Key Points

Low doses of the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib are highly effective in refractory hairy cell leukemia.

Abrogation of BRAF V600E–induced signaling was consistently seen with 240 mg of vemurafenib twice daily.

Abstract

The activating mutation of the BRAF serine/threonine protein kinase (BRAF V600E) is the key driver mutation in hairy cell leukemia (HCL), suggesting opportunities for therapeutic targeting. We analyzed the course of 21 HCL patients treated with vemurafenib outside of trials with individual dosing regimens (240-1920 mg/d; median treatment duration, 90 days). Vemurafenib treatment improved blood counts in all patients, with platelets, neutrophils, and hemoglobin recovering within 28, 43, and 55 days (median), respectively. Complete remission was achieved in 40% (6/15 of evaluable patients) and median event-free survival was 17 months. Response rate and kinetics of response were independent of vemurafenib dosing. Retreatment with vemurafenib led to similar response patterns (n = 6). Pharmacodynamic analysis of BRAF V600E downstream targets showed that vemurafenib (480 mg/d) completely abrogated extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation of hairy cells in vivo. Typical side effects also occurred at low dosing regimens. We observed the development of acute myeloid lymphoma (AML) subtype M6 in 1 patient, and the course suggested disease acceleration triggered by vemurafenib. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase hotspot mutation (E545K) was identified in the AML clone, providing a potential novel mechanism for paradoxical BRAF activation. These data provide proof of dependence of HCL on active BRAF signaling. We provide evidence that antitumor and side effects are observed with 480 mg vemurafenib, suggesting that dosing regimens in BRAF-driven cancers could warrant reassessment in trials with implications for cost of cancer care.

Introduction

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a mature B-cell lymphoid malignancy presenting with pancytopenia and splenomegaly.1-3 Standard treatment is based on chemotherapy with purine analogs,1,2 but eradication of minimal residual disease is rarely achieved by purine analogs alone.4

Gain-of-function mutations of the BRAF serine/threonine protein kinase (BRAF V600E) have been identified in 95% to 100% of classical HCL.5,6 The incidence and the presence in all malignant B cells5,7 suggest that HCL cells critically depend on activated BRAF, providing oncogenic signaling through the MEK–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade.5,8 Data from trials in BRAF-mutated melanomas9,10 have inspired investigators to treat refractory HCL patients with the BRAF inhibitor (BRAFi) vemurafenib, which showed striking clinical activity.11-15 Dosing of vemurafenib outside clinical trials has been significantly lower than standard melanoma dosing (240 mg twice daily vs 960 mg twice daily).12,16 Two phase 2 trials (an Italian trial [n = 26] and a US trial [n = 24]) have explored the melanoma dose of 2 × 960 mg and demonstrated efficacy in all treated patients.17 Despite improvement of blood counts in all patients, complete remission (CR) was achieved by only 35% to 42% of patients. Assessment of minimal residual disease revealed persisting hairy cells, even in patients with CR.17

Maximum tolerated dose traditionally serves as the primary end point for the majority of dose-finding studies, but on-target efficacy often occurs at lower doses. Indeed, dosing of cancer cell–specific drugs may be best assessed by on-target inhibition, response, and safety.18,19 Dose finding of vemurafenib in BRAF-mutant melanoma was based on dose-limiting toxicities occurring in <30% of patients, but objective responses were observed at the first dose escalation level of 2 × 240 mg.9

In the current study, we collected a series of HCL patients with long-term follow-up who have been treated at our centers. The data provide conclusive evidence that low doses of vemurafenib are active in HCL. Based on the presence of typical side effects, as well as clinical and experimental evidence for sufficient on-target activity, the data suggest that systematic dose reconsideration is warranted in HCL and potentially other BRAF-mutant cancers, which could significantly reduce cost of care.

Methods

Data collection and response definition

We report on 21 patients with classical HCL treated with vemurafenib in 11 different European centers (Heidelberg, n = 6; Innsbruck, n = 4; Nice, n = 2; Munich, n = 2; Cambridge, n = 1; Erfurt, n = 1; Freiburg, n = 1; Lucerne, n = 1; Cologne, n = 1; Leicester, n = 1; and London, n = 1) outside of trials from 2011 to 2014. Five patients have previously been reported and are included with updated follow-up.12-14,20,21 Clinical data and follow-up information were collected by chart review. Bone marrow slides were centrally reviewed (n = 11, by M.A.). Trephine biopsies were not available for 4 of 15 patients. For these 4 patients, pathology reports were carefully reviewed. Responses were evaluated based on blood counts, bone marrow findings, and peripheral blood hairy cell count using standard criteria.1 CR was achieved when the platelet counts were >100 000/μL, hemoglobin level was >12 g/dL, neutrophil counts were >1000/μL, spleen size had normalized, and bone marrow biopsy was negative for hairy cells. For the definition of CR, the evaluation of trephine biopsy samples and peripheral blood smears had to be negative for hairy cells, at least based on morphology using nonimmunologic stains.

Median time between start of vemurafenib treatment and bone marrow biopsy was 3 months (range, 1.0-11.1 months). Bone marrow biopsies were performed in the context of recovered blood counts.

To determine spleen size, we used the largest diameter of the spleen, which correlates well with its volumes.22 Spleen sizes were measured by ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography. We used a cutoff for splenomegaly of >13 cm.22 In 1 patient for whom no ultrasound or other imaging studies were performed, we report reduction of spleen sizes based on physical examination.

Histological findings

Immunohistochemistry for PAX5/phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), glycophorin/p-ERK, and cyclin D1 were performed according to standard methods (see supplemental Materials and Methods, available on the Blood Web site). Anti-BRAF V600E immunostaining was done as described previously using the monoclonal mouse antibody VE1.23

Further methods are provided in supplemental Materials and Methods.

Results

Patient characteristics, vemurafenib dosing, and treatment

The presence of the BRAF V600E mutation was demonstrated in all patients by immunohistochemical staining (BRAF V600E mutation–specific antibody) (n = 6) and/or sequencing (n = 15). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Median age at initiation of vemurafenib was 64 years (range, 45-89 years). Median time from diagnosis to treatment was 8 years (range, 0-31 years). Patients were heavily pretreated (median of 3 prior treatment lines; range, 0-12 lines; n = 19). Indication for treatment was based on presence of cytopenia in all patients (thrombocytopenia <100 000/μL, n = 19/21; hemoglobin <10 g/dL, n = 15/21; or neutrophils <1000/μL, n = 18/21). Based on these criteria, trilineage cytopenias were observed in 14 of 21 patients and bilineage cytopenias in 3 of 21 patients. Two patients were treated with vemurafenib as first-line therapy. Vemurafenib dose was chosen by the authors independently, which allowed us to compare the effect of dose levels. A dose of 240 mg twice daily was used in 17 patients. Twelve patients continued at this dose, whereas doses were escalated in 5 patients (480 mg, n = 1; 720 mg, n = 2; and 960 mg, n = 2; all twice daily). Further patients received 240 mg once daily (n = 1), 480 mg twice daily (n = 2), or 960 mg twice daily (n = 1) without dose modification. No information on why doses were escalated was available. Median duration of treatment was 90 days (range, 56-266 days), with a median cumulative treatment dose of 51 000 mg (range, 27 000-311 000 mg). Discontinuation of therapy with vemurafenib was based on physicians’ choices and on full recovery of blood counts in 20 of 21 patients. One patient developed an acute myeloid lymphoma (AML) subtype M6 with concomitant deteriorating liver function tests, and vemurafenib was subsequently stopped.

Patient characteristics and follow-up of patients with HCL treated with vemurafenib

| Patient . | Age, y . | Lines prior treatment . | Treatment duration, d . | Starting dose, mg . | Dose escalation . | Cumulative dose, mg . | Response . | Hairy cells after BRAFi in BM, % . | Spleen before BRAFi, cm . | Spleen after BRAFi, cm . | Side effects . | Follow-up, mo . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heidelberg 01 | 51 | 3 | 56 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 960 mg/d | 68 640 | CR | 0 | 25 | 13 | Arthralgia, elevated LFTs | 38 | Retreatment |

| Heidelberg 02 | 60 | 4 | 86 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 720 mg/d | 113 760 | PR | 10 | 17 | 15 | Arthralgia, elevated LFTs | 21 | Retreatment |

| Heidelberg 03 | 56 | 4 | 91 | 2 × 240 | No | 43 680 | PR | 40 | 22 | 10 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 26 | Retreatment |

| Heidelberg 04 | 69 | 3 | 89 | 2 × 240 | No | 42 720 | CR | 0 | 16 | 12 | No major | 17 | |

| Heidelberg 05 | 59 | 3 | 129 | 2 × 240 | No | 61 920 | NA | Not enlarged | Keratoacanthoma, arthralgia, skin phototoxicity | 14 | Retreatment | ||

| Heidelberg 06 | 45 | 1 | 88 | 2 × 240 | No | 42 240 | PR | 40 | 18 | 15 | No major | 11 | |

| Nice 01 | 74 | 2 | 90 | 2 × 240 | No | 43 200 | NA | NA | No major | 25 | Retreatment | ||

| Nice 02 | 49 | 0 | 57 | 2 × 240 | No | 27 360 | NA | 21 | 13 | No major | 15 | Retreatment | |

| Cambridge | 68 | 4 | 58 | 2 × 240 | No | 27 840 | NA | Splenectomy | Elevated LFTs, keratoacanthoma | 31 | Retreatment | ||

| Erfurt | 51 | 4 | 106 | 2 × 240 | No | 50 880 | PR | 40 | 6 cm BCM | Not palpable | No major | 17 | |

| Freiburg | 62 | 3 | 85 | 2 × 960 | No | 81 600 | CR | 0 | NA | No major | 9 | ||

| Lucerne | 50 | 5 | 56 | 2 × 240 | No | 26 880 | MR | 40 | Splenectomy | AML-M6 | 17 | Death | |

| Innsbruck 01 | 79 | 3 | 104 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 480 mg/d | 96 480 | CR | 0 | 18 | 12 | No major | 20 | |

| Innsbruck 02 | 69 | 0 | 142 | 2 × 480 | No | 68 160 | PR | 8 | 14 | 12 | Elevated LFTs, keratoacanthoma | 17 | Retreatment |

| Innsbruck 03 | 71 | 1 | 108 | 2 × 480 | No | 51 840 | CR | 0 | 12 | 12 | No major | 10 | |

| Innsbruck 04 | 67 | 12 | 112 | 1 × 240 | No | 26 880 | NA | 15 | 13 | Skin phototoxicity | 8 | Retreatment | |

| Cologne | 65 | 5 | 83 | 2 × 240 | No | 39 840 | PR | 5 | Splenectomy | No major | 10 | ||

| Leicester | 72 | 5 | 167 | 2 × 240 | No | 80 160 | PR | 4 | Splenectomy | Alopecia, squamous cell papilloma of the skin, skin phototoxicity | 10 | Death | |

| Schwabing 1 | 61 | 1 | 266 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 720 mg/d | 264 240 | CR | 0 | 18 | 12 | No major | 10 | |

| Schwabing 2 | 89 | 2 | 68 | 2 × 240 | No | 32 640 | NA | NA | Acute on chronic renal failure, exicosis | 3 | Death | ||

| London | 48 | 6 | 167 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 960 mg/d | 310 560 | PR | 10 | Splenectomy | Arthralgias, skin phototoxicity | 20 |

| Patient . | Age, y . | Lines prior treatment . | Treatment duration, d . | Starting dose, mg . | Dose escalation . | Cumulative dose, mg . | Response . | Hairy cells after BRAFi in BM, % . | Spleen before BRAFi, cm . | Spleen after BRAFi, cm . | Side effects . | Follow-up, mo . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heidelberg 01 | 51 | 3 | 56 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 960 mg/d | 68 640 | CR | 0 | 25 | 13 | Arthralgia, elevated LFTs | 38 | Retreatment |

| Heidelberg 02 | 60 | 4 | 86 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 720 mg/d | 113 760 | PR | 10 | 17 | 15 | Arthralgia, elevated LFTs | 21 | Retreatment |

| Heidelberg 03 | 56 | 4 | 91 | 2 × 240 | No | 43 680 | PR | 40 | 22 | 10 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 26 | Retreatment |

| Heidelberg 04 | 69 | 3 | 89 | 2 × 240 | No | 42 720 | CR | 0 | 16 | 12 | No major | 17 | |

| Heidelberg 05 | 59 | 3 | 129 | 2 × 240 | No | 61 920 | NA | Not enlarged | Keratoacanthoma, arthralgia, skin phototoxicity | 14 | Retreatment | ||

| Heidelberg 06 | 45 | 1 | 88 | 2 × 240 | No | 42 240 | PR | 40 | 18 | 15 | No major | 11 | |

| Nice 01 | 74 | 2 | 90 | 2 × 240 | No | 43 200 | NA | NA | No major | 25 | Retreatment | ||

| Nice 02 | 49 | 0 | 57 | 2 × 240 | No | 27 360 | NA | 21 | 13 | No major | 15 | Retreatment | |

| Cambridge | 68 | 4 | 58 | 2 × 240 | No | 27 840 | NA | Splenectomy | Elevated LFTs, keratoacanthoma | 31 | Retreatment | ||

| Erfurt | 51 | 4 | 106 | 2 × 240 | No | 50 880 | PR | 40 | 6 cm BCM | Not palpable | No major | 17 | |

| Freiburg | 62 | 3 | 85 | 2 × 960 | No | 81 600 | CR | 0 | NA | No major | 9 | ||

| Lucerne | 50 | 5 | 56 | 2 × 240 | No | 26 880 | MR | 40 | Splenectomy | AML-M6 | 17 | Death | |

| Innsbruck 01 | 79 | 3 | 104 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 480 mg/d | 96 480 | CR | 0 | 18 | 12 | No major | 20 | |

| Innsbruck 02 | 69 | 0 | 142 | 2 × 480 | No | 68 160 | PR | 8 | 14 | 12 | Elevated LFTs, keratoacanthoma | 17 | Retreatment |

| Innsbruck 03 | 71 | 1 | 108 | 2 × 480 | No | 51 840 | CR | 0 | 12 | 12 | No major | 10 | |

| Innsbruck 04 | 67 | 12 | 112 | 1 × 240 | No | 26 880 | NA | 15 | 13 | Skin phototoxicity | 8 | Retreatment | |

| Cologne | 65 | 5 | 83 | 2 × 240 | No | 39 840 | PR | 5 | Splenectomy | No major | 10 | ||

| Leicester | 72 | 5 | 167 | 2 × 240 | No | 80 160 | PR | 4 | Splenectomy | Alopecia, squamous cell papilloma of the skin, skin phototoxicity | 10 | Death | |

| Schwabing 1 | 61 | 1 | 266 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 720 mg/d | 264 240 | CR | 0 | 18 | 12 | No major | 10 | |

| Schwabing 2 | 89 | 2 | 68 | 2 × 240 | No | 32 640 | NA | NA | Acute on chronic renal failure, exicosis | 3 | Death | ||

| London | 48 | 6 | 167 | 2 × 240 | 2 × 960 mg/d | 310 560 | PR | 10 | Splenectomy | Arthralgias, skin phototoxicity | 20 |

Spleen sizes were measured by imaging studies and were not considered enlarged if the largest diameter was <13 cm. No imaging studies were performed in 1 patient, for whom spleen sizes are reported in centimeters BCM, or not palpable.

BCM, below costal margin; BM, bone marrow; LFTs, liver function tests; MR, minor response; NA, not available; PR, partial remission.

Vemurafenib treatment and response

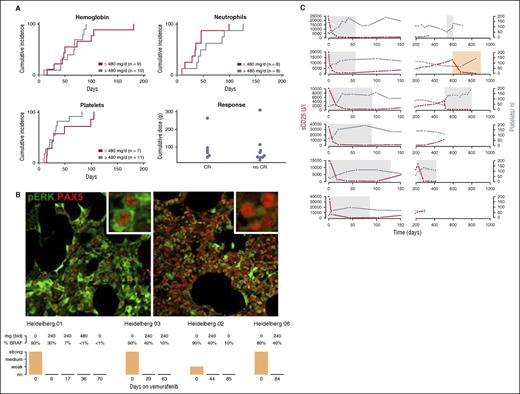

Blood counts improved in all patients (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1). Platelets recovered first (median time to platelets >100.000/μL, 28 days; range, 10-105 days). Median time to recovery of neutrophils (>1000/μL) was 43 days (range, 9-126 days) and median time to hemoglobin recovery (>12 g/dL) was 55 days (range, 10-181 days) (Figure 1A). There was no detectable difference in recovery of blood count dynamics for patients who received low doses of vemurafenib (≤240 mg, Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1). In addition, treatment duration as a continuous variable did not have an impact on reconstitution of blood counts (platelets, P = .15; hemoglobin, P = .13; and neutrophils, P = .284).

Effect of vemurafenib in HCL. (A) Cumulative incidence of blood count improvement. Upper row and lower left image: cumulative incidence of patients achieving hemoglobin >12 g/dL, neutrophils >1000 μL, and platelets >100/nL on vemurafenib treatment. Nineteen of 21 patients had thrombocytopenia <100 000/μL, and platelet counts improved above this threshold on vemurafenib treatment in all 19 patients. Hemoglobin levels were <10 g/dL in 15 of 21 patients and <12 g/dL in 20 of 21 patients. Hemoglobin levels improved in 19 of 20 patients with vemurafenib, but 1 patient developed AML-M6 and did not improve above this threshold. Eighteen of 21 patients had neutropenia <1000/μL and improved with vemurafenib treatment above this threshold. There was no difference in recovery of blood counts of patients who received low (≤240 mg twice daily) or high doses of vemurafenib (>240 mg twice daily) (hemoglobin, P = .38; platelets, P = .25; neutrophils, P = .24). Lower right panel (Response): cumulative vemurafenib doses of patients who achieved a CR and partial remission (P = .67; OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.03; effect 1000 mg). Patients who achieved a CR did not receive higher cumulative doses of vemurafenib. (B) Bone marrow findings during vemurafenib treatment: PAX5 (nuclear stain, red) and p-ERK (cytoplasmatic stain, green) of trephine biopsy material before (upper left picture) and during (upper right picture) vemurafenib treatment (Heidelberg 01, day 6). P-ERK was undetectable upon vemurafenib treatment in hairy cells (n = 4). Hairy cell infiltration (BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry) decreased with diverse kinetics. The complete abrogation of p-ERK in PAX5-positive cells with 240 mg of vemurafenib suggests sufficient on-target activity. (C) Disease course summarized by sCD25 and platelet dynamics: sCD25 levels (U/L) and platelet counts during and after vemurafenib treatment are shown (n = 6; top to bottom: Heidelberg 01-06). Gray boxes show the vemurafenib treatment interval. Four patients received low-dose vemurafenib (240 mg twice daily). Patient Heidelberg 01 had escalated dosing from day 17 (days 17-36, 480 mg twice daily; days 37-56, 720 mg twice daily; days 57-58, 960 mg twice daily) and patient Heidelberg 02 received 480 mg twice daily (days 23-43) and 720 mg twice daily (days 44-51). sCD25 decreased to normal levels upon vemurafenib treatment in all patients. After cessation of vemurafenib, sCD25 levels rose, exhibiting individual progression patterns (yellow box indicates rituximab and pentostatin treatment).

Effect of vemurafenib in HCL. (A) Cumulative incidence of blood count improvement. Upper row and lower left image: cumulative incidence of patients achieving hemoglobin >12 g/dL, neutrophils >1000 μL, and platelets >100/nL on vemurafenib treatment. Nineteen of 21 patients had thrombocytopenia <100 000/μL, and platelet counts improved above this threshold on vemurafenib treatment in all 19 patients. Hemoglobin levels were <10 g/dL in 15 of 21 patients and <12 g/dL in 20 of 21 patients. Hemoglobin levels improved in 19 of 20 patients with vemurafenib, but 1 patient developed AML-M6 and did not improve above this threshold. Eighteen of 21 patients had neutropenia <1000/μL and improved with vemurafenib treatment above this threshold. There was no difference in recovery of blood counts of patients who received low (≤240 mg twice daily) or high doses of vemurafenib (>240 mg twice daily) (hemoglobin, P = .38; platelets, P = .25; neutrophils, P = .24). Lower right panel (Response): cumulative vemurafenib doses of patients who achieved a CR and partial remission (P = .67; OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.03; effect 1000 mg). Patients who achieved a CR did not receive higher cumulative doses of vemurafenib. (B) Bone marrow findings during vemurafenib treatment: PAX5 (nuclear stain, red) and p-ERK (cytoplasmatic stain, green) of trephine biopsy material before (upper left picture) and during (upper right picture) vemurafenib treatment (Heidelberg 01, day 6). P-ERK was undetectable upon vemurafenib treatment in hairy cells (n = 4). Hairy cell infiltration (BRAF V600E immunohistochemistry) decreased with diverse kinetics. The complete abrogation of p-ERK in PAX5-positive cells with 240 mg of vemurafenib suggests sufficient on-target activity. (C) Disease course summarized by sCD25 and platelet dynamics: sCD25 levels (U/L) and platelet counts during and after vemurafenib treatment are shown (n = 6; top to bottom: Heidelberg 01-06). Gray boxes show the vemurafenib treatment interval. Four patients received low-dose vemurafenib (240 mg twice daily). Patient Heidelberg 01 had escalated dosing from day 17 (days 17-36, 480 mg twice daily; days 37-56, 720 mg twice daily; days 57-58, 960 mg twice daily) and patient Heidelberg 02 received 480 mg twice daily (days 23-43) and 720 mg twice daily (days 44-51). sCD25 decreased to normal levels upon vemurafenib treatment in all patients. After cessation of vemurafenib, sCD25 levels rose, exhibiting individual progression patterns (yellow box indicates rituximab and pentostatin treatment).

Hematological response was achieved in 20 of 21 patients (95%). The 1 patient failing to meet these criteria developed AML-M6 after vemurafenib treatment, resulting in inefficient erythropoiesis (see “Side effects during vemurafenib treatment”), whereas platelet and neutrophil counts improved sufficiently to meet response criteria. Based on response assessment of bone marrow trephine biopsy samples, 6 of 15 patients achieved a CR. Although response criteria were otherwise achieved, 6 patients had no trephine biopsy, and formal response could not be determined.

In logistic regression analysis, CR rate was not associated with cumulative vemurafenib dose (Figure 1A; P = .73) or treatment duration (P = .76).

Survival and relapse after vemurafenib treatment

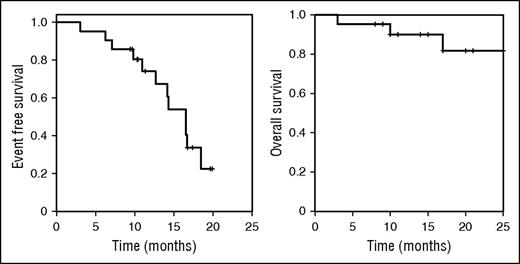

With a median observation time of 17 months, median event-free survival (EFS; start of vemurafenib treatment to retreatment or death) was 17 months (Figure 2). EFS was not influenced by cumulative administered dose of vemurafenib (P = .23; hazard ratio (HR), 0.90; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.8-1.1; effect size for HR per 10 g vemurafenib) or treatment duration (P = .31; HR, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.6-2.1; effect size for HR per 1 month). Median time to relapse as defined by deterioration of blood counts below remission thresholds was 14 months, and overall survival at 12 months was 88%. Three of 21 patients died (disease progression, n = 120 ; pneumonia in remission, n = 1; AML, n = 1). Achieving a CR after vemurafenib treatment was associated with better EFS (time from cessation of vemurafenib/response assessment to retreatment or death; P = .04; HR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9).

EFS and overall survival after vemurafenib treatment. EFS (time from start of vemurafenib to death or retreatment) and overall survival of patients receiving vemurafenib for HCL (n = 21). Median EFS from start of treatment was 17 months and median overall survival was not reached. Median time after cessation of vemurafenib treatment to retreatment or death was 14 months.

EFS and overall survival after vemurafenib treatment. EFS (time from start of vemurafenib to death or retreatment) and overall survival of patients receiving vemurafenib for HCL (n = 21). Median EFS from start of treatment was 17 months and median overall survival was not reached. Median time after cessation of vemurafenib treatment to retreatment or death was 14 months.

Nine patients (42%), including the 2 patients treated upfront, were re-treated at relapse (range, 4-17 months). Six patients were reexposed to vemurafenib and responded (Table 2). Two patients received a second course of low-dose vemurafenib, and 4 patients (Heidelberg 03 and 05, Cambridge, and Nice 01) received continuous treatment at either 240 mg once daily or 240 mg twice daily (14, 6, 25 and 9 months from restarting therapy, respectively). Kinetics of response resembled the initial treatment course (Figure 1).

Patient characteristics and follow-up of patients with HCL retreated after vemurafenib

| Patient . | Retreatment . | Vemurafenib dose . | Response . | Time to retreatment (mo) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heidelberg 01 | Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 | Blood count recovery | 14 |

| Heidelberg 03 | Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 continues retreatment | PR | 9 |

| Heidelberg 05 | R-Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 | Blood count recovery | 6 |

| Cambridge | Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 continues retreatment | PR | 25 |

| Innsbruck 02 | Vemurafenib | 1 × 240 | Blood count recovery | 11 |

| Nice 01 | Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 (5 mo) and 1 × 240 continuously | Blood count recovery | 14 |

| Heidelberg 02 | R-Pentostatin | CR | 12 | |

| Nice 02 | Cladribine | Blood count recovery | 4 | |

| Innsbruck 04 | Obinutuzumab | Ongoing treatment | 3 |

| Patient . | Retreatment . | Vemurafenib dose . | Response . | Time to retreatment (mo) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heidelberg 01 | Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 | Blood count recovery | 14 |

| Heidelberg 03 | Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 continues retreatment | PR | 9 |

| Heidelberg 05 | R-Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 | Blood count recovery | 6 |

| Cambridge | Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 continues retreatment | PR | 25 |

| Innsbruck 02 | Vemurafenib | 1 × 240 | Blood count recovery | 11 |

| Nice 01 | Vemurafenib | 2 × 240 (5 mo) and 1 × 240 continuously | Blood count recovery | 14 |

| Heidelberg 02 | R-Pentostatin | CR | 12 | |

| Nice 02 | Cladribine | Blood count recovery | 4 | |

| Innsbruck 04 | Obinutuzumab | Ongoing treatment | 3 |

R, rituximab.

Pharmacodynamic assessment of BRAF V600E targets

To understand the effect of vemurafenib on downstream BRAF V600E targets, we assessed expression of p-ERK and presence of BRAF V600E–positive cells by immunohistochemistry. Upon vemurafenib treatment, the hairy cell infiltration of the marrow decreased to meet response criteria (>50%, Figure 1B). Using Pax5/p-ERK double staining of trephine biopsy samples, we found complete abrogation of p-ERK in PAX5-positive cells at 240 mg (twice daily) of vemurafenib (Figure 1B). Cyclin D1 expression was undetectable in hairy cells after vemurafenib exposure, suggesting BRAF dependence (patient 01, day 6; patient 02, day 63; and patient 03, day 85).9,11

To gain a comprehensive understanding of cytokines involved in HCL, we performed cytokine arrays of serum samples before and upon vemurafenib treatment (supplemental Figure 2). Soluble CD25 (sCD25; interleukin-2 receptor) was downregulated upon vemurafenib treatment, and additional cytokines that decreased with treatment included insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type I and II, and B-cell-attracting chemokine 1 (supplemental Figure 2). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, CCL5/RANTES, epidermal growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor (supplemental Figure 2) increased upon BRAFi treatment. We repeatedly measured sCD25 serum levels in a subgroup of patients (n = 6). sCD25 levels decreased below the upper normal limit after a median of 36 days (Figure 1C). After cessation of vemurafenib, sCD25 levels rose, exhibiting individual progression dynamics (Figure 1C).

Side effects during vemurafenib treatment

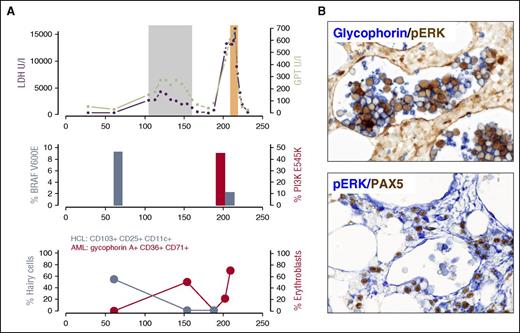

The side-effect profile of vemurafenib included arthralgia (n = 4), which resolved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or low-dose steroids, and mild reversible elevation of liver enzymes (n = 4). An 89-year-old patient developed acute on chronic renal failure during vemurafenib treatment. Phototoxicity (National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria grade ≤2, n = 4), keratoacanthomas (n = 3), squamous cell papilloma (n = 1), and squamous cell carcinomas (n = 1) occurred (Table 1). Except for 1 patient with keratoacanthoma who received 480 mg of vemurafenib twice daily, all patients with skin tumors received 240 mg twice daily. Progression of non–skin cancer has been reported during vemurafenib treatment,24,25 which was linked to RAS-mediated paradox ERK activation of wild-type BRAF in the context of vemurafenib. Patient 12 presented with pure red cell AML-M6b accelerated by vemurafenib treatment (Figure 3). While exposed to vemurafenib, the patient had 40% of erythroblasts (glycophorin A+, CD36+, CD71+, CD34−; supplemental Figure 3) in the peripheral blood (Figure 3). Lactate dehydrogenase levels and liver enzymes increased on vemurafenib, but after cessation of vemurafenib, both lactate dehydrogenase and transaminases returned to normal levels and erythroblasts disappeared from the peripheral blood (Figure 3). At 1.8 months after discontinuation of vemurafenib, the patient was diagnosed with AML-M6, with massive elevation of liver function tests. The diagnosis was confirmed by immunophenotyping (supplemental Figure 3) and bone marrow histology (Figure 3). Standard molecular workup revealed a translocation t(20;22)(q13.1;q13). Next-generation sequencing (454 and Ion Torrent Hotspot Panel v2) showed wild-type NRAS and KRAS, but we identified an activating PI3KCA mutation (E545K). We performed deep-sequencing (Ion Torrent, >16 000 reads) using trephine biopsy material taken 44 days before vemurafenib was administered, and could not detect the PI3KCA mutation (E545K) within the sensitivity of the assay used (>0.1%). Vemurafenib can cause paradoxical ERK activation in the context of wild-type BRAF and activated RAS.26 Because phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) has been demonstrated to activate RAS,27 we choose cell line models (MCF-7 and L363) with PI3KCA E545K mutation and exposed the cell lines to BRAFi in vitro. We demonstrated paradoxical ERK activation upon BRAFi treatment similar to a RAS mutant control cell line (NOMO-1). It was unfortunate that viable tissue from the time of vemurafenib treatment was not available for the patient, but immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong p-ERK expression in the glycophorin A+ intrasinusoidal erythroblasts in the trephine biopsy material at diagnosis of the AML-M6 (Figure 3).

AML-M6 evolution and vemurafenib treatment. (A) Upper image: during vemurafenib treatment (gray box) lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; purple) levels (maximum 4297 U/L, normal range <250 U/L) and transaminases (green) increased. LDH levels were above normal levels before vemurafenib was administered, but liver enzymes rose with vemurafenib. During vemurafenib treatment, fluorescence-activated cell sorting demonstrated 40% of erythroblasts (red: glycophorin A+, CD36+, CD71+, CD34−) in the peripheral blood. After stopping vemurafenib, the LDH levels and liver enzymes returned to normal and erythroblasts disappeared from the peripheral blood (upper and lower images), suggesting dependence on vemurafenib. At 1.8 months after the stop of vemurafenib treatment, erythroblasts with the above-mentioned immunophenotype were again found in the peripheral blood, accompanied by massively elevated liver enzymes and LDH levels exceeding 16 000 U/L. BRAF V600E allele frequency (steel blue, middle image) and hairy cells (CD25, CD103, CD11c; steel blue, lower image) were significantly reduced upon vemurafenib treatment, whereas AML with PI3KCA mutation (E545K) emerged in the AML clone (middle image). We performed deep sequencing (Ion Torrent, >16 000 reads) on a trephine biopsy sample taken 44 days before vemurafenib was administered. The PI3KCA mutation E545K could not be confirmed within the sensitivity of the assay. (B) Immunohistochemistry revealed the strong positivity of p-ERK in glycophorin A+ intrasinusoidal erythroblasts (bone marrow biopsy) as a sign of ERK activation. Original magnification ×40. Orange box indicates AML induction treatment. GPT, glutamate pyruvate transaminase.

AML-M6 evolution and vemurafenib treatment. (A) Upper image: during vemurafenib treatment (gray box) lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; purple) levels (maximum 4297 U/L, normal range <250 U/L) and transaminases (green) increased. LDH levels were above normal levels before vemurafenib was administered, but liver enzymes rose with vemurafenib. During vemurafenib treatment, fluorescence-activated cell sorting demonstrated 40% of erythroblasts (red: glycophorin A+, CD36+, CD71+, CD34−) in the peripheral blood. After stopping vemurafenib, the LDH levels and liver enzymes returned to normal and erythroblasts disappeared from the peripheral blood (upper and lower images), suggesting dependence on vemurafenib. At 1.8 months after the stop of vemurafenib treatment, erythroblasts with the above-mentioned immunophenotype were again found in the peripheral blood, accompanied by massively elevated liver enzymes and LDH levels exceeding 16 000 U/L. BRAF V600E allele frequency (steel blue, middle image) and hairy cells (CD25, CD103, CD11c; steel blue, lower image) were significantly reduced upon vemurafenib treatment, whereas AML with PI3KCA mutation (E545K) emerged in the AML clone (middle image). We performed deep sequencing (Ion Torrent, >16 000 reads) on a trephine biopsy sample taken 44 days before vemurafenib was administered. The PI3KCA mutation E545K could not be confirmed within the sensitivity of the assay. (B) Immunohistochemistry revealed the strong positivity of p-ERK in glycophorin A+ intrasinusoidal erythroblasts (bone marrow biopsy) as a sign of ERK activation. Original magnification ×40. Orange box indicates AML induction treatment. GPT, glutamate pyruvate transaminase.

PI3K mutations have not been associated with AML.28 We therefore analyzed 40 acute erythroid leukemias (37 erythroleukemia M6a and 3 pure erythroid leukemia M6b) and found no additional PI3K mutations, suggesting that these mutations are not recurrent at higher frequencies in AML-M6.

Discussion

We describe the outcome of vemurafenib treatment in 21 patients with HCL. Our findings indicate that a short course of BRAF inhibition with a low-dose of vemurafenib can effectively inhibit MEK/ERK signaling in vivo, reduce HCL load, and induce CRs in HCL patients. These data confirm the critical dependence on active BRAF signaling in HCL.

Despite rapid improvement of blood counts, CR was achieved in only 40% of patients, which is in line with the CR rates reported in the prospective phase 2 trials.17 Although mechanisms underlying disease persistence are currently unclear, our data suggest that insufficient dosing is unlikely to be the cause for heterogeneous response. Immunohistochemistry showed completely abrogated ERK activation, indicating on-target efficacy of low-dose vemurafenib. In line with these observations, sCD25 (sIL2R-α) levels were rapidly reduced with vemurafenib, including patients with persisting hairy cell infiltration. In melanoma, combination treatments of BRAFi and MEKi have been demonstrated to improve response rates and survival.29 Whether response rates can also be improved in HCL is currently being tested in clinical trials (eg, NCT02034110).

Although we observed no progressions on drug, the median time to retreatment after cessation of vemurafenib was 14 months. Residual cells appear to reenter proliferation and give rise to disease progression when treatment is stopped. To develop more effective treatment schedules for BRAF inhibition or combination treatment, it would be critical to understand why HCL cells persist in the presence of inhibited MEK/ERK signaling. Potential explanations include failure to execute cell death upon oncogene inhibition (eg, with vemurafenib).11 BRAF V600E has been shown to suppress the cell cycle regulator p27,30 which is recurrently mutated in HCL,31 suggesting that cell cycle control or oncogene-induced senescence might be alternative fail-safe mechanisms. Failure to clear disease could also be based on alternative survival pathways; for example, microenvironmental signals or B-cell receptor signaling.32

The vemurafenib schedule (960 mg twice daily) was derived from a phase 1 trial in melanoma and was based on the predefined incidence of dose-limiting toxicities. Concerns have been raised about whether dose-finding strategies based on dose-limiting toxicities as established for chemotherapy drugs can be adopted for targeted drugs.18,19 Two prospective studies have used the standard dose of vemurafenib (960 mg twice daily) and report response rates and relapse-free survival rates strikingly similar to those of the current study.17 In the prospective studies, dose reduction was necessary in >50% of patients (Italian trial, 14/26; US trial, 17/28) and no difference in outcome of patients receiving the full or the reduced dose could be demonstrated.

Long-term treatment of cancer with BRAFi is challenged by secondary resistance formation33-35 and development of secondary tumors based on paradoxical ERK activation in cells with wild-type BRAF. Skin cancers have been reported at frequencies of 15% to 30% in BRAF-mutant melanoma patients receiving BRAFi,36 and we observed a comparable frequency (24%). Low doses may therefore cause on-target, but also comparable, rates of side effects. In tumors and normal cells with wild-type RAF, BRAFi paradoxically stimulates ERK signaling in a RAS-dependent manner.26,37 In addition, case reports describe patients who experienced progression of preexisting RAS-mutated (chronic myelomonocytic leukemia) or RAS pathway–driven malignancies (eg, pancreatic cancer38 ) during BRAFi treatment.25,38 BRAFi-mediated paradoxical ERK activation was shown to be B-cell-receptor dependent in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells.24

We provide further in vivo insight on the risk of BRAFi-driven malignancies and report 1 patient who developed an AML-M6b (subtype pure red cell AML) during vemurafenib treatment. In line with the concept of enhanced paradoxical ERK activation in the context of activated RAS, we identified a PI3K (E545K) mutation in the emerging AML clone, which is known to activate RAS.27 Although we cannot directly demonstrate p-ERK activation in erythroblasts during vemurafenib treatment, our results show ERK activation in AML cells. The biphasic course and the regression after vemurafenib cessation suggest that vemurafenib may have contributed to AML-M6 development. These data support the use of MEKi also in HCL, in order to reduce the risk of paradoxical ERK activation.39 The majority of reports on BRAFi-induced secondary malignancies describe preexisting malignant or premalignant clones, which experience accelerated clonal expansion upon BRAFi exposure.25,38 Although we were not able to detect an AML clone before vemurafenib treatment based on very deep sequencing of the PI3K mutation, we cannot prove the preexistence of premalignant precursors. With 5 prior lines of chemotherapy, a contribution of DNA-damaging agents to the formation of AML cannot be excluded.

We report stable long-term remissions on low-dose vemurafenib, but continuous treatment involves the risk of resistance formation and secondary malignancies. This risk might be reduced with altered on-off dosing schedules Experimental models of BRAF inhibition have shown a reduction in resistance formation when BRAFi are applied in on-off schedules.40

Despite the retrospective nature and the number of patients studied, our analysis provides starting points for the reevaluation of traditional approaches to dose finding for targeted cancer drugs. Although not a clinical trial, the individual dosing regimens allowed us to systematically assess the impact of dosing on clinical and pharmacodynamic end points. Major innovations in targeted treatment41,42 have stemmed from clinical observations outside of trials. The results of the current work support detailed dose-finding studies assessing molecular-target inhibition and side-effect profile when using targeted anticancer drugs. The data also suggest that optimal dosing schedules for vemurafenib may need to be reassessed in clinical trials, which could have major pharmacoeconomic implications.

Future trials exploring precision medicine should accommodate flexible end points integrating biomarker assessment of on-target effects together with traditional response assessment.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank T. Uhrig for technical assistance with immunohistochemical stainings, and B. Falini and E. Tiacci (Institute of Hematology, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy) for the double immunohistochemical staining for glycophorin and PAX5 and the review of bone marrow slides.

This work was supported by a Heidelberg Research Centre for Molecular Medicine grant (S.D.); the Deutsche Krebshilfe (Mildred Scheel Professorship [T.Z.]); the Hairy Cell Foundation; Molecular Medicine Partnership Unit (European Molecular Biology Laboratory and University Hospital Heidelberg); and a Leicester Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre grant (C325/A15575 Cancer Research UK/Department of Health, United Kingdom).

Authorship

Contribution: S.D. and T.Z. designed and performed the research, provided the samples, and wrote the paper; A.P., G.A.F., J.H., A.J., T.W., T.E., T.B., R.Z., W.W., C.v.K., A.D.H., and M. Seiffert performed the research and edited the paper; E.E., V.E., M.A., and M. Steurer performed the research and wrote the paper; and A.D.H., C.-M.W., F.P., M. Hermann, M. Herold, C.D., T.H., M. Hallek, X.L., M.J.S.D., and A.G. provided the samples and edited the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thorsten Zenz, Department of Translational Oncology, National Center for Tumor Diseases and German Cancer Research Center, Im Neuenheimer Feld 460, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; e-mail: thorsten.zenz@nct-heidelberg.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal