Key Points

Methylation profiling identifies subgroups of SMZL with distinct biological features.

Demethylating agents can reverse some of the adverse epigenetic alterations.

Abstract

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma is a rare lymphoma. Loss of 7q31 and somatic mutations affecting the NOTCH2 and KLF2 genes are the commonest genomic aberrations. Epigenetic changes can be pharmacologically reverted; therefore, identification of groups of patients with specific epigenomic alterations might have therapeutic relevance. Here we integrated genome-wide DNA-promoter methylation profiling with gene expression profiling, and clinical and biological variables. An unsupervised clustering analysis of a test series of 98 samples identified 2 clusters with different degrees of promoter methylation. The cluster comprising samples with higher-promoter methylation (High-M) had a poorer overall survival compared with the lower (Low-M) cluster. The prognostic relevance of the High-M phenotype was confirmed in an independent validation set of 36 patients. In the whole series, the High-M phenotype was associated with IGHV1-02 usage, mutations of NOTCH2 gene, 7q31-32 loss, and histologic transformation. In the High-M set, a number of tumor-suppressor genes were methylated and repressed. PRC2 subunit genes and several prosurvival lymphoma genes were unmethylated and overexpressed. A model based on the methylation of 3 genes (CACNB2, HTRA1, KLF4) identified a poorer-outcome patient subset. Exposure of splenic marginal zone lymphoma cell lines to a demethylating agent caused partial reversion of the High-M phenotype and inhibition of proliferation.

Introduction

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL) is a rare B-cell neoplasm recognized by the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) Lymphoma Classification as one of the 3 entities related to marginal-zone B cells.1 The disease involves the spleen, the bone marrow, and usually the peripheral blood, and it harbors distinctive genetic and clinical features. Loss of 7q31 and somatic mutations affecting the NOTCH2 gene are the commonest genomic aberrations, with a prevalence of 23% to 26%2,3 and 7% to 25%, respectively.4-7 Deregulation of DNA-promoter methylation has been implicated in B-cell lymphoma pathogenesis and can affect patient outcome.8-10 Aberrant DNA promoter methylation is strictly linked with alterations of the tumor cell epigenome and of the proteins involved in its regulation.11 Because epigenetic changes are susceptible to pharmacologic reversion, the identification of groups of patients with specific epigenomic alterations might have therapeutic relevance.12,13 The use of microarrays is a common and well-validated approach for DNA-methylation profiling to identify aberrantly methylated genes and to determine new clinically relevant disease stratification.8,14 Here we report the results of genome-wide promoter-methylation profiling of a large series of SMZL cases integrating gene expression and genetic and clinical data.

Material and methods

Tumor panel

Ninety-eight SMZL clinical specimens from 10 centers, as a test cohort, and 3 putative SMZL cell lines (Karpas1718, VL51, SSK41) were first studied. Thirty-six SMZL clinical specimens from 2 additional centers were analyzed as an independent validation cohort (Table 1). Kaplan-Meier log-rank test for overall survival (OS) was performed comparing test and validation cohorts, with no significant differences (P = .771; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). Diagnosis of SMZL was performed as previously reported,2 incorporating immunophenotype and clinical data based on the criteria proposed by WHO classification1 and by Matutes et al.15 SMZL samples with a fraction of neoplastic cells representing >70% of overall cellularity were selected for further studies. Three spleens from healthy individuals were included as nontumoral counterparts. High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was isolated.2 Informed consent was obtained from patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and following the procedures approved by the local ethical committees and institutional review boards of each participating institution. The study was approved by the Bellinzona Ethical Committee.

Clinical and biological features of test and validation SMZL series

| Variables . | Test cohort N (%) . | Validation cohort N (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Material analyzed obtained from spleen | 90/98 (92%) | 36/36 (100%) |

| Material analyzed obtained from peripheral blood | 8/98 (8%) | 0/36 (0%) |

| Age, y (median, range) | 68 (30-91) | 66 (52-77) |

| Sex (male) | 49/92 (53%) | 7/23 (30%) |

| B symptoms | 14/45 (31%) | 4/22 (18%) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 50/52 (96%) | 31/31 (100%) |

| Peripheral blood involvement | 29/44 (66%) | 21/23 (91%) |

| Stage (III, IV) | 58/59 (98%) | 23/23 (100%) |

| IILSS (high + intermediate) | 22/36 (61%) | 8/19 (42%) |

| NOTCH2 mutation status | 7/37 (19%) | 6/33 (18%) |

| Notch pathway mutation status | 12/37 (32%) | 6/33 (18%) |

| NF-κB pathway mutation status | 8/31 (26%) | 4/21 (19%) |

| DNA-remodeling genes mutation status | 2/3 (67%) | 0/2 (0%) |

| TP53 mutation status | 4/31 (13%) | 2/21 (10%) |

| 7q31-32 loss | 14/66 (21%) | 11/36 (31%) |

| 17p loss | 10/66 (15%) | 6/36 (17%) |

| High-M phenotype | 21/98 (21%) | 12/36 (33%) |

| KM3 phenotype | 28/98 (29%) | 12/36 (33%) |

| IGHV1-02 usage | 12/65 (18%) | 4/22 (18%) |

| LDH increased | 15/40 (38%) | 4/22 (18%) |

| HCV status | 6/48 (13%) | 7/36 (19%) |

| Histologic transformation to high-grade lymphoma | 2/43 (5%) | 3/17 (18%) |

| Dead | 28/91 (31%) | 6/36 (17%) |

| Overall survival, mo (median, range) | 69.20 (3-223) | 58.10 (2-194) |

| Splenectomy | 34/50 (68%) | 3/24 (13%) |

| Treatment with CHT | 22/49 (45%) | 17/24 (44%) |

| GEP available | 10/98 (10%) | 0/36 (0%) |

| Variables . | Test cohort N (%) . | Validation cohort N (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Material analyzed obtained from spleen | 90/98 (92%) | 36/36 (100%) |

| Material analyzed obtained from peripheral blood | 8/98 (8%) | 0/36 (0%) |

| Age, y (median, range) | 68 (30-91) | 66 (52-77) |

| Sex (male) | 49/92 (53%) | 7/23 (30%) |

| B symptoms | 14/45 (31%) | 4/22 (18%) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 50/52 (96%) | 31/31 (100%) |

| Peripheral blood involvement | 29/44 (66%) | 21/23 (91%) |

| Stage (III, IV) | 58/59 (98%) | 23/23 (100%) |

| IILSS (high + intermediate) | 22/36 (61%) | 8/19 (42%) |

| NOTCH2 mutation status | 7/37 (19%) | 6/33 (18%) |

| Notch pathway mutation status | 12/37 (32%) | 6/33 (18%) |

| NF-κB pathway mutation status | 8/31 (26%) | 4/21 (19%) |

| DNA-remodeling genes mutation status | 2/3 (67%) | 0/2 (0%) |

| TP53 mutation status | 4/31 (13%) | 2/21 (10%) |

| 7q31-32 loss | 14/66 (21%) | 11/36 (31%) |

| 17p loss | 10/66 (15%) | 6/36 (17%) |

| High-M phenotype | 21/98 (21%) | 12/36 (33%) |

| KM3 phenotype | 28/98 (29%) | 12/36 (33%) |

| IGHV1-02 usage | 12/65 (18%) | 4/22 (18%) |

| LDH increased | 15/40 (38%) | 4/22 (18%) |

| HCV status | 6/48 (13%) | 7/36 (19%) |

| Histologic transformation to high-grade lymphoma | 2/43 (5%) | 3/17 (18%) |

| Dead | 28/91 (31%) | 6/36 (17%) |

| Overall survival, mo (median, range) | 69.20 (3-223) | 58.10 (2-194) |

| Splenectomy | 34/50 (68%) | 3/24 (13%) |

| Treatment with CHT | 22/49 (45%) | 17/24 (44%) |

| GEP available | 10/98 (10%) | 0/36 (0%) |

CHT, chemotherapy; GEP, gene expression profiling; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IILSS, Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi Score for SMZL, including hemoglobin, LDH and albumin levels; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

The majority of patient samples were splenic biopsies (94%, 126/134) and 8 of 134 cases represented peripheral blood specimens (6%).

Genome-wide promoter-methylation profiling

Genome-wide promoter-methylation profiling was performed with the Infinium HumanMethylation27 arrays (Illumina, San Diego, CA), and signal intensities and β values were exported and processed as previously described.16

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction for methylation

The methylation profiling data were validated via quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) for methylation using the EpiTect Methyl II PCR Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Gene-expression profiling, genome-wide DNA profiling, and IGHV mutational status

Gene-expression profiling (GEP) data, from Affymetrix HU133 Plus 2.0 arrays, was extracted from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset GSE35082. Copy number alterations (CNA) data were obtained from our previous publications on genome-wide DNA profiling.2,4,17 Mutation status and family-usage of immunoglobulin variable heavy-chain (IGHV) genes were derived from previous studies.2,18

Somatic mutations analysis

Decitabine treatment of SMZL primary cells and cell lines

The SMZL cell lines Karpas1718, VL51, and SSK41 were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Primary SMZL cells were isolated by centrifugation over a Ficoll-Hypaque layer and cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum for 3 days. Primary SMZL cells were stimulated with DSP-30 (CpG oligonucleotide) and IL2 on the second day of culture using the PREMIX AmpliB kit (AmpliTech SARL, Compaigne, France), following the manufacturer’ protocol. The antiproliferative activity of decitabine was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay on cell lines exposed to dimethyl sulfoxide or to increasing doses of decitabine (Sigma-Aldrich, Fluka Chemie GmbH, Buchs, Switzerland) for 72 hours, as previously described.19 Total RNA and genomic DNA were isolated from cells after 48 hours (primary cells) or 72 hours (cell lines) of exposure to dimethyl sulfoxide or decitabine (7.5 µM), as previously reported.16,20 GEP was performed with the Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip, and methylation profiling with the Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip, both according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Data analysis

Signal intensities and β values were exported using Illumina Beadstudio 2.0 software at default settings. For quality control, histograms and boxplots were plotted for signal intensities and β values; similarly, probe-wise normalized standard errors of signal intensities were also computed and plotted. Quality control was performed by visual inspection of these histograms and boxplots and also of principal component analysis plots.

Probes mapping outside CpG islands as defined by the manufacturers21 were discarded, whereas all of the probes mapping to CpG sites (20 006 probes, corresponding to 9200 genes) were used for further analysis. Unsupervised analyses on the Infinium HumanMethylation27 β values using principal component analysis were performed using the Expander22 and Genomics Suite 6.4 (Partek Inc., St. Louis, MO) tools. To identify the differentially methylated probes, both moderated Student t test (limma) and Fisher’s exact test were performed on the whole CpG-probe set β values, treating the latter as continuous or categorical data, respectively.16 For the Fisher’s exact test, the probes were classified as “methylated” (β value ≥0.3) or “unmethylated” (β value <0.3).16 Differentially-expressed genes were calculated with the limma test on GEP data. The false discovery rate (FDR, Benjamini-Hochberg correction) was calculated to control for false positives: probes with FDR < .05 were considered significant. The probes were ranked according to decreasing absolute β-value change for methylation profiling and according to decreasing fold change for GEP. Absolute β-value change and fold-change parameters were calculated by comparing the average β values or expression values. Functional analysis was performed on the collapsed gene symbol list using DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery)23 and GSEA (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis)24 with the MSigDB (Molecular Signatures Database)25 C2-C7 gene sets. Gene sets with FDR <0.25 and normalized enrichment score >1.25 or <−1.25 were considered significantly enriched. Integrated networks were built using CytoScape software26 as previously reported.27

Either the χ2 test or the Fisher’s exact test was used for testing associations in 2-way tables, as appropriate, and P ≤ .05 (2-sided test) was considered statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to determinate the OS, and differences between the groups were tested with the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression was used to study the association between biological and clinical features, and OS. Analyses were performed using the R environment (R Studio console; RStudio, Boston, MA). A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling identifies a group of SMZL patients with inferior outcome

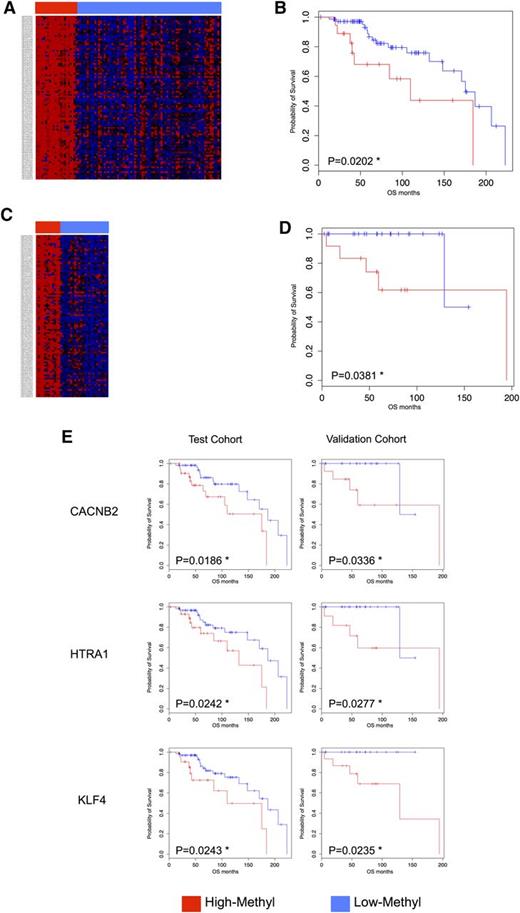

The genome-wide DNA-promoter methylation status of 9200 genes was analyzed in 101 SMZL samples, comprising 98 clinical specimens and 3 cell lines. Unsupervised clustering analysis using the 100 top-ranked probes by standard deviation (TOP-100) identified 2 main clusters (Figure 1A). One cluster comprised 21 cases (21/98, 21%) and was characterized by a generalized high degree of promoter DNA methylation (High-M cluster). This cluster had a significantly poorer OS than the remaining 77 of 98 (79%) cases (Low-M cluster) (P = .0202) (Figure 1B).

DNA methylation profiling identifies subgroups of SMZL patients with different clinical outcome. (A) Heat map for test series using 100 top-ranked probes by standard deviation (TOP-100). Unsupervised clustering analysis (Euclidean distance, complete linkage method) using the TOP-100 probes identified 2 main clusters: High-M (red) had a significantly poorer overall survival (OS) (B) than the Low-M cases (blue). (C) Heat map in an independent validation cohort of 36 SMZL patients using TOP-100; an unsupervised clustering (Euclidean distance, complete linkage method) identified again 2 clusters: 1 cluster showed High-M phenotype (red) and an inferior OS (D). (E) Kaplan-Meier log-rank curves for CACNB2 (cg01805540), HTRA1 (cg25920792), and KLF4 (cg07309102) genes in both the test and the validation cohorts. The 3 genes were significantly associated with OS in both cohorts. Red, High-M phenotype; blue, Low-M phenotype; *P < .05.

DNA methylation profiling identifies subgroups of SMZL patients with different clinical outcome. (A) Heat map for test series using 100 top-ranked probes by standard deviation (TOP-100). Unsupervised clustering analysis (Euclidean distance, complete linkage method) using the TOP-100 probes identified 2 main clusters: High-M (red) had a significantly poorer overall survival (OS) (B) than the Low-M cases (blue). (C) Heat map in an independent validation cohort of 36 SMZL patients using TOP-100; an unsupervised clustering (Euclidean distance, complete linkage method) identified again 2 clusters: 1 cluster showed High-M phenotype (red) and an inferior OS (D). (E) Kaplan-Meier log-rank curves for CACNB2 (cg01805540), HTRA1 (cg25920792), and KLF4 (cg07309102) genes in both the test and the validation cohorts. The 3 genes were significantly associated with OS in both cohorts. Red, High-M phenotype; blue, Low-M phenotype; *P < .05.

The prognostic relevance of the High-M phenotype was confirmed in an independent validation cohort, in which unsupervised clustering using the TOP-100 probes again identified 2 clusters with one (12/36, 33%) bearing a methylation profile similar to the High-M (Figure 1C) and an inferior OS (P = .0381) (Figure 1D).

To identify the genes whose promoter methylation status had the highest correlation with OS, a Kaplan-Meier log-rank test was carried out for the TOP-100 probes in both the test and the validation cohorts. Three probes (cg07309102, cg01805540, cg25920792) corresponding to the promoter regions of the KLF4, CACNB2, and HTRA1 genes were significantly associated with OS in both cohorts. Methylation status for these 3 and for an additional 3 genes (ARRDC4, cg09149294; CCDC23, cg19101893; ALS2CL, cg05369142) was validated using the MethylScreen technology that combines DNA digestion with both methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes and methylation-dependent restriction enzymes.28 Microarray-derived methylation status confirmed in 8 of 8 cases for KLF4 and ARRDC4 and in 7/8 for CACNB2, HTRA1, CCDC23, and ALS2CL (supplemental Figure 2).

Genome-wide promoter DNA methylation status is associated with different clinical and biological features and is an independent prognostic factor for OS

We pooled the test and the validation series for further analyses. High-M was significantly associated with an inferior OS (P = .0032; HR 2.54; 95% CI, 1.23-5.49) (Table 2 and supplemental Figure 3). The High-M group (33/134, 25%) showed enrichment in IGHV1-02 usage, mutations of the NOTCH2 gene or of members of the Notch pathway, 7q31-32 loss and histologic transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (Table 3). We then assessed the impact of the methylation status of KLF4, CACNB2 and HTRA1 genes (KM3), which were significant in both the test and the validation series. KM3 was able to discriminate classes of patients with highly significant differences in OS (P = .0019; HR 2.64; 95% CI, 1.29-5.43) (Table 2 and supplemental Figure 3).

Prognostic significance of High-M and KM3 conditions

| Variables . | Kaplan-Meier log-rank test . | Univariate Cox model . | Multivariate Cox model (High-M, age 60 y, IILSS, 7q31.32 loss, 17p loss) . | Multivariate Cox model (KM3, age 60 y, IILSS, 7q31.32 loss, 17p loss) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-grade transformation* | .0545d | .0640d | ||

| Increased LDH | .0426a | .0323a | ||

| 7q31.32 loss | .0436a | .0510d | .1303 | .1843 |

| 17p loss | .0713d | .0259a | .1731 | .1314 |

| Age <60 y | .0330a | .0450a | .0984 | .1256 |

| IILSS† | .0133b | .0398a | .0122a | .0148a |

| High-M phenotype | .0032b | .0048b | .0143a | |

| KM3 phenotype | .0019b | .0082a | .0186a | |

| KLF4 (cg07309102) | .0031b | .0046b | ||

| CACNB2 (cg01805540) | .0022b | .0034b | ||

| HTRA1 (cg25920792) | .0030b | .0045b | ||

| Likelihood ratio test | .0001c | .0002c | ||

| Wald test | .0457a | .0462a | ||

| Log-rank test | .0005b | .0007b |

| Variables . | Kaplan-Meier log-rank test . | Univariate Cox model . | Multivariate Cox model (High-M, age 60 y, IILSS, 7q31.32 loss, 17p loss) . | Multivariate Cox model (KM3, age 60 y, IILSS, 7q31.32 loss, 17p loss) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-grade transformation* | .0545d | .0640d | ||

| Increased LDH | .0426a | .0323a | ||

| 7q31.32 loss | .0436a | .0510d | .1303 | .1843 |

| 17p loss | .0713d | .0259a | .1731 | .1314 |

| Age <60 y | .0330a | .0450a | .0984 | .1256 |

| IILSS† | .0133b | .0398a | .0122a | .0148a |

| High-M phenotype | .0032b | .0048b | .0143a | |

| KM3 phenotype | .0019b | .0082a | .0186a | |

| KLF4 (cg07309102) | .0031b | .0046b | ||

| CACNB2 (cg01805540) | .0022b | .0034b | ||

| HTRA1 (cg25920792) | .0030b | .0045b | ||

| Likelihood ratio test | .0001c | .0002c | ||

| Wald test | .0457a | .0462a | ||

| Log-rank test | .0005b | .0007b |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Kaplan-Meier log-rank test and univariate Cox regression were performed for every variable. Multivariate Cox regression models were adjusted for either High-M and KM3 conditions or the significant variables in the univariate regression.

Few cases, statistical error for multivariate model.

IILSS including hemoglobin, LDH, and albumin levels: a, P < .05, b, P < .005, c, P < .0005; d, borderline significance.

Association between clinical and biological variables and High-M phenotype in SMZL patients

| Variables . | High-M phenotype . | Low-M phenotype . | Fisher’s exact test . | Pearson χ2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notch pathway mutation | 10/21 (48%) | 7/46 (15%) | .0072a | .0047b |

| NOTCH2 mutation | 8/21 (38%) | 4/46 (9%) | .0063a | .0036b |

| IGHV1-02 usage | 8/22 (36%) | 8/65 (12%) | .0225a | .0118a |

| HCV status | 2/26 (8%) | 11/58 (19%) | .3273d | .1866d |

| High grade transformation | 5/13 (38%) | 0/47 (0%) | .0002c | <.0001c |

| Increased LDH | 8/18 (44%) | 11/44 (25%) | .1445d | .1317d |

| 7q31.32 loss | 12/28 (43%) | 13/74 (18%) | .0184a | .0081a |

| 17p loss | 5/28 (18%) | 11/74 (15%) | .7631d | .7108d |

| age <60 y | 16/22 (73%) | 60/85 (71%) | 1.0000d | .8437d |

| IILSS* | 11/16 (69%) | 19/39 (49%) | .2374d | .1754d |

| KM3 phenotype | 33/33 (100%) | 5/102 (5%) | <.0001c | <.0001c |

| KLF4 (cg07309102) | 31/33 (94%) | 9/101 (9%) | <.0001c | <.0001c |

| CACNB2 (cg01805540) | 30/33 (91%) | 18/101 (18%) | <.0001c | <.0001c |

| HTRA1 (cg25920792) | 31/33 (94%) | 11/101 (11%) | <.0001c | <.0001c |

| Variables . | High-M phenotype . | Low-M phenotype . | Fisher’s exact test . | Pearson χ2 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notch pathway mutation | 10/21 (48%) | 7/46 (15%) | .0072a | .0047b |

| NOTCH2 mutation | 8/21 (38%) | 4/46 (9%) | .0063a | .0036b |

| IGHV1-02 usage | 8/22 (36%) | 8/65 (12%) | .0225a | .0118a |

| HCV status | 2/26 (8%) | 11/58 (19%) | .3273d | .1866d |

| High grade transformation | 5/13 (38%) | 0/47 (0%) | .0002c | <.0001c |

| Increased LDH | 8/18 (44%) | 11/44 (25%) | .1445d | .1317d |

| 7q31.32 loss | 12/28 (43%) | 13/74 (18%) | .0184a | .0081a |

| 17p loss | 5/28 (18%) | 11/74 (15%) | .7631d | .7108d |

| age <60 y | 16/22 (73%) | 60/85 (71%) | 1.0000d | .8437d |

| IILSS* | 11/16 (69%) | 19/39 (49%) | .2374d | .1754d |

| KM3 phenotype | 33/33 (100%) | 5/102 (5%) | <.0001c | <.0001c |

| KLF4 (cg07309102) | 31/33 (94%) | 9/101 (9%) | <.0001c | <.0001c |

| CACNB2 (cg01805540) | 30/33 (91%) | 18/101 (18%) | <.0001c | <.0001c |

| HTRA1 (cg25920792) | 31/33 (94%) | 11/101 (11%) | <.0001c | <.0001c |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

For IILSS, the comparison was high and intermediate value vs low value: a, P < .05; b, P < .005; c, P < .0005; d, borderline significance.

The High-M status and the KM3 status were separately evaluated for their independent prognostic significance in Cox regression models adjusted for age, Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi Score for SMZL (IILSS),29 7q31-32 loss, and 17p loss. Both High-M and KM3 conditions maintained their prognostic significance for OS (High-M, P = .0143; KM3, P = .0186) (Table 2). We then performed a log-rank test on the IILSS low-scored cohort of SMZL patients to investigate whether methylation status might identify a poorer-outcome subgroup among the low-risk patients as well. Both High-M and KM3 discriminated a set of patients harboring significantly shorter OS (supplemental Figure 4).

Methylation targets genes involved in important biological processes

To investigate the biological meaning of the observed differences in methylation status among SMZL samples in the spleen, supervised analysis between High-M and Low-M cases identified 3410 differentially methylated probes (corresponding to 1943 methylated and 512 unmethylated genes). The probes more methylated in the High-M cluster were significantly enriched for promoter regions of PRC2-complex targets (including EZH2 and SUZ12 targets); genes harboring tri-methylation marks H3K27me3 and H3K4me3; genes involved in chromatin remodeling (HDAC targets); DNA-binding genes (including HOX, SOX, and GATA family members); genes related to stem cells and cell differentiation, WNT signature, G-protein– and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1–signaling pathways; and genes downregulated by CDH1, TP53, and TP63 tumor suppressors. Several tumor suppressor genes were also highly methylated in the High-M such as KLF4, DAPK1, CDKN1C, CDKN2A/B/D, CDH1, CDH2, WT1, RARB, GATA4, and TIMP3. Conversely, unmethylated probes in the High-M cluster were mapped to the promoter regions of different prosurvival genes (such as TCL1B, IL2RB, BCL10, CD79B, CARD11, BCL2A1, APRIL, IFNG, FGF1, and PIK3CB), PRC2-complex genes (EZH2, EED, and SUZ12), and genes involved in proliferation and cell cycle (IL2, PI3K/AKT, NF-κB and B-cell receptor signaling pathways), and genes upregulated by MYC, E2F, and IRF4 (Figure 2).

Integration of methylation profiling and gene expression. Hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distance, complete linkage method) of genes with FDR <0.05 in either limma Student t test comparing High-M vs Low-M for GE (A) and methylation (B) profiling. Red and blue represent higher and lower methylation (heat map on the right), respectively, and red and green represent high- and low-level expression (heat map on the left), respectively.

Integration of methylation profiling and gene expression. Hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distance, complete linkage method) of genes with FDR <0.05 in either limma Student t test comparing High-M vs Low-M for GE (A) and methylation (B) profiling. Red and blue represent higher and lower methylation (heat map on the right), respectively, and red and green represent high- and low-level expression (heat map on the left), respectively.

We integrated the methylation data with the paired GEP data. In general, there was an inverse correlation between methylation status and expression levels (R = –0.3593, β-slope = –3.2693, P < .0001). Then we built a functional network, which showed that the observed methylation changes had a direct effect on transcript levels (Figure 3). The highly-methylated and downregulated genes in the High-M group had diverse functions, including epigenetic modifications (H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 methylation marks, PRC2-complex targets, and chromatin remodeling) and roles in cell fate and differentiation (F, Notch, Hedgehog, TGF-β, stem cells), cell-cell communication and signal transduction (G-protein signaling, cell-cell interactions), and negatively-regulated targets of proapoptotic genes (CDH1, TP53, and TP63). Conversely, the genes with low methylation and upregulated in High-M cases affected cell cycle and DNA repair, prosurvival processes (B-cell receptor and NF-κB signaling pathways, lymphocyte activation, and positively regulated targets of MYC and IRF4), the complement cascade, and the immune system (Il2, TLR, and IFN signaling pathways).

Integrated networks based on methylation and expression data obtained in SMZL samples. Integrated network for genome-wide DNA methylation profiling (A) and GEP (B) comparing High-M and Low-M clusters of SMZL patients. (C) Markov cluster algorithm (MCL) clustering identified 4 clusters that were annotated using the wordcloud plugin on Cytoscape (D). Magenta and yellow represent high- and low-level methylation (A), respectively, and red and green represent high- and low-level gene expression (B), respectively.

Integrated networks based on methylation and expression data obtained in SMZL samples. Integrated network for genome-wide DNA methylation profiling (A) and GEP (B) comparing High-M and Low-M clusters of SMZL patients. (C) Markov cluster algorithm (MCL) clustering identified 4 clusters that were annotated using the wordcloud plugin on Cytoscape (D). Magenta and yellow represent high- and low-level methylation (A), respectively, and red and green represent high- and low-level gene expression (B), respectively.

The EZH2, EED, and SUZ12 genes, coding for subunits of the PRC2 complex, appeared unmethylated in their promoter regions and overexpressed in the High-M cases, whereas EZH2 target genes and genes harboring the H3K27me3 mark had methylated promoters and downregulated expression. A number of known tumor-suppressor genes were highly methylated and downregulated in High-M cases, including KLF4, DAPK1, CDKN2D, CDKN1C, CDH1, CDH2, SPRY2, CBX7, WT1, and TIMP3. Known prosurvival lymphoma genes, such as TCL1A/B, CARD11, IL2RB, BCL2L10, IFNG, UBD, and PIK3CB, showed low methylation and increased expression in High-M cases (Figures 2 and 3).

Genome-wide promoter-DNA methylation status of SMZL differs from its normal counterpart

The methylation profiles of High-M and Low-M SMZL samples derived from spleen were first separately compared with spleens from healthy donors (Non-Tum) using GSEA. The conditions differed for 833 gene sets, of which 272 (33%) were methylated in both High-M and Low-M compared with Non-Tum; 512 gene sets (61%) were methylated only in the High-M; and 49 (6%) in Low-M compared with Non-Tum. Methylated genes shared by both High-M and Low-M were related to H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 marks, genes methylated in cancer, G-protein signaling, and cell-cell interactions. The genes only methylated in High-M were enriched in PRC2-complex targets (EZH2 and SUZ12), genes implicated in stem-cell signatures, HDAC targets linked to senescence, targets of tumor-suppressor genes (CDH1, TP53, and TP63) and transcripts involved in cell proliferation, Hedgehog (Hh), TGFB- and FGFR-signaling pathways, and Notch targets upregulated after exposure to the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. Conversely, the genes methylated solely in the Low-M cluster were mainly associated with positive regulation of phosphorylation, cell adhesion, and components of extracellular matrix space (Figure 3).

Finally, the promoter regions significantly less methylated in SMZL (both High-M and Low-M clusters) than in the Non-Tum were enriched in genes with cell-cycle and DNA repair functions, MYC targets, and IL2 and AKT signaling pathways. Specifically in the High-M but not the Low-M cluster, low-methylated genes were also involved in B-cell activation, the NF-kB signaling pathway, and immune functions (Figure 3).

The 8 SMZL samples derived from peripheral blood were compared with 6 CD19+ B-cell samples isolated from healthy donors, and they showed deregulation by methylation of the same biological processes identified in the comparison based on specimens derived from spleen (data not shown).

Pharmacologic treatment can reverse the methylation phenotype

To better understand the role of the high degree of promoter DNA methylation observed in SMZL, we assessed whether pharmacologic treatment could revert the methylation pattern. The 3 SMZL cell lines, which coclustered with the High-M splenic MZL samples, were exposed to the demethylating agent decitabine for 72 hours. All 3 cell lines were sensitive to the drug and showed a reduction in cell proliferation with IC50 values <2 µM (1.80 µM for Karpas1718, 0.51 µM for SSK41, and 1.77 µM for VL51). A decrease in promoter methylation was observed in 2593 probes and was associated with upregulated gene expression in 664 (26%). Again, we generated a network integrating both gene expression and promoter methylation changes after decitabine treatment (Figure 4). Hypomethylated genes and re-expressed transcripts included those involved in epigenetic reprogramming (response to epigenetic inhibitor drugs; genes silenced by methylation; targets of epigenetic writers EZH2, BMI1, and DNMT1), proapoptotic processes (upregulated targets of the tumor suppressors RB1 and TP53), negatively-regulated targets of prosurvival proteins (MYC, BCL2, STAT3/5, and CD40), cell differentiation (Hedgehog, WNT signatures, and gene targets upregulated after Notch inhibition), immune function (inflammatory response), and cell communication (ion homeostasis, cell-cell interactions) (Figure 4). The re-expressed transcripts also contained several tumor-suppressor genes (eg, KLF4, SOCS1, NFKBIA, CDKN1A, CDKN2D, KAT2B, CYLD, DAPK1, FBXW4).

Integrated networks based on methylation and expression data obtained in SMZL cell lines treated with decitabine. Network integrating both genome-wide DNA methylation profiling (A) and GEP (B) changes after decitabine treatment for 72 hours in the 3 SMZL cell lines (Karpas1718, VL51, and SSK41). (C) Markov cluster algorithm (MCL) clustering identified 5 clusters that were annotated using the wordcloud plugin on Cytoscape (D). Genes highlighted in green were high-methylated and repressed, whereas those in red were low-methylated and upregulated in High-M. Red and blue represent high- and low-level methylation (A), respectively, and red and green represent high- and low-level gene expression (B), respectively.

Integrated networks based on methylation and expression data obtained in SMZL cell lines treated with decitabine. Network integrating both genome-wide DNA methylation profiling (A) and GEP (B) changes after decitabine treatment for 72 hours in the 3 SMZL cell lines (Karpas1718, VL51, and SSK41). (C) Markov cluster algorithm (MCL) clustering identified 5 clusters that were annotated using the wordcloud plugin on Cytoscape (D). Genes highlighted in green were high-methylated and repressed, whereas those in red were low-methylated and upregulated in High-M. Red and blue represent high- and low-level methylation (A), respectively, and red and green represent high- and low-level gene expression (B), respectively.

We also found that 31% (593/1943) of highly-methylated genes in the High-M signature were demethylated after treatment, and 33% (195/593) of them were also re-expressed. Among the 3 genes most correlated with outcome, CACNB2 was demethylated and re-expressed. HTRA1 was demethylated but not significantly re-expressed. KLF4 was re-expressed without significant changes in its promoter methylation status for the cg07309102 probe (although it was demethylated at the cg13894301 probe). The increased CACNB2 expression after decitabine treatment was confirmed by qRT-PCR for the 3 cell lines (supplemental Figure 5).

The finding that the methylation changes affecting gene-expression levels involved the same biological processes in both the microarray analysis of SMZL specimens and in the cell-line experiments underlined the relevant role of these biological processes.

Finally, we determined whether decitabine could revert the methylation profile also on SMZL primary specimens. Cells from both High-M (n = 2) and Low-M cases (n = 2) were exposed to the drug for 48 hours. For all patients, a decrease in DNA-promoter methylation was observed for at least 2 of 3 promoters regions analyzed (supplemental Figure 6).

Discussion

We analyzed a large series of SMZL cases by genome-wide promoter-methylation arrays to define prognostically relevant subgroups and to better understand SMZL biology. Our results indicate that: (1) a high degree of genome-wide DNA-promoter methylation identifies a group of SMZL patients with an inferior outcome, a higher risk of histologic transformation, and higher prevalence of NOTCH2 mutations and 7q31-32 loss; (2) promoter methylation affects important biological pathways; and (3) pharmacologic treatment with a demethylating agent appeared to at least partially reverse the methylation-related phenotype.

The current work represents the largest study of genome-wide DNA promoter methylation profiling in SMZL and represents a further step in the understanding of this lymphoma subtype after having reported its gene expression and miRNA profiles30 and its genome-wide DNA profiling,2 and having characterized the most recurrent somatic mutations in this entity.4,7,31,32 Disruption of DNA-promoter methylation is an important pathogenetic mechanism in lymphomas and can affect clinical outcome.8-10 Here, a test and validation approach followed by multivariate analyses identified a cluster of SMZL characterized by a high degree of promoter methylation and patient outcomes significantly inferior to cases belonging to the cluster with lower levels of methylation. Furthermore, a model based on the methylation status of only 3 genes (CACNB2, HTRA1, and KLF4) was able to identify a group of SMZL with significantly different outcomes and appears worthy of further external validation in an independent series of cases.

The cases with high promoter methylation were characterized by peculiar biological features, which might contribute to the observed negative prognostic significance: 7q31-32 deletion, NOTCH2 mutation, IGHV1-02 usage, and histologic transformation. The association of the high methylator phenotype with the presence of mutations in Notch pathway genes is a new observation. Mutations of NOTCH2 or other related transcripts are believed to a have a direct role in SMZL pathogenesis4,5,33 and have been previously associated with 7q31-q32 loss.4 Our results suggest that DNA hypermethylation could act concomitantly with 7q31-32 deletion, NOTCH2 mutation, and IGHV1-02, defining a distinct genetic and epigenetic subgroup of SMZL.

The High-M cluster was characterized by strong epigenetic disruption showing deregulation in the methylation and gene-expression profiles of genes involved in crucial processes for epigenetic regulation. Genes involved in chromatin remodeling and DNA-binding genes including a number of HOX, SOX, and GATA family genes were highly methylated and repressed. Conversely, within the High-M cluster, we found low-methylated and upregulated genes related to cell cycle, DNA repair, and, interestingly, genes coding for PRC2 histone methyltransferase–complex subunits, including EED, SUZ12, and EZH2. The latter, the PRC2-complex catalytic subunit, is the target of recurrent somatic mutations in lymphomas including SMZL,6,34 and its pharmacologic inhibition represents one of the new actively explored therapeutic modalities.35-37 Transcriptional silencing driven by CpG methylation is strictly connected with the activity of the PRC2-complex, which represses expression of differentiation genes through tri-methylation of lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3).11 Importantly, when compared with nontumoral splenic tissue, both Low-M and High-M SMZL cases presented high methylation and downregulation of genes harboring H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 methylation marks, and the phenomenon was more significant for the High-M cases. In the same manner, genes involved in B-cell activation and NF-κB signaling were unmethylated and highly expressed in High-M, suggesting a prevalence of activation in prosurvival processes for this subset.

A number of tumor suppressor genes appeared to be hypermethylated and downregulated in the High-M cluster, including KLF4, DAPK1, CDKN1C, CDKN2D, and CDH1/2. Epigenetic silencing of the transcription factor KLF4 causes loss of cell-cycle control and protects neoplastic B cells from apoptosis,38 and its low expression correlates with poor outcome in Burkitt lymphoma.39 One mechanism by which KLF4 contributes to cell-cycle arrest is the transcriptional activation of several cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, and in the High-M cluster, some of these, such as CDKN1A (p21), CDKN1B (p27), and CDKN1C (p57), appeared downregulated, and p57, also appeared hypermethylated. In addition, several negatively-regulated downstream targets of KLF4 were upregulated in the High-M cluster, including CXCL10, BCL2, BIRC5, and MSC/ABF-1, whereas TNFRSF10C and CDH1, which are positively regulated by KLF4,38,40 appeared downregulated. Together with the observation that KLF4-promoter methylation was highly associated with an inferior outcome in SMZL patients, these data suggest a putative important role of KLF4 inactivation and of the loss of cell-cycle control in High-M cases, which also affects patient outcome.

Cell-cycle deregulation in SMZL was also underlined by the hypermethylation and downregulation of the CDKN2D gene (coding for p19), and by the enrichment of several gene sets involved in the cell cycle or of negatively regulated targets for the TP53 and TP63 genes. CDKN2D is a tumor-suppressor gene in B-cell malignancies41 and specifically inhibits CDK4 and CDK6,42 which were upregulated in High-M SMZL. Members of the RUNX and GADD45 gene families (RUNX1/3, GADD45B/G), which cooperate with p53 in the p53-dependent response to DNA damage,43,44 were also downregulated in the High-M cluster and, furthermore, GADD45G was highly methylated. Thus, methylation-mediated silencing of cell cycle– and DNA damage–related genes appeared to be frequent events in High-M SMZL.

A number of oncogenes and genes with a prosurvival effect were unmethylated and overexpressed in High-M cases, such as TCL1A/B, BIRC5, CD79B, PIK3CB, and genes related to prosurvival signatures in cancer, upregulated targets of oncogenes (MYC and IRF4), and members of the NF-κB, AKT/PI3K, B-cell receptor, and IL2 signaling pathways. This indicates that the deregulation of promoter methylation seen in High-M SMZL cases was paired with gene expression changes that would provide a survival advantage to the lymphoma cells, contributing to the inferior outcome of this group of SMZL patients.

Finally, we explored the ability of decitabine to affect the observed methylation changes. Decitabine is a demethylating agent clinically approved for the treatment of older acute myeloid leukemia patients not eligible for standard therapies or for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome.45 The exposure of 3 High-M SMZL cell lines to the drug led to the re-expression and hypomethylation of many genes, including targets of methyltransferases (EZH2 and DNMT1) and genes previously reported as silenced by methylation. Decitabine also led to the expression of tumor-suppressor genes (KLF4, SOCS1, NFKBIA, CDKN1A, CDKN2D, KAT2B, CYLD, DAPK1 and FBXW4) and targets of RB1 and TP53, upregulation of negatively regulated targets of MYC, BCL2, STAT3/5, and CD40 prosurvival genes, and genes contributing to stem-cells signatures (Hh, Wnt, Notch-inhibition targets). Thus, there is strong evidence that treatment with demethylating agents might be useful for High-M SMZL patients to at least partially reverse the High-M phenotype. Furthermore, changes in methylation correlated with decreased cell proliferation of the 3 SMZL cell lines. Demethylating agents might be combined with additional epigenetic drugs, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors or BET bromodomain inhibitors that have shown activity in preclinical SMZL models,46-48 and with drugs such as ibrutinib,49 idelalisib,50 or bortezomib,51 targeting the pathways that appeared activated in High-M cases.

In conclusion, studying the genome-wide DNA-promoter methylation status of a large series of SMZL samples allowed the identification of a subgroup of SMZL with a high degree of DNA-promoter methylation associated with inferior outcome and peculiar biological features. The interrogation of only 3 genes (KLF4, CACNB2, and HTRA1) appeared able to identify higher-risk cases, and a similar approach appears to be worthy of validation in independent series. Aberrant DNA methylation seems to play a relevant role in determining the pathogenesis and the progression of SMZL, affecting important biological pathways. Treatment of cell lines with a demethylating agent led to a partial reversion of the phenotype, providing the rational for combination regimens including epigenetic drugs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Fondazione Ticinese per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Jubiläumsstiftung Swiss Life, the Nelia et Amadeo Barletta Foundation, and Oncosuisse (grant OCS-02034-02- 2007) (F.B.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.J.A. performed statistical analysis and validation experiments, interpreted data, and co-wrote the manuscript; A.R. performed profiling and validation experiments; A.A.M. performed in vitro experiments; I.K. and L.C. performed statistical analysis; E.F.R., J.A.M.-C., D.O., L.A., L.B., R.M., C.T., J.B., F.F., A.Z., M.B., M.M., F.F., S.D., M.P., G.B., and M.A.P. collected and characterized tumor samples; G.G., D.R., and E.Z. collected and characterized tumor samples and codesigned research; F.B. codesigned research, interpreted data, and cowrote the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.B. received research funds from Oncoethix SA, Sigma-Tau, and Italfarmaco. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Francesco Bertoni, Lymphoma and Genomics Research Program, IOR Institute of Oncology Research, IOSI Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, via Vincenzo Vela 6, 6500 Bellinzona, Switzerland; e-mail: frbertoni@mac.com.

References

Author notes

A.J.A. and A.R. contributed equally to this study.