Abstract

Mast cell (MC) differentiation, survival, and activation are controlled by the membrane tyrosine kinase c-Kit upon interaction with stem cell factor (SCF). Here we describe a single point mutation induced by N-ethyl-N-nitrosurea (ENU) mutagenesis in C57BL/6J mice—an A to T transversion at position 2388 (exon 17) of the c-Kit gene, resulting in the isoleucine 787 substitution by phenylalanine (787F), and analyze the consequences of this mutation for ligand binding, signaling, and MC development. The Kit787F/787F mice carrying the single amino acid exchange of c-Kit lacks both mucosal and connective tissue-type MCs. In bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs), the 787F mutation does not affect SCF binding and c-Kit receptor shedding, but strongly impairs SCF-induced cytokine production, degranulation enhancement, and apoptosis rescue. Interestingly, c-Kit downstream signaling in 787F BMMCs is normally initiated (Erk1/2 and p38 activation as well as c-Kit autophosphorylation) but fails to be sustained thereafter. In addition, 787F c-Kit does not efficiently mediate Cbl activation, leading to the absence of subsequent receptor ubiquitination and impaired c-Kit internalization. Thus, I787 provides nonredundant signals for c-Kit internalization and functionality.

Introduction

Mast cells (MCs) are potent effector cells that play a key role in allergic disorders, autoimmunity, inflammation, and protective immune responses against bacteria and parasites.1-5 MCs differentiate from multipotent hematopoietic progenitors in the bone marrow and migrate to connective and mucosal tissues where maturation mainly occurs.6,7 MC numbers are increased at the site of inflammation and regulated via proliferative and antiapoptotic mechanisms. Signaling through the membrane receptor tyrosine kinase c-Kit is essential for both human and mouse MC development, survival, maturation, and activation.7 Furthermore, stem cell factor (SCF), the specific c-Kit ligand, acts as the major chemotactic factor for MCs.8

The c-Kit receptor is a 975-amino acid protein composed of an extracellular ligand-binding domain which contains 5 immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains and a single transmembrane domain. The cytoplasmic region of c-kit contains a split protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) domain with an insert of 77 hydrophilic amino acids. The crystal structure of c-Kit revealed that SCF interacts with the first, second, and third Ig-like domains.9,10 Upon ligand binding, the fourth and fifth Ig domains of 2 neighboring c-Kit ectodomains are brought closer, stabilizing the interaction between 2 receptor molecules.10 The cytoplasmic region carrying the protein tyrosine kinase domain displays a bilobed architecture with a small N-terminal lobe (amino acids 582-671), and a large C-terminal lobe (amino acids 678-953).11-13 The cleft generated between the 2 lobes contains the kinase catalytic site. Bivalent binding of SCF to c-Kit leads to receptor dimerization, autophosphorylation, creates binding sites for SH2-containing phosphotyrosine-binding proteins, and induces kinase activation. A large number of signaling molecules has been identified as either interacting or as substrate proteins for c-Kit. These include the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase (PI3K), phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), Src family tyrosine kinases, and the adaptor proteins Grb2, Grb7, and APS.14-16 PI3K-mediated activation of protein kinase B (PKB, Akt), the Ras-mitogen–activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, the Jak-Stat pathway, and Ca2+ signaling are examples of c-Kit downstream signaling cascades affecting multiple cellular functions.

c-Kit mutations have been identified in the membrane proximal Ig-like domain (exon 8 and 9), in the juxtamembrane domain (exon 11), and in the tyrosine kinase domain. Naturally occurring mouse mutants for c-Kit and mouse strains generated by site-directed mutagenesis indicate that most of the mutations that affect MC development are loss-of-function mutations. In humans, loss-of-function mutations in c-Kit result in piebaldism,17 an autosomal dominant disease characterized by a white forelock and large, nonpigmented patches on the forehead, eyebrows, chin, chest, abdomen, and extremities corresponding with a loss of MCs in affected skin areas.18 However, several point mutations in the tyrosine kinase, juxtamembrane, or transmembrane domain lead to ligand-independent constitutive activation of c-Kit and systemic mastocytosis.19,20

Here we describe a novel point mutation, an A to T transversion at position 2388 of the c-Kit gene (at the Pretty2 allele also known as m2Btlr), which results in the substitution of isoleucine 787 (I787) by phenylalanine, and analyze the consequences of this amino acid substitution for c-Kit signaling and MC development.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6J mice were used for N-ethyl-N-nitrosurea (ENU) mutagenesis to generate the Kit787F/787F (Kit787F) strain. Four- to 6-week-old mice were analyzed. The Kit787F mutation was observed in G1 mice born to ENU mutagenized sires (pure C57BL/6J background) and mapped as a dominant phenotype by outcrossing an affected animal to C3H/HeN and outcrossing a second time to the same strain. On 34 meioses, the mutation was confined to a critical region bounded by D5Mit352 and D5Mit158. This interval contained the Kit gene, which was sequenced. The stock was maintained by crossing for 6 generations to C57BL/6J. Genetically MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/KitW-v (KitW/KitW-v) and control WBB6F1-Kit+/+ (Kit+/+) mice were bred in the Animal Care Facility of the Research Center Borstel and housed in specific pathogen–free facility. All experiments were performed according to institutional guidelines. Eight-week-old KitW/KitW-v mice were reconstituted with 3 × 106 wild-type or Kit787F bone marrow–derived mast cells (BMMCs) injected intraperitoneally. Six weeks after reconstitution peritoneal cells (PECs) were analyzed for the presence of MCs by fluorescence-activated cell scanning (FACS).

Cell isolation, generation, culture, and stimulation

PECs were isolated by peritoneal lavage with 10 mL of cold 0.9% NaCl solution. BMMCs were generated by cultivation of bone marrow cells from Kit787F, Kit787F/+, and control C57BL/6 mice in the presence of recombinant murine interleukin-3 (IL-3). Cells were maintained in complete medium consisting of 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Biochrom), 50μM β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), nonessential amino acids, 2mM l-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, and 1mM sodium pyruvat (all from Invitrogen) in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; PAA) supplemented with 5 ng/mL IL-3 (R&D Systems). After 4 weeks of culture, BMMCs represented > 98% of the total cells according to FACS analysis of cell-surface expression of T1/ST2 and FcεRI and were negative for CD11c, B220, F4/80, Gr-1, and CD3 expression. BA/F3 cells (pro-B-cell line) were cultivated in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS and 10 ng/mL IL-3.

To analyze cytokine production, BMMCs (2 × 106/mL) were stimulated with SCF (R&D Systems), IgE (SPE-1; Sigma), dinitrophenylated human serum albumin (DNP-HSA; Sigma), lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Salmonella enterica serovar Friedenau, kindly provided by H. Brade, Research Center Borstel, and purified as previously described21 ) or phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) and Ionomycin (both from Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Supernatants were collected, and cytokines and chemokines were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) using specific antibodies and standard proteins from R&D Systems. To analyze BMMC proliferation in response to IL-3, 2 × 106 cells/mL were incubated with IL-3 for 72 hours, and 1 μCi 3H-thymidine was added for the last 18 hours. Measurement of histamine by o-phthaldialdehyde assay,22 measurement of MC degranulation by β-hexosaminidase release,23 RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and conventional semiquantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for MC proteases are described in the supplemental data (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Cloning of c-Kit and transfection of BA/F3 cells

Sequencing of cDNA and genomic DNA, and in silico protein analysis are described in the supplemental data. To clone mouse c-Kit (CD117, c-Kit, accession number of NM_001122733) into the entry vector pDONR221, the coding sequence was first amplified from a mouse cDNA library using the forward primer 5′-CACCATGAGAGGCGCTCGCGGCGCCTGGG-3′ and the reverse primer including a c-Kit-stop codon 5′-TCAGGCATCTTCGT GCACGAGCAGGGG-3′. After sequencing of the 2944-bp insert, a c-Kit-pDON221 clone was recombined with Invitrogen pDEST-40 expression vector according to the manufacturer's instructions. c-Kit cDNA-mutant (2388A→T) was generated by PCR amplification of 2 c-Kit fragments overlapping at the mutation site. Briefly, c-Kit upstream fragment of 2395 bp was amplified from cDNA library using the forward primer 5′-CACCATGAGAGGCGCTCGCGGCGCCTGGG-3′ and the reverse primer carrying the mutation 5′-GGCTGCCAAATCTCTGTGAAAACAATTCTTGGAGGCGAGGA-3′. The c-Kit downstream fragment of 590 bp was amplified from cDNA library using the forward primer carrying the mutation 5′-TCCTCGCCTCCAAGAATTGTTTTCACAGAGATTTGGC AGCC-3′ and the reverse primer with the c-Kit stop codon 5′-TCAGGCATCTTCGTGCACGAGCAGGGG-3′. Both fragments were purified and mixed in a final PCR to generate the c-Kit coding sequence of 2944 bp carrying the A→T mutation resulting in an exchange of amino acid I787 to phenylalanine. The cloning procedure of the c-Kit mutant into the expression vector pDEST40 was as described above for the c-Kit wild-type cDNA.

To transiently transfect BA/F3 cells, the Cell Line Nucleofector kit V (Lonza) was used. For transfection, 2 × 106 cells were washed and resuspended in 100 μL of Nucleofector solution V together with the 6 μg DNA. Cells were pulsed in the Nucleofector I Device (Lonza) and subsequently transferred into a 6-well plate containing 2 mL of culturing medium. Twenty-four hours after the transfection, the transient c-Kit expression was measured by flow cytometry.

To obtain stable clones, the cells were selected for 2 weeks with 600 μg/mL G-418 (PAA). For this purpose, 24 hours after transfection, cells were diluted out into 96-well plates from a starting density of 3 × 103 cells/mL.

FACS analysis

Cells were washed twice in FACS buffer (2% newborn calf serum, 0.1% NaN3, 2mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA] in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and staining with phycoerythrin (PE)–, allophycocyanin (APC)–, or fluorescein isothyocyanate (FITC)–conjugated antibodies against cell-surface molecules. Monoclonal antibodies against CD117 (c-Kit, 2B8), CD16/32 (Fcγ III/II, 2.4G2), CD54 (3E2), CD81 (Eat2; all from BD PharMingen), T1/ST2 (DJ8; Morwell Diagnostics), CD53 (OX-80), Serotec, FcεRI (MAR-1; eBioscience) were used for surface staining. To prevent nonspecific binding, all samples were preincubated with Fc-Block or unlabeled isotype matched nonspecific antibodies (BD PharMingen). Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) according to standard protocols. Gates on viable cells were set according to exclusion of propidium iodide (PI) staining. To assess SCF binding, cells were washed with PBS/5% FCS and preincubated on ice for 2 hours. Recombinant mouse SCF (R&D Systems) was added, cells were washed twice and then incubated with biotinylated goat α-SCF (R&D Systems) following the incubation with streptavidin (SA)-PE (Dianova). All incubation steps were performed on ice, all washing steps at 250g at 4°C. To measure ligand-receptor internalization, cells were preincubated for 2 hours on ice, then 50 ng/mL SCF were added, cells were incubated on ice for 1 hour, and then washed twice. Internalization was induced by incubation of cells at 37°C, stopped by the addition of ice-cold PBS/5%FCS, and SCF was measured on the cell surface as described above. Inhibition of internalization was performed by preincubation of cells with 100μM Dynasore [3-hydroxynaphthalene-2-carboxylic acid (3,4-dihidroxybenzylidene) hydrazide; Tocris Bioscience] at 37°C for 30 minutes. Receptor internalization was induced and measured as described above. Dynasore was added in all incubation steps.

Apoptosis of BMMCs and stably transfected BA/F3 cells were measured by annexin V FITC kit (Bender MedSystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Histology

Tissue samples were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, Carnoy fixative or Bouin fixative for 24 hours, and then processed for paraffin embedding. Cytospins were prepared by centrifugation of the PECs on glass slides by cytocentrifuge (Shendon). Tissue sections or cytospins were stained with toluidine blue or naphtolesterase (Sigma-Aldrich). Staining for MC protease-2 (MCP-2) was performed by MCP-2–specific antibodies24 and donkey rabbit-specific secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as a substrate.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Cell pellets were lysed for 15 minutes on ice in cell extraction buffer: 1% NP-40, 50mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, 150mM NaCl, 10mM sodium fluoride, 1mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitors (complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche] or 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 10mM phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride [PMSF]). The detergent-insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 13 000 rpm (16 000g) at 4°C. For immunoprecipitation studies, cell lysates were incubated with 0.5-2 μg primary antibody at 4°C overnight followed by addition of 20 μL of Protein A/G beads (Calbiochem) and further incubation for 1 to 2 hours. Immune complexes were collected and washed 4 times with cell extraction buffer. Proteins from cell lysates and from immunoprecipitates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies. Equal cell equivalents were subjected to SDS-PAGE. For some experiments, protein concentrations were determined using a bovine serum albumin (BSA) protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and 50 μg proteins were analyzed by electrophoresis in SDS-PAGE. Antibodies against phospho-Erk1/2, phospho-p38, p38, phospho-PLCγ1, PLCγ1, phospho-c-Kit (Tyr719), c-Kit, PKB (Akt), phospho-p90Rsk, phospho-Stat5 (Tyr694), and phospho-IKKβ were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against Erk1/2, phospho-Cbl (Tyr700), ubiquitin (P4D1), and actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were detected with p-Tyr-100 mouse monoclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology).

Calcium release assay

IgE-preloaded BMMCs (0.15 μg/mL IgE, overnight) were washed with RPMI, resuspended at 5 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI containing 1% FCS, 30μM Indo-1 AM (Invitrogen), and 0.045% pluronic F-127 (Invitrogen) and incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then pelleted, resuspended in RPMI containing 1% FCS, and analyzed in an LSR II (Becton Dickinson) after the indicated stimulation procedures. The FACS profiles were converted to line graph data using the FlowJo application Version 8.8.6 (TreeStar).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the results was performed by Student t test for unpaired samples. A P value lower than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Kit787F mice carry a point mutation in the c-Kit coding region

Kit787F mice generated by ENU mutagenesis of C57BL/6J mice were identified by their distinct coat color pattern. Heterozygotes (Kit787F/+) have a diluted coat color, light ears, and tail, and white spots on the belly and back. Homozygous Kit787F mice have black eyes and a white coat color, indicating a lack of functional melanocytes, which strongly resembles mice carrying a mutation at the white spotting (W) locus, the c-Kit locus on the mouse chromosome 5 (supplemental Figure 1A). In addition, Kit787F mutant mice are infertile, anemic, and show substantial hematopoietic abnormalities (Z.O., M.S., S.B.-P., manuscript in preparation). Therefore, the c-Kit gene was sequenced, and a mutation was identified. Five fragments covering the annotated full-length transcript (accession number NM021099) were amplified from cDNA and directly sequenced by dye terminator sequencing. Genomic DNA was subsequently used to sequence the 21 exons of the gene, including the splice sites. Only 1 mutation was found in mice carrying 1 or 2 mutant alleles corresponding to an A to T transversion at position 2388 of the Kit transcript (Figure 1A). The 787F mutation results in the substitution of I787 by phenylalanine in the C-lobe of the kinase domain (Figure 1A and supplemental Figure 1B), which leads to a change from an aliphatic to an aromatic amino acid in the vicinity of the proton acceptor aspartate at position 790. The protein residue I787 is highly conserved across many vertebrate species (supplemental Figure 1C) from puffer fish to humans, suggesting an essential role of I787 for c-Kit activation and/or signaling.

Kit787F mice carrying a point mutation in c-Kit are MC-deficient. (A) Identification of the Kit787F mutation. A single nucleotide transversion (A to T) results in 787F of the polypeptide chain. The sequence electropherograms of wild-type (wt), heterozygous animals (Kit787F/+), and homozygous mutants (Kit787F) genomic DNAs are shown in the upper panel. Cytospins (B) or sections of ear tissue (C) and trachea (D) from wild-type, heterozygotes (Kit787F/+), or Kit787F mice were subjected to toluidine blue staining (B-C) or naphtolesterase staining (D) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Photos were taken with a light microscope under 200× (C) or 400× (B,D) magnification. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of peritoneal MCs (c-Kithigh, T1/ST2high). Percentages of double-positive cells are indicated. One representative experiment of 6 is shown.

Kit787F mice carrying a point mutation in c-Kit are MC-deficient. (A) Identification of the Kit787F mutation. A single nucleotide transversion (A to T) results in 787F of the polypeptide chain. The sequence electropherograms of wild-type (wt), heterozygous animals (Kit787F/+), and homozygous mutants (Kit787F) genomic DNAs are shown in the upper panel. Cytospins (B) or sections of ear tissue (C) and trachea (D) from wild-type, heterozygotes (Kit787F/+), or Kit787F mice were subjected to toluidine blue staining (B-C) or naphtolesterase staining (D) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Photos were taken with a light microscope under 200× (C) or 400× (B,D) magnification. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of peritoneal MCs (c-Kithigh, T1/ST2high). Percentages of double-positive cells are indicated. One representative experiment of 6 is shown.

The 787F mutation leads to complete MC deficiency in vivo

Since mutations in c-Kit are known to affect MC development, we tested whether the 787F mutation has an effect on MC differentiation in vivo. As shown in Figure 1, MCs were absent in Kit787F and markedly reduced in Kit787F/+ in peritoneum (2.8% ± 0.7% of peritoneal cells; n = 7 in wild-type vs 1.5% ± 0.4%; n = 6 in Kit787F/+), as demonstrated by toluidine blue staining and FACS analysis (Figure 1B,E), ear tissue, peripheral lymph nodes, and skin stained by toluidine blue (Figure 1C and supplemental Figure 2A-B), trachea and stomach stained for chloroacetate esterase activity (Figure 1D and supplemental Figure 2C), and spleen, trachea, and lymph nodes stained for mouse MCP-2 (mMCP-2; supplemental Figure 2D and data not shown). These data demonstrate that the 787F mutation leads to the loss-of-function of c-Kit and a complete developmental block of both mucosal and connective tissue-type MCs in vivo.

IL-3–driven MC differentiation in vitro is not affected by the Kit787F mutation

To investigate the effect of the 787F mutation on MC differentiation in vitro, bone marrow cells of wild-type and Kit787F mice were cultured in the presence of IL-3. BMMCs were generated, and expression of characteristic surface receptors, histamine content, protease expression, and proliferation as well as signaling in response to IL-3 were analyzed. Wild-type and Kit787F BMMCs display a comparable expression of the high affinity IgE receptor, FcεRI, the IL-33 receptor ST2, CD16/32 (Fcγ III/II receptor), tetraspanins CD53 and CD81, and adhesion molecule CD54/ICAM-1 (supplemental Figure 3A). Furthermore, histamine content and expression of MC proteases (supplemental Figure 3B-C), as well as IL-3–induced proliferation and signaling (supplemental Figure 4A-B; Stat5, Erk1/2, and PKB phosphorylation) were also comparable between Kit787F and wild-type BMMCs. These data suggest that IL-3–driven BMMCs differentiation in vitro is not affected by the c-Kit 787F mutation.

I787 substitution does not affect SCF binding or c-Kit shedding

To study whether the 787F mutation modulates c-Kit expression, wild-type and Kit787F BMMCs were analyzed by FACS using c-Kit–specific monoclonal antibodies. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) after staining with c-Kit–specific antibodies was slightly reduced in Kit787F BMMCs compared with wild-type BMMCs (244 ± 41; n = 7 in wild-type BMMCs vs 158 ± 10; n = 9 in Kit787F BMMCs; P = .038; Figure 2A). However, Kit787F BMMCs do not display any significant difference in the ligand binding ability, measured as MFI of BMMCs preincubated with SCF and stained with α-SCF antibodies (Figure 2B). Because SCF is a dimer and binds with high avidity to the receptor dimer, one can conclude that both mutant and wild-type c-Kit receptors dimerize at a comparable level of efficiency.

787F mutation does not affect c-Kit expression, SCF binding, and c-Kit shedding. (A) BMMCs (0.5 × 106) from wild-type and Kit787F mice were stained with PE-labeled c-Kit–specific antibodies, and MFI was measured by FACS (n = 7-9; *P = .038). Means are indicated as lines. (B) To compare SCF binding, cells were preincubated on ice for 2 hours, washed, and recombinant mouse SCF was added. One representative experiment from 3 is shown. BMMCs from 3 independent wild-type and Kit787F BMMC cultures were analyzed. (C) c-Kit shedding was comparable in wild-type and Kit787F BMMCs and was induced by incubation with PMA (100 ng/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were stained with APC-labeled c-Kit–specific antibodies and analyzed by FACS. Gray histograms show c-Kit expression in untreated controls, white histograms show c-Kit expression after PMA-induced shedding, dashed-line histograms show isotype control. One representative experiment from 3 is shown.

787F mutation does not affect c-Kit expression, SCF binding, and c-Kit shedding. (A) BMMCs (0.5 × 106) from wild-type and Kit787F mice were stained with PE-labeled c-Kit–specific antibodies, and MFI was measured by FACS (n = 7-9; *P = .038). Means are indicated as lines. (B) To compare SCF binding, cells were preincubated on ice for 2 hours, washed, and recombinant mouse SCF was added. One representative experiment from 3 is shown. BMMCs from 3 independent wild-type and Kit787F BMMC cultures were analyzed. (C) c-Kit shedding was comparable in wild-type and Kit787F BMMCs and was induced by incubation with PMA (100 ng/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were stained with APC-labeled c-Kit–specific antibodies and analyzed by FACS. Gray histograms show c-Kit expression in untreated controls, white histograms show c-Kit expression after PMA-induced shedding, dashed-line histograms show isotype control. One representative experiment from 3 is shown.

A mechanism that is well known to control receptor signaling is shedding. Because tumor necrosis factor α-converting enzyme (TACE)-mediated cleavage of c-Kit generates a soluble receptor form that blocks SCF activities in vitro and in vivo,25-27 we investigated whether c-Kit shedding in 787F BMMCs is affected. Interestingly, c-Kit receptor shedding induced by PMA was comparable between wild-type and Kit787F BMMCs (Figure 2C). Thus, despite the slightly reduced c-Kit expression in Kit787F BMMCs, the 787F mutation does not affect ligand binding and receptor shedding.

BMMCs carrying the 787F mutation are defective in SCF-mediated activities

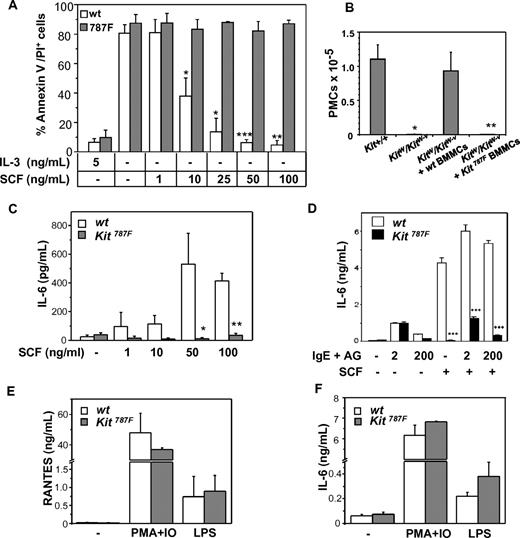

To investigate the functional consequences of the 787F c-Kit mutation, the ability of SCF to prevent MC apoptosis induced by growth factor deprivation was tested. As shown in Figure 3A, IL-3 withdrawal induced a strong and comparable apoptosis in Kit787F and wild-type BMMCs. However, the addition of SCF in the culture medium rescued wild-type, but not Kit787F BMMCs from cell death in a dose-dependent manner.

Effect of 787F mutation on MC function. (A) SCF treatment does not rescue BMMCs carrying the 787F mutation from apoptosis induced by IL-3 deprivation. BMMCs were cultured with indicating concentrations of SCF for 48 hours, and apoptosis was measured using annexinV/PI staining. BMMCs without cytokines or treated with 5 ng/mL IL-3 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. BMMC cultures generated from individual animals were analyzed. One representative experiment of 4 is shown (*P = .02; **P = .002; ***P = 4 × 10−4; n = 3). (B) Kit787F BMMCs do not reconstitute MC-deficient KitW/Kit W-v mice in vivo. KitW/KitW-v mice were reconstituted with 3 × 106 wild-type (wt) or Kit787F (787F) BMMCs intraperitoneally, PECs were analyzed by FACS, and the number of c-Kithigh, T1/ST2high peritoneal MCs were assessed 6 weeks later (*P = .006; **P = 3 × 10−4; n = 3-5). (C) MCs from Kit787F mice do not produce IL-6 upon SCF stimulation. BMMCs from wild-type and Kit787F mice were left untreated or treated with increasing concentration of SCF for 48 hours, and IL-6 was measured in supernatants by ELISA. Mean values from 4 independent experiments ± SEM are shown (*P = .04; **P = 7 × 10−6; n = 4-8). (D) Stimulation with SCF (100 ng/mL) does not further increase IL-6 production induced by IgE and antigen in Kit787F BMMCs. Cells were stimulated for 3 hours, and IL-6 was measured in supernatants by ELISA (***P < 5 × 10−4). Mean values from 3 independent experiments ± SD are shown. RANTES (E) or IL-6 (F) production induced by PMA and ionomycin or LPS is comparable in wild-type and Kit787F BMMCs. Cells were stimulated for 48 hours, and concentration of IL-6 or RANTES was measured in the supernatants. Mean values from 3 independent experiments ± SEM are shown.

Effect of 787F mutation on MC function. (A) SCF treatment does not rescue BMMCs carrying the 787F mutation from apoptosis induced by IL-3 deprivation. BMMCs were cultured with indicating concentrations of SCF for 48 hours, and apoptosis was measured using annexinV/PI staining. BMMCs without cytokines or treated with 5 ng/mL IL-3 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. BMMC cultures generated from individual animals were analyzed. One representative experiment of 4 is shown (*P = .02; **P = .002; ***P = 4 × 10−4; n = 3). (B) Kit787F BMMCs do not reconstitute MC-deficient KitW/Kit W-v mice in vivo. KitW/KitW-v mice were reconstituted with 3 × 106 wild-type (wt) or Kit787F (787F) BMMCs intraperitoneally, PECs were analyzed by FACS, and the number of c-Kithigh, T1/ST2high peritoneal MCs were assessed 6 weeks later (*P = .006; **P = 3 × 10−4; n = 3-5). (C) MCs from Kit787F mice do not produce IL-6 upon SCF stimulation. BMMCs from wild-type and Kit787F mice were left untreated or treated with increasing concentration of SCF for 48 hours, and IL-6 was measured in supernatants by ELISA. Mean values from 4 independent experiments ± SEM are shown (*P = .04; **P = 7 × 10−6; n = 4-8). (D) Stimulation with SCF (100 ng/mL) does not further increase IL-6 production induced by IgE and antigen in Kit787F BMMCs. Cells were stimulated for 3 hours, and IL-6 was measured in supernatants by ELISA (***P < 5 × 10−4). Mean values from 3 independent experiments ± SD are shown. RANTES (E) or IL-6 (F) production induced by PMA and ionomycin or LPS is comparable in wild-type and Kit787F BMMCs. Cells were stimulated for 48 hours, and concentration of IL-6 or RANTES was measured in the supernatants. Mean values from 3 independent experiments ± SEM are shown.

Next, the ability of in vitro differentiated Kit787F BMMCs to reconstitute MC-deficient mice and to survive in vivo was tested. Kit787F BMMCs and wild-type BMMCs used as controls were injected intraperitoneally into MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/KitW-v (KitW/KitW-v) mice, and peritoneal MC numbers were determined by FACS 4 weeks later (Figure 3B). Contrary to wild-type BMMCs, Kit787F BMMCs did not reconstitute the peritoneal MC population in MC-deficient mice, indicating that c-Kit–mediated survival signals are essential and nonredundant for long-lasting MC survival in vivo.

Next, the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, was tested in Kit787F and Kit787F/+ BMMCs and compared with wild-type BMMCs upon SCF stimulation. SCF neither induced IL-6 release in Kit787F BMMCs (Figure 3C) nor enhanced the FcεRI-mediated cytokine production (Figure 3D), whereas Kit787F/+ BMMCs showed a 75% decrease in IL-6 production (supplemental Figure 5A). In contrast, cytokine production induced by LPS or PMA and ionomycin was comparable between Kit787F and wild-type BMMCs (Figure 3E-F). Furthermore, degranulation of BMMCs in response to IgE and antigen (AG) was comparable between wild-type, Kit787F/+ and Kit787F BMMCs (supplemental Figure 5B), but an SCF-mediated degranulation enhancement could be detected only in wild-type BMMCs (data not shown). Thus, the 787F mutation in BMMCs specifically affects SCF-mediated cytokine production and SCF-driven rescue from apoptosis.

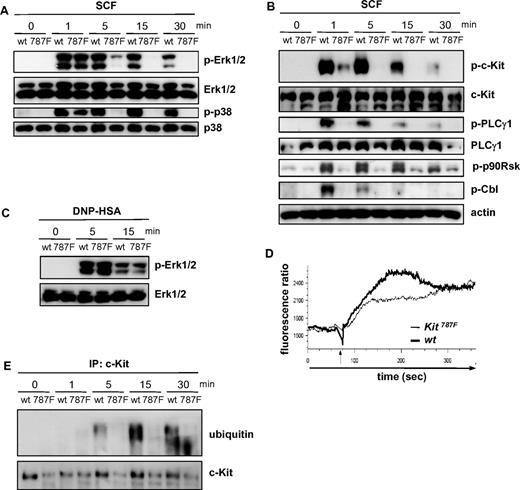

I787 substitution leads to an impaired SCF-mediated signal transduction

To assess the effects of the 787F mutation on c-Kit–mediated signal transduction, we stimulated BMMCs with SCF and monitored the activation of various signaling parameters. SCF stimulation rapidly induces the phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and p38 in BMMCs. While at early times (1 minute) after SCF treatment the activation of these MAPKs was comparable in wild-type, Kit787F/+, and Kit787F BMMCs, SCF-induced Erk1/2 and p38 activation was decreased in Kit787F/+ BMMCs and impaired at later time points in Kit787F BMMCs (Figure 4A and supplemental Figure 5C). In wild-type cells, phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and p38 was maintained for at least 15 to 30 minutes, whereas MAPK activation was hardly detectable in Kit787F BMMCs after 5 minutes of SCF stimulation (Figure 4A). Interestingly, phosphorylation of p90Rsk, a downstream target of Erk1/2, was strongly induced in wild-type MCs, but largely abolished in Kit787F MCs (Figure 4B), indicating that the short and transient activation of Erk1/2 in Kit787F BMMCs was not sufficient for efficient downstream signal propagation.

The 787F mutation impairs c-Kit downstream signaling. (A) BMMCs from wild-type (wt) and Kit787F (787F) mice were stimulated for the indicated times with SCF (100 ng/mL). Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for (phospho-)Erk1/2 and p38 (A) or (phospho-)c-Kit, PLCγ1, p90Rsk, Cbl, and actin (B). (C) IgE-preloaded BMMCs from wild-type (wt) and Kit787F (787F) mice were stimulated for the indicated times with antigen (DNP-HSA; 50 ng/mL). Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for (phospho-)Erk1/2. (D) BMMCs from wild-type and Kit787F mice were stimulated with SCF (100 ng/mL), and calcium mobilization was measured. The arrow marks the SCF addition. BMMCs generated from 3-5 mice of each genotype were analyzed. Comparable results were obtained with BMMCs from different cultures. Representative curves are shown. At least 3 independent experiments were performed. (E) BMMCs from wild-type (wt) and Kit787F (787F) mice were stimulated for the indicated times with SCF (100 ng/mL). Cellular lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an antibody against c-Kit, and immunoprecipitated c-Kit was analyzed by immunoblotting for ubiquitin. Immunoblotting with c-Kit–specific antibodies served as a loading control.

The 787F mutation impairs c-Kit downstream signaling. (A) BMMCs from wild-type (wt) and Kit787F (787F) mice were stimulated for the indicated times with SCF (100 ng/mL). Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for (phospho-)Erk1/2 and p38 (A) or (phospho-)c-Kit, PLCγ1, p90Rsk, Cbl, and actin (B). (C) IgE-preloaded BMMCs from wild-type (wt) and Kit787F (787F) mice were stimulated for the indicated times with antigen (DNP-HSA; 50 ng/mL). Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for (phospho-)Erk1/2. (D) BMMCs from wild-type and Kit787F mice were stimulated with SCF (100 ng/mL), and calcium mobilization was measured. The arrow marks the SCF addition. BMMCs generated from 3-5 mice of each genotype were analyzed. Comparable results were obtained with BMMCs from different cultures. Representative curves are shown. At least 3 independent experiments were performed. (E) BMMCs from wild-type (wt) and Kit787F (787F) mice were stimulated for the indicated times with SCF (100 ng/mL). Cellular lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an antibody against c-Kit, and immunoprecipitated c-Kit was analyzed by immunoblotting for ubiquitin. Immunoblotting with c-Kit–specific antibodies served as a loading control.

A similar failure of Kit787F BMMCs to sustain SCF-mediated signaling was observed for the SCF-induced activation of PKB (supplemental Figure 6B). Signal transduction was not generally altered in Kit787F BMMCs, as FcεRI-mediated activation of Erk1/2, p38, PKB, IKKβ, and PLCγ1 as well as calcium influx was normal in Kit787F BMMCs (Figure 4C, supplemental Figure 6B,D, and data not shown).

c-Kit-induced activation of PKB is mediated via PI3K and is thought to depend on the recruitment of the regulatory p85 subunit of PI3K to phosphorylated Y719 of c-Kit. Analysis of tyrosine phosphorylation revealed marked impairment of c-Kit Y719 phosphorylation in SCF-stimulated Kit787F BMMCs compared with wild-type BMMCs (Figure 4B). Only at 30 seconds after SCF stimulation was autophosphorylation of 787F mutant c-Kit detectable, although at strongly reduced levels compared with wild-type cells (supplemental Figure 6A). Consistent with significantly attenuated autophosphorylation of 787F c-Kit, only small amounts of p85 were found in c-Kit immunoprecipitates of SCF-stimulated Kit787F BMMCs (supplemental Figure 6C). Calcium mobilization, mediated through PLCγ activation and regulated by PI3K, is quickly induced by SCF.28 PLCγ1 phosphorylation in response to stimulation with SCF was hardly detectable in Kit787F BMMCs, but was rapidly induced in wild-type BMMCs (Figure 4B). Concomitantly to the strongly reduced activation of PLCγ1, SCF-induced calcium signaling was also significantly attenuated in Kit787F BMMCs, although an initial influx of calcium could still be observed (Figure 4D). Recently it has been demonstrated that c-Kit stimulation also induces the phosphorylation and activation of the ubiquitin E3 ligase Cbl, which mediates c-Kit ubiquitination and receptor internalization.29,30 While in wild-type cells, Cbl phosphorylation was observed as early as 1 minute upon SCF-stimulation, Cbl activation was hardly detectable in Kit787F BMMCs (Figure 4B). Moreover, immunoprecipitation experiments clearly demonstrated c-Kit ubiquitination in response to SCF-stimulation in wild-type cells, which was largely defective in Kit787F BMMCs (Figure 4E). Thus, 787F c-Kit does not efficiently mediate Cbl activation and subsequent receptor ubiquitination, suggesting that c-Kit internalization may be defective in Kit787F BMMCs.

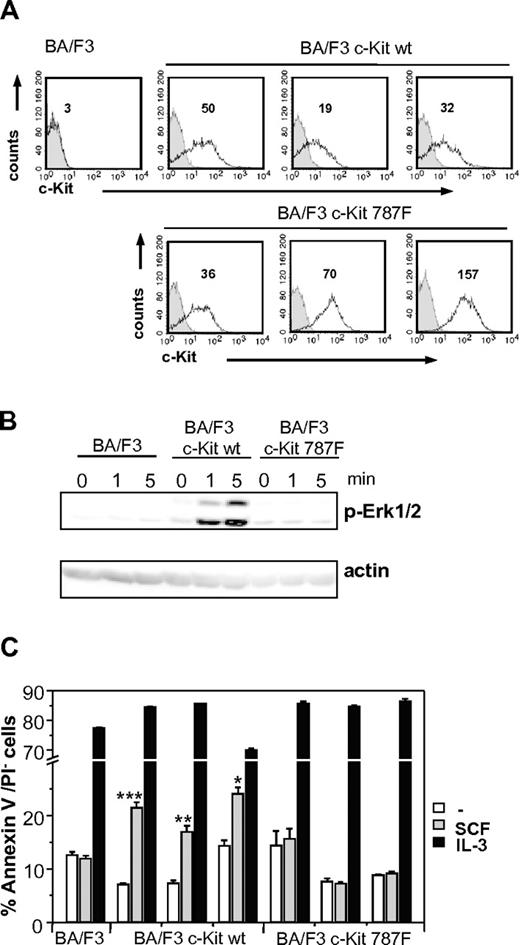

As additional proof of our findings, wild-type and mutant c-Kit cDNA were cloned and stably transfected in BA/F3 cells (BA/F3 c-Kit and BA/F3 c-Kit787F, respectively). BA/F3 c-Kit or BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells were stimulated with SCF at different time points, and SCF-mediated Erk1/2 phosphorylation was investigated. Despite expressing high levels of c-Kit on the cell surface, as measured by anti-c-Kit FACS staining (Figure 5A), the BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells did not show any Erk1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 5B). Furthermore, as shown in Figure 5C, only BA/F3 c-Kit and not BA/F3 c-Kit787F are successfully rescued from cell death in response to SCF, while IL-3 is equally effective in mediating cell survival. This proves that the substitution of I787 by phenylalanine in c-Kit is responsible for the defect in SCF-mediated c-Kit signaling.

SCF-mediated c-Kit signaling in stably transfected BA/F3 cell lines. (A) c-Kit expression in stable transfected BA/F3 cell lines was measured by surface staining of stably transfected BA/F3 c-Kit and BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells. Staining with c-Kit–specific antibodies of 3 different BA/F3 c-Kit and BA/F3 c-Kit787F cell lines each (white histograms, MFI indicated) and isotype controls (gray histograms) are shown. One representative experiment from 3 is shown. (B) Untransfected BA/F3 cells or stably transfected BA/F3 c-Kit and BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells were left unstimulated or stimulated with 100 ng/mL SCF for 1 and 5 minutes. Postnuclear supernatants were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for (phospho-)Erk1/2 and actin (loading control). One representative experiment from 3 is shown. (C) SCF increases survival of stably transfected BA/F3 c-Kit, but not BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells in the absence of IL-3. Stably transfected BA/F3 c-Kit cells (3 different cell lines), BA/F3 c-Kit787F (3 different cell lines), and untransfected controls were left untreated or stimulated with SCF (100 ng/mL) or IL-3 (5 ng/mL) for 48 hours. Cell survival was measured using annexinV/PI staining. One representative experiment from 4 is shown (*P = 9 × 10−4;**P = 2 × 10−4; ***P = 8 × 10−6).

SCF-mediated c-Kit signaling in stably transfected BA/F3 cell lines. (A) c-Kit expression in stable transfected BA/F3 cell lines was measured by surface staining of stably transfected BA/F3 c-Kit and BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells. Staining with c-Kit–specific antibodies of 3 different BA/F3 c-Kit and BA/F3 c-Kit787F cell lines each (white histograms, MFI indicated) and isotype controls (gray histograms) are shown. One representative experiment from 3 is shown. (B) Untransfected BA/F3 cells or stably transfected BA/F3 c-Kit and BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells were left unstimulated or stimulated with 100 ng/mL SCF for 1 and 5 minutes. Postnuclear supernatants were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for (phospho-)Erk1/2 and actin (loading control). One representative experiment from 3 is shown. (C) SCF increases survival of stably transfected BA/F3 c-Kit, but not BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells in the absence of IL-3. Stably transfected BA/F3 c-Kit cells (3 different cell lines), BA/F3 c-Kit787F (3 different cell lines), and untransfected controls were left untreated or stimulated with SCF (100 ng/mL) or IL-3 (5 ng/mL) for 48 hours. Cell survival was measured using annexinV/PI staining. One representative experiment from 4 is shown (*P = 9 × 10−4;**P = 2 × 10−4; ***P = 8 × 10−6).

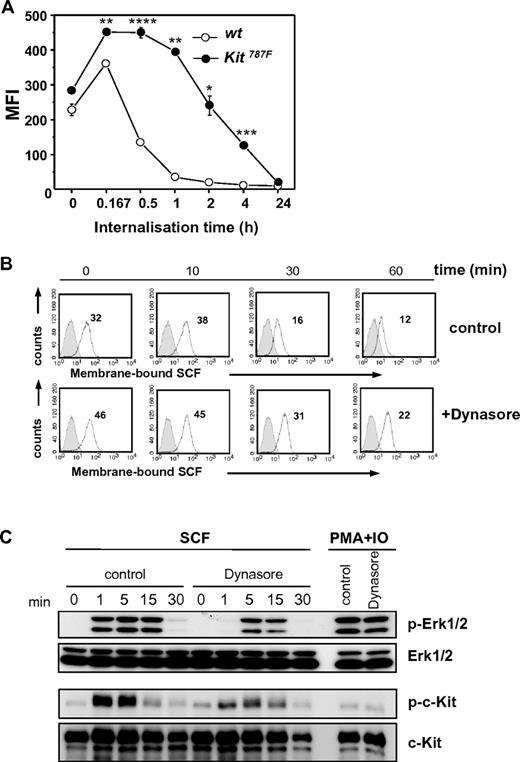

The 787F mutation inhibits SCF-mediated c-Kit internalization

Next, to test whether the 787F mutation affects the internalization of the ligand-receptor complex (SCF-c-Kit), Kit787F and wild-type BMMCs were preincubated with SCF and subsequently stained with anti-SCF–specific antibodies. As shown in Figure 6A, while after 30 minutes of incubation, 63% of bound SCF was internalized by wild-type BMMCs, Kit787F BMMCs internalized only 1% of the bound SCF. A 60% internalization of the SCF-c-Kit complex by Kit787F BMMCs required more than 2 hours of incubation. Even after 4 hours, SCF was still detectable on the surface of Kit787F BMMCs. Comparable results were obtained by detection of c-Kit surface expression levels by flow cytometry over time (supplemental Figure 7). These results indicate that despite comparable SCF binding to c-Kit and normal receptor shedding, the internalization of the SCF-c-Kit complex is impaired in BMMCs carrying the 787F mutation.

SCF-mediated c-Kit internalization and downstream signaling. (A) SCF-c-Kit internalization after SCF binding was measured at indicated time points. BMMCs generated from 3 different wild-type and Kit787F mice were compared. One representative experiment from 3 is shown (*P = .009; **P = .001; ***P = 4 × 10−4;****P = 2 × 10−4). (B) SCF-c-Kit internalization was induced after preincubation of cells with Dynasore (100μM) or DMSO (control) for 30 minutes at 37°C and subsequent loading with SCF (50 ng/mL). αSCF staining (white histograms, MFI indicated) and staining of isotype-matched antibodies of irrelevant specificity (gray histograms) were measured at indicated time points by flow cytometry. One representative experiment from 3 is shown. (C) BMMCs from wild-type mice were preincubated with Dynasore (100μM) or DMSO (control) for 30 minutes at 37°C and stimulated for the indicated times with SCF (100 ng/mL) or PMA and ionomycin. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for (phospho-)Erk1/2, (phospho-)c-Kit, and c-Kit. Immunoblotting with Erk1/2-specific antibodies served as loading control. One representative experiment from 2 is shown.

SCF-mediated c-Kit internalization and downstream signaling. (A) SCF-c-Kit internalization after SCF binding was measured at indicated time points. BMMCs generated from 3 different wild-type and Kit787F mice were compared. One representative experiment from 3 is shown (*P = .009; **P = .001; ***P = 4 × 10−4;****P = 2 × 10−4). (B) SCF-c-Kit internalization was induced after preincubation of cells with Dynasore (100μM) or DMSO (control) for 30 minutes at 37°C and subsequent loading with SCF (50 ng/mL). αSCF staining (white histograms, MFI indicated) and staining of isotype-matched antibodies of irrelevant specificity (gray histograms) were measured at indicated time points by flow cytometry. One representative experiment from 3 is shown. (C) BMMCs from wild-type mice were preincubated with Dynasore (100μM) or DMSO (control) for 30 minutes at 37°C and stimulated for the indicated times with SCF (100 ng/mL) or PMA and ionomycin. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for (phospho-)Erk1/2, (phospho-)c-Kit, and c-Kit. Immunoblotting with Erk1/2-specific antibodies served as loading control. One representative experiment from 2 is shown.

To investigate whether inhibition of c-Kit endocytosis in SCF-stimulated wild-type BMMCs affects c-Kit downstream signaling, wild-type BMMCs were treated with Dynasore, a cell-permeable dynamin inhibitor (Figure 6B-C). The c-Kit internalization was tested by FACS analysis (Figure 6B) and was found to correlate, with slightly different dynamics, with the reduction of Erk1/2 phosphorylation and c-Kit autophosphorylation as determined by Western blot analysis (Figure 6C). Therefore, in wild-type BMMCs, c-Kit endocytosis is required for c-Kit kinase activity supporting the concept that c-Kit signaling is regulated via receptor internalization.

Discussion

Previous studies have provided evidence that loss-of-function mutations in the murine dominant white spotting/c-kit locus affect MC differentiation and function. We have now identified a new c-Kit loss-of-function mutation that confers severe MC deficiency: Kit787F mice lack both mucosal and connective tissue-type MCs. The 787F mutation in BMMCs affects SCF-mediated functions such as cytokine production and apoptosis rescue. Furthermore, the known synergistic effect of SCF on FcεRI-mediated MC activation is impaired by this c-Kit mutation. Interestingly, c-Kit downstream signaling in Kit787F BMMCs is initiated normally, but fails to be sustained thereafter. Finally, we provide evidence that the mechanism responsible for the observed defect in MC differentiation and survival is the inhibition of c-Kit receptor internalization, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. Together, these observations conclusively demonstrate that I787 is essential in regulating c-Kit function and, thereby, MC development and survival. Our study, thus, not only identifies yet another crucial site in the c-Kit receptor protein, whose mutation has grave consequences for MC biology, but also introduces a novel concept namely that sustained c-Kit signaling and receptor internalization are required for MC development, activation, and survival.

A large number of mutations in white spotting locus (W) allelic to c-Kit have been identified. Between them, mutations located upstream the kit transcription start to affect the expression of Kit to a different degree as well as MCs numbers in vivo.31,32 Wsh mice bear an inversion of ∼3.1 Mb inactivating transcriptional regulatory elements 67.5 kb upstream of the c-Kit transcription start,32,33 leading to tissue-specific dysregulation of c-Kit expression. In Wsh mice, all organs lack MCs, with the exception of skin, in which MC numbers decrease in an age-dependent manner.34 The WBB6F1-KitW/KitW-v mouse strain, which is frequently used to study MC functions in vivo and regarded as MC-deficient, is heterozygous for 2 distinct c-Kit mutations—a T660M substitution (KitW-v allele) and a deletion mutation of 78 amino acids resulting in the absence of the transmembrane domain (KitW allele), leading to a block in MC development. F856S substitution within the tyrosine kinase domain in Wads mutant strain is reported to lack MCs specifically and only in the skin.35 Furthermore, amino acid substitutions impairing receptor autophosphorylation (eg, Y567F and Y569F at the juxtamembrane domain) have demonstrated the essential function of these residues in activation of downstream signaling pathways in vitro and MC development in vivo.36 However, only combined mutations of both tyrosine residues resulted in a severe deficiency in SCF-mediated signaling and loss of MCs in the peritoneal cavity, stomach, and dermis, while the single mutations Y719F, Y569F, and Y567F lead to a strong reduction of MC numbers in the peritoneum, but not skin.36-38 In contrast to the above reported mutations, our study reports that the single 787F point mutation alone is sufficient for the complete absence of both connective tissue types and mucosal MCs and underlines the essential regulatory role of this residue in MC development. 787F mutation does not affect c-Kit shedding, induced by phorbol esters,39 indicating that wild-type and 787F c-Kit are comparable in the accessibility for sheddases, which are in charge of cleaving c-Kit. Because induction of CD53, CD54/ICAM expression and histamine production are induced in BAF3 cells transfected with c-Kit bearing the activating mutation D816V,40 we asked whether these markers are down-regulated in 787F BMMCs. However, our data suggest that expression of CD53, CD54/ICAM-1, and histamine do not correlate with inhibitory effects of 787F mutation. Further, we could observe that the expression of MC proteases is not affected by 787F mutation.

The 787F mutation in BMMCs not only affects SCF-mediated functions such as cytokine production and cell survival, but also impairs the synergistic effect of the SCF-c-Kit signaling pathway to FcεRI-mediated signals.

I787 resides in the C-lobe of the kinase and immediately precedes the catalytic loop of the kinase (consisting of the sequence HRDLAARN), which surrounds the actual site of phosphate transfer from ATP to the substrate and could be important for appropriate phosphorylation and tyrosine kinase activity. In addition, the crystal structure of activated c-Kit indicates that I787 could form hydrogen bonds with R815 of the C-lobe, which may serve to stabilize the activation loop in an extended conformation required for kinase activation.12 Interestingly, the 787F mutation does not seem to disrupt the catalytic loop, since early signaling events such as Erk1/2 and p38 phosphorylation take place normally after ligand binding in Kit787F BMMCs. However, sustained signaling is impaired, and receptor internalization is severely decelerated. Therefore our data raise the possibility that receptor internalization is an essential step for sustained c-Kit signaling events, rather than inactivation of ligand-receptor complexes, and that receptor internalization and autophosphorylation are so intimately intertwined that both kinase activity and receptor endocytosis may well operate side-by-side.

Furthermore, the MAPK pathway and the PI3K pathway are reported as distinct pathways regulating proliferation and survival. Namely, they are activated independently of each other downstream of c-Kit in MCs.41,42 However, our study demonstrates that the 787F mutation affects both pathways temporally in a similar manner, both being activated immediately after ligand-mediated engagement of the receptor and impaired in Kit787F BMMCs at later time points.

That the substitution of I787 by phenylalanine in c-Kit is responsible for the defect in SCF-mediated c-Kit signaling was also proven in BA/F3 cells transfected with mutant c-Kit cDNA. BA/F3 c-Kit787F cells show an inhibited Erk1/2 phosphorylation and were not rescued from cell death in response to SCF. Because c-Kit internalization in transfected BA/F3 cells, in comparison to primary MCs takes place at low rate (data not shown), these cells were not suitable to investigate c-Kit internalization dynamics.

Recent studies on signal compartmentalization indicate that receptor endocytosis plays a greater role in cellular biology than merely serving as a degradation pathway. Receptor internalization targets activated receptors to endocytic compartments, where specific signaling complexes can be assembled and/or stabilized.43,44 While MAPK activation by receptor tyrosine kinases is thought to be initiated at the plasma membrane, it has been demonstrated that endosomes support sustained MAPK activation.45,46 Therefore, in future studies it will be essential to examine in detail which of the c-Kit-induced signaling pathways are dependent on receptor internalization.

Finally, identification of small molecule mimetics of the I787 region could be a novel approach for developing c-Kit antagonists that are of importance for the treatment of patients with aberrant c-Kit tyrosine kinase activity, but do not target the conventional kinase active site. This appears all the more important since the D816V mutant of c-Kit frequently observed in systemic mastocytosis patients is resistant to treatment with STI-571 (Gleevec, imatinib). Targeting c-Kit may also be relevant in MC-associated disorders in which SCF acts as an amplifier of antigen-mediated cell activation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Manuel Hein, Kathrin Westphal, Katrin Streeck, Gesine Rohde, and Marlies Kaufmann for excellent technical support, Elena Bulanova for helpful discussion, and Nora Smart for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; SFB/TR22 A14 to S.B.P and HU794/4-2 to M.H). P.R. is supported by Clusters of Excellence “Future Ocean” and “Inflammation at Interfaces.”

Authorship

Contribution: Z.O., N.F., M.H., J.M., F.M., M.S., P.R., and A.B. performed the research; X.D. and B.A.B. contributed the mice; T.G. contributed to the histologic analyses; and Z.O., N.F., and S.B.P. analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Silvia Bulfone-Paus, Department of Immunology and Cell Biology, Research Center Borstel, Parkallee 22, D-23845 Borstel, Germany; e-mail: sbulfone@fz-borstel.de; or Zane Orinska, Department of Immunology and Cell Biology, Research Center Borstel, Parkallee 22, D-23845 Borstel, Germany; e-mail: zorinska@fz-borstel.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal