Abstract

Survival in severe aplastic anemia (SAA) has markedly improved in the past 4 decades because of advances in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, immunosuppressive biologics and drugs, and supportive care. However, management of SAA patients remains challenging, both acutely in addressing the immediate consequences of pancytopenia and in the long term because of the disease's natural history and the consequences of therapy. Recent insights into pathophysiology have practical implications. We review key aspects of differential diagnosis, considerations in the choice of first- and second-line therapies, and the management of patients after immunosuppression, based on both a critical review of the recent literature and our large personal and research protocol experience of bone marrow failure in the Hematology Branch of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Introduction

Until the 1970s, severe aplastic anemia (SAA) was almost uniformly fatal, but in the early 21st century most patients can be effectively treated and can expect long-term survival. Nevertheless, making a diagnosis and selecting among treatment options are not straightforward, and both physicians and patients face serious decision points at the outset of their disease to years after its presentation. We summarize our approach to SAA, with recommendations based on decades of experience in the clinic as well as a critical review of the literature. Unfortunately, as a rare disease, there are few large trials of any kind and even fewer randomized controlled studies, which usually provide the best evidence to guide practice in the clinic.

Pathophysiology as basis of diagnosis and treatment

The pathophysiology responsible for marrow cell destruction and peripheral blood pancytopenia has itself been inferred from the results of treatment in humans, with substantial in vitro and animal model support. The reader is referred to more didactic textbook chapters and formal reviews on these topics.1-4 The success of HSCT in restoring hematopoiesis in SAA patients implicated a deficiency of HSCs. Hematologic improvement after immunosuppressive therapy (IST), initially in the context of rejected allogeneic grafts and then in patients receiving only IST, implicated the immune system in destruction of marrow stem and progenitor cells. Immune-mediated marrow failure can be modeled in the mouse by the “runt” version of GVHD, with HSC depletion and hematopoietic failure induced by infusion of lymphocytes mismatched at major or minor histocompatibility loci.5,6

Genetics influences both the immune response and its effects on the hematopoietic compartment. There are histocompatibility gene associations with SAA,7 and some cytokine genes may be more readily activated in patients because of differences in their regulation, as suggested by polymorphisms in promoter regions.8 An inability to repair telomeres and to maintain the marrow's regenerative capacity, resulting from mutations in the complex of genes responsible for telomere elongation, has been linked to patients with familial or apparently acquired SAA, with or without the typical physical stigmata of constitutional aplastic anemia. These genetic factors are variable in their penetrance, ranging from highly determinant loss-of-function mutations to subtle polymorphisms.9

Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with SAA have a preceding seronegative hepatitis.10 However, most patients do not have a history of identifiable chemical, infectious, or medical drug exposure before onset of pancytopenia. The antigen(s) inciting the aberrant immune response have not been identified in SAA. Furthermore, the current simple mechanistic outline may be supplemented in the future with better understanding of now theoretical possibilities, suggested by provocative murine models: an active role of adipocytes in inhibition of hematopoiesis11,12 ; interactions among effector CD8 and CD4 cells5 and regulatory cells,13-15 and possible microenvironment “field effects” by stromal elements and niche cell interactions.16

How we diagnose SAA

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

Patients with SAA usually have been previously well, prior to the diagnosis. For the consultant hematologist, the differential will mainly lie among hematologic syndromes, usually distinguishable on bone marrow examination. The reader is referred to general references for a complete list of diseases that can present with various degrees of cytopenias.4 An elevated mean corpuscular volume is frequent in aplastic anemia at presentation. The “empty” marrow on histology of SAA is highly characteristic and a requisite for the diagnosis. Marked hemophagocytosis, obvious dysplasia, or increased blasts indicate other diseases, although differentiation of hypocellular myelodysplastic syndrome (seen in ∼ 20% of myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS] cases) from aplastic anemia can be difficult. Megakaryocytes are the most reliable lineage to use in distinguishing MDS from SAA: small mononuclear or aberrant megakaryocytes are typical of MDS, whereas megakaryocytes are markedly reduced or absent in SAA. In contrast, “megaloblastoid” and modest dysplastic erythropoiesis are not uncommon in an aplastic marrow, especially when a paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) clone is present. Cytogenetics are helpful when typical of MDS, but some aberrations (such as trisomy 6, trisomy 8, and 13q−) may appear in SAA that is responsive to IST, according to some reports,17,18 but not confirmed by others19 (for our SAA research protocols, abnormal chromosomes are an exclusion criterion).

Aplastic anemia and PNH overlap in approximately 40% to 50% of cases (the AA/PNH syndrome).20 At our institution, more than 1% granulocytes deficient in glycosylphosphoinsoitol-linked proteins detectable by flow cytometry are considered abnormal, but other methodologies can detect even smaller PNH clones. Such small clones do not result in significant hemolysis or risk of thrombosis, and whether the presence of a small PNH clone in the setting of hypocellular marrow failure has clinical significance or predicts response to treatment and outcomes is controversial.21,22 The presence of less than 50% glycosylphosphatidylinositol-deficient circulating cells without evidence for thrombosis or significant hemolysis generally does not require PNH-specific therapy.20 Irrespective of PNH clone size, marrow failure in SAA should be treated promptly with immunosuppression or transplantation because complications of pancytopenia represent the more imminent cause of morbidity and mortality.

The appearance of the marrow in inherited and acquired aplastic anemia syndromes is identical, and the historical distinction between them is becoming blurred. Fanconi anemia is established by testing peripheral blood for increased chromosomal breakage after exposure to diepoxybutane or other clastogenic stress. What is the upper age limit for performing this assay in patients who present with marrow failure, as Fanconi anemia manifestations can first appear in adulthood? We use age 40 years as a threshold but may perform testing on older patients if the family history is even minimally suggestive of inherited marrow failure, or there are potential consequences for an error in diagnosis as, for example, exposure to chemotherapy. The diagnosis of Fanconi anemia is critical, because these patients do not respond to IST, require dose-reductions in transplant conditioning, and need careful follow-up for a range of nonhematologic malignancies.

The diagnosis and implications of documenting telomeropathies in patients with marrow failure are problematic because of the range of clinical phenotypes: from classic X-linked dyskeratosis congenita kindreds with hemizygous DKC1 mutations, in which boys present early in life with pancytopenia and typical physical features (abnormal nails, leukoplakia, cutaneous eruptions), to older adults with heterozygous TERT or TERC mutations, in whom the family history can be negative or obscure and who lack pathognomonic physical findings. Blood leukocyte telomere length measurement is probably appropriate in all aplastic anemia patients but especially important in those who have a family history of aplastic anemia, isolated cytopenias, and leukemia, as well as pulmonary fibrosis or cirrhosis.9 We do not label such patients as dyskeratosis congenita (the most severe type linked to DKC1 mutations) but rather as telomere disease or telomeropathy because the penetrance of the TERT and TERC gene mutations is much lower and the long-term clinical outcomes currently less clear but the focus of current investigations. Current clinical research protocols at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are investigating the impact of telomere length and mutational status on aplastic anemia outcomes and the effects of androgens on modulating telomere attrition.

Presentation and patterns

It is common for SAA patients to seek medical attention because of symptoms of anemia or hemorrhage. Infection at presentation is infrequent, even with severe neutropenia. Pancytopenia can be discovered serendipitously at preoperative evaluation, blood donation, or from screening testing. Curiously, there may be a prior history of a single lineage cytopenia, usually thrombocytopenia or anemia. For aplastic anemia patients who present with thrombocytopenia alone, standard therapies for immune thrombocytopenia are usually ineffective, and eventually a diagnosis of marrow failure follows from the finding of a hypocellular marrow with reduced megakaryocytes. Macrocytosis and even mild anemia (or leucopenia) should suggest that ITP is not the correct diagnosis and stimulate an early marrow biopsy. Months of unsuccessful treatment with corticosteroids in these patients is to be avoided. A prior history of seronegative hepatitis in the months before pancytopenia defines posthepatitis SAA. Chemical and medical drug exposures should be queried in the interview, but these are notoriously difficult to evaluate quantitatively and the history is subject to recall bias. However, even with an exhaustive attempt to identify a putative trigger, confirmation of a causal relationship is difficult and the management and outcomes not likely to differ from idiopathic disease.23-26 More important is a careful past medical history of earlier blood count abnormalities, macrocytosis, or relevant pulmonary or liver diseases in the patient or the patient's family, frequent in telomere disorders.

When a medical drug exposure is suspected, some physicians will monitor after its discontinuation; usually, by the time the patient has reached a tertiary care facility, some weeks of data can be assessed for any evidence of marrow recovery. However, the demographics, presenting symptoms, blood counts, and marrow histology, are not different between idiopathic and drug-associated aplastic anemia, and prolonged delay until initiation of primary treatment, in the hope of “spontaneous recovery,” is not generally desirable and can result in serious complications before definitive therapy.

How we treat SAA

When and whom to treat

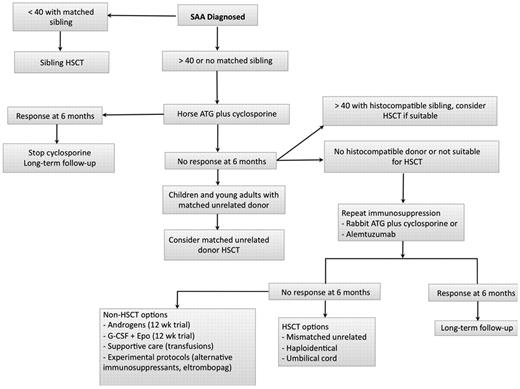

SAA almost always requires treatment, both immediate and definitive. For patients with moderate aplastic anemia, as defined by lack of blood count criteria for SAA, observation is often appropriate, especially when they do not require transfusion support. In our experience, many of these patients may have stable blood counts for years, but in some pancytopenia worsens over time.27 Those who progress to severe pancytopenia and meet the criteria for SAA or become transfusion-dependent can then be treated according to current algorithms (Figure 1), as detailed below. Elderly, feeble, or patients with serious comorbidities may not benefit from more aggressive approaches described in “Transplantation” and “Immunosuppressive therapy,” especially if they are not bleeding and have neutrophil counts that protect from serious infections (generally > 200-400/μL). They may be stable and maintain quality of life with regular red blood cell transfusion; however, age itself does not preclude IST.

Algorithm for initial management of SAA. In patients who are not candidates for a matched related HSCT, immunosuppression with horse ATG plus cyclosporine should be the initial therapy. We assess for response at 3 and 6 months but usually wait 6 months before deciding on further interventions in case of nonresponders. In patients who are doing poorly clinically with persistent neutrophil count less than 200/μL, we proceed to salvage therapies earlier between 3 and 6 months. Transplant options are reassessed at 6 months, and donor availability, age, comorbidities, and neutrophil count become important considerations. We favor a matched unrelated HSCT in younger patients with a histocompatible donor and repeat immunosuppression for all other patients. In patients with a persistently low neutrophil count in the very severe range, we may consider a matched unrelated donor HSCT in older patients. In patients who remain refractory after 2 cycles of immunosuppression, further management is then individualized taking into consideration suitability for a higher risk HSCT (mismatched unrelated, haploidentical, or umbilical cord donor), age, comorbidities, neutrophil count, and overall clinical status. Some authorities in SAA consider 50 years of age as the cut-off for sibling HSCT as first-line therapy.

Algorithm for initial management of SAA. In patients who are not candidates for a matched related HSCT, immunosuppression with horse ATG plus cyclosporine should be the initial therapy. We assess for response at 3 and 6 months but usually wait 6 months before deciding on further interventions in case of nonresponders. In patients who are doing poorly clinically with persistent neutrophil count less than 200/μL, we proceed to salvage therapies earlier between 3 and 6 months. Transplant options are reassessed at 6 months, and donor availability, age, comorbidities, and neutrophil count become important considerations. We favor a matched unrelated HSCT in younger patients with a histocompatible donor and repeat immunosuppression for all other patients. In patients with a persistently low neutrophil count in the very severe range, we may consider a matched unrelated donor HSCT in older patients. In patients who remain refractory after 2 cycles of immunosuppression, further management is then individualized taking into consideration suitability for a higher risk HSCT (mismatched unrelated, haploidentical, or umbilical cord donor), age, comorbidities, neutrophil count, and overall clinical status. Some authorities in SAA consider 50 years of age as the cut-off for sibling HSCT as first-line therapy.

Immediate measures

Symptoms related to anemia and thrombocytopenia can be readily corrected with transfusions. Broad spectrum parenteral antibiotics are indicated when fever or documented infection occurs in the presence of severe neutropenia (< 500/μL). Overuse of blood products should be avoided, but so also should inadequate transfusions; modern preparations of red cells and platelets are not likely to jeopardize graft acceptance at transplant, and they lead to alloimmunization in only a small number of patients. We do not transfuse platelets prophylactically in SAA patients who have a platelet count more than 10 000/μL and who are not bleeding. It is also prudent to rapidly assess whether matched sibling donors exist in the family for any patients younger than 40 years of age (see “How we treat SAA”).

What not to do

Supportive measures alone, growth factors, androgens, or cyclosporine (CsA) are not definitive therapies. Patients should not be subject to initial trials of G-CSF or erythropoietin.28 Corticosteroids are of unproven benefit and inferior in efficacy to conventional immunosuppression regimens, but they are more toxic and should not be used as therapy in SAA. It is very unfortunate when a patient with SAA presents for transplant or IST but already has a life-threatening fungal infection because of weeks or months of exposure to corticosteroids. Watchful waiting, especially if neutropenia is profound, can be harmful and is not appropriate once a diagnosis of SAA is confirmed. If by the time the patient is referred to a hematologist after several weeks and the diagnosis confirmed, spontaneous recovery should be considered unlikely. Aplastic anemia is an unusual disease, and the practicing hematologist/oncologist should feel no hesitation in rapidly referring a patient to a specialized center or in seeking the advice of experts familiar with marrow failure syndromes.

Choice of definitive treatment

Hematopoiesis can be restored in SAA with HSCT or IST. Whereas overall long-term survival is comparable with either treatment modality, transplantation is preferred when feasible as it is curative.1 However, most patients are not suitable candidates for optimal initial HSCT because of lack of a matched sibling donor, lead time to identify a suitable unrelated donor, age, comorbidities, or access to transplantation. Therefore, IST is most commonly used as first therapy in the United States and worldwide.

Transplantation

Matched related HSCT.

The large experience with matched sibling HSCT from the 1970s to the 1990s defined its utility in SAA.1,29 The historically high rate of graft rejection in SAA is now less problematic, probably because of patients moving faster to this treatment and thus avoiding heavy transfusion burdens, less immunogenic blood products, and more efficacious conditioning regimens. The correlation of increasing age with the risk of GVHD and the significant morbidity and mortality of this transplant complication continue to impact on the decision to pursue HSCT versus IST as initial therapy in adults with SAA. In recent reporting by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research of more than 1300 SAA patients who were transplanted from 1991 to 2004, survival at 5 years for patients younger than 20 years of age was 82%, for those 20 to 40 years of age 72%, and for those older than 40 years, closer to 50%.30 Rates of GVHD increased with age, accounting for much of the decreased survival in older patients and the long-term morbidity. Thus, outcomes in the most favorable age group (children with matched sibling donor) resulted in long-term survival of approximate 80%.30 In the Seattle experience, most children who received HSCT from a histocompatible sibling with nonirradiation conditioning regimens were able to grow, develop normally, and retain fertility.31 In this pediatric cohort, chronic GVHD associated with increased mortality, a finding similar to that of adult SAA patients.32 In a retrospective report from Seattle, the experience of matched related HSCT as first therapy in 23 older patients (> 40 years old) showed long-term survival of approximately 60%, in accordance with the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research data.33 Matched sibling transplantation is always preferred in children with SAA, and it is an appropriate first choice for adults up through at least age 40, as proposed in several algorithms.34,35 Thus, as the risks associated with transplantation increase in patients older than 40 years, we generally recommend IST first in this age group (Figure 1).35-37

Stem cell source.

In general, mobilized peripheral blood as a source of stem cells for transplantation has supplanted bone marrow because of higher stem cell doses and donor and physician preference because of ease of collection. Distinctively in SAA, peripheral blood stem cell results have been inferior to grafts of bone marrow origin. In a retrospective analysis, the rate of chronic GVHD was greater with peripheral blood (27%) compared with bone marrow stem cell grafts (12%) in patients younger than 20 years.38 In a subsequent retrospective analysis, similar higher rates of chronic GVHD were observed for patients of all ages undergoing HSCT with peripheral blood compared with bone marrow derived stem cell grafts.39 For unrelated donor transplants, bone marrow source of stem cells was associated with lower rates of acute GVHD (31%) compared with peripheral blood-derived CD34+ cells (48%), and better overall survival (76% vs 61%, respectively).40 In contrast to allogeneic transplantation undertaken for malignancies, where GVHD may offer graft-versus-tumor benefits, in SAA GVHD is unequivocally to be avoided, and its occurrence decreases survival and long-term quality of life. Thus, except for experimental clinical research, bone marrow is preferred as the source of stem cells in SAA.

Alternative donor HSCT.

Outcomes with unrelated donor (UD) HSCT have improved (Table 1),41,42 because of more stringent donor selection facilitated by high-resolution molecular typing, less toxic and more effective conditioning regimens, and higher quality transfusion and antimicrobial supportive care.42-44 Small single-institution studies with limited follow-up report that survival with UD HSCT in younger patients now approximates that of matched sibling HSCT (Table 1).45-48 However, experience from larger cohorts reported in the last 5 years from the United States, Japan, Korea, and Europe suggests that the outcome with UD HSCT is still not as favorable as that of a matched sibling donor.49-53 In recent studies, the incidence of graft failure was approximately 10%, GVHD 30% to 40%, and survival in 3 to 5 years highly variable, ranging from 42% to 94% (Table 1). One of the main difficulties in assessing outcomes with UD HSCT in SAA is the retrospective nature of most reports. Absent properly randomized or even large prospective studies, variability in patient selection and transplant regimens make general recommendations difficult. In a recent systematic review, great variability in reported outcomes was observed in UD HSCT studies in SAA.54 For example, overall survival with corresponding confidence intervals at 5 years was reported in only about half the studies analyzed, and survival rates ranged from 28% to 94%. An attempted meta-analysis of UD transplant revealed too much heterogeneity between studies that precluded a pooled analysis.54

Studies of unrelated donor stem cell transplantation in SAA

| Study (year) . | N . | Design . | Conditioning . | Graft failure, % . | Median age, y . | aGVHD grade 2-4, % . | cGVHD, % . | Survival, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim (2007)117 | 40 | Prospective | Cy/TBI | 5 | 27 | 30 | 38 | 75 (3 y) |

| Maury (2007)43 | 89 | Retrospective | Various | 14 | 17 | 50 | 28 | 42 (5 y) |

| Viollier (2008)42 * | 349 | Retrospective | Various | 11 | 18 | 28 | 22 | 57 (5 y) |

| Kosaka (2008)118 | 31 | Prospective | Cy/ATG/TBI; Flu/Cy/ATG/TBI | 16 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 93 (3 y) |

| Perez-Albuerne (2008)52 | 195 | Retrospective | Various | 15 | 10 | 43 | 35 | 51 (5 y) |

| Bacigalupo (2010)44 | 100 | Retrospective | Flu/Cy/ATG; Flu/Cy/ATG-TBI | 17 | 20 | 18 | 27 (no TBI) 50 (TBI group) | 75 (5 y) |

| Kang (2010)119 | 28 | Prospective | Flu/Cy/ATG | 0 | 13 | 46 | 35 | 68 (3 y) |

| Lee (2010)120 | 50 | Prospective | Cy/TBI | 0 | 28 | 46 | 50 | 88 (5 y) |

| Yagasaki (2010)48 | 31 | Retrospective | Various | 3 | 9 | 37 | 27 | 94 (5 y) |

| Study (year) . | N . | Design . | Conditioning . | Graft failure, % . | Median age, y . | aGVHD grade 2-4, % . | cGVHD, % . | Survival, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim (2007)117 | 40 | Prospective | Cy/TBI | 5 | 27 | 30 | 38 | 75 (3 y) |

| Maury (2007)43 | 89 | Retrospective | Various | 14 | 17 | 50 | 28 | 42 (5 y) |

| Viollier (2008)42 * | 349 | Retrospective | Various | 11 | 18 | 28 | 22 | 57 (5 y) |

| Kosaka (2008)118 | 31 | Prospective | Cy/ATG/TBI; Flu/Cy/ATG/TBI | 16 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 93 (3 y) |

| Perez-Albuerne (2008)52 | 195 | Retrospective | Various | 15 | 10 | 43 | 35 | 51 (5 y) |

| Bacigalupo (2010)44 | 100 | Retrospective | Flu/Cy/ATG; Flu/Cy/ATG-TBI | 17 | 20 | 18 | 27 (no TBI) 50 (TBI group) | 75 (5 y) |

| Kang (2010)119 | 28 | Prospective | Flu/Cy/ATG | 0 | 13 | 46 | 35 | 68 (3 y) |

| Lee (2010)120 | 50 | Prospective | Cy/TBI | 0 | 28 | 46 | 50 | 88 (5 y) |

| Yagasaki (2010)48 | 31 | Retrospective | Various | 3 | 9 | 37 | 27 | 94 (5 y) |

Outcomes shown are for the entire cohort reported in each study. Studies that include 4 or more conditioning regimens are reported as “various.” Only publications with more than 20 patients reported in the past 5 years are shown.

Cy indicates cyclophosphamide; TBI, total body irradiation; Flu, fludarabine; aGVHD, acute GVHD; and cGVHD, chronic GVHD.

In Viollier et al, only the most recent cohort (after 1998) reported is shown.

As of this writing, UD HSCT is not recommend as first therapy for SAA, even in younger patients, for the following reasons: (1) the long-term survival among children who respond to horse antithymocyte globulin (ATG) plus CsA is excellent, approximating 90%55,56 ; (2) optimal conditioning for UD HSCT is not yet defined; (3) graft rejection and GVHD remain problematic, especially in older patients; (4) chronic immunosuppression for GVHD increases mortality risk long-term31,32 ; (5) more generalizable data from larger cohorts suggest that long-term survival is closer to 50% to 60%; and (6) late effects of low dose total body irradiation and alkylating agents substituting for irradiation are not known. To some extent, these considerations are moot: practically, identification of a matched unrelated donor and coordination with a transplant center usually takes several months, and delaying definitive IST while conducting a search for a nonfamily donor may be dangerous. A consequence of high resolution molecular matching is a more limited pool of ideal donors. Nonwhite ethnic groups are relatively poorly represented in bone marrow registries, and there are biologic limits due to the complex HLA genetics in blacks and children of mixed ethnicity. Of course, a donor search should be initiated soon after diagnosis for all younger patients to assess future options should immunosuppression be ineffective.

Prospective trials using umbilical cord (UC) HSCT in SAA are limited to smaller case series, which do show encouraging results.57,58 In contrast, experience from larger cohorts in retrospective analyses indicate that overall survival is not as favorable as in pilots, at approximately 40% at 2 to 3 years.59-61 Graft rejection and poor immune reconstitution continue to limit the success of UC HSCT.61 Factors that have been associated with better outcomes are higher number of nucleated graft cells, certain conditioning regimens, and the degree of mismatch between the graft and recipient.59,61 As parameters associated with better outcomes are defined, results with UC HSCT should improve.

Immunosuppressive therapy

Standard initial IST is horse ATG and CsA, which produces hematologic recovery in 60% to 70% of cases and excellent long-term survival among responders, as shown in several large prospective studies in the United States, Europe, and Japan.1,62-66 Despite the use of different horse ATG preparations, the rates, time course, and patterns of hematologic recovery have been consistent across studies, which argues against significant lot variations affecting outcomes. As the addition of CsA to ATG increased the hematologic response rate, further attempts have been made to intensify immunosuppression and thus improve on this standard regimen. The addition of mycophenolate mofetil,67 growth factors, or sirolimus68 to horse ATG/CsA did not improve rates of response, relapse, or clonal evolution (Table 2). The use of tacrolimus as an alternative to CsA has not been systematically examined in SAA, and the experience is limited to case reports and small case series that suggest activity.69,70

Studies of alternative horse ATG/CsA regimens compared with standard horse ATG/CsA

| Study (year) . | N . | Agent(s) added to horse ATG/CsA . | Design . | Outcome compared with standard horse ATG/CsA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kojima (2000)65 | 119 | G-CSF, danazol | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, relapse, clonal evolution, or survival |

| Gluckman (2002)89 | 102 | G-CSF | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, relapse, clonal evolution, or survival |

| Zheng (2006)77 | 77 | GM-CSF, EPO | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response or survival |

| Scheinberg (2006)67 | 104 | Mycophenolate mofetil | Prospective | No difference in response, relapse, clonal evolution, or survival compared with historical control |

| Teramura (2007)92 | 101 | G-CSF | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, clonal evolution, and survival; fewer relapses in G-CSF arm |

| Scheinberg (2009)68 | 77 | Sirolimus | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, relapse, clonal evolution, or survival |

| Tichelli (2011)94 | 192 | G-CSF | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, relapse, event-free survival, and overall survival |

| Study (year) . | N . | Agent(s) added to horse ATG/CsA . | Design . | Outcome compared with standard horse ATG/CsA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kojima (2000)65 | 119 | G-CSF, danazol | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, relapse, clonal evolution, or survival |

| Gluckman (2002)89 | 102 | G-CSF | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, relapse, clonal evolution, or survival |

| Zheng (2006)77 | 77 | GM-CSF, EPO | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response or survival |

| Scheinberg (2006)67 | 104 | Mycophenolate mofetil | Prospective | No difference in response, relapse, clonal evolution, or survival compared with historical control |

| Teramura (2007)92 | 101 | G-CSF | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, clonal evolution, and survival; fewer relapses in G-CSF arm |

| Scheinberg (2009)68 | 77 | Sirolimus | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, relapse, clonal evolution, or survival |

| Tichelli (2011)94 | 192 | G-CSF | Prospective, randomized | No difference in response, relapse, event-free survival, and overall survival |

Only comparative studies that included cyclosporine with ATG are included.

EPO indicates erythropoietin.

A more lymphocytotoxic agent, rabbit ATG, has been successful in salvaging patients with refractory or relapsed SAA after initial horse ATG.71,72 This experience stimulated its use as first-line therapy and the expectation that it would produce superior outcomes compared with horse ATG.73-78 Several pilot or retrospective studies compared outcomes between the 2 ATGs (Table 3). However, in our recently reported large, randomized controlled study, hematologic response to rabbit ATG (37%) was about half that observed with standard horse ATG (68%), with inferior survival noted in the rabbit ATG arm.79 In the same study, an alemtuzumab-only treatment arm (100 mg total) was discontinued early because of a low response rate and an increase in early deaths. These data suggest that more lymphocytotoxic regimens do not yield better outcomes in SAA. Thus, horse ATG/CsA remains the most effective regimen for first-line therapy of SAA.

Studies comparing horse ATG/CsA and rabbit ATG/CsA as first therapy in SAA

| Study (year) . | Horse ATG, N . | Rabbit ATG, N . | Horse ATG formulation . | Rabbit ATG formulation . | Horse ATG, response, % . | Rabbit ATG, response, % . | Design . | Outcome comparison between ATGs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zheng (2006)77 | 47 | 32 | Lymphoglobulin | Fresenius | 79 | 53 | Prospective, randomized | Comparative statistics not reported |

| Garg (2009)74 | — | 13 | — | Thymoglobulin | — | 92 | Prospective | No comparative statistics, comparison with reported results with horse ATG in the literature |

| Atta (2010)75 | 42 | 29 | Lymphoglobulin | Thymoglobulin | 60 | 35 | Retrospective | Difference at statistical significance (historical comparison) |

| Afable (2011)111 | 67 | 20 | ATGAM | Thymoglobulin | 58 | 45 | Retrospective | Difference not statistically significant (historical comparison) |

| Scheinberg (2011)79 | 60 | 60 | ATGAM | Thymoglobulin | 68 | 37 | Prospective, randomized | Statistically significant difference (direct comparison) |

| Study (year) . | Horse ATG, N . | Rabbit ATG, N . | Horse ATG formulation . | Rabbit ATG formulation . | Horse ATG, response, % . | Rabbit ATG, response, % . | Design . | Outcome comparison between ATGs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zheng (2006)77 | 47 | 32 | Lymphoglobulin | Fresenius | 79 | 53 | Prospective, randomized | Comparative statistics not reported |

| Garg (2009)74 | — | 13 | — | Thymoglobulin | — | 92 | Prospective | No comparative statistics, comparison with reported results with horse ATG in the literature |

| Atta (2010)75 | 42 | 29 | Lymphoglobulin | Thymoglobulin | 60 | 35 | Retrospective | Difference at statistical significance (historical comparison) |

| Afable (2011)111 | 67 | 20 | ATGAM | Thymoglobulin | 58 | 45 | Retrospective | Difference not statistically significant (historical comparison) |

| Scheinberg (2011)79 | 60 | 60 | ATGAM | Thymoglobulin | 68 | 37 | Prospective, randomized | Statistically significant difference (direct comparison) |

Other studies comparing horse and rabbit ATG as first therapy have been reported in abstract form only. A small Russian prospective randomized study (32 patients in total) showed superiority of horse ATG to rabbit ATG.76 A retrospective Spanish study (35 who received horse ATG and 75 rabbit ATG) showed no difference between the ATGs; however, response rates to horse ATG were only 49%, much lower than the historical response rate for this regimen.73 A follow-up from the experience of Garg et al showed a reduction in the response rate of rabbit ATG to 62%, in a single-arm study (N = 21).78 The European Bone Marrow Transplantation Severe Aplastic Anemia Working Party conducted a matched pair analysis comparing horse an rabbit ATG: survival at 2 years was 56% for rabbit compared with 78% for horse ATG; after censoring for stem cell transplantation, survival was 39% for rabbit and 72% for horse ATG.112 In the Polish and Korean pediatric experience (n = 55 and n = 112, respectively), response rate to upfront rabbit ATG was approximately 50% at 6 months, which is lower than the historic response rate to horse ATG in this population (∼ 75%).113,114 For patients of all ages, the German and Korean experience (n = 64 and n = 58, respectively) also showed a 6-month response rate of approximately 50%, which is inferior to that of historical horse ATG as first therapy.115,116

— indicates not applicable.

Cyclophosphamide was first reported to be active in SAA in the mid 1970s in a patient who had hematologic recovery after receiving 30 mg/kg per day over 4 days.80 This experience was expanded in the 1990s using higher doses (200 mg/kg total dose) at a single institution. Response rates were comparable with horse ATG, but with apparently fewer late events (relapse and clonal evolution) in historical comparison.81 However, cyclophosphamide was found to be excessively toxic because of fungal infections and deaths in a randomized study at NIH, and relapse and clonal evolution were observed.82,83 Recently, long-term follow-up of SAA patients treated with high-dose cyclophosphamide showed that the cumulative incidence of invasive fungal infection was 21% in treatment-naive and 39% in refractory SAA.84,85 These incidences of invasive fungal infections are higher than those observed with horse ATG and represent the major toxicity of the high-dose cyclophosphamide regimen.79,82 Even patients presenting with neutrophil counts of 200 to 500/μL, who in our experience rarely develop serious fungal infections with ATG therapy, are rendered profoundly neutropenic for weeks to months by cyclophosphamide. In addition, extended support for such patients, including long periods of hospitalizations, G-CSF, and antifungal prophylaxis, may be prohibitively costly. Therefore, in view of lack of reproducibility and significant toxicity concerns, this regimen is not recommended outside a clinical research protocol.

Immunosuppression administration

ATG.

Because many hematologists may not be familiar with administration of polyclonal antibodies, such as ATG, its immediate toxicities can be daunting for inexperienced nurses and physicians, and referral to hospitals with experience in treating SAA or enrollment into research trials is to be encouraged. We perform an ATG skin test to test for hypersensitivity to horse serum and desensitize those reacting to the intradermal injection. A double lumen central line should be inserted to ease delivery of drugs and transfusions. Platelets should be maintained at more than 20 000/μL during the ATG administration period. In cases of platelet refractoriness, we test for alloantibodies to determine the need for best matched platelet products. We use universal filtration of blood products to prevent alloantibody formation. There is no formal recommendation regarding the use of irradiated blood products after horse ATG in SAA, but our practice has been to apply universal irradiation in our protocols as more immunosuppressive regimens were studied, in accordance with recent recommendations from a European study survey.86 Patients need not be free of infection before initiating ATG, but we prefer to establish responsiveness to antibiotic therapy at least for bacterial infections. However, prolonged attempts to clear fungal infections or extensive bacterial infections can delay definitive IST or HSCT therapies. We withhold β-blockers before ATG to avoid suppressing physiologic compensatory responses to anaphylaxis. ATG is better not initiated late in the day or on weekends when hospitals may be short-staffed.

ATG is usually administered at a dose of 40 mg/kg over 4 hours, daily for 4 days. Prednisone 1 mg/kg is started on day 1 and continued for 2 weeks, as prophylaxis for serum sickness. Premedication before each ATG dose with acetaminophen and diphenhydramine is conventional, and common infusion reactions are managed symptomatically with meperidine (rigors), acetaminophen (fevers), diphenhydramine (rash), intravenous hydration (hypotension), and supplemental oxygen (hypoxemia). Occasionally, hemodynamic and/or respiratory compromise can precipitate transfer to the intensive care unit, vasopressor support, and, rarely, intubation. In the presence of life-threatening reactions, the ATG infusion is slowed or held temporarily until alarming signs and symptoms subside. Depending on the severity of reactions, we reinitiate ATG at the normal or a slower infusion rate (sometimes over 24 hours) in a monitored setting. Increased liver enzymes tend to normalize over several days, and ATG may be infused despite mild to moderate elevation in transaminases. Changing ATG formulations (from horse to rabbit, for example) should not be used as strategy to manage infusion-related toxicities. For rising creatinine, CsA can be withheld temporarily until renal function improves. With this approach, a complete ATG course is accomplished in nearly all patients in our experience.

Cyclosporine.

We initiate CsA on day 1 to a target trough level between 200 and 400 ng/mL, starting at a dose of 10 mg/kg per day (in children, 15 mg/kg per day).79 Many patients develop hypertension during CsA treatment, and amlodipine is preferred because of minimal overlap with CsA toxicities. Bothersome gingival hyperplasia can improve on a short course of azithromycin.87 Calcium channel blockers have been associated with worse gingival hyperplasia when combined with CsA.88 In general, we continue CsA in the setting of modest increases in creatinine, with careful monitoring of renal function and adjustment of dosing to achieve target CsA levels. Fine-tuning of the CsA dose to the lower end of the therapeutic range, optimization of blood pressure control, adequate hydration, and avoidance of other nephrotoxic agents can improve the tolerability and allow for continued CsA use. More serious compromise of kidney function from baseline (creatinine > 2 mg/mL) may require temporary cessation of CsA with later reintroduction at lower doses, with further increases as tolerated.

G-CSF.

G-CSF has been extensively studied in combination with immunosuppression in prospective randomized trials, but these have consistently failed to show benefit in hematologic response or survival in SAA (Table 2).65,77,89-94 Of concern is that G-CSF has been associated with an increased risk of clonal evolution in some retrospective studies,95-97 but this observation has not been confirmed by others.98 Therefore, because of the lack of benefit and the theoretical risk for potential harm, G-CSF is not recommended with ATG in our protocols. The decision to attempt to improve neutrophil with G-CSF is based on clinical grounds in selected patients who are actively infected and persistently severely neutropenic (< 200/μL), with reassessment and discontinuation after no more than a few days or weeks if there is no significant response.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis.

As anti–Pneumocystis carinii prophylaxis, we routinely use monthly aerosolized pentamidine while patients are on therapeutic doses of CsA. This regimen was introduced after we observed several cases of P carinii pneumonia at our institution in the late 1980s in AA patients who were treated with horse ATG and CsA. Sulfa drugs are avoided because of their myelosuppressive properties, but alternative regimens with dapsone or atovaquone are sometimes used when aerosolized pentamidine cannot be tolerated or in very small children. Antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal prophylaxes are not routinely administered with standard horse ATG/CsA but have been used in the context of investigational regimens that are more immunosuppressive.

How we manage SAA after ATG

We use a simple definition for hematologic response: no longer meeting blood count criteria of SAA, which closely correlates with transfusion independence and long-term survival.63,99 Hematologic improvement is not to be expected for 2 to 3 months after ATG; therefore, management of patients in this period requires careful and consistent attention. The majority of responses (90%) occur within the first 3 months, with fewer patients responding between 3 and 6 months or after.99 After ATG treatment, the threshold for prophylactic platelet transfusion is reduced to 10 000/μL (or for bleeding). Transfusion of red cells aims to alleviate symptoms of anemia, not simply to target a specific hemoglobin threshold. Adequate red blood cell transfusions in symptomatic patients should not be deferred because of fear of iron accumulation or to reduce the risk of alloimmunization. In evaluating febrile neutropenic patients, simple chest x-ray is of limited value, and we routinely pursue CT imaging of the sinus and chest followed by nasal endoscopy, bronchoscopy, and biopsy for microbiologic confirmation when indicated. If fungal infection is suspected or neutropenic fever persists for more than several days despite broad-spectrum antimicrobials, empiric antifungal therapy should include drugs active against Aspergillus sp, as this pathogen has remained the most common fungal isolate in SAA patients for the past 20 years.100

Management of responders to immunosuppression

Cyclosporine taper is common practice and seems logical, but adequate prospective comparative studies of such a strategy are lacking. Anecdotal and retrospective reports support a taper to decrease the rate of relapse.101 To 2003, we discontinued CsA at 6 months among responders67,99 ; since 2003, we have included a CsA taper in all patients who responded to horse ATG/CsA. Despite this change in practice, we have not observed a reduction in the rate of relapse compared with our large historical experience.

Fluctuations in blood counts are frequent in the weeks after immunosuppression, and too close scrutiny of small changes in hematologic laboratory values for glimmers of a response is not helpful. We assess for response at 3- and 6-month landmark visits. Meaningful improvement may be evident earlier; neutrophils may increase within a few weeks of ATG administration. Complete normalization of blood counts is not seen in the majority of patients, although continued improvement may occur over time, sometimes over years. The long-term survival benefit of immunosuppression with horse ATG applies to all responders, partial and complete,99 and there is no rationale to pursue further immunosuppression (or HSCT!) in responding cases.

Refractory SAA

For protocol purposes, we define refractory SAA as blood counts still fulfilling criteria for severe pancytopenia 6 months after initiation of IST. Fortunately, in our experience, approximately half the patients classified as nonresponders at 6 months will have had an improvement in neutrophil count. Even an increase in granulocytes to 200/μL or higher generally avoids life-threatening infections and provides time to carefully weigh options for further treatment; conversely, persistent severe neutropenia accelerates decision-making and may increase the desirability of more aggressive therapies, such as matched/mismatched UD transplants or matched sibling transplants in older patients.

Most marrow failures experts now agree that younger patients who have not responded to immunosuppression should consider a UD HSCT, especially if a high-resolution genetic match has been identified (Figure 1). For patients who lack a histocompatible donor or are not suitable for HSCT, a second course of immunosuppression with rabbit ATG/CsA is efficacious in 30% to 70% of cases.71,72 We found alemtuzumab monotherapy (without CsA) equivalently effective as was rabbit ATG/CsA in a randomized study, with hematologic response observed in 30% to 40% of patients.102 Alemtuzumab may be an alternative to rabbit ATG in refractory SAA and may appeal to older patients or those who experienced significant toxicities with CsA (Figure 1).

Although 75% to 90% of patients will achieve hematologic recovery after one or 2 courses of IST, the mechanisms by which some patients persist with severe pancytopenia remain elusive. In some patients, stem cell numbers may be too few to reconstitute adequate hematopoiesis, even after removal of an acute immune insult. Other possible explanations for failure to respond to ATG include a nonimmune etiology, inadequacy of current immunosuppressive agents, negative regulation of hematopoiesis by stromal elements, or an underlying telomeropathy. Interventions, such as androgens, eltrombopag, and novel immunosuppressants, are being tested for their activity to circumvent these shortcomings.

Although androgens lacked efficacy in early randomized studies when combined with ATG,65,103,104 anecdotal experience from uncontrolled studies suggest that these agents can be beneficial in some patients, leading to sustained hematologic recoveries.105,106 In patients who are refractory to IST and lack good HSCT options, we offer a trial of androgen therapy for 3 months. Androgens may be particularly useful in patients with telomeropathies.

In a pilot trial at our institution, single-agent oral eltrombopag produced hematologic responses in 11 of 25 cases, with trilineage responses observed in some, suggesting a stimulatory effect of early myeloid progenitors.107 Current NIH protocols are testing this thrombopoietin mimetic in combination with ATG.

When neutropenia is not severe, some persistently pancytopenic patients can be supported for many years with transfusions, chelation, and hematopoietic growth factors.100

How we follow SAA long term

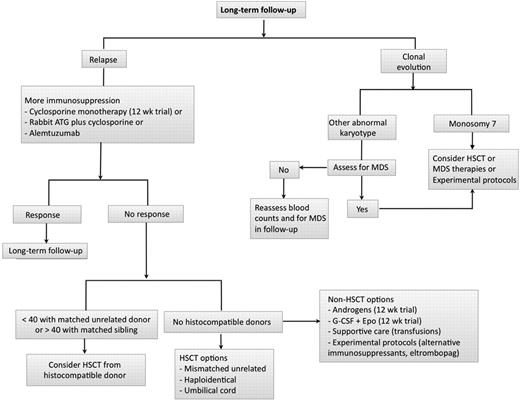

Responders should be followed for late complications of relapse and clonal evolution (Figure 2). We assess for bone marrow morphology and especially karyotype at 6 and 12 months after treatment and then yearly to monitor for evolution. A hypocellular marrow should not be equated with persistent SAA or relapse in the setting of improving blood counts, as marrow cellularity often does not correlate with blood counts. Blood counts, not marrow cellularity, should guide management.

Long-term follow-up after immunosuppression. In patients treated with immunosuppression, we follow for relapse (among responders) and clonal evolution in all patients. A gradual downtrend in blood counts may signify hematologic response, underscoring the important of routine monitoring in this setting. In cases of relapse, we usually reintroduce more immunosuppression in the form of oral cyclosporine and/or a repeat course with rabbit ATG/CsA or alemtuzumab. In those who are unresponsive to more immunosuppression, further management will depend on suitability for HSCT (age, donor availability, comorbidities). When only higher risk HSCT options are available (mismatched unrelated, haploidentical, umbilical cord), we consider nonimmunosuppressive strategies, such as androgens (12-week trial), combination growth factors (G-CSF + Epo for 12 weeks), or experimental therapies. In patients with a very low neutrophil count unresponsive to G-CSF associated with infections, we consider a higher risk HSCT in younger patients. We monitor for clonal evolution by repeated marrow karyotype assessment at 6 and 12 months and then yearly thereafter. After 5 years, we tend to increase the interval between bone marrows. When faced with an abnormal karyotype, such as del13q, trisomy 6, pericentric inversion of chromosome 1;9, del20q, or trisomy 8, we assess for myelodysplasia by looking at blood counts, peripheral smear, and bone marrow morphology. On occasion, these karyotypes may not equate to progression to myelodysplasia and not be detected on repeated marrow examination. In cases where there is worsening blood counts and/or more significant dysplastic changes in the marrow, our approach is to seek transplant options, therapies for myelodysplasia, or a clinical trial. Monosomy 7 is almost never a transient finding and commonly associates to a more rapid progression to myelodysplasia and leukemia. In these cases, our approach is to seek HSCT earlier.

Long-term follow-up after immunosuppression. In patients treated with immunosuppression, we follow for relapse (among responders) and clonal evolution in all patients. A gradual downtrend in blood counts may signify hematologic response, underscoring the important of routine monitoring in this setting. In cases of relapse, we usually reintroduce more immunosuppression in the form of oral cyclosporine and/or a repeat course with rabbit ATG/CsA or alemtuzumab. In those who are unresponsive to more immunosuppression, further management will depend on suitability for HSCT (age, donor availability, comorbidities). When only higher risk HSCT options are available (mismatched unrelated, haploidentical, umbilical cord), we consider nonimmunosuppressive strategies, such as androgens (12-week trial), combination growth factors (G-CSF + Epo for 12 weeks), or experimental therapies. In patients with a very low neutrophil count unresponsive to G-CSF associated with infections, we consider a higher risk HSCT in younger patients. We monitor for clonal evolution by repeated marrow karyotype assessment at 6 and 12 months and then yearly thereafter. After 5 years, we tend to increase the interval between bone marrows. When faced with an abnormal karyotype, such as del13q, trisomy 6, pericentric inversion of chromosome 1;9, del20q, or trisomy 8, we assess for myelodysplasia by looking at blood counts, peripheral smear, and bone marrow morphology. On occasion, these karyotypes may not equate to progression to myelodysplasia and not be detected on repeated marrow examination. In cases where there is worsening blood counts and/or more significant dysplastic changes in the marrow, our approach is to seek transplant options, therapies for myelodysplasia, or a clinical trial. Monosomy 7 is almost never a transient finding and commonly associates to a more rapid progression to myelodysplasia and leukemia. In these cases, our approach is to seek HSCT earlier.

Hematologic relapse

There is no consensus on the definition of relapse. Pragmatically and in the clinical research setting, we have defined relapse when reintroduction of immunosuppression is required for decreasing blood counts, usually, but not always, accompanying reinstitution of transfusions.99 A trend, not a single blood count is preferred, and avoids over-interpretation of oscillating numbers that can occur normally or in the setting of infection. In cases of frank recurrence of pancytopenia, the need for renewed therapy is obvious. A bone marrow examination should be performed at relapse to exclude clonal evolution.

Relapse is most simply treated with reintroduction (or dose increase) of CsA for 2 to 3 months. In responders, we then continue CsA until counts have improved and stabilized, aiming to very gradually taper the drug as tolerated to the minimal dose (or to off) needed to maintain adequate counts, a process that may take years. When CsA alone is ineffective, a second course of rabbit ATG/CsA yields responses in approximately 50% to 60% of cases.71 Alemtuzumab monotherapy (without CsA) may be similarly useful.102 We do not usually recommend UD HSCT on first relapse in younger patients because most will respond to further immunosuppression. Relapse alone has not been correlated to worse survival in SAA.99

Clonal evolution

The most concerning late event in SAA is clonal evolution to MDS and leukemia. This complication occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of patients and usually manifests as worsening blood counts unresponsive to immunosuppression, prominent dysplastic findings in the bone marrow, and abnormal cytogenetics. Occasionally, a cytogenetic abnormality is reported in routine follow-up marrows despite good blood counts and without a dysplastic marrow. Interpretation of such an abnormality is not clear. Repeating the bone marrow in several months is reasonable, and some clonal abnormalities appear to be transient and may not predict or precede worse blood counts (Figure 2). One exception is monosomy 7, which is almost always a dire finding108 ; in these cases, we pursue HSCT as the only potentially curative therapy.

Durability of response

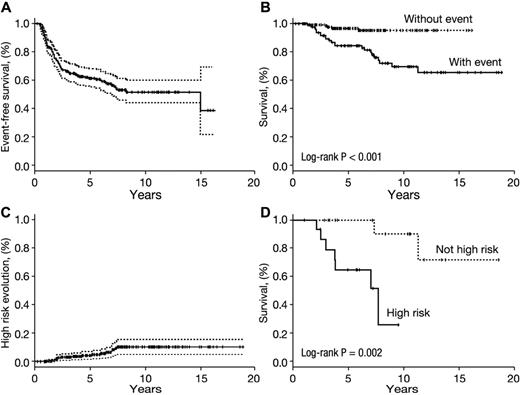

The goals of immunosuppression are improved life expectancy and a durable hematologic response that avoids relapse and clonal evolution. In our experience, hematologic relapse and clonal evolution usually occur within 2 to 4 years of IST.67,68,99 Approximately 50% of responders neither relapse nor evolve long term (Figure 3A), and they have excellent long-term survival (Figure 3B). Most patients who relapse can be rescued with further immunosuppression or by HSCT. In contrast, clonal evolution usually confers a poor prognosis.108 Among NIH patients, evolution to monosomy 7, high-grade MDS, complex karyotype, and leukemia are infrequent (Figure 3C) but greatly decreases survival compared with less high-risk forms of evolution (Figure 3D).

Durability of response after horse ATG. (A) Time to first late event among responders. The probability of a first late event (relapse or clonal evolution) among responders (N = 243) is approximately 50%. (B) In those who do not experience a late event, long-term survival in 10 years is excellent at 95%, whereas in those who experience a late event survival is not as favorable (65% in 10 years). (C) In our experience, high-risk evolution to monosomy 7, complex karyotype, high-grade myelodysplasia, or leukemia occurs in approximately 10% of responders long term. (D) Among responders who clonally evolved (any cytogenetic abnormality), survival was worse in those with a high-risk clonal event (monosomy 7, high-grade myelodysplasia, complex karyotype, or leukemia) compared with responders who do not experience high-risk evolution (principal karyotype findings in this lower risk group were trisomy 8 and del13q). Of note, among the high-risk clonal evolutions in responders, all occurred in those who achieved a partial hematologic response at 6 months after immunosuppression. (A,C) SD values (P = log-rank). Day 0 for all curves is the time of first horse ATG-based therapy. Data for other experimental immunosuppressive therapies as first-line are not shown. A late event is defined as either relapse or clonal evolution, whichever occurred first. Patients with repeated relapses or cytogenetic abnormalities were counted once at the time of first event.

Durability of response after horse ATG. (A) Time to first late event among responders. The probability of a first late event (relapse or clonal evolution) among responders (N = 243) is approximately 50%. (B) In those who do not experience a late event, long-term survival in 10 years is excellent at 95%, whereas in those who experience a late event survival is not as favorable (65% in 10 years). (C) In our experience, high-risk evolution to monosomy 7, complex karyotype, high-grade myelodysplasia, or leukemia occurs in approximately 10% of responders long term. (D) Among responders who clonally evolved (any cytogenetic abnormality), survival was worse in those with a high-risk clonal event (monosomy 7, high-grade myelodysplasia, complex karyotype, or leukemia) compared with responders who do not experience high-risk evolution (principal karyotype findings in this lower risk group were trisomy 8 and del13q). Of note, among the high-risk clonal evolutions in responders, all occurred in those who achieved a partial hematologic response at 6 months after immunosuppression. (A,C) SD values (P = log-rank). Day 0 for all curves is the time of first horse ATG-based therapy. Data for other experimental immunosuppressive therapies as first-line are not shown. A late event is defined as either relapse or clonal evolution, whichever occurred first. Patients with repeated relapses or cytogenetic abnormalities were counted once at the time of first event.

Prospects for improved management of SAA

Measurement of telomere length and blood counts offer the possibility of rational risk stratification of treatment in future protocols. In a recent report, pretreatment telomere length correlated with relapse, clonal evolution, and survival.109 Patients with shorter telomeres in peripheral blood leukocytes were about twice as likely to relapse and 4- to 6-fold more likely to evolve to MDS or leukemia, with a negative impact on survival.109 If confirmed in other series, this assay might also be useful in determining the level of risk and need for monitoring of patients after IST. Patients with normal telomere length and good reticulocyte numbers at diagnosis do well long-term after immunosuppression with horse ATG and CsA.109 Conversely, short telomeres and low reticulocytes might direct patients to therapies that offer better than 50% long-term survival. Other biomarkers or pathophysiologic indicators should emerge from global assessments of the immune response and more sensitive measurements of stem cell reserve and function.

For HSCT, the critical issues are extending sibling transplant to older patients, essentially improving the prevention and management of GVHD, and providing alternative donor transplants to patients who lack family donors. In the latter circumstance, how much histocompatibility mismatch can be tolerated? How many patients are likely to find suitable donors in the registries in a timely manner? Is there an advantage to earlier transplant? Registry data will be critical to avoid the “winner's” curse of single-institution study reports.110

For IST, the exact mechanism of ATG action on the immune (and hematopoietic?) system will be sought but may not be easily found. Further intensification of immunosuppression, by addition of agents beyond CsA or substitution of more potent ATG or cyclophosphamide, has not been successful. More appealing options are sequential approaches (such as repeated courses of ATG) and addition of complementary drugs, such as androgens and novel growth factors (such as eltrombopag), to assist in tissue regeneration and amplification of stem cell numbers. In the minority of patients with defined genetic lesions, especially of telomerase components, the special role of androgens in improving organ function and also stabilizing or even elongating telomeres should be studied in systematic protocols.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Colin Wu for assistance in generating the Kaplan-Meier curves.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.S. and N.S.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Phillip Scheinberg, Hematology Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 10 Center Dr, Bldg 10 CRC, Rm 3E-5140, MSC 1202, Bethesda, MD 20892-1202; e-mail: scheinbp@mail.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal