In this issue of Blood, Abrahamsson et al have described a real-world scenario for the front-line treatment of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).1 Medical knowledge in hematologic malignancies is based on currently available data, preferably from prospective trials; however, these data are limited by recruitment of fit, predominantly younger patients in most trials. Thus, additional data on a more representative patient population, including elderly patients, are urgently needed.

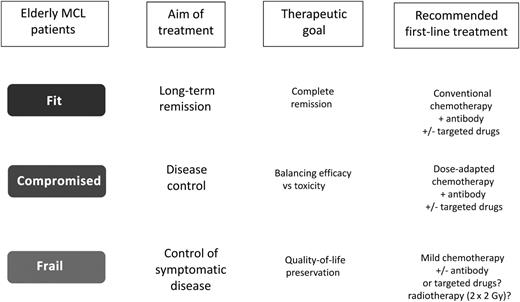

Therapeutic recommendations for elderly MCL patients according to geriatric assessment.

Therapeutic recommendations for elderly MCL patients according to geriatric assessment.

Data from national registries were collected for more than a decade, with 1389 patients with MCL identified. The data confirmed the favorable prognosis of both patients with localized stage I/II treated with curative intent as well as patients with a more indolent presentation who were treated using a watchful-waiting approach.2 It is reassuring that clinical risk scores and benefits of dose-intensified approaches in younger patients have been confirmed in this large series.3,4 However, with a median age of 71 years and two-thirds of patients >65 years, patients in this study were predominantly elderly. In a recent study of an elderly patient population, excellent long-term survival rates were reported using a conventional immunotherapy.5 Similarly, another large European trial has reported long-term remissions approaching the results achieved with indolent lymphoma.

In both of these studies, median age was about 70 years, similar to the current report. However, the patient populations differ significantly, as only fit elderly patients qualified for prospective trials due to restrictive inclusion criteria. Also, in the current survey, treatment approaches varied over a broad range, from autologous stem cell transplantation to chlorambucil only.

So how should we set up a really “personalized” treatment strategy based on biological age, comorbidities, and general performance status? Ageing and age-related problems are aspects of significant impact in routine clinical practice. Modern treatment paradigms, including the integration of monoclonal antibodies, rediscovered old drugs such as bendamustine, and, more recently, inhibitors of the B-cell receptor signal pathway into the treatment algorithm, undeniably provide unprecedented response rates even in relapsed/refractory MCL.5-7 However, it is important to acknowledge that, so far, significant lifespan improvements have been observed among younger and elderly fit patients. Unfit or frail subjects benefit much less from such innovations, due to limited access (exclusion from clinical trials), impaired tolerance of side effects, or potentially suboptimal efficacy of these drugs in older individuals. In addition, the increasing number of elderly patients successfully but “chronically” treated for several years raises a host of economic and social questions. What is the real impact of malignancies becoming chronic illnesses? How long should these patients be treated?

Given all these considerations, we have to realize that, despite remarkable advances during the last few years, we still need to address aging with a more comprehensive strategy. In fact, we have to keep in mind that elderly people are a very heterogeneous population, regardless of chronological age, ranging from active, fully autonomous individuals to frail and dependent ones. Thus, the biological age may be highly variable, relying on multiple factors such as comorbidities and economic, educational, social, and family conditions. From a practical point of view, a comprehensive geriatric assessment is a useful tool for estimating life expectancy and tolerance of treatment; moreover, it helps to identify reversible factors that may interfere with cancer treatment, including depression, malnutrition, anemia, neutropenia, and limited caregiver support.8 Applying some practical tools (mainly questionnaires), elderly patients can be divided accordingly in 3 geriatric groups (see figure):

For the “fit” patients, the treatment goal should be the achievement of complete remissions with potential long-term remissions. Therefore, a conventional immunochemotherapy (bendamustine plus rituximab [BR]; cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone plus rituximab) followed by rituximab maintenance is recommended.6 At relapse, regimens containing non–cross-reactive drugs plus or minus targeted drugs, preferably within clinical trials, are advisable.

For the “compromised” patients, the treatment should aim at the control of the disease. However, efficacy has to be balanced against expected toxicities, as underlying comorbidities or impaired organ function may compromise the tolerability of standard approaches. Thus, dose-adapted chemotherapy schemes (eg, 2-4 times BR) plus or minus targeted drugs may be recommended.

For “frail” patients, preservation of quality of life should remain the primary objective. Therefore, mild (basically oral) chemotherapy schemes are recommended (eg, chlorambucil; prednisone, etoposide, procarbazine, and cyclophosphamide).

It is tempting to speculate if the latter patient subset may benefit from targeted approaches because of their high response rate and favorable safety profile. Clinical trials investigating first-line “chemotherapy-free” regimens tailored for elderly unfit or frail patients are lacking, but they are urgently needed. Effective and well-tolerated schemes might be based on the combination of targeted agents with mild cytostatics, as already demonstrated in multiple myeloma. Only systematic studies will enable us to offer a more individualized approach to elderly patients with MCL.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal