Key Points

TSCM are abundant early after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and derive from naive T cells that survived pt-Cy.

Pt-Cy allows the generation of donor primary and recall responses in transplanted patients, even in the presence of persistent antigen.

Abstract

Early T-cell reconstitution following allogeneic transplantation depends on the persistence and function of T cells that are adoptively transferred with the graft. Posttransplant cyclophosphamide (pt-Cy) effectively prevents alloreactive responses from unmanipulated grafts, but its effect on subsequent immune reconstitution remains undetermined. Here, we show that T memory stem cells (TSCM), which demonstrated superior reconstitution capacity in preclinical models, are the most abundant circulating T-cell population in the early days following haploidentical transplantation combined with pt-Cy and precede the expansion of effector cells. Transferred naive, but not TSCM or conventional memory cells preferentially survive cyclophosphamide, thus suggesting that posttransplant TSCM originate from naive precursors. Moreover, donor naive T cells specific for exogenous and self/tumor antigens persist in the host and contribute to peripheral reconstitution by differentiating into effectors. Similarly, pathogen-specific memory T cells generate detectable recall responses, but only in the presence of the cognate antigen. We thus define the cellular basis of T-cell reconstitution following pt-Cy at the antigen-specific level and propose to explore naive-derived TSCM in the clinical setting to overcome immunodeficiency. These trials were registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02049424 and #NCT02049580.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is a potentially curative approach for blood cancers. Patients benefit from the graft-versus-tumor effect exerted by alloreactive T cells, although, at the same time, they may suffer from graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), especially in the context of T-replete transplantations. Immunosuppressants are, unfortunately, not selective for alloreactive T cells and may thus limit adaptive immune responses to opportunistic infections and cancer.1 Depletion of T cells from the allograft prevents GVHD but results in delayed reconstitution and increased morbidity and mortality due to opportunistic infections and tumor relapse.2 High-dose cyclophosphamide given early posttransplant (pt-Cy) has been proposed to selectively spare bystander naive and memory T cells while depleting alloreactive T cells in vivo after infusion of unmanipulated grafts.3-8 Indeed, the latter are thought to proliferate quickly in the alloantigen-replenished environment, thus becoming susceptible to pt-Cy, while the former survive and promote reconstitution.9

In the first months, immune competence is in part restored in a thymus-independent fashion by proliferation of the T cells in response to increased levels of homeostatic cytokines or exogenous antigens.1,10 Production of new T cells occurs only later by resumed thymic output.10 The unmanipulated graft contains subsets of naive and memory T cells with defined specificities that display distinct proliferative and persistence capacities in response to lymphopenia.11,12 In particular, a population of early-differentiated human memory T cells with stem cell–like properties (the T memory stem cells [TSCM]) has been reported to preferentially reconstitute immunodeficient mice compared with more differentiated central memory (TCM) and effector memory (TEM) T cells.13 A recent study suggested that the posttransplant lymphopenic environment may favor the generation of TSCM from naive precursors.14 Nevertheless, naive or TSCM cells are relatively absent early after transplantation,3,15-17 thus rendering unclear to what extent these T-cell subsets contribute to reconstitution. The persistence and expansion of the transferred T cells would confer protection toward opportunistic infections and cancer. In this regard, whether pt-Cy differentially affects donor T-cell subsets at the polyclonal and antigen-specific levels remains undetermined.

Materials and methods

Patients and transplantation procedures

Thirty-nine consecutive patients were treated according to the haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (haplo-HSCT) protocol established by Luznik et al.4 All experiments display biological replicates from different patients or healthy donors who were randomly selected, unless specified (such as for the study of antigen-specific responses). Details about the transplantation procedure are available in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site). Patient characteristics are listed in supplemental Table 1. Patients and donors signed consent forms in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Clinical and experimental protocols were approved by the institutional review board of Humanitas Research Hospital and Istituto Nazionale Tumori.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Monoclonal antibodies (described in supplemental Methods) were purchased from BD Biosciences and BioLegend, unless specified otherwise, or conjugated in-house (http://www.drmr.com/abcon). Frozen cells were thawed and prepared for flow cytometry as described previously.18 Chemokine receptor expression was revealed by incubating cells at 37°C for 20 minutes. The Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) was used to detect intracellular Ki-67.19 T-cell subsets were defined as depicted in supplemental Figure 1B and as described in supplemental Methods. Cells were stained for 15 minutes at room temperature with Aqua viability dye (Life Technologies). Samples were acquired on a Fortessa flow cytometer or separated via a FACS Aria (all from BD Biosciences). Absolute lymphocyte numbers were obtained from the Humanitas Cancer Center.

Cell stimulations and treatments

Cells were seeded at 0.25 × 106 cells/mL. Cell proliferation was determined by the analysis of 5-(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; used at 5 μM; Life Technologies) dilution. Cells were stained at 37°C for 7 minutes, washed in complete medium, and stimulated with rhIL-15 (Peprotech) for 8 to 10 days. Patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) at different times post–haplo-HSCT (n = 5; day 41, day 53, day 56, day 57, and day 65) are shown in Figure 2D.

To induce cytokine production, PBMCs (final volume, 200 μL) were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 10 ng/mL) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL) (both from Sigma Aldrich) for 4 hours in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences), as described previously.19 To detect antigen-specific T cells by intracellular cytokine staining, PBMCs were stimulated for 16 hours with a cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp65 peptide pool (15-mer peptides overlapping by 11; JPT Technologies; 1 μg/mL per peptide) or with VAXIGRIP seasonal influenza vaccine (Sanofi; 1:40 vol/vol). Intracellular cytokine production was revealed as described previously.19

In mixed lymphocyte reaction cultures, highly purified naive T cells (TN) and memory T cells were cultured at 1:1 ratio with major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-mismatched antigen-presenting cells (allo-APCs) or autologous APCs (auto-APCs) (both sorted as CD3−CD56− mononuclear cells). To block APC:T-cell interaction, anti-MHC class I and class II antibodies were used (clones G46-2.6 and Tu39, respectively; 10 μg/mL). Nonalloreactive T cells were identified by gating either on CFSEhi cells or on CD25−CD69− cells.

Enumeration of antigen-specific T cells by MHC class I tetramers

The peptide:MHC class I tetramers used in the study are described in supplemental Methods. Staining was conducted at 37°C for 15 minutes. To detect Wilms tumor 1 (WT1)-positive cells, tetramers recognizing 3 different WT1 epitopes were combined. CD8+ T cells were enriched by negative magnetic sorting (STEMCELL Technologies) from 10 to 30 × 106 PBMCs prior to staining. Between 0.3 and 3 × 106 CD8+ T cells were acquired. For MART-1 and WT1, the percent threshold of positivity (0.003926 and 0.003705, respectively) was set as the 75th percentile of distributions resulting from the percentage of tetramer-binding cells in CD4+ T cells. Only 1 representative threshold is depicted in Figure 4D for simplicity.

Clonotypic analysis of antigen-specific T cells

Preliminary peptide mapping experiments were conducted to identify donor and recipient CMV-specific T cells responding to the same pool of 12 peptides, as described previously.20 Aqua−CD14−CD3+CD4/CD8+ T cells producing interferon-γ (IFN-γ) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) were sorted into 1.5-mL tubes (Sarstedt; median of sorted cells, 3901; range, 712-30 030). Clonotypic composition was determined using a DNA-based multiplex polymerase chain reaction for TCRB gene rearrangements.21

Analysis of donor chimerism

Donor chimerism was determined by polymerase chain reaction analysis of short tandem repeats as described previously.22

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using GraphPad PRISM (6.0b) and SPICE 5.22 software.23 The nonparametric paired Wilcoxon rank test and unpaired Mann-Whitney test were used to compare 2 groups. Differences in the pie-chart distributions were calculated with SPICE software using a permutation test. P values are 2 sided and were considered significant when ≤.05.

Results

T-cell dynamics following haplo-HSCT

We first evaluated the reconstitution patterns of major T-cell subsets. The characteristics of the patients included in the study, discussed in a previous publication,5 are shown in supplemental Table 1. Absolute counts at specific time points up to 1 year after haplo-HSCT (supplemental Figure 1A) are reported in supplemental Figure 2A. Counts of total T cells were undetectable in most of the patients up to 6 weeks post–haplo-HSCT. Rapid increases were observed from week 6, when mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and were followed by equally rapid declines at week 9. These declines were possibly caused by the apoptotic loss of highly activated effector cells.24 Subsequently, T cells progressively recovered over time (supplemental Figure 2A). A flow cytometry panel detecting naive and memory subsets (supplemental Figure 1B) revealed that recovering T cells predominantly displayed a transitional memory (TTM), TEM, or terminal effector (TTE) phenotype (supplemental Figures 2B and 3). These dynamics paralleled the proliferation (ie, Ki-67+) of multiple subsets (supplemental Figure 4). Single-cell analysis of the mismatched HLA in circulating CD3+ (supplemental Figure 2C) or chimerism analysis of sorted CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (supplemental Figure 2D) confirmed donor-dependent T-cell reconstitution, as previously reported.5

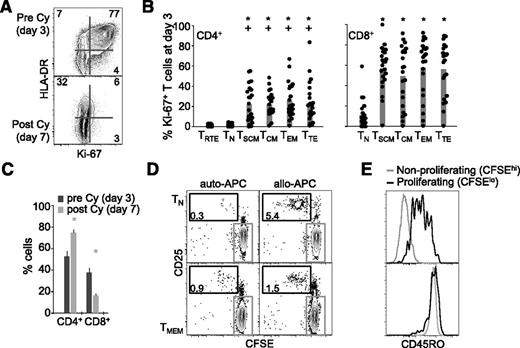

Pt-Cy preferentially depletes proliferating effector/memory T cells

To gain insights into the mechanisms of pt-Cy effect on naive and memory cells, we analyzed the T-cell compartment within a few days following transplantation. Cyclophosphamide (Cy) preferentially depletes proliferating cells. We collected peripheral blood (PB) before (day 3) and after pt-Cy (ie, at day 7). The vast majority of CD3+ T cells at day 3 expressed markers of proliferation (Ki-67) and activation (HLA-DR; Figure 1A). In vivo treatment with Cy depleted proliferating cells (Figure 1A), thereby indicating that Ki-67 is a surrogate marker of Cy susceptibility. In healthy individuals, Ki-67 is preferentially expressed by memory-phenotype T cells.11 Combined analysis of Ki-67 expression and naive and memory markers (supplemental Figure 1B) revealed that Ki-67 expression was confined to memory subsets while both CD4+ and CD8+ TN were almost exclusively Ki-67− (Figure 1B). Similar trends were confirmed by gating on donor-derived T cells, as identified by the mismatched HLA (supplemental Figure 5A). Overall, CD4+ proliferated less compared with CD8+ T cells (Figure 1B), hence resulting in their preferential accumulation following pt-Cy (Figure 1C). Similar to conventional CD4+ T cells, circulating CD4+CD25+CD127− regulatory T (TREG) cells (supplemental Figure 5B) with a naive phenotype (ie, CD45RO−CCR7+CD45RA+; supplemental Figure 5C-D) increased following pt-Cy (supplemental Figure 5C), presumably due to their lower proliferation compared with memory cells at day 3 (supplemental Figure 5E). Overall, TREG tended to express lower Ki-67 levels than conventional CD4+ T cells (supplemental Figure 5E and Figure 1B, respectively), suggesting that they are preferentially spared by pt-Cy in vivo, as recently reported in vitro.25

Pt-Cy preferentially depletes proliferating effector/memory T cells. (A) Representative (out of 10) Ki-67 and HLA-DR expression in PB CD3+ T cells at day 3 and day 7 post–haplo-HSCT. (B) Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) frequency (n = 22; each dot represents a patient) of Ki-67+ T cells with a given differentiation phenotype at day 3 post–haplo-HSCT. +P < .05 vs TRTE; *P < .05 vs TN; Wilcoxon test. (C) Mean ± SEM frequency (n = 23) of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at day 3 and day 7 post–haplo-HSCT. P < .05 vs day 3; Wilcoxon test. (D) CFSE dilution and CD25 expression by TN and TMEM following incubation with auto-APCs or allo-APCs for 3 days. The gate in black identifies CFSElo proliferating (ie, alloreactive) cells, whereas that in gray CFSEhi nonproliferating cells. (E) CD45RO expression by CFSElo and CFSEhi cells, identified as in panel D, originally sorted as TN (top) or TMEM (bottom).

Pt-Cy preferentially depletes proliferating effector/memory T cells. (A) Representative (out of 10) Ki-67 and HLA-DR expression in PB CD3+ T cells at day 3 and day 7 post–haplo-HSCT. (B) Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) frequency (n = 22; each dot represents a patient) of Ki-67+ T cells with a given differentiation phenotype at day 3 post–haplo-HSCT. +P < .05 vs TRTE; *P < .05 vs TN; Wilcoxon test. (C) Mean ± SEM frequency (n = 23) of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at day 3 and day 7 post–haplo-HSCT. P < .05 vs day 3; Wilcoxon test. (D) CFSE dilution and CD25 expression by TN and TMEM following incubation with auto-APCs or allo-APCs for 3 days. The gate in black identifies CFSElo proliferating (ie, alloreactive) cells, whereas that in gray CFSEhi nonproliferating cells. (E) CD45RO expression by CFSElo and CFSEhi cells, identified as in panel D, originally sorted as TN (top) or TMEM (bottom).

It has been shown that alloreactive T cells preferentially derive from CD45RA+ TN.26,27 The preferential expression of Ki-67 by donor memory T cells and their subsequent depletion therefore seems counterintuitive. Moreover, it has been proposed that memory cells are relative resistant to Cy treatment.3,25 To better clarify these aspects, we incubated highly purified naive or memory T cells with allo-APCs or control auto-APCs. T-cell activation induces the rapid loss of CD45RA and the upregulation of CD45RO, thereby suggesting that the Ki-67+ memory fraction at day 3 (Figure 1B) also contains allogeneic cells from the TN pool. Incubation of CD4+ TN or CD45RO+ memory T (TMEM) cells with allo-APCs, but not auto-APCs, for 3 days led to the proliferation (CFSE dilution) and upregulation of CD25 in a fraction of T cells (Figure 1D), indicating that alloreactivity resides in both subsets. CFSElo cells from TN, originally fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) sorted as CD45RO−, uniformly upregulated CD45RO compared with CFSEhi cells (Figure 1E). These results indicate that the Cy-sensitive Ki-67+ fraction at day 3, exclusively identified by memory phenotypes, contains cells originating from both TN and memory T cells.

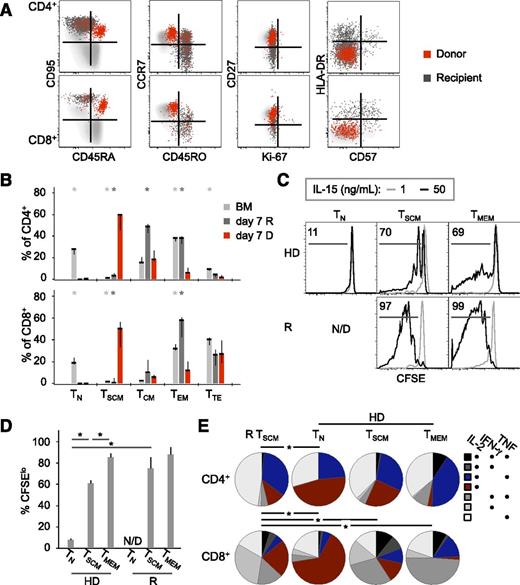

Donor TSCM cells dominate the peripheral T cell compartment following pt-Cy

Next, we investigated the events occurring in the circulation following pt-Cy. Given that only donor T cells are responsible for peripheral reconstitution, we analyzed the composition of the donor and recipient T cells by using HLA-specific antibodies in suitable patients. Although recipient T cells were preferentially memory (with some differences between the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in terms of TCM, TEM, and TTE distribution; Figure 2A-B), including activated (HLA-DR+) and senescent (CD57+) cells11 (Figure 2A), donor cells predominantly expressed markers of naivety as well as CD95, thus resembling TSCM (Figure 2A-B).11,13 Notably, the frequencies of TSCM among the donor populations largely exceeded those observed in the bone marrow (BM; Figure 2B) and in the PB of donors (typically 2% to 3% of total T cells).13 These TSCM were present also in the following weeks post–haplo-HSCT but were gradually replaced by more differentiated TCM and TEM (supplemental Figure 6).

Donor TSCM dominate the peripheral T-cell compartment following pt-Cy. (A) FACS analysis of PB T cells at day 7 post–haplo-HSCT. Donor (D; red) and recipient (R; dark gray) cells are identified by an antibody recognizing the mismatched HLA-A*02. Light-gray cells in the background are T cells from the PB of a healthy donor. (B) Median ± SEM frequency of D and R T cells (identified as in panel A) with a given differentiation phenotype in patients at day 7 post–haplo-HSCT (n = 7, CD4+; n = 6, CD8+). Only donor-recipient pairs whose mismatched HLA could be investigated by flow cytometry are included. *P < .05 vs day 7 D cells; Mann-Whitney test. (C) Percent CFSElo CD8+ T cell subsets from a healthy donor (HD) and a recipient (R) at day 41 post–haplo-HSCT after PBMC culture with 1 (gray, serving as a nonproliferating control) or 50 ng/mL IL-15 (black) for 8 days. N/D, not detected. (D) Mean ± SEM CFSElo CD8+ T-cell subsets (calculated as in panel C) from healthy donors (n = 6) and haplo-HSCT patients (n = 5). TMEM, CD45RO+ memory T cells. *P < .05, Mann-Whitney test. (E) Combinations of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF production in gated TSCM from patients (n = 3) and in T-cell subsets from healthy donors (HD; n = 4). *P < .05, permutation test.

Donor TSCM dominate the peripheral T-cell compartment following pt-Cy. (A) FACS analysis of PB T cells at day 7 post–haplo-HSCT. Donor (D; red) and recipient (R; dark gray) cells are identified by an antibody recognizing the mismatched HLA-A*02. Light-gray cells in the background are T cells from the PB of a healthy donor. (B) Median ± SEM frequency of D and R T cells (identified as in panel A) with a given differentiation phenotype in patients at day 7 post–haplo-HSCT (n = 7, CD4+; n = 6, CD8+). Only donor-recipient pairs whose mismatched HLA could be investigated by flow cytometry are included. *P < .05 vs day 7 D cells; Mann-Whitney test. (C) Percent CFSElo CD8+ T cell subsets from a healthy donor (HD) and a recipient (R) at day 41 post–haplo-HSCT after PBMC culture with 1 (gray, serving as a nonproliferating control) or 50 ng/mL IL-15 (black) for 8 days. N/D, not detected. (D) Mean ± SEM CFSElo CD8+ T-cell subsets (calculated as in panel C) from healthy donors (n = 6) and haplo-HSCT patients (n = 5). TMEM, CD45RO+ memory T cells. *P < .05, Mann-Whitney test. (E) Combinations of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF production in gated TSCM from patients (n = 3) and in T-cell subsets from healthy donors (HD; n = 4). *P < .05, permutation test.

We next investigated whether the TSCM-phenotype cells observed posttransplant also acquired TSCM functional features, ie, the capability to respond to interleukin-15 (IL-15; for CD8+) and to produce effector cytokines following stimulation with PMA/ionomycin (for both CD4+ and CD8+). These assays allow to differentiate them from “true” TN.13 We first attempted to do this in T cells isolated at day 7. However, the cells failed to survive or were unresponsive in vitro (not shown), presumably due to exposure to immunosuppressive drugs in vivo. Moreover, these cells could not be purified by FACS sorting ex vivo due to their paucity; therefore, bulk PBMC cultures were used. T-cell phenotypes are largely maintained following IL-1513 and PMA/ionomycin treatment (supplemental Figure 7), thus justifying our approach. CD8+ TSCM between day 41 and day 65 post–haplo-HSCT diluted CFSE similarly to CD45RO+ TMEM. Conversely, in line with previous experiments, TN from healthy donors did not (Figure 2C-D). Moreover, TSCM displayed a combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF expression similar to that of naturally occurring TSCM following PMA/ionomycin stimulation but distinct from the functional profiles of TN and TMEM from healthy donors (Figure 2E). This combination is reminiscent of the functionality of TSCM in nonhuman primates.28 Collectively, these data show that T cells with the TSCM phenotype are abundant following pt-Cy and display TSCM functional properties.

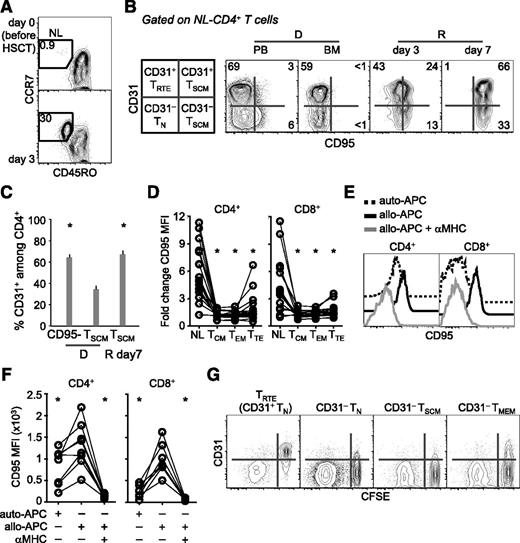

Putative TN-cell origin of posttransplant TSCM

The loss of TN and the accumulation of TSCM at day 7 was unexpected, given the preferential survival of TN, but not of TSCM, to pt-Cy. Moreover, TSCM were almost absent in the graft (Figure 2B). We thus reasoned that posttransplant TSCM-phenotype cells might have derived from transferred TN. To validate this concept, we followed the expression of CD31, a marker preferentially expressed by early-differentiated CD4+ TRTE29 and downregulated in CD4+ TSCM and TMEM.13 CD8+ T cells were not studied in this regard, as CD31 has no phenotypic value in the identification of CD8+ TRTE. Before transplantation (day 0), CD45RO−CCR7+ naive-like (NL; ie, comprising both TN and TSCM) T cells were virtually absent in the PB of the recipient but were detected at day 3 (Figure 3A). Host T cells did not display the NL phenotype at multiple time points (Figure 2A-B and data not shown), thus obviating the need to differentiate between donor and recipient HLA to follow this population of cells. NL-CD4+ T cells from BM were mostly CD95− but progressively acquired CD95 within both the CD31+ and the CD31− fractions (Figure 3B). This shift was independent of pt-Cy, as in vitro mafosfamide treatment did not induce CD95 in FACS-sorted TN (not shown). At day 7, CD95+ TSCM expressed CD31 at frequencies similar to those of the CD95− fraction and higher than those of TSCM from the PB of the related donors (Figure 3B-C). These CD31+CD95+ cells are normally present, although at low frequency, in the PB of healthy donors (Figure 3B), indicating that they are not an artifact of allo-HSCT. Importantly, CD95 expression increased specifically in NL cells between day 3 and day 7 (Figure 3D), thus excluding that CD95 upregulation is a generalized effect of all T cells. Furthermore, in vitro incubation of TN with allo-APCs, but not auto-APCs, led to CD95 upregulation in the nonalloreactive fraction (defined as negative for both CD25 and CD69 activation markers; Figure 3E-F), indicating that acquisition of the TSCM phenotype may occur in the allogeneic environment. Such an increase could be prevented by anti-MHC class II (for CD4+) and class I (for CD8+) blocking antibodies (Figure 3E-F). It could be argued that CD31 is induced by preexisting TSCM upon activation and/or proliferation. To test this possibility, we cocultured FACS-sorted CD31+ TRTE as well as CD31− TN and TMEM (supplemental Figure 8) with allo-APCs to monitor CD31 expression in the proliferating (CFSElo) population. CD31+ TSCM could not be tested due to low recovery. TRTE lost CD31 expression upon CFSE dilution (Figure 3G). Accordingly, CD31− subsets failed to reacquire CD31 (Figure 3G). Collectively, our results suggest that TSCM observed following pt-Cy putatively derive from adoptively transferred TN.

Putative TN-cell origin of posttransplant TSCM. (A) Representative frequency (out of 12) of CD45RO−CCR7+ T cells in a patient a day 0 and day 3 post–haplo-HSCT. (B) Representative (out of 12) CD31 and CD95 expression on NL-CD4+ T cells from the PB and BM of a donor and from the PB of the related recipient at different times post–haplo-HSCT. A scheme with the nomenclature of subsets according to phenotype is depicted on the left. NL, CD45RO−CCR7+. Numbers in plots indicate the percentage of cells in the gates. (C) Mean ± SEM CD31 expression on PB CD4+CD95− cells and CD4+ TSCM from marrow donors (D) and CD4+ TSCM from the related recipients (R; n = 12) at day 7 post–haplo-HSCT. *P < .05 vs D TSCM; Wilcoxon test. (D) Fold change in CD95 median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in different T-cell subsets (n = 19) between day 3 and day 7. *P < .05 vs NL; Wilcoxon-paired test. (E) Representative analysis of CD95 expression by TN cells following incubation with different stimuli. Histograms are referred to the CD25−CD69− nonalloreactive population, as specified in the text. (F) Summary of the data obtained in panel E (n = 8; 4 independent experiments; *P < .05 vs allo-APCs, Wilcoxon-paired test). (G) CFSE dilution and CD31 expression by FACS-sorted T-cell subsets following incubation with allo-APCs for 5 days. D, donor; R, recipient.

Putative TN-cell origin of posttransplant TSCM. (A) Representative frequency (out of 12) of CD45RO−CCR7+ T cells in a patient a day 0 and day 3 post–haplo-HSCT. (B) Representative (out of 12) CD31 and CD95 expression on NL-CD4+ T cells from the PB and BM of a donor and from the PB of the related recipient at different times post–haplo-HSCT. A scheme with the nomenclature of subsets according to phenotype is depicted on the left. NL, CD45RO−CCR7+. Numbers in plots indicate the percentage of cells in the gates. (C) Mean ± SEM CD31 expression on PB CD4+CD95− cells and CD4+ TSCM from marrow donors (D) and CD4+ TSCM from the related recipients (R; n = 12) at day 7 post–haplo-HSCT. *P < .05 vs D TSCM; Wilcoxon test. (D) Fold change in CD95 median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in different T-cell subsets (n = 19) between day 3 and day 7. *P < .05 vs NL; Wilcoxon-paired test. (E) Representative analysis of CD95 expression by TN cells following incubation with different stimuli. Histograms are referred to the CD25−CD69− nonalloreactive population, as specified in the text. (F) Summary of the data obtained in panel E (n = 8; 4 independent experiments; *P < .05 vs allo-APCs, Wilcoxon-paired test). (G) CFSE dilution and CD31 expression by FACS-sorted T-cell subsets following incubation with allo-APCs for 5 days. D, donor; R, recipient.

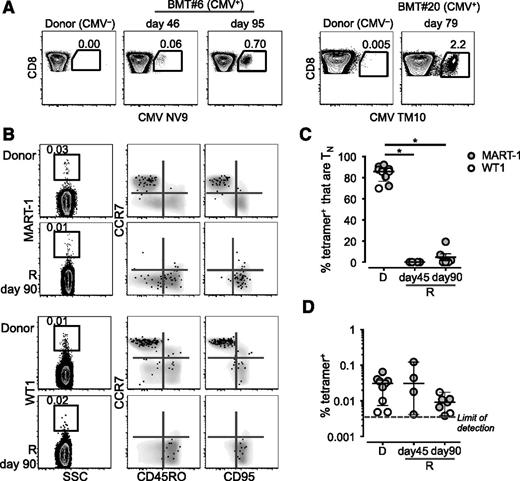

Persistence and memory differentiation of antigen-specific TN

Next, we addressed whether donor TN that survived pt-Cy contribute to reconstitution at the antigen-specific level. We followed the fate of self-/tumor-specific T cells by using MHC class I tetramers. The staining specificity is shown in supplemental Figure 9A. We confined our analysis to ∼90 days post–haplo-HSCT to exclude the generation of new TN by resumed thymic output.10 CD4+ TRTE or TN were absent during this time period (supplemental Figure 3). Accordingly, signal-joint T-cell receptor excision circles (indicative of thymic output) in PB lymphocytes from an independent cohort of patients receiving haplo-HSCT and pt-Cy but myeloablative conditioning were much lower at 3 and 6 months post–haplo-HSCT compared with donor samples (B.B., unpublished observation). Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were present at similar frequencies in the BM and PB of donors (supplemental Figure 9B), as described previously,30 thus justifying the use of PB cells when patient BM was unavailable. Two CMV+ patients receiving CMV− grafts mounted CMV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (Figure 4A), suggesting that CMV reactivation and, thus, activation and depletion of transferred CMV-specific T cells do not occur within 4 days post–haplo-HSCT. These CMV-specific responses are thought to originate from the transferred TN and not from preexisting memory cells, as CD8+ T cells, different from CD4+ T cells,31 were shown to lack pathogen-specific memory T cells in unexposed individuals.32 TN specific for self/tumor antigens, such as MART-1 and WT1, behaved similarly. These specific cells, which are present at relatively high frequencies in healthy individuals,33,34 mostly displayed a TN phenotype in healthy donors (Figure 4B-C). In the recipients, they could be detected up to day 90 post-HSCT (Figure 4D) and acquired a CD45RO+CCR7−CD95+ phenotype (as soon as day 45 post–haplo-HSCT for MART-1), thus suggesting effector/memory differentiation (Figure 4B-C). We conclude that antigen-specific TN survive pt-Cy and participate in immune reconstitution in the lymphopenic host.

Persistence and memory differentiation of antigen-specific TN. (A) Frequency of CD8+ T cells in PBMCs from 2 CMV− donors and matched CMV+ recipients at different time points post–haplo-HSCT. (B) Frequency and phenotype of MART-1– and WT1-specific CD8+ T cells identified by MHC class I tetramers. Tetramer+ T cells are overlaid on top of the total CD8+ T-cell population depicted in gray. In panels A and B, numbers indicate the percentage of cells identified by the gates. (C) Frequency of MART-1+ (filled gray circles) and WT1+ (blank circles) CD8+ T cells with a TN-cell phenotype in donors (D) and recipients (R) at day 45 and day 90 post–haplo-HSCT. P < .05, Mann-Whitney test. (D) Mean ± SEM frequency of the cells identified in panel B.

Persistence and memory differentiation of antigen-specific TN. (A) Frequency of CD8+ T cells in PBMCs from 2 CMV− donors and matched CMV+ recipients at different time points post–haplo-HSCT. (B) Frequency and phenotype of MART-1– and WT1-specific CD8+ T cells identified by MHC class I tetramers. Tetramer+ T cells are overlaid on top of the total CD8+ T-cell population depicted in gray. In panels A and B, numbers indicate the percentage of cells identified by the gates. (C) Frequency of MART-1+ (filled gray circles) and WT1+ (blank circles) CD8+ T cells with a TN-cell phenotype in donors (D) and recipients (R) at day 45 and day 90 post–haplo-HSCT. P < .05, Mann-Whitney test. (D) Mean ± SEM frequency of the cells identified in panel B.

Antigen-specific memory T cells may survive pt-Cy and expand in the host in the presence of the cognate antigen

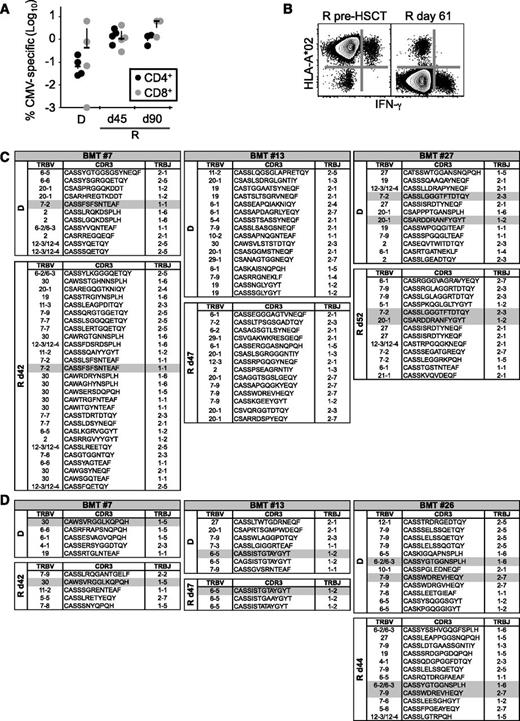

Antigen-specific memory can be transferred with allo-HSCT.35 We sought to test whether persistent antigen in the recipient may render antigen-specific T cells susceptible to pt-Cy, as reported in murine models.36 To this end, we investigated PB CD4+ and CD8+ CMV-specific T cells in donor/recipient pairs who were matched for CMV infection (Figure 5A). These cells were of donor origin, as indicated by the analysis of the mismatched HLA-A*02 (Figure 5B). FACS sorting of the same cells followed by sequencing of the TCRB gene revealed that some CDR3 sequences overlapped between donor and recipients in most of the patients at the amino acid (Figure 5C-D) and nucleotide levels (data not shown) while the majority appeared to be unique, hence corroborating the idea that some antigen-specific T-cell clones may survive pt-Cy and expand in the recipient in the presence of the cognate antigen.

Antigen-specific memory T cells may survive pt-Cy and expand in the host in the presence of the cognate antigen. (A) Frequency of CMV-specific memory T cells in haplo-HSCT recipients (R) at day 45 and day 90 and in related donors (D). (B) Representative analysis of donor-derived CMV-specific T-cell responses detected by simultaneous analysis of the mismatched HLA (in this case the donor was HLA-A*02−) and intracellular IFN-γ following stimulation with CMV pp65 overlapping peptide mix. Plots show Aqua−CD3+ cells. (C-D) TCRB clonal composition of CMV-specific CD4+ (C) and CD8+ (D) T cells in CMV+/+ donor/recipient pairs. Overlapping sequences are highlighted in gray. d, day after haplo-HSCT.

Antigen-specific memory T cells may survive pt-Cy and expand in the host in the presence of the cognate antigen. (A) Frequency of CMV-specific memory T cells in haplo-HSCT recipients (R) at day 45 and day 90 and in related donors (D). (B) Representative analysis of donor-derived CMV-specific T-cell responses detected by simultaneous analysis of the mismatched HLA (in this case the donor was HLA-A*02−) and intracellular IFN-γ following stimulation with CMV pp65 overlapping peptide mix. Plots show Aqua−CD3+ cells. (C-D) TCRB clonal composition of CMV-specific CD4+ (C) and CD8+ (D) T cells in CMV+/+ donor/recipient pairs. Overlapping sequences are highlighted in gray. d, day after haplo-HSCT.

Poor expansion of adoptively transferred memory T cells in the absence of cognate antigen

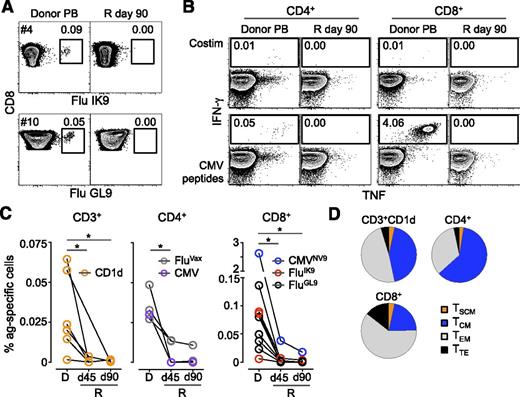

Finally, we determined the extent of reconstitution of adoptively transferred memory T cells in the virtual absence of cognate antigen. Flu-specific memory CD8+ T cells were detectable in the PB and BM of donors, but not in the recipients, up to 90 days post–haplo-HSCT (Figure 6A-C; supplemental Figure 9B). Interestingly, CD3+ natural killer T cells recognizing the α-galactosylceramide analog PBS57 declined as well. The specific cells were Ki-67− at the time of transfer (supplemental Figure 9C). Similarly, adoptively transferred CMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from a CMV+ donor could not be detected in a CMV− recipient (Figure 6B-C), as previously reported.37 Flu-specific CD4+ T cells responding in vitro to the seasonal influenza vaccine (FluVAX) behaved in the same way (Figure 6C). It has been demonstrated that early-differentiated memory T cells better persist and expand in vivo following adoptive transfer.12,35 In our setting, the relative abundance of the different memory T-cell phenotypes did not influence such behaviors (Figure 6D). These results indicate that adoptively transferred memory T cells fail to expand in the blood of recipients in the absence of their cognate antigen.

Poor expansion of adoptively transferred memory T cells in the absence of cognate antigen. (A) MHC class I tetramer identification of CD8+ T cells specific for Flu IK9 and Flu GL9 epitopes in the PB of marrow donors and the related recipients (R) at day 90 post–haplo-HSCT. (B) TNF and IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the haplo-HSCT #10 donor/recipient pair (CMV+ and CMV−, respectively) following in vitro stimulation with CMV pp65 peptide pool. In panels A and B, numbers indicate the percentage of cells identified by the gates. (C) Summary of the frequency of CD3+ natural killer T cells binding CD1d/PBS57 tetramer and Flu and CMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the PB of donor (D) and the related recipients (R) at day (d) 45 and d90 post–haplo-HSCT. *P < .05, Mann-Whitney test. (D) Differentiation phenotypes of the transferred antigen-specific T cells identified in panel C. Data are presented relative to total memory T cells.

Poor expansion of adoptively transferred memory T cells in the absence of cognate antigen. (A) MHC class I tetramer identification of CD8+ T cells specific for Flu IK9 and Flu GL9 epitopes in the PB of marrow donors and the related recipients (R) at day 90 post–haplo-HSCT. (B) TNF and IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the haplo-HSCT #10 donor/recipient pair (CMV+ and CMV−, respectively) following in vitro stimulation with CMV pp65 peptide pool. In panels A and B, numbers indicate the percentage of cells identified by the gates. (C) Summary of the frequency of CD3+ natural killer T cells binding CD1d/PBS57 tetramer and Flu and CMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the PB of donor (D) and the related recipients (R) at day (d) 45 and d90 post–haplo-HSCT. *P < .05, Mann-Whitney test. (D) Differentiation phenotypes of the transferred antigen-specific T cells identified in panel C. Data are presented relative to total memory T cells.

Discussion

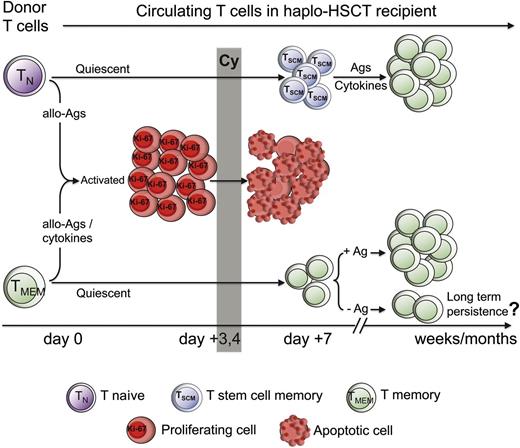

Here, we report the cellular mechanisms responsible for T-cell reconstitution following haplo-HSCT and pt-Cy at the antigen-specific and clonal levels and suggest that “TN-derived TSCM” play a nonredundant role in this regard. A proposed model of the events occurring in this type of HSCT is depicted in Figure 7. Extensive phenotypic and functional analysis of T-cell subsets during the first few days following transplantation revealed that nonalloreactive TN were preferentially spared by pt-Cy because of their delayed activation kinetics. Unexpectedly, TN were outnumbered by TSCM-phenotype cells at day 7, which later displayed TSCM functional properties. Conversely, as much as 70% of memory/effector-phenotype T cells were proliferating by day 3 post–haplo-HSCT and were subsequently depleted by pt-Cy. Experiments performed in mouse models by Mayumi et al showed that pt-Cy failed to block GVHD following transfer of allogeneic donor splenocytes immunized with host T cells 7 days before,8 thus leading to the hypothesis that memory T cells are more resistant to pt-Cy compared with TN.3 However, because day 7 coincides with the effector phase (ie, the peak of T-cell expansion), escape from pt-Cy possibly occurred because of the relative abundance of transferred effectors rather than the acquisition of memory capacity. Our experiments show that both TN and memory T cells divide in response to allogeneic stimulation and that TN rapidly acquire CD45RO, thus indicating that the proliferating memory/effector-phenotype cells observed at day 3 include T cells derived from both compartments (Figure 1).

Proposed model of the cellular mechanisms leading to T-cell reconstitution following haplo-HSCT and pt-Cy. Naive (TN) and memory T cells (TMEM) are infused in the recipient with the BM. Allogeneic antigens (allo-Ags), as well as inflammatory/homeostatic cytokines, the availability of which increases after chemotherapy, induce T-cell activation. Proliferating (HLA-DR+, Ki-67+) T cells uniformly acquire an effector phenotype, irrespective of their original differentiation status, and are preferentially depleted by Cy, given at day 3 and 4 after HSCT. T stem cell memory (TSCM) is the dominant peripheral T-cell subset at day 7, likely originating from TN that survived Cy. In the following weeks, naive-derived TSCM generate memory cells in response to exogenous antigens and, presumably, homeostatic cytokines. Adoptively transferred TMEM, which have survived Cy, expand to detectable levels in the circulation only in the presence of the cognate antigen. Whether T-cell memory can persist in the haplo-HSCT individual in the absence of the cognate antigen is currently unknown.

Proposed model of the cellular mechanisms leading to T-cell reconstitution following haplo-HSCT and pt-Cy. Naive (TN) and memory T cells (TMEM) are infused in the recipient with the BM. Allogeneic antigens (allo-Ags), as well as inflammatory/homeostatic cytokines, the availability of which increases after chemotherapy, induce T-cell activation. Proliferating (HLA-DR+, Ki-67+) T cells uniformly acquire an effector phenotype, irrespective of their original differentiation status, and are preferentially depleted by Cy, given at day 3 and 4 after HSCT. T stem cell memory (TSCM) is the dominant peripheral T-cell subset at day 7, likely originating from TN that survived Cy. In the following weeks, naive-derived TSCM generate memory cells in response to exogenous antigens and, presumably, homeostatic cytokines. Adoptively transferred TMEM, which have survived Cy, expand to detectable levels in the circulation only in the presence of the cognate antigen. Whether T-cell memory can persist in the haplo-HSCT individual in the absence of the cognate antigen is currently unknown.

TSCM-phenotype cells were the dominant donor T cells in the PB following pt-Cy and are thought to derive from donor TN. A weakness of the current study is that this relationship could not be demonstrated directly at the antigen-specific or clonal level due to the low abundance of these cells in vivo. Nevertheless, the experiments shown in Figure 3 support this conclusion. Although only circulating T cells could be tested for ethical reasons, proliferation of preexisting donor TSCM or redistribution from lymphoid tissues seems unlikely, given the depletion of proliferating cells by pt-Cy and the virtual absence of TSCM in the BM, respectively. The frequency of CD45RA+CCR7+ TN (which are closely related to TSCM) in the transfer product positively correlated with CAR+ T-cell expansion in patients with cancer.38 Moreover, IL-7 and IL-15, which are elevated in lymphopenic individuals, favored the generation of TSCM from TN precursors,14 further supporting the conclusion that posttransplant TSCM in haplo-HSCT derive from TN.

The acquisition of memory/effector phenotypes by self-/tumor-specific T cells also suggests that transferred TN progressed through an early TSCM stage (Figure 7). Self-specific memory T cells are rarely observed, unless in pathological conditions. For instance, MART-1–specific memory cells are abundant in metastatic melanoma but rare in healthy donors,13,39 suggesting that high antigen load, costimulation, and local inflammation are required for MART-1–specific T-cell priming.40 Alternatively, the conversion of TN into memory-like cells has been reported to occur in mice in response to lymphopenia (ie, increased levels of homeostatic cytokines).41-44 Whether homeostatic proliferation rather than cognate antigen stimulation is the major mechanism driving the differentiation of self-/tumor-specific TN will require further study.

Although still present after Cy treatment, residual memory T cells displayed a limited reconstitution capacity, at least in the circulation (Figure 6). The presence of the cognate antigen seems to dictate the expansion of antigen-specific memory T cells, as (some) donor clones were detected in CMV-infection–matched transplants. These data, along with those obtained from donor CMV−/recipient CMV+ transplants, imply that reactivation of CMV, and possibly of any other persistent infection, occurs late enough to allow pathogen-specific T cells to escape pt-Cy–mediated depletion, hence promoting the transfer of immunity. Nevertheless, the depletion of some nonalloreactive memory T-cell clones by pt-Cy, caused by their more rapid homeostatic proliferation compared with TN,13,45 cannot be completely ruled out. Whether T-cell memory can persist in these individuals in the relative absence of cognate antigen in body sites other than the circulation remains an open question. The current study could not test this possibility due to ethical reasons.

Collectively, our results shed light on the mechanisms governing pt-Cy function in vivo and suggest that transferred TN may acquire TSCM traits in the lymphopenic environment and subsequently contribute to immune reconstitution. Intriguingly, the abundance of TN in BM correlated with improved overall survival and decreased acute GVHD.46 At the antigen-specific level, pt-Cy allows the generation of primary and memory T-cell responses even in the presence of persistent antigen in the host. We propose to explore the adoptive transfer of large numbers of TN before pt-Cy to favor the generation of TSCM and boost immune reconstitution.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and nurses of the Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplant Unit (Humanitas, Milan) for making this study possible, Margaret Beddall and Pratip Chattopadhyay (Vaccine Research Center, National Insitutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda) for antibody conjugation and validation, Achille Anselmo and Paolo Somma (Flow Cytometry Facility, Humanitas) for help with cell sorting, Joseph P. Casazza (Vaccine Research Center, NIH) for provision of the CMV pp65 peptide pool, Silvia Cena and Roberta Pulito (University of Turin) for assistance with TREC data analysis, and members of the Mavilio Laboratory for critical discussion. The CD1d/PBS57 tetramers were kindly provided by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility.

This work was supported by grants from the Fondazione Cariplo (Grant Ricerca Biomedica 2012/0683 to E.L.), the European Union (Marie Curie Career Integration Grant 322093 to E.L.), and the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (MFAG 10607 to E.L. and IG 14687 to D.M), by the Italian Ministry of Health (Bando Giovani Ricercatori GR-2008-1135082 to D.M. and GR-2011-02347324 to E.L.), as well as funds provided by the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (to M.R.) and Humanitas Intramural Research and Clinical Funding Programs (to D.M. and L.C.). A.R. is a recipient of the Guglielmina Lucatello e Gino Mazzega Fellowship from the Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro. D.A.P. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator.

Authorship

Contribution: A.R., L.C., D.M., and E.L. conceived research; A.R., V.Z., C.C., K.L., J.E.M., and E.L. performed experiments; L.C., S.B., R.C., S.G., B.S., A.S., B.B., C.C.-S., and P.C. performed clinical procedures; P.T. and I.T. provided technical support with sample processing; A.R., V.Z., D.A.P., M.R., D.M., and E.L. analyzed the data; E.G., D.A.P., and M.R. provided reagents; A.R., D.M., and E.L. wrote the manuscript; and all authors edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Domenico Mavilio, Unit of Clinical and Experimental Immunology, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Via Alessandro Manzoni 113, Rozzano, 20089 Milan, Italy; e-mail: domenico.mavilio@humanitas.it; and Enrico Lugli, Unit of Clinical and Experimental Immunology, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Via Alessandro Manzoni 113, Rozzano, 20089 Milan, Italy; e-mail: enrico.lugli@humanitasresearch.it.

References

Author notes

L.C. and V.Z. contributed equally to this study.

D.M. and E.L. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal