Key Points

In human aggressive B-NHLs, HSPH1 favors c-Myc and Bcl-6 expression, and its inhibition provides significant antilymphoma activity.

HSPH1 is expressed in function of Bcl-6 and c-Myc and constitutes a valuable alternative lymphoma therapeutic target of aggressive B-NHLs.

Abstract

We have shown that human B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (B-NHLs) express heat shock protein (HSP)H1/105 in function of their aggressiveness. Here, we now clarify its role as a functional B-NHL target by testing the hypothesis that it promotes the stabilization of key lymphoma oncoproteins. HSPH1 silencing in 4 models of aggressive B-NHLs was paralleled by Bcl-6 and c-Myc downregulation. In vitro and in vivo analysis of HSPH1-silenced Namalwa cells showed that this effect was associated with a significant growth delay and the loss of tumorigenicity when 104 cells were injected into mice. Interestingly, we found that HSPH1 physically interacts with c-Myc and Bcl-6 in both Namalwa cells and primary aggressive B-NHLs. Accordingly, expression of HSPH1 and either c-Myc or Bcl-6 positively correlated in these diseases. Our study indicates that HSPH1 concurrently favors the expression of 2 key lymphoma oncoproteins, thus confirming its candidacy as a valuable therapeutic target of aggressive B-NHLs.

Introduction

We have recently demonstrated that heat shock protein (HSP)H1/105 is a novel antigen and potential therapeutic target of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (B-NHLs). We showed that it is expressed in function of B-NHL aggressiveness, and its targeting by a specific antibody (Ab) provides significant therapeutic activity against human aggressive B-NHLs in vivo.1 We have now set out to clarify its role as a potential molecular target in these diseases.

High-grade B-NHLs—including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with its numerous subtypes, and Burkitt lymphoma (BL)—account for ∼60% of NHL cases.2 Despite their high response rate to anti-CD20 rituximab-based chemoimmunotherapy, alternative strategies are required to manage relapse and resistance, which still pose a very high risk of death in approximately one-third of cases.3 Sustained expression of Bcl-6 or c-Myc oncoprotein is the best-recognized trait of DLBCL4 or BL,5 respectively, whereas their concurrent overexpression defines a subset of aggressive B-NHLs with an extremely unfavorable prognosis.6 Although these transcription factors (TFs) have long been regarded as reliable lymphoma targets,7,8 their selective inhibition has proven challenging. To ensure constitutive high expression of key oncoproteins, NHLs have shown to upregulate HSP90 and HSP70,9,10 which assist protein folding and prevent protein degradation.11 Investigation of HSP90 inhibitors has thus been extended to lymphoma patients.12

Here we provide evidence that HSPH1 constitutes a viable alternative therapeutic target of aggressive B-NHLs insofar as the in vitro and in vivo antilymphoma activity determined by its knockdown is strongly associated with both Bcl-6 and c-Myc downmodulation. The physical interaction of HSPH1 with Bcl-6 and c-Myc indicates that it may act as a crucial facilitator of lymphoma growth by favoring the expression of key oncoproteins. Our study thus provides the rationale for developing HSPH1 inhibitors as a new therapy for aggressive B-NHLs.

Study design

HSPH1 silencing

HSPH1 was silenced by lentiviral transduction of a human HSPH1-microRNA–encoding pcDNA™6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR vector (BLOCK-iT Lentiviral Pol II miR RNA expression kit, Invitrogen). Namalwa and Raji BL, and SU-DHL-4 and Karpas422 DLBCL cell lines (DMSZ) were transduced with HSPH1-microRNA or MOCK vector at a MOI of 5 and selected with 10 μg/mL blasticidin (Sigma-Aldrich). GFP+ cells were sorted on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences).

Western blot and immunoprecipitation

These were performed as described1 with the following anti-human Abs: anti-HSPH1/105 (Santa Cruz), anti-HSP90, and anti-HSP70 (Stressgen); anti-BiP/Grp78, anti-c-Myc, anti-phospho(Ser392)-p53, anti-STAT3, and anti-phospho-STAT3 (Cell Signaling); anti-Bcl-6, anti-p53, and anti-phospho(Ser15)-p53 (Dako, Denmark); and anti-actin and anti-vinculin (Sigma-Aldrich).

In vivo experiments

Six-to-eight-week-old severe combined immunodeficiency mice (SCID, Charles River) were injected subcutaneously with 106 or 104 Namalwa cells and monitored for tumor growth. Experimental protocols were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation of Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale per lo Studio e la Cura dei Tumori (Milan, Italy) according to the Italian legislation (Legislative Order No. 116 of 1992, as amended), which implements the EU 86/109 Directive.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Tissue sections from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor xenografts and primary human B-NHLs obtained from our Institutional Tissue Bank were treated as described1 and incubated overnight with anti-human HSPH1, Bcl-6 (Dako), CD31 (Novocastra), or c-Myc (Epitomics) Abs. Expression of HSPH1, c-Myc, and Bcl-6 was quantified by a combining score as reported.1 The Independent Ethics Committee of our institutions approved molecular characterizations of patients’ material. Two-step double-marker immunofluorescence analysis was performed as described.13

Results and discussion

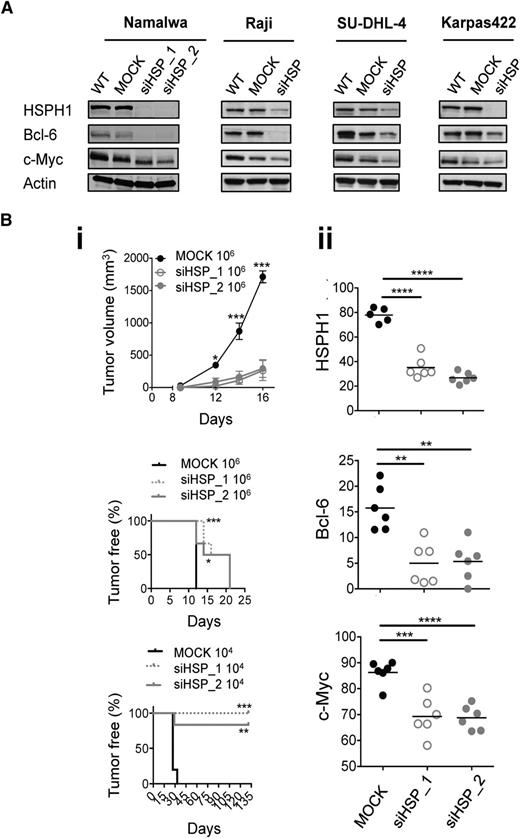

To clarify HSPH1’s functional role in aggressive B-NHLs, we first analyzed the molecular consequences of its silencing in 2 BL and 2 DLBCL cell lines. HSPH1 knockdown was consistently associated with the downregulation of c-Myc and Bcl-6 (Figure 1A). Further characterization of 2 HSPH1-silenced (siHSPH1_1 and siHSPH1_2) Namalwa cultures vs the MOCK counterpart revealed a significant proliferation delay and increased doubling time (supplemental Figure 1A), but not enhanced cell death (not shown) nor any reduction in expression or activation status of the previously reported HSPH1 client proteins STAT314 and p53,15,16 or other HSP-family–related members17 (supplemental Figure 1B). This supported the specific relationship between downregulation of HSPH1, c-Myc, Bcl-6, and antilymphoma effects. Accordingly, SCID mice xenografted with 106 siHSPH1 Namalwa cells displayed a significantly prolonged tumor-free survival and developed significantly smaller tumors (Figure 1Bi), in which Bcl-6, c-Myc, and HSPH1 were still consistently downmodulated (Figure 1Bii and supplemental Figure 2). Intriguingly, when 104 cells were injected, 0 of 6 and 1 of 6 lesions appeared over 131-day observation in siHSPH1_1 or siHSPH1_2 implanted mice, respectively, whereas palpable tumors were always present 33 days after injection of the MOCK cells (Figure 1Bi, bottom). In the presence of a very few lymphoma cells where HSPH1 is inhibited and Bcl-6 and c-Myc downregulated, the amount of growth factors required to sustain lymphoma engraftment may not be efficiently produced. Because HSPs,18,19 including HSPH1,20 sustain tumor neovascularization, and the role c-Myc in promoting this process is well-established,21,22 we hypothesized that HSPH1 silencing counteracts tumor angiogenesis by multiple sides, thus hampering in vivo engraftment. Quantification of the CD31+ endothelial area in siHSPH1 and MOCK Namalwa xenografts showed that it was significantly affected by HSPH1 silencing (supplemental Figure 2), thus explaining the differential antilymphoma effects observed in vitro and in vivo.

Antilymphoma effects of HSPH1 silencing in human aggressive B-NHL models. (A) Western blot analyses of HSPH1, Bcl-6, c-Myc, and actin as internal protein-loading control in the indicated wild-type (WT), MOCK, and siHSPH1 (siHSP) human aggressive B-NHL cell lines. Western blot images were acquired using Microtek ArtixScan F1 and cropped to retain the relevant bands with Adobe Photoshop CS version 4 for Macintosh computer. (B) Tumor growth curve (top) and tumor-free survival (middle, bottom) of SCID mice injected subcutaneously with 106 or 104 MOCK, siHSP_1, and siHSP_2 cells (6/group) (i). Tumor volume was calculated as 0.5 × d12 × d2 (d1, smaller diameter; d2, larger diameter). Statistically significant differences were calculated by using the 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest or the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, respectively (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). (ii) Quantitative software analyses of HSPH1, Bcl-6, and c-Myc expression evaluated by immunohistochemistry in MOCK, siHSP_1, and siHSP_2 xenografts 16 days after injection of 106 cells. Data are shown as mean ± standard of the mean of the ratio between the immunostained area and the total nuclear area, measured by ImageJ software analysis v.146 in 3 to 5 high-power microscopic fields for each case. Significant differences were calculated with the unpaired 2-tailed Student t test (**P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001).

Antilymphoma effects of HSPH1 silencing in human aggressive B-NHL models. (A) Western blot analyses of HSPH1, Bcl-6, c-Myc, and actin as internal protein-loading control in the indicated wild-type (WT), MOCK, and siHSPH1 (siHSP) human aggressive B-NHL cell lines. Western blot images were acquired using Microtek ArtixScan F1 and cropped to retain the relevant bands with Adobe Photoshop CS version 4 for Macintosh computer. (B) Tumor growth curve (top) and tumor-free survival (middle, bottom) of SCID mice injected subcutaneously with 106 or 104 MOCK, siHSP_1, and siHSP_2 cells (6/group) (i). Tumor volume was calculated as 0.5 × d12 × d2 (d1, smaller diameter; d2, larger diameter). Statistically significant differences were calculated by using the 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest or the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, respectively (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). (ii) Quantitative software analyses of HSPH1, Bcl-6, and c-Myc expression evaluated by immunohistochemistry in MOCK, siHSP_1, and siHSP_2 xenografts 16 days after injection of 106 cells. Data are shown as mean ± standard of the mean of the ratio between the immunostained area and the total nuclear area, measured by ImageJ software analysis v.146 in 3 to 5 high-power microscopic fields for each case. Significant differences were calculated with the unpaired 2-tailed Student t test (**P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001).

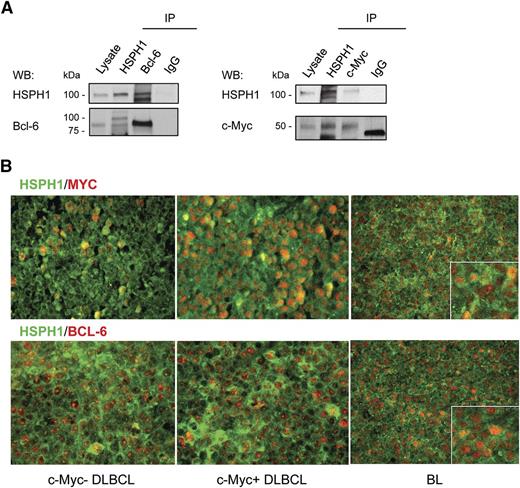

To understand how HSPH1 inhibition could lead to c-Myc and Bcl-6 downregulation, we tested whether they interacted with HSPH1 and thus might constitute HSPH1 client proteins, as was already described for Bcl-6 and HSP90.9 According to our hypothesis, both Bcl-6 and c-Myc coimmunoprecipitated with HSPH1 from Namalwa-cell lysate (Figure 2A). This was confirmed in primary human aggressive B-NHLs by the in situ demonstration of HSPH1 paralleling Bcl-6 and c-Myc distribution (supplemental Figure 3A). On the basis of similar Bcl-6 contents in these specimens, a higher c-Myc expression was associated with even higher HSPH1 levels (supplemental Figure 3A), further supporting the requirement of HSPH1 to maintain high expression levels of these TFs. Double-marker immunofluorescence highlighted nuclear colocalization between HSPH1 and either c-Myc or Bcl-6 in primary human DLBCLs and BLs (Figure 2B). This indicates that HSPH1 may chaperone both Bcl-6 and c-Myc in B-NHLs, and that their reduced expression in siHSPH1 cells may be a direct consequence of HSPH1 downregulation. Accordingly, in 32 primary human aggressive B-NHL cases (11 BLs; 10 DLBCLs; 8 grade 3 follicular lymphomas; 3 mantle cell lymphomas), in which HSPH1, Bcl-6, and c-Myc were all evaluable by immunohistochemistry (of 45 analyzed), HSPH1 levels directly correlated with those of Bcl-6 and c-Myc (P < .0001 and P = .0002, respectively; Pearson correlation analysis), pointing to a new characteristic of aggressive B-NHLs to express these molecules at proportional levels (supplemental Figure 3B). Furthermore, DLBCLs expressing c-Myc also expressed significantly higher levels of HSPH1 compared with c-Myc low/negative DLBCLs (supplemental Figure 3C).

HSPH1 interaction with c-Myc and Bcl-6 in human aggressive B-NHLs. (A) Western blot analyses of HSPH1 and Bcl-6 (left) or HSPH1 and c-Myc (right) in Namalwa whole-protein extract immunoprecipitated (IP) with Abs against the indicated molecules or control isotype IgG. Whole lysate was included as an internal control. For c-Myc immunoprecipitation, proteins were eluted in nonreducing condition to avoid the detection of Ab heavy chains in the region in which c-Myc protein migrates. Western blot images were acquired using Microtek ArtixScan F1 and cropped to retain the relevant bands with Adobe Photoshop CS version 4 for Macintosh computer. (B) Representative microphotographs of double-marker immunofluorescence for HSPH1 (green signal) and either Bcl-6 or c-Myc (red signal) in 2 cases of germinal center–type DLBCLs with (middle) or without (left) c-Myc amplification, and 1 case of BL (right). Bindings of primary rabbit anti-human HSPH1 Ab and mouse anti-human Bcl-6 (clone PG-B6p) or anti-human c-Myc (clone 9E10) were revealed, respectively, by an Alexa-488– and an Alexa-568–conjugated secondary Abs. Sections were analyzed under a Leica DMRBE microscope and microphotographs were collected with a Leica MC120HD digital camera.

HSPH1 interaction with c-Myc and Bcl-6 in human aggressive B-NHLs. (A) Western blot analyses of HSPH1 and Bcl-6 (left) or HSPH1 and c-Myc (right) in Namalwa whole-protein extract immunoprecipitated (IP) with Abs against the indicated molecules or control isotype IgG. Whole lysate was included as an internal control. For c-Myc immunoprecipitation, proteins were eluted in nonreducing condition to avoid the detection of Ab heavy chains in the region in which c-Myc protein migrates. Western blot images were acquired using Microtek ArtixScan F1 and cropped to retain the relevant bands with Adobe Photoshop CS version 4 for Macintosh computer. (B) Representative microphotographs of double-marker immunofluorescence for HSPH1 (green signal) and either Bcl-6 or c-Myc (red signal) in 2 cases of germinal center–type DLBCLs with (middle) or without (left) c-Myc amplification, and 1 case of BL (right). Bindings of primary rabbit anti-human HSPH1 Ab and mouse anti-human Bcl-6 (clone PG-B6p) or anti-human c-Myc (clone 9E10) were revealed, respectively, by an Alexa-488– and an Alexa-568–conjugated secondary Abs. Sections were analyzed under a Leica DMRBE microscope and microphotographs were collected with a Leica MC120HD digital camera.

Our results indicate that HSPH1 constitutes a functional target of aggressive B-NHLs, including those DLBCLs with the most unfavorable prognosis, as a result of its facilitation of the expression of Bcl-6 and c-Myc, 2 of their most commonly deregulated oncoproteins.

Involvement of HSPH1 nuclear β isoform24 in TF activation17 indicates that it may similarly favor Bcl-6 and c-Myc activity by stabilizing their expression on their target genes, as was already described for HSP90 and Bcl-6.9

The lack of effective strategy to directly inhibit either Bcl-6 or c-Myc further highlights the significance of our findings. In view of the relatively higher HSPH1 expression in B-NHLs and their dependency on c-Myc and/or Bcl-6 to grow, inhibition of HSPH1 may selectively target lymphoma cells and favors their response to standard treatments, hence leading the way to more effective therapeutic combinations.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by research funding from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (IG14347, Milan, Italy) and Fondazione Michelangelo (Milan, Italy) (M.D.N.); and a fellowship from the Associazione Marco Semenza (Milan, Italy) (R.Z.).

Authorship

Contribution: R.Z., S.M.P., A.M.G., F.D.B., and M.D.N. designed the research and wrote the paper; R.Z., G.R., A.C., M.T., C.G., C. Tringali, A.D.C., L.C., B.V., N.Z., and C. Tripodo performed experiments; and R.Z., S.M.P., and M.D.N. analyzed data and compiled the figures.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Massimo Di Nicola, Via Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy; e-mail: massimo.dinicola@istitutotumori.mi.it; and Roberta Zappasodi, Via Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy; e-mail: roberta.zappasodi@istitutotumori.mi.it.