Abstract

Natural killer T (iNKT) cells can help mediate immune surveillance against tumors in mice. Prior studies targeting human iNKT cells were limited to therapy of advanced cancer and led to only modest activation of innate immunity. Clinical myeloma is preceded by an asymptomatic precursor phase. Lenalidomide was shown to mediate antigen-specific costimulation of human iNKT cells. We treated 6 patients with asymptomatic myeloma with 3 cycles of combination of α-galactosylceramide–loaded monocyte-derived dendritic cells and low-dose lenalidomide. Therapy was well tolerated and led to reduction in tumor-associated monoclonal immunoglobulin in 3 of 4 patients with measurable disease. Combination therapy led to activation-induced decline in measurable iNKT cells and activation of NK cells with an increase in NKG2D and CD56 expression. Treatment also led to activation of monocytes with an increase in CD16 expression. Each cycle of therapy was associated with induction of eosinophilia as well as an increase in serum soluble IL2 receptor. Clinical responses correlated with pre-existing or treatment-induced antitumor T-cell immunity. These data demonstrate synergistic activation of several innate immune cells by this combination and the capacity to mediate tumor regression. Combination therapies targeting iNKT cells may be of benefit toward prevention of cancer in humans (trial registered at clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00698776).

Key Points

Broad immune activation after a combination of lenalidomide and a-GalCer–loaded dendritic cells.

Proof of principle for harnessing NK T cells to prevent cancer in humans.

Introduction

Natural killer T (NKT) cells are distinct innate CD1d-restricted T cells that recognize lipid antigens.1 The best-studied subset of NKT cells in both mice and humans are type I NKT cells that express an invariant T-cell receptor. Several studies have described potent antitumor properties of iNKT cells in preclinical models and iNKT cells have also been implicated in immune surveillance against both spontaneous as well as carcinogen-induced murine tumors.2,3 While iNKT cells can mediate lysis of tumor cells, their antitumor effects likely depend in large part on their ability to activate other immune cells such as NK and dendritic cells (DCs) and recruit adaptive immunity as well as mediate antiangiogenesis.4-6 α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) is a potent prototypic ligand for both human and murine iNKT cells.7 The availability of clinical-grade α-GalCer (KRN7000; KHK) allowed testing of iNKT-targeted approaches in humans.8 Initial studies with injection of soluble KRN7000 led to only modest effects in humans.9-11 Preclinical studies suggested that targeting α-GalCer to DCs led to superior activation of NKT cells in vivo.12 In a prior study, we have shown that the injection of α-GalCer–loaded human DCs led to a clear increase in circulating iNKT cells in vivo.13 However, these cells were still functionally deficient and, importantly, little activation of downstream innate immune function (including NK cells) was observed.

It is now clear that nearly all cases of clinical myeloma (MM) are preceded by an asymptomatic precursor state, including a phase termed as asymptomatic multiple myeloma (AMM).14 Patients with AMM are currently observed but carry high risk for progression to clinical MM requiring therapy. Strategies to prevent clinical MM may therefore have a major impact on disease-related morbidity and mortality.14 In prior studies, we have shown that progression from precursor to clinical MM is associated with progressive dysfunction of iNKT cells in vivo.15 Myeloma is an attractive tumor for NKT-targeted approaches because tumor cells commonly express CD1d and are sensitive to lysis by both NKT as well as NK cells.15,16 In the past decade, incorporation of immunomodulatory drugs such as lenalidomide (LEN) into clinical care has improved outcome in human MM.17 An important property of these drugs is providing costimulation of both human T cells as well as NKT cells in culture in an antigen-dependent manner.18-20 Therefore, we hypothesized that the combination of LEN with α-GalCer–loaded DCs will lead to synergistic activation of innate lymphocytes in vivo and mediate antitumor effects in the preventive setting. As LEN alone has some single-agent activity in MM,21 we chose to test a LEN dose of 10 mg/d, which is lower than the usual starting dose (25 mg/d) in MM, so that we could glean potential synergy between these approaches. We reasoned that even short-term exposure to the combination may allow antitumor effects that may be clinically meaningful and potentially delay or avoid the need for conventional chemotherapy.

Methods

Study design and eligibility

The study design was a single-arm open-label trial (NCT00698776) to test the tolerability of the combination of monocyte-derived DCs loaded with KRN7000 (DC-KRN7000) and LEN in patients with asymptomatic myeloma (AMM). Patients with previously untreated AMM based on International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria were eligible.22 Presence of measurable disease was defined as serum M protein > 1 g/dL, urine M spike > 200 mg/d, measurable plasmacytoma, or > 10% plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy. Other eligibility criteria included age > 18 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score 0-2, consent to participate in the RevAssist program, negative pregnancy test in females of childbearing potential, and ability to take aspirin for prophylactic anticoagulation. Laboratory based inclusion criteria were absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1500/μL, platelets ≥ 100 000/μL, hemoglobin ≥ 8.0 g/dL, serum creatinine ≤ 2.0 mg/dL, serum transaminases < 5 times upper limit of normal, bilirubin < 1.5 times upper limits of normal, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio ≤ 2, and oxygen saturation on room air by pulse oxymetry ≥ 90%. Exclusion criteria were the presence of solitary plasmacytoma, uncontrolled infection, another active malignancy, immediate need for chemotherapy, New York Heart Association class III or IV, existing > grade 2 neuropathy, venous thromboembolism within 3 months or documented hypercoagulable state, active systemic autoimmunity, active hepatitis B/C, prior history of HIV infection, or pregnant or nursing women. All patients signed an informed consent per the Declaration of Helsinki that was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board, and the study was conducted under an Investigational New Drug application approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Treatment and monitoring schema

After screening and registration, patients underwent a 2-hour steady-state leukapheresis for the collection of DC progenitors. Patients were treated with a fixed dose of DCs (10 million DCs) injected intravenously in combination with LEN. Patients received 3 28-day cycles of therapy with LEN (10 mg/d) administered orally for 21 days followed by 7 days' rest and DC injection on day 8 of each cycle. Patients were evaluated on days 1, 7, and 14 of each cycle. Clinical activity was assessed 30 days after completion of all protocol therapy.

Generation and administration of KRN7000-loaded DCs

KRN7000-loaded mature DCs were generated from blood monocytes as previously described.13 Leukapheresis packs were shipped to Argos Therapeutics for manufacturing of DCs. Briefly, monocytes were isolated by elutriation and then cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL4. DCs were pulsed with 100 ng/mL KRN7000 on day 6 of culture and matured using a cocktail of inflammatory cytokines as in the previous trial.13 KRN7000-loaded DCs were cryopreserved in aliquots and each dose was shipped individually to Yale before administration. Release criteria for DCs were negative bacterial and fungal cultures, negative PCR for mycoplasma, viability of > 60%, mature DC phenotype with > 50% cells expressing CD83, and endotoxin < 30 EU/mL. Each dose of vaccine was thawed at bedside before intravenous administration. Patients were monitored for 4 hours after first DC dose for infusion-related toxicity and then for 2 hours for subsequent doses.

Immune monitoring

Immune monitoring was carried out using blood samples. Blood samples for immune monitoring were obtained before and at days 7 and 14 of each cycle, as well as 30 days after completion of all therapy. Evaluation of tumor response was performed at 30 days after completion of all protocol therapy.

Analysis of NKT cells

Numbers of NKT and their subsets were monitored by multiparameter flow cytometry. Detection of iNKT cells was based on the expression of invariant TCR (Vα24/Vβ11) and confirmed with staining for CD1d multimer loaded with α-GalCer, as described. Staining for Vα24/Vβ11 on αGalCer-CD1d dimer+ cells were monitored to track Vα24+Vβ11+ and Vα24−Vβ11+ subsets.

Analysis of NK cells

Number of NK (CD3−CD56+) cells and their subsets (CD16+CD56lo and CD16−CD56hi) were analyzed by flow cytometry. Activation of NK cells was examined by flow cytometry based on the expression of activating receptors NCR p46 and NKG2D.

Analysis of T-cell responses

Numbers of CD4 and CD8+ T cells were monitored by flow cytometry. To detect the cytokine profile of T cells, PBMCs were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) plus ionomycin (1μM) and then analyzed for the presence of intracellular cytokines (IFNγ, IL2, IL4, and IL17A) by flow cytometry as described.23 To monitor antigen-specific T cells, PBMCs were stimulated as described24 with an overlapping peptide library derived from SOX2 (an antigen previously implicated in antimyeloma immunity) or an antigenic peptide mix derived from cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, and influenza (CEF) viral antigens. After overnight culture, supernatants were harvested and analyzed for the level of interferon-γ inducible protein-10 (IP10) by Luminex analysis.

Cytokine multiplex analysis

To evaluate systemic changes induced by therapy, plasma from several time points was analyzed for the level of 39 cytokines and chemokines by Luminex using the protein Miliplex MAP kit (39 plex-Human cytokine kit, Milipore), as described.13

Statistical analysis

Data from pre- and posttherapy assays were compared using the Student t test or Mann-Whitney test. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Six eligible patients with asymptomatic myeloma were treated with 3 cycles of low-dose LEN and α-GalCer loaded mature monocyte-derived DCs in this trial. Study schema is shown in Figure 1. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1, and the phenotype of infused DCs is shown in Table 2. There was no > grade 2 acute toxicity related to DC infusion in any patient. One patient (P1) developed grade 3 urticaria within the first week of initiating LEN but was managed successfully with interruption and further dose reduction of LEN with resolution of toxicity. Another patient (P5) developed transient asymptomatic (grade 1) trigeminy before receiving DC vaccine in cycle 2. This was thought to be possibly related to LEN25 and he completed cycle 3 without LEN. Thus, this combination approach was well tolerated with no unanticipated toxicities.

Study schema. All patients underwent leukapheresis > 2 weeks before initiating therapy to harvest DC progenitors. Treatment protocol consisted of 3 cycles of lenalidomide (10 mg/d) for 3 weeks followed by 1 week of rest. KRN7000 DCs were infused on day 7 of each cycle.

Study schema. All patients underwent leukapheresis > 2 weeks before initiating therapy to harvest DC progenitors. Treatment protocol consisted of 3 cycles of lenalidomide (10 mg/d) for 3 weeks followed by 1 week of rest. KRN7000 DCs were infused on day 7 of each cycle.

Patient characteristics

| Patient no. . | Age, y . | Sex . | Race . | > CTC grade 2 protocol-related adverse event . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 60 | Female | White | Grade 3 urticaria* |

| P2 | 65 | Male | White | None |

| P3 | 67 | Female | White | None |

| P4 | 66 | Male | White | None |

| P5 | 73 | Male | White | None |

| P6 | 62 | Male | Hispanic | None |

| Patient no. . | Age, y . | Sex . | Race . | > CTC grade 2 protocol-related adverse event . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 60 | Female | White | Grade 3 urticaria* |

| P2 | 65 | Male | White | None |

| P3 | 67 | Female | White | None |

| P4 | 66 | Male | White | None |

| P5 | 73 | Male | White | None |

| P6 | 62 | Male | Hispanic | None |

CTC indicates Common Toxicity Criteria; and DC, dendritic cell.

Related to lenalidomide as it preceded DC vaccine.

Phenotype of KRN7000-loaded DCs

| Subject ID . | P1, % . | P2, % . | P3, % . | P4, % . | P5, % . | P6, % . | Mean, % . | SD, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final product imm-phenotype | ||||||||

| CD209 | 97 | 82 | 96 | 88 | 95 | 85 | 91 | 6 |

| CD14 | 13 | 0 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 |

| CD83 | 87 | 97 | 96 | 95 | 92 | 96 | 94 | 4 |

| HLA-DR | 94 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 2 |

| Subject ID . | P1, % . | P2, % . | P3, % . | P4, % . | P5, % . | P6, % . | Mean, % . | SD, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final product imm-phenotype | ||||||||

| CD209 | 97 | 82 | 96 | 88 | 95 | 85 | 91 | 6 |

| CD14 | 13 | 0 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 |

| CD83 | 87 | 97 | 96 | 95 | 92 | 96 | 94 | 4 |

| HLA-DR | 94 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 2 |

DC indicates dendritic cell; and imm, immunophenotype.

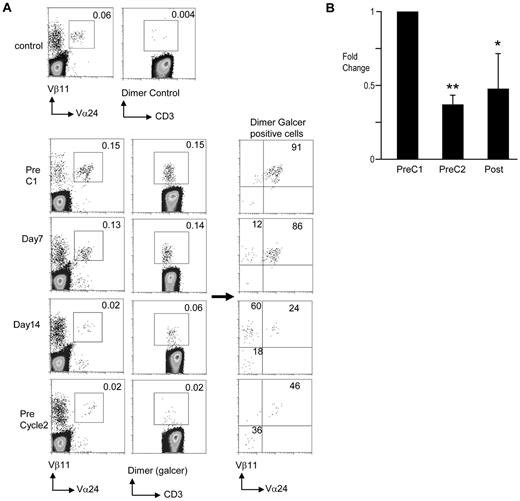

In contrast to prior studies wherein the injection of KRN7000-loaded DCs as a single agent led to a clear increase in circulating iNKT cells,13 combination therapy of DCs with LEN led to a treatment-emergent decline in measurable circulating iNKT cells, consistent with activation-induced effect (Figure 2). The decline in circulating NKT cells occurred as early as postcycle 1 and persisted throughout therapy (Figure 2B). The loss of circulating NKT cells after DC vaccine was particularly prominent for classic Vα24+Vβ11+ iNKT cells, and accordingly the proportion of the CD1d−GalCer+Vα24−Vβ11+ subset13,26 increased at 1-week post-DC vaccine (Figure 2A). It is notable that both of these subsets of α-Galcer-CD1d multimer+ T cells were mobilized into circulation after injection of KRN7000 DCs in a prior clinical trial.13 Therefore, this may represent differential kinetics of activation-induced effects. Together, these data show that the combination of LEN and α-GalCer–loaded DCs, as in this study, leads to a treatment-emergent decline in measurable circulating iNKT cells in vivo.

Changes in NKT cells. The presence of NKT cells was monitored by flow cytometry. PBMCs obtained from patients before starting therapy (PreC1), days 7 and 14 of cycle 1, before starting cycle 2 (PreC2), and at the completion of therapy (Post) were analyzed for the presence of iNKT cells using flow cytometry. The cells were stained with anti-CD3, Vα24, and Vβ11 antibodies. PBMCs were also analyzed using CD1d dimer either unloaded (Dimer control) or loaded with α-Galcer (Dimer Galcer). (A) Data from a representative patient during first cycle of therapy. (B) Summary of pooled data. Only patients with frequency of NKT cells above 0.01% at baseline were used to reliably estimate posttreatment decline in NKT cells. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Changes in NKT cells. The presence of NKT cells was monitored by flow cytometry. PBMCs obtained from patients before starting therapy (PreC1), days 7 and 14 of cycle 1, before starting cycle 2 (PreC2), and at the completion of therapy (Post) were analyzed for the presence of iNKT cells using flow cytometry. The cells were stained with anti-CD3, Vα24, and Vβ11 antibodies. PBMCs were also analyzed using CD1d dimer either unloaded (Dimer control) or loaded with α-Galcer (Dimer Galcer). (A) Data from a representative patient during first cycle of therapy. (B) Summary of pooled data. Only patients with frequency of NKT cells above 0.01% at baseline were used to reliably estimate posttreatment decline in NKT cells. *P < .05; **P < .01.

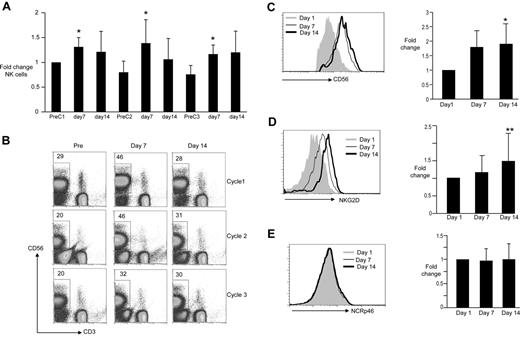

Activation of NKT cells can lead to NK activation in vivo.5 LEN or thalidomide therapy has also been shown to lead to expansion of NK cells.27,28 A cyclic pattern of increase in circulating NK cells was observed with each cycle, returning close to baseline before the next cycle (Figure 3A-B). Numbers of NK cells typically peaked at 7 days after initiation of cycle, suggesting that this primarily reflected the effect of LEN. Changes in NK numbers were also associated with an increase in CD56 expression on NK cells with similar kinetics, again consistent with this being a primary LEN effect (Figure 3C). There were no changes in the expression of NCRp46 (Figure 3E), but initiation of therapy also led to an increase in the expression of NKG2D on NK cells, which increased progressively from day 7 to day 14 of therapy (Figure 3D). Together, these data suggest that the combination of LEN and DC (α-GalCer) led to clear modulation of NK cells in vivo, which represents a combination of effects that can be ascribed largely to LEN alone, as well as those (such as NKG2D up-regulation) that appear to increase progressively in response to the combination.

Changes in NK cells. PBMCs obtained from patients before staring therapy (PreC1), before cycle 2 (PreC2), and before cycle 3 (PreC3) as well as day 7 and 14 of each cycle were analyzed for the presence of CD3−, CD56+ NK cells using flow cytometry. Changes in surface expression of CD56, NCRp46, as well as NKG2D on the surface of the CD3−, CD56+ NK cells were also monitored by flow cytometry. (A) Summary of pooled data for frequency of circulating NK cells during therapy, reflected as fold change on day 7 and 14 compared with baseline; *P < .05. (B) Representative data from a single patient. (C) Changes in expression of CD56 on NK cells during cycle 1. (Left panel) Data from a representative patient. (Right panel) Summary of pooled data from all patients; P < .05. (D) Changes in expression of NKG2D on NK cells during cycle 1. (Left panel) Data from a representative patient. (Right panel) Summary of pooled data from all patients; ** P = .07. (E) Changes in expression of NCRp46 on NK cells during cycle 1. (Left panel) Data from a representative patient. (Right panel) Summary of pooled data from all patients.

Changes in NK cells. PBMCs obtained from patients before staring therapy (PreC1), before cycle 2 (PreC2), and before cycle 3 (PreC3) as well as day 7 and 14 of each cycle were analyzed for the presence of CD3−, CD56+ NK cells using flow cytometry. Changes in surface expression of CD56, NCRp46, as well as NKG2D on the surface of the CD3−, CD56+ NK cells were also monitored by flow cytometry. (A) Summary of pooled data for frequency of circulating NK cells during therapy, reflected as fold change on day 7 and 14 compared with baseline; *P < .05. (B) Representative data from a single patient. (C) Changes in expression of CD56 on NK cells during cycle 1. (Left panel) Data from a representative patient. (Right panel) Summary of pooled data from all patients; P < .05. (D) Changes in expression of NKG2D on NK cells during cycle 1. (Left panel) Data from a representative patient. (Right panel) Summary of pooled data from all patients; ** P = .07. (E) Changes in expression of NCRp46 on NK cells during cycle 1. (Left panel) Data from a representative patient. (Right panel) Summary of pooled data from all patients.

Prior studies have suggested the capacity of iNKT cells to mediate the activation of myeloid cells.29,30 Analysis of phenotype of monocytes revealed an increase in CD16 expression on CD14+ cells during therapy (Figure 4A). There were no consistent differences in the numbers of CD14−CD11b+ cells. While evaluation of eosinophils was not a part of planned immune monitoring, most patients were observed to develop marked and recurrent eosinophilia with each cycle, which peaked mid-cycle and declined before initiation of a new cycle (Figure 4B). To assess the systemic effects of therapy, we measured the levels of a panel of cytokines and chemokines before and after initiation of therapy. Of these, cyclic changes in soluble IL2 receptor were observed in all patients, consistent with therapy-induced immune activation (Figure 4C). Thus, in addition to NKT and NK cells, the combination therapy tested here led to effects on diverse innate cells including eosinophils and monocytes.

Changes in other innate cells and cytokines. (A) Changes in expression of CD16 on monocytes during cycle 1. PBMCs obtained from patients before starting therapy (PreC1) as well as from cycle 2 (PreC2) were analyzed for the presence of CD16 on CD14+ monocytes using flow cytometry. (Left panel) Data from a representative patient. (Right panel) Summary of pooled data from all patients. (B) Changes in eosinophils. A complete blood count was obtained weekly as part of routine care of the patients. Shown are the changes in eosinophil count as a percentage of white blood cells during therapy. (C) Changes in plasma levels of soluble IL2 receptor during therapy. Plasma obtained from blood collected on patients before starting therapy (PreC1), before starting cycle 2 (PreC2), before starting cycle 3 (PreC3), as well as days 7 and 14 of each cycle was analyzed for the presence of soluble IL2-receptor (sIL-2R) using a multiplex Luminex assay. Shown are the changes in sIL2R expressed as fold change from baseline (before starting cycle 1).

Changes in other innate cells and cytokines. (A) Changes in expression of CD16 on monocytes during cycle 1. PBMCs obtained from patients before starting therapy (PreC1) as well as from cycle 2 (PreC2) were analyzed for the presence of CD16 on CD14+ monocytes using flow cytometry. (Left panel) Data from a representative patient. (Right panel) Summary of pooled data from all patients. (B) Changes in eosinophils. A complete blood count was obtained weekly as part of routine care of the patients. Shown are the changes in eosinophil count as a percentage of white blood cells during therapy. (C) Changes in plasma levels of soluble IL2 receptor during therapy. Plasma obtained from blood collected on patients before starting therapy (PreC1), before starting cycle 2 (PreC2), before starting cycle 3 (PreC3), as well as days 7 and 14 of each cycle was analyzed for the presence of soluble IL2-receptor (sIL-2R) using a multiplex Luminex assay. Shown are the changes in sIL2R expressed as fold change from baseline (before starting cycle 1).

Although the primary intent of this study was to evaluate the safety and feasibility of this “first in human” combination, evaluation of tumor-associated markers permitted the assessment of clinical antitumor effects. Three of 4 patients with a measurable M spike (> 1 g/dL) at baseline experienced a reduction in tumor-associated monoclonal Ig with protocol therapy, consistent with a clinical antitumor effect (Figure 5A). The only patient with measurable disease that did not experience reduction in M spike had received very little LEN therapy because of grade 3 urticaria. Although maximal reduction in tumor-associated Ig was seen toward the completion of planned therapy, the clinical effects extended well beyond the completion of therapy. Interestingly, in one patient (P5), persistent decline in tumor-derived serum-free immunoglobulin light chains (FLCs) was observed even in the setting of a recurrent increase in monoclonal Ig after completion of therapy (Figure 5B). As increased FLCs have been typically associated with an aggressive phenotype in myeloma,31 this observation suggests the possibility of altered biology of the residual disease.

Clinical effects of therapy. (A) Comparison of tumor-associated monoclonal Ig (M spike) at baseline versus the value at best response. (B) Differential kinetics of M spike versus serum-free light chains in a patient (P5) with progressive increase in M spike after completion of therapy.

Clinical effects of therapy. (A) Comparison of tumor-associated monoclonal Ig (M spike) at baseline versus the value at best response. (B) Differential kinetics of M spike versus serum-free light chains in a patient (P5) with progressive increase in M spike after completion of therapy.

Although several of the effects on innate cells including NK activation and eosinophilia were strictly cyclic in relation to treatment cycles, we also explored changes in adaptive immunity during therapy. To evaluate the effect of this therapy on cytokine profiles of T cells, we analyzed the presence of T cells secreting IFNγ, IL4, IL2, and IL17 after stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. There were no consistent changes in these T cells after therapy (Figure 6A). In prior studies, we have shown that naturally occurring immunity to an embryonal stem cell–associated antigen SOX2 correlates with favorable outcome in patients with monoclonal gammopathy.24 T-cell immunity to SOX2 was detected at baseline in 2 of 3 patients with clinical response to therapy (P5, P6), while the responders did not differ from responders with reference to immunity to viral antigens (CEF peptides) at baseline (Figure 6B-C). Interestingly, transient activation of SOX2 immunity was also observed in the third patient (P2) who exhibited a clinical response, but lacked such immunity at baseline (Figure 6D). Immunity to SOX2 was not detected in the patients lacking clinical response. Thus, clinical response to therapy correlated with baseline or treatment-emergent T-cell immunity to SOX2.

Changes in T-cell immunity. (A) Changes in cytokine profile of T cells. PBMCs from pre- and posttherapy time points were thawed and stimulated with PMA and ionomycin. The percentage of CD3+ T cells expressing individual cytokines (IFNγ, IL2, IL17, and IL4) was evaluated using intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry. Shown is the fold change in cytokine production on days 7 and 14 of cycle one as well as before starting cycle 2 (PreC2) compared with cytokine production by T cells before starting therapy (preC1). (B-C) PBMCs from baseline (pretreatment) were stimulated overnight with an overlapping peptide library derived from SOX2 (B) or a pool of peptides from viral antigens (CEF) as a control (C). Reactivity to the peptide pools was assayed with the detection of IP10 in the supernatant. Stimulation index refers to fold increase in IP10 over control wells. (D) Changes in SOX2 reactivity during therapy in a patient P2 with clinical response to therapy. PBMCs were stimulated overnight with peptide pools derived from SOX2 as in panel B. After overnight culture, the presence of IP10 in supernatant was assayed using Luminex.

Changes in T-cell immunity. (A) Changes in cytokine profile of T cells. PBMCs from pre- and posttherapy time points were thawed and stimulated with PMA and ionomycin. The percentage of CD3+ T cells expressing individual cytokines (IFNγ, IL2, IL17, and IL4) was evaluated using intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry. Shown is the fold change in cytokine production on days 7 and 14 of cycle one as well as before starting cycle 2 (PreC2) compared with cytokine production by T cells before starting therapy (preC1). (B-C) PBMCs from baseline (pretreatment) were stimulated overnight with an overlapping peptide library derived from SOX2 (B) or a pool of peptides from viral antigens (CEF) as a control (C). Reactivity to the peptide pools was assayed with the detection of IP10 in the supernatant. Stimulation index refers to fold increase in IP10 over control wells. (D) Changes in SOX2 reactivity during therapy in a patient P2 with clinical response to therapy. PBMCs were stimulated overnight with peptide pools derived from SOX2 as in panel B. After overnight culture, the presence of IP10 in supernatant was assayed using Luminex.

Discussion

These data provide the first example of targeting human NKT cells toward prevention of clinical cancer. Combination of KRN7000 DCs and LEN led to activation of several aspects of innate immunity including NKT, NK, monocytes, as well as eosinophils. Such a broad immune activation may be critical for harnessing innate immunity toward cancer prevention. The effects on innate immunity in this study are quite different from those observed previously after injection of KRN7000 DCs alone, suggesting that pharmacologic costimulation, as provided here by LEN,18-20 may be essential to optimally harness human NKT cells against tumors.32 Other costimulatory strategies that may also be of interest in this regard include combinations with checkpoint blockade inhibitors.32

These data also have implications for understanding and optimizing the immune-modulatory effects of LEN. The data clearly show that even low-dose LEN can lead to clear activation of NK cells in patients with asymptomatic MM with up-regulation of CD56 and NKG2D. Importantly, the effects of LEN on NK cells are rapid and primarily occur during treatment cycles, suggesting that prior studies evaluating the effects on NK cells only between cycles of therapy (such as before a new cycle with intermittent dosing) or in combination with with dexamethasone in the setting of advanced MM may have grossly underestimated these effects.27,28,33 The cyclic nature of NK activation may be particularly relevant for optimal design of combination therapies. For example, NK activation with up-regulation of NKG2D, along with up-regulation of CD16 on monocytes in vivo supports combination with antitumor monoclonal antibodies to improve antibody-dependent cytotoxicity.34-36 Such combinations are indeed showing promise in both lymphoma and myeloma and are now in advanced-phase clinical testing.

Several aspects of these data suggest that KRN7000-DCs and LEN have synergistic effects toward the activation of innate immunity, as suggested in the initial preclinical studies.19,20 For example, injection of DCs led to further up-regulation of NKG2D on NK cells. The degree of eosinophilia observed in these patients has also not been described in the context of prior extensive experience with LEN, typically used at higher doses in human myeloma. The close temporal association between NKG2D up-regulation and eosinophilia as described here is highly reminiscent of the recent findings in mice linking NKG2D ligands, innate lymphoid stress surveillance response, and atopy.37,38 The combination approach described here may therefore represent a novel strategy to harness NKG2D-mediated lymphoid stress surveillance response in humans. We could not correlate the induction of eosinophilia with any of the Th2 cytokines (IL4, IL5, IL13) tested (data not shown). The temporal correlation of eosinophilia with serum levels of soluble IL2 receptor suggests a possible pathogenic link with T-cell activation, which needs further investigation. IL2 therapy of human melanoma has been described to lead to an increase in eosinophils.39 The observed prominence of eosinophilia is also of interest for putative role of NKT cells in regulating allergy and asthma.40

Several studies have shown that iNKT cells can link innate and adaptive immunity by mediating activation of DCs.41-43 Antitumor effects of NKT-targeted approaches may therefore also depend on adaptive immunity against tumors. It is of interest that the clinical responses in this study correlated with the presence of pre-existing or induced antitumor T-cell immunity. Further studies are needed to confirm this intriguing but preliminary correlation, suggesting a role for pre-existing T-cell immunity in efficacy of NKT-targeted approaches.

Accrual in the current trial was limited by the lack of continued access to clinical-grade KRN7000, which prevented treating additional patients in spite of observing promising clinical responses in the initial cohort as reported here. Activation of innate immunity seemed to strictly depend on continued therapy, suggesting that longer duration of therapy may be needed for deeper responses. However, an important property of an immune-based approach would be the possibility of a durable unmaintained response. Favorable toxicity profile and the use of low-dose LEN without steroids in this study nonetheless suggest that longer therapy with this combination may be clinically feasible. A Spanish trial is currently evaluating the effects of full-dose (25 mg/d) LEN and dexamethasone in AMM.44 The US cooperative groups are also currently evaluating full-dose LEN in AMM. However, these approaches carry significant risk for treatment-related toxicity and in some instances involve long-term exposure to steroids. If the clinical activity of the current combination can be confirmed in a larger cohort, it may be an attractive strategy for further evaluation as a preventive approach in MM. The availability of clinical-grade iNKT ligands in the near future should allow re-exploration of NKT-targeted therapies in humans.45

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the referring physicians and nursing staff for their help with this study.

M.V.D. and K.M.D. are supported in part by funds from the National Institutes of Health and the Doris Duke and Dana foundations (to K.M.D.). This study was also supported in part by funds from Kirin Breweries and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Translational Research Program.

This manuscript is dedicated to the loving memory of Ralph M. Steinman, for his support and encouragement of this study.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.R. and N.N. performed clinical research; L.Z., S.N., and R.S. performed immune monitoring; T.M. and F.M. manufactured dendritic cells; K.M.D. supervised and analyzed immune monitoring and overall research; and M.V.D. designed, supervised, and analyzed research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.M. and F.M. are employees of Argos Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Madhav V. Dhodapkar, MD, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St, New Haven, CT 06510; e-mail: madhav.dhodapkar@yale.edu.

References

Author notes

J.R. and N.N. contributed equally to this work.

K.M.D. and M.V.D. share senior authorship.