Abstract

Last year marked 30 years of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a curative treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Initially studies used stem cells from identical twins but techniques rapidly developed to use cells first from HLA-identical siblings and later unrelated donors. During the 1990s CML became the most frequent indication for allogeneic transplantation worldwide. This, together with the relative biologic homogeneity of CML in chronic phase, its responsiveness to graft-versus-leukemia effect and the ability to monitor low level residual disease placed CML at the forefront of research into different strategies of stem cell transplantation. The introduction of BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors during the last decade resulted in long-term disease control in the majority of patients with CML. In those who fail to respond and/or develop intolerance to these agents, transplantation remains an effective therapeutic solution. The combination of tyrosine kinase inhibitors with transplantation is an exciting new strategy and it provides inspiration for similar approaches in other malignancies.

Introduction

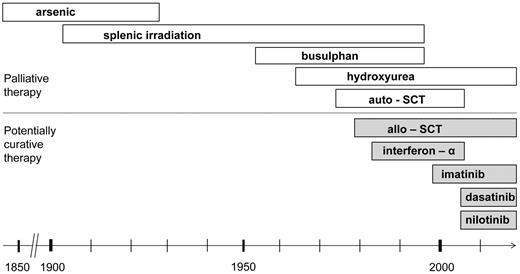

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) was the first leukemia described and the first to be characterized by a consistent chromosomal aberration, the 22q− or Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome. Early descriptions of therapy included the use of arsenic and radiotherapy, introduced at the beginning of the 20th century (Figure 1).1 One of the earliest randomized clinical studies in leukemia, published in 1968, showed radiotherapy to be inferior to chemotherapy with busulfan.2 Radiotherapy and later chemotherapy could control the signs and symptoms of CML in chronic phase, but could not prevent its inevitable transformation into a rapidly fatal chemoresistant blastic disease. The first treatment that eradicated the Ph-positive clone and induced cure was bone marrow transplantation, initially described in syngeneic twins. The first report of this approach, published more then 30 years ago,3 was soon followed by those describing the use of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched siblings4-7 and, later, of unrelated donors.8,9

Evolution of therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia. The first leukemia described and the first to be characterized by the consistent chromosomal aberration, 22q or Ph chromosome.

Evolution of therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia. The first leukemia described and the first to be characterized by the consistent chromosomal aberration, 22q or Ph chromosome.

Interestingly, before patients with CML became recipients of hematopoietic stem cells, they functioned as donors. The high circulating leukocyte counts in newly diagnosed patients encouraged the use of these cells to replace granulocytes in patients with treatment-induced aplasia. Observers noted that the CML cells were able to engraft temporarily10 and even change the blood group of the recipient, suggesting the presence of cells with engraftment potential in the peripheral blood.11 In addition these infusions caused a graft-versus-host reaction12 and it is now more than 40 years since Graw et al13 described an allogeneic graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect with the disappearance of leukemia blasts after infusion of leukocytes from a CML donor into a patient with acute leukemia and intractable infection.13

We review in this study the knowledge gained from transplantation in CML that furthered our understanding of leukemia, improved awareness of stem cell biology and immunotherapeutics, and initiated the concept of molecular monitoring and management of minimal residual disease. Many of the lessons learned in CML were later applied with good effect in various other diseases.

Autologous transplantation

The knowledge that cells derived from the patients' own bone marrow could successfully rescue hematopoiesis after high dose chemoradiotherapy,14 combined with improved techniques of human bone marrow cryopreservation in dimethylsulfoxide,15 led to treatment of CML in blast crisis by autologous transplantation. Investigators in Seattle reported results in 2 patients in 197416 and an additional 5 patients in 1978.17 Although the blasts disappeared in all patients, complete and prompt reestablishment of chronic phase was achieved only in 2 patients.

The results of clonogenic assays for hematopoietic progenitors in the blood of CML patients suggested that their blood might also contain cells with marrow repopulating capacity. There were in fact very large numbers of colony-forming granulocyte-macrophage forming units in the peripheral blood of untreated CML patients.18 Initial reports of treating 6 patients in blastic phase with high dose therapy followed by an infusion of nucleated cells collected and cryopreserved earlier in the disease, described complete restoration of chronic phase in 4 patients and partial restoration in 1 patient.19 The success of this approach in prolonging survival of patients in blast phase20 led to the practice of routine collection and storage of chronic phase cells in all newly diagnosed patients with CML in chronic phase.21

At the same time there were sporadic reports that patients who had been rendered pancytopenic by treatment with busulfan regenerated Ph-negative hematopoiesis that suggested residual normal hematopoietic cells may be present in bone marrow of at least some CML at diagnosis.22,23 Chervenick et al24 later observed that Ph-negative colonies could be grown from the bone marrow of patients at diagnosis. Furthermore, Cunningham et al25 demonstrated that intensive chemotherapy after splenectomy in patients with CML in chronic phase could result in the temporary restoration of Ph-negative hematopoiesis and consequent improved survival. In 1984, Dubé and colleagues26 reported that Ph-negative cells predominated in long-term cultures seeded with cells derived from patients with Ph-positive CML and suggested differences in the survival capacity of normal and leukemic cells in culture in vitro. Investigators in Baltimore were the first to collect Ph-negative peripheral stem cells after intensive chemotherapy in a patient in chronic phase and to use them later for autografting after blast transformation. The patient regenerated Ph-negative bone marrow but died of toxicity.27 Carella et al28 demonstrated that Ph-negative stem cells could also be collected shortly after high dose therapy of patients in blast phase and successfully used after subsequent autologous transplantation.

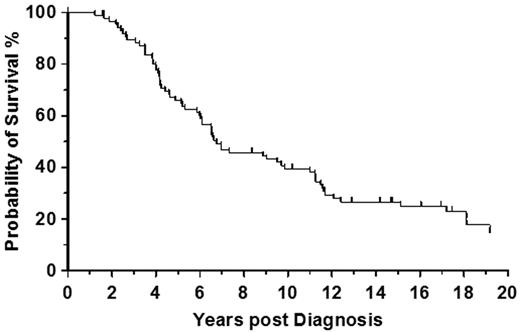

The reported survival advantage supported autologous hematopoietic transplantation of patients in chronic phase who were unsuitable for allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT).29 In our own institution we autografted a total of 87 patients in chronic phase with a median survival of 6.75 years (Figure 2). Although the autografting experience was crucial for understanding the biology of CML its precise clinical impact remains unclear. Initial enthusiasm for randomized trials of autografting versus conventional therapy, which were initiated in late 1990s waned after the introduction of BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) into clinical practice. Subsequently the rates of autografts decreased dramatically. Despite this decline, there is now the potential to combine autografting with second generation TKI (2G-TKI) in imatinib-resistant patients.30

Autologous transplantation in chronic phase CML. Survival rate from diagnosis in 87 patients autografted at the Hammersmith Hospital, London, for CML in first chronic phase.

Autologous transplantation in chronic phase CML. Survival rate from diagnosis in 87 patients autografted at the Hammersmith Hospital, London, for CML in first chronic phase.

The rise of allogeneic transplantation and the development of donor registries

The initial results of allo-SCT for leukemia in general and CML in particular were disappointing.31-34 Although the leukemia initially disappeared in the majority of patients who underwent transplantation, it was associated with both high nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and high relapse rates, now known to be related to delaying transplantation until the advanced stages of disease. Improvements in survival came only when transplantation was performed in the chronic phase. The first 4 patients who underwent transplantation with bone marrow from their identical twins were reported to be clinically well and in cytogenetic remission 22 to 31 months later.3 From these excellent results, investigators moved to using HLA-identical sibling donors.4-7 The reported outcomes were also encouraging, even in patients who were in accelerated phase before allografting.35 Data of 138 patients with CML who underwent transplantation between 1978 and 1982 and reported to the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry showed 3-year survivals of 63%, 56%, and 16% for patients who underwent transplantation in the chronic, accelerated, and blast phase, respectively. Only 2 of 29 patients (7%) who underwent transplantation in the chronic phase relapsed.36

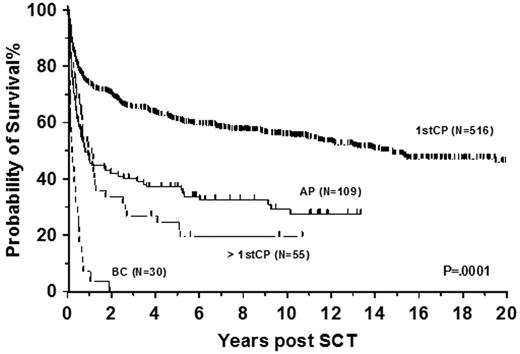

The effect of disease phase on the outcome of transplantation has not changed over the years (Figure 3). In particular patients who underwent transplantation in blast phase have an extremely poor prognosis and one of the few downsides of TKI therapy is that patients are now coming to transplantation only after disease progression. To optimize the effect of allo-SCT a second chronic phase should be achieved using TKI or conventional combination chemotherapy.37 Additionally better leukemia-free survival (LFS) was observed in patients who underwent transplantation within 1-year of diagnosis,38 and time to transplantation remains a prognostic factor even in the era of interferon-α (INF-α)39 and imatinib.40

Allogeneic transplantation in CML. Data shows survival from diagnosis of 710 patients allografted at Hammersmith Hospital, London, for CML between 1981 and 2010. Patients who underwent transplantation in first chronic phase (1stCP) had the best survival, followed by patients who underwent transplantation in accelerated phase (AP), patients who underwent transplantation in more than first chronic phase (> 1stCP), and patients allografted in blast crisis (BC).

Allogeneic transplantation in CML. Data shows survival from diagnosis of 710 patients allografted at Hammersmith Hospital, London, for CML between 1981 and 2010. Patients who underwent transplantation in first chronic phase (1stCP) had the best survival, followed by patients who underwent transplantation in accelerated phase (AP), patients who underwent transplantation in more than first chronic phase (> 1stCP), and patients allografted in blast crisis (BC).

Only 30% to 35% of patients who could benefit from allo-SCT have an HLA-identical family donor and this percentage will decrease as family sizes get smaller. Alternative donor transplantations were therefore attempted for otherwise fatal diseases. Investigators in London performed the first HLA-matched bone marrow transplantation from a volunteer unrelated donor to produce an engrafted survivor in April 1973. The recipient was a child with chronic granulomatous disease who achieved a partial chimerism lasting 6 years.41,42 As the use of HLA-matched unrelated donors appeared feasible, efforts to establish registries of HLA typed volunteer unrelated donors commenced, the first of these being the Anthony Nolan Trust in London.43

In adults, the first successful results of unrelated allo-SCT were reported in 1980 by the Seattle group for acute leukemia44 and by our group for aplastic anemia and CML.8,45,46 Further development of the unrelated donor registries during the 1980s led to expansion of transplantation with CML becoming the commonest indication throughout the world.47 With the introduction of high resolution HLA typing, the outcomes of allografting using stem cells from matched unrelated donors are comparable with those of HLA-matched siblings,48 although larger registry studies still indicate the best outcomes with matched sibling donors, followed by matched unrelated, then single and a double antigen mismatched unrelated donors.40,49

Currently it is possible to find a matched unrelated donor for the majority of white patients, though not for patients from ethnic minorities. However the development of cord blood registries has increased the chances of finding a suitable donor for these patients. The results of both related and unrelated cord blood allografts for CML are encouraging in children, but experience in adults remains limited even 15 years after the first successful cord blood transplantation for CML.50 Investigators in Valencia recently reported 26 adults with CML of whom only 7 were in the first chronic phase at the time of a single-unit transplantation. NRM was 41% for patients who underwent transplantation in chronic phase, but all 8 patients who underwent transplantation in advanced phase died. There were no relapses, and the LFS after a median follow-up of 8 years was 41%.51 A Japanese registry study reported outcomes in 86 patients with CML whose median age was 39 years (9 patients < 16 years, 19 patients > 50 years). Overall survival and LFS were 53% and 38%, respectively.52

Graft-versus-host disease and effects of T-cell depletion

The major causes of morbidity and mortality during the early allo-SCT period were infections and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). The first successful prevention of GVHD was achieved by posttransplantation immunosuppression with methotrexate and later with cyclosporine. In patients with CML, the combination of both drugs gave good protection against GVHD without a significant increase in relapse53 and subsequently became a standard prophylactic regimen in most transplant centers.

The 1980s saw the introduction of T-cell depletion, first achieved by treating bone marrow in vitro with monoclonal antibodies54-56 and later by other in vitro techniques.57 This approach was effective in decreasing both the severity and frequency of GVHD, but was associated with a significantly higher frequency of graft failure.56 This was later overcome by increasing the intensity or immunosuppressive efficacy of conditioning, most elegantly achieved by the pretransplantation in vivo use of the same anti–T-cell antibodies that were used for T-cell depletion of the graft.58 Unfortunately the widespread application of T-cell depletion soon revealed an increased relapse rate, which first became apparent in patients who underwent transplantation for CML.59

This clinical observation was important and confirmed results previously reported in animal models. An antitumor effect of bone marrow transplantation not explained by pretransplantation radiotherapy was first observed by investigators at the UK Medical Research Council laboratories in a murine model in 1956,61 but conclusive evidence of this phenomenon in humans was lacking. After the initial report from Graw et al,13 Odom et al60 reported 2 patients whose acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapsed after allogeneic transplantation but disappeared at the onset of GVHD.61 Subsequently, investigators in Seattle published a series on patients who underwent transplantation for acute leukemia, where an increased probability of being in remission was associated with grade 2-4 acute, or any degree of chronic, GVHD.62 The increased rate of relapse after T-cell depletion was more obvious in chronic phase CML than in other malignancies63 and it provided direct evidence of the T-cell–mediated GVL effect of allo-SCT. The observation of an increased relapse rate in recipients of cells from identical twins compared with HLA-matched siblings further supported the GVL hypothesis.63-65

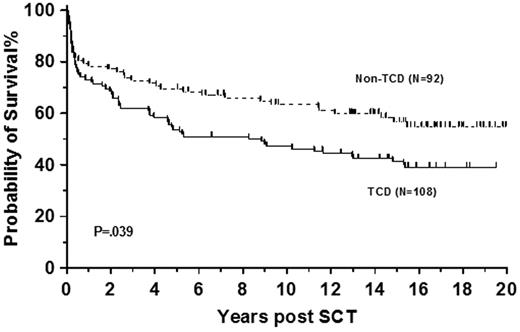

The increase in relapse rate led to our discontinuation of T-cell depletion in sibling allografts for CML in 1995 (Figure 4). Others continued with its use and reported good outcomes in sibling transplantations particularly after the introduction of donor lymphocyte infusions (DLI).66,67 We continued in vivo T-cell depletion in recipients of unrelated donor cells and reported a 5-year survival of 53% with probability of developing severe acute GVHD (grade 3 or 4) of 15%.68 As T-cell depletion delays immune reconstitution, infections are more common57 and CMV serostatus is a significant predictor of overall survival with this transplantation technique.68 Although use of T-cell depletion in unrelated allo-SCT showed shorter hospital stay and increased cost effectiveness compared with non–T-cell–depleted transplantations,69 a clear survival advantage of this approach in CML has never been demonstrated.

T-cell depletion in sibling allografts. Survival of 200 patients allografted at Hammersmith Hospital, London, before 1995 for CML in first chronic phase using sibling donor stratified by use of T-cell depletion. Patients who received T-cell–replete grafts (Non-TCD) had better survival than recipients of T-cell–depleted (TCD) allografts.

T-cell depletion in sibling allografts. Survival of 200 patients allografted at Hammersmith Hospital, London, before 1995 for CML in first chronic phase using sibling donor stratified by use of T-cell depletion. Patients who received T-cell–replete grafts (Non-TCD) had better survival than recipients of T-cell–depleted (TCD) allografts.

Donor lymphocyte infusions

Until the advent of T-cell depletion, relapse after allo-SCT for chronic phase disease was rare, but the outcome poor as treatment with INF-α was ineffective in the long-term and retransplantation was associated with high mortality. The use of additional donor lymphocytes at the time of relapse to restore remission completely changed this outcome.70,71 This was also proof of principle of the absolute efficacy of immune mechanisms in playing a vital role in curing leukemia.

Administration of DLI can reinduce remission in 60% to 90% of patients with CML who underwent transplantation in, and relapsed in, chronic phase. The use of escalating doses (Table 1) in case of persistent disease limits the risks for GVHD.72,73 A European study showed a 69% 5-year survival in 328 of patients who received DLI for relapsed CML. DLI-related mortality was 11% and disease-related mortality was 20%. Some form of GVHD was observed in 38% of patients. Risk factors for developing GVHD after DLI were T-cell dose at first DLI, time interval from transplantation to DLI, and donor type. In a time-dependent multivariate analysis, GVHD after DLI was associated with a risk of death of 2.3-fold compared with patients without GVHD.74

Escalating doses of donor lymphocytes for CML

| Dose . | Donor lymphocytes, CD3+ cells/kg . | |

|---|---|---|

| Sibling . | Unrelated . | |

| First | 5 × 106 | 106 |

| Second | 107 | 5 × 106 |

| Third | 5 × 107 | 107 |

| Fourth | 108 | 5 × 107 |

| Fifth | > 108 | 108 |

| Dose . | Donor lymphocytes, CD3+ cells/kg . | |

|---|---|---|

| Sibling . | Unrelated . | |

| First | 5 × 106 | 106 |

| Second | 107 | 5 × 106 |

| Third | 5 × 107 | 107 |

| Fourth | 108 | 5 × 107 |

| Fifth | > 108 | 108 |

Treatment dose used from sibling and unrelated cells in CML.

Interestingly the introduction of DLI necessitated the development of new statistical methods. As the majority of relapsed patients could re-enter remission, the method of calculation of LFS requires revision. One possible solution is the use of “current LFS” defined as the probability that a patient is alive and in remission at a given time after transplantation.75

Minimal residual disease monitoring

The observation that the disappearance of the Ph chromosome is associated with long-term survival in patients with CML led to strategies to define the fate of the leukemic clone after allo-SCT. In the 1980s, conventional cytogenetics was the principal technique for detection of residual leukemia after any treatment, including transplantation. Its sensitivity was low such that its clinical relevance was limited. The value of measuring minimal residual disease only became clear after implementation of techniques based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR).76 Early technology was qualitative in nature but was useful in identifying early relapse.77 Modern quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR78 has enabled the identification of early molecular relapse and the reliable prediction of cytogenetic and hematologic disease.79 The technique, further sophisticated through real-time quantitative equipment,80 has become a standard tool for monitoring of CML responses to allo-SCT and TKI. Having proved the usefulness of minimal residual disease detection, this technology was subsequently applied with great effect in many other malignant diseases.

Many CML patients will remain PCR-positive during the first 3 months after allo-SCT especially in the era of reduced intensity preparative regimens. In patients who are at least 4 months beyond allo-SCT, we define molecular relapse as follows: (1) BCR-ABL/ABL1 ratio higher than 0.02% in 3 samples a minimum of 4 weeks apart, or (2) clearly rising BCR-ABL/ABL1 ratio in 3 samples a minimum of 4 weeks apart with the last 2 higher than 0.02%, or (3) BCR-ABL/ABL1 ratio higher than 0.05% in 2 samples a minimum of 4 weeks apart.81 PCR values are not currently transferable between laboratories, but this procedure is the subject of a global collaboration to implement standardization of molecular monitoring.82

Mechanisms of GVL effect

Relative susceptibility of CML to DLI and reliability of minimal residual disease monitoring made CML an ideal model to study GVL mechanisms. CML is also unique in having differentiated leukemia-derived antigen presenting cells that can directly stimulate the donor immune system.

Absence of GVHD after successful DLI and occasional relapses in patients with GVHD suggested that GVL and GVHD mechanisms may not be identical. Falkenburg et al83 reported a successful treatment with leukemia-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) lines in a CML patient who relapsed in accelerated phase after allo-SCT and did not respond to DLI despite developing an acute and persistent chronic GVHD. T cells were isolated from the HLA-identical donor of the patient, selected on the ability of the cells to inhibit the in vitro growth of CML progenitor cells, and subsequently expanded in vitro to generate 3 CTL lines. After the infusion of CTL, the patient achieved a complete molecular response without acute but with worsening of the preexisting chronic GVHD. Although the antigens responsible for the GVL effect were not known, this report demonstrates a curative potential of adoptive immunotherapy.83

The first identified antigen for CTL on CML cells was PR1, a peptide derived from proteinase 3, a myeloid tissue restricted enzyme overexpressed in leukemia cells.84 A strong correlation between the presence of PR1-specific T cells in CML patients and clinical responses after treatment with INF-α and allo-SCT provided for the first time direct laboratory evidence of GVL.85 T-cell–mediated GVL requires the presence of either leukemia or hematopoietic cell specific antigens, or antigens of the minor histocompatibility system. The latter can also initiate GVHD. In CML the minor histocompatibility antigens show similar expression in all CD34+ subpopulations, whereas the expression of PR1, WT1, and PRAME differed between chronic and advanced phase as well as between primitive and more advanced subpopulations of CD34+ cells.86 The presence of T-cell clones targeting antigens expressed on the most primitive and quiescent leukemic CD34+ cell subpopulation, the leukemic stem cells, is responsible for elimination of leukemia. With allo-SCT the majority of patients achieve long-term molecular remissions,81 seen only very rarely with TKI therapy87 because of leukemic stem cell resistance to both imatinib and 2G-TKI.88,89

The lessons learned from studying GVL effects were applied in studies of cancer vaccines, which in turn potentially could be combined with allo-SCT.90

Assessment of the transplantation risk

A clear benefit of allo-SCT is that it can provide a cure in otherwise lethal disorders. A clear disadvantage is its association with considerable morbidity and mortality that typically occur early after procedure. Outcome can be improved by better selection of those most likely to benefit. In this context the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) developed a risk score system for patients with CML, the most frequent indication for an allo-SCT at that time. The EBMT score is based on 5 variables: donor type, disease phase, recipient age, donor/recipient sex combination, and interval from diagnosis to transplantation.39 As the variable of disease phase resulted in higher relative risks than other variables in the model,39 Passweg et al91 attempted to modify the score for patients in chronic phase for whom the decision of transplantation is most difficult. They found only one parameter with additional prognostic value, the Karnofsky performance score, but after inclusion the improvement over the original EBMT score was minimal.91 More recently reports of the effect of comorbidities on transplantation outcome92 prompted us to investigate the prognostic value of the hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index together with preconditioning levels of C-reactive protein in patients with CML in first chronic phase. We demonstrated that both C-reactive protein level less than 10 mg/L (regardless of infective status) and absence of comorbidities are independent predictors of NRM and survival.93

A modified EBMT score was more recently evaluated for prediction of transplantation outcomes in a range of hematologic diseases. In a retrospective study of 56 605 patients it predicted both overall survival and NRM in patients with acute and chronic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and aplastic anemia who underwent myeloablative or reduced intensity conditioned allo-SCT.94 Use of this simple tool, complemented with some other pretransplantation patient characteristics such as the comorbidity score92 in conjunction with donor availability is becoming very helpful in balancing the risks and benefits for transplantation against alternative treatment strategies.

Reduced intensity conditioning

Recognizing that much of the curative effect of allo-SCT was a result of the alloimmune effect has led to the development of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens.95,96 This has enabled transplantation with older patients and those with comorbidities. Retrospective comparisons of the outcome of myeloablative and reduced intensity approaches are always confounded by the fact that the 2-patient groups are not matched for factors (such as age, disease, or comorbidity) that are likely to affect the outcome directly. In CML an early attempt at a retrospective study showed a reduction in the early treatment mortality. However, it failed to demonstrate significantly improved 3-year survivals in patients with EBMT scores of 0 to 2, though overall sursvival was improved in patients with scores of 3 to 5.97

Although RIC approaches with preemptive (based on chimerism) or early (based on molecular monitoring of MRD) use of DLI might have been predicted to be most effective in CML, the advent of the TKI prevented randomized studies of RIC versus myeloablative conditioning. However, the introduction of TKI has offered new possibilities for combinations of RIC regimens, TKI and cellular immunotherapy as TKI acts synergically with DLI.98 One example of this experimental approach described 22 patients who were transplanted using a RIC regimen with in vivo T-cell depletion with alemtuzumab. Imatinib was commenced at engraftment and continued for 12 months. After this time, any patient with residual or recurrent disease was treated with DLI. This strategy reduced significantly the toxicity of DLI with 19 patients alive and 15 patients in molecular remission at 36 months after transplantation.99 A similar strategy is currently being investigated in patients with acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes with administration of azacitidine after engraftment.100

Current role of transplantation in CML

The last decade has been spent trying to determine the place of SCT in the modern management of CML. The introduction of imatinib into clinical practice led to a decrease in allo-SCT for CML rates in countries with high gross national income per capita even before any studies of imatinib had demonstrated a positive impact on survival, and this trend understandably persisted after the data became available.49 However in this era of TKI, the role of SCT is now different in patients in chronic phase and those who have progressed to more the advanced phase, with or without prior treatment with a TKI.

Patients in chronic phase

With longer follow-up of the imatinib trials and consequently more reliable data, the overall survival of patients who present in chronic phase exceeds 95% at 2 years and 80% to 90% at 5 years, and the 5-year probability of remaining in major cytogenetic response is approximately 60% to 65%.87,101 This remarkable effect, achieved with little toxicity, justifies the use of imatinib as first line treatment in all patients with newly diagnosed CML in chronic phase, although some controversy continues for children with a syngeneic or HLA-matched sibling donor. However, it is important to monitor disease response closely and to switch to second line treatment if there is evidence of treatment failure102 as defined by the European LeukemiaNet consensus opinion.103

For patients who fail imatinib and require a change of therapy, the choices include increasing the dose of imatinib, treatment with one of the 2G-TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib), or allo-SCT. To establish the next best therapeutic strategy, it is important to identify the cause of imatinib failure. In particular, detection of BCR-ABL-1 kinase domain mutations may determine the choice of 2G-TKI and in the case of the T315I mutation, which is associated with resistance to all the above mentioned drugs, a need for transplantation or experimental treatment.103 The rate of complete cytogenetic response to nilotinib or dasatinib is of the order of 40% to 45% suggesting that the majority of patients with imatinib resistance will require third-line therapy. Consideration should therefore be given to HLA typing and donor identification in younger patients at the time of imatinib failure so that transplantation can be performed without delay (and risk of disease progression) in patients failing to achieve cytogenetic responses on second-line therapy.

Recent studies have addressed the probability of response to treatment with 2G-TKI in patients who fail imatinib therapy. Our group has devised a scoring system that can predict responses to dasatinib or nilotinib based on factors known before commencing these drugs: Sokal score at diagnosis, best cytogenetic response to imatinib, and recurrent neutropenia on imatinib.101 Patients who are unlikely to respond to the 2G-TKI should be considered for transplantation. No prognostic score is perfect and therefore a trial of dasatinib or nilotinib, perhaps while awaiting donor results, is recommended. Investigators in Houston and our own group have reported that the level of cytogenetic response at 3 or 6 months after starting dasatinib or nilotinib predicts the probability of a major cytogenetic response at 1 year.104,105 Patients who fail 2G-TKI should always be considered for transplantation because the chances of a sustained response to another TKI are negligible. Garg et al106 observed that only 3 of 37 patients achieved complete cytogenetic remission and only 2 of them had a sustained response lasting 20 and 24 months.

Patients in advanced phase

The outcome of patients who present in blast phase or who progress while on therapy is poor. Allo-SCT is the only possible curative treatment but cures less than 10% of patients transplanted in frank blast crisis.107 Every effort should be made to restore a second chronic phase with acute myeloid leukemia–like chemotherapy or a 2G-TKI before proceeding to transplantation. Patients, presenting in accelerated phase are a rather heterogeneous group ranging from those with only slightly more advanced disease than chronic phase to those who are nearly in blast phase. Patients with less advanced disease may achieve relatively good results with TKI and should be treated similarly to patients with chronic phase. On the other hand, patients who are nearly in blast phase should be treated aggressively and considered for early allo-SCT. Unfortunately our prognostic biomarkers are not sufficiently developed to allow easy distinction of patients with varying prognoses. Progression to accelerated phase on imatinib is invariably associated with a poor prognosis and allo-SCT should be considered without delay.

Recent results of allogeneic transplantation

The outcome of allo-SCT for CML has steadily improved over time. EBMT registry data showed that the overall survival at 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years was 50%, 44%, 39%, 34%, and 32%, respectively, for patients who underwent transplantation in 1980s but had improved to 61% at 2 years for those who underwent transplantation between 2000 and 2003. Separate analysis of patients who underwent transplantation in the first chronic phase and those with more advanced disease reveals a remarkable improvement of survival in the former compared with the latter. Probabilities of 2-year survival of patients who underwent transplantation in the first chronic phase during the 1980s, 1990s, and between years 2000 and 2003 were 59%, 66%, and 70%, respectively, whereas survival of patients in accelerated phase or second (and subsequent) chronic phase was 40% to 47%. Furthermore, survival of patients undergoing transplantation in blast phase has not changed at 16% to 22%.49 On behalf of investigators at the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research, Lee et al40 analyzed the outcome of transplantation in 1309 patients treated between 1999 and 2004. The 3-year survival rate of patients who underwent transplantation with or without prior imatinib was 72% and 65% in chronic phase and 34% and 36% in advanced phase. This suggests that prior treatment with imatinib does not adversely affect transplantation outcome.

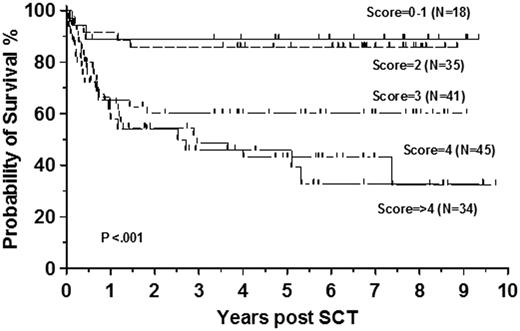

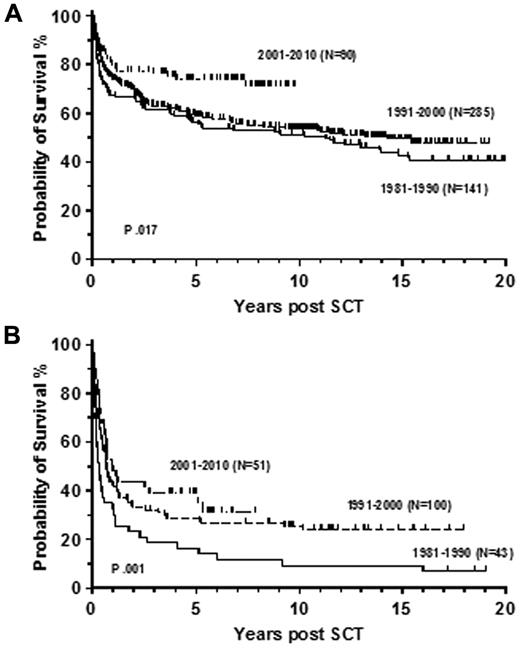

We have observed a similar 3-year survival of 74% in 173 consecutive patients who underwent transplantation in first chronic phase between 2000 and 2010 at Hammersmith Hospital (Figure 5). The 6-year survival of the whole cohort was 72% and patients with EBMT score 0 or 1 had a 3-year probability of survival of 89%. Similar to the registry studies we also demonstrated a significant improvement in survival compared with previous decades (Figure 6A). There was no statistically significant improvement in the survival of patients with advanced phase disease whose 3-year survival was 40% in the recent decade (Figure 6B). Similar results were recently reported in a German multicenter study, describing 84 patients who underwent transplantation after pretreatment with imatinib. Nineteen patients with EBMT score 0 or 1 had early transplantation, 37 underwent transplantation after imatinib failure, and 28 for advanced phase disease. The estimated 3-year survival rate of patients in chronic and advanced phase was 91% and 59%, respectively.108

Recent survival of patients allografted for CML. Survival of 173 patients allografted for CML at Hammersmith Hospital, London, from January 2000 to December 2010 stratified by EBMT risk score.

Recent survival of patients allografted for CML. Survival of 173 patients allografted for CML at Hammersmith Hospital, London, from January 2000 to December 2010 stratified by EBMT risk score.

Survival rates by decade of transplantation. Probability of overall survival for patients with CML in first chronic (A) and advanced (B) phase after allogeneic transplantation at the Hammersmith Hospital, London, stratified by decade of transplantation.

Survival rates by decade of transplantation. Probability of overall survival for patients with CML in first chronic (A) and advanced (B) phase after allogeneic transplantation at the Hammersmith Hospital, London, stratified by decade of transplantation.

A large retrospective registry study of 2444 patients who received myeloablative allo-SCT for CML in first chronic phase between 1978 and 1998 addressed the issue of durability of response and the incidence of late relapse. All included patients had survived in continuous complete remission for at least 5 years (median follow-up, 11 years; range, 5-25 years). The study confirmed good long-term results of allografting in CML, with an overall survival rate at 15 years of 88% for patients with sibling donors and 87% for those who received unrelated cells. The corresponding cumulative incidences of relapse were only 8% and 2%, respectively, with the last relapse reported 18 years after transplantation. In multivariate analyses, a history of chronic GVHD increased the risks for late overall mortality and NRM but reduced the risk for relapse. In comparison with normal age-matched populations, the mortality of recipients of allo-SCT was significantly higher until 14 years after allo-SCT, but thereafter it became similar to that of a general population.109

Conclusion

The last decade has witnessed a dramatic change in practice with a decline in the primary use of allo-SCT for CML after the introduction of TKI. However, a significant proportion of patients fail to respond and/or develop intolerance to TKI.

Transplantation remains the only potentially curative option for patients in accelerated or blast phase, patients with T315I mutation and after failure or intolerance of second-generation TKI (Table 2). The decision for transplantation involves careful balancing of the risks for allo-SCT against the risk for disease progression in each individual patient.

Summary of indications for allo-SCT in CML

| Phase . | Indications . |

|---|---|

| Blast | As soon as possible after re-establishing chronic phase with TKI or chemotherapy (consider use postengraftment therapy with second generation TKI) |

| Accelerated | Less advanced accelerated phase at diagnosis: treat as first chronic phase Near blast phase or evolution into accelerated phase on TKI: treat as blast phase |

| First chronic | Failure of second-generation TKI (donor search should be undertaken after failure of imatinib) imatinib failure and T315I BCR-ABL1 mutation |

| Phase . | Indications . |

|---|---|

| Blast | As soon as possible after re-establishing chronic phase with TKI or chemotherapy (consider use postengraftment therapy with second generation TKI) |

| Accelerated | Less advanced accelerated phase at diagnosis: treat as first chronic phase Near blast phase or evolution into accelerated phase on TKI: treat as blast phase |

| First chronic | Failure of second-generation TKI (donor search should be undertaken after failure of imatinib) imatinib failure and T315I BCR-ABL1 mutation |

Transplantation for CML has not only benefited individual patients who have been cured as a consequence but has been hugely instructive in the fields of transplantation and immunotherapy (Table 3). Information gained from this disease has benefited many other hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. CML has been rightly described as a paradigm for malignancy and remains so as we work toward solving the remaining questions, not least of which are questions on the mechanisms of disease progression and the nature of the leukemic stem cell. CML has further lessons for the cancer community, and these are likely to have a far-ranging influence.

Ten lessons from transplantation in CML

| No. . | Lesson . |

|---|---|

| 1 | Stem cells can circulate in the peripheral blood. |

| 2 | Peripheral blood and bone marrow stem cells will engraft after myeloablative therapy. |

| 3 | Autografting with Ph-positive cells can result in regeneration with Ph-negative cells. |

| 4 | Allografting can cure CML. |

| 5 | T-cell depletion is associated with an increased risk of relapse. |

| 6 | Infusion of lymphocytes can restore remission. |

| 7 | Elucidation of mechanisms of GVL effect |

| 8 | Development and clinical value of monitoring for minimal residual disease |

| 9 | EBMT (Gratwohl) score can be applied to all diseases. |

| 10 | Relapse can occur very late after transplantation and life-long vigilance is required. |

| No. . | Lesson . |

|---|---|

| 1 | Stem cells can circulate in the peripheral blood. |

| 2 | Peripheral blood and bone marrow stem cells will engraft after myeloablative therapy. |

| 3 | Autografting with Ph-positive cells can result in regeneration with Ph-negative cells. |

| 4 | Allografting can cure CML. |

| 5 | T-cell depletion is associated with an increased risk of relapse. |

| 6 | Infusion of lymphocytes can restore remission. |

| 7 | Elucidation of mechanisms of GVL effect |

| 8 | Development and clinical value of monitoring for minimal residual disease |

| 9 | EBMT (Gratwohl) score can be applied to all diseases. |

| 10 | Relapse can occur very late after transplantation and life-long vigilance is required. |

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

Authorship

Contribution: J.P., J.M.G., and J.F.A. wrote the manuscript; and R.M.S. analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jiří Pavlů, Department of Haematology, Hammersmith Hospital, Rm 2.20 Catherine Lewis Centre, 2nd Floor Leuka Bldg, Du Cane Rd, London, W12 0HS United Kingdom; e-mail: jiri.pavlu@imperial.nhs.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal