Key Points

TSCM lymphocytes are preferentially generated from naive precursors in vivo early after haploidentical HSCT.

TSCM represent relevant novel players in the diversification of immunological memory after haploidentical HSCT.

Abstract

Memory stem T cells (TSCM) have been proposed as key determinants of immunologic memory. However, their exact contribution to a mounting immune response, as well as the mechanisms and timing of their in vivo generation, are poorly understood. We longitudinally tracked TSCM dynamics in patients undergoing haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), thereby providing novel hints on the contribution of this subset to posttransplant immune reconstitution in humans. We found that donor-derived TSCM are highly enriched early after HSCT. We showed at the antigen-specific and clonal level that TSCM lymphocytes can differentiate directly from naive precursors infused within the graft and that the extent of TSCM generation might correlate with interleukin 7 serum levels. In vivo fate mapping through T-cell receptor sequencing allowed defining the in vivo differentiation landscapes of human naive T cells, supporting the notion that progenies of single naive cells embrace disparate fates in vivo and highlighting TSCM as relevant novel players in the diversification of immunological memory after allogeneic HSCT.

Introduction

Upon antigen recognition, naive T cells (TN) undergo extensive functional and phenotypic changes that drive their differentiation into effectors, which are committed to rapidly clearing the pathogen, and memory cells, which are able to survive long term, to ensure recall responses in case of pathogen recurrence.1 The memory compartment is multifaceted and encompasses multiple T-cell subsets with divergent properties.2 In addition to central memory cells (TCM) and effector memory cells (TEM),3 the spectrum of immunological memory has been recently extended with the identification of memory stem T cells (TSCM).4,5 Human TSCM lymphocytes express CD45RA, CCR7, and CD62L TN, but, different from TN and similar to other memory subsets, they are characterized by CD95 expression. Gene expression profiling, corroborated by in vitro and in vivo experimental results, posits TSCM upstream from TCM and TEM in T-cell ontogeny.4,5 However, whether TSCM represent a stable subset reproducibly generated on TN priming, and what the relationships of TSCM with the other memory subsets are, are still controversial issues. Furthermore, how human TSCM are formed in vivo, what the instructive signals guiding their formation and/or expansion are, and when they emerge during the immune response have not yet been elucidated.

The contribution of different memory T-cell subsets (although not TSCM) to the generation of effective primary and secondary immune responses has been elegantly studied at the single-cell level in murine models.6-10 In humans, however, this pursuit has been limited by ethical and technical constraints. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) provides a unique setting to longitudinally study the dynamics of discrete T-cell populations upon transfer directly in humans. During allogeneic T-replete HSCT, the recipient receives a myeloablative and lymphodepleting conditioning that abates the host hematopoietic compartment, followed by the infusion of a graft containing not only hematopoietic stem cells but also mature T cells from an allogeneic donor.11 The conditioning regimen induces systemic inflammation, thereby creating a milieu in which infused donor-derived lymphocytes are exposed to a high (allo)antigenic load. Therefore, close longitudinal sampling of peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) of patients after HSCT may allow tracking primary and/or secondary T-cell responses. We have previously shown that interleukin 7 (IL-7) and IL-15 are necessary to instruct the generation of human TSCM lymphocytes from naive precursors in vitro and that TSCM, which represent not more than 2% to 3% of circulating T cells in healthy subjects, are enriched early after HSCT, when these homeostatic cytokines are particularly abundant.5 Building on these observations, we investigated when and how TSCM emerge on transplant in vivo in the clinically relevant setting of haploidentical HSCT with posttransplant cyclophosphamide (pt-Cy).12,13 Understanding the complex dynamics of TSCM on allogeneic HSCT may ultimately inform on the role of this novel T-cell subset in posttransplant immune reconstitution (IR) and possibly provide novel hints on their physiological role.

Methods

Patients, procedures, and biological samples

Twenty consecutive adult patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies treated with myeloablative haploidentical HSCT in our Hematology Unit at San Raffaele Scientific Institute were studied. Patients received treosulfan-based myeloablative conditioning followed by an unmanipulated peripheral blood graft from an HLA-haploidentical related donor. Postgrafting graft-vs-host-disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of pt-Cy, 50 mg/kg per day, on days 3 and 4, followed by mycophenolate mofetil (15 mg/kg 3 times a day) for 30 days and sirolimus (target level, 8-15 ng/mL) for 3 months (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site). PB and BM samples of donors, patients, and healthy subjects were collected after written informed consent was approved by the San Raffaele Institutional Ethical Committee.

Multiparametric flow cytometry

Mononuclear cells (peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PBMCs) were isolated from PB and BM by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient separation (Lymphoprep; Fresenius) and were immediately used for subsequent analyses. All phenotypic and functional analyses were performed on freshly isolated samples. Eleven-color immunophenotypic analysis was performed using a LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Each acquisition was calibrated using Rainbow Calibration Particles (Spherotech) to correct for day-to-day variation. For intracellular staining, cells were stained with appropriate surface antibodies, washed, and then fixed and permeabilized with FOXP3 Fix/Perm Buffer Set (Biolegend) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were processed using FlowJo version 9.7.5 (TreeStar). T-cell subsets were defined according to the expression of CD45RA, CD62L, and CD95 as follows: TN: CD45RA+CD62L+CD95−; TSCM: CD45RA+CD62L+CD95−; TCM: CD45RA−CD62L+; TEM: CD45RA−CD62L−; and TEMRA: CD45RA+CD62L−. The supplemental Material provides detailed information on absolute quantifications, antibodies, fluorochromes, fluorescence-activated cell sorting, and gating strategy.

Aldefluor assay to determine aldehyde dehydrogenase activity

Aldefluor kit (Stem Cell Technologies) was used, following the manufacturer’s instructions, to identify cell populations with high aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzymatic activity. Briefly, PBMCs from leukapheresis or from PB were incubated with Aldefluor substrate for 30 minutes at 37°C, with and without diethylaminobenzaldehyde, and then stained for surface markers. Aldefluor was detected in the green fluorescence channel, and samples treated with diethylaminobenzaldehyde were used as controls to set the gates defining the ALDH+ region.

Quantification of serum cytokines

IL-7 and IL-15 serum concentrations were quantified by Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine 4-plex array (Bio-Rad). Samples were analyzed in duplicate. For each studied cytokine, a high-sensitivity standard curve was prepared by serial dilutions of recombinant proteins. Data were analyzed using Bio-Plex Manager version 6.1 (Bio-Rad).

T-cell receptor B CDR3 region sequencing and analysis

T-cell receptor β (TCRβ) chain hypervariable complementarity-determining region 3 (TCRB CDR3) was amplified and sequenced from DNA extracted from T-cell subsets (TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM/EFF) fluorescence-activated cell sorter(FACS)-purified (purity > 95%) from leukapheresis and from PB harvested 30 days post-HSCT from 3 consecutive patients using the ImmunoSEQ platform at Adaptive Biotechnologies.14 TCRB CDR3 region was defined as established by the International ImMunoGeneTics collaboration.15 Sequences that did not match CDR3 sequences were removed from the analysis. Rearranged CDR3 sequences were classified as nonproductive if they included insertions or deletions resulting in frameshifts or premature stop codons, and were excluded from subsequent analyses, according to the ImmunoSEQ validated algorithm. The average numbers of total productive nucleotide sequences retrieved were the following: leukapheresis product (LP) samples: TN: 1 197 527, TSCM: 1 140 816, TCM: 2 259 613, and TEM/EFF: 1 416 086; and day 30 samples: TN: 1 421 741, TSCM: 1 157 884, TCM: 1 288 319, and TEM/EFF: 1 788 812. Unique CDR3 sequences were identified and compared using R version 3.0.0. For T-cell subsets harvested 30 days post-HSCT, only CDR3 TCRB sequences whose reads were higher than 10 were considered for all LP samples and for the qualitative analyses of day 30 samples (to avoid inclusion of reading errors). No filters were applied to day 30 samples for quantitative analyses to ensure the inclusion of all substantial count reductions, indicative of clone contraction after infusion. TCRB sequence counts and T-cell subsets were clustered using Spearman correlation and average linkage; heat maps were drawn using gplots R package. Circos plots were performed as previously described.16

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). Data are shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise specified. Data were analyzed with paired t test when comparing the same subset between different points or with unpaired t test or standard analysis of variance when comparing across 2 or more different subsets. For all comparisons, 2-sided P values were used, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. For linear regression analyses, the best-fit values of the slopes were reported along with goodness-of-fit value (r2), P value of the slope (F test), and 95% confidence band. Significance of the slopes was independently verified using R.

Results

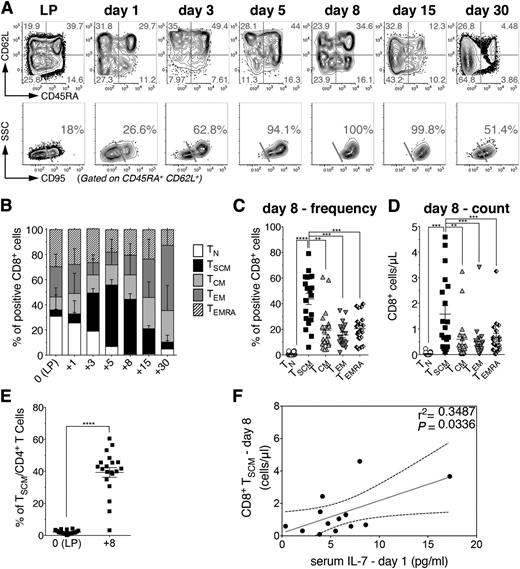

Donor-derived TSCM are selectively enriched early after haploidentical HSCT

To understand the dynamics and fate of human naive and memory T lymphocytes on HSCT, donor-derived T-cell subsets were longitudinally tracked within the first month after infusion into 20 consecutive high-risk hematological patients undergoing haploidentical myeloablative T-replete HSCT with pt-Cy. Patient and donor characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table 1. This HSCT platform (supplemental Figure 1A) allows tracking of CD3+ T cells even in the first 2 weeks post-HSCT, a possibility precluded in transplants exploiting antithymocyte globulins as an in vivo T-cell-depleting agent (supplemental Figure 1B). First, to rule out the possible contribution of residual host-derived lymphocytes to circulating cells, we analyzed peripheral T-cell chimerism in 4 patient-donor couples mismatched for HLA-A*0201. In both CD4+ and CD8+ compartments, host-derived T cells accounted for less than 30% of cells at day 1 after infusion and then decreased to less than 10% at day 5, disappearing by day 15 post-HSCT (supplemental Figure 2). Therefore, donor-derived T cells dominated even at the earliest points post-HSCT. On infusion and administration of pt-Cy, circulating TN gradually contracted, and by day 8 post-HSCT, the vast majority of circulating T lymphocytes were characterized by a memory phenotype (Figure 1A-B), indicating either a preferential sensitivity of TN to Cy or a massive differentiation of TN into memory/effector cells in the first week after transplant. Strikingly, at day 8 post-HSCT, CD8+ TSCM became the most represented circulating subset, in terms of both frequency and absolute counts (Figure 1C-D). Their frequency at day 8 was significantly higher than that within the infused graft (Figure 1D). CD4+ T-cell subpopulations displayed superimposable dynamics (supplemental Figure 3). In line with TSCM phenotypic characterization previously reported,4,5 CD8+ and CD4+ TSCM at day 8 post HSCT homogeneously expressed CCR7, CXCR4, CD27, and CD28 (supplemental Figure 4). Notably, serum concentration of IL-7 at day 1 appeared to correlate with the number of circulating CD8+ and CD4+ TSCM lymphocytes measured at day 8 (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 3), but not with TCM or TEM (supplemental Figure 5). At later points, TCM, TEM, and effectors prevailed, whereas CD8+ and CD4+ TN reappeared at day 30 post-HSCT (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 3). These results prompted us to unveil the origin of those TSCM lymphocytes highly represented at day 8 post-HSCT.

Donor-derived TSCM lymphocytes are selectively enriched early after haploidentical HSCT. (A) Flow cytometric plots of CD8+ T-cell phenotype from a representative patient (UPN#15) within the LP and at different points after HSCT, as labeled. Top row plots depict the expression of CD45RA and CD62L, which allows the identification of TCM (CD45RA−CD62L+), TEM (CD45RA−CD62L−), and TEMRA (CD45RA+CD62L−). Quadrant frequencies are indicated. To discriminate between TN and TSCM, which are both CD45RA+CD62L+, double-positive cells are gated and CD95 expression is shown in the bottom row plots. TSCM are identified as CD95+, and TN as CD95−. The percentages of TSCM gated on CD45RA+ CD62L+ CD8+ T lymphocytes are shown. (B) Summary of CD8+ T-cell subset distributions, expressed as percentages on total CD8+ T cells, at the indicated points post-HSCT. (C) Comparison of CD8+ T-cell subset frequencies at day 8 post HSCT. Each dot represents a single patient. (D) Comparison of the absolute numbers of circulating CD8+ T cell subsets at day 8 post-HSCT. (E) Comparison of TSCM frequencies among LP and day 8 post-HSCT. Data are shown as mean values ± SEM of the 20 patients included in the study. (F) Linear regression analysis between CD8+ TSCM counts at day 8 post-HSCT and the serum level of IL-7 measured at day 1 post-HSCT (n = 13). Gray line denotes the best-fit line of the linear regression analysis, whereas black dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval. The r2 and P value of the slope are reported in the upper-right part of the panel.

Donor-derived TSCM lymphocytes are selectively enriched early after haploidentical HSCT. (A) Flow cytometric plots of CD8+ T-cell phenotype from a representative patient (UPN#15) within the LP and at different points after HSCT, as labeled. Top row plots depict the expression of CD45RA and CD62L, which allows the identification of TCM (CD45RA−CD62L+), TEM (CD45RA−CD62L−), and TEMRA (CD45RA+CD62L−). Quadrant frequencies are indicated. To discriminate between TN and TSCM, which are both CD45RA+CD62L+, double-positive cells are gated and CD95 expression is shown in the bottom row plots. TSCM are identified as CD95+, and TN as CD95−. The percentages of TSCM gated on CD45RA+ CD62L+ CD8+ T lymphocytes are shown. (B) Summary of CD8+ T-cell subset distributions, expressed as percentages on total CD8+ T cells, at the indicated points post-HSCT. (C) Comparison of CD8+ T-cell subset frequencies at day 8 post HSCT. Each dot represents a single patient. (D) Comparison of the absolute numbers of circulating CD8+ T cell subsets at day 8 post-HSCT. (E) Comparison of TSCM frequencies among LP and day 8 post-HSCT. Data are shown as mean values ± SEM of the 20 patients included in the study. (F) Linear regression analysis between CD8+ TSCM counts at day 8 post-HSCT and the serum level of IL-7 measured at day 1 post-HSCT (n = 13). Gray line denotes the best-fit line of the linear regression analysis, whereas black dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval. The r2 and P value of the slope are reported in the upper-right part of the panel.

pt-Cy administration eliminates proliferating T cells but does not prevent TSCM accumulation

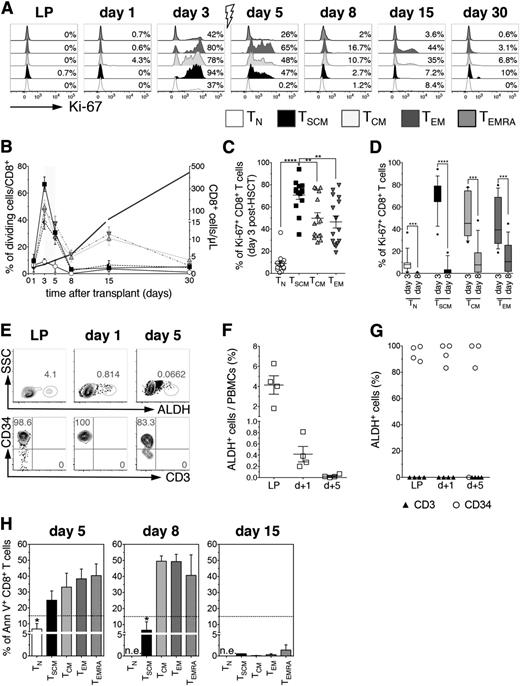

To discern whether the high frequency of TSCM observed at day 8 was a result of expansion of TSCM infused within the graft or their direct in vivo generation, we analyzed T-cell subset proliferation, assessed by Ki-67 staining.17 We hypothesized that TSCM expansion should have been preceded by proliferation of either TSCM or TN lymphocytes, assuming dedifferentiation of TCM or TEM to be unlikely.4 The accumulation of TSCM in this clinical context should also require such proliferating TSCM or TN lymphocytes to survive Cy, either for intrinsic resistance or as a result of temporal uncoupling of proliferation and Cy administration.

At day 3 on in vivo infusion, in the absence of immunosuppressive drugs, all memory CD8+ T-cell subsets robustly proliferated, with TSCM displaying significantly higher frequencies of Ki-67+ cells compared with all other subsets (Figure 2A-C). In contrast, only a minority of TN was Ki-67+, in line with the longer timeframe required for priming (Figure 2A-C). CD4+ T-cell subsets displayed superimposable proliferation kinetics, albeit globally to a lower extent than CD8+ (supplemental Figure 6). Cyclophosphamide is a cytotoxic compound active on proliferating cells, used to purge alloreactive T cells in vivo and prevent GVHD. T-cell proliferation was abrogated after pt-Cy in all subsets (Figure 2D), suggesting effective killing of cycling lymphocytes. However, T-cell counts did not drop between day 5 and day 8 post-HSCT (Figure 2B, gray line, right y axis), and TSCM increased in percentages and counts (Figure 1). These results could be explained either by a selective resistance of cycling TSCM to Cy or by de novo generation of TSCM. We thus explored whether TSCM were resistant to pt-Cy. We failed to record ALDH activity in 3 patients selected according to sample availability, the major mechanism of Cy inactivation,18,19 in total CD3+ T cells neither within the graft nor after in vivo infusion, in contrast with what observed for coexisting CD34+ HSCs, analyzed as internal controls (Figure 2E-F). Accordingly, we detected high percentages of apoptotic cells within all memory subsets at day 5 post-HSCT (1 day after pt-Cy). Noticeably, at day 8, significantly lower percentages of CD8+ TSCM were Annexin V+ compared with TCM, TEM, and TEMRA, whereas by day 15, post-HSCT, all memory subsets displayed very low levels of apoptosis (Figure 2H). Altogether, these results suggest that nonapoptotic day 8 TSCM might stem from de novo differentiation from TN lymphocytes.

pt-Cy administration abrogates T-cell proliferation but does not prevent accumulation of TSCM. (A) Flow cytometry plots depict Ki-67 expression on CD8+ T cell subsets from a representative patient (UPN#20) at different points after HSCT, as labeled. Gray arrow denotes pt-Cy administration. (B) Summary of the percentages of proliferating CD8+ T cell subsets at the indicated points post-HSCT. Gray line designates absolute CD8+ T cell counts. Gray shade indicates pt-Cy administration. (C) Comparison of the percentage of Ki-67+ cells among the different CD8+ T-cell subsets at day 3 post-HSCT (before pt-Cy administration and in the absence of any immunosuppressive agent). (D) Comparison of the percentages of proliferating cells before pt-Cy administration (day 3) and at the point when highest TSCM frequencies were detected (day 8). (E) Flow cytometric plots of ALDH enzymatic activity from a representative patient (UPN#17) of the 4 patients tested for ALDH activity. Top row plots show ALDH+ cells at the labeled points, whereas bottom row plots show CD34 and CD3 expression on ALDH+ gated cells. (F) Scatter plot depicts the mean percentage of circulating ALDH+ cells at the indicated points. (G) Scatter plot shows the belonging lineage of ALDH+ cells at the labeled points: CD34+ cells are indicated with open circles, CD3+ cells with black triangles (n = 4). (H) Percentages of Annexin V+ early apoptotic cells within CD8+ T cell subsets at days 5, 8, and 15 post-HSCT. Dashed black line indicates mean percentage of Annexin V+ cells measured in leukapheresis (n = 3). n.e., not evaluable.

pt-Cy administration abrogates T-cell proliferation but does not prevent accumulation of TSCM. (A) Flow cytometry plots depict Ki-67 expression on CD8+ T cell subsets from a representative patient (UPN#20) at different points after HSCT, as labeled. Gray arrow denotes pt-Cy administration. (B) Summary of the percentages of proliferating CD8+ T cell subsets at the indicated points post-HSCT. Gray line designates absolute CD8+ T cell counts. Gray shade indicates pt-Cy administration. (C) Comparison of the percentage of Ki-67+ cells among the different CD8+ T-cell subsets at day 3 post-HSCT (before pt-Cy administration and in the absence of any immunosuppressive agent). (D) Comparison of the percentages of proliferating cells before pt-Cy administration (day 3) and at the point when highest TSCM frequencies were detected (day 8). (E) Flow cytometric plots of ALDH enzymatic activity from a representative patient (UPN#17) of the 4 patients tested for ALDH activity. Top row plots show ALDH+ cells at the labeled points, whereas bottom row plots show CD34 and CD3 expression on ALDH+ gated cells. (F) Scatter plot depicts the mean percentage of circulating ALDH+ cells at the indicated points. (G) Scatter plot shows the belonging lineage of ALDH+ cells at the labeled points: CD34+ cells are indicated with open circles, CD3+ cells with black triangles (n = 4). (H) Percentages of Annexin V+ early apoptotic cells within CD8+ T cell subsets at days 5, 8, and 15 post-HSCT. Dashed black line indicates mean percentage of Annexin V+ cells measured in leukapheresis (n = 3). n.e., not evaluable.

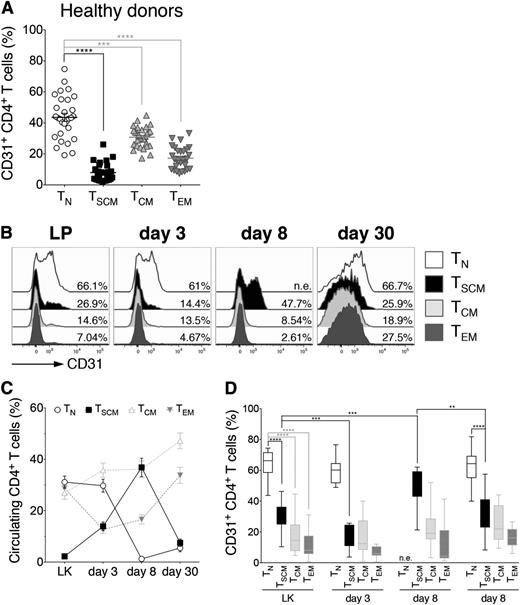

CD4+ TSCM preferentially retain CD31 expression by day 8 post-HSCT

To gain further insight on the possible in vivo differentiation of infused TN lymphocytes into TSCM, we first exploited the peculiar kinetics of CD31 expression. CD4+ TN recently exited from thymus can be identified according to the expression of CD31, which is gradually lost on proliferation.20 Importantly, in healthy adults, only a minority of circulating CD4+ TSCM, TCM, and TEM lymphocytes express CD31 (Figure 3A). We reasoned that upon or after in vivo priming of donor-derived CD4+ TN, CD31 expression could be detected in their progeny if the analyzed point (day 8 post-HSCT) was sufficiently close to the priming to avoid excessive dilution, thereby representing a tool to track TN differentiation by flow cytometry. To verify this hypothesis, purified CD31+ CD4+ TN from 3 healthy subjects were CFSE-labeled and polyclonally stimulated in the presence of IL-7 and IL-15. Eight days after stimulation, CD31 expression was retrieved on the postmitotic progeny of stimulated TN, which had acquired memory features (supplemental Figure 7), indicating that CD31 downregulation kinetics on RTEs can be exploited to track their fate in vivo. Therefore, we analyzed the kinetics of CD31 expression on CD4+ T-cell subsets in our cohort of patients (Figure 3C-E). Similar to healthy controls, within the infused graft, a significantly higher fraction of CD4+ TN expressed CD31 compared with all memory subsets, including TSCM, and the percentages (and expression levels) of CD31+ TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM did not vary until day 3 post-HSCT (Figure 3C-E). Notably, at day 8, when TN disappeared from circulation (Figure 3D), CD31+ clustered predominantly within the TSCM compartment, suggesting recent differentiation from TN precursors. By day 30 post-HSCT, expression of CD31 on CD4+ TSCM was significantly reduced compared with day 8, whereas CD31+ TN were again detectable, in line with de novo generation, confirmed by sjTREC analysis performed on day 30 cells (supplemental Figure 8). Overall, these data suggest that CD31+CD4+ TSCM observed at day 8 post-HSCT preferentially derive from CD31+CD4+ TN infused within the graft.

CD4+ TSCM preferentially retain CD31 expression by day 8 post-HSCT. (A) Box plots depict the differential expression of CD31 on CD4+ T-cell subsets (TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM) from healthy subjects (n = 25). (B) Flow cytometry plots of CD31 expression on CD4+ TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM from a representative patient (UPN#4) at different points after HSCT, as labeled. (C) Kinetics of representation of TN and TSCM, expressed as percentage on the total circulating CD4+ cells at the indicated points post-HSCT. TCM and TEM kinetics are also depicted (gray dashed lines). (D) Box plots show CD31 expression on CD4+ TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM at the labeled points. Data are shown as average values from the 20 patients included in the study. n.e.: not evaluable.

CD4+ TSCM preferentially retain CD31 expression by day 8 post-HSCT. (A) Box plots depict the differential expression of CD31 on CD4+ T-cell subsets (TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM) from healthy subjects (n = 25). (B) Flow cytometry plots of CD31 expression on CD4+ TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM from a representative patient (UPN#4) at different points after HSCT, as labeled. (C) Kinetics of representation of TN and TSCM, expressed as percentage on the total circulating CD4+ cells at the indicated points post-HSCT. TCM and TEM kinetics are also depicted (gray dashed lines). (D) Box plots show CD31 expression on CD4+ TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM at the labeled points. Data are shown as average values from the 20 patients included in the study. n.e.: not evaluable.

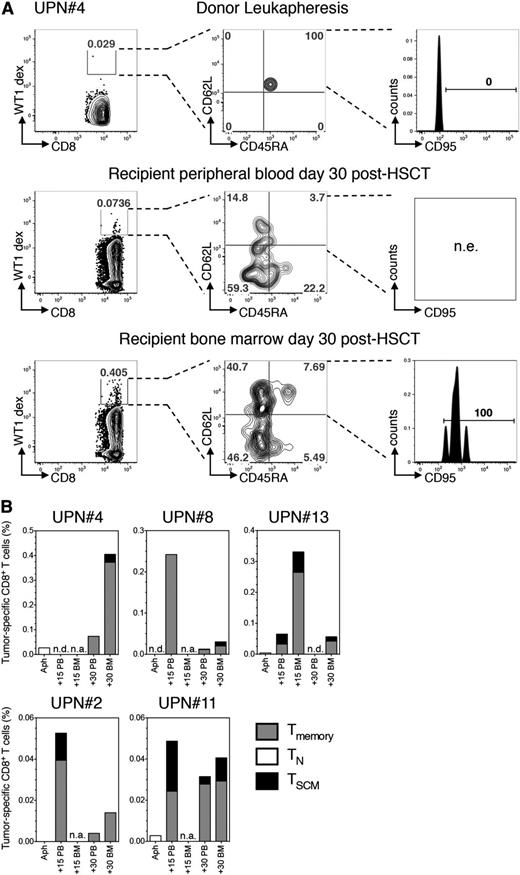

Conversion of CD8+ TN into TSCM can be traced at the antigen-specific level

To trace the differentiation of antigen-specific21 CD8+ TN into TSCM, we exploited HLA-A*0201 and HLA-A*0101 dextramer complexes loaded with known immunogenic peptides from WT122 or PRAME23 in PB or BM of leukemic patients. Tumor-specific T cells are usually rare in healthy subjects and, when detectable, invariantly display a naive phenotype (4). Indeed, in UPN#4, rare HLA-A*0101 restricted WT1-specific T cells retrieved in the donor LP displayed a TN phenotype. By day 30 after HSCT, WT1-specific T cells displayed memory features and were traceable both in PB and at disease site (BM), with TSCM being detectable in the latter (Figure 4A). The same result was obtained in UPN#13, mismatched with the donor for HLA-A*0201. We traced tumor-specific T cells in 3 additional patients receiving a transplant matched for the restriction element analyzed. Of notice, tumor-specific T cells detected in LP displayed a TN phenotype, whereas after infusion, antitumor T cells acquired a memory phenotype in all patients and comprised TSCM lymphocytes, although their relative contribution varied across different anatomical sites and different patients (Figure 4B). In our series, only 1 cytomegalovirus-seropositive HLA-B*0702+ patient was transplanted from a cytomegalovirus-seronegative donor, allowing us to potentially trace a viral-specific primary immune response. Accordingly, pp65-specific T cells in LP displayed a naive phenotype. We observed the appearance of pp65-specific CD8+ TSCM, in concomitance with viral reactivation (supplemental Figure 9). Overall, these observations support direct conversion of human CD8+ TN into TSCM in vivo.

Conversion of CD8+ TN into TSCM can be demonstrated at the antigen-specific level. (A) Identification of WT1-specific CD8+ T cells restricted to the host nonshared HLA-A*0101 by dextramer staining of, from top to bottom, donor LP, day 30 peripheral blood, and day 30 BM harvested from UPN#4. For each point analyzed, left plot depicts the percentage of dextramer-positive CD8+ T cells (WT1-dex). Dextramers carrying the same restriction element but loaded with an irrelevant peptide were used to set the gate and distinguish rare antigen-specific cells from background. Central plot shows CD45RA and CD62L expression on dextramer-positive cells (quadrants are set on the polyclonal CD8+ population). Right plot depicts CD95 expression on CD45RA+CD62L+ cells when detected (CD95 gate is set on the polyclonal CD8+ population). (B) Histograms summarizing the quantification and phenotypic characterization of CD8+ T cells specific for either WT1 (UPN#4, UPN#8, UPN#11, and UPN#13) or PRAME (UPN#2) in 5 patients affected by acute leukemia and with HLA typing suitable for dextramer analysis. For all cytometric dextramer acquisitions, no fewer than 1 × 106 cells were stained and no fewer than 105 events on the CD3+ gate were recorded. n.a., sample not available; n.e., population not evaluable.

Conversion of CD8+ TN into TSCM can be demonstrated at the antigen-specific level. (A) Identification of WT1-specific CD8+ T cells restricted to the host nonshared HLA-A*0101 by dextramer staining of, from top to bottom, donor LP, day 30 peripheral blood, and day 30 BM harvested from UPN#4. For each point analyzed, left plot depicts the percentage of dextramer-positive CD8+ T cells (WT1-dex). Dextramers carrying the same restriction element but loaded with an irrelevant peptide were used to set the gate and distinguish rare antigen-specific cells from background. Central plot shows CD45RA and CD62L expression on dextramer-positive cells (quadrants are set on the polyclonal CD8+ population). Right plot depicts CD95 expression on CD45RA+CD62L+ cells when detected (CD95 gate is set on the polyclonal CD8+ population). (B) Histograms summarizing the quantification and phenotypic characterization of CD8+ T cells specific for either WT1 (UPN#4, UPN#8, UPN#11, and UPN#13) or PRAME (UPN#2) in 5 patients affected by acute leukemia and with HLA typing suitable for dextramer analysis. For all cytometric dextramer acquisitions, no fewer than 1 × 106 cells were stained and no fewer than 105 events on the CD3+ gate were recorded. n.a., sample not available; n.e., population not evaluable.

In vivo fate mapping by TCR clonotyping uncovers the differentiation landscapes of TN after transplant

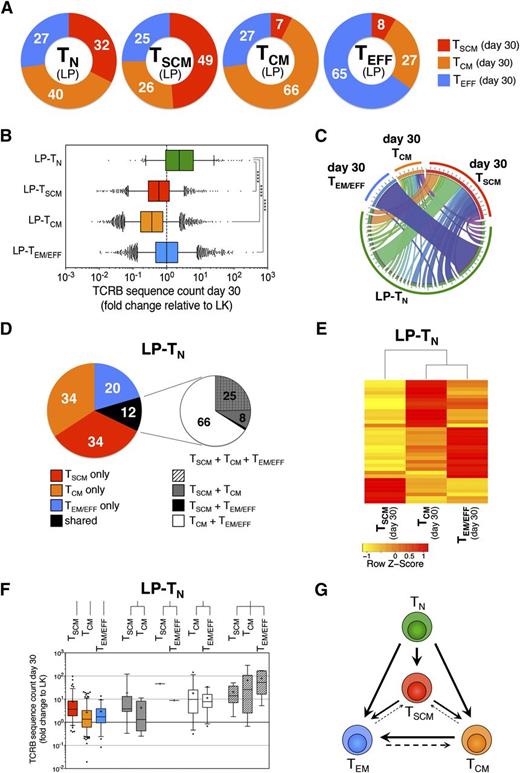

To assess the relevance of in vivo differentiation of TSCM from TN after transplant, we exploited the TCR sequences harbored by individual T lymphocytes as surrogate clonal markers to track T-cell fate on infusion. CD3+ TN, TSCM, TCM, and TEM/EFF were FACS-purified from LP and PBMCs harvested 30 days after HSCT in 3 consecutive patients and were subjected to TCRB CDR3 deep sequencing. First, we observed that the TCRB repertoire detected at day 30 in TN did not overlap with that of the other T-cell subsets retrieved at day 30 (supplemental Figure 10), suggesting the majority of day 30 TN arise from de novo generation. For longitudinal evaluation, CDR3 TCRB in-frame nucleotide sequences unique to each T-cell subset within LP samples were identified. These specific rearrangements were used to estimate qualitatively and quantitatively the fate after infusion of T cells bearing a specific differentiation phenotype within LP. As expected, sequences harbored by TN lymphocytes within LP were retrieved in all memory subsets at day 30, showing that after HSCT, TN are able to generate the complete spectrum of immunological memory, including TSCM, that represented, on average, 32% of memory T cells (Figure 5A), implying that during TN differentiation after transplant, a high number of TSCM is generated. Similarly, TCRB sequences originally harbored by LP-TSCM were found in all memory subsets at day 30 post-HSCT. Conversely, sequences present in LP-TCM were retrieved preferentially in TCM and TEM/EFF repertoires at day 30 post-HSCT, whereas fewer than 10% were found in the TSCM repertoire. Sequences harbored by LP-TEM/EFF were found mainly within day 30 TEM/EFF, although conversion into TCM was also observed (27%). Again, less than 10% of TCRB sequences identified in LP-TEM/EFF were retrieved in the TSCM compartment at day 30 (Figure 5A). These data are consistent with a preferential progressive framework of differentiation, following the pathway TN→TSCM→TCM→TEM/EFF, but still allowing for a certain degree of plasticity within each memory subset. Quantitative analysis revealed that only clonotypes originally harbored by LP-TN were significantly increased in counts at day 30 post-HSCT, regardless of the subsets in which they were identified after transplant (Figure 5B depicting 1 representative patient; supplemental Figures 11 and 12 for the remaining 2 patients analyzed). In accordance with flow-cytometric data (Figure 2), sequences unique to LP-TSCM, LP-TCM, or LP-TEM/EFF were similar or reduced in counts at day 30 post-HSCT compared with LP, indicating that pt-Cy efficiently dampened their expansion and that possibly only memory lymphocytes that remained unchallenged on in vivo infusion could survive pt-Cy (Figure 5B; supplemental Figures 11 and 12). T-cell responses are characterized by the clonal burst of the ancestor lymphocyte recognizing its antigen. Given the absence of expansion on infusion, LP-TSCM, LP-TCM, and LP-TEM/EFF clonotypes were not considered informative enough to study memory T-cell dynamics in this transplant setting, and we focused on LP-TN. To gain insight into the differentiation routes adopted by TN on priming, we evaluated the overlap of the TCRB repertoire from LP-TN with that of memory subsets retrieved at day 30 post-HSCT. The majority (on average, 80%) of clonotypes of LP-TN lymphocytes retrieved 30 days after transplant displayed a unique differentiation phenotype, with TSCM and TCM being more represented than TEM/EFF. Only 12% of LP-TN TCRB sequences were found in multiple memory subsets (Figure 5C-D; supplemental Figure 13). By focusing on those LP-TN-derived sequences that were shared among 2 or more memory subsets at day 30 post-HSCT, we found that approximately 25% of TCRB sequences were shared among day 30 TSCM, TCM, and TEM/EFF, although all other possible combinations could be retrieved (Figure 5D-E). The frequency of memory T-cell clones originating from individual LP-TN was highly variable and was proportional to the level of memory subset diversification retrieved at day 30 post-HSCT (Figure 5F), suggesting that the single-cell progenies differentiating into multiple subsets were those characterized by the highest clonal burst. Although the relative contribution of single vs multiple fates of TN could not be determined, our in vivo fate mapping suggests that in the HSCT context, progenies of single TN might embrace disparate fates, with phenotypic and functional heterogeneity achieved at population level. Thus, we propose a revision of the linear differentiation model to take into account the discordance in fate of individual TN and the intrinsic plasticity of the memory compartment, leading to a branched differentiation model (Figure 5G).

In vivo fate mapping by TCR clonotyping uncovers the differentiation landscapes of TN after transplant. (A) Graphic representation of the distribution within day 30 memory T-cell subsets of the TCRB sequences harbored by a given T-cell subset from LP. Numbers in donut graphs indicate the average percentages, from the 3 patients analyzed, of TCRB sequences retrieved in the indicated memory subsets 30 days after HSCT. (B) Quantification of the expansion ability of single-cell progenies of T lymphocytes with a given phenotype within LP, independent of the memory T-cell subset in which they were retrieved at day 30 post-HSCT. Expansion is measured as fold change of TCRB sequence count at day 30 relative to LP from a representative patient (UPN#12). (C) Circos plot16 graphically summarizes the distribution of TCRB sequences originally harbored by LP-TN in a representative patient (UPN#12) of the 3 analyzed. LP-TN sequences are depicted in the bottom part of the circle, identified by the green band. From each LP-TN-derived TCRB sequence departs a ribbon connecting it to 1 or more memory subsets at day 30 post-HSCT. Each day 30 memory subset is denoted by a colored band (red for TSCM, orange for TCM, and blue for TEM/EFF). Ribbon thickness is proportional to the TCRB sequence count of the given clonotype at day 30 post-HSCT. (D) Left pie chart shows the distribution at day 30 after transplant of the TCRB sequences originally harbored by LP-TN. Numbers in the pie indicate the average percentages from the 3 patients analyzed; right chart zooms on the fraction of clonotypes that were found shared among 2 or more subsets at day 30 post-HSCT and depicts the mean distribution of all combinations retrieved. (E) Spearman correlation heat map representing the contribution of individual LP-TN-derived clonotypes (row) to the repertoire of TSCM, TCM, and TEM/EFF subsets at day 30 post-HSCT (columns). The analysis is performed to LP-TN TCRB sequences that are shared by at least 2 memory T-cell subsets at day 30 post-HSCT. (F) Box plots quantify the expansion, measured as count fold change relative to LP, of LP-TN TCRB sequences that were retrieved in memory T-cell subsets at day 30 post-HSCT. (G) Model scheme of a proposed branched diversification pathway from TN to TSCM, TCM, and TEM/EFF subsets on in vivo transfer after HSCT.

In vivo fate mapping by TCR clonotyping uncovers the differentiation landscapes of TN after transplant. (A) Graphic representation of the distribution within day 30 memory T-cell subsets of the TCRB sequences harbored by a given T-cell subset from LP. Numbers in donut graphs indicate the average percentages, from the 3 patients analyzed, of TCRB sequences retrieved in the indicated memory subsets 30 days after HSCT. (B) Quantification of the expansion ability of single-cell progenies of T lymphocytes with a given phenotype within LP, independent of the memory T-cell subset in which they were retrieved at day 30 post-HSCT. Expansion is measured as fold change of TCRB sequence count at day 30 relative to LP from a representative patient (UPN#12). (C) Circos plot16 graphically summarizes the distribution of TCRB sequences originally harbored by LP-TN in a representative patient (UPN#12) of the 3 analyzed. LP-TN sequences are depicted in the bottom part of the circle, identified by the green band. From each LP-TN-derived TCRB sequence departs a ribbon connecting it to 1 or more memory subsets at day 30 post-HSCT. Each day 30 memory subset is denoted by a colored band (red for TSCM, orange for TCM, and blue for TEM/EFF). Ribbon thickness is proportional to the TCRB sequence count of the given clonotype at day 30 post-HSCT. (D) Left pie chart shows the distribution at day 30 after transplant of the TCRB sequences originally harbored by LP-TN. Numbers in the pie indicate the average percentages from the 3 patients analyzed; right chart zooms on the fraction of clonotypes that were found shared among 2 or more subsets at day 30 post-HSCT and depicts the mean distribution of all combinations retrieved. (E) Spearman correlation heat map representing the contribution of individual LP-TN-derived clonotypes (row) to the repertoire of TSCM, TCM, and TEM/EFF subsets at day 30 post-HSCT (columns). The analysis is performed to LP-TN TCRB sequences that are shared by at least 2 memory T-cell subsets at day 30 post-HSCT. (F) Box plots quantify the expansion, measured as count fold change relative to LP, of LP-TN TCRB sequences that were retrieved in memory T-cell subsets at day 30 post-HSCT. (G) Model scheme of a proposed branched diversification pathway from TN to TSCM, TCM, and TEM/EFF subsets on in vivo transfer after HSCT.

Discussion

Although stem cell engraftment and hematological reconstitution are carefully monitored during the first month after HSCT, the shape of T-cell dynamics within this timeframe has remained largely unknown so far. Here, we exploited the pt-Cy platform that, in contrast to other HSCT protocols that mainly rely on the infusion of antithymocyte globulins, permits a thorough analysis of circulating cells in this delicate early posttransplant phase, which allows us to explore the contribution of TSCM to posttransplant IR. Indeed, we observed that donor-derived TSCM lymphocytes are highly enriched early after HSCT, and we showed, at the polyclonal, antigen-specific, and clonal level, that TSCM lymphocytes arising soon after HSCT preferentially derive from differentiation of TN infused within the graft, whereas most memory lymphocytes are purged by pt-Cy. The observation that Cy differentially affects naive and memory T cells in vivo, because of their different activation kinetics, might provide novel hints on the cellular determinants of alloreactivity after transplant, which is a matter of intense debate in the field.24,25 Indeed, our results, crossed with the high clinical efficacy of pt-Cy in preventing GVHD after HLA-matched26 and haploidentical HSCT,27-29 suggest that alloreactivity in humans largely segregates with infused memory lymphocytes and is thereby likely fueled by cross reactivity.30 In contrast, our results imply that the surviving progenies of TN in this specific HSCT setting acquire a leading role in guiding IR. Given the observed high fraction of TN that differentiates into TSCM after transplant, it will be important to include CD95 in future studies aiming at deciphering IR kinetics after allogeneic HSCT, to avoid TN overestimation, and to quantify the contribution of TSCM.

Notably, we showed that IL-7 serum levels measured 1 day after graft infusion seem to correlate with circulating TSCM counts at day 8, thereby suggesting that IL-7 might be important for TSCM generation not only in vitro5 but also in vivo. The cytokine milieu in which T cells are activated may differently promote effector vs memory differentiation.31,32 We could speculate that the increase in circulating IL-7 levels characteristic of the early phase post-HSCT, and associated with the lymphopenic environment, may have favored TSCM generation in this specific context, as also suggested by murine studies.33 Thus, it remains to be evaluated whether these results could be confirmed in other relevant human settings, such as longitudinal studies on vaccinations or chronic infections, where IL-7 is not elevated and other possibly confounding variables, such as postgrafting pharmacological immune suppression with mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus that could influence T-cell metabolism and differentiation, are not present. Of notice, Roberto et al34 report in this issue of Blood that in a similar transplant setting, transferred naive T cells rapidly differentiate into TSCM, which subsequently reconstitute the posttransplant T-cell compartment. Importantly, our work and the work by Roberto et al rely on 2 separate models of haploidentical HSCT with major differences in the conditioning regimen used (myeloablative vs nonmyeloablative), stem cell source (peripheral blood vs bone marrow), postgrafting GVHD prophylaxis (mTOR inhibitors vs calcineurin inhibitors), and disease background (acute leukemia vs lymphoma). Regardless of these important differences, both studies ultimately reach a similar model of human T-cell differentiation, with a predominant role played by TSCM lymphocytes, thus suggesting that generation of TSCM after transplant is not deeply influenced by any of these variables. It remains to be elucidated whether such an IR profile could also be observed in pediatric patients undergoing haploidentical HSCT with pt-Cy.

Several lines of evidence support the relevance of our findings in other clinical contexts. Approximately 30% of virus-specific memory cells in yellow fever-vaccinated subjects have been reported to express CD45RA and CCR7 and to persist for years.35,36 Similarly, another study identified CD45RA+CCR7+ HIV-specific CD8+ memory T cells functioning as precursors for the other subsets of memory lymphocytes.37 Notably, in EBV carriers, 10% of EBV-specific memory CD4+ T cells coexpress CD45RA and CCR7.38 Although formal proof that such cells represented TSCM lymphocytes was missing in these reports, these findings strongly support the hypothesis that TSCM lymphocytes are reproducibly generated after immunization in humans. Differences in the insulting pathogens and tissue environments might impinge on the relative abundance of TSCM generated. Here, we show that TSCM have the potential to emerge early after TN priming, without necessarily passing through an effector stage.

The mechanisms of T-cell memory formation have been actively debated and several models proposed to explain the divergent developmental fates of T-cell progenies. By exploiting the TCR harbored by single T cells infused within the leukapheresis product as surrogate clonal markers, we attempted to evaluate the in vivo differentiation landscapes of single T-cell progenies after transplant in 3 consecutive patients. Obviously, in the absence of access to secondary lymphoid organs, peripheral or mucosal tissues, which are constraints typical of studies involving human subjects, we relied on PB as barometer of the entire organism, and tissue-resident progenies of infused lymphocytes could not be included in the present model. With this caveat in mind, we found that after transfer, discrete T-cell subsets behaved preferentially within a progressive framework of differentiation: infused TN and TSCM were able to reconstitute the entire spectrum of T-cell memory. Interestingly, up to 30% of cells originally TEM could revert to a TCM phenotype, as reported in nonhuman primates.39 A limited fraction of TCM and TEM reconverted to TSCM, indicating that the T-cell memory compartment is endowed with a certain degree of plasticity in vivo. Our experimental system was characterized by the use of pt-Cy, which we showed to selectively kill the majority of memory T cells proliferating early after transplant. As a result, TCRB sequences originally harbored by LP-TSCM, LP-TCM, and LP-TEM were found decreased in counts 30 days after transplant. Differently, TN were capable of robustly proliferating and differentiating into memory cells. Progenies of individual TN were plastic and had the ability to generate heterogeneous effector and memory populations comprising TSCM. Notably, the experimental evidence that a third of LP-TN clonotypes traced 30 days after HSCT were found within the TSCM compartment argues against the hypothesis that TSCM may represent a metastable state within a continuum of phenotypes but, rather, reinforces the notion that they represent a stable and relevant memory subset. In our study, only a small proportion of TN-progenies were traceable in multiple subsets at day 30, whereas the majority of TN clones identified in LP were retrieved in a single memory subclass in vivo. Although the relative contribution of single vs multiple cell fates could not be precisely estimated, our data suggest that the rules of memory T-cell differentiation in humans are at least in part based on population averaging of disparate single-cell behaviors and are reminiscent of the T-cell dynamics recently described in murine models.6,7,10

Altogether, these results highlight TSCM lineage as a previously unappreciated important player in the diversification of TN and will likely inform strategies aimed at preventing and treating infections,40 autoimmune diseases,41 and cancer.42

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. R. Riddell (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle) for inspiring discussion and continuous advice as second supervisor of N.C., and A. Ambrosi (San Raffaele University) for statistical support.

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (GR07-5 BO, RO10/07-B-1, RF-09-149), Italian Ministry of Research and University (FIRB-IDEAS), Fondazione Cariplo, Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC Investigator Grant and AIRC 5x1000), European Commission of the Seventh Framework Program for Research and Technical Development (SUPERSIST, ATTACK2), Regione Piemonte (Direzione Sanità Settore Promozione della Salute e Interventi di Prevenzione Individuale e Collettiva), FIRB Accordi di Programma 2011 (RBAP11T3WB-RNA e nanotecnologie nel controllo dell’immunosoppressione neoplastica sostenuta dal catabolismo degli aminoacidi), and Eranet Transcan Haplo_immune.

Authorship

Contribution: N.C. designed the study, conducted laboratory experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; G.O. performed and analyzed experiments; B.C., V.V., and M.N. assisted in sample processing; M.F., C.T., and S.B. performed bioinformatics analyses; J.P. and R.G. helped in designing the study, provided clinical data and samples, and participated in data analyses and interpretation of results; L.V., A.B., and C. Bordignon participated in data discussion; S.M. and F.L. provided clinical samples; L.B. provided leukapheresis samples; and F.C. and C. Bonini supervised the study and wrote the paper. N.C. conducted this study as partial fulfillment of her PhD in cellular and molecular biology, and G.O. as partial fulfillment of his PhD in molecular medicine, San Raffaele University.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C. Bordignon is an employee of and C. Bonini has a research contract with MolMed S.p.A. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Chiara Bonini, Experimental Hematology Unit, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, via Olgettina 60, Milano, Italy; e-mail: bonini.chiara@hsr.it.

References

Author notes

F.C. and C.B. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal