Key Points

Humanized mice, IBMI-huNOG, were generated by intra–bone marrow injection of human CD133+ hematopoietic stem cells.

HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice recapitulated distinct ATL-like symptoms as well as HTLV-1–specific adaptive immune responses.

Abstract

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is causally associated with adult T-cell leukemia (ATL), an aggressive T-cell malignancy with a poor prognosis. To elucidate ATL pathogenesis in vivo, a variety of animal models have been established; however, the mechanisms driving this disorder remain poorly understood due to deficiencies in each of these animal models. Here, we report a novel HTLV-1–infected humanized mouse model generated by intra–bone marrow injection of human CD133+ stem cells into NOD/Shi-scid/IL-2Rγc null (NOG) mice (IBMI-huNOG mice). Upon infection, the number of CD4+ human T cells in the periphery increased rapidly, and atypical lymphocytes with lobulated nuclei resembling ATL-specific flower cells were observed 4 to 5 months after infection. Proliferation was seen in both CD25− and CD25+ CD4 T cells with identical proviral integration sites; however, a limited number of CD25+-infected T-cell clones eventually dominated, indicating an association between clonal selection of infected T cells and expression of CD25. Additionally, HTLV-1–specific adaptive immune responses were induced in infected mice and might be involved in the control of HTLV-1–infected cells. Thus, the HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mouse model successfully recapitulated the development of ATL and may serve as an important tool for investigating in vivo mechanisms of ATL leukemogenesis and evaluating anti-ATL drug and vaccine candidates.

Introduction

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is a retrovirus associated with adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) and HTLV-1–associated myelopathy or tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) in humans.1-3 Although the majority of HTLV-1–infected individuals remain asymptomatic throughout their lives, approximately 5% of HTLV-1 carriers develop ATL or HAM/TSP following a long latency period.4 In addition to the classic structural proteins required for retroviral replication, the HTLV-1 proviral genome encodes several accessory and regulatory proteins, including the viral transcriptional activator Tax and the HTLV-1 bZIP factor (HBZ), which are thought to be linked to HTLV-1 pathogenesis.5,6

ATL is an aggressive malignancy of mature CD4 T cells, characterized by frequent visceral involvement, lymphadenopathy, hypercalcemia or hypercytokinemia, and monoclonal proliferation of HTLV-1–infected tumor cells.7 Typical ATL cells exhibit an unusual morphology with lobulated nuclei, known as “flower cells.”8 These cells are also characterized by their robust expression of interleukin (IL)-2 receptor α (CD25).9

To reproduce the pathogenesis of ATL, a number of mouse models have been developed, including transgenic or xenografted/humanized mice.10-18 One such model is the Tax-transgenic mouse, which expresses Tax under the control of the Lck promoter. This model restricts Tax expression to developing thymocytes, resulting in characteristic ATL-like phenotypes.15 Another model, the HBZ-transgenic mouse, expresses HBZ under the control of a CD4-specific promoter/enhancer/silencer. These mice develop lymphomas characterized by induction of Foxp3 in CD4 T cells, similar to leukemic cells in ATL patients.18 These observations clearly demonstrate that the leukemogenic activity of not only Tax but also HBZ is related to the development of ATL.

In addition to transgenic mouse models, a variety of HTLV-1–infected small-animal models have been established to evaluate viral pathogenesis and elucidate the function of viral products in vivo.19,20 These infection models have provided valuable findings regarding virus-host interactions; however, they are unable to fully recapitulate pathological conditions resembling ATL, likely due to the low efficiency of HTLV-1 infection.

Humanized mice are highly susceptible to infection with human lymphotropic viruses such as EBV, HIV-1, and HTLV-1, and have been used to recapitulate specific disorders and human immune responses.17,21,22 Recent studies on HTLV-1 infection in humanized mouse models successfully reproduced HTLV-1–associated T-cell lymphomas16,17 ; however, these models did not accurately recreate human immune responses against HTLV-1. Notably, humoral immunity, along with cytotoxic T cell (CTL)-mediated cytotoxicity, is thought to play a pivotal role in controlling the proliferation or selection of HTLV-1–infected T-cell clones in vivo.23,24 It is therefore important to develop mouse models of ATL that induce more human-like HTLV-1–specific immune responses.

In this study, we describe a novel humanized mouse model of HTLV-1 infection in the presence of specific adaptive immune responses. Our novel HTLV-1–infected humanized mice displayed distinct ATL-like symptoms, including hepatosplenomegaly, hypercytokinemia, oligoclonal proliferation of HTLV-1–infected T cells, and the appearance of flower cells. In addition, HTLV-1–specific immunity was induced and may be involved in the control of infected cells in vivo.

Materials and methods

Purification of human CD133+ cells from cord blood

Cord blood samples from full-term human deliveries were obtained from the Japanese Red Cross Kinki Cord Blood Bank (Osaka, Japan) for research use due to the inadequate numbers of stem cells for human transplantation; all patients provided signed, informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were separated using Ficoll-Conray (Lymphosepar I, IBL) density gradient centrifugation. After collecting MNCs, a CD133 MicroBead Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) was used to isolate human CD133+ cells (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HLA-A typing was performed using a WAKFlow HLA typing kit (WAKUNAGA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions; the results are shown in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site).

NOG mice

Female 6-week-old NOD/Shi-scid/IL-2Rγc null (NOG) mice25 were purchased from the Central Institute of Experimental Animals (Kawasaki, Japan). Mice were handled under sterile conditions and were maintained in germ-free isolators. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committees of Kansai Medical University.

Generation of IBMI-huNOG

HTLV-1 infection to IBMI-huNOG

The HTLV-1–infected T-cell line MT228 was irradiated with 10 Gy from a 137Cs source irradiator. Irradiated MT2 cells (2.5 × 106) or phosphate-buffered saline were inoculated intraperitoneally into 24- to 28-week-old IBMI-huNOG mice. Mice were anesthetized and killed when the body weight decreased to <70% of their maximum weight. Peripheral blood smears were prepared using May-Grunwald Giemsa staining and examined by light microscopy. All infections were performed in a Biosafety Level P2A laboratory in accordance with the guidelines of Kansai Medical University.

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting

Peripheral blood cells were routinely collected every 2 weeks after infection, and after sacrificing mice, single-cell suspensions of various lymphoid tissues were prepared as described previously.29 To stain surface markers, anti–human CD45-PerCP or APC-Cy7, CD3–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7, CD4-PE, CD8-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD19-PE, CD25-FITC, CCR4-APC antibodies were used, along with mouse immunoglobllin G1 and FITC as an isotype control (all BD Biosciences). AccuCount Ultra Rainbow Fluorescent Particles (Spherotech) were employed to determine absolute cell numbers, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a BD FACSCan for 3-color staining and a BD FACSCant II (BD Biosciences) for 7-color staining. The CellQuest and Diva software programs were used for data acquisition (BD Biosciences), and the collected data were analyzed by FCS express 3 (De Novo Software). Human CD4-, CD8-, and CD25-expressing T cells were sorted from splenic MNCs by FACSAria or FACSAria III (BD Biosciences).

Tetramer staining

PE-conjugated HLA-A*24:02/Tax301-309 (SFHSLHLLF) and HLA-A*24:02/HIV (RYLRDQQLL) env gp160 tetramers were purchased from MBL. Splenocytes from mock-infected or HTLV-1–infected mice were stained with each tetramer and anti–human CD3 and CD8 antibodies according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Mixed lymphocyte-peptide cultures were performed to stimulate Tax-specific CTLs, as described previously.30 Briefly, splenocytes from HTLV-1–infected mice were cultured for 13 days with 10 mg/mL Tax301-309 peptide and 50 U/mL recombinant human IL-2 (Takeda Chemical Industries). Cultured splenocytes were then analyzed by flow cytometry.

DNA isolation and quantification of proviral load

Genomic DNA was extracted from single-cell suspensions of tissue or peripheral blood using a conventional phenol extraction method. Proviral loads (PVLs) were measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a MyiQ or CFX96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). The primers and probes targeting for HTLV-1 pX and human β-globin (HBB; as a internal control) are listed in supplemental Table 2. A plasmid containing PCR fragments for the HTLV-1 pX region and HBB was constructed using T-Vector pMD20 (TaKaRa) and used as the quantified standard template for real-time PCR.31 The PVL was calculated as: [(copy number of pX)/(copy number of HBB / 2)] × 100.

Quantification of clonal occupancy by clone-specific PCR

Inverse long PCR (IL-PCR) was performed to amplify the genomic DNA flanked the 3′ long terminal repeat of HTLV-1 provirus according to a modified method described previously.32 In brief, the genomic DNA was digested by PstI, self-ligated by T4 ligase, and then digested by MluI. Long PCR amplification of the linearized DNA was performed using the PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primer sets for IL-PCR analysis are listed in supplemental Table 3. IL-PCR products were isolated from agarose gels, purified, and subjected to nested PCR. Amplified nested PCR fragments were subcloned into T-Vector pMD20 (TaKaRa) and sequenced to obtain provirus integration sites downstream of the 3′ long terminal repeat. Integration site-specific primers were designed based on the DNA sequence of the flanking region of the provirus derived from splenic DNA of 8 HTLV-1–infected mice, and are listed in supplemental Table 5. A detailed description of the clone-specific quantitative PCR procedure has been provided elsewhere.33 The clonal occupancy of each clone was calculated as: [(copy number of integration sites)/(copy number of pX)] × 100.

Real-time RT-PCR to quantify tax and HBZ transcripts

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and complementary DNA samples were synthesized from 1 μg total RNA. Reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) was performed by the use of SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad). Primers used for RT-PCR are listed in supplemental Table 4. Relative expression levels were calculated by the MyiQ system (Bio-Rad).

Titration of HTLV-1–specific antibodies

The titers of antibodies against HTLV-1 antigens in the plasma of infected mice were determined by the particle agglutination method using Serodia HTLV-1 (Fuji Rebio).23 To deplete human immunoglobulin M (IgM) or immunoglobulin G (IgG), streptavidin M-PVA magnetic beads (Chemagen) preincubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti–human IgM or IgG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to plasma from infected mice; a goat anti–mouse IgG antibody (Organon Teknika) was used as the negative control.

Bio-Plex cytokine assay

Plasma levels of IL-1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-17, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), MCP-1, MIP-1β, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in HTLV-1–infected and control mice were analyzed using the Bio-Plex Human Cytokine 17-Plex Panel (Bio-Rad) on a Bio-Plex 200 system according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

The significance of differences was determined by Mann-Whitney U test, paired t test, or Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficient (r); P < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Reconstitution of human immune cells in NOG mice using IBMI

IBMI-huNOG mice were generated by IBMI of human CD133+ hematopoietic stem cells into sublethally irradiated 6- to 7-week-old NOG mice. After 1 month of transplantation, human CD45+ leukocytes were found to have almost completely reconstituted the bone marrow of recipient mice (Figure 1A). At this time point, the majority of the human leukocytes in bone marrow consisted of CD19+ cells. A substantial number of CD34+ cells were also detected, whereas human CD3+ cells had not developed.

Generation of IBMI-huNOG mice and T-cell development in periphery. (A) Development of human leukocytes in bone marrow of IBMI-huNOG mice. Bone marrow cells from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 20) at 1 mpt were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for expression of human CD45, CD19, and CD45, and mouse CD45 markers. Representatives (left) and the percentage of indicated markers (right) are shown. All cell populations were gated on mononuclear bone marrow cells. (B) Time course of human leukocyte development in the peripheral blood of IBMI-huNOG mice. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 40 for each time point) were stained for human CD45 at each time point. Box plots represent medians ± 1.5 IQR. (C) Increased number of human lymphocytes in IBMI-huNOG mice. Absolute numbers of human CD45+ and CD3+ cells in peripheral blood were determined by FACS analysis at each time point (n = 40 for each time point). (D) CD4-CD8 ratio in peripheral blood T cells. The CD4-CD8 ratio was calculated as follows: [(CD4 T-cell numbers per µL)/(CD8 T-cell numbers per µL)] (n = 40). (E) Sustained composition of human leukocytes in peripheral blood. PBMCs from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 8) were stained for human CD45, CD3, and CD19. Results are presented as mean percentages of human CD45+ cells.

Generation of IBMI-huNOG mice and T-cell development in periphery. (A) Development of human leukocytes in bone marrow of IBMI-huNOG mice. Bone marrow cells from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 20) at 1 mpt were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for expression of human CD45, CD19, and CD45, and mouse CD45 markers. Representatives (left) and the percentage of indicated markers (right) are shown. All cell populations were gated on mononuclear bone marrow cells. (B) Time course of human leukocyte development in the peripheral blood of IBMI-huNOG mice. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 40 for each time point) were stained for human CD45 at each time point. Box plots represent medians ± 1.5 IQR. (C) Increased number of human lymphocytes in IBMI-huNOG mice. Absolute numbers of human CD45+ and CD3+ cells in peripheral blood were determined by FACS analysis at each time point (n = 40 for each time point). (D) CD4-CD8 ratio in peripheral blood T cells. The CD4-CD8 ratio was calculated as follows: [(CD4 T-cell numbers per µL)/(CD8 T-cell numbers per µL)] (n = 40). (E) Sustained composition of human leukocytes in peripheral blood. PBMCs from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 8) were stained for human CD45, CD3, and CD19. Results are presented as mean percentages of human CD45+ cells.

Less than half of peripheral blood cells were composed of human leukocytes even at 2 months posttransplantation (mpt). However, the number of human leukocytes increased in a time-dependent manner (Figure 1B-C). Between 3 and 4 mpt, the number of human CD3+ T cells in the peripheral blood increased dramatically, as did the CD4-CD8 ratio (Figure 1D). CD3+ T cells and the CD4-CD8 ratio reached stable levels by 4 to 5 mpt, suggesting that the development of human T cells was completed within this period.

Previous reports have shown that reconstituted human CD45+ cells in other types of humanized mouse systems were overcome by CD3+ T cells within several months of transplantation due to the reduction of B-cell development,21,34 which may impair the integrity of host immunity. In contrast, the IBMI-huNOG mice model maintained a stable number of CD3+ T cells as well as the B- to T-cell ratio in peripheral blood through at least 8 mpt (Figure 1E). Thus, the human immune system appeared to be effectively reconstituted in IBMI-huNOG mice, likely due to the enriched repopulation of long-term hematopoietic stem cells by direct injection of CD133+ cells into the bone marrow cavity.27

Proliferation of HTLV-1–infected T cells in IBMI-huNOG mice

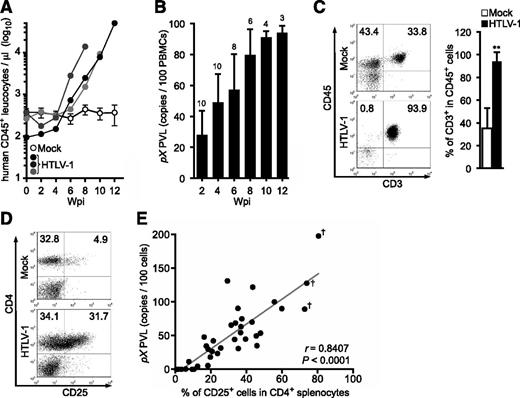

Human T lymphocytes fully developed in IBMI-huNOG mice within 4 to 5 mpt. These mice were then infected with HTLV-1 by intraperitoneal inoculation with 2.5 × 106 irradiated MT2 cells. The number of human CD45+ leukocytes began to increase as early as 4 to 6 weeks postinoculation (wpi) and continued to increase rapidly thereafter (Figure 2A). HTLV-1 infection was also detected by 2 wpi, with the HTLV-1 PVL in peripheral blood increasing in a time-dependent manner (Figure 2B). The proportion of CD3+/CD45+ T lymphocytes was significantly enriched in HTLV-1–infected mice relative to mock-infected controls (Figure 2C), consistent with previous results.16 Absence of residual MT2 cells used as the source of HTLV-1 was confirmed by MT2 cell-specific PCR as previously described (supplemental Figure 1).35

Kinetic analysis of HTLV-1 provirus in infected IBMI-huNOG mice. (A) Quantification of leukocyte numbers in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected mice. Peripheral blood was routinely collected from mock- and HTLV-1–infected mice every 2 weeks. Human CD45+ leukocytes were enumerated by FACS. Results from mock-infected mice (n = 10) are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and representative results of 3 HTLV-1–infected mice are shown. (B) Quantification of HTLV-1 PVL in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected mice. The PVL was determined by real-time PCR. Number at the top of each bar represents the number of analyzed HTLV-1–infected mice at each time point. (C) Expansion of CD3+ T-cell populations in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected mice. PBMCs from mock-infected (n = 3) and HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 18) were stained for human CD3 when sacrificed; the median value was 8 wpi. Results are presented as the average percentages ± SD of human CD45+ cells. (D) Expansion of CD25+ CD4 T cells in the spleen of HTLV-1–infected mice. Splenocytes were stained for human CD3, CD4, and CD25 and analyzed by FACS. Representative results from mock-infected (mouse ID: 8X20) and HTLV-1–infected (mouse ID: 8X01) mice are shown. (E) Correlation between the percentages of CD25+ T cells and PVLs in the spleen. HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 37) were sacrificed to determine PVL and CD25+ T-cell frequency in CD4+ splenocytes. One dot represents the result of an individual HTLV-1–infected mouse. Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficient (r) was adopted to identify statistically significant correlations between values. Daggers indicate that flower cells were observed in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected mice.

Kinetic analysis of HTLV-1 provirus in infected IBMI-huNOG mice. (A) Quantification of leukocyte numbers in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected mice. Peripheral blood was routinely collected from mock- and HTLV-1–infected mice every 2 weeks. Human CD45+ leukocytes were enumerated by FACS. Results from mock-infected mice (n = 10) are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and representative results of 3 HTLV-1–infected mice are shown. (B) Quantification of HTLV-1 PVL in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected mice. The PVL was determined by real-time PCR. Number at the top of each bar represents the number of analyzed HTLV-1–infected mice at each time point. (C) Expansion of CD3+ T-cell populations in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected mice. PBMCs from mock-infected (n = 3) and HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 18) were stained for human CD3 when sacrificed; the median value was 8 wpi. Results are presented as the average percentages ± SD of human CD45+ cells. (D) Expansion of CD25+ CD4 T cells in the spleen of HTLV-1–infected mice. Splenocytes were stained for human CD3, CD4, and CD25 and analyzed by FACS. Representative results from mock-infected (mouse ID: 8X20) and HTLV-1–infected (mouse ID: 8X01) mice are shown. (E) Correlation between the percentages of CD25+ T cells and PVLs in the spleen. HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 37) were sacrificed to determine PVL and CD25+ T-cell frequency in CD4+ splenocytes. One dot represents the result of an individual HTLV-1–infected mouse. Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficient (r) was adopted to identify statistically significant correlations between values. Daggers indicate that flower cells were observed in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected mice.

HTLV-1–infected humanized mice showed marked expansion of CD25+ CD4 T cells in the spleen relative to mock-infected controls (Figure 2D; Table 1), as is observed in peripheral blood of ATL and HAM/TSP patients.9,36 Furthermore, PVLs in the spleen were significantly correlated with the rate of CD25+ CD4 T cells (Figure 2E). These data suggest that the expanded CD25+ CD4 T-cell population represents the majority of HTLV-1–infected cells in vivo.

Pathological features of mock- or HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice

| Mouse ID* . | Wpi† . | PVL‡ . | CD3+CD4+ (%)§ . | CD4+CD25+ (%)§ . | Spleen weight (mg) . | Lymph node weight (mg)|| . | Observations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8807 | — | — | 16.7 | 2.6 | 45 | 1 | Mock infected |

| 8X10 | — | — | 20.2 | 3.4 | 51 | 3 | Mock infected |

| 8X20 | — | — | 36.5 | 4.4 | 40 | 2 | Mock infected |

| 8401 | 17 | 65.6 | 53.1 | 31.4 | 195 | 23 | |

| 8402 | 11 | 0.1 | 5.3 | 0.7 | 26 | 1 | |

| 8403 | 14 | 0.1 | 10.8 | 3.4 | 35 | 1 | |

| 8404 | 17 | 5.4 | 53.4 | 18.3 | 68 | 2 | |

| 8405 | 12 | 11.3 | 30.3 | 7.6 | 59 | 14 | |

| 8406 | 5 | 0.1 | 10.5 | 1.5 | 33 | 3 | |

| 8407 | 8 | 4.5 | 69.6 | 12.5 | 166 | 9 | |

| 8801 | 25 | 0.1 | 59.6 | 10.4 | 187 | 7 | |

| 8803 | 30 | 0.4 | 38.6 | 5.8 | 55 | 11 | |

| 8804 | 23 | 0.1 | 46.6 | 9.5 | 105 | 5 | |

| 8805 | 8 | 70.0 | 57.0 | 43.1 | 233 | 37 | Leukemia |

| 8808 | 8 | 26.5 | 52.5 | 20.6 | 101 | 40 | |

| 8810 | 4 | 42.2 | 55.4 | 21.3 | 40 | 22 | |

| 8X01 | 5 | 44.9 | 65.8 | 39.5 | 208 | 11 | |

| 8X04 | 8 | 121.9 | 62.2 | 43.5 | 165 | 7 | Leukemia |

| 8X05 | 23 | 127.7 | 81.4 | 73.9 | 226 | 8 | Leukemia, flower cells (10.6%),¶ tumor lesion |

| 8X06 | 9 | 31.6 | 50.5 | 25.5 | 155 | 5 | |

| 8X09 | 5 | 34.6 | 52.2 | 17.4 | 227 | 9 | |

| 8X12 | 4 | 47.9 | 58.5 | 16.2 | 188 | 11 | |

| 8X14 | 25 | 68.6 | 51.4 | 33.8 | 145 | 25 | Leukemia |

| 8X16 | 7 | 90.4 | 78.9 | 35.2 | 200 | 16 | Leukemia |

| 8X17# | 9 | 131.1 | 44.6 | 29.3 | 200 | 35 | Leukemia |

| 8X18 | 18 | 197.7 | 89.4 | 80.5 | 358 | 28 | Leukemia, flower cells (19.2%),¶ tumor lesion |

| 9Z01 | 10 | 53.6 | 75.8 | 47.9 | 220 | 12 | Leukemia |

| 9Z03 | 6 | 23.4 | 51.6 | 23.7 | 38 | 18 | |

| 9Z17 | 6 | 18.2 | 64.7 | 19.7 | 163 | 10 | |

| 9Z18 | 16 | 89.2 | 80.4 | 72.7 | 285 | 5 | Leukemia, flower cells (4.2%),¶ tumor lesion |

| 9Z19 | 6 | 35.0 | 65.0 | 45.9 | 207 | 20 | |

| X202 | 12 | 90.0 | 76.6 | 59.9 | 353 | 13 | Leukemia |

| X206 | 8 | 54.4 | 56.6 | 36.7 | 317 | 15 | |

| X207** | 11 | 100.0 | 62.2 | 55.7 | 358 | 6 | Leukemia |

| X208 | 4 | 29.9 | 74.7 | 18.4 | 188 | 15 | |

| X209 | 7 | 30.8 | 74.4 | 35.4 | 270 | 21 | |

| X212 | 9 | 74.9 | 56.8 | 37.4 | 270 | 5 | Leukemia |

| X214 | 10 | 44.3 | 48.0 | 33.3 | 170 | 6 | |

| X216 | 8 | 63.2 | 66.1 | 36.9 | 271 | 12 | Leukemia |

| X217 | 7 | 49.6 | 76.9 | 45.5 | 306 | 18 | Leukemia |

| Mouse ID* . | Wpi† . | PVL‡ . | CD3+CD4+ (%)§ . | CD4+CD25+ (%)§ . | Spleen weight (mg) . | Lymph node weight (mg)|| . | Observations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8807 | — | — | 16.7 | 2.6 | 45 | 1 | Mock infected |

| 8X10 | — | — | 20.2 | 3.4 | 51 | 3 | Mock infected |

| 8X20 | — | — | 36.5 | 4.4 | 40 | 2 | Mock infected |

| 8401 | 17 | 65.6 | 53.1 | 31.4 | 195 | 23 | |

| 8402 | 11 | 0.1 | 5.3 | 0.7 | 26 | 1 | |

| 8403 | 14 | 0.1 | 10.8 | 3.4 | 35 | 1 | |

| 8404 | 17 | 5.4 | 53.4 | 18.3 | 68 | 2 | |

| 8405 | 12 | 11.3 | 30.3 | 7.6 | 59 | 14 | |

| 8406 | 5 | 0.1 | 10.5 | 1.5 | 33 | 3 | |

| 8407 | 8 | 4.5 | 69.6 | 12.5 | 166 | 9 | |

| 8801 | 25 | 0.1 | 59.6 | 10.4 | 187 | 7 | |

| 8803 | 30 | 0.4 | 38.6 | 5.8 | 55 | 11 | |

| 8804 | 23 | 0.1 | 46.6 | 9.5 | 105 | 5 | |

| 8805 | 8 | 70.0 | 57.0 | 43.1 | 233 | 37 | Leukemia |

| 8808 | 8 | 26.5 | 52.5 | 20.6 | 101 | 40 | |

| 8810 | 4 | 42.2 | 55.4 | 21.3 | 40 | 22 | |

| 8X01 | 5 | 44.9 | 65.8 | 39.5 | 208 | 11 | |

| 8X04 | 8 | 121.9 | 62.2 | 43.5 | 165 | 7 | Leukemia |

| 8X05 | 23 | 127.7 | 81.4 | 73.9 | 226 | 8 | Leukemia, flower cells (10.6%),¶ tumor lesion |

| 8X06 | 9 | 31.6 | 50.5 | 25.5 | 155 | 5 | |

| 8X09 | 5 | 34.6 | 52.2 | 17.4 | 227 | 9 | |

| 8X12 | 4 | 47.9 | 58.5 | 16.2 | 188 | 11 | |

| 8X14 | 25 | 68.6 | 51.4 | 33.8 | 145 | 25 | Leukemia |

| 8X16 | 7 | 90.4 | 78.9 | 35.2 | 200 | 16 | Leukemia |

| 8X17# | 9 | 131.1 | 44.6 | 29.3 | 200 | 35 | Leukemia |

| 8X18 | 18 | 197.7 | 89.4 | 80.5 | 358 | 28 | Leukemia, flower cells (19.2%),¶ tumor lesion |

| 9Z01 | 10 | 53.6 | 75.8 | 47.9 | 220 | 12 | Leukemia |

| 9Z03 | 6 | 23.4 | 51.6 | 23.7 | 38 | 18 | |

| 9Z17 | 6 | 18.2 | 64.7 | 19.7 | 163 | 10 | |

| 9Z18 | 16 | 89.2 | 80.4 | 72.7 | 285 | 5 | Leukemia, flower cells (4.2%),¶ tumor lesion |

| 9Z19 | 6 | 35.0 | 65.0 | 45.9 | 207 | 20 | |

| X202 | 12 | 90.0 | 76.6 | 59.9 | 353 | 13 | Leukemia |

| X206 | 8 | 54.4 | 56.6 | 36.7 | 317 | 15 | |

| X207** | 11 | 100.0 | 62.2 | 55.7 | 358 | 6 | Leukemia |

| X208 | 4 | 29.9 | 74.7 | 18.4 | 188 | 15 | |

| X209 | 7 | 30.8 | 74.4 | 35.4 | 270 | 21 | |

| X212 | 9 | 74.9 | 56.8 | 37.4 | 270 | 5 | Leukemia |

| X214 | 10 | 44.3 | 48.0 | 33.3 | 170 | 6 | |

| X216 | 8 | 63.2 | 66.1 | 36.9 | 271 | 12 | Leukemia |

| X217 | 7 | 49.6 | 76.9 | 45.5 | 306 | 18 | Leukemia |

Leukemia, infected mice with atypical lymphocytes >90% of PBMCs; flower cells, atypical lymphocytes with >4 lobulated nuclei in a cell; tumor lesion, tumor formation of infiltrating infected T cells in the liver.

The 37 infected mice listed are identical to those in Figure 2E.

The wpi when indicated mice were sacrificed.

PVL is expressed as number of pX copies per 100 cells.

The population of indicated marker-positive cells in CD45+ splenocytes.

The weight value of one of the largest mesenteric lymph node in each mouse.

The percentage of flower cells in total lymphocytes in blood smear (presented in parentheses).

High proportion of CD25+ CD8 T cells in PBMCs.

High proportion of DP T cells in PBMCs.

ATL-like leukemic symptoms in HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice

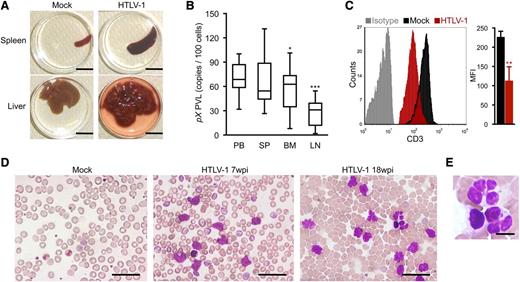

The majority of HTLV-1–infected mice exhibited splenomegaly, while apparent infiltration of infected T cells in the liver was observed in 3 infected mice with flower cells (Figure 3A; Table 1) and the weight of liver in these mice was remarkably increased (HTLV-1: 1550 ± 620 mg [n = 3]; mock: 715 ± 85 mg [n = 3]). When PVLs of several lymphoid organs were analyzed, the proportions of infected cells in the bone marrow and lymph nodes were significantly lower than those in the spleen and peripheral blood, consistent with the leukemic phenotype of infected mice (Figure 3B). This result is in striking contrast to other humanized mouse models, in which HTLV-1 infection17 or the ectopic expression of Tax16 preferentially induce lymphoma.

Splenomegaly and leukemic T-cell overgrowth in infected IBMI-huNOG mice. (A) Hepatosplenomegaly in HTLV-1–infected mice. Representative spleens and livers from mock- and HTLV-1–infected mice are shown. Scale bars in panel A represent 10 mm. (B) PVL in lymphoid organs of HTLV-1–infected mice. PVL in the peripheral blood (PB), spleen (SP), bone marrow (BM), and lymph nodes (LM) of HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 17) are shown. Box plots represent medians ± 1.5 IQR. Asterisks indicate statistical significance vs the value obtained from peripheral blood (*P < .05, ***P < .001 by paired t test). (C) Downregulation of CD3 on the T-cell surface. PBMCs from mock- (n = 3) and HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 18) were stained for human CD3 and analyzed by FACS. Results are presented as mean MFI ± SD of CD3 expression. (D-E) Smears of peripheral blood from HTLV-1–infected mice showing a number of leukemic cells with atypically shaped nuclei. Results from two infected mice (7 and 18 wpi, respectively) and a mock-infected mouse (at 8 mpt) are shown. Higher-magnification view of flower cells in panel D is shown in panel E. Scale bars in panels D-E represent 50 and 10 µm, respectively. Asterisks in panels B and C represent significant differences vs mock-infected mice (**P < .01 by Mann-Whitney U test).

Splenomegaly and leukemic T-cell overgrowth in infected IBMI-huNOG mice. (A) Hepatosplenomegaly in HTLV-1–infected mice. Representative spleens and livers from mock- and HTLV-1–infected mice are shown. Scale bars in panel A represent 10 mm. (B) PVL in lymphoid organs of HTLV-1–infected mice. PVL in the peripheral blood (PB), spleen (SP), bone marrow (BM), and lymph nodes (LM) of HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 17) are shown. Box plots represent medians ± 1.5 IQR. Asterisks indicate statistical significance vs the value obtained from peripheral blood (*P < .05, ***P < .001 by paired t test). (C) Downregulation of CD3 on the T-cell surface. PBMCs from mock- (n = 3) and HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 18) were stained for human CD3 and analyzed by FACS. Results are presented as mean MFI ± SD of CD3 expression. (D-E) Smears of peripheral blood from HTLV-1–infected mice showing a number of leukemic cells with atypically shaped nuclei. Results from two infected mice (7 and 18 wpi, respectively) and a mock-infected mouse (at 8 mpt) are shown. Higher-magnification view of flower cells in panel D is shown in panel E. Scale bars in panels D-E represent 50 and 10 µm, respectively. Asterisks in panels B and C represent significant differences vs mock-infected mice (**P < .01 by Mann-Whitney U test).

May-Grunwald Giemsa staining of peripheral blood smears from infected mice revealed the presence of large, abnormal leukemic cells with lobulated nuclei, which were morphologically identical to the flower cells observed in ATL patients (Figure 3D-E).8 The activated phenotype of infected T cells was also evident, with clear downregulation of CD3 expression on the surface of peripheral T cells in HTLV-1–infected mice, similar to that seen in ATL cells (Figure 3C).37

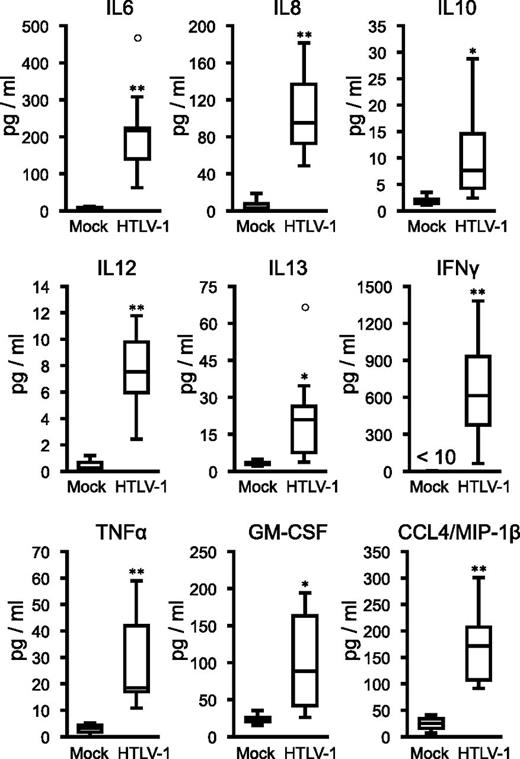

ATL cells have been shown to secrete proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α, and GM-CSF, which stimulate activation and proliferation of infected T cells and promote development of ATL leukemogenesis.38-40 Analysis of cytokine and chemokine levels in the plasma of HTLV-1–infected mice revealed significantly elevated levels of several proinflammatory cytokines (Figure 4). The concentration of IFNγ significantly correlated with PVL in the peripheral blood (supplemental Figure 2), suggesting Th1 immune responses induced in infected mice. Together, these results suggest that HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice accurately recreate many of the pathological features of ATL, including hepatosplenomegaly, leukemic T-cell overgrowth with lobulated nuclei, hypercytokinemia, and downregulation of CD3 on T cells.

Induction of inflammatory cytokines in infected IBMI-huNOG mice. Human cytokine concentrations in plasma. Plasma was collected following sacrifice of mock-infected (n = 4) and HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 8). Seventeen cytokines were quantified using a cytokine bead array system. The concentrations of human IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IFNγ, TNF-α, GM-CSF, and CCL4/MIP-1β are shown, all of which were significantly increased in the plasma of HTLV-1–infected mice. Increased expressions of the other 6 cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-17, G-CSF, and MCP-1) were also observed in infected mice but not statistically significant. On the other hand, little decrease in the concentrations of IL-1 and IL-5 was seen. Asterisks in each panel represent significant differences vs mock-infected mice (*P < .05, **P < .01 by Mann-Whitney U test).

Induction of inflammatory cytokines in infected IBMI-huNOG mice. Human cytokine concentrations in plasma. Plasma was collected following sacrifice of mock-infected (n = 4) and HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 8). Seventeen cytokines were quantified using a cytokine bead array system. The concentrations of human IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IFNγ, TNF-α, GM-CSF, and CCL4/MIP-1β are shown, all of which were significantly increased in the plasma of HTLV-1–infected mice. Increased expressions of the other 6 cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-17, G-CSF, and MCP-1) were also observed in infected mice but not statistically significant. On the other hand, little decrease in the concentrations of IL-1 and IL-5 was seen. Asterisks in each panel represent significant differences vs mock-infected mice (*P < .05, **P < .01 by Mann-Whitney U test).

Oligoclonal proliferation of human T-cell clones in HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice

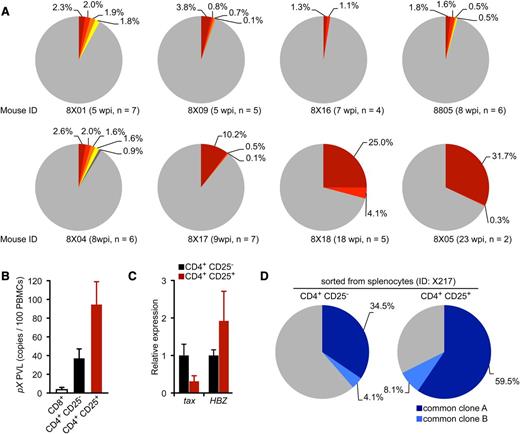

To evaluate the clonal proliferation of HTLV-1–infected T cells in infected mice, we quantified cellular clonality using clone-specific real-time PCR analysis. Splenocytes were isolated from 8 infected mice sacrificed at various time points, and genomic DNA fragments flanking the major integration sites in the HTLV-1–infected cells were amplified by IL-PCR. Amplified DNA fragments were subcloned into plasmids and sequenced to confirm proper integration (supplemental Table 5). As shown in Figure 5A, the occupancy of detected clones determined by real-time PCR was < 5% in cells harvested 5 to 8 wpi, indicating polyclonal HTLV-1 infection in these mice. In contrast, 2 mice sacrificed after prolonged infection periods (18 and 23 wpi, respectively) produced high percentages of infected clones. Interestingly, these 2 mice also showed overgrowth of CD25+ CD4 T cells with flower-shaped nuclei, characteristic of ATL cells (Figure 3D-E), whereas such cells were not observed in the 6 remaining mice. These findings indicate that a limited number of HTLV-1–infected T-cell clones selectively proliferated in the spleens of infected mice, resulting in an ATL-like leukemic phenotype.33,41

Progression of clonality in splenocytes of infected IBMI-huNOG. (A) Occupancy of HTLV-1–infected clones in the spleen. Abundant integration sites of HTLV-1 provirus were amplified by IL-PCR and subcloned into plasmids. The number of integration sites in each splenic DNA sample was determined by quantitative PCR using the clone-specific nucleotide sequence for each integration site. Results from 8 individual HTLV-1–infected mice are shown as pie charts. Size of the slice is proportional to the relative abundance of T-cell clones successfully amplified by IL-PCR, while data of minor clones with less than 0.1% occupancy were omitted. Gray regions represent clones with undefined integration sites. n, number of integration sites determined by nucleotide sequence of cloned PCR fragments in each mouse. (B) PVLs of specifiedT-cell populations. Splenocytes from HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 5) were sorted into CD25− or CD25+ CD4 T cells and CD8+ T cells. Genomic DNA isolated from each T-cell population was analyzed for PVL by real-time PCR using primers for the pX region of HTLV-1. (C) Comparative analysis of viral transcripts in CD25− and CD25+ CD4 T-cell populations. Splenocytes from HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 5) are identical to those in mentioned above. The expression levels of tax (left) and HBZ (right) were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR and were normalized to that of HPRT1. Results are presented as the fold change compared with the value in CD25− CD4 T cells. (D) Detection of common T-cell clones in the CD25− and CD25+ CD4 T-cell populations. Clonal occupancy in both CD25− and CD25+ populations are presented as pie charts. Two abundant common clones were analyzed for occupancy. Identified integration sites are listed in supplemental Table 5. The purity of each sorted population was >95% (supplemental Figure 3).

Progression of clonality in splenocytes of infected IBMI-huNOG. (A) Occupancy of HTLV-1–infected clones in the spleen. Abundant integration sites of HTLV-1 provirus were amplified by IL-PCR and subcloned into plasmids. The number of integration sites in each splenic DNA sample was determined by quantitative PCR using the clone-specific nucleotide sequence for each integration site. Results from 8 individual HTLV-1–infected mice are shown as pie charts. Size of the slice is proportional to the relative abundance of T-cell clones successfully amplified by IL-PCR, while data of minor clones with less than 0.1% occupancy were omitted. Gray regions represent clones with undefined integration sites. n, number of integration sites determined by nucleotide sequence of cloned PCR fragments in each mouse. (B) PVLs of specifiedT-cell populations. Splenocytes from HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 5) were sorted into CD25− or CD25+ CD4 T cells and CD8+ T cells. Genomic DNA isolated from each T-cell population was analyzed for PVL by real-time PCR using primers for the pX region of HTLV-1. (C) Comparative analysis of viral transcripts in CD25− and CD25+ CD4 T-cell populations. Splenocytes from HTLV-1–infected mice (n = 5) are identical to those in mentioned above. The expression levels of tax (left) and HBZ (right) were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR and were normalized to that of HPRT1. Results are presented as the fold change compared with the value in CD25− CD4 T cells. (D) Detection of common T-cell clones in the CD25− and CD25+ CD4 T-cell populations. Clonal occupancy in both CD25− and CD25+ populations are presented as pie charts. Two abundant common clones were analyzed for occupancy. Identified integration sites are listed in supplemental Table 5. The purity of each sorted population was >95% (supplemental Figure 3).

Presence of identical infected clones in CD25− and CD25+ CD4 T-cell populations

Splenocytes from infected mice were sorted into CD25− or CD25+ CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells; the PVL of each population was also determined. Most of the CD25+ CD4 T cells isolated from the spleens of infected mice were provirus-positive, as was a significant proportion of CD25− CD4 T cells, whereas infection of CD8 T cells was rare (Figure 5B). Interestingly, tax expression in HTLV-1–infected CD25+ CD4 T cells was suppressed compared with that in CD25− CD4 T cells; however, higher HBZ expression was observed in CD25+ CD4 T cells (Figure 5C).

Further clonality analysis for HTLV-1–infected CD25− and CD25+ CD4 T cells isolated from the same spleen with the purity of >95% (supplemental Figure 3) revealed that the most abundant clone was the same in both T-cell populations; however, the occupancy was higher in the CD25+ population (Figure 5D), indicating the preferential growth of infected clones with CD25 expression.

Induction of HTLV-1–specific adaptive immune responses in HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice

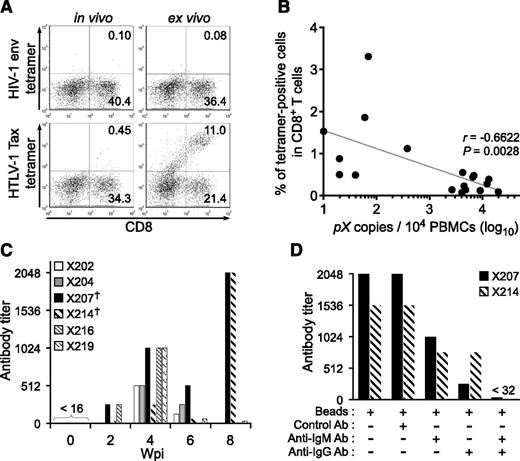

HLA-A*24:02–restricted Tax-specific CTLs were frequently detected in ATL patients, and are known to play an important role in the control of HTLV-1–infected cells in vivo.42-44 To investigate whether Tax-specific CTLs were induced in HTLV-1–infected mice, the IBMI-huNOG mice were generated using hematopoietic stem cells purified from the cord blood of an HLA-A*24:02 haplotype individual. HLA-A*24:02 tetramers coupled with Tax301-309 were used to detect CTLs. The cord blood HLA-A alleles used in this study are shown in supplemental Table 1. As shown in Figure 6A, Tax301-309–specific CTLs were detected in HTLV-1–infected mice at a frequency similar to that of ATL patients (0.7% ± 0.8%, n = 18),45 whereas control tetramer CTLs specific for HIV env produced only marginal staining of CD8 T cells.

Induction of cellular and humoral immune responses against HTLV-1 in infected IBMI-huNOG mice. (A) Detection of HTLV-1–specific HLA-A*24:02-restricted CTLs. Splenocytes from HTLV-1–infected mice at 8 wpi were stained with human CD8 and Tax301-309 tetramer or HIV-1 env gp160 tetramer as a negative control, respectively. Representative results of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells in vivo (left) and ex vivo culture with Tax peptide (right) are shown. (B) Inverse correlation between PVL and the frequency of Tax301-309–specific CTLs. The percentages of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells and PVL in the spleens of 18 HTLV-1–infected mice are shown. One dot represents the result of an individual HTLV-1–infected mouse. Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficient (r2) was used to identify statistically significant correlations. (C) HTLV-1–specific antibody responses in HTLV-1–infected mice. HTLV-1–specific antibody titers in plasma were monitored by the particle agglutination method. Each bar represents an individual mouse. The plasma of indicated mice prior to infection were used as negative-controls (shown as 0 wpi), and these titers were undetectable level (<16). Mice with daggers (mouse ID: X207 and X214) showed biphasic induction of antibody responses; titers peaked at 8 wpi. (D) Detection of HTLV-1–specific IgM or IgG antibody. Antibody depletion was performed by addition of goat antibodies against human IgG or IgM and anti-goat antibody conjugated magnetic beads to the plasma of two mice, as shown in panel C (indicated by daggers). Bars represent antibody titers in the individual X207 and X214 mice. Ab, antibody.

Induction of cellular and humoral immune responses against HTLV-1 in infected IBMI-huNOG mice. (A) Detection of HTLV-1–specific HLA-A*24:02-restricted CTLs. Splenocytes from HTLV-1–infected mice at 8 wpi were stained with human CD8 and Tax301-309 tetramer or HIV-1 env gp160 tetramer as a negative control, respectively. Representative results of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells in vivo (left) and ex vivo culture with Tax peptide (right) are shown. (B) Inverse correlation between PVL and the frequency of Tax301-309–specific CTLs. The percentages of tetramer-positive CD8 T cells and PVL in the spleens of 18 HTLV-1–infected mice are shown. One dot represents the result of an individual HTLV-1–infected mouse. Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficient (r2) was used to identify statistically significant correlations. (C) HTLV-1–specific antibody responses in HTLV-1–infected mice. HTLV-1–specific antibody titers in plasma were monitored by the particle agglutination method. Each bar represents an individual mouse. The plasma of indicated mice prior to infection were used as negative-controls (shown as 0 wpi), and these titers were undetectable level (<16). Mice with daggers (mouse ID: X207 and X214) showed biphasic induction of antibody responses; titers peaked at 8 wpi. (D) Detection of HTLV-1–specific IgM or IgG antibody. Antibody depletion was performed by addition of goat antibodies against human IgG or IgM and anti-goat antibody conjugated magnetic beads to the plasma of two mice, as shown in panel C (indicated by daggers). Bars represent antibody titers in the individual X207 and X214 mice. Ab, antibody.

To evaluate whether functionally reactive Tax301-309–specific CTLs were present in infected mice, we cultured splenocytes from HTLV-1–infected mice in the presence of Tax peptide. Tax301-309 specific CTLs clearly proliferated following peptide stimulation; no reaction was seen in controls. Furthermore, the frequency of Tax301-309–specific CTLs in in vivo CD8 T cells was inversely correlated with the PVLs of HTLV-1–infected mice (Figure 6B). These results suggest that HTLV-1–infected mice induce functional T-cell–mediated cellular immunity against HTLV-1, which may be involved in the control of HTLV-1–infected cells in vivo.

Antibodies against HTLV-1 antigens were also detected in the plasma of infected mice as early as 2 wpi, whereas the specific antibody was not detected before infection (Figure 6C). The titer of HTLV-1–specific antibodies increased in all cases until 4 wpi, followed by a gradual decline in 67% of infected mice (4 of 6), coincident with a decrease in body weight. However, 2 of the infected mice exhibited a reactivation of antibody production at 8 wpi, suggestive of immunoglobulin class switching from IgM to IgG. In fact, HTLV-1–specific antibody titers were significantly decreased following selective depletion of human IgG, indicating the presence of functional IgG in the plasma of HTLV-1–infected mice (Figure 6D). These data clearly support the notion that the functional interaction between human T and B cells required for class switching exists in this model. Taken together, these results demonstrate that human-like adaptive immunity against HTLV-1 was established in the HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice.

Discussion

In this study, we established a novel humanized mouse model of HTLV-1 infection. To generate humanized mice, we transplanted human stem cells directly into the bone marrow cavity of NOD/Shi-SCID/IL-2Rγc null (NOG) mice using an IBMI method.

The efficacy of humanization achieved in this model is markedly superior to other procedures, such as intrahepatic or intravenous injection of human hematopoietic stem cells.21,22,29 While T-lineage–cell populations become dominant over B-cell populations in the lymphoid organs of other humanized mouse systems within a few months after transplantation, in IBMI-huNOG mice the B-to-T-cell ratio remained constant for >8 months posttransplantation (Figure 1E). One possible explanation for this difference is that direct injection of hematopoietic stem cell preparations into the bone marrow of recipient mice improves the colonization efficiency of long-term stem cells.27,46 Moreover, we used CD133+ cells to generate IBMI-huNOG mice. CD133, the early hematopoietic progenitor cell marker, is thought to be ancestral to CD34 in human hematopoiesis.47 Previous studies have revealed that CD133+ cells were capable of differentiating not only into hematopoietic cells but also into endothelial, stromal, neuronal, and other type of cells.47-49 It is possible that human mesenchymal stromal cells derived from CD133+ cells support the development and maintenance of human B cells in the bone marrow microenvironment.

Having established a new humanized mouse model, we then infected IBMI-huNOG mice with HTLV-1 through inoculation with sublethally irradiated HTLV-1–producing cells.28 HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice recapitulated a large number of pathological features characteristic of ATL patients, including hyperproliferation of CD3+ T cells, clonal proliferation of CD25+ CD4 T cells, the appearance of flower cells in the periphery, hepatosplenomegaly, inflammatory hypercytokinemia, and downregulation of CD3 on T cells.

Overgrowth of infected T cells was correlated with the expression of CD25 on CD4 T cells, consistent with recent reports.17 However, the substantial proportion of CD25− CD4 T cells were also infected and identical T-cell clones, as determined by provirus integration site, were detected as the most abundant clones in both CD25− and CD25+ CD4 T-cell populations, suggesting that CD25 expression likely occurs after infection in the course of clonal expansion. In addition, the expressions of tax and CD25 were inversely correlated. Further research will be necessary to identify molecular events associated with the suppression of tax expression in HTLV-1–infected CD25+ CD4 T cells in relation to the development of ATL.

Banerjee et al16 described the development of T-cell lymphoma following bone marrow transplantation of HTLV-1–infected CD34+/CD38− hematopoietic stem cells into a NOD/SCID mouse. The lymphoma cells in these mice were capable of infiltrating into multiple organs but represented only CD25− or CD25low phenotypes. In contrast, HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice developed leukemia in CD25+ CD4 T cells, similar to that observed in ATL patients. The mechanism underlying this difference is unknown but may be due to differences in the developmental stage of T cells at the time of infection. Indeed, HTLV-1 infection in a different humanized mouse model, generated by intrahepatic transplantation of human CD34+ stem cells into Rag2−/−γc−/− mice, induced formation of thymomas/lymphomas in mature CD4 T cells.17 In this case, HTLV-1 infection was carried out 4 and 8 weeks after transplantation of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells, giving the human immune system time to develop. Thus the infection of CD34+ stem cells per se does not appear to be sufficient for the induction of mature CD25+ T cell malignancies and may require more developed lymphoid cells or a more appropriate microenvironment capable of supporting cell development.

Furthermore, HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice almost exclusively developed leukemia, whereas HTLV-1 infection in the other humanized mouse models described above preferentially induced formation of lymphoma or thymoma. The reason for this difference is not clear but may stem from differences in the timing of T-cell infection. IBMI-huNOG mice were infected after the human hematopoietic system had been fully established, while in the other systems the infection was carried out before or shortly after stem cell transplantation.

In addition to leukemic growth of CD25+ T cells, we also observed formation of flower cells in the peripheral blood of infected mice at later time points postinfection (>16 wpi). Although transformed T cells derived from Tax-transgenic mice were found to exhibit similar morphology,15 none of the animal models described so far had recapitulated this pathology. Clonal analysis performed as part of this study demonstrated that the expansion of CD25+ T-cell clones preceded the appearance of flower cells in periphery, suggesting a sequence of events that occurs during development of the malignancy. Thus, chronological analysis of genetic and/or biochemical events in infected T cells from this mouse model should provide substantial information regarding the development of ATL.

We detected HLA-restricted CTLs against Tax protein of HTLV-1, as demonstrated in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1–infected carriers,43 confirming the presence of an acquired immune response. Furthermore, the frequency of CTLs in CD8 T-cell populations were inversely correlated with the number of infected T cells in the spleen of humanized mice, similar to observations in HTLV-1–infected individuals.43 The presence of functional T cells was also supported by the production of IgG antibodies specific to HTLV-1. Although humanized mice established by the transplantation of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells have been reported to produce antibodies against specific pathogens such as EBV,22 HIV-1,21 and DENV,50 class switching from IgM to IgG was observed in only a few cases, likely due to immature T-cell development. In the IBMI-huNOG system, however, IgG production against HTLV-1 structural protein was observed after biphasic induction of antibodies after 8 weeks, indicating a functional interaction between CD4 T cells and B cells specific for viral antigens. Taken together, these data demonstrate induction of an adaptive immune response against HTLV-1 in HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mice, which may play an important role as selective pressure in the expansion of malignant T-cell clones.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the HTLV-1–infected IBMI-huNOG mouse represents a novel model that will facilitate elucidation of the molecular mechanism of in vivo development of ATL. Moreover, our model can also be used to develop and evaluate novel preclinical therapies that target viral gene products or cellular molecules critical for viral replication as well as evaluate the efficacy of vaccine candidates to prevent viral expansion in vivo.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs R. Tatsumi and Y. Adachi for advice in establishing humanized mice and assistance with the pathological analysis, respectively. The authors are grateful to the Japanese Red Cross Kinki Cord Blood Bank for providing the samples used in this study.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research C from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grants 21590515 and 24590562) (J.F.); a MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities; and Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (grant 24171601) (T.U.) (grant 23211801) (M. Tanaka).

Authorship

Contribution: K.T. and J.F. designed the research; K.T. and R.X. established and maintained humanized mice; K.T., R.X., M. Tei and T.U. carried out experiments; M. Tanaka was involved in the IL-PCR analysis; K.T., R.X., M. Tei, and J.F. analyzed results; N.T. performed statistical analysis; K.T. designed the figures; and K.T. and J.F. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jun-ichi Fujisawa, Department of Microbiology, Kansai Medical University, 2-5-1 Shin-machi, Hirakata, Osaka 573-1010, Japan; e-mail: fujisawa@hirakata.kmu.ac.jp.

![Figure 1. Generation of IBMI-huNOG mice and T-cell development in periphery. (A) Development of human leukocytes in bone marrow of IBMI-huNOG mice. Bone marrow cells from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 20) at 1 mpt were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for expression of human CD45, CD19, and CD45, and mouse CD45 markers. Representatives (left) and the percentage of indicated markers (right) are shown. All cell populations were gated on mononuclear bone marrow cells. (B) Time course of human leukocyte development in the peripheral blood of IBMI-huNOG mice. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 40 for each time point) were stained for human CD45 at each time point. Box plots represent medians ± 1.5 IQR. (C) Increased number of human lymphocytes in IBMI-huNOG mice. Absolute numbers of human CD45+ and CD3+ cells in peripheral blood were determined by FACS analysis at each time point (n = 40 for each time point). (D) CD4-CD8 ratio in peripheral blood T cells. The CD4-CD8 ratio was calculated as follows: [(CD4 T-cell numbers per µL)/(CD8 T-cell numbers per µL)] (n = 40). (E) Sustained composition of human leukocytes in peripheral blood. PBMCs from IBMI-huNOG mice (n = 8) were stained for human CD45, CD3, and CD19. Results are presented as mean percentages of human CD45+ cells.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/3/10.1182_blood-2013-06-508861/4/m_346f1.jpeg?Expires=1769086824&Signature=xuhhktNK0CX9O55WWs7a~M6ck383biFEjFqyd0vv0-fhG3GaBuQ1gtcYGnEZGRhjFIAd1tDJj5hZW3yTs30IkYVeBDHZxfPYHfZ3nrG3rCYDE9llXjwq9P7053Ozz9IoKC8BuqaSn-UL7O0laqEwgip7bFPM1UxbOWfzt4b6YONrOt-4YkPkXSHq8UeedhzgGX2awkLTrWe03dJvTHR5c8noA2PVS0nDmuqPXLFLCqkqxMd9yFzo-POBZKGxTdJYsGBBvtTLGJpBTaZwvbJCW47NZeumZopcLrU77vWRBLmL8KYAat8bHma6fGxTdu-kPO0PO57Rp2WoDTqMz5QAJQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal