Key Points

Clonal B-cell lymphocytosis of potential marginal-zone origin (CBL-MZ) rarely progresses to a well-recognized lymphoma.

CBL-MZ does not require treatment in the absence of progressive disease.

Abstract

The biological and clinical significance of a clonal B-cell lymphocytosis with an immunophenotype consistent with marginal-zone origin (CBL-MZ) is poorly understood. We retrospectively evaluated 102 such cases with no clinical evidence to suggest a concurrent MZ lymphoma. Immunophenotyping revealed a clonal B-cell population with Matutes score ≤2 in all cases; 19/102 were weakly CD5 positive and all 35 cases tested expressed CD49d. Bone marrow biopsy exhibited mostly mixed patterns of small B-lymphocytic infiltration. A total of 48/66 (72.7%) cases had an abnormal karyotype. Immunogenetics revealed overusage of the IGHV4-34 gene and somatic hypermutation in 71/79 (89.8%) IGHV-IGHD-IGHJ gene rearrangements. With a median follow-up of 5 years, 85 cases remain stable (group A), whereas 17 cases (group B) progressed, of whom 15 developed splenomegaly. The clonal B-cell count, degree of marrow infiltration, immunophenotypic, or immunogenetic findings at diagnosis did not distinguish between the 2 groups. However, deletions of chromosome 7q were confined to group A and complex karyotypes were more frequent in group B. Although CBL-MZ may antedate SMZL/SLLU, most cases remain stable over time. These cases, not readily classifiable within the World Heath Organization classification, raise the possibility that CBL-MZ should be considered as a new provisional entity within the spectrum of clonal MZ disorders.

Introduction

The 2008 World Heath Organization (WHO) classification of hematologic malignancies utilizes clinical, morphologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic data to define distinct and provisional entities based on cell lineage.1 The 2008 version of the classification and a subsequent perspective2 recognized the increasing detection of small B-cell clones both in the blood and tissues and the uncertainty surrounding their biological and clinical significance.

In 2005, the term monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL) was introduced to describe the presence of circulating small B-cell clones of <5 × 109/L persisting for more than 3 months in healthy individuals who had no evidence of lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, an associated autoimmune disease, or any other feature diagnostic of a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder other than the presence of a paraprotein.3,4 MBL encompasses the very small clones detectable in individuals5 with a normal lymphocyte count (population MBL)5 as well as larger clones detectable in patients presenting with a slight lymphocytosis (clinical MBL).6

MBL was subclassified into a CD5 +ve, CD23 +ve CLL-like category; a CD5 +ve, CD23 −ve, CD20bright atypical CLL category; and a CD5 −ve category.3,4 Many subsequent studies have confirmed the biological similarities between clinical CLL-like MBL and early stage CLL7 and the low rate of progression to CLL requiring therapy.8,9 Although the diagnostic criteria for CLL-like clinical MBL have been used to refine the diagnosis of CLL, the cutoff of 5 × 109/L3,4 clonal B lymphocytes for distinguishing clinical MBL from CLL is arbitrary, lacking clinical and/or biological justification.

While the “atypical −CLL” variant of MBL is recognized to include cases of indolent mantle cell lymphoma,10,11 the nature of CD5 −ve MBL remains unclear. Furthermore, although very small B-cell clones carrying the t(14;18) translocation detectable by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can frequently be found in the blood of healthy individuals12 and follicular lymphoma in situ is a well recognized entity,13 it is extremely rare for CD5 −ve clinical MBL to show the immunophenotypic or genetic features of a germinal-center–derived clonal B-cell disorder.14 In contrast, many cases of CD5 −ve clinical MBL have immunophenotypic and morphologic features typically associated with marginal-zone (MZ) lymphomas involving the spleen.15 In fact, early studies on splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes, now regarded as a leukemic manifestation of a MZ splenic lymphoma, included cases with circulating villous lymphocytes in the absence of splenomegaly that either pursued an indolent course or subsequently developed splenic enlargement.16

Uncertainty about the biological significance of CD5 −ve clinical MBL also extends to its clinical management. Whereas the clinical relationship between CLL-like MBL and early CLL is well understood and neither bone marrow (BM) examination nor imaging studies are recommended in the former at diagnosis,17,18 it is still not clear whether those investigations are mandatory in clinical CD5 −ve MBL diagnosis.

In view of this clinical and biological uncertainty, we have reviewed the morphologic, clinical, cytogenetic, and immunogenetic features of cases presenting predominantly with a lymphocytosis, or more rarely with a paraprotein and normal lymphocyte count, whose immunophenotype was consistent with an MZ lymphoma. We provide data to suggest that at least a proportion of these cases are not readily classifiable according to the current WHO or MBL criteria and discuss whether there is sufficient evidence to warrant the introduction of a new term such as clonal B-cell lymphocytosis with MZ features (CBL-MZ) as a provisional entity.

Patients and methods

Patients

This retrospective study included 102 patients from 3 centers selected on the basis of the demonstration of a clonal B-cell population with immunophenotypic features consistent with MZ derivation yet without lymphadenopathy, signs of chronic and/or active inflammation, autoimmunity, organomegaly, or cytopenias (Table 1). Clonal B-cell populations were identified during the investigation of a persistent (>6 months) lymphocytosis of >3.0 × 109/L or paraproteinemia. Information regarding patient demographics and clinical presentation is given in “Results.”

Demographics and basic laboratory test results of the patients included in the present cohort

| Number of cases | 102 |

| Men/Women | 49/53 |

| Age | Δm: 71 y (range: 38-91 y) |

| Lymphocyte count | Δm: 6.63 × 109/L (range: 2.2-37.1 × 109/L) |

| Hemoglobin count | Δm: 136.5 g/L (range: 116-177 g/L) |

| Platelet count | Δm: 239 × 109/L (range: 145-524 × 109/L) |

| Paraproteinemia | 27/81 cases (33%) |

| Number of cases | 102 |

| Men/Women | 49/53 |

| Age | Δm: 71 y (range: 38-91 y) |

| Lymphocyte count | Δm: 6.63 × 109/L (range: 2.2-37.1 × 109/L) |

| Hemoglobin count | Δm: 136.5 g/L (range: 116-177 g/L) |

| Platelet count | Δm: 239 × 109/L (range: 145-524 × 109/L) |

| Paraproteinemia | 27/81 cases (33%) |

Δm, median value.

The study was approved by the ethics review committee of each participating institution. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical evaluation

A detailed medical history and physical examination were available for all patients. The majority were screened by serum immunoelectrophoresis for the presence of hypogammaglobulinemia and a paraprotein, for the hepatitis C virus, and also underwent computed tomography scanning of the chest and abdomen and/or ultrasonography of abdominal organs (including the spleen). Gastroscopy, with concurrent mucosal biopsies and BM examination, was performed on selected patients at the discretion of each center.

Blood and BM smear morphology

Blood and BM smears were morphologically evaluated for the presence of clonal lymphocytes after staining with the May-Grunwald/Giemsa technique.

Immunophenotyping of lymphomatous cells in the blood and BM aspirate

Clonal lymphocytes in the blood and/or BM were immunophenotypically studied by flow cytometry using standard techniques. In the panel of this immunophenotyping study, the following monoclonal antibodies were used: κ and λ clonality, CD19, CD20, CD5, CD10, CD23, CD79b, FMC7, CD38, and CD49d.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical studies

BM biopsy samples were obtained at diagnosis based on the policy of the participating center from 35 cases and reviewed by experienced hematopathologists (T.P. and P.K.). Tissue processing and immunohistochemistry were performed as previously described.17

Cytogenetic studies

Cytogenetic studies were performed at diagnosis on peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells as previously described.19 Karyotypes were described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN, 2005).20 Cutoffs used for chromosome gain, loss, or rearrangement were 5%, 10%, and 5%, respectively. A karyotype was defined as complex when ≥3 chromosomal aberrations were observed (structural and/or numerical).

Individual patient cases were analyzed in the Mitelman database (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov). Ideograms of translocation breakpoints, gains, and losses of chromosomal material in the studied cohort were prepared with the use of the Cydas software (freely available at http://www.cydas.org).

PCR amplification, sequence analysis, and sequence interpretation of IGHV-IGHD-IGHJ rearrangements

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or genomic DNA-PCR amplification of IGHV-IGHD-IGHJ rearrangements was performed as previously described.21,22

Purified PCR amplicons were directly sequenced on both strands. Sequence data were analyzed using the international IMGT database23 and the IMGT/V-QUEST tool24 (http://www.imgt.org).

Statistical analysis and definitions

Descriptive statistics were used for the presentation of data in terms of frequency distributions (discrete variables) and mean, median values (quantitative variables). All analyses were performed at a significance level of 5% with the statistical package SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL).

Results

Overview of the patient cohort

The present series included 102 cases, 49 men and 53 women, retrospectively selected for the presence of a clonal B-cell population with immunophenotypic features consistent with MZ derivation (Table 1). In all cases, physical examination was negative for lymphadenopathy and/or organomegaly and this was further confirmed by radiologic assessment. No concurrent cytopenias were observed in any of the studied cases. None had any clinical or laboratory features to indicate a diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma, hairy cell leukemia, follicular lymphoma, or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The median age at presentation was 71 years (range, 38-91 years). Eighty of 102 (78.4%) cases presented with a lymphocytosis of >4.0 × 109/L (median lymphocyte count: 6.63 × 109/L; range: 4.0-37.1 × 109/L) and 13 cases (12.7%) with a lymphocyte count between 3.0 and 3.97 × 109/L (median 3.7 × 109/L) detected incidentally on a routine blood test. In 9 cases (8.8%), all with normal complete blood count, a clonal lymphocytic population was identified during the evaluation of paraproteinemia.

Of 81 cases with available information, 27 were positive for serum paraprotein (median level: 0.7 g/dL, range: 0.3-3.8 g/dL). Data concerning the type of paraprotein were available in 25 cases, as follows: immunoglobulin Gκ, n = 8; immunoglobulin Gλ, n = 4; immunoglobulin Mκ, n = 9; immunoglobulin Mλ, n = 4. None of the studied cases with available data (87/102) had positive serology for the hepatitis C virus.

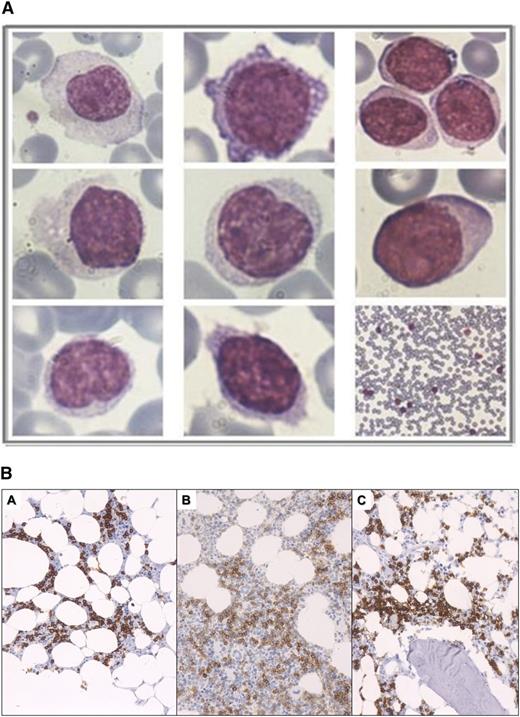

Blood smear lymphocyte morphology

Examination of May-Grunwald/Giemsa–stained PB smears revealed a heterogeneous lymphocytic population consisting of small, medium, and large cells (Figure 1A). Cytoplasm was variable in amount. Nuclei were round to oval, centrally or eccentrically placed, with dense or sparse chromatin. Variable numbers of villous lymphocytes and lymphocytes with plasmacytoid differentiation were identified in some cases. Overall, although morphologic heterogeneity of the lymphocytic population was evident in all cases, the cytologic features of different cases were generally similar.

Peripheral blood cytology and BM pathology. (A) Peripheral blood smear lymphocyte cytology. Morphologic heterogeneity of the lymphocytic population was apparent in most CBL-MZ cases. (B) Patterns of BM lymphocytic infiltration by predominately small B-lymphocytes showing interstitial with minor extent of intrasinusoidal pattern of infiltration (A), interstitial pattern of infiltration (B), and paratrabecular and interstitial pattern of infiltration (C). In all images, B cells are depicted with the CD20 antibody.

Peripheral blood cytology and BM pathology. (A) Peripheral blood smear lymphocyte cytology. Morphologic heterogeneity of the lymphocytic population was apparent in most CBL-MZ cases. (B) Patterns of BM lymphocytic infiltration by predominately small B-lymphocytes showing interstitial with minor extent of intrasinusoidal pattern of infiltration (A), interstitial pattern of infiltration (B), and paratrabecular and interstitial pattern of infiltration (C). In all images, B cells are depicted with the CD20 antibody.

Immunophenotypic findings by flow cytometry

In all cases, PB immunophenotyping by flow cytometry revealed the presence of a clonal B-cell population with a Matutes score 0 to 2. Cells from all cases expressed B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20 strong), whereas they were consistently negative for the expression of CD10. Other individual markers were expressed as follows: CD5, 19/102 cases (18.6%); CD23, 16/102 cases (15.6%); CD79b, 77/85 cases (90.5%); FMC7, 74/93 cases (79.5%); and CD38, 6/53 cases (11.3%). Intriguingly, all 35 analyzed cases expressed CD49d.

Only 2 cases exhibited coexpression of CD5 and CD23, both with a Matutes score of 2.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings

In all 35 BM biopsy specimens studied at presentation, a lymphocytic infiltration was found, ranging from 7% (single case) to >70%; 17 of 35 cases (48.5%) exhibited ≥30% BM lymphocytic infiltration. No clear association was observed between the extent of BM lymphocytic infiltration and the PB lymphocyte count.

Most cases exhibited mixed patterns of predominantly interstitial and, to a lesser extent, nodular or intrasinusoidal infiltration (Figure 1B). In 27 of 35 cases, the lymphoid infiltrate consisted of small cells with a round-to-oval nucleus and clumped chromatin. In 5 cases, a proportion of the small B-lymphocytic infiltration exhibited plasmacytoid differentiation.

In all cases, immunohistochemistry showed that the lymphocytic infiltrate was immunoreactive for CD20 and CD79a, while it was consistently negative for CD10, CD3, Bcl-6, and cyclin D1. A total of 1 and 4 cases expressed CD5 and CD23, respectively, whereas no case exhibited coexpression of CD5 and CD23. DBA44 was positive in 7/21 (33.3%) cases.

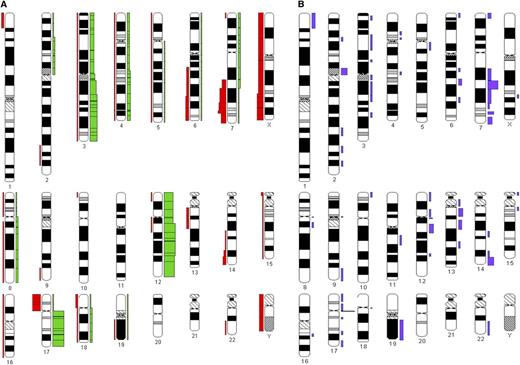

Cytogenetic findings

Among 67 cases analyzed by G-banding cytogenetics, 48 (71.6%) displayed an aberrant karyotype (Figure 2). Within this subgroup, 11 (22.9%) cases carried 3 or more cytogenetic abnormalities and were considered to exhibit a complex karyotype. The chromosomes most frequently involved were 3, 12, 17, and 7. Aberrations with involvement of chromosome 7 included del(7q) (n = 7 [14.5%]) as well as translocations involving 7q [n = 6 (12.5%), of which 3 concerned a t(2;7)(p11;q22)]. Isochromosome 17q was identified in 8 (16.6%) cases; in 3 of 8 cases, this was the sole aberration.

Graphic representation of the cytogenetic findings. The ideograms were prepared with the CYDAS software package, freely available at www.cydas.org. (A) Additions (green) and deletions (red). (B) Chromosomal translocation breakpoints.

Graphic representation of the cytogenetic findings. The ideograms were prepared with the CYDAS software package, freely available at www.cydas.org. (A) Additions (green) and deletions (red). (B) Chromosomal translocation breakpoints.

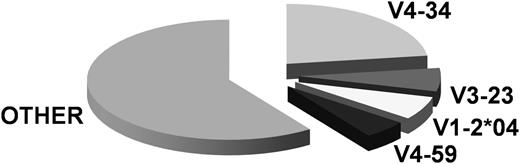

Immunogenetics

A total of 79 productive IGHV-IGHD-IGHJ rearrangements were obtained from 77 analyzed cases, because 1 case each carried 2 and 3 productive rearrangements, respectively. In the latter case, exhibiting a uniform immunophenotype, the most plausible explanation is biclonality (ie, the presence of 2 MZ-like populations).

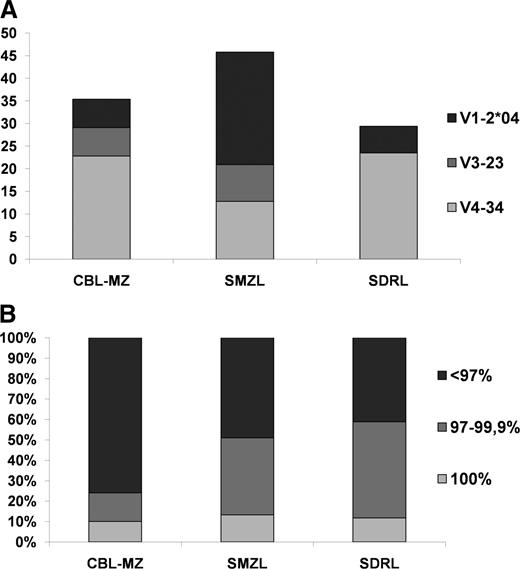

Overall, 28 different IGHV genes were identified. The IGHV4-34 gene predominated (18/79 rearrangements, 22.8%), followed by the IGHV3-23 (5 of 79, 6.3%), IGHV1-2 (5/79, 6.3%) and IGHV4-59 (4/79, 5%) genes (Figure 3). Concerning somatic hypermutation (SHM), 8/79 rearrangements (10.1%) carried IGHV genes with no SHM (100% identity to the germline) and were assigned to a “truly unmutated” subgroup. The remainder (71/79, 89.8%) showed some impact of SHM activity, ranging from minimal to pronounced. For statistical comparisons, sequences with 97% to 99.9% gene identity to the germline were classified as “borderline/minimally mutated” (n = 11/79, 13.9%), whereas those with <97% identity to the germline as “significant mutated” (n = 60/79, 75.9%).

Clinical outcomes

With a median follow-up of 5 years (range: 0.4-20.2 years), 85 cases exhibited isolated MZ-like lymphocytosis without organ involvement (group A). The remaining 17 cases were classified separately (group B) because they evolved clinical signs and/or had laboratory/imaging findings consistent with/suggestive of a well-recognized lymphoma entity. Signs of progression were noted at a median of 24 months from diagnosis (range: 8-79 months). In particular, (1) 15 cases developed progressive enlargement of the spleen, assessed both clinically and radiologically, with no cytopenias or lymphadenopathy (in such cases, a diagnosis of splenic marginal-zone lymphoma [SMZL] or splenic lymphoma/leukemia unclassifiable [SLLU] is a definite possibility; however, this could not be formally established because no case underwent splenectomy); (2) 1 case was eventually diagnosed with gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (see below); and (3) 1 case developed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of the skin; the clonal relationship of the DLBCL with the preexisting MZ-like lymphocytosis could not be investigated due to the inability to obtain by PCR the clonotypic IGHV-IGHD-IGHJ gene rearrangement of the DLBCL, likely because of technical reasons (formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded material yielding low-quality DNA).

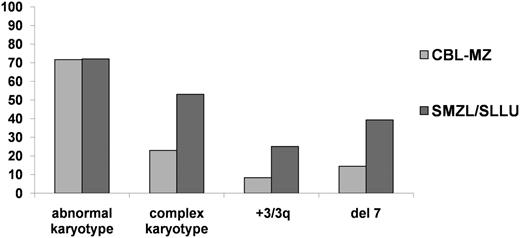

A comparison of group A and group B showed no differences with regards to age, gender, lymphocyte count, incidence of paraproteinemia, immunophenotype, frequency of infection by Helicobacter pylori (HP), IGHV gene repertoire, and mutational status. In contrast, the cytogenetic profiles of the 2 groups were distinct. In particular, (1) del7q was identified exclusively among group A cases, (2) i(17q) as single aberration and/or coexisting with other aberrations predominated in group A (7/50 vs 1/17 group B cases, respectively), (3) a complex karyotype was less frequent in group A compared with group B (6/50 vs 5/17 cases, respectively), and (4) translocation t(2;7)(p11;q22) was only identified in group B cases. Interestingly, of 5 group B cases with karyotypic complexity, 4 belonged to the “possible SMZL/SLLU” category. The differences between groups A and B regarding i(17q) and karyotype complexity did not reach statistical significance (P values of .3 and .09, respectively), likely due to small numbers.

In very rare cases, MZ-like lymphocytosis can be the presenting feature of occult gastric MALT lymphoma

We have previously reported that MZ-like lymphocytosis can be the presenting feature of occult gastric MALT lymphoma.25,26 To exclude this possibility in the current series, a subset of 34 cases of the present cohort were subjected to upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy. All cases but one had no endoscopic or histopathological evidence of lymphoma; 21/33 cases were found with gastritis, and among them 10 were HP positive; 5 cases received HP eradication treatment and were HP negative with normal GI endoscopy on reevaluation. Lymphocytosis persisted in all 5 cases after HP eradication, indicating that the detection of HP may be a coincidental finding of no direct etiopathogenic significance.

The remaining case with GI endoscopic evaluation concerned an asymptomatic 74-year-old woman with MZ-like lymphocytosis who was diagnosed with gastric MALT lymphoma, t(11;18) negative, HP positive, 8 months after the initial presentation. The patient received HP eradication therapy followed by chlorambucil (12 cycles) and attained a complete remission, but the monoclonal lymphocytosis has persisted (46 months from the initial presentation). Molecular immunogenetic analysis of PB and gastric biopsy samples documented clonal identity of the circulating cells to the gastric MALT lymphoma (identical IGHV-IGHD-IGHJ rearrangements).

Discussion

We describe the presenting clinical and laboratory features and subsequent natural history of 93 patients presenting with a CD5 −ve lymphocytosis and a further 9 patients investigated for presence of a paraprotein. All had a circulating clonal B-cell population that was either CD5 negative or weakly CD5 positive. This was a retrospective collaborative study incorporating data from 3 centers. The diagnostic tests performed other than the core evaluation (namely clinical, morphologic, and immunophenotypic) varied upon each center’s policy. Even though this heterogeneity may be regarded as a weakness, suggesting that different centers may have studied different kinds of cases, the uniformity of the core evaluation findings leaves no doubt about the homogeneity of the study group.

All patients had a normal blood count apart from a lymphocytosis and had no clinical or radiologic evidence of lymphadenopathy or organomegaly. All had a circulating clonal B-cell population with an immunophenotype typically associated with MZ B cells. Interestingly, all evaluated cases expressed CD49d in the majority of cells together with a low frequency of CD38 expression. CD49d, the a4 integrin subunit, is critically implicated in microenvironmental interactions through the binding to fibronectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.27-30 In CLL, the CD49d/CD29 integrin complex is physically associated with CD38, being part of a macromolecular complex that impacts on migration and adhesion capacity, cell proliferation, and survival.29,31,32 In this context, the dissociation of CD49d from CD38 expression in the present series (at least for the great majority of cases) is noteworthy, but it is unclear whether the observed phenotype reflects the cell of origin or the neoplastic process.

The presence of villous lymphocytes, lymphocytes with plasmacytoid differentiation, an intrasinusoidal pattern of BM infiltration,33 and cytogenetic abnormalities of chromosome 7q34 observed in many cases of the present series are all seen in splenic MZ lymphomas35 and lend support to an MZ origin. Although none of the above features are pathognomonic of MZ lymphomas, our cohort did not have features to suggest alternative diagnoses. In particular, there were no morphologic, histologic, or cytogenetic data to indicate a germinal center origin or hairy cell leukemia and 0/45 cases evaluated had the MYD88 L265P mutation (unpublished data) closely associated with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia.36 Most cases pursued an indolent clinical course, but 15 developed splenomegaly detected clinically or radiologically, 1 additional case was subsequently diagnosed with a clonally related gastric MALT lymphoma, and 1 developed a cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma whose clonal relationship to the circulating clonal lymphocytes could not be established.

There are a number of possible and, in some cases, closely related explanations for the presence of a small circulating B-cell clone with an MZ phenotype in apparently healthy individuals. It could be (1) the leukemic manifestation of a preexisting undiagnosed lymphoma; (2) the early stage of a lymphoma with a high chance of clonal expansion and clinical progression given sufficient time; (3) the precursor of a lymphoma, requiring additional transforming events for disease progression; (4) a genomically stable clonal disorder with little of no risk of evolution to lymphoma; or (5) a heterogeneous group of patients including 2 or more of the above possibilities.

The 2008 WHO Classification recognized 3 distinct types of MZ lymphomas: (1) nodal MZ lymphomas, (2) extranodal MZ lymphomas of MALT type, and (3) SMZL as well as a broad category of variably well-defined provisional entities, involving primarily the spleen, that do not fall into any of the other distinct types of splenic B-cell neoplasms.1 The best-characterized provisional entities in this category of SLLU are hairy cell leukemia variant and splenic diffuse red pulp lymphoma (SDRL).

By definition, our cohort excluded cases with lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly but could have included cases with disease at extranodal sites such as the GI tract and BM. Gastroscopy, performed in 34 asymptomatic patients, revealed gastritis in 22 patients and a single gastric MALT lymphoma, detected 8 months after presenting with a lymphocytosis, consistent with the rarity of leukemic involvement in extranodal MZ lymphoma.25,37 In contrast, all cases showed clonal B-lymphocytic infiltration of the BM that was >30% in 17/35 patients. This raises the question as to whether these cases should be considered to have a MZ lymphoma of the BM.38 However, none presented with or developed cytopenias or have subsequently required treatment, and use of the term “lymphoma” to describe these cases would seem clinically inappropriate.

The observation that 15 patients developed splenomegaly strongly supports options 2 or 3, at least in a subset of cases. The absence of splenic histology limits the conclusions that can be drawn, although both cytogenetic and immunogenetic data provide some insights into the biology of MZ-like lymphocytosis. Among the whole cohort, the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities was 71.6%, identical to that seen in our recent large-scale multiinstitutional study of 330 cases of SMZL/SLLU.34 The pattern of cytogenetic abnormalities was also similar (Figure 4), with a high incidence of aberrations involving chromosome 7, including 3 cases with the t(2;7)(p11-12;q21-22) translocation leading to dysregulation of CDK6 expression. This translocation has been reported previously in rare cases of SMZL39 and a single case designated as CD5-negative MBL.40 Compared with SMZL/SLLU, MZ-like lymphocytosis exhibited a significantly lower frequency of complex karyotypic abnormalities (3 or more aberrations) and gain of chromosome 3/3q, but interestingly 4/5 cases with complex karyotypes developed splenomegaly, suggesting a link between clonal evolution and progressive disease. Eight patients, of whom 7 had stable disease, had an isochromosome of 17p resulting in TP53 loss. Several also had p53 dysfunction and a TP53 mutation (unpublished data), analogous to the findings in CD5 +ve MBL and early CLL, in which TP53 abnormalities may be associated with indolent disease, especially in patients with mutated IGHV genes.9,41

Comparison of main cytogenetic findings between CBL-MZ and primary splenic small B-cell lymphomas. CBL-MZ exhibits a heterogeneous cytogenetic profile that, apart from a similar incidence of abnormal karyotypes, is significantly different from both SMZL and splenic leukemia/lymphoma unclassifiable.34

Comparison of main cytogenetic findings between CBL-MZ and primary splenic small B-cell lymphomas. CBL-MZ exhibits a heterogeneous cytogenetic profile that, apart from a similar incidence of abnormal karyotypes, is significantly different from both SMZL and splenic leukemia/lymphoma unclassifiable.34

The immunogenetic signature of cases with MZ-like lymphocytosis reported in our study is strongly indicative of antigen selection, reflected in significantly mutated IG genes in the great majority (∼76%) of cases and predominance of the IGHV4-34 gene (22.8% of all cases). Immunogenetic comparisons revealed interesting similarities to SDRL, distinct from SMZL (Figure 5). In particular, most sequences in both entities were classified as significantly mutated, in contrast to SMZL (P = .004), where a large proportion of cases carry borderline/minimally mutated IGHV genes.42 A further significant distinction from SMZL concerned the usage of certain IGHV genes, in particular IGHV1-2*04.42 This gene, predominating by far in the SMZL repertoire (32%), was used much less frequently in either the present series (6.3%; P < .0001) or SDRL (5.8%).42 In contrast to the cytogenetic findings, there was no correlation between splenomegaly and immunogenetic data.

Comparison of immunogenetic features between CBL-MZ and primary splenic small B-cell lymphomas. (A) IGHV gene repertoire. The IGHV gene repertoire of CBL-MZ is significantly different from SMZL and resembles SDRL.42 (B) Somatic hypermutation. Most CBL-MZ cases carry a significant mutational load as evidenced by the germline identity of the clonotypic IG genes. Comparisons with SMZL and SDRL.42

Comparison of immunogenetic features between CBL-MZ and primary splenic small B-cell lymphomas. (A) IGHV gene repertoire. The IGHV gene repertoire of CBL-MZ is significantly different from SMZL and resembles SDRL.42 (B) Somatic hypermutation. Most CBL-MZ cases carry a significant mutational load as evidenced by the germline identity of the clonotypic IG genes. Comparisons with SMZL and SDRL.42

In summary, our cohort comprises cases with a clonal lymphocytosis, likely to have arisen from a MZ B cell. We have no evidence for an underlying causative agent or for a unique cytogenetic or immunogenetic profile. All cases present with BM involvement without splenomegaly, suggesting preferential homing and/or origin in the BM. However, expression of DBA.44 (normally associated with primary splenic lymphomas) in many cases and the subsequent splenic enlargement in some cases means that we cannot exclude a splenic origin. Currently, it is not possible to reliably distinguish the majority of cases of MZ-like clonal lymphocytosis that will remain clinically stable, despite prolonged follow up, from those destined to progress. Distinguishing among options 2, 3, and 4 therefore requires additional information. Recent next-generation sequencing studies have identified recurring genomic abnormalities in SMZL. It will be of interest to determine whether similar abnormalities are found within our cohort at presentation or are acquired during the course of their disease. These studies are in progress.

These data raise 2 questions of practical importance. First, mindful of increasing concerns about the implications of overdiagnosis, how should asymptomatic individuals found to have a lymphocytosis with MZ features be managed? Second, what name should be given to their condition?

The policy of all 3 centers contributing to this study has been to perform either computed tomography scanning or ultrasonography to exclude nodal and especially splenic enlargement. Based on our findings in this study, we would not recommend routine screening for extranodal lymphomas (eg, gastroscopy) in the absence of specific symptoms. Although BM examination is mandatory in patients presenting with or developing cytopenias and provided additional diagnostic information in our cohort, we recognize that many of our patients were elderly and frail and marrow examination would not alter their management. The observation that disease progression often can occur many years after presentation indicates the need for long-term follow-up.

Studies on CLL-like MBL suggest an increased incidence of bacterial infections even in the absence of progressive disease.43,44 Our cohort was too small to comment definitively, but we did not find an increased risk of significant infections despite the presence of mild hypogammaglobulinemia in some cases.

Regarding nomenclature, many cases could be classified as CD5 −ve MBL, but the cohort also included cases with weak CD5 positivity as seen in MZ lymphomas. It has been suggested that MBL could be more simply subclassified into CLL-like and non–Hodgkin-lymphoma-like categories, but our data would suggest that it is possible to define a distinct subgroup with MZ features. Our cohort also included cases with a clonal B-cell count exceeding 5 × 109/L. These cases did not differ in any other respect from cases with clonal B-cell counts of <5 × 109/L. As with the distinction between clinical MBL and early CLL, this finding raises questions about the clinical and biological validity of a numerical cutoff.

None of our cases are readily classifiable within the current WHO criteria. We suggest that a case could be made for a provisional entity that would encompass the cases we describe. It would be clinically important for the name not to imply a neoplastic, malignant, or lymphomatous process. Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis with marginal-zone features would be attractive but is constrained by the current diagnostic criteria for MBL. Clonal B-cell lymphocytosis with marginal-zone features is a possible alternative.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the ENosAI project (code 09SYN-13-880) cofunded by the European Union and the Hellenic General Secretariat for Research and Technology.

Authorship

Contribution: A.X., C.K., A.G., and P.B. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; T.P.V., M.K.A., S.S., A. Anagnostopoulos, and H.A.P. provided samples and associated clinical data and supervised research; G.K. and P.K. were responsible for histopathologic analysis; S.M., Z.D., E.S., N.M.-B., R.I., and A. Athanasiadou performed research; and T.P., K.S., G.A.P., and D.O. designed the study, supervised research, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kostas Stamatopoulos, Hematology Department and HCT Unit, G. Papanicolaou Hospital, 57010 Thessaloniki, Greece; e-mail: kostas.stamatopoulos@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

A.X., C.K., and A.G. contributed equally to this study.