Abstract

To understand the placement of a certain protein in a physiological system and the pathogenesis of related disorders, it is not only of interest to determine its function but also important to describe the sequential steps in its life cycle, from synthesis to secretion and ultimately its clearance. von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a particularly intriguing case in this regard because of its important auxiliary roles (both intra- and extracellular) that implicate a wide range of other proteins: its presence is required for the formation and regulated release of endothelial storage organelles, the Weibel-Palade bodies (WPBs), whereas VWF is also a key determinant in the clearance of coagulation factor VIII. Thus, understanding the molecular and cellular basis of the VWF life cycle will help us gain insight into the pathogenesis of von Willebrand disease, design alternative treatment options to prolong the factor VIII half-life, and delineate the role of VWF and coresidents of the WPBs in the prothrombotic and proinflammatory response of endothelial cells. In this review, an update on our current knowledge on VWF biosynthesis, secretion, and clearance is provided and we will discuss how they can be affected by the presence of protein defects.

Introduction

von Willebrand (VW) factor (VWF) is a multimeric glycoprotein present in blood plasma, the subendothelial matrix, as well as storage granules in endothelial cells (Weibel-Palade [WP] bodies [WPBs]) and platelets (α-granules).1 Although a series of novel functional properties of VWF has recently been proposed,2 the protein is mostly known for its contribution to the hemostatic process: it mediates platelet adhesion and aggregation at sites of vascular injury and carries coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) in the circulation.1 Patients lacking VWF manifest a severe hemorrhagic phenotype, originating from defective formation of platelet-rich thrombi and a secondary deficiency of FVIII impairing the generation of a fibrin network. Functional and/or quantitative deficiencies of VWF are known as von Willebrand disease (VWD), a disorder affecting 0.01% to 1% of the population.3 Quantitative deficiencies of VWF result from changes in biosynthesis, secretion, and/or clearance of the protein. In this review, we will provide an overview of the current knowledge on each of these processes and we will discuss how they can be affected by the presence of protein defects.

Part I: Basics of VWF biosynthesis

Primary structure

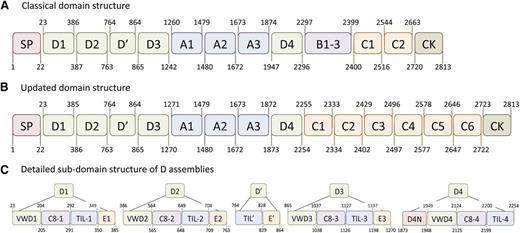

VWF is produced in endothelial cells and megakaryocytes as a single prepropolypeptide of 2813 aa. The primary sequence of VWF was reported in 1986, and rapidly the presence of repeating domain structures within the protein was recognized.4 The different domains are arranged in the order: D1-D2-D′-D3-A1-A2-A3-D4-B1-B2-B3-C1-C2-CK, with the D1-D2 domains representing the propeptide and the remainder corresponding to the mature VWF subunit (Figure 1).4-6 Progress in structural and bioinformatical analysis of protein structures has recently led to a reassessment of the mosaic architecture of VWF, proposing the following domain structure (Figure 1): D1-D2-D′-D3-A1-A2-A3-D4-C1-C2-C3-C4-C5-C6-CK.4-6 This analysis revealed that the D domains consist of various distinct structures: the D1, D2, and D3 domains each contain a VW domain, a C8 fold, a trypsin inhibitor-like (TIL) structure, and an E module. The VWF domain and C8 fold are both absent in the D′ domain, whereas the D4 domain lacks the E module, but contains a unique subdomain, designated D4N.5 Another important change relates to the C-terminal part of the protein, in which the B-C-domain region is replaced by 6 consecutive C domains.5

Schematic representation of the old and new domain arrangement of VWF. The molecular architecture of VWF is characterized by the presence of distinct domain structures. (A) The arrangement of 5 different domain structures according to the original analysis of the VWF sequence (reviewed by Pannekoek and Voorberg).4 The numbering of the domain boundaries has been used in our laboratory in previous years. (B) The domain organization as has been recently proposed by Zhou et al.5 One striking difference with the original domain structure is the replacement of the B1-3-C1-C2 domain region by 6 homologous C domains. In addition, their analysis revealed that the D domains consist of various independent structures, which are highlighted in panel (C). The D1, D2, and D3 domains each contain a VW domain, a trypsin inhibitor-like structure, a C8 fold, and an E module. The D′ region lacks the VW domain and C8 fold. The D4 domain lacks the E module, but instead comprises a unique sequence designated D4N. Adapted from Rauch et al6 with permission.

Schematic representation of the old and new domain arrangement of VWF. The molecular architecture of VWF is characterized by the presence of distinct domain structures. (A) The arrangement of 5 different domain structures according to the original analysis of the VWF sequence (reviewed by Pannekoek and Voorberg).4 The numbering of the domain boundaries has been used in our laboratory in previous years. (B) The domain organization as has been recently proposed by Zhou et al.5 One striking difference with the original domain structure is the replacement of the B1-3-C1-C2 domain region by 6 homologous C domains. In addition, their analysis revealed that the D domains consist of various independent structures, which are highlighted in panel (C). The D1, D2, and D3 domains each contain a VW domain, a trypsin inhibitor-like structure, a C8 fold, and an E module. The D′ region lacks the VW domain and C8 fold. The D4 domain lacks the E module, but instead comprises a unique sequence designated D4N. Adapted from Rauch et al6 with permission.

Disulfide bridging

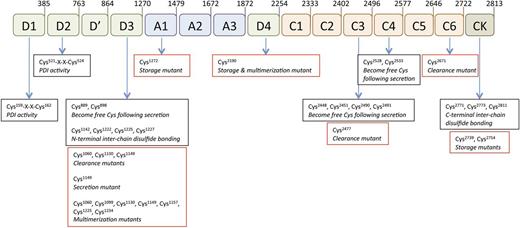

The VWF sequence contains an unusually high content of cysteine residues (8.3%), a percentage fourfold higher than the average in human proteins.7 Concerning the incorporation of these Cys residues in disulfide bridging, there have been apparent contradictory observations. Some reports indicate that there are no or little free thiols present in VWF.8,9 In contrast, mass spectrometrical analysis of purified plasma-derived or recombinant VWF revealed the presence of several unpaired cysteines (positions 889, 898, 2448, 2451, 2453, 2490, 2491, 2528, and 2533; Figure 2).1,7,10-18 A recent study by Shapiro et al revealed that these apparently free cysteines are essential for proper folding and secretion of the protein.7 In their model, all cysteines participate in disulfide bonding but they do so in a sequential manner during biosynthesis. Furthermore, some of these pairs are sensitive to disulfide reduction and could therefore be converted into free thiols once secreted. Such flexibility would allow VWF to use the oxidation state of the cysteines to modify its functional properties.19

Overview of relevant cysteine residues in VWF. The VWF protein sequence contains 234 cysteine residues, representing 8.3% of the total amino acid composition, a number that is fourfold higher than the average in human proteins. Cysteines contribute to the folding of the domains that characterize the VWF structure. Some of these cysteines form disulfide bridges during synthesis, but are susceptible to reduction following secretion. Consequently, they are converted into free thiols (positions 889, 898, 2448, 2451, 2453, 2490, 2491, 2528, and 2533).7,10 Other cysteines engage in intersubunit disulfide bonding (positions 2771, 2773, and 2811 in the CK domain and positions 1142, 1222, 1225, and 1227 in the D3 domain).1,11,12 N-terminal multimerization involves disulfide isomerase activity located in the D1 and D2 domains (motif 159-162 and 521-524).13 Given their importance for the VWF structure, it is not surprising that mutations of cysteines may affect different stages of the VWF life cycle. Examples hereof (red boxes) include mutations affecting multimerization, storage in WPBs, secretion, and clearance.14-18

Overview of relevant cysteine residues in VWF. The VWF protein sequence contains 234 cysteine residues, representing 8.3% of the total amino acid composition, a number that is fourfold higher than the average in human proteins. Cysteines contribute to the folding of the domains that characterize the VWF structure. Some of these cysteines form disulfide bridges during synthesis, but are susceptible to reduction following secretion. Consequently, they are converted into free thiols (positions 889, 898, 2448, 2451, 2453, 2490, 2491, 2528, and 2533).7,10 Other cysteines engage in intersubunit disulfide bonding (positions 2771, 2773, and 2811 in the CK domain and positions 1142, 1222, 1225, and 1227 in the D3 domain).1,11,12 N-terminal multimerization involves disulfide isomerase activity located in the D1 and D2 domains (motif 159-162 and 521-524).13 Given their importance for the VWF structure, it is not surprising that mutations of cysteines may affect different stages of the VWF life cycle. Examples hereof (red boxes) include mutations affecting multimerization, storage in WPBs, secretion, and clearance.14-18

Multimerization

The pairing of cysteines within VWF is not limited to a single subunit. During synthesis, 2 pro-VWF subunits first engage into a covalent connection, involving the formation of 3 interchain cysteine pairs located in the C-terminal cysteine knot (CK) domains.11 Importantly, the structural location of these 3 intermolecular pairs protects them from disulfide reduction, ensuring the long-term stability of the dimeric conformation of VWF.12 Second, pro-VWF dimers are linked covalently via interchain disulfide bridging involving cysteines of the D3 domain. For this process, the presence of the propeptide (D1-D2 domains) and D′ domain is crucial for 2 reasons. First, the propeptide and D′ domain serve to properly align the pro-VWF dimers, thereby facilitating D3 domain-mediated interdimeric cross-linking (“zipper model”). Second, the propeptide may catalyze disulfide formation between D3 domains via its protein disulfide isomerase activity, which locates to the CxxC motifs at positions 159-162 and 521-524.13 It is noteworthy that the propeptide does not need to be attached to the D′D3 region to exert its cross-linking activity, as expression of the propeptide in trans proved sufficient to support VWF multimerization.20 The propeptide is indeed able to bind to the D′-D3 region, particularly under conditions found in the cellular environment (low pH, low NaCl, high CaCl2).21,22 The multimerization process generates a heterogeneous pool of differentially sized multimers that contain between 2 and >60 subunits.1,23

Glycosylation

During synthesis, VWF is subject to various posttranslational modifications, including furin-mediated separation of the propeptide and glycosylation. Crucial to the VWF life cycle, glycosylation starts in the early phase of synthesis. Indeed, within the endoplasmic reticulum, the enzyme oligosaccharyltransferase mediates the attachment of a core 14-saccharide unit to asparagine residues within the developing polypeptide chain. Different studies revealed that the pro-VWF subunit carries 17 N-linked carbohydrate structures: 4 being located in the propeptide and 13 within the mature subunit.24-26 Further along the synthesis pathway, the N-linked glycans undergo maturation, whereas 10 O-linked glycans are also added.27,28 Detailed analysis of VWF by various groups unveiled an immense variation among these carbohydrate structures, particularly among the N-linked glycans (>300 structures identified). A number of interesting features are worth highlighting:

(1) Sialylation.

(2) Sulfation.

Five sites for N-linked glycans (p.Asn1515, p.Asn2223, p.Asn2290, p.Asn2400, and p.Asn2790) are preceded by Pro-Xxx-Arg/Lys/His motifs, favoring terminal sulfation. Metabolic labeling and mass spectrometrical analysis have confirmed the presence of sulfated glycan residues in VWF.26,29 The functional importance of these sulfated residues remains to be elucidated.

(3) Blood group determinants.

Both N- and O-linked glycans can carry ABO(H) blood group carbohydrate determinants.25,26,28 These determinants are present on the glycans of the mature subunit but not on those of the propeptide. It is estimated that ∼13% of the N-linked glycans (ie, 1-2 per subunit) and 1% of the O-linked glycans (ie, 1 per 10 subunit) harbor these blood group determinants.

Another point of interest is the different glycosylation pattern described for endothelial and platelet VWF. Platelet VWF contains about 50% fewer sialic acids and lacks the blood group A-antigen and B-antigen structures, whereas the H-antigen is normally present.30

Part II: Basics of VWF storage and secretion

Storage-granule formation

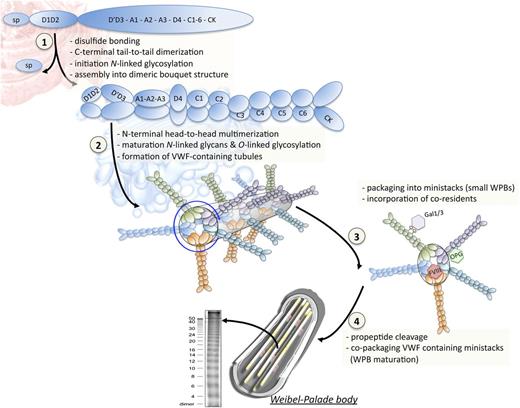

Following synthesis, VWF is transported to storage organelles in both megakaryocytes/platelets (α-granules) and endothelial cells (WPBs).31,32 WPBs and α-granules differ from each other in their dependency on VWF for their formation: α-granules can form in the absence of VWF, whereas the generation of WPBs is strictly VWF dependent.33,34 Given this VWF dependency, we will focus on the formation of WPBs rather than α-granules in the remainder of this paragraph (Figure 3).

Biosynthesis and packaging of VWF in WPBs. The biosynthesis of VWF distinguishes a series of sequential steps that ultimately lead to its incorporation into endothelial storage organelles, the WPBs. (Step 1) During synthesis of the VWF propolypeptide chain in the endoplasmic reticulum, intraprotein cysteine bonding occurs to facilitate folding of the individual domains. Subsequent tail-to-tail interprotein disulfide bridge formation involving the C-terminal CK domains allows the formation of prodimers. Furthermore, the first building blocks for N-linked glycosylation are coupled to the growing polypeptide chain. (Step 2) Upon arrival in the Golgi apparatus, the presence of a slightly acidic pH and relatively high Ca2+ concentration promote the organization of the prodimers into a dimeric bouquet structure, in which the dimers are aligned into a side-by-side manner. Moreover, this environment favors multimerization via disulfide bridging that couples adjacent N-terminal D3 domains, a process that is catalyzed by the propeptide. While the multimerization process takes place, the expanding multimer organizes into a right-handed helical structure, allowing 100-fold compaction of the protein. In this helical structure, the propeptide (D1-D2 domains) and the D′-D3 domains form the wall of the hollow tube. The remainder of the VWF protein (A1-CK domains) protrudes outward from the helical architecture, occupying the space between the tubules that characterize the electron-microscopic images of WPBs. VWF tubules assemble into so-called ministacks that represent the first WPB-like structure. During the passage of VWF through the Golgi, maturation of the N-linked glycans proceeds while O-linked carbohydrate structures are also added to the protein. (Step 3) An important gap in our knowledge of WPB formation is the location of the proteins that coreside with VWF in this organelle. For example, FVIII is known to interact with the D′D3 region, suggesting that FVIII may locate to the inner core of the helix. In contrast, osteoprotegerin (which binds to the A1 domain) and galectins-1 and -3 (which bind to VWF glycans) are more likely to be present in the intertubular space. (Step 4) In the Trans-Golgi network, copackaging of VWF-containing ministacks promotes maturation and formation of larger WPBs. In addition, furin mediates the proteolytic separation of the propeptide from the mature VWF subunits. Of note, under the slightly acidic conditions present within the Trans-Golgi network, the propeptide remains associated with mature VWF. Multimer analysis of endothelial VWF has revealed the presence of very large VWF multimers that exceed the size of multimers found in plasma.

Biosynthesis and packaging of VWF in WPBs. The biosynthesis of VWF distinguishes a series of sequential steps that ultimately lead to its incorporation into endothelial storage organelles, the WPBs. (Step 1) During synthesis of the VWF propolypeptide chain in the endoplasmic reticulum, intraprotein cysteine bonding occurs to facilitate folding of the individual domains. Subsequent tail-to-tail interprotein disulfide bridge formation involving the C-terminal CK domains allows the formation of prodimers. Furthermore, the first building blocks for N-linked glycosylation are coupled to the growing polypeptide chain. (Step 2) Upon arrival in the Golgi apparatus, the presence of a slightly acidic pH and relatively high Ca2+ concentration promote the organization of the prodimers into a dimeric bouquet structure, in which the dimers are aligned into a side-by-side manner. Moreover, this environment favors multimerization via disulfide bridging that couples adjacent N-terminal D3 domains, a process that is catalyzed by the propeptide. While the multimerization process takes place, the expanding multimer organizes into a right-handed helical structure, allowing 100-fold compaction of the protein. In this helical structure, the propeptide (D1-D2 domains) and the D′-D3 domains form the wall of the hollow tube. The remainder of the VWF protein (A1-CK domains) protrudes outward from the helical architecture, occupying the space between the tubules that characterize the electron-microscopic images of WPBs. VWF tubules assemble into so-called ministacks that represent the first WPB-like structure. During the passage of VWF through the Golgi, maturation of the N-linked glycans proceeds while O-linked carbohydrate structures are also added to the protein. (Step 3) An important gap in our knowledge of WPB formation is the location of the proteins that coreside with VWF in this organelle. For example, FVIII is known to interact with the D′D3 region, suggesting that FVIII may locate to the inner core of the helix. In contrast, osteoprotegerin (which binds to the A1 domain) and galectins-1 and -3 (which bind to VWF glycans) are more likely to be present in the intertubular space. (Step 4) In the Trans-Golgi network, copackaging of VWF-containing ministacks promotes maturation and formation of larger WPBs. In addition, furin mediates the proteolytic separation of the propeptide from the mature VWF subunits. Of note, under the slightly acidic conditions present within the Trans-Golgi network, the propeptide remains associated with mature VWF. Multimer analysis of endothelial VWF has revealed the presence of very large VWF multimers that exceed the size of multimers found in plasma.

Although the field is in constant evolution, our understanding of how WPBs are formed and how VWF is packed in these organelles has dramatically improved recently, thanks to the newest electron microscopical imaging techniques (for reviews, see Valentijn and Eikenboom14 and Valentijn et al35 ). Whether the process of WPB formation initiates in the Golgi apparatus or the Trans-Golgi network is still a matter of debate. What is generally accepted is that organelle formation requires VWF multimers to be assembled into a helicoidal structure or tubule (see next paragraph), a step that allows a 100-fold compaction of VWF. In a very elegant study, the Cutler group recently demonstrated that the basic size of the future organelle is already predetermined in the Golgi.36 Indeed, in this compartment, the size of the VWF structure, whether already organized in tubules or not, cannot exceed the size of the Golgi-ribbon structural subunit or ministack, that is, 0.5 μm, leading to the notion of a “length unit.” Later on, in the continuous lumen of the Trans-Golgi network, the VWF cargo originating from different ministacks can be copackaged together into forming organelles that will lead to WPBs of sizes varying from 0.5 to 5 μm (with sizes incrementing by 0.5 μm).36 At this step, the VWF tubules induce membrane protrusions from the Trans-Golgi network, leading to vesicles budding off and formation of immature WPBs.36,37 Another aspect of WPB formation that has been reported relates to the possibility of homotypic fusion of immature WPBs, a process that could contribute to their heterogeneity.37

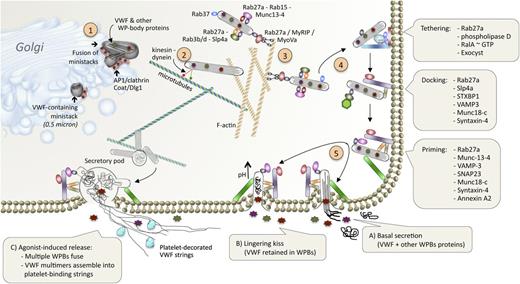

At the molecular level, a number of players have been identified, many of them being involved in classical secretory granule formation. For VWF packaging into nascent organelles, a clathrin coat, the adaptor protein AP-1 and Discs Large-1 (Dlg1), appear necessary, probably to provide a scaffold and generate the typical rod-shaped or cigar-like structure of the WPBs (Figure 4).14,38-42 In this regard, it should also be noted that electron tomography analysis has shown that some of the WP tubules deviate from the rod-shaped structure in that they are twisted or truncated.37,43 Finally, after being released from the Trans-Golgi network, WPBs undergo a maturation step while being anchored on filamentous actin via a triple protein complex containing Rab27a, myosin and Rab27a-interaction protein (MyRIP), and myosin Va (MyoVa).44

Schematic representation of VWF secretion from endothelial cells. Following its synthesis and packaging in WPBs, VWF follows a complex pathway allowing intraendothelial storage combined with basal and regulated secretion. In recent years, many aspects of the molecular machinery that regulate these processes have been identified and this figure provides a schematic overview of the essential elements. (Step 1) The formation of VWF-containing ministacks and subsequent WPBs requires the presence of clathrin coat, the adaptor protein AP-1 and Dlg1. (Step 2) WPBs move around randomly within the endothelial cell along microtubules driven by a so-far-unidentified kinesin/dynein complex. (Step 3) Subsequently, WPBs adhere onto the filamentous actin network via a triple protein complex involving Rab27a, MyoVa, and MyRIP. WPBs also attract a series of other proteins involved in the secretory machinery, including Rab3, Rab15, Rab27a, Rab37, Munc13-4, and Slp4a. (Step 4) Secretion of the WPB content is preceded by sequential steps of tethering, docking, and priming before fusion with the cellular membrane. Specific protein complexes are involved in each of these steps (see boxes). (Step 5) Three types of secretion can be distinguished: (A) basal secretion, in which a single WPB fuses to the cellular membrane and releases its contents (both VWF and other WPB proteins). (B) On rare occasions, exposure to the extracellular environment causes a rapid deacidification of the organelle provoking the pH-dependent tubular VWF structure to collapse. Consequently, VWF is retained within the remainder of the WPB, whereas other WPB proteins (such as interleukin-8) are secreted into the circulation. This process is referred to as a lingering kiss. (C) Upon agonist-induced endothelial stimulation, multiple WPBs aggregate and might eventually fuse into a large secretory vesicle, referred to as secretory pods. This results in the release of massive amounts of VWF multimers. These multimers assemble into the long bundles (up to several hundred μm) that consist of multiple multimers. These bundles are highly thrombogenic as they efficiently recruit platelets. To reduce the thrombogenic potential of the platelet-decorated VWF strings, the action of ADAMTS13 (and also of plasmin under certain conditions) is required. This figure has been inspired by figures presented elsewhere.14,38,39

Schematic representation of VWF secretion from endothelial cells. Following its synthesis and packaging in WPBs, VWF follows a complex pathway allowing intraendothelial storage combined with basal and regulated secretion. In recent years, many aspects of the molecular machinery that regulate these processes have been identified and this figure provides a schematic overview of the essential elements. (Step 1) The formation of VWF-containing ministacks and subsequent WPBs requires the presence of clathrin coat, the adaptor protein AP-1 and Dlg1. (Step 2) WPBs move around randomly within the endothelial cell along microtubules driven by a so-far-unidentified kinesin/dynein complex. (Step 3) Subsequently, WPBs adhere onto the filamentous actin network via a triple protein complex involving Rab27a, MyoVa, and MyRIP. WPBs also attract a series of other proteins involved in the secretory machinery, including Rab3, Rab15, Rab27a, Rab37, Munc13-4, and Slp4a. (Step 4) Secretion of the WPB content is preceded by sequential steps of tethering, docking, and priming before fusion with the cellular membrane. Specific protein complexes are involved in each of these steps (see boxes). (Step 5) Three types of secretion can be distinguished: (A) basal secretion, in which a single WPB fuses to the cellular membrane and releases its contents (both VWF and other WPB proteins). (B) On rare occasions, exposure to the extracellular environment causes a rapid deacidification of the organelle provoking the pH-dependent tubular VWF structure to collapse. Consequently, VWF is retained within the remainder of the WPB, whereas other WPB proteins (such as interleukin-8) are secreted into the circulation. This process is referred to as a lingering kiss. (C) Upon agonist-induced endothelial stimulation, multiple WPBs aggregate and might eventually fuse into a large secretory vesicle, referred to as secretory pods. This results in the release of massive amounts of VWF multimers. These multimers assemble into the long bundles (up to several hundred μm) that consist of multiple multimers. These bundles are highly thrombogenic as they efficiently recruit platelets. To reduce the thrombogenic potential of the platelet-decorated VWF strings, the action of ADAMTS13 (and also of plasmin under certain conditions) is required. This figure has been inspired by figures presented elsewhere.14,38,39

VWF packaging in WPBs

The tubular structure of WPBs is a reflection of how VWF is folded in these organelles. The slightly acidic environment in the WPBs favors self-assembly of VWF subunits via intermolecular interactions within the propeptide/D′-D3 domains.45 This self-assembly results in the formation of long right-handed helical tubules, the interior of which comprises the propeptide/D′-D3 domains.45 The remainder of the protein (ie, the A1-CK region) sticks out of this helical architecture and determines the regular spacing between the helical tubules that are characteristic of the WPBs. Recent work from the Springer group has shown that under acidic conditions the dimeric A1-CK region folds into an intertwined bouquet-like structure, with the domains being aligned in a side-by-side manner.46

Insight into the packaging organization of VWF in the WPBs is not only of relevance to explain the typical morphology of these organelles, but may also be helpful in future studies to explain how WPB coresidents are incorporated. Indeed, many other proteins, mostly involved in inflammation or hemostasis, have been identified in the WPBs besides VWF and its propeptide, such as P-selectin, interleukin-8, osteoprotegerin, angiopoietin-2, and in a selected subset of endothelial cells also FVIII.47-49 Incorporation of some of these residents (like interleukin-8 and tissue-type plasminogen activator) results from a random inclusion process.50 In contrast, other coresidents like P-selectin, galectins, and osteoprotegerin have been shown to directly interact with VWF, which may facilitate their targeting to the WPBs.51-53 Interestingly, except VWF, WPBs do not all contain the same cargo, a feature that also seems to be true for platelet α-granules.54,55 Furthermore, the presence of some coresidents can potentially alter the process of WPB formation. Elegant work by the Mertens/Voorberg group revealed that both the shape and length of the WPBs is dramatically affected by the presence of FVIII: disturbance in the tubular structure leads to round or pear-shaped granules instead of the usual rod-shaped appearance.56 How WPB proteins modulate the well-defined VWF-driven helical tubular structure is an enigma that deserves to be solved in order to better understand how VWF regulates the storage and secretion of these coresidents.

Basal and regulated secretion of VWF

Whereas α-granules release VWF predominantly upon platelet activation, endothelial cells combine basal and regulated release of WPB contents. A number of studies have tried to elucidate the mechanism by which VWF is released from endothelial cells and how the balance between basal and regulated release of VWF is determined; only a brief summary will be provided here (for review, see Nightingale and Cutler38 and Rondaij et al47 ).

There have been opposite views as to whether the majority of VWF released from endothelial cells originates from constitutive or regulated secretory pathways.57,58 However, it is fair to say that the currently accepted view is that VWF is mostly released constitutively from WPBs (Figure 4).14,38,39,59 When present in the endothelial cytoplasm, WPBs dance around in an undirected manner.60 Such movements will eventually drive single WPBs to the cellular periphery, allowing them to fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents into the extracellular space (blood or subendothelium). Circulating VWF mostly originates from this random fusion mechanism. However, in some instances, fusion of WPBs with the plasma membrane results in the selective release of WPB coresidents (interleukin-8, eotaxin-3), whereas VWF and its propeptide are retained within the cell (Figure 4).14,38,39,61 This unexpected observation (referred to as “lingering kiss”) can be explained by a sudden rise in pH of the WPB (deacidification) due to exposure to the extracellular environment.61 This deacidification provokes a collapse of the pH-dependent tubular structure of the WPBs, thereby deforming the VWF-dependent helical structure and preventing secretion of VWF.

Basal release of single WPBs is probably insufficient to produce the long endothelial cell-anchored VWF bundles that recruit platelets, as such strings are only observed upon endothelial stimulation in vitro and in vivo.62,63 Massive release of WPBs is indeed part of the multiple reactions occurring upon endothelial stimulation. From a macroscopic point of view, 3 steps can be distinguished: (1) WPBs center to the perinuclear area, an event that is more or less pronounced, depending on the stimulation trigger60 ; (2) The formation of VWF-enriched patches is observed, probably representing fusion of multiple WPBs and forming a secretory pod60,64 ; (3) Bundles of assembled VWF multimers are released. These bundles are highly prothrombotic in that they efficiently promote platelet adhesion.62,63

At the molecular level, the exocytosis process appears as a complex multistep process and only part of the essential players involved in the sequential steps (tethering, docking, priming, and fusion) have been identified. Among these, the implication of a series of intracellular proteins (including but not limited to: RalA, Rab3, Rab27a, Rab15, Rab33a, Rab37, Munc13-4, Munc18c, Slp4a, Annexin A2-S100A10, syntaxin-binding protein 1, syntaxin-4, VAMP-3, G proteins) has been documented based on the finding that deletion or mutation of these proteins modulates constitutive and/or regulated release of VWF.44,65-73

Recently, an unexpected and novel type of regulation of VWF release has been reported by Torisu and colleagues.74 Not only did they observe that WPBs are often in close proximity of autophagosomes but they also detected the presence of VWF in these organelles.74 In vitro or in vivo inhibition of autophagy led to decreased WPB release, evidenced by lower basal levels of VWF, a lower response to epinephrine-induced WPB release, and a reduction in high-molecular-weight multimers combined with an increased bleeding time in mice. This new set of information thus suggests that VWF release is a combined process involving WPBs and autophagosomes, and follow-up studies aiming to understand how both types of organelles collaborate in this exocytosis process are required.

Part III: Basics of VWF clearance

VWF clearance

Following its release in the circulation, VWF is ready to function as molecular carrier (ie, for FVIII, osteoprotegerin, galectins, and several other proteins) and recruiter of platelets upon vascular injury. However, VWF is similar to other plasma proteins in that its circulatory lifespan is limited. Plasma proteins are sensitive to physical changes (oxidation, proteolysis, glycation, etc), which may alter their functional properties; regulatory mechanisms are in place to eliminate “old” plasma proteins from the circulation. These mechanisms may be unique to each protein, dependent on the need for protein renewal in the circulation.

Following application of therapeutic plasma-derived VWF concentrates, the half-life of VWF antigen in humans is ∼16 hours.75-77 These therapeutic preparations are prepared from large plasma pools, and are thus not representative of the circulatory half-life of VWF in individuals. Indeed, when analyzing the half-life of endogenous VWF following desmopressin treatment, a large variation is observed between individuals, ranging from 4.2 to 26 hours.78,79 The main determinant for this interindividual variation most likely originates from different glycosylation patterns. In particular, the presence of blood group ABO(H) structures appears to explain a large portion of this variation. Individuals with blood group non-O display a longer VWF half-life after desmopressin treatment than individuals with blood group O, which may explain the average 25% higher VWF levels in individuals with blood group non-O.80,81

This interindividual variation may also explain the large variation in the half-life of FVIII in hemophilia A patients.82 VWF functions as a carrier protein for FVIII and therefore FVIII half-life may vary with the individual VWF half-life of the patient. This possibility is supported by the notion that FVIII half-life is dependent on blood group and correlates with preinfusion VWF antigen levels.83-85 Moreover, FVIII half-life can be accurately predicted for each patient using an algorithm based on blood group and preinfusion levels of VWF and of VWF propeptide.85

Cellular basis of VWF clearance

Our knowledge on the mechanism by which VWF is eliminated from the circulation is predominantly based on cellular and murine models. The use of Vwf-deficient mice first allowed the identification of tissues that are responsible for the clearance of VWF. The indication that the majority of VWF is targeted to the liver indicated that VWF is cleared via an active regulatory mechanism rather than via passive elimination.22 Interestingly, when taking into account the size of the different organs, the spleen appeared as efficient as the liver in taking up VWF.86 In order to identify cells that are involved in VWF clearance, immunohistochemical analyses of liver and spleen were analyzed, revealing that VWF principally colocalizes with macrophages (Figure 5).86,87 This colocalization was confirmed in alternative experiments in which the chemical depletion of macrophages resulted in increased VWF survival and elevated levels of endogenous VWF.86,88 Finally, experiments using human macrophages (primary or THP-1–derived) established that VWF is bound and endocytosed by macrophages.86,88,89 The finding that macrophages play an important role in the basal clearance of VWF does not exclude the participation of other nonmacrophage cells in this process.

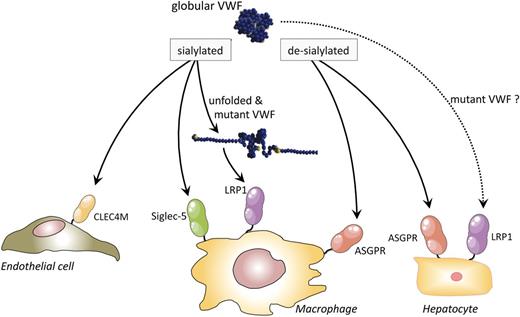

Potential clearance pathways for VWF. VWF circulates as a globular protein, with the majority of its glycan structures being well sialylated. In this form, VWF is recognized by 2 different receptors that could mediate the removal of VWF from the circulation: CLEC4M on endothelial cells and Siglec-5 on macrophages. Shear stress-induced unfolding of VWF is associated with the exposure of interactive site(s) for LRP1. Indeed, in vitro and in vivo experiments have confirmed the involvement of LRP1 in the uptake of VWF in macrophages. Certain VWD-related mutations (eg, the VWD-type 1 Vicenza mutation p.R1205H and the VWD-type 2B mutations p.R1306Q and p.V1316M) provoke exposure of LRP1-interactive sites in the absence of shear stress, which could perhaps explain the accelerated clearance of these mutants. It is unknown whether binding of mutant VWF is limited to macrophage LRP1 (as seems to be the case for wt-VWF) or whether interactions also include LRP1 on other cell types, like hepatocytes or even other as-yet-unidentified receptors. Desialylation of VWF exposes terminal galactose residues, allowing efficient interaction with the ASGPR on macrophages and hepatocytes. Of note, the clearance receptors responsible for the discordant clearance of blood group O and non-O VWF have not been identified yet. ASGPR, asialoglycoprotein receptor. Reprinted from Casari et al87 with permission.

Potential clearance pathways for VWF. VWF circulates as a globular protein, with the majority of its glycan structures being well sialylated. In this form, VWF is recognized by 2 different receptors that could mediate the removal of VWF from the circulation: CLEC4M on endothelial cells and Siglec-5 on macrophages. Shear stress-induced unfolding of VWF is associated with the exposure of interactive site(s) for LRP1. Indeed, in vitro and in vivo experiments have confirmed the involvement of LRP1 in the uptake of VWF in macrophages. Certain VWD-related mutations (eg, the VWD-type 1 Vicenza mutation p.R1205H and the VWD-type 2B mutations p.R1306Q and p.V1316M) provoke exposure of LRP1-interactive sites in the absence of shear stress, which could perhaps explain the accelerated clearance of these mutants. It is unknown whether binding of mutant VWF is limited to macrophage LRP1 (as seems to be the case for wt-VWF) or whether interactions also include LRP1 on other cell types, like hepatocytes or even other as-yet-unidentified receptors. Desialylation of VWF exposes terminal galactose residues, allowing efficient interaction with the ASGPR on macrophages and hepatocytes. Of note, the clearance receptors responsible for the discordant clearance of blood group O and non-O VWF have not been identified yet. ASGPR, asialoglycoprotein receptor. Reprinted from Casari et al87 with permission.

Molecular basis of VWF clearance

The identification of macrophages as VWF-eliminating cells prompted us to examine how VWF uptake was mediated. Macrophages may internalize proteins randomly via receptor-independent macropinocytosis, but it is unclear whether this is also true for VWF. In contrast, a number of receptors have been identified that interact with VWF, indicating that receptor-mediated endocytosis of VWF plays an important role in this regard (Figure 5).87

The first VWF receptor that was identified is the asialoglycoprotein receptor, also known as the Ashwell receptor.90 However, because the majority of the VWF glycans are sialylated, this receptor is not expected to play a major role in the regular clearance process of VWF. Rather, its relevance could become apparent when VWF molecules are hyposialylated, for instance upon pathogen infection or upon reduced activity of sialyltransferase enzymes.90,91

A second receptor recently identified is the lipoprotein receptor LRP1, which was previously identified as a receptor for FVIII.89,92-94 Importantly, VWF binds to LRP1 only when exposed to shear stress, thereby mimicking the flow dependency of the VWF-platelet interaction.89,92 Indeed, VWF needs to unfold in order to be recognized by this receptor, although lower shear forces are needed compared with VWF-platelet interactions. The physiological relevance of macrophage LRP1 in basal VWF clearance is illustrated by the increased endogenous VWF levels and increased survival of VWF in mice that are selectively deficient for LRP1 in macrophages.92 In addition, polymorphisms in the LRP1 gene are associated with VWF plasma levels.95,96

A third potential receptor is Siglec-5, a receptor present on macrophages that specifically interacts with sialic acid residues.97 Although overexpression of Siglec-5 in mouse liver reduces VWF levels, its relevance in the clearance pathways of VWF remains uncertain.

Finally, the Lillicrap group identified CLEC4M as a receptor for VWF.98 Interestingly, genome-wide association studies had previously identified the CLEC4M gene as a determinant of VWF plasma levels, pointing to a physiologically relevant relation between CLEC4M and VWF.99 However, whether CLEC4M modulates VWF clearance or affects VWF levels via an alternative mechanism remains to be determined. It should further be noted that CLEC4M is selectively expressed on sinusoidal endothelial cells, suggesting a potential role for these cells in VWF removal from the circulation.

Taken together, several potential VWF receptors have been identified, but so far only LRP1 appears to play a significant role in basal clearance of VWF. Because LRP1 deficiency prolongs VWF half-life not more than twofold, it seems conceivable that other, so-far-unidentified receptors contribute to VWF clearance as well.

Part IV: Connecting the far ends: VWF cysteines in VWF life cycle

The sequential steps of VWF synthesis, packaging into WPBs, secretion, and removal from the circulation highlight the complexity of the VWF life cycle. It is not surprising therefore that mutations in the VWF molecule may affect 1 or more of these steps. In this last part of the review, we would like to illustrate how these steps are modulated in the context of VWD-related mutations, thereby focusing on cysteine mutations, given that cysteines play an important role in the proper folding and maturation of the protein.

Cysteine mutations and WPB formation

Cysteines contribute to the intrinsic folding of individual domains, tail-to-tail dimerization, and head-to-head multimerization. Mutations provoking the (dis)appearance of cysteines may affect each of these processes. But how do such mutations affect WPB formation? Intuitively, one would predict that impaired dimerization or multimerization would prevent the formation of WPBs. However, no general rule can be applied to such situations as exemplified by 3 Cys mutations located in the CK domain (p.Cys2739Tyr, p.Cys2754Trp, and p.Cys2773Ser). These mutations impair C-terminal dimerization and consequently only N-terminal dimerization occurs, preventing the formation of long multimers. Interestingly, each mutant has a different effect on WPB formation: no WPBs are formed with mutation p.Cys2739Tyr, whereas round organelles are produced with mutation p.Cys2754Trp.15 In contrast, normal rod-shaped WPBs are visible for mutant p.Cys2773Ser, demonstrating that WPBs may form even in the absence of multimerization.16 Interestingly, a broad analysis of several types of mutations further revealed that the opposite is also true, that is, the presence of VWF multimers is no guarantee for proper WPB formation.14 Based on the available information, 2 processes seem of critical importance for WPB formation: (1) correct arrangement of the propeptide/D′-D3 domains to form the core of the helical tubule, independent of whether they engage in disulfide bridging, and (2) assembly of the remainder of the domains (A1-CK) into the side-by-side bouquet structure. Distortion of this bouquet structure may compromise the alignment of the tubules that make up the interior of WPBs.

Cysteine mutations and secretion

Apart from WPB formation, cysteine mutations may also affect VWF secretion. Again, these effects seem mutation specific, with some mutants being secreted normally (eg, mutant p.Cys1225Gly), whereas others are retained within the cells (eg, p.Cys1149Arg), despite normal WPB formation. In a large study concerning VWD-type 1 patients, 5 of 15 mutations involving the (dis)appearance of a cysteine were associated with the absence of or partial response to desmopressin, further illustrating the heterogeneous effect of cysteine mutations on VWF secretion.17 How these mutants modulate secretion is unclear. They may be associated with an abnormal recruitment of components of the secretory machinery. Alternatively, misfolding of the proteins due to the cysteine mutations may alert quality control mechanisms that maneuver the mutated proteins to the intracellular degradation pathway.

Cysteine mutations and clearance

Despite intracellular quality control systems, small or large amounts of mutated proteins may escape the cell, including those with cysteine mutations. Are such mutants then cleared similarly to normal VWF? In the last several years, 35 different mutations have been associated with increased clearance of the protein.87 Interestingly, 14 of those (40%) involve a cysteine, indicating that cysteine mutations are overrepresented in this group of mutations. Three examples thereof have previously been described in detail by our group: p.Cys1130Phe, p.Cys1149Arg, and p.Cys2671Tyr.18 Patients with these mutations are characterized by increased VWF-propeptide/VWF-antigen ratios and a reduced survival of VWF antigen following desmopressin treatment. In addition, recombinant variants display reduced survival in a murine model.18 The mechanism by which these mutants are cleared more rapidly is currently unknown. Mutations may induce enhanced binding to the regular clearance receptors, such as LRP1. Indeed, we observed that mutant VWF/p.Cys1130Phe binds to LRP1 without the need for shear stress (Nikolett Wohner and P.J.L., unpublished observation). Alternatively, presence of mutations may provoke binding to clearance/scavenger receptors otherwise unable to recognize VWF. Studies in this direction are currently ongoing, and will provide more insight into how VWD-related mutations are associated with increased clearance of VWF.

Acknowledgments

Many interesting and relevant reports and reviews have been published concerning the topics discussed in this review. We apologize to those authors whose papers could not be referenced due to size restrictions.

This work was supported by grants from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-13-BSV1-0014; P.J.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: O.D.C., C.V.D., and P.J.L. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Peter J. Lenting, INSERM U770, 80 rue du General Leclerc, 94276 Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France; e-mail: peter.lenting@inserm.fr.

References

Author notes

P.J.L., O.D.C., and C.V.D. contributed equally to this review.