To the editor:

Congenital neutropenia (CN) and cyclic neutropenia (CyN) are rare genetic disorders of hematopoiesis predominantly caused by ELANE mutations.1-3 Due to overlaps in their genetic profiles, CyN can be distinguished from CN by cycling neutrophil counts, usually at 21-day intervals, in the former. In contrast to CN, CyN is also characterized by cycling of platelets, monocytes, and reticulocytes.4,5 Infectious episodes are usually less severe in patients with CyN vs CN. Although CSF3R mutations are frequent in patients with CN and these patients are at increased risk of leukemic transformation, CSF3R mutations and transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have not been reported to date in patients with CyN.6-11

This report describes a 17-year-old female with CyN who developed AML (French-American-British classification M2). She was first diagnosed with severe neutropenia at age 4 weeks while experiencing Pseudomonas septicemia; at that time, serial blood counts were not collected. Treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), at a dose of 5.7 μg/kg per day, was initiated at age 2 years. The amount of G-CSF administered was not adjusted for increasing body weight, resulting in a dose of 1.7 μg/kg per day at age 13 years. After a liver abscess at age 14 years, she was referred to our center. She presented with large variations in absolute neutrophil count (ANC), suggesting a cyclic pattern of ANC. Because her median ANC was deemed insufficient, her G-CSF dose was increased to 7.5 μg/kg per day. This relatively high dosage is still in the range of G-CSF dosages required for CyN patients (0.5-10.5 μg/kg per day); however, it is higher than the median dose (2.6 μg/kg per day) in CyN patients within our European branch of the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry (SCNIR) and might be associated with the risk of malignant development. Sequential neutrophil counts, determined at least 3 times per week for 6 weeks, over 2 time periods 4 months apart, confirmed a diagnosis of CyN (Figure 1A-B). Cycling platelet counts have been reported previously in patients with CyN, but not CN.4,5 No cytogenetic aberrations were detected prior to a diagnosis of AML. BM at the time of AML showed 33% blasts, monosomy 7, and trisomy 21. The patient recently received a BM transplant from an HLA-matched unrelated donor and was released from the hospital after successful engraftment.

Patient characteristics associated with neutropenia. (A-B) Representative patterns of neutrophil (blue line) and platelet (orange line) cycling in the CyN-AML patient during G-CSF treatment. ANCs and platelet counts were plotted for 25 days (left) and for 35 days (right), accordingly. (C) Genetic characterization of double de novo ELANE mutations in the CyN-AML patient. The blue arrows above the Sanger sequencing traces indicate the positions of the mutations. Cloning of a genomic DNA fragment spanning ELANE c.697G<C and c.703delG showed that both mutations were present on the same allele. Two representative examples of sequenced clones are shown. Sequencing of ELANE exon 5 revealed no ELANE mutations in parental DNA isolated from peripheral blood MNCs. (D) Western blot analysis of ELANE protein expression in BM polymorphonuclear cells of the CyN-AML patient and healthy donors. β-actin was used as a loading control. The level of ELANE protein expression was lower in BM polymorphonuclear cells of the CyN-AML patient as compared with healthy donors. The blot shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. BM, bone marrow; MNC, mononuclear cell.

Patient characteristics associated with neutropenia. (A-B) Representative patterns of neutrophil (blue line) and platelet (orange line) cycling in the CyN-AML patient during G-CSF treatment. ANCs and platelet counts were plotted for 25 days (left) and for 35 days (right), accordingly. (C) Genetic characterization of double de novo ELANE mutations in the CyN-AML patient. The blue arrows above the Sanger sequencing traces indicate the positions of the mutations. Cloning of a genomic DNA fragment spanning ELANE c.697G<C and c.703delG showed that both mutations were present on the same allele. Two representative examples of sequenced clones are shown. Sequencing of ELANE exon 5 revealed no ELANE mutations in parental DNA isolated from peripheral blood MNCs. (D) Western blot analysis of ELANE protein expression in BM polymorphonuclear cells of the CyN-AML patient and healthy donors. β-actin was used as a loading control. The level of ELANE protein expression was lower in BM polymorphonuclear cells of the CyN-AML patient as compared with healthy donors. The blot shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. BM, bone marrow; MNC, mononuclear cell.

Interestingly, this CyN-AML patient was found to harbor 2 ELANE mutations, p.Ala233Pro and p.Val235TrpfsX (NP_001963.1), both located on 1 allele (Figure 1C). The ELANE fragment spanning c.697G<C and c.703delG was cloned from genomic DNA isolated from this patient’s peripheral blood MNCs. Sequencing of 20 individual bacterial clones showed that all clones carried both ELANE mutations (Figure 1C). Sequencing of DNA isolated from peripheral blood MNCs of both parents revealed no ELANE mutations (Figure 1C). Moreover, neither parent has shown signs of neutropenia or episodes of bacterial infections. Interestingly, the levels of expression of ELANE protein were much lower in BM polymorphonuclear cells of this CyN-AML patient as compared with healthy controls (Figure 1D).

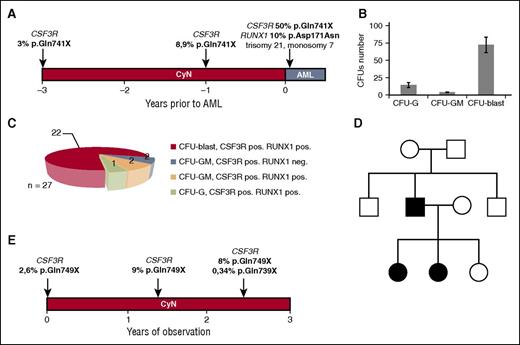

CN is a preleukemic condition, with >20% of patients developing leukemia after 20 years.6,8-11 Approximately 80% of CN patients who develop AML are heterozygous for CSF3R mutations, suggesting the involvement of these mutations in leukemogenesis.6-12 To date, CSF3R mutations have never been reported in patients with CyN.7 Deep sequencing of DNA from this patient’s BM MNCs obtained 3 years before the diagnosis of AML revealed a clone with the acquired CSF3R mutation p.Gln741X at a 3% allele frequency (Figure 2A). Two years later, or 1 year before AML diagnosis, the CSF3R mutant allele frequency in this patient’s BM MNCs was 8%. At the time of AML diagnosis, all CSF3R-expressing BM MNCs (predominantly leukemic blasts) were positive for the p.Gln741X mutation (Figure 2A). Because cooperative RUNX1 and CSF3R mutations are present in >65% of CN-AML/MDS patients,12 we tested the patient’s BM MNCs, obtained at the time of leukemia development, for RUNX1 mutations, finding that the RUNX1 mutation p.Asp171Asn was present at an allele frequency of 10%.

Acquired CSF3R mutations in the CyN-AML and CyN patients described in this study. (A) The time course and frequency of CSF3R mutations in the CyN-AML patient, as determined by deep sequencing, for 3 years prior to the development of overt AML. Mutant allele frequency and mutation position are indicated above each time point. All mutations were considered heterozygous, and the number of cells with a CSF3R mutation was estimated to be twice the frequency of the mutant allele. The RUNX1 mutation p.Asp171Asn was present only after development of MDS. (B) CFU-blast colonies were predominant after incubation for 14 days with a cytokine cocktail, consisting of 10 ng/mL rhG-CSF, 10 ng/mL rhGM-CSF, 10 ng/mL rhIL-3, 10 ng/mL rhSCF, and 1 U/mL rhEPO. (C) Diagram of the distribution of CSF3R and RUNX1 mutations in different CFU colonies isolated from a sample from the CyN-AML patient taken after the development of AML. (D) Autosomal dominant inheritance of the ELANE mutation p.Val190_Phe199del in a CyN patient with an acquired CSF3R mutation. The ELANE mutation was inherited by 2 daughters from their affected father, who also showed cyclic hematopoiesis. (E) Time course and frequency of CSF3R mutations in a patient with familial CyN, as determined by deep sequencing, starting from the date of the first mutation analysis. Mutant allele frequency and mutation position are indicated above each time point. All mutations were considered heterozygous, and the number of cells with CSF3R mutations was estimated to be twice the frequency of the mutant allele. CFU, colony-forming unit; EPO, erythropoietin; G, granulocyte; GM, granulocyte-macrophage; IL, interleukin; rh, recombinant human.

Acquired CSF3R mutations in the CyN-AML and CyN patients described in this study. (A) The time course and frequency of CSF3R mutations in the CyN-AML patient, as determined by deep sequencing, for 3 years prior to the development of overt AML. Mutant allele frequency and mutation position are indicated above each time point. All mutations were considered heterozygous, and the number of cells with a CSF3R mutation was estimated to be twice the frequency of the mutant allele. The RUNX1 mutation p.Asp171Asn was present only after development of MDS. (B) CFU-blast colonies were predominant after incubation for 14 days with a cytokine cocktail, consisting of 10 ng/mL rhG-CSF, 10 ng/mL rhGM-CSF, 10 ng/mL rhIL-3, 10 ng/mL rhSCF, and 1 U/mL rhEPO. (C) Diagram of the distribution of CSF3R and RUNX1 mutations in different CFU colonies isolated from a sample from the CyN-AML patient taken after the development of AML. (D) Autosomal dominant inheritance of the ELANE mutation p.Val190_Phe199del in a CyN patient with an acquired CSF3R mutation. The ELANE mutation was inherited by 2 daughters from their affected father, who also showed cyclic hematopoiesis. (E) Time course and frequency of CSF3R mutations in a patient with familial CyN, as determined by deep sequencing, starting from the date of the first mutation analysis. Mutant allele frequency and mutation position are indicated above each time point. All mutations were considered heterozygous, and the number of cells with CSF3R mutations was estimated to be twice the frequency of the mutant allele. CFU, colony-forming unit; EPO, erythropoietin; G, granulocyte; GM, granulocyte-macrophage; IL, interleukin; rh, recombinant human.

A CFU assay was performed to determine the stage of myeloid differentiation at which CSF3R mutations occurred in this CyN-AML patient. Of the BM MNCs isolated at the time of overt AML, 80% were abnormal CFU-blasts, 16% were CFU-G colonies, and 4% were CFU-GM colonies (Figure 2B). All 22 CFU-blast colonies sequenced were positive for the CSF3R p.Gln741X and RUNX1 p.Asp171Asn mutations (Figure 2C).

To determine whether other CyN patients harbor CSF3R mutations, we performed deep sequencing of CSF3R in 18 additional CyN patients, finding that cell clones from 1 patient aged 15.4 years had an acquired CSF3R mutation. This patient and her sister had inherited CyN from their father, with all 3 harboring an ELANE p.Val190_Phe199del (NP_001963.1) mutation and presenting with cycling hematopoiesis (Figure 2D). Time-course analysis of the acquisition of CSF3R mutations in this patient showed that 2.6% of the CSF3R alleles in BM MNCs obtained at age 13 years possessed the p.Gln749X mutation, with the mutant allele frequency increasing to 9% and 8% after an additional 1.5 and 2.4 years, respectively. At the last time point, an additional minor mutant clone was identified, with the CSF3R mutation p.Gln739X and an allele frequency of 0.34% (Figure 2E). This CyN patient has no signs of AML or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Taken together, these findings suggest that CyN patients with familial type inheritance and typical CyN-associated ELANE mutations also may acquire CSF3R mutations.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of acquired CSF3R mutations in CyN patients, with 1 patient subsequently developing AML. The diagnosis of CyN in the first patient was verified through 2 independent courses of neutrophil counts, with this patient also showing cycling of platelets and monocytes. The second patient, with inherited CyN, was positive for an acquired CSF3R mutation, but has no signs of AML or MDS. Long-term data of the SCNIR have shown no risks of acquisition of CSF3R mutations and of myeloid transformation in patients with CyN to date.7,8 The risk of malignant transformation in patients who acquired CSF3R mutations, however, has been documented in patients with CN. In our recent analyses using the same deep-sequencing technology as has been used for the 2 CyN patients, we searched for the presence of CSF3R mutations in 45 patients with ELANE-positive CN. Sixteen of the 45 patients (35.5%) harbored CSF3R mutations; 8 of them (18%) had developed AML. The incidence of CSF3R mutations in CN suggests that clonal populations with CSF3R mutations can expand in CN patients and never evolve into malignant hematopoiesis. This finding may have parallels with recent studies showing that clonal populations with mutations in AML-associated genes are common in older adults and much more common than the frequency of AML.13

Because we have identified only 2 CyN patients with CSF3R mutations, with 1 developing AML and the other without malignant transformation to date, the clinical importance of annual CSF3R mutational analysis to identify CyN patients at high risk of developing leukemia remains unanswered. The CyN-AML patient we identified differs from other patients with CyN in that she required doses of G-CSF that were high (but still within the treatment range of CyN patients in our SCNIR). Genotype–phenotype correlations indicate that the same ELANE mutation can result in either CN or CyN, depending on the genetic background.10,14 The second CyN patient described here had typical familial CyN, inheriting from her father the ELANE p.Val190_Phe199del mutation, which is common in both CyN and CN. She responded to a very low dose (1.5 μg/kg per day) G-CSF therapy. Although CN and CyN are closely related disorders with overlapping molecular and clinical phenotypes,2 platelet cycling was not reported in CN patients in the SCNIR,7 suggesting that both patients described in this report had classical CyN, not masked CN. Haurie et al reported that in CyN, the available evidence indicates a broad involvement of the entire hematopoietic system, because cycling is typically observed in more than 1 of the mature hematopoietic cell types.15 This characterization is in agreement with our definition of CyN. In our opinion, the clinician has to decide on the clinical and molecular data available to classify a patient as CyN or CN, and prognostic counseling is based on this clinical classification.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the physicians of the SCNIR for providing patient material and the study subjects for their cooperation.

This work was supported by the Madeleine-Schickedanz Kinderkrebsstiftung, the German Jose Carreras Leukemia Foundation, the Excellence Initiative of Tuebingen University, the Fortuene program of Tuebingen University, E-Rare (European Research Programmes on Rare Diseases), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (German Network on Congenital Bone Marrow Failure Syndromes), and the Volkswagen Foundation (Niedersachsenprofessur).

Contribution: M.K. performed the main experiments; C.Z. and S.M.-H. provided the patient material and clinical data; E.R. performed the Sanger sequencing and cloning; O.K. performed the CFU assays; M.U., S.K., and M.K. analyzed the deep-sequencing data of CSF3R; and J.S., K.W., C.Z., S.M.-H., and M.K. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Karl Welte, University Children’s Hospital, Hoppe-Seyler-Strasse 1, 72076 Tübingen, Germany; e-mail: karl.welte@med.uni-tuebingen.de.

References

Author notes

M.K. and S.M.-H. contributed equally to this study.

K.W. and C.Z. contributed equally to this study.