To the editor:

Recent reports on the genetic landscape of the plasma cell malignancy, multiple myeloma (MM), have revealed potential therapeutic targets such as activating mutations in BRAF kinase in subsets of patients.1-4 However, assuming suitable targeted therapies become available, clonal evolution and widespread intraclonal heterogeneity in MM will pose a challenge to their routine clinical use.2,3

We were the first to report on the successful use of mutation-specific targeted therapy in a patient with MM (refractory to all available therapy at that time, presenting with multiple extramedullary lesions and a clonal BRAFV600E mutation) whose disease responded to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib.1 In contrast to BRAF-driven malignant melanoma, there are no reports on the follow-up of such a treatment strategy in MM. The patient, a 63-year-old woman, remained in stable remission on low-dose intermittent therapy with vemurafenib (240 mg by mouth twice daily, days 1-14/28) for 9 months (Figure 1A-B). Intermittent dosing was chosen because it has been described as a potential strategy to prevent or delay development of vemurafenib resistance.5

The clinical course and management of a patient with BRAFV600E-mutant MM developing resistance to treatment with vemurafenib. Schematic dynamic overview of the myeloma cell populations, according to their mutational status, in relation to treatment with vemurafenib (Vem), bortezomib and dexamethasone (BTZ/DEX), and the combination regimen (A). The monoclonal proteins were monitored over time by serum and urine electrophoresis, respectively (B). Representative MRI images of intramedullary BRAFV600E-mutant lesions of the proximal right tibia (C), initially responding to vemurafenib (NRASWT, month 5) acquiring a de novo NRASG12A mutation associated with resistance to vemurafenib (month 15), responding to BTZ/DEX as well as to the combination Vem-BTZ/DEX (month 25). (D) Immunohistochemistry denotes proliferation (by MIB1 expression) and activation status of ERK signaling (by phosphorylation of ERK [pERK]). Serial biopsies were taken from BRAFV600E-mutant extramedullary lesions with a concomitant NRASG13R mutation (top row) or a NRASWT background (bottom row) at the time of relapse while on intermittent low-dose vemurafenib (month 10), on full-dose vemurafenib (month 15), and on bortezomib/dexamethasone (month 20). Although full-dose vemurafenib abrogates proliferation and ERK activation in the NRASWT tumor, no changes are seen in NRASG13R. In contrast, the opposite effects are seen on treatment with bortezomib/dexamethasone, confirming the contradictory responses seen to each regimen. wt, wild type.

The clinical course and management of a patient with BRAFV600E-mutant MM developing resistance to treatment with vemurafenib. Schematic dynamic overview of the myeloma cell populations, according to their mutational status, in relation to treatment with vemurafenib (Vem), bortezomib and dexamethasone (BTZ/DEX), and the combination regimen (A). The monoclonal proteins were monitored over time by serum and urine electrophoresis, respectively (B). Representative MRI images of intramedullary BRAFV600E-mutant lesions of the proximal right tibia (C), initially responding to vemurafenib (NRASWT, month 5) acquiring a de novo NRASG12A mutation associated with resistance to vemurafenib (month 15), responding to BTZ/DEX as well as to the combination Vem-BTZ/DEX (month 25). (D) Immunohistochemistry denotes proliferation (by MIB1 expression) and activation status of ERK signaling (by phosphorylation of ERK [pERK]). Serial biopsies were taken from BRAFV600E-mutant extramedullary lesions with a concomitant NRASG13R mutation (top row) or a NRASWT background (bottom row) at the time of relapse while on intermittent low-dose vemurafenib (month 10), on full-dose vemurafenib (month 15), and on bortezomib/dexamethasone (month 20). Although full-dose vemurafenib abrogates proliferation and ERK activation in the NRASWT tumor, no changes are seen in NRASG13R. In contrast, the opposite effects are seen on treatment with bortezomib/dexamethasone, confirming the contradictory responses seen to each regimen. wt, wild type.

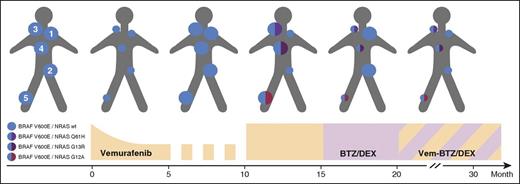

In month 10, biochemical disease relapse was accompanied by the growth of intra- and extramedullary lesions (Figure 1B-D). Vemurafenib was increased to the recommended standard dosing of 960 mg twice daily on a continuous schedule. At the same time, 5 reference lesions were biopsied (Figure 2) and examined by immunohistochemistry and targeted resequencing using Ion Torrent semiconductor-based technology (supplemental Methods, see supplemental Data available on the Blood Web site for details). Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at month 15 revealed a mixed response with a dramatic shrinkage of 2 lesions and accelerated growth of the others (Figure 1C). Although all 5 reference lesions biopsied in month 10 still harbored a BRAFV600E mutation in all MM cells, an additional monoallelic NRAS mutation was detectable in each of the 3 lesions resistant to the full dose of vemurafenib (Figure 2). Of note, each lesion harbored a unique, independent, yet clonal NRAS mutation (NRASG13R, NRASG12A, and NRASQ61H, respectively; supplemental Table 1). Importantly, retrospective analysis of baseline biopsies of 2 lesions confirmed the de novo occurrence of the NRAS mutation (Figure 2 lesion 4). Vemurafenib was stopped immediately, as BRAF inhibitors are known to paradoxically activate downstream signaling in RAS-mutated cells, a fact that we also observed by assessing activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1D). The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib has been shown to abrogate activation of signaling events downstream of the RAS/Raf cascade.6 Therefore, a proteasome inhibitor-based therapy (bortezomib/dexamethasone) was started at month 15. The NRAS-mutated lesions immediately decreased in size and, biochemically, a very-good-partial remission was achieved. However, the BRAFV600E/RASWT lesions, where the mutation status had been reconfirmed (supplemental Table 1), rapidly grew back by month 20 (Figure 1A-B), in line with a reactivation of the signaling downstream of the BRAF kinase while this appeared to be successfully suppressed by bortezomib in BRAFV600E/RASMUT lesions (Figure 1D).

Schematic overview of the representative myeloma lesions in the course of treatment. The 5 representative lesions were located at the left shoulder above the acromial bone (lesion 1), the left iliac bone (2), the right clavicle (3), adjacent to the sternal bone (4), and the right proximal tibia (5). Lesions 1, 3, and 5 were extramedullary tumors; lesions 2 and 4 were intramedullary computed tomography-guided biopsies. Bullet sizes depict growth and regression, respectively.

Schematic overview of the representative myeloma lesions in the course of treatment. The 5 representative lesions were located at the left shoulder above the acromial bone (lesion 1), the left iliac bone (2), the right clavicle (3), adjacent to the sternal bone (4), and the right proximal tibia (5). Lesions 1, 3, and 5 were extramedullary tumors; lesions 2 and 4 were intramedullary computed tomography-guided biopsies. Bullet sizes depict growth and regression, respectively.

This provided the rationale to combine vemurafenib-mediated BRAF inhibition with proteasome inhibition. The patient achieved durable biochemical disease stabilization with some lesions even shrinking in size when measured on cross-sectional imaging, which was ongoing at month 30.

This case provides first proof of 2 principles:

NRAS mutations seem to confer resistance to vemurafenib in BRAF-mutated MM, which can be overcome by proteasome inhibition, and

Spatially divergent clonal evolution triggered by therapy occurs in this hematologic malignancy as has been described in solid tumors.

Our observation that MM is a spatially heterogeneous disease highlights the inherent limitations of basing treatment decisions on the findings derived from a single bone marrow biopsy, irrespective of the growth pattern of the individual patient’s disease. This becomes especially apparent when applying targeted therapies based on predictive biomarkers. In this setting, consideration should be given to the assessment of such biomarkers in multiple lesions, ideally following imaging-guided biopsies. Moreover, the rational combining of compounds with complementary mechanisms of action has long been proposed as a treatment paradigm for MM and this principle is especially relevant when using targeted biomarker-based therapies as a means of overcoming or even preventing the development of resistance, the best studied example in melanoma being the combination of BRAF and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitors.5 To this end, the combination of BRAF and proteasome inhibitors in BRAF mutant MM should be further explored within clinical trials.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Contribution: M.S.R., J.X., and M.A. collected and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; and N.L., A.D.H., P.S., and H.G. provided patient care and expert advice.

Conflict-of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marc S. Raab, Department of Internal Medicine V, University Hospital Heidelberg, INF410, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; e-mail: marc.raab@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

![Figure 1. The clinical course and management of a patient with BRAFV600E-mutant MM developing resistance to treatment with vemurafenib. Schematic dynamic overview of the myeloma cell populations, according to their mutational status, in relation to treatment with vemurafenib (Vem), bortezomib and dexamethasone (BTZ/DEX), and the combination regimen (A). The monoclonal proteins were monitored over time by serum and urine electrophoresis, respectively (B). Representative MRI images of intramedullary BRAFV600E-mutant lesions of the proximal right tibia (C), initially responding to vemurafenib (NRASWT, month 5) acquiring a de novo NRASG12A mutation associated with resistance to vemurafenib (month 15), responding to BTZ/DEX as well as to the combination Vem-BTZ/DEX (month 25). (D) Immunohistochemistry denotes proliferation (by MIB1 expression) and activation status of ERK signaling (by phosphorylation of ERK [pERK]). Serial biopsies were taken from BRAFV600E-mutant extramedullary lesions with a concomitant NRASG13R mutation (top row) or a NRASWT background (bottom row) at the time of relapse while on intermittent low-dose vemurafenib (month 10), on full-dose vemurafenib (month 15), and on bortezomib/dexamethasone (month 20). Although full-dose vemurafenib abrogates proliferation and ERK activation in the NRASWT tumor, no changes are seen in NRASG13R. In contrast, the opposite effects are seen on treatment with bortezomib/dexamethasone, confirming the contradictory responses seen to each regimen. wt, wild type.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/127/17/10.1182_blood-2015-12-686782/4/m_2155f1.jpeg?Expires=1769308063&Signature=bUuZBFEOYg0i-Pso-hKylN28fjhrb0BFGZlyzKYr96c8x5g6~s5USnr4iV9WPR4Cf9h8TtmBIB9kLsNvyvm0MJwWoqnL4loMZHxX6~BwPYhzOrI-CFm9Xu059eKvZJ~nWSA~SmuvqKxQ7Xmapvah31jXyfTJIslfIIBSpSE-IERipfnUbH50nMMspubfXlJD3OUORrsgkWqDVXJHeqBVL87~33NBs0qBvcdHU0gMsB7EidpgkhqJSooeHM9tdJveHLCItjp7ZGwd31ICRRlO9-ugeVyc-bLG~yJESgUcMRSCpYST6n~TbGZJl7Sp1hzHwqwHegnHMwIw8jgaikYWEg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal