plasmon resonance

The binding kinetics of HNPs to GST-VWF73-H and multimeric VWF was measured by surface plasmon resonance technology using the BIAcore3000 optical biosensor instrument (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden) as described.22 Briefly, a CM5-sensor chip (Biacore AB) was activated and immobilized with nothing (blank), with purified plasma VWF, or with recombinant GST-VWF73-H. Unbound amine groups were blocked with 1 mol/L ethanolamine at pH 8.5. After equilibration with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, 0.005% Tween 20, HNPs (0.02-10 μmol/L) were injected at 30 μL per minute. Specific binding of HNPs to GST-VWF73-H and VWF was determined by global fitting the sensograms using a simple 1:1 model after background subtraction.

Binding of HNPs to soluble VWF multimers

Purified HNPs (0.2∼2.0 µg) were incubated with plasma VWF (10 µg) in a total volume of 50 µL in the presence of 20 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 for 30 minutes. The reaction was terminated by addition of 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-sample buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 5% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.5% bromophenol blue) without heat denaturation. Binding of HNPs to purified VWF was measured using monoclonal anti-HNP1-3 (1:1000; Hycult Biotech Inc, Plymouth Meeting, PA), followed by Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:5000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) after electrophoresis on 1% SDS-agarose gel. To visualize VWF multimers, the same blot was subsequently incubated with rabbit anti-human VWF IgG (1:2000; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), followed by Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The fluorescent signals were obtained by scanning in an Odyssey CLx infrared imaging system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Binding of HNPs to ultra-large VWF on cultured endothelial cells under flow

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were grown to near confluence on a flow chamber slide (Ibidi-Integrated BioDiagnostics, Martinsried, Germany) coated with gelatin. The cells were washed and 100 μM histamine was added under flow (10 dyne/cm2) for 5 minutes. Alexa 488–labeled HNPs (10 µg/mL) were perfused through the channel for an additional 20 minutes. Alexa 488–labeled nonimmune IgG (green) was used as a control. After the cells were washed with PBS, they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100. The VWF “strings” along the endothelial surface were visualized under a Nikon fluorescent microscope after incubation with Alexa 594–labeled anti-VWF IgG (10 µg/mL) (red).

Enzyme-linked immunoassay

Total plasma levels of HNPs1-3 were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (Hycult Biotech Inc). Briefly, standards (at various dilutions) or plasma samples (1:100-1:2000) were added to a microtiter plate precoated with a monoclonal anti-human antibody that recognizes HNPs1-3. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 60 minutes. After 3 washes, a biotinylated monoclonal antibody that recognizes HNPs1-3 at a different epitope was added to the wells and incubated at 25°C for 60 minutes, followed by incubation with streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate and 3, 3′, 5, 5′ tetramethylbenzidine-hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reaction was stopped by addition of 1 N HCl and the absorbance in each well was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm. Concentrations of normal human plasma and patient plasma were determined from the calibration curve and expressed as nanograms per milliliter.

Liquid chromatography plus tandem mass spectrometry assay

Concentrations of total HNPs in 0.1% acetic acid were estimated by absorption spectroscopy. Calibration curves for HNP1 and HNP2 peptides (0, 5, 10, 20, 39, 78, 156, 313, 625, 1250, 2500, and 5000 ng/mL) were prepared by serial dilution in fetal bovine serum, which lacks human HNPs. HNPs in patient plasma or in fetal bovine serum were extracted by precipitating the proteins with 1% TFA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at room temperature. The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and the solvent was evaporated in a speed vacuum concentrator. The dried sample was reconstituted in 150 µL of 0.1% TFA, mixed vigorously for 3 minutes, and transferred to 0.3-mL autosampler tubes (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA), queued in an autosampler maintained at 8°C and injected within 12 hours. One microliter of extracted HNPs was ejected from the autosampler vials and washed in the trap column for 2 minutes after injection with 3% acetonitrile, followed by perfusion through a linear gradient from 3% to 90% acetonitrile in 15 minutes with solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The system was held at 90% solvent B for 2 minutes before returning the system to the initial condition of 3% solvent B. The total run time was 20 minutes. HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 were monitored by quasi-multiple reaction monitoring in the positive ion mode using a nanoAcquity nano flow HPLC system coupled to a Xevo TQ-S triple quadrapole mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation). The relative abundance of HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 in TTP patients was determined by comparison with the mean value of each HNP in normal human plasma, which was defined as 1 arbitrary unit (AU).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software (La Jolla, CA). The results are expressed as scatter plots showing the medians and ranges as indicated in the table and in each figure. Statistical significance was determined using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test for comparison between 2 groups (unpaired and 2-tailed) and the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ) for comparison between ELISA and liquid chromatography plus tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). P values <.05 and .01 were considered to be statistically significant and highly significant, respectively.

Results

HNPs inhibit proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 and multimeric VWF by ADAMTS13

To investigate the effect of HNPs on VWF proteolysis by ADAMTS13, we first purified native HNPs, plasma VWF, and rADAMTS13 as described in “Methods.” The rADAMTS13 protein migrated as a single band at the molecular weight of ∼195 kDa on a 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Figure 1A, lane 1). Purified native HNPs ran at ∼6 kDa on the same gel, suggesting the formation of dimers, similar to what has been previously described for HNP329 (Figure 1A, lane 2). Tandem mass spectrometric (MS/MS) analysis showed that our purified HNP preparation contained only HNP1 (m/z ratios of 689.1116, 689.3113, and 689.5112) and HNP2 (m/z ratios of 674.9053, 675.1050, and 675.3050) (Figure 1B) at an equal molar concentration. HNP3 and HNP4 were not detected in the preparations.

Characterization of purified rADAMTS13 and native HNPs. (A) Fifteen percent SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis demonstrates the purity of rADAMTS13 (2 µg per lane; lane 1) and purified native HNPs (2.0 µg per lane; lane 2) under denaturing but nonreducing conditions. (B) Mass spectrometric analysis demonstrates the relative abundance of HNP1 (m/z, 689.3113) and HNP2 (m/z, 675.3050) in the preparations. No peaks for HNP3 and HNP4 were seen. M, prestained molecular marker.

Characterization of purified rADAMTS13 and native HNPs. (A) Fifteen percent SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis demonstrates the purity of rADAMTS13 (2 µg per lane; lane 1) and purified native HNPs (2.0 µg per lane; lane 2) under denaturing but nonreducing conditions. (B) Mass spectrometric analysis demonstrates the relative abundance of HNP1 (m/z, 689.3113) and HNP2 (m/z, 675.3050) in the preparations. No peaks for HNP3 and HNP4 were seen. M, prestained molecular marker.

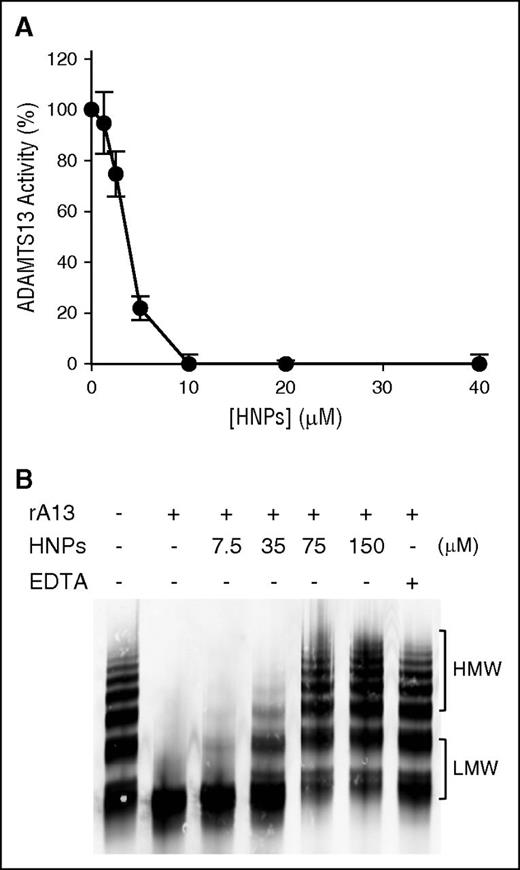

When purified HNPs were added to reactions containing either purified rADAMTS13 (10 nM) and rF-VWF73 (2 μM) or multimeric VWF (25 μg/mL), proteolytic cleavage of both rF-VWF73 (Figure 2A) and multimeric VWF (Figure 2B) was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner, with half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of ∼3.5 μM and ∼45 μM, respectively. As a positive control, EDTA (10 mM) added to the same reaction caused complete inhibition of rADAMTS13-mediated cleavage of VWF (Figure 2B lane 7). Moreover, HNPs added to plasma or whole blood also inhibited its ADAMTS13 activity, assessed by the cleavage of rF-VWF73, in a concentration-dependent manner (not shown). These results indicate that purified native HNPs are potent inhibitors of recombinant and plasma ADAMTS13 activity.

Purified native HPNs inhibit proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 and multimeric VWF by ADAMTS13. (A) Purified native HNPs (0-40 nM) were incubated with rF-VWF73 (2 µM) in the presence of rADAMTS13 (10 nM) and proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 was determined by the rate of fluorescence generation per minute. Relative residual activity was plotted against concentrations of HNPs (means ± SEM, n = 3). (B) Purified native HNPs (0-150 µM) were incubated with plasma-derived multimeric VWF (25 µg/mL) in the presence of rADAMTS13 (10 nM) for 4 hours on a dialysis membrane floating on top of 1.5 M urea, 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. In the last lane, EDTA (10 mM) was included as a control for complete inhibition of ADAMTS13 activity. The residual VWF was determined by 1% agarose electrophoresis, followed by western blotting with rabbit anti-VWF IgG. The results are representatives of 3 experiments. HMW, high molecular weight of VWF multimers; LMW, low molecular weight of VWF multimers; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Purified native HPNs inhibit proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 and multimeric VWF by ADAMTS13. (A) Purified native HNPs (0-40 nM) were incubated with rF-VWF73 (2 µM) in the presence of rADAMTS13 (10 nM) and proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 was determined by the rate of fluorescence generation per minute. Relative residual activity was plotted against concentrations of HNPs (means ± SEM, n = 3). (B) Purified native HNPs (0-150 µM) were incubated with plasma-derived multimeric VWF (25 µg/mL) in the presence of rADAMTS13 (10 nM) for 4 hours on a dialysis membrane floating on top of 1.5 M urea, 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. In the last lane, EDTA (10 mM) was included as a control for complete inhibition of ADAMTS13 activity. The residual VWF was determined by 1% agarose electrophoresis, followed by western blotting with rabbit anti-VWF IgG. The results are representatives of 3 experiments. HMW, high molecular weight of VWF multimers; LMW, low molecular weight of VWF multimers; SEM, standard error of the mean.

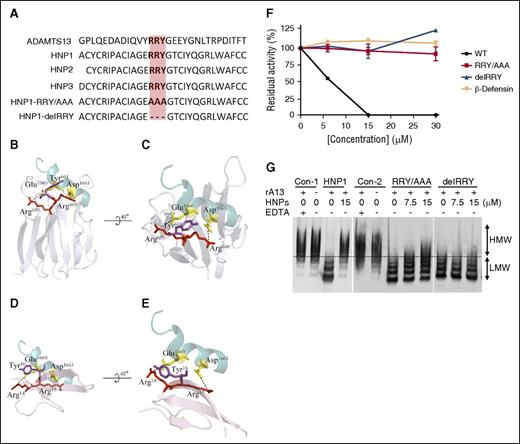

HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3, the most abundant peptides released from neutrophils following activation, are nearly identical in sequence except for the first amino acid residue with alanine and aspartic acid in HNP1 and HNP3, respectively, which is lacking in HNP2 (Figure 3A). HNP4, which is not detected in the granular contents of neutrophils, consists of 34 amino acid residues with similar disulfide bond patterning, but differing in sequence from HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3. HNP1-3 share a RRY motif, which is also present in the spacer domain of ADAMTS13 (Figure 3A) and may play an important role in substrate recognition, presumably by interacting with the C-terminal end of VWF73 as illustrated in the model (Figure 3B-C). We hypothesized that the RRY motif in HNP1-3 might interact directly with amino acid residues E1660 and D1663 in the VWF73 peptide (Figure 3D-E). To test this hypothesis, we prepared 3 synthetic HNP1 peptides (ie, WT HNP1, HNP1-RRY/AAA, and HNP1-delRRY). When added to the reactions containing rADAMTS13 (10 nM) and rF-VWF73 (2 μM) under the same conditions, WT HNP1, HNP2 (not shown), and HNP3 (not shown) inhibited proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 (Figure 3F) and multimeric VWF (Figure 3H) in a concentration-dependent manner. However, mutant HNP1-RRY/AAA or HNP1-delRRY did not inhibit rADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis of rF-VWF73 (Figure 3F) and multimeric VWF (Figure 3G). As an additional control, synthetic β-defensin, a small cationic/hydrophobic, highly disulfide-linked peptide, which lacks the RRY motif, did not inhibit proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 by rADAMTS13 (Figure 3F). Together, our results indicate that a specific interaction between HNPs and the central A2 domain of VWF may be necessary for the inhibition of VWF proteolysis by ADAMTS13.

Amino acid sequences of HNPs and the inhibitory activity of HNP1 and its mutants on proteolysis of rF-VWF73 and VWF by ADAMTS13. (A) Sequence alignment of a part of the ADAMTS13 spacer domain (G647-T669) with HNP1, HNP2, HNP3, and its mutants (HNP1-delRRY and HNP1-RRY/AAA). Highlighted in orange is the RRY motif. (B-C) The interactions between ADAMTS13-spacer and VWF-A2 fragment. Residues of Glu1660 and Asp1663 of VWF are shown as yellow sticks (PDB 3GXB). The spacer domain of ADAMTS13 is shown in silver (PDB 3GHM), with RRY shown as sticks. Arg659, Arg660, and Tyr661 appear to interact with Glu1660 and Asp1663 (dashed lines). (D-E) The interactions between HNPs1-3 and VWF73. Arg14, Arg15, and Tyr16 in HNP1-3 appear to interact with the same site (Glu1660 and Asp1663) on VWF73 where ADAMTS13 binds (dashed line). (F) The inhibitory activity of HNP1 (WT), HNP1-delRRY, HNP1-RRY/AAA, and β-defensin (0-30 µM) on proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 (2 µM) by rADAMTS13 (10 nM). (G) The inhibition of HNP1, HNP1-RRY/AAA, and HNP1-delRRY or buffer controls (Con-1 and Con-2) on proteolytic cleavage of multimeric VWF (10 µg/mL) by rADAMTS13 (10 nM). Plus (+) and minus (−) signs indicate the presence and absence of the component, respectively. HMW and LMW, separated by a dashed line, represent the high and molecular weights of VWF multimers, respectively.

Amino acid sequences of HNPs and the inhibitory activity of HNP1 and its mutants on proteolysis of rF-VWF73 and VWF by ADAMTS13. (A) Sequence alignment of a part of the ADAMTS13 spacer domain (G647-T669) with HNP1, HNP2, HNP3, and its mutants (HNP1-delRRY and HNP1-RRY/AAA). Highlighted in orange is the RRY motif. (B-C) The interactions between ADAMTS13-spacer and VWF-A2 fragment. Residues of Glu1660 and Asp1663 of VWF are shown as yellow sticks (PDB 3GXB). The spacer domain of ADAMTS13 is shown in silver (PDB 3GHM), with RRY shown as sticks. Arg659, Arg660, and Tyr661 appear to interact with Glu1660 and Asp1663 (dashed lines). (D-E) The interactions between HNPs1-3 and VWF73. Arg14, Arg15, and Tyr16 in HNP1-3 appear to interact with the same site (Glu1660 and Asp1663) on VWF73 where ADAMTS13 binds (dashed line). (F) The inhibitory activity of HNP1 (WT), HNP1-delRRY, HNP1-RRY/AAA, and β-defensin (0-30 µM) on proteolytic cleavage of rF-VWF73 (2 µM) by rADAMTS13 (10 nM). (G) The inhibition of HNP1, HNP1-RRY/AAA, and HNP1-delRRY or buffer controls (Con-1 and Con-2) on proteolytic cleavage of multimeric VWF (10 µg/mL) by rADAMTS13 (10 nM). Plus (+) and minus (−) signs indicate the presence and absence of the component, respectively. HMW and LMW, separated by a dashed line, represent the high and molecular weights of VWF multimers, respectively.

HNPs bind VWF73 and multimeric VWF

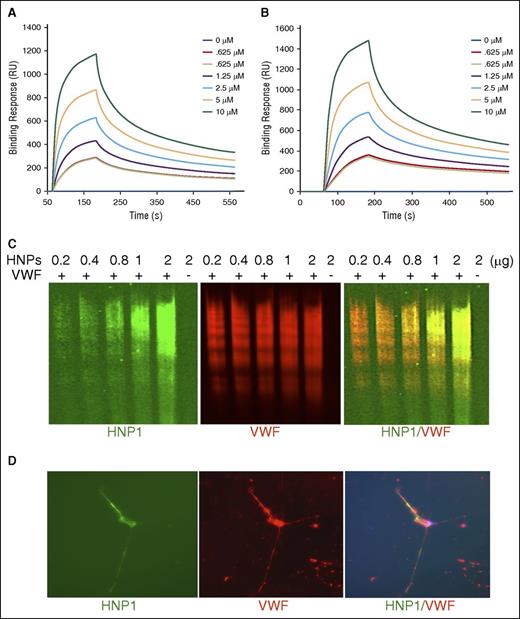

To understand the mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of HNPs on proteolysis of VWF by ADAMTS13, we analyzed the binding of HNPs to a minimal substrate GST-VWF73-H peptide, soluble multimeric VWF, and cell-bound ultra-large VWF strings on endothelial cells. First, when purified native HNPs (0-10 μM) were flowed over a CM5 sensor chip coated with purified recombinant GST-VWF73-H or plasma-derived multimeric VWF, HNPs bound to both GST-VWF73-H (Figure 4A) and multimeric VWF (Figure 4B) in a concentration-dependent manner with the calculated dissociation constants (KD) of 0.72 μM and 0.58 μM, respectively. Similar results were obtained with the binding of synthetic HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 toward GST-VWF73-H and multimeric VWF under the same conditions (data not shown). Second, purified native HNPs appeared to form SDS-stable complexes with multimeric VWF that migrated with the VWF ladders in a concentration-dependent manner demonstrated by western blotting with monoclonal anti-HNP1-3 IgG after agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 4C). The ladder pattern of HNP immunoblot suggests high-affinity binding of HNPs to VWF multimers. In the absence of such binding, HNPs would have run out of the gel because of their small sizes. Third, when perfused over histamine-stimulated endothelial cells grown on a microfluidic channel, Alexa 488 fluorescein-labeled native HNPs bound to newly released ultra-large VWF strings that were easily visualized under the fluorescence microscope (Figure 4D). Together, these results demonstrate that HNPs bind VWF and may physically block the binding of ADAMTS13 to the unfolded VWF-A2 domain, thereby inhibiting ADAMTS13-dependent proteolysis of VWF under the in vitro assay conditions.

Native HNPs bind to GST-VWF73-H, soluble VWF, and ultra-largeVWF on endothelial cells under flow. Purified native HNPs (0-6 µM) were flown on a CM5 surface covalently immobilized with purified recombinant GST-VWF73-H peptide (A) and multimeric VWF (B) under the flow rate of 20 µL per minute for 10 minutes. The bound HNPs are demonstrated by the increase in response units (RU) as a function of time. The representative curves of 3 independent experiments are shown. The dissociation constants KD (s) were determined by fitting the sensorgrams using the 1:1 Langmuir interaction model. (C) Purified native HNPs (0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.0, and 2.0 µg per lane) were incubated with purified plasma VWF (10 µg per lane) for 30 minutes. HNPs bound to VWF multimers were detected by western blotting with mouse anti-HNP1-3 IgG (green, on the left), followed by Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-mouse IgG after electrophoresis with 1% agarose gel. VWF multimers were detected on the same membrane by incubation with rabbit anti-human VWF IgG (red, in the middle), followed by Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (red). The merged image (HNP1/VWF) is shown on the right. (D) Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated native HNPs (green, on the left) (1 µg/mL) were incubated with cultured HUVECs on a BioFlux microfluidic channel after stimulation with histamine (100 µM) for 2 minutes under flow (5 dyne/cm2). The fluorescent images were obtained after fixation of HUVECs with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and stained with Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated rabbit anti-VWF IgG (1:1000) (red, in the middle). The merged image (HNP1/ULVWF) is shown on the right.

Native HNPs bind to GST-VWF73-H, soluble VWF, and ultra-largeVWF on endothelial cells under flow. Purified native HNPs (0-6 µM) were flown on a CM5 surface covalently immobilized with purified recombinant GST-VWF73-H peptide (A) and multimeric VWF (B) under the flow rate of 20 µL per minute for 10 minutes. The bound HNPs are demonstrated by the increase in response units (RU) as a function of time. The representative curves of 3 independent experiments are shown. The dissociation constants KD (s) were determined by fitting the sensorgrams using the 1:1 Langmuir interaction model. (C) Purified native HNPs (0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.0, and 2.0 µg per lane) were incubated with purified plasma VWF (10 µg per lane) for 30 minutes. HNPs bound to VWF multimers were detected by western blotting with mouse anti-HNP1-3 IgG (green, on the left), followed by Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-mouse IgG after electrophoresis with 1% agarose gel. VWF multimers were detected on the same membrane by incubation with rabbit anti-human VWF IgG (red, in the middle), followed by Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (red). The merged image (HNP1/VWF) is shown on the right. (D) Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated native HNPs (green, on the left) (1 µg/mL) were incubated with cultured HUVECs on a BioFlux microfluidic channel after stimulation with histamine (100 µM) for 2 minutes under flow (5 dyne/cm2). The fluorescent images were obtained after fixation of HUVECs with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and stained with Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated rabbit anti-VWF IgG (1:1000) (red, in the middle). The merged image (HNP1/ULVWF) is shown on the right.

Plasma levels of HNPs are markedly increased in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP

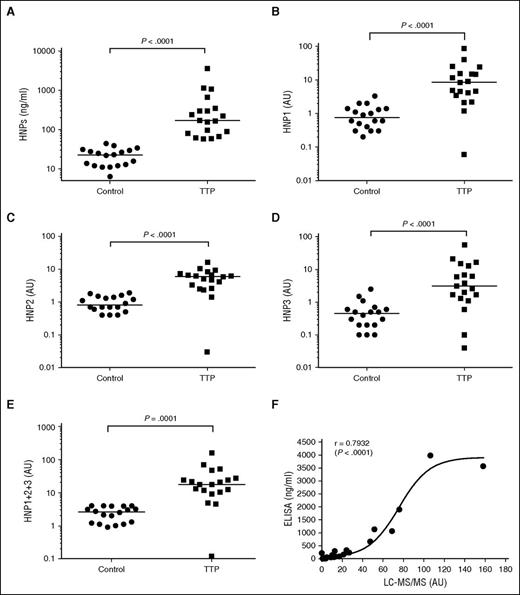

To assess whether HNPs released from activated neutrophils might play a role in triggering TTP, we measured plasma levels of HNPs in 19 patients (mean age, 42 years) with autoimmune TTP and 18 healthy controls by ELISA and LC-MS/MS assays. Fifteen patient samples (∼80%) were collected at the time of their initial presentation and the remainder were collected upon relapse. The median platelet counts of these patients were 15 000/μL (range, 6000-40 000/μL) and all except 2 had plasma ADAMTS13 activity of <5% (ranging from <5% to 8%) (Table 1). A commercial ELISA was used to measure total plasma levels of HNPs1-3, whereas LC-MS/MS was used to detect HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 separately based on the m/z ratio and the peptide fragmentation after the most abundant proteins were removed by acid precipitation. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 5, the median plasma levels of HNPs1-3 in TTP patients during the acute episodes were ∼170 ng/mL (58-3570 ng/mL, n = 19), significantly higher than those in healthy controls ∼23 ng/mL (6-44 ng/mL, n = 18) (Table 1; Figure 5A). The difference between HNP levels in the 2 groups was statistically highly significant (P < .0001). The median plasma levels of HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 were 8.4 AU/mL (Figure 5B), 6.0 AU/mL (Figure 5C), and 3.1 AU/mL (Figure 5D), respectively, in the same TTP patients, ∼6- to 11-fold higher than those in the healthy controls (∼1 AU/mL) (Table 1). There was a good correlation between ELISA and LC-MS/MS for measuring HNPs1-3 with a Spearman rank correction coefficient (ρ) of 0.7932 (P < .0001). The sigmoidal curve suggests a better sensitivity by LC-MS/MS than by ELISA for the measurement of low levels of HNPs1-3 in human plasma (Figure 5E).

Clinical and laboratory data of TTP patients

| Serial no. . | Age, y . | TTP diagnosis . | Platelet count, ×109/L . | ADAMTS13 activity, % . | Relative abundance, AU . | LC/MS HNP1+2+3, AU . | ELISA HNPs, ng/mL . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNP1 . | HNP2 . | HNP3 . | |||||||

| 1 | 42 | Initial | 16 | <5 | 85.2 | 16.1 | 56.8 | 158.1 | 3570.0 |

| 2 | 56 | Initial | 19 | <5 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 17.4 | 96.7 |

| 3 | 50 | Initial | 6 | <5 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 220.1 |

| 4 | 27 | Initial | 24 | 5.4 | 39.8 | 7.7 | 21.3 | 68.8 | 1071.2 |

| 5 | 84 | Initial | 30 | <5 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 67.2 |

| 6 | 38 | Initial | 10 | <5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 10.3 | 156.6 |

| 7 | 38 | Initial | 15 | <5 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 11.8 | 61.7 |

| 8 | 28 | Initial | 7 | 8 | 25.3 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 47.6 | 669.6 |

| 9 | 58 | Initial | 14 | <5 | 14.8 | 6.6 | 0.1 | 21.4 | 164.9 |

| 10 | 40 | Initial | 22 | <5 | 2.2 | 6.8 | 15.1 | 24.1 | 295.7 |

| 11 | 23 | Initial | 11 | <5 | 15.3 | 8.3 | 0.6 | 24.2 | 346.3 |

| 12 | 33 | Initial | 13 | <5 | 11.6 | 6.3 | 3.1 | 21.0 | 170.4 |

| 13 | 57 | Initial | 11 | <5 | 24.4 | 10.4 | 16.7 | 51.5 | 1136.6 |

| 14 | 28 | Initial | 38 | <5 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 5.9 | 12.6 | 300.3 |

| 15 | 42 | Initial | 16 | <5 | 14.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 27.0 | 240.4 |

| 16 | 44 | Relapsed | 15 | <5 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 17.4 | 80.1 |

| 17 | 46 | Relapsed | 40 | <5 | 9.0 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 13.3 | 90.3 |

| 18 | 77 | Relapsed | 11 | <5 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 4.5 | 58.0 |

| 19 | 40 | Relapsed | 21 | <5 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 9.1 | 58.9 |

| Median (range) | 42 (23-84) | NA | 15 (6-40) | 6.7 (<5-8) | 8.4 (0.1-85.2) | 6.0 (0.03-16.1) | 3.1 (0.04-56.8) | 17.4 (0.1-158.1) | 170.4 (58.0-3570.0) |

| Serial no. . | Age, y . | TTP diagnosis . | Platelet count, ×109/L . | ADAMTS13 activity, % . | Relative abundance, AU . | LC/MS HNP1+2+3, AU . | ELISA HNPs, ng/mL . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNP1 . | HNP2 . | HNP3 . | |||||||

| 1 | 42 | Initial | 16 | <5 | 85.2 | 16.1 | 56.8 | 158.1 | 3570.0 |

| 2 | 56 | Initial | 19 | <5 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 17.4 | 96.7 |

| 3 | 50 | Initial | 6 | <5 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 220.1 |

| 4 | 27 | Initial | 24 | 5.4 | 39.8 | 7.7 | 21.3 | 68.8 | 1071.2 |

| 5 | 84 | Initial | 30 | <5 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 67.2 |

| 6 | 38 | Initial | 10 | <5 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 10.3 | 156.6 |

| 7 | 38 | Initial | 15 | <5 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 11.8 | 61.7 |

| 8 | 28 | Initial | 7 | 8 | 25.3 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 47.6 | 669.6 |

| 9 | 58 | Initial | 14 | <5 | 14.8 | 6.6 | 0.1 | 21.4 | 164.9 |

| 10 | 40 | Initial | 22 | <5 | 2.2 | 6.8 | 15.1 | 24.1 | 295.7 |

| 11 | 23 | Initial | 11 | <5 | 15.3 | 8.3 | 0.6 | 24.2 | 346.3 |

| 12 | 33 | Initial | 13 | <5 | 11.6 | 6.3 | 3.1 | 21.0 | 170.4 |

| 13 | 57 | Initial | 11 | <5 | 24.4 | 10.4 | 16.7 | 51.5 | 1136.6 |

| 14 | 28 | Initial | 38 | <5 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 5.9 | 12.6 | 300.3 |

| 15 | 42 | Initial | 16 | <5 | 14.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 27.0 | 240.4 |

| 16 | 44 | Relapsed | 15 | <5 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 17.4 | 80.1 |

| 17 | 46 | Relapsed | 40 | <5 | 9.0 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 13.3 | 90.3 |

| 18 | 77 | Relapsed | 11 | <5 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 4.5 | 58.0 |

| 19 | 40 | Relapsed | 21 | <5 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 9.1 | 58.9 |

| Median (range) | 42 (23-84) | NA | 15 (6-40) | 6.7 (<5-8) | 8.4 (0.1-85.2) | 6.0 (0.03-16.1) | 3.1 (0.04-56.8) | 17.4 (0.1-158.1) | 170.4 (58.0-3570.0) |

All patients received plasma exchange therapy. All samples were collected prior to the first therapeutic plasma exchange.

Plasma levels of HNP1-3 and subtypes (HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3) in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP. (A) Plasma levels of HNP1-3 in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP and healthy controls as determined by ELISA. (B-E) The plasma levels of HNP1, HNP2, HNP3, and total HNP1+2+3, respectively, in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP and healthy controls as determined by LC-MS/MS. The relative abundance of HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 in TTP patients was determined by comparing with that in the mean value of each HNP in normal human plasma (defined as having 1 AU/mL). (F) The Spearman rank correction coefficient (ρ = 0.7932) between LC-MS/MS and ELISA for measurement of total plasma levels of HNP1-3 using GraphPad Prism 6. P values <.05 and .01 are considered to be statistically significant and highly significant.

Plasma levels of HNP1-3 and subtypes (HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3) in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP. (A) Plasma levels of HNP1-3 in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP and healthy controls as determined by ELISA. (B-E) The plasma levels of HNP1, HNP2, HNP3, and total HNP1+2+3, respectively, in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP and healthy controls as determined by LC-MS/MS. The relative abundance of HNP1, HNP2, and HNP3 in TTP patients was determined by comparing with that in the mean value of each HNP in normal human plasma (defined as having 1 AU/mL). (F) The Spearman rank correction coefficient (ρ = 0.7932) between LC-MS/MS and ELISA for measurement of total plasma levels of HNP1-3 using GraphPad Prism 6. P values <.05 and .01 are considered to be statistically significant and highly significant.

Discussion

HNPs exert diverse protective biological activities, including direct microbial killing30 and immunomodulation.31 However, HNPs can also exert adverse effects on the host as they promote platelet aggregation,16 cause endothelial dysfunction,32 inhibit fibrinolysis,17 and induce a post-translational modification of low-density lipoprotein that promotes atherosclerosis at normal levels of plasma cholesterol.33 Here, we show that HNPs inhibit the proteolytic cleavage of the minimal substrate VWF73 and multimeric VWF by ADAMTS13 under diverse conditions (Figures 1 and 2). This inhibitory activity appeared to be mediated by high-affinity binding of HNPs to the central A2 domain of VWF (ie, VWF73) through the RRY motif (Figure 3). These 3 residues RRY are also present in the spacer domain of ADAMTS13 that is known to interact with the terminal 9 amino acid residues in the VWF73 peptide, which is essential for ADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis of the peptidyl substrate.34 Based on modeling, we hypothesize that the RRY residues in HNPs1-3 may interact directly with E1660 and D1663 residues in the VWF73 peptide and VWF (Figure 3), physically blocking the binding of the spacer domain (RRY) of ADAMTS13 to the substrates, and thereby inhibiting proteolysis of VWF by ADAMTS13 under the assay conditions described.

HNPs have the ability to dimerize, oligomerize, and multimerize on targeted surfaces of bacterial, viral, and host origin.13 An impaired ability of HNP1 to dimerize correlates with its reduced antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, inhibition of anthrax lethal factor, and impaired binding to HIV-1 gp120.35 However, it remains to be determined whether this propensity of HNPs to oligomerize contributes to its inhibitory potency on ADAMTS13-dependent proteolysis of VWF. The much lower KD assessed by the binding assay (Figure 4) than the IC50 in the functional assays (Figure 2) suggests the possibility of multiple binding sites on VWF. However, only the binding to the central A2 domain (ie, VWF73) results in inhibition of VWF proteolysis by ADAMTS13. Moreover, the oligomerization or multimerization of HNPs may also contribute to the lower apparent KD than IC50 values.

The physiological relevance of HNP-mediated inhibition of VWF proteolysis by ADAMTS13 is implicated by the significant elevation of plasma levels of HNPs in patients with acquired autoimmune TTP at the time of acute clinical presentation (Table 1; Figure 5). Neutrophil activation and degranulation, indicated by increases in circulating DNA and myeloperoxidase, have been reported in patients with acute thrombotic microangiopathy, which appeared to correlate with the disease activity.36 In non-TTP patients, plasma levels of HNPs increased by twofold to fourfold following infection37 and levels increase to 900∼170 000 ng/mL during sepsis.14 Although elevated plasma HNPs might not suffice to promote microvascular thrombosis in patients with normal or modestly reduced levels of circulating ADAMTS13 activity, they may tip the clinical balance in patients with congenital or acquired autoimmune TTP in whom severe deficiency of plasma ADAMTS13 activity already compromises proteolysis of ultra-large VWF on the endothelial cell surface, in the circulation and at sites of vascular injury. Thus, at sites of vascular injury or inflammation, where platelets and neutrophils accumulate,38,39 the local release of HNPs helps limit dissemination of infection but local binding of HNPs to VWF released from activated endothelial cells may suppress residual perivascular ADAMTS13 activity and thereby predispose to thrombosis.

In addition to inhibiting VWF proteolysis, HNPs have also been shown to activate platelets by promoting binding to fibrinogen and thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) amyloid-like structure.16 This results in secretion of platelet granule contents, shedding of soluble CD40 ligand, and expression of platelet surface procoagulant activity.16 Furthermore, HNPs can modulate the binding of tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen to fibrin and endothelial cells, which inhibits fibrinolysis.17 Together, these results indicate that HNPs may be a family of potent proinflammatory and prothrombotic peptides that not only contributes to host defense against microbial invasion, but also promotes clinically significant microvascular thrombosis in settings such as TTP where circulating ADAMTS13 is already limited.

It remains unclear, however, whether the released HNPs trigger the formation of autoantibodies against ADAMTS13. Our fine-mapping study of anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies demonstrated that the RRY motif in the spacer domain of ADAMTS13 is the frequent target of anti-ADAMTS13 IgGs in patients with acquired TTP.40 HNPs share the same motif that is present in the ADAMTS13-spacer domain; therefore, it is possible that the released HNPs may boost the formation of a specific pathogenic autoantibody that binds the exosite 3 (RRYGEE) in the spacer domain of ADAMTS13. A monoclonal anti-human IgG (scFv4-20) isolated by phage display from a patient with acquired TTP appears to bind HNPs (not shown). HNPs have been shown to stimulate production of other autoantibodies indirectly by modulating inflammatory responses and the adaptive immune system by functioning as potent chemotaxins for mononuclear cells,41 dendritic cells, and CD45RA+ and CD8 T lymphocytes.42

Several limitations of our studies should be noted. Activation of complement,43,44 cytokines, and other inflammatory pathways45 may also contribute to the development of thrombosis in TTP, as suggested by the variation in plasma HNPs1-3 levels in patients at presentation. Additional larger serial studies will be needed to determine whether a rise in plasma levels of HNPs precedes presentation, correlates with response, and predicts relapse. Local release, binding, and retention of HNPs at sites of vascular injury are likely to exceed expectations based on plasma levels.33 Lastly, studies under way in mice transgenic for neutrophil expression of HNP133,46 are needed to more definitively assess the role of these peptides in propagating thrombosis in the setting of antibody-mediated deficiency of ADAMTS13 activity.47,48

In summary, we demonstrate that HNPs are potent inhibitors of ADAMTS13-dependent VWF proteolysis in vitro. The inhibitory activity of HNPs appears to depend on the presence of the RRY motif, which presumably mediates direct binding to the central A2 domain of VWF and physically blocks the interactions between ADAMTS13 and VWF. This results in impaired proteolysis of the substrate, further limiting the efficacy of the residual ADAMTS13 activity. Moreover, the increased levels of HNPs1-3 found in the plasma of most TTP patients at the time of clinical presentation support the potential contribution of HNP-mediated inhibition of ADAMTS13 activity to the pathogenesis of acquired autoimmune TTP and identifies a potential new therapeutic target such as colchicine to inhibit the release of HNPs33 in the treatment and prevention of disease relapse.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Answering T.T.P. Foundation and National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01HL115187-01A1 and R01HL126724-01 (X.L.Z.), R56-HL123912 (D.B.C.), and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant R21NS091793-01 (K.B.).

Authorship

Contribution: V.G.P., J.B., D.B.C., and X.L.Z. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; and C.B.Z., J.K.M., P.S.C., S.H.S., and K.B. performed experiments, analyzed the data, and helped revise the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: X.L.Z. has been on the speaker bureau for Alexion and a consultant for Ablynx, and received research funds from Lee’s Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: X. Long Zheng, Division of Laboratory Medicine, Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, WPP230, 619 19th St South, Birmingham, AL 35249-7331; e-mail: xzheng@uabmc.edu.

References

Author notes

V.G.P. and J.B. contributed equally to this study.