Abstract

The function of T-cell receptor (TCR) gene modified T cells is dependent on efficient surface expression of the introduced TCR α/β heterodimer. We tested whether endogenous CD3 chains are rate-limiting for TCR expression and antigen-specific T-cell function. We show that co-transfer of CD3 and TCR genes into primary murine T cells enhanced TCR expression and antigen-specific T-cell function in vitro. Peptide titration experiments showed that T cells expressing introduced CD3 and TCR genes recognized lower concentration of antigen than T cells expressing TCR only. In vivo imaging revealed that TCR+CD3 gene modified T cells infiltrated tumors faster and in larger numbers, which resulted in more rapid tumor elimination compared with T cells modified by TCR only. After tumor clearance, TCR+CD3 engineered T cells persisted in larger numbers than TCR-only T cells and mounted a more effective memory response when rechallenged with antigen. The data demonstrate that provision of additional CD3 molecules is an effective strategy to enhance the avidity, anti-tumor activity and functional memory formation of TCR gene modified T cells in vivo.

Introduction

Retroviral T-cell receptor (TCR) gene transfer is an attractive strategy by which large numbers of antigen-specific T cells can be generated for adoptive transfer.1-4 One of the advantages of this technique is that it can be used to circumvent possible impairment of autologous T-cell responses against tumor associated antigens as it bypasses central tolerance.5 In addition, the introduced TCR specificity can be targeted against poorly immunogenic antigens and high affinity TCR can be selected for transfer.6 This method has recently seen success in the first clinical trial of TCR gene therapy, where MART1 specific T cells, generated by retroviral gene transfer, were adoptively transferred into patients with metastatic melanoma. The engineered T cells engrafted in 15 of 17 patients, 2 of whom demonstrated long term tumor regression.7 T cells engineered to express CEA-specific TCR also induced a decrease in CEA levels in 3 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, and regression of tumor metastases in 1 patient, but were associated with a severe colitis in all 3 patients.8 The most promising results were seen after adoptive transfer of TCR transduced T cells specific for the NY-ESO-1antigen which resulted in clinical responses in synovial cell sarcoma and in melanoma.9

As the density of TCR on the surface of cells affects their functional avidity, inefficient TCR expression may impair the success of TCR gene therapy.10-14 Several different strategies have been developed to increase the expression of introduced α and β chains by reducing the mispairing with endogenous TCR chains. The strategies include replacing the human TCR constant domain with murine sequences, the introduction of an additional disulphide bond into the constant regions, and the production of hybrid molecules consisting of the extracellular portion of TCR chains fused to the intracellular CD3ζ domain.15-18

TCR α and β chains form a complex with 4 invariant CD3 chains: γ,δ,ϵ and ζ. This complex formation is required in order for the TCR to be expressed on the cell surface, and for signal transduction on antigen recognition. TCR introduced by retroviral gene transfer are likely to be in competition with endogenous TCR molecules for CD3 chains. We used a murine model system to explore whether the co-transfer of TCR genes together with the genes encoding the γ,δ,ϵ and ζ chains of the CD3 complex can augment TCR expression. Two different TCR, with specificity for Wilms' Tumor antigen 1 (WT1) and influenza nucleoprotein, were used to demonstrate that CD3 is rate limiting for the expression of introduced TCR in gene modified T cells. Co-transduction of CD3 and TCR genes resulted in up to 16-20 fold increase in TCR surface expression and tetramer binding compared with transduction of TCR genes alone. The increase in TCR expression was associated with increased T-cell avidity leading to improved recognition of low concentration of peptide antigen. In vivo TCR+CD3 co-transduced T cells eradicate tumors faster than TCR-only transduced T cells, which was associated with faster tumor infiltration by TCR+CD3 co-transduced T cells. The data indicate that transfer of CD3 genes enhanced the functional avidity and anti-tumor immunity of TCR gene modified T cells in vivo.

Methods

Mice

All animals were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at University College London. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the United Kingdom Home Office regulations. Thy1.1+ C57BL/6 Luciferase+ transgenic mice were a kind gift from Dr Robert Zeiser (Freiburg University, Germany).19

Cell lines, tetramers, and peptides

Phoenix-Eco (PhEco) adherent packaging cells (Nolan Laboratory) were transiently transfected with retroviral vectors for the generation of supernatant containing the recombinant retrovirus required for infection of target cells. Cells (58α−β−) are TCR-negative variant of the D0-11.10 T-cell hybridoma cell line.20 The HLA-A2–positive T2 cell line is deficient in the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) and can be efficiently loaded with exogenous peptides.21 RMA-S cells are the murine equivalent to T2, a TAP deficient derivative of the RMA cell line, which can efficiently present exogenously loaded peptide.22,23 EL4.NP is a murine lymphoma cell line, stably expressing the influenza A virus nucleoprotein (NP), a kind gift from Dr B. Stockinger (National Institute for Medical Research, London). EL4.NP. Luciferase+ cells were generated through transfection of EL4.NP cells with a red shifted luciferase plasmid, a kind gift from Dr Martin Pule (University College London, United Kingdom).

Tetramers consisted of pWT126 bound to HLA-A*0201 (Beckman Coulter) and pNP366 bound to H2-Db (Proimmune). All peptides were obtained from. HLA-A2–binding peptides: pWT126 corresponds to amino acids 126-134 (RMFPNAPYL) of the Wilms' tumor protein (WT1) and pMel corresponds to amino acids ELAGIGILTV of the MelanA/MART1 melanoma antigen. The influenza A virus NP-derived peptide, pNP366 (ASNENMDAM), and the control peptides pMDM100 (YAMIYRNL) and pSV9 (FAPGNYPAL) are presented by H2-Db class I molecules.

Vectors

The retroviral F5-TCR vector pMP71-TCRα-2A-TCRβ was modified from pMX-TCRα-IRES-TCRβ (a kind gift from Prof T. Schumacher, Netherland Cancer Institute, Amsterdam24 ). The F5-TCR recognizes the influenza A virus NP (NP366-379) peptide in the context of murine Db MHC class I. The pMX-TCRα-IRES-TCRβ was used for the initial experiments including transduction of 58α−β− cells and the preliminary experiments on primary T cells; the subsequent experiments on primary T cells were performed using pMP71-TCRα-2A-TCRβ. The pMP71-CD3ζ-CD3ϵ-CD3γ-CD3δ-IRES-GFP (CD3-GFP) was modified from the retroviral vector pMSCV-CD3δ-CD3γ-CD3ϵ-CD3ζ-IRES-GFP (a kind gift from Dr D. Vignali, University of Tennessee Medical Center25 ) and synthezised by Geneart. The 2A sequences linking the CD3 chains are unchanged from the original CD3 vector, but the CD3 genes have been codon optimized and cloned into the pMP71 vector. The WT1-TCR recognizes the pWT126 peptide in the context of HLA-A*0201. The constant regions of the α and β TCR chains have been replaced with murine constant regions, which also contain an additional cysteine residue and have been codon optimized, as described previously.17,26 This TCR was inserted into the pMP71 vector.

Retroviral transduction

The PhEco adherent packaging cells were transfected using either Calcium phosphate precipitation (Invitrogen) or Fugene HD (Roche) with the pCL-Eco construct and either F5-TCR, WT1-TCR, CD3-GFP, or GFP-control vector according to manufacturers' instructions. Splenocytes were harvested from C57BL/6 (H2b) female mice and activated with concanavalin (Con) A (2μg/mL) and IL-7 (1ng/mL) for 24 hours. Where stated, splenocytes were Vβ11 depleted and CD8+ T cells selected using MACS beads, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). After 24 hours, the viral supernatant was harvested from the transfected PhEco cells and used to transducer 6 × 106 activated splenocytes by coculture on retronectin-coated (Takara-Bio Inc) 6-well plates, in the presence of IL-2 (100 units/mL; Chiron). 58α−β− cells were transduced with the same protocol, without activation or IL-2 addition.

Cell separation

Selection of CD8+ T cells was done using anti-CD8 MACSbeads on midiMACS (Miltenyi Biotec) and LS separation columns, according to manufacturer's instructions. This routinely gave a purity of CD8+ T cells > 95% as determined by flow cytometry.

Transduced 58α−β− and CD8+ T cells were stained with anti-murine Vβ11 mAb (BD, Biosciences) and then sorted for Vβ11 and GFP by FACSAria (BD Biosciences). This routinely gave a purity of > 85% for transduced cells as determined by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Transduced cells were stained with anti-murine Vβ11, CD8, Thy1.1, CD44, CD62L (BD Biosciences) and/or anti–human Vβ2 mAbs (Immunotech) and tetramer (3.3 μg/mL). All data acquisition was performed on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FACSDiva Version 5.0.3 software (BD Biosciences).

Intracellular cytokine staining and proliferation assay

For co-culture assays, 1 × 106 transduced T cells were cultured with 1 × 106 peptide-loaded and irradiated RMA-S, T2 (50 Gy) or splenocytes (25 Gy) in 24 well plates. After 24 hours at 37°C, 5% (vol/vol) CO2, transduced T cells were examined by flow cytometry. Intracellular IFNγ and IL-2 expression in transduced T cells were detected using the BD Perm/fix kit with Brefeldin A (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions and stained with anti–IFNγ or anti–IL-2 antibodies (BD Biosciences).

T-cell proliferation assays were performed as described previously.24 Briefly, 1 × 105 peptide-loaded splenocytes were irradiated and incubated with 1 × 105 transduced CD8+ T cells, purified by FACSAria, in triplicate. Co-cultures were left at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48 hours. For the final 18 hours, cells were pulsed with 1 μCi/well 3H-thymidine (Amersham Life Sciences). The cells were harvested using a 96-well plate harvester (Amersham Life Sciences), and thymidine incorporation was measured by a γ counter (Wallace).

ELISA

Peptide-loaded RMA-S (1 × 105), splenocytes or T2 cells were irradiated and incubated with 1 × 105 transduced splenocytes or 1 × 105 transduced 58α−β−cells, in triplicate. After 24-48 hours, the supernatant was harvested and tested in an IL-2 or IFNγ ELISA assay, using a Beckon Dickinson OptEIA mouse ELISA set, according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences).

In vivo tumor protection

Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 mice were sub-lethally irradiated (5.5 Gy) followed by subcutaneous inoculation of 1 × 106 EL4.NP or EL4.NP.Luciferase+ on day 0. On day 1, mice were injected intravenously with 3 × 105 Thy1.1+ Mock, TCR, or TCR+CD3 transduced T cells. For in vivo T-cell imaging, 3 × 105 TCR-transduced Thy1.1+ T cells from Luciferase transgenic mice were injected. Tumors were measured with calipers at different intervals and the growth evaluated applying the following formula (a2 × b/2), where a = horizontal diameter and b = vertical diameter of the tumor. For assessment of T-cell accumulation in the tumor draining lymph nodes (TDLN) and the spleen, mice were killed after tumor was cleared and spleen, TDLN and nondraining LN were harvested.

In vivo bioluminescence imaging

Animals were injected intraperitoneally with D-Luciferin firefly (Biosynth) at 7.5 mg/kg (for EL4.NP.Luciferase+ imaging) or 15 mg/kg (for Luciferase+ T cells). Ten minutes after injection mice were anaesthetized and imaged by Xenogen IVIS-100 (Caliper Life Sciences).

Using an in vivo titration assay, an estimate of the number of T cells infiltrating the tumor site was calculated. Briefly, luciferase+ T cells were mock transduced and decreasing numbers were injected subcutaneously in shaved C57BL/6 mice. Immediately after injection, mice received 15 mg/kg luciferin intravenously and were imaged by IVIS-100. A correlation between the number of photons/s detected by the imaging and the number of T cells was calculated and used to estimate the number of infiltrating luciferase+ T cells at the tumor site.

Statistical analysis

P values were calculated with the Student t test using Prism 4.03 software (GraphPad), with 2-tailed distribution and 2-sample equal variance parameter.

Results

CD3 is rate limiting for TCR expression and function in murine T lymphoma cells

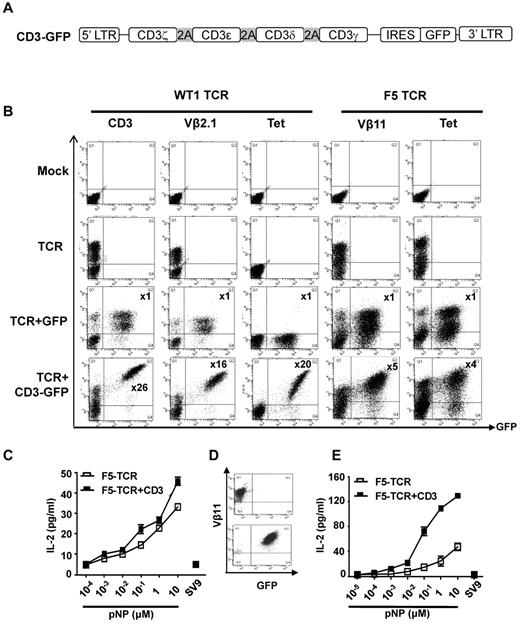

Initial experiments were performed in 58α−β− cells, a murine lymphoma cell line that expresses endogenous CD3 molecules, but no TCRα or β chains. Because assembly of CD3-TCR complexes cannot occur, CD3 is not detectable on the surface of these cells. These cells were transduced with retroviral TCR vectors and with a retroviral construct containing the CD3 γδϵ and ζ genes linked via 2A sequences (Figure 1A). Two different TCR were used in this study: (1) F5-TCR and (2) WT1-TCR. The murine F5-TCR is specific for an influenza nucleoprotein-derived peptide (pNP) presented by H2-Db. The TCR uses murine Vα6 and Vβ11 variable segments, and anti-murine Vβ11 antibodies and H2Db/pNP tetramers were used to detect TCR expression on the surface of transduced cells. The human WT1-TCR is specific for the WT1-derived peptide pWT126 presented in the context of HLA-A*0201. This TCR uses the human Vα1.5 and Vβ2.1 gene segments, and anti-human Vβ2.1 antibodies and HLA-A2/pWT126 tetramers were used to monitor TCR expression. The constant, transmembrane and cytosolic domains of the human TCR were replaced with murine sequences to facilitate expression in murine cells.

CD3 is rate limiting for expression and function of the WT1-TCR and the F5-TCR in T lymphoma cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the CD3 vector. The 4 CD3 chains (ζ-ϵ-δ-γ) are linked by the 2A sequences, followed by IRES and GFP. (B) T lymphoma cells (58α−β−) were mock-transduced or transduced with WT1-TCR, WT1-TCR+control-GFP, or WT1-TCR+CD3-GFP, then stained with antibodies against CD3, Vβ2.1, or with HLA-A2/pWT126 tetramer. Cells (58α−β−) transduced with F5-TCR, F5-TCR+control-GFP or F5-TCR+CD3-GFP, were stained with antibodies against Vβ11 or H2Db/pNP tetramer. The numbers in the panels in TCR+CD3-GFP transduced cells indicate the fold increase in the level of CD3 or TCR expression (measured by MFI) in cells expressing TCR+CD3-GFP (Q2) compared with the cells expressing TCR only (Q1). No increase in CD3 or TCR expression was seen in cells transduced with TCR+control-GFP. The data are representative of 5 performed experiments. (C) Bulk transduced 58α−β− cells were stimulated with RMA-S cells coated with increasing concentrations of pNP peptide or 10μM pSV9 control peptide. Supernatant was harvested and assessed for IL-2 production by ELISA. The graph demonstrates the mean IL-2 concentration ± SD of triplicate values. (D) Transduced 58α−β− cells were purified by FACS to obtain cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3. (E) FACS purified 58α−β− cells were stimulated with RMA-S cells coated with increasing concentrations of pNP peptide or 10μM pSV9 control peptide. Supernatant was harvested and assessed for IL-2 production by ELISA. The graph demonstrates the mean IL-2 concentration ± SD of triplicate values.

CD3 is rate limiting for expression and function of the WT1-TCR and the F5-TCR in T lymphoma cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the CD3 vector. The 4 CD3 chains (ζ-ϵ-δ-γ) are linked by the 2A sequences, followed by IRES and GFP. (B) T lymphoma cells (58α−β−) were mock-transduced or transduced with WT1-TCR, WT1-TCR+control-GFP, or WT1-TCR+CD3-GFP, then stained with antibodies against CD3, Vβ2.1, or with HLA-A2/pWT126 tetramer. Cells (58α−β−) transduced with F5-TCR, F5-TCR+control-GFP or F5-TCR+CD3-GFP, were stained with antibodies against Vβ11 or H2Db/pNP tetramer. The numbers in the panels in TCR+CD3-GFP transduced cells indicate the fold increase in the level of CD3 or TCR expression (measured by MFI) in cells expressing TCR+CD3-GFP (Q2) compared with the cells expressing TCR only (Q1). No increase in CD3 or TCR expression was seen in cells transduced with TCR+control-GFP. The data are representative of 5 performed experiments. (C) Bulk transduced 58α−β− cells were stimulated with RMA-S cells coated with increasing concentrations of pNP peptide or 10μM pSV9 control peptide. Supernatant was harvested and assessed for IL-2 production by ELISA. The graph demonstrates the mean IL-2 concentration ± SD of triplicate values. (D) Transduced 58α−β− cells were purified by FACS to obtain cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3. (E) FACS purified 58α−β− cells were stimulated with RMA-S cells coated with increasing concentrations of pNP peptide or 10μM pSV9 control peptide. Supernatant was harvested and assessed for IL-2 production by ELISA. The graph demonstrates the mean IL-2 concentration ± SD of triplicate values.

As expected mock transduced 58α−β− cells did not stain with anti-CD3 or anti-TCR antibodies (Figure 1B). After transduction with the WT1-TCR alone, a large proportion of 58α−β− cells were Vβ2.1 positive. Cotransduction with the CD3-GFP vector and the WT1-TCR vector resulted in a 26-fold increase in the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD3 expression in the GFP+ cells compared with the GFP− cells (Figure 1B). Similarly, a 16-fold increase in Vβ2.1 staining and a 20-fold increase in tetramer binding intensity was seen in GFP+ cells compared with GFP− cells (Figure 1B). Co-transduction of the WT1-TCR with a GFP control vector did not increase the level of CD3 or Vβ2.1 staining, indicating that the increase observed with the CD3-GFP vector was not because of inappropriate compensation of the GFP-positive cell populations. Similar results were obtained when this experiment was performed with the F5-TCR. Mock transduced 58α−β− cells did not stain with Vβ11 antibody nor bind H2Db/pNP tetramer (Figure 1B). The 58α−β− cells co-expressing CD3-GFP and TCR displayed 5-fold higher Vβ11 staining and 4-fold higher tetramer-binding than the GFP-negative cells expressing the F5-TCR only. Again, co-transduction with a GFP control vector did not increase Vβ11 expression or tetramer staining. These experiments indicated that the TCR expression in 58α−β− cells is substantially increased when exogenous CD3 is supplied, indicating that the level of endogenous CD3 is rate limiting for optimal TCR expression.

We next explored whether increased F5-TCR expression correlated with improved antigen-specific function. Transduced 58α−β− cells were stimulated with Tap-deficient RMA-S stimulator cells coated with decreasing concentrations of pNP peptide followed by measurement of peptide-specific IL-2 production. The analysis of bulk transduced cells showed slightly more efficient IL-2 production by cells transduced with TCR+CD3 compared with TCR alone (Figure 1C). The modest difference might be because of the fact that bulk 58α−β− cells transduced with retroviral CD3 and TCR vectors contained not only cells expressing TCR+CD3 but also cells expressing TCR only (Figure 1B). Hence, flow cytometric sorting was used to purify cells expressing TCR and CD3 (Vβ11+GFP+) and compare their functional activity with purified cells expressing TCR only (Vβ11+GFP−; Figure 1D). Peptide titration revealed that TCR+CD3 cells produced higher levels of cytokines and were able to respond to lower peptide concentrations than TCR only cells (Figure 1E).

CD3 is rate limiting for TCR expression and function in primary murine T cells.

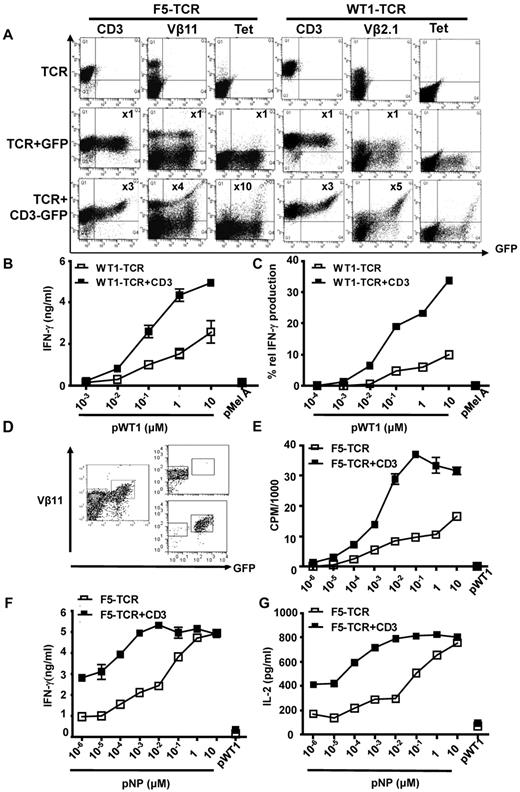

We next explored whether the observations made with the 58α−β− lymphoma cell line also applied to primary murine T cells. Magnetic beads were used to deplete C57BL/6 splenocytes of Vβ11+ T cells. Splenocytes were transduced with F5-TCR alone, or with F5-TCR together with CD3-GFP or a GFP control vector. Endogenous Vβ11 expression and H2Db/pNP tetramer staining were low in mock-transduced T cells (1.1% and 0.1% respectively; data not shown). After cotransduction of TCR and CD3-GFP the level of CD3 expression in the GFP+ cells was 3-fold greater than in the GFP-negative cells (Figure 2A). The increased level of CD3 expression was associated with a 4-fold increase in Vβ11 staining and a 10-fold increase in tetramer staining. No increase in CD3, Vβ11 and tetramer staining was seen when the F5-TCR was cotransduced with a GFP control vector, indicating that the introduced CD3 genes were required to achieve improved TCR expression (Figure 2A).

CD3 is rate limiting for expression and function of the F5-TCR and the WT1-TCR in primary T cells. (A) C57BL/6 splenocytes were Vβ11 depleted before activation and transduced with the F5-TCR, F5-TCR+control-GFP, or F5-TCR+CD3-GFP. Cells were stained with antibodies against Vβ11 or H2Db/pNP tetramer. Alternatively, total splenic T cells were transduced with the WT1-TCR, WT1-TCR+control-GFP, or WT1-TCR+CD3-GFP and stained with antibodies against CD3, Vβ2.1, or with HLA-A2/pWT126 tetramer. The numbers in the panels indicate the fold increase in the level of CD3 or TCR expression (measured by MFI) in cells expressing TCR+CD3-GFP or TCR+control-GFP (Q2) compared with the cells expressing TCR only (Q1). The data are representative of 5 performed experiments. (B) Bulk transduced T cells (1 × 106) were stimulated with 5 × 105 T2 cells loaded with increasing concentrations of pWT126 or 10μM pMelanA control peptide. Supernatant was harvested and assessed for IFNγ production by ELISA. The graph demonstrates the mean IFNγ concentration ± SD of triplicate values. The data are from one of 3 performed experiments. (C) Intracellular cytokine production was assessed in CD8+ T cells expressing WT1-TCR+CD3-GFP or WT1-TCR-only. Transduced T cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of pWT126 or 10μM pMelanA control peptide. The intracellular IFNγ staining was assessed in CD8+ T cells expressing TCR+CD3 or TCR-only (Vβ2.1+GFP+ cells and Vβ2.1+GFP− cells, respectively). The graph shows the percentage of Vβ2.1+GFP+ and Vβ2.1+GFP− T cells producing IFNγ. (D) CD8+ T cells from C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR+CD3-GFP and FACS purified to obtain cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3 (purity of 86%-96%, respectively). (E) F5-TCR or F5-TCR+CD3 T cells (1 × 105) were stimulated with 1 × 105 irradiated splenocytes coated with increasing concentrations of pNP or 10μM pWT126 control peptide, and peptide-specific proliferation was measured by thymidine incorporation. (F-G) 1 × 105 F5-TCR or TCR+CD3 T cells were stimulated with 1 × 105 irradiated splenocytes coated with increasing concentrations of pNP or 10μM pWT126 control peptide. Supernatant was harvested and assessed for (F) IFNγ and (G) IL-2 production by ELISA. The graph demonstrates the mean cytokine concentration ± SD of triplicate values. The data are from 2 performed experiments.

CD3 is rate limiting for expression and function of the F5-TCR and the WT1-TCR in primary T cells. (A) C57BL/6 splenocytes were Vβ11 depleted before activation and transduced with the F5-TCR, F5-TCR+control-GFP, or F5-TCR+CD3-GFP. Cells were stained with antibodies against Vβ11 or H2Db/pNP tetramer. Alternatively, total splenic T cells were transduced with the WT1-TCR, WT1-TCR+control-GFP, or WT1-TCR+CD3-GFP and stained with antibodies against CD3, Vβ2.1, or with HLA-A2/pWT126 tetramer. The numbers in the panels indicate the fold increase in the level of CD3 or TCR expression (measured by MFI) in cells expressing TCR+CD3-GFP or TCR+control-GFP (Q2) compared with the cells expressing TCR only (Q1). The data are representative of 5 performed experiments. (B) Bulk transduced T cells (1 × 106) were stimulated with 5 × 105 T2 cells loaded with increasing concentrations of pWT126 or 10μM pMelanA control peptide. Supernatant was harvested and assessed for IFNγ production by ELISA. The graph demonstrates the mean IFNγ concentration ± SD of triplicate values. The data are from one of 3 performed experiments. (C) Intracellular cytokine production was assessed in CD8+ T cells expressing WT1-TCR+CD3-GFP or WT1-TCR-only. Transduced T cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of pWT126 or 10μM pMelanA control peptide. The intracellular IFNγ staining was assessed in CD8+ T cells expressing TCR+CD3 or TCR-only (Vβ2.1+GFP+ cells and Vβ2.1+GFP− cells, respectively). The graph shows the percentage of Vβ2.1+GFP+ and Vβ2.1+GFP− T cells producing IFNγ. (D) CD8+ T cells from C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR+CD3-GFP and FACS purified to obtain cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3 (purity of 86%-96%, respectively). (E) F5-TCR or F5-TCR+CD3 T cells (1 × 105) were stimulated with 1 × 105 irradiated splenocytes coated with increasing concentrations of pNP or 10μM pWT126 control peptide, and peptide-specific proliferation was measured by thymidine incorporation. (F-G) 1 × 105 F5-TCR or TCR+CD3 T cells were stimulated with 1 × 105 irradiated splenocytes coated with increasing concentrations of pNP or 10μM pWT126 control peptide. Supernatant was harvested and assessed for (F) IFNγ and (G) IL-2 production by ELISA. The graph demonstrates the mean cytokine concentration ± SD of triplicate values. The data are from 2 performed experiments.

Similar results were seen when T cells were transduced with the WT1-TCR. Un-transduced murine T cells did not bind the anti-human Vβ2.1 antibody or the HLA-A2/pWT126 tetramer (data not shown). After transduction with the WT1-TCR alone, Vβ2.1-expression was readily detectable, although these cells did not bind tetramer (Figure 2A). In T cells that were co-transduced with the WT1-TCR and CD3-GFP the level of Vβ2.1 expression in GFP+ cells increased by 5-fold compared with GFP− cells. Furthermore, only the GFPbright T cells were able to bind HLA-A2/pWT126 tetramer (Figure 2A). Cells transduced with WT1-TCR and a GFP control vector demonstrated lack of tetramer staining of the GFPbright T cells. This indicated that CD3 gene expression from the CD3-GFP vector was essential to enhance expression of the introduced WT1-TCR to a level that was sufficient for binding of the HLA-A2/pWT126 tetramer.

Antigen-specific IFNγ production by WT1-TCR transduced T cells was examined after stimulation with human T2 cells loaded with decreasing concentrations of peptide antigen. At all peptide concentrations bulk T cells transduced with WT1-TCR and CD3-GFP produced more IFNγ than T cells transduced with the WT1-TCR alone (Figure 2B). We used intracellular cytokine staining and analyzed cytokine production in gated GFP+ T cells expressing introduced TCR+CD3 compared with the GFP− T cells expressing only TCR. This analysis revealed that at all peptide concentrations a greater percentage of TCR+GFP+ produced IFNγ compared with the percentage of responding TCR+GFP− cells (Figure 2C). At 10−2μM peptide concentration a clear response was seen in the TCR+GFP+ cells but not the TCR+GFP− cells. Together these data indicated that CD3 was rate limiting for TCR expression in primary T cells, and that the transfer of additional CD3 genes enhanced TCR expression and the functional avidity of gene-modified T cells.

Similar to the WT1-TCR data, the analysis of the F5-TCR suggested that bulk T cells transduced with CD3 and TCR were able to recognize lower concentration of peptide than the cells transduced with TCR-only (data not shown). We used flow cytometric sorting of bulk transduced T cells to perform functional experiments with purified TCR+CD3 and TCR-only cells (Figure 2D). Purified T cells were stimulated with antigen-presenting cells coated with decreasing concentrations of pNP to measure peptide-specific proliferation and cytokine production. At peptide concentrations < 10μM, TCR+CD3 T cells consistently displayed more proliferation, IFNγ and IL-2 production (Figure 2E-G). At a concentration of 10−5μM the TCR+CD3 T cells showed a proliferative response, while TCR-only T cells required 10-fold more peptide to trigger peptide-specific proliferation (Figure 2E). Cytokine production occurred at lower peptide concentrations than proliferation (compare Figure 2E with F,G). At low peptide concentrations the level of cytokine production of TCR+CD3 cells was superior to that of TCR-only cells, while similar cytokine production was seen at high peptide concentrations (Figure 2F-G).

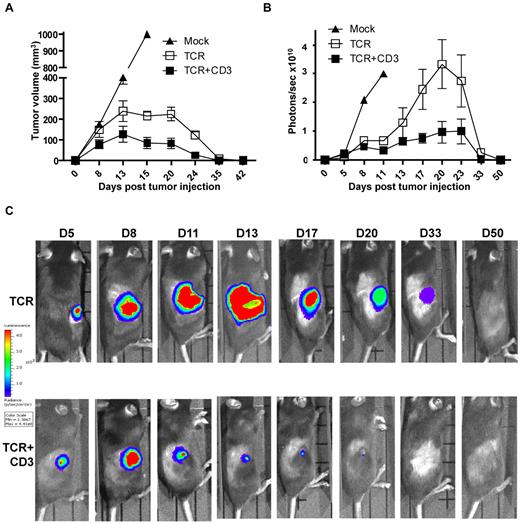

CD3 gene transfer enhances tumor elimination by TCR gene transduced T cells

We next explored whether the functional improvement observed in vitro correlated with improved T-cell function in vivo. C57BL/6 mice were challenged subcutaneously with 1 × 106 EL4.NP tumor cells, and the following day the mice were treated by intravenous transfer of 3 × 105 transduced CD8+ T cells. Tumor size was measured at the site of tumor injection at different time intervals. All mice demonstrated measurable tumor burden by day 8 (Figure 3A). In mice that received mock-transduced control CD8+ T cells the tumors grew progressively until day 15 when the animals were killed. In the groups that received CD8+ T cells transduced with TCR+CD3 or TCR-only, the tumor growth was controlled and mice were tumor-free at day 35-42 (Figure 3A). The data suggested that tumor size was smaller in mice treated with TCR+CD3 T cells. We performed experiments with luciferase-expressing EL4.NP tumor cells and used bioluminescence imaging to more accurately measure the tumor burden in the T cell treated mice (Figure 3B-C). Figure 3C shows the imaging of representative mice challenged with luciferase+ tumors, indicating that TCR+CD3 T cells limited tumor growth more efficiently than TCR-only T cells. A summary of the data showed that in mice treated with TCR+CD3 T cells tumors grew initially until day 8 after T-cell transfer, followed by a period of growth inhibition and subsequent tumor rejection (Figure 3B). In mice treated with TCR-only T cells, tumors continued to grow until day 20-23 followed by growth reduction and tumor rejection. These data indicated that provision of additional CD3 enhanced the ability of T cells to limit tumor growth in vivo, although it was not required to achieve tumor rejection at the dose of T cells and tumor cells used in this model.

TCR+CD3 co-transduction of T cells reduces tumor burden. (A) CD8+ T cells from Thy1.1+ C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR, F5-TCR+CD3-GFP, or left un-transduced (Mock). Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 mice were sublethally irradiated (5.5Gy) and injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0 followed by intravenous transfer of a total of 3 × 105 transduced Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells. Tumor volume was measured at the indicated time points. Data are from 3 experiments each with 3 mice/group. (B-C) CD8+ T cells from Thy1.1+ C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR, F5-TCR+CD3-GFP, or left untransduced (Mock). Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 mice were sublethally irradiated (5.5Gy) and injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 firefly luciferase-expressing EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0 followed by intravenous transfer of a total of 3 × 105 transduced CD8+ T cells the next day. Tumor growth was monitored by IVIS-100 bioluminescence camera. (B) Graph shows the mean bioluminescent signals in photons recorded at the site of tumor growth. (C) The bioluminescent signals at the site of tumor growth is shown over a 50 day period in representative mice treated with T cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3-GFP. Data in panels B and C are from 2 independent experiments each with 3 mice/group.

TCR+CD3 co-transduction of T cells reduces tumor burden. (A) CD8+ T cells from Thy1.1+ C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR, F5-TCR+CD3-GFP, or left un-transduced (Mock). Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 mice were sublethally irradiated (5.5Gy) and injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0 followed by intravenous transfer of a total of 3 × 105 transduced Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells. Tumor volume was measured at the indicated time points. Data are from 3 experiments each with 3 mice/group. (B-C) CD8+ T cells from Thy1.1+ C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR, F5-TCR+CD3-GFP, or left untransduced (Mock). Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 mice were sublethally irradiated (5.5Gy) and injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 firefly luciferase-expressing EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0 followed by intravenous transfer of a total of 3 × 105 transduced CD8+ T cells the next day. Tumor growth was monitored by IVIS-100 bioluminescence camera. (B) Graph shows the mean bioluminescent signals in photons recorded at the site of tumor growth. (C) The bioluminescent signals at the site of tumor growth is shown over a 50 day period in representative mice treated with T cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3-GFP. Data in panels B and C are from 2 independent experiments each with 3 mice/group.

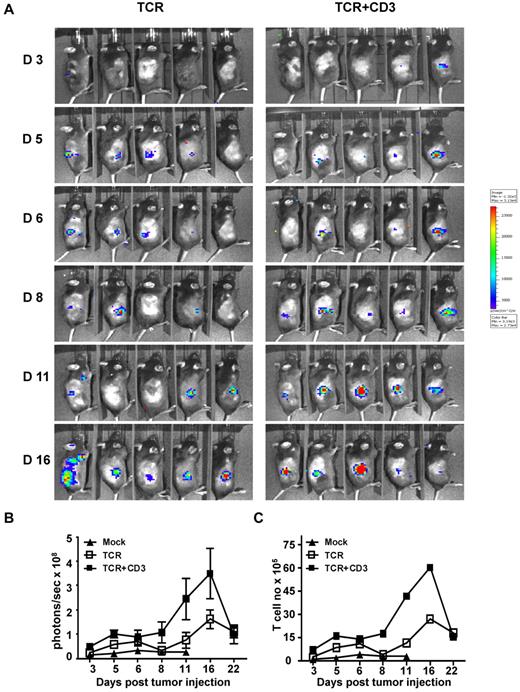

CD3 gene transfer enhances tumor infiltration and persistence of TCR gene transduced T cells in vivo

The possible reasons for the improved inhibition of tumor growth by TCR+CD3 gene modified T cells were explored. T cells from luciferase+ transgenic mice were used to image the migration and tumor site accumulation of gene modified T cells. C57Bl/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with luciferase-negative EL4.NP tumor cells followed by adoptive transfer of luciferase+ CD8+ T cells transduced with TCR+CD3 or TCR-only. Infiltration at the tumor site was visualized using bioluminescent imaging. T cells were detectable at the tumor site in the majority of mice at day 5 after intravenous cell transfer (Figure 4A). However, at day 11 the mice treated with TCR+CD3 T cells showed further T-cell accumulation at the tumor site, while the accumulation was less pronounced in mice treated with TCR-only T cells (Figure 4A-B). The conversion of the bioluminescent photon signal into cell numbers indicated that both TCR+CD3 and TCR-only T cells expanded in vivo because the number of tumor infiltrating T cells was > 10-fold greater than the number of injected T cells (Figure 4C). In the early phase of tumor rejection the accumulation of the TCR+CD3 T cells was at least double the number of TCR-only T cells, linking increased numbers of tumor-infiltrating T cells to more effective tumor cell elimination. Together, these experiments indicated that adoptively transferred T cells transduced with TCR+CD3 expanded in vivo more effectively and accumulated at the tumor site in larger numbers than T cells transduced with TCR-only.

TCR+CD3 co-transduction of T cells enhances tumor infiltration of T cells. Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells from firefly luciferase+ transgenic C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR or F5-TCR+CD3-GFP. Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 mice were sublethally irradiated (5.5 Gy) and injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0 followed by intravenous transfer of a total of 3 × 105 transduced luciferase+Thy1.1+ T cells the next day. (A) T-cell accumulation at the site of tumor growth was monitored by IVIS-100 bioluminescence camera at the indicated time points. (B) The graph shows the mean bioluminescent signals in photons/s in the groups of mice at the indicated time. (C) The photons/s were converted into number of accumulated T cells based on the bioluminescent signals obtained when titrated numbers of luciferase+ transgenic T cells were injected subcutaneously. Data are representative of 5 mice/group.

TCR+CD3 co-transduction of T cells enhances tumor infiltration of T cells. Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells from firefly luciferase+ transgenic C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR or F5-TCR+CD3-GFP. Thy1.2+ C57BL/6 mice were sublethally irradiated (5.5 Gy) and injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0 followed by intravenous transfer of a total of 3 × 105 transduced luciferase+Thy1.1+ T cells the next day. (A) T-cell accumulation at the site of tumor growth was monitored by IVIS-100 bioluminescence camera at the indicated time points. (B) The graph shows the mean bioluminescent signals in photons/s in the groups of mice at the indicated time. (C) The photons/s were converted into number of accumulated T cells based on the bioluminescent signals obtained when titrated numbers of luciferase+ transgenic T cells were injected subcutaneously. Data are representative of 5 mice/group.

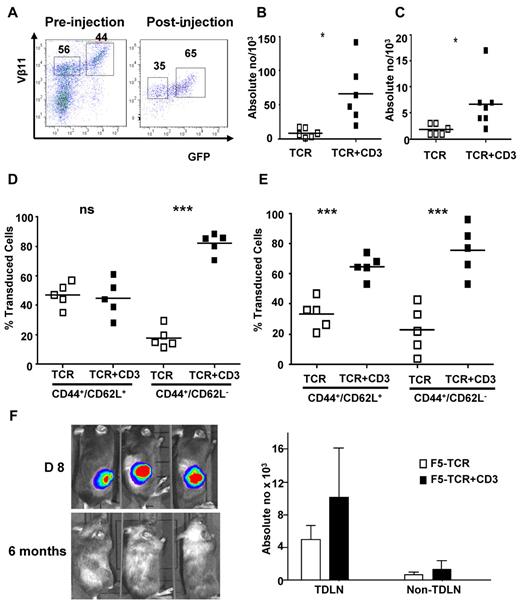

We next designed experiments to directly compare in the same animals the expansion and memory formation of T cells transduced with TCR+CD3 or TCR-only. Gene-modified CD8+ T cells were generated in vitro and mixed to obtain transduced populations containing similar proportions of TCR+CD3 and TCR-only T cells for adoptive transfer into tumor bearing mice (Figure 5A). At day 35 after T-cell transfer, when tumors were cleared, draining lymph nodes and spleen were collected. The analysis revealed that the absolute number of TCR+CD3 T cells was at least 3-fold higher than the number of TCR-only T cells in both spleen (Figure 5B) and lymph nodes (Figure 5C). We used CD62L and CD44 expression to identify central memory (CD62L+CD44+) and effector memory (CD62L−CD44+) T cells in spleen and tumor draining lymph nodes. In spleen, the central memory population contained similar percentages of TCR+CD3 and TCR-only T cells, whereas the effector memory compartment contained primarily TCR+CD3 T cells (Figure 5D). In contrast, in the tumor draining lymph nodes the TCR+CD3 T cells dominated both the central as well as effector memory T-cell compartment (Figure 5E). Together, these data indicated that TCR+CD3 T cells were more effective than TCR-only T cells in expanding in vivo and developing memory populations locally and systemically.

Preferential expansion of TCR+CD3 double transduced T cells in vivo. Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells from C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR or F5-TCR+CD3-GFP. Thy1.2+ recipient C57BL/6 mice were sublethally irradiated (5.5 Gy) and injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0. The next day, mice were intravenously injected with 3 × 105 transduced Thy1.1+ T cells containing similar numbers of F5-TCR and F5-TCR+CD3-GFP T cells. (A) FACS analysis of transduced T cells before injection and recovered from mice 35 days after injection. Dot plots are gated on Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells and the numbers indicate the percentage ofVβ11+ T cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3-GFP. (B-C) Absolute numbers of transduced cells recovered from the spleen (B) and tumor draining lymph nodes (TDLN; C) are shown. Cells from spleen (D) and TDLN (E) were stained with antibodies for CD44 and CD62L to identify central and effector memory phenotype T cells. Graphs show the relative frequency of TCR-only and TCR+CD3-GFP T cells in the central and effector memory compartment. Data are representative of 5 mice/group. (F) Thy1.2+ irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 firefly luciferase-expressing EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0, followed by treatment with 3 × 105 transduced Thy1.1+ T cells containing similar numbers of F5-TCR and F5-TCR+CD3-GFP cells. Mice were imaged before (day 8) and after tumor rejection (6 months). Tumor-free mice were rechallenged with 1 × 106 irradiated EL4.NP tumor cells injected in the lower leg. After 5 days, mice were killed and T cells were collected from TDLN and contra-lateral control LNs (nonTDLN). FACS analysis was performed to determine the number of transferred Thy1.1+ T cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3-GFP. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Preferential expansion of TCR+CD3 double transduced T cells in vivo. Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells from C57BL/6 mice were transduced with F5-TCR or F5-TCR+CD3-GFP. Thy1.2+ recipient C57BL/6 mice were sublethally irradiated (5.5 Gy) and injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0. The next day, mice were intravenously injected with 3 × 105 transduced Thy1.1+ T cells containing similar numbers of F5-TCR and F5-TCR+CD3-GFP T cells. (A) FACS analysis of transduced T cells before injection and recovered from mice 35 days after injection. Dot plots are gated on Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells and the numbers indicate the percentage ofVβ11+ T cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3-GFP. (B-C) Absolute numbers of transduced cells recovered from the spleen (B) and tumor draining lymph nodes (TDLN; C) are shown. Cells from spleen (D) and TDLN (E) were stained with antibodies for CD44 and CD62L to identify central and effector memory phenotype T cells. Graphs show the relative frequency of TCR-only and TCR+CD3-GFP T cells in the central and effector memory compartment. Data are representative of 5 mice/group. (F) Thy1.2+ irradiated C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 firefly luciferase-expressing EL4.NP tumor cells on day 0, followed by treatment with 3 × 105 transduced Thy1.1+ T cells containing similar numbers of F5-TCR and F5-TCR+CD3-GFP cells. Mice were imaged before (day 8) and after tumor rejection (6 months). Tumor-free mice were rechallenged with 1 × 106 irradiated EL4.NP tumor cells injected in the lower leg. After 5 days, mice were killed and T cells were collected from TDLN and contra-lateral control LNs (nonTDLN). FACS analysis was performed to determine the number of transferred Thy1.1+ T cells expressing TCR-only or TCR+CD3-GFP. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

We next compared the ability of TCR+CD3 T cells and TCR-only T cells to mount functional memory recall responses in vivo. For these experiments groups of tumor-challenged mice were treated with similar numbers of TCR+CD3 T cells and TCR-only T cells. At 6 months after T-cell transfer and tumor elimination (Figure 5F), mice were rechallenged with EL-4 tumor cells and the T-cell response was analyzed in the lymph nodes draining the tumor site and nondraining control lymph nodes. Figure 5F indicates that both TCR+CD3 and TCR-only T cells mounted a recall response and expanded in the draining lymph node compared with the control lymph node. However, the number of expanded TCR+CD3 T cells was higher than the number of TCR-only T cells, indicating that the former mounted a more effective memory recall response.

Discussion

TCR gene therapy offers the possibility to rapidly generate T-cell populations of defined antigen-specificity. Because functional T-cell avidity is in part dependent on high TCR expression, we explored whether TCR+CD3 transfer can enhance the level of TCR expression and therefore the functional avidity of gene modified T cells.

In vitro experiments indicated that TCR+CD3 gene modified T cells displayed improved responses on stimulation with limiting concentrations of antigen, which was associated with improved in vivo expansion of TCR+CD3 T cells after adoptive transfer into tumor-bearing mice. Compared with TCR-only T cells, TCR+CD3 T cells accumulated in tumors more rapidly and in greater numbers, which resulted in more effective control of tumor growth. In contrast, TCR-only T cells accumulated more slowly and allowed a period of continued tumor growth before sufficient “immunity” was established to achieve tumor rejection. It is likely that more effective “immunity” by TCR+CD3 T cells is not only related to the accumulation of larger numbers of T cells, but also to enhanced effector function per cell, as indicated by in vitro cytokine production assays comparing TCR+CD3 T cells and TCR-only cells.

The adoptive transfer of similar numbers of TCR+CD3 and TCR-only T cells demonstrated directly the preferential expansion of the “high avidity” TCR+CD3 T cells in vivo. This is similar to the observations with high and low avidity transgenic T cells expressing high and low levels of the same transgenic TCR.13,27 In this system, primary in vivo T-cell responses were dominated by the high avidity, TCR-high T cells at the expense of the TCR-low cells. In our system, the T cells were fully activated during the retroviral transduction protocol before T-cell transfer. Our experiments show that the level of TCR expression determined the efficacy of fully activated T cells to protect against tumor growth and to develop into functional memory cells.

Previous studies showed that priming of naive T cells was associated with up-regulation of the lck tyrosine kinase, a key molecule required for signal transduction via the TCR.28 The lck up-regulation was associated with “affinity maturation” of the activated T cells, enabling them to respond to lower concentration of antigen compared with naive T cells. We show that the additional up-regulation of TCR expression results in further “affinity maturation” of activated T cells. It is likely that up-regulation of both TCR and lck is required to achieve optimal antigen recognition and signal transduction for the triggering of antigen-specific T-cell responses.

The mis-pairing of introduced TCR chains with endogenous chains can generate “novel” TCR specificities that can be directed against normal self-antigens which resulted in “autoimmune” attack when TCR gene modified T cells were adoptively transferred into syngeneic mice.29 In contrast, trials in cancer patients have not revealed toxicity because of TCR mis-pairing.30 Although we have not seen toxicity when TCR+CD3 T cells were adoptively transferred into recipient mice, it is possible that the enhanced TCR expression may increase the expression levels of mis-paired, potentially auto-reactive TCR. This risk can be reduced by the use of “strong” TCR that preferentially pair with each other and show little mis-pairing with endogenous TCR.31,32 In this study we used TCR constructs that were codon optimized and contained an additional disulphide bond in the constant region, both of which has been shown in the past to generate “strong” TCR that were efficiently expressed in transduced primary T cells and completely suppressed the surface expression of endogenous TCR.33 The up-regulation of CD3 in the gene-modified T cells is likely to favor the introduced TCR over the endogenous TCR because of higher RNA expression from the retroviral vector and more efficient pairing of the modified TCR chains.

We propose that up-regulation of CD3 and TCR expression is a reliable strategy to improve the avidity of TCR gene modified T cells. Affinity maturation of TCR molecules using yeast display, phage display and site directed mutagenesis has been developed as an alternative strategy to enhance the functional avidity of TCR gene modified T cells.34-36 However, these approaches alter the fine specificity of the TCR molecules and can result in enhanced cross reactivity resulting in nonantigen specific effector function when the modified TCR were tested in gene modified T cells.37 Paradoxically, in some experiments T cells expressing affinity matured TCR displayed lower functional avidity than T cells expressing wild type TCR.36 In fact, we have recently observed that T cells expressing affinity matured TCR with long binding half life for MHC/peptide triggered fast effector function but displayed reduced functional avidity and were unable to recognize low concentration of antigen. This is most likely related to the requirement for serial TCR triggering for recognition of low dose of antigen, which is disrupted when the half-life of TCR-MHC/peptide binding is artificially increased by modifying TCR sequences. Hence, the up-regulation of wild type TCR is a more reliable strategy to enhance the avidity of TCR gene modified T cells.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Leukemia and Lymphoma Research, Experimental Cancer Medicine Center, ATTACK EU Consortium, MRC, and Dinwoodie Settlement Charitable Trust.

Authorship

Contribution: H.J.S., M.A., and J.W.K. designed experiments; M.A., J.W.K., S.A.X., C.V., A.H., and G.P. performed experiments; M.A., J.W.K., J.W., E.M., and H.J.S. analyzed data; and M.A., J.W.K., and H.J.S. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.J.S. is a consultant for Cell Medica. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hans Stauss, Dept of Immunology, UCL Medical School, Royal Free Hospital, Rowland Hill Street, London NW3 2PF, United Kingdom; e-mail: h.stauss@ucl.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

M.A. and J.W.K. contributed equally to this article.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal