Abstract

The phenotype and function of cells enriched in tumor-propagating activity and their relationship to the phenotypic architecture in multiple myeloma (MM) are controversial. Here, in a cohort of 30 patients, we show that MM composes 4 hierarchically organized, clonally related subpopulations, which, although phenotypically distinct, share the same oncogenic chromosomal abnormalities as well as immunoglobulin heavy chain complementarity region 3 area sequence. Assessed in xenograft assays, myeloma-propagating activity is the exclusive property of a population characterized by its ability for bidirectional transition between the dominant CD19−CD138+ plasma cell (PC) and a low frequency CD19−CD138− subpopulation (termed Pre-PC); in addition, Pre-PCs are more quiescent and unlike PCs, are primarily localized at extramedullary sites. As shown by gene expression profiling, compared with PCs, Pre-PCs are enriched in epigenetic regulators, suggesting that epigenetic plasticity underpins the phenotypic diversification of myeloma-propagating cells. Prospective assessment in paired, pretreatment, and posttreatment bone marrow samples shows that Pre-PCs are up to 300-fold more drug-resistant than PCs. Thus, clinical drug resistance in MM is linked to reversible, bidirectional phenotypic transition of myeloma-propagating cells. These novel biologic insights have important clinical implications in relation to assessment of minimal residual disease and development of alternative therapeutic strategies in MM.

Key Points

CD19−CD138+ and CD19−CD138− myeloma cells represent interconvertible phenotypic and functional states and share myeloma-propagating activity.

Nongenetic, including epigenetic, diversification of myeloma-propagating cells is linked to clinical drug resistance.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable plasma cell (PC) malignancy of the bone marrow (BM). Although acquired genetic events and the tumor microenvironment are well-established regulators of myeloma cell survival and proliferation pathways, the identity and functional properties of the myeloma-propagating cells have been a matter of controversy.1,2

The terminal differentiation of normal mature B lymphocytes to immunoglobulin (Ig)–secreting PCs entails conversion of antigen-naive to antigen-experienced B cells in the germinal center of secondary lymphoid organs and their subsequent differentiation to either memory B cells or PCs.3,4 Each stage of B-cell differentiation can be defined by surface markers with naive and memory B cells expressing CD19 and terminally differentiated normal and malignant PCs, but not B cells, expressing CD138 (Syndecan-1).5,6

Given this linear B-cell lineage developmental process, it was suggested that myeloma cell growth is sustained by a minority of cells more immature than the PC. This hypothesis is supported by the presence of CD19+CD138− clonotypic B cells (ie, cells sharing the same Ig heavy chain [IgH] complementarity region 3 [CDR3] sequence with the myeloma PCs) in peripheral blood (PB) and BM of patients with MM.7-10 Indeed, because CD138− but not CD138+ PCs were found to lead to myeloma engraftment in NOD/SCID mice, it was proposed that CD138− cells were the principal myeloma-propagating or “myeloma stem” cells11-14 Earlier studies, though, using a huSCID mouse model, had concluded that mature PCs (defined as CD38hiCD45−), and not the CD19+ B-cell fraction, contained the entire myeloma-propagating activity,15 whereas more recently, CD19−CD138− as well as CD138+ cells engrafted SCID-rab mice with myeloma.16 Furthermore, whereas earlier studies reported that the myeloma side population is enriched in clonogenic activity and identifies with CD138− but not CD138+ myeloma cells,13 recent evidence shows that both CD138+ and CD138− cells are included in the highly clonogenic myeloma side population.17 Whether these discrepancies result from different animal models and phenotypic definitions of PC is not clear. Here, through a detailed phenotypic and genetic analysis of primary human myeloma cells and a prospective, dynamic ex vivo and in vivo study of the constituents of the myeloma cellular architecture, we show that a phenotypic and functional interconvertible state between CD138+ and CD138− cells underpins myeloma-propagating activity and clinical drug resistance.

Methods

Patient and normal donor BM and PB samples

Patient BM and PB samples were obtained after written informed consent and appropriate institutional ethics committee approval. Patient characteristics are shown in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Diagnosis, remission, and relapse of MM were defined according to previously described criteria.18 Normal BM samples were surplus material from cryopreserved BM harvests, collected from healthy sibling adult donors, for use in allogeneic transplantation. Cells were collected and stored in the John Goldman Center for Cellular Therapy at the Hammersmith Hospital, under Joint Accreditation Committee–ISCT and EBMT-approved procedures and released with donor's written informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

IgH CDR3 characterization of the myeloma clone and patient-specific IgH CDR3 quantitative PCR for myeloma clonotypic cells

The IgH CDR3 characterization of the myeloma clone was performed as previously described.19 A customized genomic DNA quantitative PCR assay was used for detection and quantification of clonotypic cells (supplemental Figure 1C). For this purpose, patient-specific IgH CDR3 forward primer was designed in the D-N2-JH area. IgH hydrolysis probes (TaqMan) labeled with FAM in 5′-end and with TAMRA in the 3′-end were complementary to the 3′-end of the JH exon, as previously published.20 The reverse primer for quantitative PCR was designed complementary to the intron downstream the JH gene segment. Unlike other B-cell malignancies, we found that in MM this intronic area is usually heavily affected by somatic hypermutation. Therefore, this intronic area was amplified in each case with a PCR using the patient-specific IgH CDR3 forward primer and a JH reverse primer complementary to the downstream JH gene. The PCR product was characterized by nucleotide sequencing, and a patient-specific reverse primer was designed to improve the efficiency and specificity of quantitative PCR (supplemental Figure 1D). In selected cases, a patient-specific probe had to be designed for the same reasons. Quantitative PCR sensitivity was tested using serial dilutions of patient CD138+ cell gDNA into gDNA extracted from a pool (n = 10) of normal donor B cells. The ΔΔCq method was used for the relative quantitation of the myeloma clonotypic cells within the flow-sorted cell populations. The reference gene used was albumin (see also supplemental Methods).

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting

BM cells and PBMCs were prepared in single-cell suspension in PBS plus 0.5% BSA solution. Nonspecific staining was reduced using a Fc blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used for dead cell exclusion. Doublet cells were excluded based on FSC-W/FSC-A values. We used 12-color flow cytometry for analysis in a BD LSRFortessa analyzer and 10-color staining for cell sorting in a BD FACSAria II cell sorter (both from BD Biosciences). The monoclonal antibodies used are listed in supplemental Methods. For cell cycle analysis, cells were first stained for surface markers followed by fixation for 30 minutes, using a fixation buffer from eBioscience. Cells were then incubated for 20 minutes in DAPI staining solution (DAPI 1 μg/mL, Triton-X 0.1%). A 355-nm UV laser in a BD LSRFortessa analyzer was used for DAPI excitation. For rhodamine 123 dye exclusion, cells were first stained for surface markers and then incubated in α-MEM culture medium plus 12.5μM rhodamine 123 for 10 minutes. Cells were then washed and placed in 37°C for 45 minutes before analysis. Data were analyzed using the FlowJo Version 7.6.5 software (TreeStar).

Xenograft assays

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice were obtained from Dr Paresh Vyas (Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance to Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and under a United Kingdom Government Home Office approved project license.

NSG mice 9-13 weeks of age were first sublethally irradiated (200 cGy) and cells were injected within the next 4-24 hours. The isolation strategy of clonotypic cells from total BM was modified, aiming to minimize exposure of transplanted cells to surface antibody labeling, especially anti-CD38. This approach was adopted to avoid opsonization and thus reduced engraftment rates as previously reported.21

CD138+ PCs were first isolated from total BM with CD138+ immunomagnetic bead selection, followed by flow sorting of the CD138hi cells to high purity (∼ 100%; see Figure 4A). Pre-PC were negatively enriched by flow sorting of the CD19−CD138−CD2−CD3−CD14−CD16−CD34−CD45− Glycophorin A− BM cells. Clonotypic B cells were flow-sorted using a CD19+CD138− gate. Cells were collected in PBS and immediately injected in doses up to 1.5 × 106 cells per animal (supplemental Table 4). In all cases, tail vein-injected cells were tested with IgH CDR3 quantitative PCR to confirm the presence and quantify the dose of clonotypic cells given (shown in supplemental Table 4). Mice were followed up for a minimum period of 24 weeks. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the murine BM, liver, and spleen and analyzed with flow cytometry. Human cells were identified as mCD45.1−hCD59+ and further tested for expression of CD138, CD38, CD56, CD19, CD20, CD200, CD319, and CD27 antigens. Engrafted cells were quantified as percentage of the mCD45.1+ murine hematopoietic cells. In addition, engraftment of human cells was confirmed with IgH CDR3 quantitative PCR, showing that the human cells found in the murine tissues were always 100% clonotypic.

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA was extracted from flow-sorted (purity > 99%) PCs and Pre-PCs using the RNeasy Plus Micro kit (QIAGEN). In all cases (n = 9, supplemental Table 5), cells were isolated from fresh BM aspirates taken at diagnosis (n = 6) or at relapse (n = 3). Extracted RNA was quantified using the Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen). RNA purity and integrity were confirmed in an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser with RNA Pico Chips. Because Pre-PC is a low-frequency population, we used the Ovation Pico WTA Systems V2 from NuGEN Technologies to efficiently produce amplified cDNA for microarrays (accession number E-MEXP-3772) starting from a 15 ng total RNA input. Amplified cDNA was then fragmented and labeled using the Encore Biotin Module (NuGEN Technologies) and hybridized on Human Gene ST1.0 Arrays (Affymetrix) at a final concentration 23 ng/μL in the hybridization mix on a GeneChip Flucidics Station 450. The arrays were scanned in a GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G with autoloader.

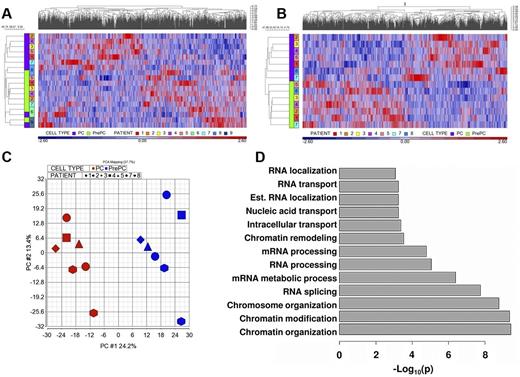

Arrays were normalized using RMA and then nonspecific filtering applied to remove probes with low variance across samples. Hierarchical clustering and heat map generation were performed using Partek on the 1000 probes showing the greatest log fold change. Differential expression analysis was applied in R/Bioconductor using the limma package22 with empirical Bayes correction. Principal component analysis was applied on the 1509 genes showing differential expression (P < .05) with the first principal component (PC1) clearly separating the Pre-PC–PC sample cell types. To enrich the set of genes for gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis, a cut on the (absolute) loadings on PC1 of 0.02 was applied, giving 1094 genes for analysis. GO term enrichment was performed using DAVID with the total set of genes on the Affymetrix HG ST 1.0 as the background. P values represent a Benjamini-Hochberg corrected modified Fisher exact test. The microarray data are deposited to Array Express with accession number E-MEXP-3772

Statistics

The Mann-Whitney and Wilcoxon sign-rank tests were used for group comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS statistics Version 17.0 software.

Modeling and relevant statistical methods, cytology, immunohistochemistry, and FISH are described in supplemental Methods.

Results

Cell of origin, phenotypic diversity and genetic characterization of the myeloma cellular architecture

The presence of low-frequency PB and BM clonotypic CD19+ B cells7-10 suggests that the cell of origin in MM is a CD19+ B lineage cell. To further address this, we analyzed in purified myeloma PCs the length of the class switch recombination Sμ-γ fusion fragment, a unique molecular event that defines transition from naive to memory B cells.23 Using long template PCR, as previously reported,24 we found a single band in all 10 cases studied (supplemental Figure 1A-B), suggesting that tumor-propagating cells in MM originate from a post-class switch recombination, germinal center-experienced B cell.

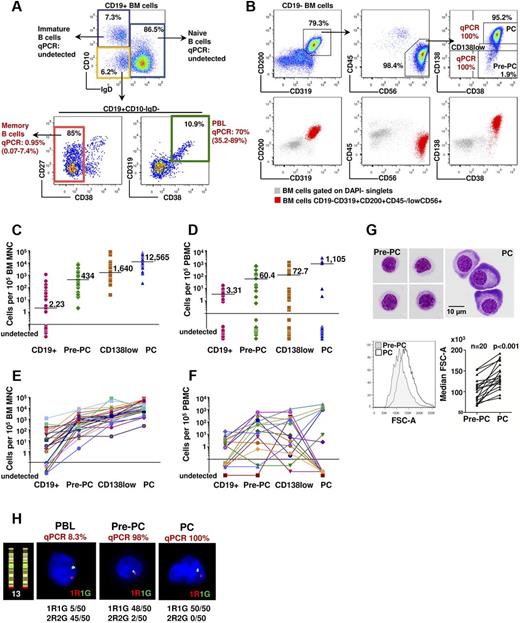

Next, we established the complete phenotypic spectrum and quantified the frequency of B-cell lineage clonotypic cells. Using a rigorous methodology combining flow sorting of populations of interest with a highly sensitive clonotypic genomic quantitative PCR assay specific for the patient-unique IgH CDR3 sequence (supplemental Figure 1C-F), we identified clonotypic CD19+ cells in both the BM and PB of patients at diagnosis, remission, and relapse (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 1G). In line with class switch recombination analysis, we found that the clonotypic architecture of MM does not include naive (CD19+IgD+) or immature (CD19+IgD−CD10+) B cells (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1G). Instead, it consists of (1) mature CD19+ B cells (Figure 1A) comprising resting memory B cells (CD19+CD10−IgD−CD27+/− CD38−) and plasmablasts (PBLs; CD19+CD10−IgD−CD38hi CD319+CD138−; Figure 1A) and (2) CD19−CD200+CD319+CD56+ cells comprising CD138+ and CD138low PCs and a previously incompletely characterized, low-frequency (∼ 3% of all clonotypic cells) CD19−CD138−CD200+CD45−/loCD319+CD56+ population we termed Pre-PCs (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 1H). Quantitation of the clonotypic subpopulations in the BM of 30 patients with MM (supplemental Table 1) showed that the frequency of clonotypic cell subsets, from CD19+ cells to CD19−CD138+ PCs, increases in a near-logarithmic manner (Figure 1C,E). Unlike in BM, Pre-PCs, but not PCs, were identified in the PB of the majority of patients (Figure 1D,F). In line with CD138 expression heterogeneity, CD138low and CD138− cells could also be identified by BM immunohistochemistry (supplemental Figure 1I-J). Notably, Pre-PCs and PCs from MM patients were morphologically distinct from each other: Pre-PCs, in contrast to the large size and the prominent Golgi apparatus of PCs, were significantly smaller with little or no visible Golgi and resembled small lymphocytes (Figure 1G).

Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the clonotypic cellular architecture in myeloma. (A) Multiparameter flow cytometry gating strategy for identification and flow sorting of CD19+ fractions (immature, naive, memory B cells, and PBLs) in the BM of patients with myeloma. Each of the indicated fractions was flow-sorted to high purity and subjected to patient-specific clonotypic genomic DNA quantitative PCR. (B) Top panel: Strategy for characterization of CD19− clonotypic populations. Sequential gating of patient BM CD200+CD319+ and CD45lo/−CD56+ cells allows identification and flow sorting of an almost entirely clonotypic hierarchy of CD138+ (PC), CD138low and CD138− (Pre-PC) cells. Bottom panel: Overlays of the CD19− clonotypic cells (red) over the total BM cells (gray) indicates that, if the traditional gating on CD138+CD38+ events was applied, it would exclude Pre-PC and CD138low cells from further analysis. (C-F) Frequency of clonotypic fractions in BM mononuclear cells (n = 30 patients; C,E) and PBMCs (n = 21 patients; D,F) of patients with myeloma shown as a cohort (C-D) or in individual patients (E-F). Horizontal bars represent median values excluding cases with undetectable clonotypic cells. (G) Top: May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining of flow-sorted Pre-PCs and PCs (original magnification ×1000). Bottom: Histogram and median FSC-A values of Pre-PCs and PCs. (H) Interphase FISH analysis of chromosome 13 complement showing loss of 1 red (13q34) and 1 green signal (13q14), consistent with monosomy 13 in highly purified, flow-sorted PB PBLs, Pre-PCs, and PCs from the same patient, confirmed as enriched in clonotypic cells by quantitative PCR. Chromosome 13 ideogram and location of FISH probes are shown on the left. The upper threshold for normal results is 5%. A minimum of 50 interphase cells were scored by 2 independent analysts in a blinded fashion. The average number of total interphases examined and the number of those with 13q deletion are shown below the FISH image.

Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the clonotypic cellular architecture in myeloma. (A) Multiparameter flow cytometry gating strategy for identification and flow sorting of CD19+ fractions (immature, naive, memory B cells, and PBLs) in the BM of patients with myeloma. Each of the indicated fractions was flow-sorted to high purity and subjected to patient-specific clonotypic genomic DNA quantitative PCR. (B) Top panel: Strategy for characterization of CD19− clonotypic populations. Sequential gating of patient BM CD200+CD319+ and CD45lo/−CD56+ cells allows identification and flow sorting of an almost entirely clonotypic hierarchy of CD138+ (PC), CD138low and CD138− (Pre-PC) cells. Bottom panel: Overlays of the CD19− clonotypic cells (red) over the total BM cells (gray) indicates that, if the traditional gating on CD138+CD38+ events was applied, it would exclude Pre-PC and CD138low cells from further analysis. (C-F) Frequency of clonotypic fractions in BM mononuclear cells (n = 30 patients; C,E) and PBMCs (n = 21 patients; D,F) of patients with myeloma shown as a cohort (C-D) or in individual patients (E-F). Horizontal bars represent median values excluding cases with undetectable clonotypic cells. (G) Top: May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining of flow-sorted Pre-PCs and PCs (original magnification ×1000). Bottom: Histogram and median FSC-A values of Pre-PCs and PCs. (H) Interphase FISH analysis of chromosome 13 complement showing loss of 1 red (13q34) and 1 green signal (13q14), consistent with monosomy 13 in highly purified, flow-sorted PB PBLs, Pre-PCs, and PCs from the same patient, confirmed as enriched in clonotypic cells by quantitative PCR. Chromosome 13 ideogram and location of FISH probes are shown on the left. The upper threshold for normal results is 5%. A minimum of 50 interphase cells were scored by 2 independent analysts in a blinded fashion. The average number of total interphases examined and the number of those with 13q deletion are shown below the FISH image.

Genetic characterization of the clonotypic hierarchy by FISH confirmed the presence of oncogenic cytogenetic abnormalities [such as t(11;14), t(4;14) and del1325,26 ] in clonotypic CD19+ cells as well as in PCs and Pre-PCs of the same patient showing that these cells are part of the same malignant clone as the CD138+ PCs (Figure 1H; supplemental Figure 1K-L). Together, these data show that the clonotypic architecture in MM is phenotypically more diverse than previously appreciated and bears the typical MM oncogenic genetic hallmarks.

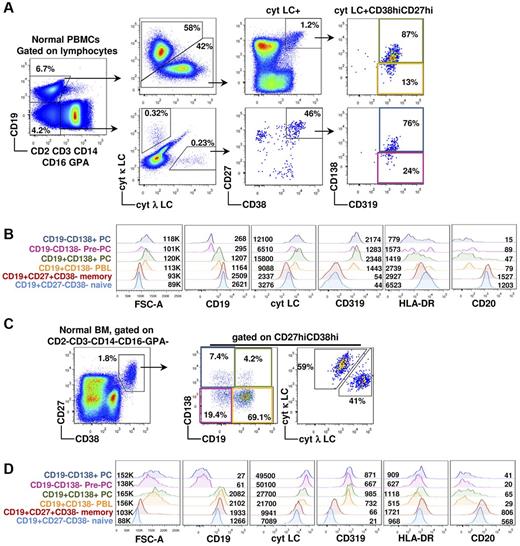

Normal counterpart of Pre-PCs in PB and BM

Previous studies demonstrated the presence of circulating CD19+ PBLs and PCs in the PB of healthy persons.6,27 These cells show strong expression of CD27 and CD38 (ie, CD19+CD38hiCD27hi). However, it is unclear whether a normal counterpart of circulating Pre-PCs (ie, CD19− B lineage cells with the CD38hiCD27hiCD319+ CD138− phenotype) exists. To address this, we performed immunophenotypic analysis of PB samples from 15 healthy donors (Figure 2A-B). As previously described,6,27 within the population that expresses cytoplasmic Ig light chains (LCs) and therefore composes bona fide B lineage cells, we identified CD19+CD38hiCD27hi CD319+ CD138− PBLs and CD138+ PCs. In addition, we identified a CD19− cytoplasmic Ig LC+ population, which was enriched in CD38hiCD27hiCD319+ cells. The majority of these cells (CD19−CD38hiCD27hiCD319+ cells) express CD138 and are therefore PCs, whereas a smaller proportion are CD138− (ie, correspond to the myeloma Pre-PC phenotype; Figure 2A-B).

CD19−CD138− Pre-PCs are a feature of the normal late B-cell development. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of the normal late B-cell development in PB (n = 15 normal donors); a representative donor sample is shown. After gating out non–B-cell lineage cells, analysis of CD19+ cells, as expected, shows a polyclonal pattern of cytoplasmic Ig LC expression (ie, expression of κ and λ chains). PBLs are identified as CD38hiCD27hiCD138− and PCs as CD38hiCD27hiCD138+ cells. For identification of Pre-PCs, gating on lineage-CD19− cells reveals a small cytoplasmic Ig LC+ population, which on sequential gating is found to be enriched in CD38hiCD27hi cells (48% in the case shown); these include CD138+ PCs and CD138− Pre-PCs. Both CD19+ PBLs/PCs and CD19− Pre-PCs/PCs are CD319+. (B) Histograms showing cell size as assessed by FSC-A and expression levels of CD19, cytoplasmic Ig LC, CD319, CD20, and HLA-DR in the above 4 populations as well as in naive and memory B cells. Numbers next to histograms represent median intensity fluorescence values. (C) Identification of PBLs, CD19+ PCs, Pre-PCs, and CD19− PCs in BM from healthy donors; a representative of 5 samples is shown. Using a strategy similar to that described for PB, all 4 cell types were found to be CD38hiCD27hi. (D) Histograms showing cell size and expression levels of CD19, cytoplasmic Ig LC, CD319, CD20, and HLA-DR of BM B lineage populations.

CD19−CD138− Pre-PCs are a feature of the normal late B-cell development. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of the normal late B-cell development in PB (n = 15 normal donors); a representative donor sample is shown. After gating out non–B-cell lineage cells, analysis of CD19+ cells, as expected, shows a polyclonal pattern of cytoplasmic Ig LC expression (ie, expression of κ and λ chains). PBLs are identified as CD38hiCD27hiCD138− and PCs as CD38hiCD27hiCD138+ cells. For identification of Pre-PCs, gating on lineage-CD19− cells reveals a small cytoplasmic Ig LC+ population, which on sequential gating is found to be enriched in CD38hiCD27hi cells (48% in the case shown); these include CD138+ PCs and CD138− Pre-PCs. Both CD19+ PBLs/PCs and CD19− Pre-PCs/PCs are CD319+. (B) Histograms showing cell size as assessed by FSC-A and expression levels of CD19, cytoplasmic Ig LC, CD319, CD20, and HLA-DR in the above 4 populations as well as in naive and memory B cells. Numbers next to histograms represent median intensity fluorescence values. (C) Identification of PBLs, CD19+ PCs, Pre-PCs, and CD19− PCs in BM from healthy donors; a representative of 5 samples is shown. Using a strategy similar to that described for PB, all 4 cell types were found to be CD38hiCD27hi. (D) Histograms showing cell size and expression levels of CD19, cytoplasmic Ig LC, CD319, CD20, and HLA-DR of BM B lineage populations.

To further investigate the phenotypic relationship of the myeloma clonotypic architecture with that of the normal late B-cell differentiation program, we applied a similar immunophenotypic strategy in normal BM samples.

In line with previous work,6,27 we found that PCs in normal BM are CD38hiCD27hiCD138+ cells that may or may not express CD19, whereas PBLs are identified as CD19+CD38hiCD27hiCD138− cells (Figure 2C). In addition, in all 5 BM samples tested, we identified a novel CD19−CD27hiCD38hiCD138− population that by immunophenotypic criteria corresponds to myeloma Pre-PCs (Figure 2C). All 4 populations, PBLs, Pre-PCs, and CD19+ or CD19− PCs, compared with memory and naive B cells, displayed strong expression of surface CD319 and cytoplasmic Ig LCs (Figure 2D). Interestingly, both BM and PB Pre-PCs, as assessed by forward scatter criteria, are smaller than PCs (Figure 2B,D). Therefore, PB and BM Pre-PCs are a feature of normal late B-cell architecture as well as of myeloma.

Taken together, these data suggest that clonotypic cells in myeloma are organized in a hierarchy that mirrors, at least in part, that of normal late B-cell development.

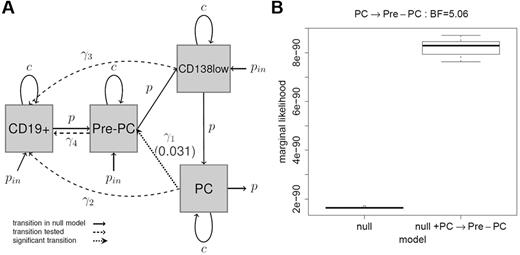

Mathematical modeling of growth and differentiation of myeloma clonotypic cells

Having delineated its phenotypic complexity, we tested directions of phenotypic transitions within the myeloma BM hierarchy by developing dynamic mathematical models (supplemental Methods; supplemental Tables 2-3) and fitting them to the observed frequencies of CD19+ cells, Pre-PCs, CD138low PCs, and CD138+ PCs using maximum likelihood.28 Our null model assumed a linear transition from CD19+ cells to PC via Pre-PC and CD138low cell types. Using the likelihood ratio test, we examined the hypothesis of additional subset transitions. We found that, although each of the Pre-PC → CD19+ cell, CD138lowPC → CD19+ cell, PC → CD19+ cell transitions were not supported in the analysis (P = .999), a PC to Pre-PC transition could be readily identified (P = .031; Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 2). We further investigated the PC to Pre-PC transition by adopting a Bayesian approach and using an MCMC algorithm,29 calculated the marginal likelihood under the null model and the model including the PC to Pre-PC transition (Figure 3B). We obtained a median Bayes factor of 5.06, thus providing strong evidence for the existence of this transition30 suggesting that Pre-PCs and PCs might exist in an interconvertible state.

Modeling analysis of differentiation and proliferation profiles of myeloma clonotypic fractions. (A) Likelihood analysis: the different cell types are represented by the gray squares and transitions between them represented by arrows (with associated rate parameters; see supplemental Methods). The set of black solid arrows indicate the transitions in the null model that assumes linear transition from CD19+ cells to PCs via Pre-PC and CD138low cell types. Each dotted arrow indicates an included transition tested (ie, Pre-PC → CD19+ cell, CD138lowPC → CD19+ cell, PC → CD19+ cell transitions) with respect to the null model using a likelihood ratio test. Black dotted lines indicate transitions that were not significant. The PC to Pre-PC transition (indicated by the dotted line) showed a P value of .031, indicating significance at the 5% level. (B) Bayesian analysis of the PC to Pre-PC transition: to further investigate this transition, an MCMC algorithm was developed to fit a fully Bayesian model. The box plot shows the marginal likelihood for the null model and for the null model, including the PC to Pre-PC transition for 10 runs of the MCMC algorithm with different starting values. The Bayes factor of 5.06, here calculated as the ratio of the marginal likelihoods, represents strong evidence for the inclusion of the PC to Pre-PC transition.

Modeling analysis of differentiation and proliferation profiles of myeloma clonotypic fractions. (A) Likelihood analysis: the different cell types are represented by the gray squares and transitions between them represented by arrows (with associated rate parameters; see supplemental Methods). The set of black solid arrows indicate the transitions in the null model that assumes linear transition from CD19+ cells to PCs via Pre-PC and CD138low cell types. Each dotted arrow indicates an included transition tested (ie, Pre-PC → CD19+ cell, CD138lowPC → CD19+ cell, PC → CD19+ cell transitions) with respect to the null model using a likelihood ratio test. Black dotted lines indicate transitions that were not significant. The PC to Pre-PC transition (indicated by the dotted line) showed a P value of .031, indicating significance at the 5% level. (B) Bayesian analysis of the PC to Pre-PC transition: to further investigate this transition, an MCMC algorithm was developed to fit a fully Bayesian model. The box plot shows the marginal likelihood for the null model and for the null model, including the PC to Pre-PC transition for 10 runs of the MCMC algorithm with different starting values. The Bayes factor of 5.06, here calculated as the ratio of the marginal likelihoods, represents strong evidence for the inclusion of the PC to Pre-PC transition.

Tumor-propagating activity of myeloma clonotypic subsets

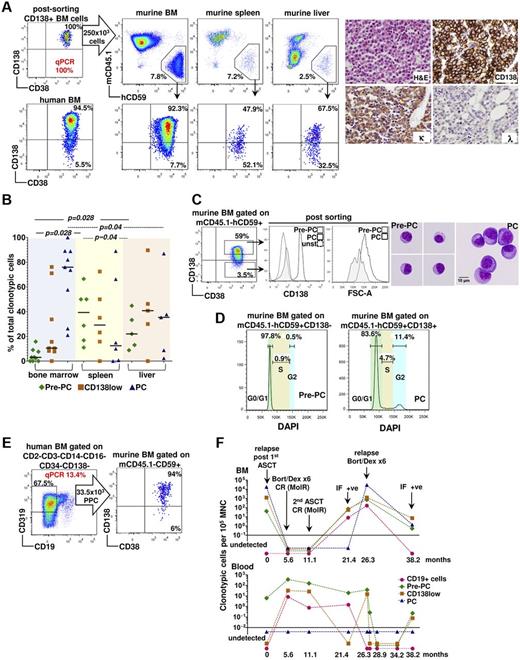

To directly test the predictions of the modeling analysis and the functional relationship of the clonotypic fractions in vivo, we adoptively transferred either highly purified CD19+ cells (ie, a mixture of resting memory B cells and PBL), PCs or Pre-PCs from 8 MM patients into sublethally irradiated NSG mice and followed their engraftment for up to 34 weeks (supplemental Table 4).

As assessed by flow cytometry combined with clonotypic quantitative PCR and immunohistochemistry, mice transplanted with highly purified CD138hi PCs displayed BM engraftment in 75% (9 of 12) of cases (Figure 4A; supplemental Table 4), showing that, contrary to recent data,11-13 CD138+ PCs can engraft immunodeficient mice and therefore are myeloma-propagating, a finding supported by their ability to engraft in secondary transplants (supplemental Figure 3; supplemental Table 4). It should be noted that the observed frequency and level of engraftment in NSG mice were comparable with those previously reported for SCID and NOD/SCID mice31-33 but rather lower than the SCID models involving skin implants of either human or rabbit bone.15,16

Myeloma-propagating potential of Pre-PCs and PCs and partial recapitulation of the clonotypic hierarchy in NSG mice. (A) Left: Highly purified BM CD138hi myeloma PCs transferred to NSG mice engraft murine BM, spleen, and liver. Human cells are identified in mouse tissues by flow cytomtery as hCD59+mCD45.1− (top panels). Engrafted PCs recapitulate the CD19− hierarchy of the human BM (bottom panels); however, in the spleen and liver, there is preferential presence of Pre-PCs and CD138low cells. Right: BM hematoxylin and eosin staining in a mouse transplanted with CD138hi PC shows myeloma cell infiltration. Immunohistochemistry (original magnification ×400) for human κ/λ light chains and CD138 is also shown. In this example, myeloma PCs are κ LC restricted and, as expected, express CD138. (B) Cumulative data of the frequencies of PCs, CD138low, and Pre-PCs in the BM, spleen, and liver in mice receiving patient CD138hi PCs. Horizontal lines indicate median values. (C) Size of BM PCs and Pre-PCs highly purified by flow sorting from the BM of mice engrafted after transfer of CD138hi myeloma PCs. A representative example is shown. (D) Cell cycle analysis in multiparameter flow cytometry of engrafted BM Pre-PCs and PCs. (E) Engraftment pattern in the murine BM after transfer of Pre-PCs recapitulates Pre-PC–PC duality. Pre-PCs were negatively selected by flow sorting as Lin−CD19−CD34−CD138− cells. In this example, 13.4% of the flow-sorted cells were clonotypic as assessed by quantitative PCR and a total of 33.5 × 103 clonotypic B cells were infused. (F) PB and BM clonotypic cell dynamics in the timeline of treatment of a patient with MM (ASCT indicates autologous stem cell transplantation; and Bort/Dex: bortezomib and dexamethasone) and disease status changes (MolR indicaets molecular remission; IF, immunofixation; and CR, complete clinical remission). Blood clonotypic CD19+ cells, Pre-PCs, and CD138low cells, but not PCs, are identified while the patient was in complete clinical and molecular remission in the BM at 5.6 and 11.1 months.

Myeloma-propagating potential of Pre-PCs and PCs and partial recapitulation of the clonotypic hierarchy in NSG mice. (A) Left: Highly purified BM CD138hi myeloma PCs transferred to NSG mice engraft murine BM, spleen, and liver. Human cells are identified in mouse tissues by flow cytomtery as hCD59+mCD45.1− (top panels). Engrafted PCs recapitulate the CD19− hierarchy of the human BM (bottom panels); however, in the spleen and liver, there is preferential presence of Pre-PCs and CD138low cells. Right: BM hematoxylin and eosin staining in a mouse transplanted with CD138hi PC shows myeloma cell infiltration. Immunohistochemistry (original magnification ×400) for human κ/λ light chains and CD138 is also shown. In this example, myeloma PCs are κ LC restricted and, as expected, express CD138. (B) Cumulative data of the frequencies of PCs, CD138low, and Pre-PCs in the BM, spleen, and liver in mice receiving patient CD138hi PCs. Horizontal lines indicate median values. (C) Size of BM PCs and Pre-PCs highly purified by flow sorting from the BM of mice engrafted after transfer of CD138hi myeloma PCs. A representative example is shown. (D) Cell cycle analysis in multiparameter flow cytometry of engrafted BM Pre-PCs and PCs. (E) Engraftment pattern in the murine BM after transfer of Pre-PCs recapitulates Pre-PC–PC duality. Pre-PCs were negatively selected by flow sorting as Lin−CD19−CD34−CD138− cells. In this example, 13.4% of the flow-sorted cells were clonotypic as assessed by quantitative PCR and a total of 33.5 × 103 clonotypic B cells were infused. (F) PB and BM clonotypic cell dynamics in the timeline of treatment of a patient with MM (ASCT indicates autologous stem cell transplantation; and Bort/Dex: bortezomib and dexamethasone) and disease status changes (MolR indicaets molecular remission; IF, immunofixation; and CR, complete clinical remission). Blood clonotypic CD19+ cells, Pre-PCs, and CD138low cells, but not PCs, are identified while the patient was in complete clinical and molecular remission in the BM at 5.6 and 11.1 months.

In line with the modeling analysis prediction of a PC to Pre-PC transition, both Pre-PCs and CD138+/low PCs were identified in BM of mice receiving CD138hi PCs, at frequencies similar to those found in patients' corresponding BM samples (Figure 4A-B). Engrafted PCs and Pre-PCs had the same distinct morphologic (Figure 4C) and cell cycle status features (Figure 4D) as in the patient BM (Figure 6D); that is, Pre-PCs were smaller and more quiescent cells, thus recapitulating the original, clonotypic Pre-PC–CD138low–PC hierarchy observed in the patient BM. However, as also predicted by the modeling analysis, CD19+ human cells were never detected (data not shown) in the BM of these mice.

We also found clonotypic cells in the spleen and liver of mice transplanted with CD138hi PCs, although at an overall lower frequency than in BM (supplemental Table 4). Notably, unlike the BM where CD138+ PCs composed the majority of clonotypic cells, the spleen and liver contained predominantly Pre-PC and CD138low myeloma cells rather than CD138+ PCs (Figure 4A-B). These data support the important role played by the microenvironment in modulating the behavior of MM clonotypic cells and suggest that preferential microenvironmental localization as well as phenotypic differences distinguish Pre-PCs from PCs.

To formally test in vivo the Pre-PC to PC transition, negatively enriched (to avoid anti-CD38 mAb-mediated cell opsonization21 ) Pre-PCs were transferred into NSG mice. Despite a lower engraftment rate (25%, 4 of 16 mice; supplemental Table 4), which probably reflects the lower numbers of cells available compared with PCs, the pattern of CD138 expression in BM was similar to that generated by CD138hi PCs (ie, predominance of CD138+ PCs over Pre-PCs; Figure 4E). Finally, as previously reported,15,16 none of the mice (0 of 10) transplanted with CD19+ cells showed evidence of engraftment (supplemental Figure 4), supporting lack of myeloma-propagating activity in CD19+ clonotypic cells.

Together, these data indicate that, within the myeloma phenotypic hierarchy, myeloma-propagating activity is the exclusive property of a population which can assume 2 interconvertible phenotypic states distinguished by their expression of CD138. Interestingly, the preferential localization of cells with low or no expression of CD138 in the liver and spleen of engrafted animals, and their preferential presence in PB of patients, suggests the existence of extramedullary sites of MM localization. In line with this notion in humans, prospective analysis of several paired BM-PB samples in patient P12 (supplemental Table 1) over a period of 38 months showed in 2 consecutive time points the presence of circulating Pre-PC and clonotypic CD19+ cells while the patient was in complete clinical remission18 and in molecular remission in the BM (Figure 4F).

Global mRNA expression profiling of Pre-PCs and PCs

To gain insights into the molecular mechanisms underpinning the reversible, bidirectional Pre-PC to PC transition, we subjected highly purified (> 99%) Pre-PC to PC pairs from 9 patients (supplemental Table 5) to global mRNA expression profiling. Hierarchical clustering of the 1000 genes with the highest fold change in mRNA expression between the 2 cell types revealed distinct clusters of gene expression separating PCs from Pre-PCs in 7 samples, whereas the other 2 samples formed a different distinct pattern (Figure 5A). Further analysis focused on the 7 samples sharing the same hierarchical clustering pattern (Figure 5B), identifying 1509 differentially expressed genes at P < .05. A principal component analysis of these genes showed clear separation of PCs and Pre-PCs along the first principal component in all 7 pairs (P = 4 × 10−6; Figure 5C; supplemental Figure 4). To reduce our gene set for pathway analysis and enrich for those genes involved in separating PCs and Pre-PCs, a threshold on the loading of the first principal component was applied resulting in 1094 genes.

Global mRNA profile analysis of Pre-PCs and PCs. (A) Hierarchical clustering of all 9 Pre-PC and PC pairs. (B) Hierarchical clustering of the 1000 more differentially expressed genes in 7 pairs of Pre-PCs and PCs. (C) Principal component analysis on 1509 differentially expressed genes (P < .05) in which PCs and Pre-PCs were clearly separated along the first principal component in all 7 pairs. (D) Pathway analysis of genes involved in separating PCs and Pre-PCs. The 3 top scoring gene clusters are enriched in Pre-PCs and contain genes involved in chromatin modification, chromatin organization, and chromosome organization. P values represent a Benjamini-Hochberg corrected modified Fisher exact test.

Global mRNA profile analysis of Pre-PCs and PCs. (A) Hierarchical clustering of all 9 Pre-PC and PC pairs. (B) Hierarchical clustering of the 1000 more differentially expressed genes in 7 pairs of Pre-PCs and PCs. (C) Principal component analysis on 1509 differentially expressed genes (P < .05) in which PCs and Pre-PCs were clearly separated along the first principal component in all 7 pairs. (D) Pathway analysis of genes involved in separating PCs and Pre-PCs. The 3 top scoring gene clusters are enriched in Pre-PCs and contain genes involved in chromatin modification, chromatin organization, and chromosome organization. P values represent a Benjamini-Hochberg corrected modified Fisher exact test.

On functional annotation clustering using DAVID (supplemental Table 6), a graph-based annotation clustering algorithm,34 the highest scoring cluster contained these GO terms plus the UniProtKB chromatin regulator term. The list of genes in this cluster contained several chromatin regulators, including histone methyl-transferases (belonging to the Polycomb repressive complex 2 or Trithorax MLL activating complex) and demethylases, histone acetyltransferases, and deacetylases as well as several members of SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex (supplemental Table 7).

Taken together, these findings suggest an important role of “epigenetic plasticity” determining the process of bidirectional transition of myeloma-propagating cells.

Pre-PCs and clinical drug resistance

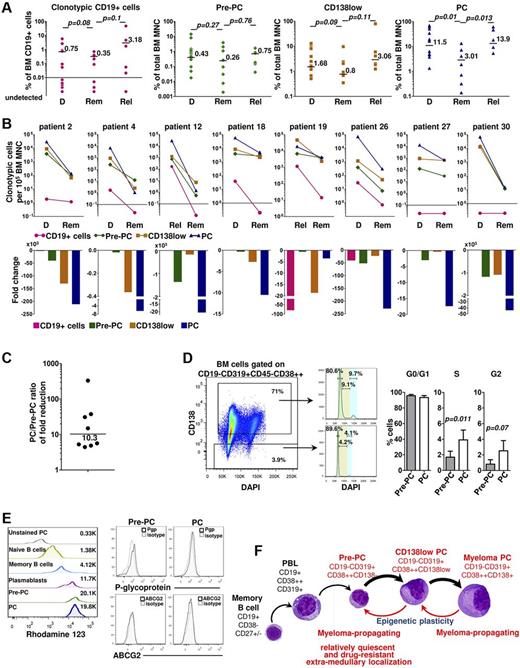

Because reduction or loss of CD138 expression was previously associated with increased chemoresistance of a myeloma cell line in vitro,35 we addressed whether Pre-PC to PC transition is linked to differential treatment responses in primary MM cells in vivo. For this purpose, we first compared the frequency of clonotypic CD19+ cells, Pre-PCs, and PCs in patients at diagnosis with those in remission after treatment that included chemotherapy, the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (supplemental Table 1). As expected, the PC frequency in the BM from diagnosis to remission was significantly lower (P = .013; Figure 6A). However, consistent with clinical drug resistance, the frequency of BM CD19+ clonotypic cells and Pre-PCs remained unchanged (P > .05; Figure 6A).

Drug-resistance and quiescence of Pre-PCs in vivo. (A) Frequencies of BM clonotypic cells at diagnosis (D), remission (Rem), and relapse (Rel). (B) Frequency (top panels) and fold change (bottom panels) of clonotypic fractions in 8 patients achieving clinical remission after treatment. Top panels: Absolute frequency changes in the clonotypic fractions. Bottom panel: Relative changes in the frequency of the clonotypic cells. (C) The ratio of PC/Pre-PC fold reduction (median, 10.3; range, 4.4-332; P = .008) as estimated in each patient from panel C. (D) Cell cycle analysis after DAPI staining and multiparameter flow cytometry of BM cells shows that a significantly lower fraction of Pre-PCs than PCs are in S phase. An example and cumulative data from 7 patients are shown. (E) Left: Flow cytometry histograms showing rhodamine 123 dye exclusion by myeloma Pre-PCs and PCs compared with PBLs, naive, and memory B cells. Unstained PCs are shown as a negative control. PCs and Pre-PCs retain comparable levels of rhodamine 123 as assessed by MFI. Right: P-glycoprotein (ABCC1) and ABCG2 are not expressed in Pre-PCs or PCs as assessed by flow cytometry in BM samples. Representative of 10 patient samples. (F) A model of clonotypic hierarchy and myeloma-propagating activity. Memory B cells are at the apex of the clonotypic hierarchy in MM. However, myeloma-propagating activity is detected in the terminally differentiated B lineage cell that through an epigenetic, bidirectional transition can assume the morphologically and immunophenotypically distinct states of Pre-PCs and PCs. In most patients, the equilibrium of Pre-PC to PC transition favors PCs. Although both are enriched in myeloma-propagating activity, Pre-PCs are relatively more quiescent and treatment-resistant than PCs and in vivo are preferentially present in spleen and liver, whereas PCs are the dominant population in BM.

Drug-resistance and quiescence of Pre-PCs in vivo. (A) Frequencies of BM clonotypic cells at diagnosis (D), remission (Rem), and relapse (Rel). (B) Frequency (top panels) and fold change (bottom panels) of clonotypic fractions in 8 patients achieving clinical remission after treatment. Top panels: Absolute frequency changes in the clonotypic fractions. Bottom panel: Relative changes in the frequency of the clonotypic cells. (C) The ratio of PC/Pre-PC fold reduction (median, 10.3; range, 4.4-332; P = .008) as estimated in each patient from panel C. (D) Cell cycle analysis after DAPI staining and multiparameter flow cytometry of BM cells shows that a significantly lower fraction of Pre-PCs than PCs are in S phase. An example and cumulative data from 7 patients are shown. (E) Left: Flow cytometry histograms showing rhodamine 123 dye exclusion by myeloma Pre-PCs and PCs compared with PBLs, naive, and memory B cells. Unstained PCs are shown as a negative control. PCs and Pre-PCs retain comparable levels of rhodamine 123 as assessed by MFI. Right: P-glycoprotein (ABCC1) and ABCG2 are not expressed in Pre-PCs or PCs as assessed by flow cytometry in BM samples. Representative of 10 patient samples. (F) A model of clonotypic hierarchy and myeloma-propagating activity. Memory B cells are at the apex of the clonotypic hierarchy in MM. However, myeloma-propagating activity is detected in the terminally differentiated B lineage cell that through an epigenetic, bidirectional transition can assume the morphologically and immunophenotypically distinct states of Pre-PCs and PCs. In most patients, the equilibrium of Pre-PC to PC transition favors PCs. Although both are enriched in myeloma-propagating activity, Pre-PCs are relatively more quiescent and treatment-resistant than PCs and in vivo are preferentially present in spleen and liver, whereas PCs are the dominant population in BM.

To further investigate the resistance of Pre-PCs to treatment, we carried out a prospective quantitative assessment of BM clonotypic cells in paired pretreatment and posttreatment clinical remission samples from 8 MM patients. Consistent with clinical drug resistance, in all 8 patients, a significantly higher proportion of Pre-PCs than PCs persisted after treatment, with an overall 10.3-fold smaller reduction (range, 4.4-332; P = .008) in the frequency of Pre-PCs compared with PCs (Figure 6B-C). Although Pre-PCs were more quiescent than PCs as revealed by the significantly (P = .01) lower proportion of Pre-PCs in S phase of the cell cycle (Figure 6D), a property also consistent with drug resistance, both Pre-PCs and PCs excluded vital dye equally efficiently and lacked surface expression of the drug efflux proteins ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein) and ABCG236 (Figure 6E), suggesting that their differential response to treatment does not involve a drug efflux-mediated process commonly implicated in tumor chemo resistance.

Taken together, these data show that both PC and Pre-PC fractions harbor myeloma-propagating activity and represent 2 dynamic and interconvertible states of the same clonal population displaying differential response to treatment and preference for anatomic sites.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated myeloma-propagating activity based on the most comprehensive dissection of the phenotypic diversity in myeloma to date. Whereas previous studies suggested the presence of CD19+CD138− clonotypic cells as well as the dominant CD19−CD138+ PCs, we show that the myeloma cellular architecture is composed of at least 4 distinct populations. The data that emerged from the large cohort of MM patients we studied strongly suggests a hierarchical arrangement of these populations, mirroring that of normal B cells (ie, with clonotypic memory B cells followed by CD19+ PBLs at the apex of the hierarchy and the CD19−CD138+ PCs as the most mature cellular population). The CD19−CD38hiCD319+CD138− immunophenotype of Pre-PCs, a population only incompletely studied in myeloma, suggested that within this hierarchy, Pre-PCs are placed between PBLs and PCs. This is further supported by (1) high expression in Pre-PC of CD319, a SLAM family receptor highly expressed in normal and malignant PCs37 ; (2) identification both in BM and PB of normal persons of a population with exactly the same phenotype as myeloma Pre-PCs (ie, CD19−CD38hiCD319+CD138− cells); and (3) the ability of Pre-PCs to generate PCs but not PBLs in the xenograft assays.

As shown in Figure 2 and previously reported,27 PBLs, that is, CD38hiCD27hiCD319+CD138− cells that express CD19 compose a sizeable fraction of normal late B-cell development. PBLs are considered to represent differentiating, Ig-secreting cells migrating from secondary lymphoid organs to the BM where they complete their maturation to CD38hiCD27hiCD319+CD138+ PCs,6 with the majority of normal BM PCs retaining expression of CD19. However, in myeloma, clonotypic CD19+ PBL-like cells are infrequently identified (data not shown). By contrast, as previously reported,38 the dominant myeloma PCs were CD19− in all cases, suggesting a specific propensity of CD19− but not of CD19+ late B-cell lineage cells to myelomatous transformation.

In principle, Pre-PC in myeloma could be generated through forward differentiation of clonotypic CD19+ B cells or by reverse differentiation of mature CD138+ PCs. The detailed and precise phenotypic and molecular data accrued from 30 patients allowed the development of a mathematical model that was constructed assuming a forward CD19+ → Pre-PC → CD138low → PC differentiation potential and was used to ask whether reverse differentiation programs were possible. It clearly showed that only a PC to Pre-PC transition was possible, suggesting a distinct role of Pre-PC to PC bidirectional transition in the biology of myeloma. Xenograft assays, as well as confirming this prediction, they also showed that Pre-PC to PC bidirectional transition is a phenomenon observed irrespective of the primary oncogenic genetic events or clinical stage of disease (supplemental Tables 1 and 4).

Unlike myeloma PCs and Pre-PCs, clonotypic primary CD19+ B cells (ie, memory B cells and PBLs) failed to engraft. This may reflect either insufficient numbers of clonotypic cells injected (ie, a 5-fold smaller dose of Pre-PCs than PCs were transferred into NSG mice; supplemental Table 4), dependence of these cells on external cues that are not provided by the microenvironment in NSG mice or lack of myeloma-propagating activity of CD19+ clonotypic cells as previously reported.15 Use of a larger numbers of clonotypic B cells and their transfer into a new generation of humanized mice, such as the HLA-DR–expressing NSG mice,39 would be required to definitively address the tumor propagating potential of clonotypic B cells in myeloma.

Taken together, our in vivo experiments clearly demonstrated that the myeloma-propagating activity is a property shared by both CD19−CD138− Pre-PCs and CD19−CD138+ PCs, but it does not appear to include CD19+CD138− clonotypic B cells, thus resolving the current uncertainty whether CD138+ versus CD138− cells are enriched in tumor-propagating activity.1 In addition, our findings support recent data showing that the myeloma side population, highly enriched in myeloma-propagating activity, includes both CD138+ and CD138− cells.17

Pre-PCs not only resemble small lymphocytes and are more quiescent than PCs, they are also molecularly distinct to PCs as shown by mRNA expression profiling and principal component analysis. The molecular signature of Pre-PCs is composed of epigenetic regulators enriched in components of the Polycomb-repressive complex, MLL transcriptional activating complex, and the chromatin remodeler SWI/SNF, consistent with epigenetic plasticity controlling the bidirectional Pre-PC to PC transition (Figure 6F).

Nongenetic, including epigenetic, clonal diversification has previously been predicted on theoretical grounds40,41 and experimentally addressed in multipotent hematopoietic progenitor42 and cancer cell lines43 in vitro. The same process was shown to underlie the transient and reversible drug-tolerant states of a small minority of cells (termed drug-tolerant persisters) in a variety of human cell lines in vitro.43 Our finding that the low-frequency, phenotypically and molecularly distinct Pre-PCs are significantly less sensitive to antimyeloma treatment than PCs provides strong support for the importance of nongenetic mechanisms in instructing clinical drug resistance also in vivo in primary tumors; the lack of a drug efflux mechanism associated with clinical drug resistance in myeloma is another feature that Pre-PCs share with drug-tolerant persisters.43 Nevertheless, it is likely, if not certain, that irreversible genetic, mutational mechanisms would eventually also instruct myeloma-propagating activity as well as drug resistance. Indeed, it is predicted40,41 that nonmutational diversification may promote and cooperate with mutational mechanisms leading to clonal evolution. Finally, it should be noted that CD138 mRNA was not differentially expressed between Pre-PCs and PCs (data not shown), suggesting that its down-regulation in Pre-PCs is mediated primarily through post-transcriptional mechanisms, probably by its cleavage at the cell surface.44 Whether down-regulation of CD138 expression in itself is necessary or it is just a marker for the Pre-PC to PC transition remains to be determined.

The observation that the PC–Pre-PC equilibrium is subject to microenvironmental constraints, with the CD138+ status predominant in BM and the CD138− status predominant in the spleen, liver, and possibly other anatomic sites of the engrafted animals, provides another example of the close relationship between myeloma and microenvironment. Consistent with previous observations in tumor models showing the ability of the microenvironment to impart de novo drug resistance and shape phenotypic diversity of tumor cells through nongenetic mechanisms,45 the data presented here suggest that extramedullary locations function as sanctuaries of drug resistance and relapse in myeloma. This is further highlighted by (1) patient P12 in whom Pre-PCs but not PCs persisted in PB despite complete clinical and molecular remission in the BM in 2 consecutive time points in the course of the disease and (2) the clinical observation that in up to 35% of patients with MM, after high-dose chemoradiotherapy and autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation, relapse can take place in extramedullary sites without evidence of concurrent BM disease.46,47

From a clinical perspective, our findings suggest that current methods of assessing minimal residual disease relying on the identification of CD138+ cells in the BM38 should be reevaluated to include CD138− clonotypic cells in blood as well as BM. Moreover, use of mAb for therapeutic targeting of CD13848 might favor survival of inherently drug-resistant, myeloma-propagating cells, and current and future therapeutic strategies should aim at effectively targeting all clonotypic myeloma fractions. Finally, delineation of the precise role of the epigenetic regulators, such as Polycomb and MLL in the Pre-PC to PC transition, will offer opportunities for development of novel epigenetic therapies in MM.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Leukemia and Lymphoma Research, Leuka, and the National Institute of Health Research Biomedical Research Center.

Authorship

Contribution: A.C. designed and performed research, analyzed data, wrote the paper; C.P.B. performed mathematical modeling, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; H.H. and M.S. performed mathematical modeling and analyzed data; G.C., P.C.M., V.M., A. Reid, and H.D. performed, researched, and analyzed data; E.H., M.P., E.T., M.D., S.A., H.Y., and A. Rahemtulla contributed patient samples and information and contributed to manuscript writing; K.N. and L.F. supervised part of research and analyzed data; I.R. analyzed data, contributed to the writing of paper, and supervised research; and A.K. designed and supervised research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anastasios Karadimitris, Centre for Haematology, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London, Hammersmith Hospital, Du Cane Road, London W12 0NN, United Kingdom; e-mail: a.karadimitris@imperial.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal