Abstract

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) plays a critical role in the natural history of human plasma cell neoplasms (PCNs), such as plasma cell myeloma and plasmacytoma (PCT). IL-6 is also at the center of neoplastic plasma cell transformation in BALB/c (C) mice carrying a transgene, H2-Ld-IL6, that encodes human IL-6 under control of the major histocompatibility complex H2-Ld promoter: strain C.H2-Ld-IL6. These mice are prone to PCT, but tumor development is incomplete with long latencies (∼ 40% PCT at 12 months of age). To generate a more robust mouse model of IL-6–dependent PCN, we intercrossed strain C.H2-Ld-IL6 with strains C.iMycEμ or C.iMycCα, 2 interrelated gene-insertion models of the chromosomal T(12;15) translocation causing deregulated expression of Myc in mouse PCT. Deregulation of MYC is also a prominent feature of human PCN. We found that double-transgenic C.H2-Ld-IL6/iMycEμ and C.H2-Ld-IL6/iMycCα mice develop PCT with full penetrance (100% tumor incidence) and short latencies (3-6 months). The mouse tumors mimic molecular hallmarks of their human tumor counterparts, including elevated IL-6/Stat3/Bcl-XL signaling. The newly developed mouse strains may provide a good preclinical research tool for the design and testing of new approaches to target IL-6 in treatment and prevention of human PCNs.

Introduction

Plasma cell myeloma (PCM), plasmacytoma (PCT), and immunoglobulin (Ig) deposition diseases belong to a clinically and pathogenetically diverse group of human plasma cell neoplasms (PCNs) composed of fully transformed, Ig-producing B lymphocytes that have undergone terminal differentiation to plasmablasts and plasma cells. Prognosis and outcome of PCM, commonly known as multiple myeloma (MM)—the most prevalent and fatal PCN and the second most common hematologic malignancy worldwide—remain grim despite availability of sophisticated conventional treatment protocols (chemotherapy, irradiation, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) that have been recently supplemented by novel targeted therapies including proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib), immunomodulatory agents (thalidomide, lenalidomide), antibodies to interleukin-6 (IL-6) or its receptor, and a variety of newly emerging inhibitors of cellular signal transduction pathways.1 Mouse models of human PCNs may afford a genetically defined and environmentally controlled preclinical research tool for the design and testing of new approaches to prevent, treat, and eventually cure PCM.2 Furthermore, studies of PCNs in laboratory mice may permit—in ways difficult to pursue in human beings—elucidation of the biologic mechanisms by which PCNs originate, progress, and acquire therapy resistance. These considerations underlie the strong rationale to continue with basic research efforts to design new mouse models of PCNs that accurately reproduce important genetic and phenotypic features of their neoplastic human counterparts.

Since spontaneous PCNs in laboratory (and wild) mice are rare,3 efforts have been undertaken to genetically engineer inbred strains of laboratory mice for increased proclivity to malignant plasma cell transformation. The first success along this line took advantage of a v-Abl transgene (TG) expressed in B-lineage cells under control of the intronic immunoglobulin heavy-chain (Igh) enhancer, Eμ.4 Subsequent approaches relied on TGs, such as Eμ-Bcl25 and Eμ-Bcl-XL,6 that protect incipient plasma cell tumors from programmed cell death (apoptosis). A somewhat unexpected opportunity is afforded by mice harboring a TG fusion gene, NPM-ALK,7 originally identified as the hallmark mutation of the human T-cell neoplasm, anaplastic large cell lymphoma. A recent, exciting advance is the development of strain Vk*MYC, which is prone to PCM-like tumors induced by a conditional (silent) MYC TG that can be activated in germinal center (GC) B cells upon expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID).8 Additional work is warranted to sort out the strengths and limitations of existing TG mouse models and to translate insights gleaned from individual models into tangible benefits for patients with PCNs. Equally important may be the development of new strains that recapitulate PCN traits not produced thus far.

One hallmark of human PCN yet to be adequately modeled in mice is the collaboration of the proinflammatory cytokine, interleukin 6 (IL-6), with the pleiotropic oncogenic transcription factor, MYC. Toward that goal, we have reported that BALB/c (C) mice carrying a human IL-6 TG driven by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) H2-Ld promoter develop PCT with incomplete penetrance and long latency (approximately 40% tumors by 12 months of age).9 The tumors arise predominantly in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and contain in most cases,9 but not all,10 a chromosomal T(12,15) translocation that results in the deregulated expression of the Myc oncogene due to juxtaposition of the protein-encoding portion of Myc to enhancers in the Igh locus. In related studies, we used gene targeting in mice to recapitulate 2 different fine structures of the T(12,15) translocation repeatedly detected in IL-6 TG GALT PCT9 and inflammation-dependent peritoneal PCT of strains C11 and C.Bcl2.5 This effort resulted in the generation of 2 mouse strains, designated iMycEμ and iMycCα, that contain the same His6-tagged mouse Myc cDNA gene inserted upstream of the intronic Igh enhancer, Eμ,12 and the 3′ Igh enhancer, Eα,13 respectively. In addition to the mouse PCT T(12,15) translocations, the iMycEμ and iMycCα TG mice (hereafter referred to collectively as iMyc mice) mimic the human t(8;14)(q24;q32) translocation that juxtaposes Eμ or Eα to MYC in the human post-GC B-cell tumor, Burkitt lymphoma.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that an intercross of the H2-Ld–IL6 and iMyc TGs on the genetic background of strain C would yield robust mouse models of neoplastic plasma cell transformation of value for the evaluation of the IL-6/MYC cooperativity in human PCNs. Our experimental strategy consisted of 2 principal steps. The first involved backcross of iMycEμ and iMycCα TGs from the mixed genetic background of the original gene-targeted strain (segregating C57BL/6 and 129/SvJ alleles)13 onto the genetic background of strain C. The fully backcrossed (congenic) strains were designated C.iMycEμ and C.iMycCα. The rationale for this approach was the well-documented genetic susceptibility of strain C to PCT, which is caused, in part, by weak efficiency alleles of Cdkn1a, which encodes p16Ink4a,14 and Frap.15 Consistent with that unique susceptibility, transfer of iMycEμ12 for 4 generations onto strain C (N4) greatly enhanced the incidence, and accelerated the onset, of peritoneal PCT.16,17 The second step entailed an intercross of strain C.H2-Ld-IL6 with strains C.iMycEμ or C.iMycCα, thus generating double-TG C.H2-Ld-IL6/iMycEμ or C.H2-Ld-IL6/iMycCα mice, which, for the sake of brevity, will henceforth be referred to C.IL6/iMycEμ or C.IL6/iMycCα. When considered collectively, they will be called C.IL6/iMyc.

We found that C.IL6/iMyc mice develop neoplasms with full penetrance (100% tumor incidence), short latencies (3-6 months), and remarkable phenotypic consistency (PCT). Thus, IL-6 and MYC collaborate efficiently in neoplastic plasma cell development in mice. C.IL6/iMyc mice may be useful for elucidating the molecular mechanisms by which IL-6 promotes PCNs in humans. Moreover, these newly developed mouse strains may afford a heretofore unavailable, robust, preclinical research tool for validation of new treatment and prevention approaches that target IL-6 in human PCNs.

Methods

Mice

Strains iMycEμ12 and iMycCα13 contain a mouse Myc cDNA inserted into different sites in the mouse Igh locus, as described previously. Both the iMycEμ and iMycCα TG were backcrossed for more than 12 generations onto strain C to generate C.iMycEμ and C.iMycCα congenics. The generation and use of strain C.IL6 for research on the natural history of PCNs has been described.9,18 Double-TG C.IL6/iMyc mice were selected from crosses between heterozygous TG C.iMyc and heterozygous TG C.IL6 mice based on genotyping of the progeny. All animal studies were approved under University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Protocol 0006A56361.

Tumor diagnosis, classification, and transplantation

Mice were monitored weekly for development of splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy and were necropsied when moribund. Tissues obtained at necropsy were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Neoplasms were categorized according to the Bethesda classification of mouse lymphoid neoplasms.19 Photomicroscopic images were acquired using an Olympus AH-2 Vanox-S microscope equipped with an Olympus DP70 cooled digital color camera system and the following dry (air) plan achromatic objectives (magnification/numerical aperture): 1×/0.04, 2×/0.02, 4×/0.16, 10×/0.4, 20×/0.7, 40×/0.95. Raw images were saved in tagged image file (TIF) format and imported into the Adobe Photoshop CS2 Version 9.0.2 software package for image enhancement. This consisted of automatic adjustments of image level, image contrast, and image color, in that sequence, followed by saving in CMYK color mode. The mitotic index was determined from studies of 5 randomly chosen microscopy fields (diameter 0.159 mm) using a ×40 objective and ×10 ocular. Tissues from young, tumor-free mice were diagnosed as exhibiting premalignant plasma cell accumulations based on the following gradient of increasing abnormality: plasmacytosis, an accumulation of normal-appearing, nondividing plasma cells; plasma cell hyperplasia, a mixture of normal and aberrant, hyperchromatic, sometimes mitotically active plasma cells; and microplasmacytoma, isolated clusters of malignant-appearing plasma cells, presumptive precursors of overt PCT. Frank neoplasms from C.IL6/iMyc mice were passaged by intravenous or intraperitoneal transfer of 2 × 106 to 10 × 106 cells to pristane-primed C mice as previously described.9

Detection of serum paraproteins and immunolabeling of cytoplasmic Ig in tumor cells

Identification of serum paraproteins and Ig isotypes was performed as described previously. Cytoplasmic Ig in malignant plasma cells was detected by immunohistochemistry as described elsewhere.16

Immunoblotting

Whole-tissue protein extracts were prepared from snap-frozen tumor samples. Protein (30 μg/lane) was separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to Protran nitrocellulose membranes, probed with Ab and detected by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary Ab using an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) kit. Ab and cell extracts used in these studies are detailed in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Isolation of splenic B cells

Normal splenic B cells were purified using the MACS B220 mouse B-cell sorting kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Recovery of B cells from single-cell suspensions prepared from whole spleen was approximately 20%. The purity of separated B cells was greater than 90% as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (data not shown).

Global gene expression profiling

Sample preparation, hybridization, and microarray analysis were performed as previously described.20 Gene chips comprised approximately 18 000 mouse genes represented by 70mer oligonucleotides. Raw datasets were normalized using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing function in R package. Significant genes were identified with the assistance of SAM (significance analysis of microassays) and then hierarchically clustered using Genesis. All microarray data can be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) public database21 under accession number GSE19336.

Results

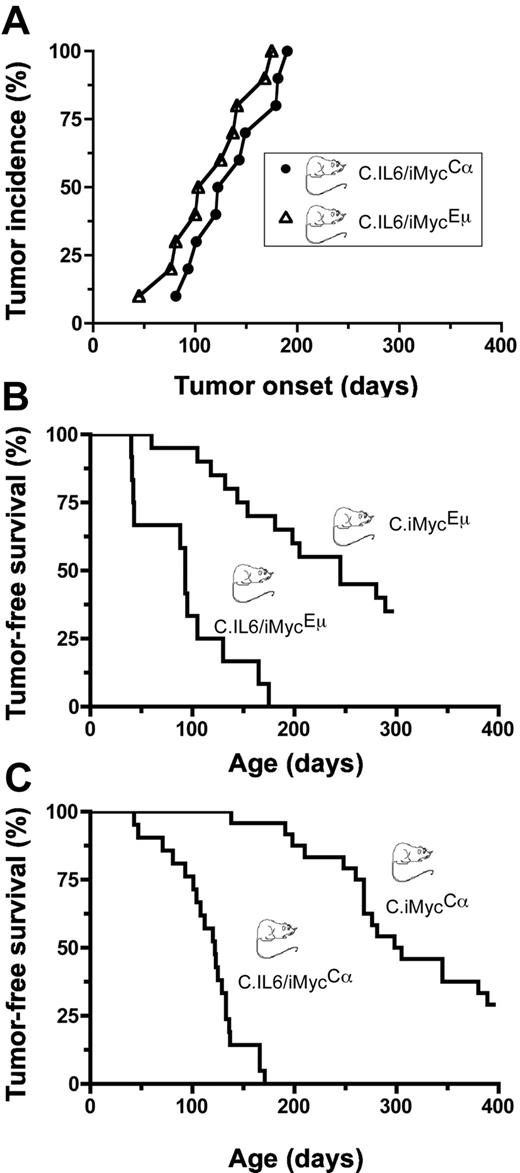

Development of PCT in a pilot study of C.IL6/iMyc mice

To determine whether deregulated expression of both IL-6 and MYC in double-TG mice would act synergistically in plasma cell transformation, we crossed C.IL6 mice with strains C.iMycEμ and C.iMycCα. A total of 10 double-TG mice of both genotypes were monitored at weekly intervals for signs of tumor development manifested by splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy; all C.IL6/iMycEμ and C.IL6/iMycCα mice developed tumors before 200 days of age (Figure 1A). Tumor diagnosis was confirmed by histologic studies of tissues obtained at necropsy. The median age of tumor onset was 115 days plus or minus 41.7 days (range, 45-175 days) for C.IL6/iMycEμ mice and 136 days plus or minus 38.8 days (range, 81-190 days) for C.IL6/iMycCα mice, a statistically insignificant difference (P = .389; log-rank test). Histologic studies of 5 tumors from both groups were uniformly positive for homogenous sheets of plasma cells that contained varying amounts of cytoplasm and eccentric nuclei with marginated chromatin (“clock-face” appearance) and prominent nucleoli. Based on these features, the tumors were classified as PCT. Compared with the reported incidence and latencies for PCT in C mice bearing only the IL-6 TG (∼ 40% tumors by 12 months of age; n = 45),9 the preliminary results with double-TG C.IL6/iMyc mice suggested that the iMyc TGs greatly accelerated PCT development when expressed in concomitance with deregulated IL-6.

Incidence and onset of PCT. (A) Pilot study of tumor development in C.IL6/iMycEμ (▵) and C.IL6/iMycCα (○; n = 10 for both genotypes). (B) Survival studies of C.IL6/iMycEμ mice (n = 12) and C.iMycEμ mice (n = 20). Tumors arising in C.IL6/iMycEμ mice were invariable PCT. Most tumors developing in C.iMycEμ mice were high-grade B-cell lymphoma. (C) Survival studies of C.IL6/iMycCα mice (n = 21) and C.iMycCα mice (n = 24). All tumors in C.IL6/iMycCα mice were PCT. Most tumors from C.iMycCα mice were high-grade B-cell lymphoma. Transfer of the iMycCα TG from the original, mixed background that exhibited approximately 9% of tumors by 12 months of age13 onto strain C caused a dramatic increase in tumor incidence with minimal impact on tumor phenotype.

Incidence and onset of PCT. (A) Pilot study of tumor development in C.IL6/iMycEμ (▵) and C.IL6/iMycCα (○; n = 10 for both genotypes). (B) Survival studies of C.IL6/iMycEμ mice (n = 12) and C.iMycEμ mice (n = 20). Tumors arising in C.IL6/iMycEμ mice were invariable PCT. Most tumors developing in C.iMycEμ mice were high-grade B-cell lymphoma. (C) Survival studies of C.IL6/iMycCα mice (n = 21) and C.iMycCα mice (n = 24). All tumors in C.IL6/iMycCα mice were PCT. Most tumors from C.iMycCα mice were high-grade B-cell lymphoma. Transfer of the iMycCα TG from the original, mixed background that exhibited approximately 9% of tumors by 12 months of age13 onto strain C caused a dramatic increase in tumor incidence with minimal impact on tumor phenotype.

Accelerated PCT in C.IL6/iMyc mice relative to C.iMyc mice

To confirm and extend the study described here, we performed a controlled side-by-side comparison of tumor-free survival in C.IL6/iMyc and C.iMyc mice. We found that 12 (100%) of 12 C.IL6/iMycEμ mice and 13 (65.0%) of 20 C.iMycEμ mice developed tumors by 300 days of age (Figure 1B). Median tumor-free survival of double-TG mice (93 days; range, 40-175 days) was reduced by a statistically significant factor of 2.63 compared with single-TG mice (245 days; range, 60-289 days; P < .001 by log-rank test). In striking parallel, we found that 21 (100%) of 21 C.IL6/iMycCα mice and 17 (70.8%) of 24 C.iMycCα mice developed tumors by 400 days of age (Figure 1C), with median tumor-free survivals of 122 days (range, 43-171 days) versus 228 days (range, 138-389 days), respectively, a highly significant 2.2-fold difference by log-rank analysis (P < .001). These results demonstrated that in C mice, deregulated expression of MYC, driven by either of the iMyc TG, collaborates with constitutive expression of IL-6 to induce PCNs in all double-TG mice with latencies of less than 200 days.

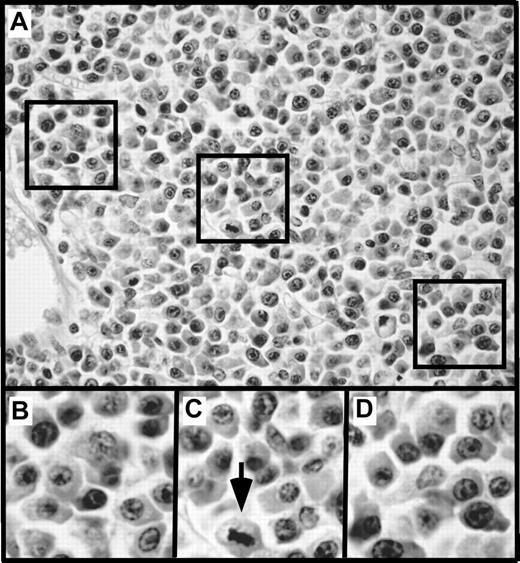

Histopathologic features and transplantation of PCT

Histologic studies of tissues from 12 C.IL6/iMycEμ mice and 15 C.IL6/iMycCα mice yielded a diagnosis of PCT in all cases. According to the 3 distinct subtypes of PCT described in the Bethesda proposals,19 10 (83.3%) of 12 C.IL6/iMycEμ tumors were categorized as plasmablastic PCT and 2 (16.7%) were classified as plasmacytic PCT. A total of 9 (60%) of 15 C.IL6/iMycCα tumors were diagnosed as plasmacytic, and 6 (40%) of 15 were diagnosed as plasmablastic. The plasmacytic tumors (Figure 2A-B) were composed of mature plasma cells with a low mitotic index (∼ 5 mitotic figures/high-power field [hpf]). The plasmablastic tumors (Figure 2 bottom panels) consisted of somewhat larger cells with a higher nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, large nuclei containing fine chromatin and prominent nucleoli, and a high mitotic index (approximately 12 mitotic figures/hpf). FACS analysis of tumor cells and immunostaining of tumor sections (data not shown) showed that both plasmacytic and plasmablastic tumor cells expressed CD138 (syndecan 1). Interestingly, less well-differentiated plasma cell tumors, designated anaplastic PCT (APCT),20 were not seen among the C.IL6/iMyc cases studied here.

Histopathology of PCT. (A) Mesenteric lymph node containing a plasmacytic PCT. Residual follicles, such as the one indicated by arrowheads, are displaced by large interfollicular expansions of mature plasma cells. (B) High-power view of the interfollicular area containing aberrant, yet relatively small, plasma cells with varying amounts of cytoplasm. (C) Small bowel mucosa harboring a plasmablastic PCT with sheets of abnormal plasma cells infiltrating the mucosa. (D) High-power view showing atypical, large plasma cells with pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and varying amounts of cytoplasm, consistent with the diagnosis of plasmablastic PCT. Original magnification: ×4 (A,C) and ×40 (B,D). Final magnification: ×10 (A,C) and ×100 (B,D).

Histopathology of PCT. (A) Mesenteric lymph node containing a plasmacytic PCT. Residual follicles, such as the one indicated by arrowheads, are displaced by large interfollicular expansions of mature plasma cells. (B) High-power view of the interfollicular area containing aberrant, yet relatively small, plasma cells with varying amounts of cytoplasm. (C) Small bowel mucosa harboring a plasmablastic PCT with sheets of abnormal plasma cells infiltrating the mucosa. (D) High-power view showing atypical, large plasma cells with pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and varying amounts of cytoplasm, consistent with the diagnosis of plasmablastic PCT. Original magnification: ×4 (A,C) and ×40 (B,D). Final magnification: ×10 (A,C) and ×100 (B,D).

At necropsy, all C.IL6/iMyc tumors were characterized by significant enlargement of the mesenteric lymph node, with spleen weights of up to 1.5 g. Increases in GALT in some cases resulted in intestinal obstruction due to intussusception. Among peripheral lymph nodes, those in the cervical and axillary regions were often larger than those draining the lower extremities. The regular presence of neoplastic plasma cells in blood vessels, diagnostic of plasma cell leukemia, was consistent with generalized tissue involvement including liver, kidney, lung, and bone marrow (data not shown).

As another assessment of transformation, immunocompetent C mice primed 1 to 4 weeks previously with pristane were inoculated intraperitoneally with approximately 5 × 106 cells from tumor-bearing tissues of 12 C.IL6/iMyc mice diagnosed histologically with PCNs. All recipients died within 4 to 6 weeks with widely disseminated disease, indicating that the tumors were highly malignant.

Production of monoclonal Ig

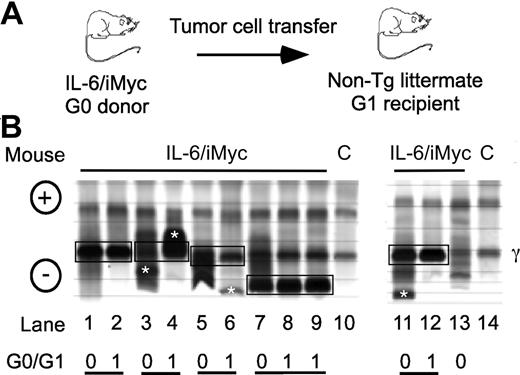

In parallel to previous findings with PCT-bearing mice,9,13,16 electrophoretic fractionation of serum proteins from C.IL6/iMyc mice with tumors revealed the presence of prominent “M-spikes” indicative of monoclonal Ig paraproteins, usually on the background of a marked polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analyses of Ig isotypes of paraproteins in sera from 8 C.IL6/iMycEμ and 6 C.IL6/iMycCα tumors identified 7 as IgG1, 4 as IgG2a, and 3 as IgG2b (data not shown). The isotypes characteristic of individual primary tumors (G0) were also present in sera of first-generation (G1) recipients of primary tumor cells (Figure 3A). The electrophoretic patterns of 5 different pairs of G0/G1 sera are illustrated in Figure 3B. These findings demonstrated that primary PCT from C.IL6/iMyc mice preferentially expressed IgG isotypes and that these were maintained on transplantation. Interestingly, the dominance of IgG-producing PCT in C.IL6/iMyc mice is distinct from the overrepresentation of IgA-producing PCT in pristane-treated C mice, and resembles more closely the isotype distribution seen in spontaneous PCT from C.IL6 mice9 and pristane-induced PCT from New Zealand Black (NZB) mice.3

Detection of serum paraproteins in sera of PCT-bearing mice. (A) Sera are from C.IL6/iMyc primary PCT (G0 samples) or tumor cell transplant recipients (G1 samples). (B) Paired G0/G1 samples from C.IL6/iMycEμ mice (lanes 1-4 and lane 13) or C.IL6/iMycCα mice (lanes 5-9 and 11-12). Lanes 10 and 14 contain samples from normal mice used as control. Paired G0 and G1 samples with shared M components are indicated by joined black boxes. M components only present in the G0 or G1 sample are indicated by white asterisks. The position of the γ protein band is indicated to the right and the anode/cathode to the left. C indicates serum from a control non–tumor-bearing mouse.

Detection of serum paraproteins in sera of PCT-bearing mice. (A) Sera are from C.IL6/iMyc primary PCT (G0 samples) or tumor cell transplant recipients (G1 samples). (B) Paired G0/G1 samples from C.IL6/iMycEμ mice (lanes 1-4 and lane 13) or C.IL6/iMycCα mice (lanes 5-9 and 11-12). Lanes 10 and 14 contain samples from normal mice used as control. Paired G0 and G1 samples with shared M components are indicated by joined black boxes. M components only present in the G0 or G1 sample are indicated by white asterisks. The position of the γ protein band is indicated to the right and the anode/cathode to the left. C indicates serum from a control non–tumor-bearing mouse.

Clonal diversification

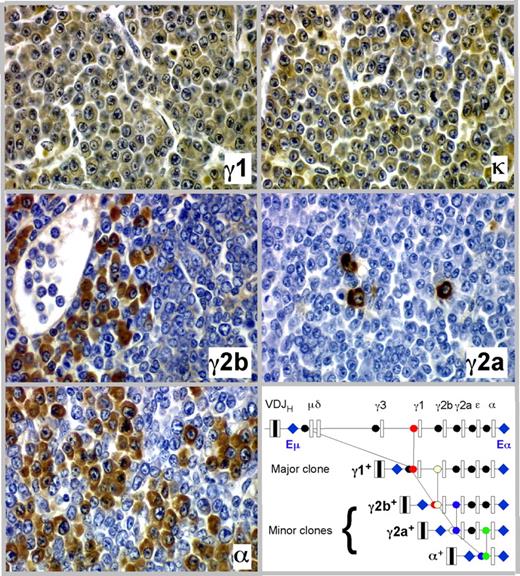

The detection of minor M-spikes paired with dominant bands in sera from tumor-bearing C.IL6/iMyc mice (eg, Figure 3B lanes 3, 6, and 11) was consistent with the presence of more than one Ig-secreting clone in the same mouse. Our previous studies of pristane-induced PCT in C mice22 showed that the minor bands might mark the presence of cell clones generated by the process of class switch recombination (CSR) as progeny of a “parental” dominant clone. In keeping with this suggestion, we found that PCT of C.IL6/iMyc mice frequently undergo CSR in vivo, yielding subclones that express a CH locus 3′ to that of the parental clone. Figure 4 presents a detailed analysis of one tumor from a C.IL6/iMycCα mouse showing serial tissue sections immunostained with Ab specific for Ig heavy-chain isotypes and light chains. More than 90% of tumor cells expressed γ1 heavy chain and κ light chain (Figure 4 top panels), the phenotype of the dominant clone (IgG1). Accompanying and embedded within the dominant clone were populations of tumor cells that were smaller in number than the γ1 clone that expressed γ2a, γ2b, and α heavy chains (Figure 4 center panels and bottom left). These isotype variants were usually clustered, suggesting their origin from single switched cells, but on sections stained with H&E they were indistinguishable from cells expressing alternative isotypes, such that they would not have been identified without immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. As cartooned in the molecular scheme portrayed in the bottom right panel of Figure 4, we postulate that the subclones expressing γ2a, γ2b, and α were derived by CSR from the “parental clone” that expressed γ1. Thus, of the 4 CH loci located downstream of Cγ1, 3 were used in clonal diversification of this particular PCT. Importantly, results similar to those presented in Figure 4 were obtained with 2 additional tumors from C.IL6/iMycEμ and 2 from C.IL6/iMycCα mice (data not shown). These findings indicate that CSR is a common molecular diversification mechanism of plasma cell tumors in C.IL6/iMyc mice and reflects the continued activity of AID in these neoplasms.

Clonal diversification of PCT by isotype switching in situ as shown by serial tissue sections of a PCT that arose in a C.IL6/iMycCα mouse. Ig heavy-chain–producing tumor cells or κ light-chain–producing tumor cells (top right) are immunolabeled in brown, using isotype-specific antibodies (original magnification, ×40). The bottom right panel presents a molecular scheme on the putative derivation of the γ2a+, γ2b+, and α+ subclones from the parental γ1+ clone. The possibility that CSR to Cϵ also occurred was not examined, but is an extremely rare event in other studies of PCT.

Clonal diversification of PCT by isotype switching in situ as shown by serial tissue sections of a PCT that arose in a C.IL6/iMycCα mouse. Ig heavy-chain–producing tumor cells or κ light-chain–producing tumor cells (top right) are immunolabeled in brown, using isotype-specific antibodies (original magnification, ×40). The bottom right panel presents a molecular scheme on the putative derivation of the γ2a+, γ2b+, and α+ subclones from the parental γ1+ clone. The possibility that CSR to Cϵ also occurred was not examined, but is an extremely rare event in other studies of PCT.

Changes in cellular signaling pathways

To develop an understanding of the molecular mechanism that might underlie the collaboration of IL-6 and MYC in the genesis of PCT in double-TG mice, we used Western blotting to screen for changes in cellular signaling pathways known to contribute to cell growth, proliferation, and survival programs in plasma cell tumors—IL-6-Stat3-Bcl-XL, PI3K-AKT, Ras-MAPK, and Myc-p19Arf-p53 (Figure 5A)—comparing PCT from C.IL6/iMyc and C.IL6 mice. The “iMyc-only” tumors were excluded from these comparisons because they comprise high-grade B-cell lymphomas (supplemental Figure 1) rather than PCT.

Analysis of signal transduction pathways comparing PCT from C.IL6/iMyc and C.IL6 mice. (A) Schematic overview of signaling pathways chosen for Western blot analyses (B-D). (B-D) Lane numbers correspond to normal splenic B cells (lane 1), PCT from C.IL6 mice (lanes 2-5), PCT from C.IL6/iMyc mice (lanes 6-12, with 3 tumors [lanes 6-8] contained on the blot shown to the left and 4 tumors [lanes 9-12] contained on the blot shown to the right), and commercial positive control (lane 13). Loading of equal protein amounts was documented individually for each Western blot by demonstrating comparable levels of β-actin in all lanes; only one example is shown (D bottom). Pathway screening included IL-6/STAT3/Bcl-XL (B), RAS/ERK (C), and MYC/p19/MDM2/p53 (D).

Analysis of signal transduction pathways comparing PCT from C.IL6/iMyc and C.IL6 mice. (A) Schematic overview of signaling pathways chosen for Western blot analyses (B-D). (B-D) Lane numbers correspond to normal splenic B cells (lane 1), PCT from C.IL6 mice (lanes 2-5), PCT from C.IL6/iMyc mice (lanes 6-12, with 3 tumors [lanes 6-8] contained on the blot shown to the left and 4 tumors [lanes 9-12] contained on the blot shown to the right), and commercial positive control (lane 13). Loading of equal protein amounts was documented individually for each Western blot by demonstrating comparable levels of β-actin in all lanes; only one example is shown (D bottom). Pathway screening included IL-6/STAT3/Bcl-XL (B), RAS/ERK (C), and MYC/p19/MDM2/p53 (D).

PCT of C.IL6 mice (Figure 5B “STAT3” lanes 2-5) expressed lower levels of STAT3 than PCT of IL6/iMyc mice (lanes 6-12). In contrast to normal splenic B cells (Figure 5B lane 1), phosphorylated forms of STAT3, pSTAT3Y705 and pSTAT3S727, were readily detected in tumors from mice of both genotypes (Figure 5B “pSTAT3Y705” and “pSTAT3S727”) with levels somewhat higher in PCT from double-TG mice (Figure 5B lanes 6-12) than those from IL-6 TG mice (Figure 5B lanes 2-5). Consistent with these observations, we found higher amounts of Bcl-XL in tumors of double-TG mice relative to single-TG mice (Figure 5B “BCL-XL”). Bcl2l1, which encodes Bcl-XL, is a known transcriptional target of IL-6 and defines a classic survival pathway in PCNs of humans and mice.13 In tumors of C.IL6/iMyc mice, the ratio of Bcl-XL to Bcl-2 expression was clearly shifted toward the former (Figure 5B compare “BCL-XL” and “BCL-2”). Parallel studies of a third member of the BCL2 family, MCL1 (Figure 5B “MCL-1”), showed that the IL6/iMyc samples with the highest levels of Bcl-XL (Figure 5B lanes 7 and 9) expressed the lowest levels of MCL1, suggestive of a Bcl-2–like but less pronounced reciprocity for expression with Bcl-XL. Interpreting the relation of MCL1 to Bcl-XL expression is complicated by the fact that Mcl1 encodes a long antiapoptotic isoform (Figure 5B arrow at “L” at bottom right) and a short proapoptotic isoform (Figure 5B “S”).

Among the 3 main branches of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways—JNK, p38, and ERK—the ERK1-p44T202– and ERK2-p42Y204–dependent pathways are widely considered as most important for plasma cell tumors. We therefore focused on ERK signaling and found that the ratio of total protein levels of ERK1 to ERK2 are somewhat higher in PCT than normal B cells (Figure 5C “ERK1”). However, the ratios of ERK1 to ERK2 expression varied little between tumors of single- and double-TG mice. In contrast to total protein, pERK1 and pERK2 were up-regulated relative to normal B cells in all double-TG tumors compared with only one of 4 C.IL-6 TG tumors (Figure 5C lane 2).

There was little if any evidence for increased PI3K/AKT signaling in IL-6– and IL6/iMyc–induced PCT (supplemental Figure 2B). With the exception of the sample shown in supplemental Figure 2B (lane 5), total AKT protein levels were comparably low in all tumors. The levels of pAKTS473 were also low in all tumors. We were unable to detect pAKTT308 in tumor samples despite using different antibodies (data not shown) and having no problems detecting the positive control irrespective of the antibody used. The apparent lack of AKT activation in mouse PCT may define a difference to human PCM.

Deregulated expression of MYC in B-cell lineage tumors is often accompanied by interruption of the p19Arf-MDM2-p53 tumor suppressor pathway, which can be critical to inhibiting MYC-induced B-cell transformation.23 In keeping with this understanding, 3 of 7 iMyc-accelerated tumors, but none of the PCT from single-TG mice, exhibited high levels of p19Arf (Figure 5D “p19ARF”). Elevated amounts of p53 were seen in 2 tumors each of the IL6/iMyc and IL-6 TG groups (Figure 5D “p53”). MYC levels were higher in tumors from C.IL6/iMyc than C.IL6 mice, as would be expected (Figure 5D “MYC”). There was also a tendency toward higher expression of MDM2 in the tumors of C.IL6/iMyc mice (Figure 5D “MDM2”). Curiously, this included the 3 cases that expressed high levels of p19Arf, a negative regulator of MDM2.

Finally, we screened PCT for expression of 3 proapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family: BAX, BAK, and BIM (supplemental Figure 2C). BAX was expressed at equal levels in PCT and normal B cells, whereas BAK was not expressed in either population. Of the 2 latent, non–death-inducing forms of BIM, BIM extralong (BIM-EL) and BIM long (BIM-L), only BIM-EL was expressed in PCT, perhaps at somewhat higher amounts than in normal B cells. More importantly, the death-inducing form of BIM, BIM short (BIM-S), was not expressed in tumors or in normal B cells.

These findings suggested that, compared with IL-6–induced PCT, IL6/iMyc–driven PCT exhibit heightened IL-6-STAT3-Bcl-XL and ERK signaling. Changes in PI3K-AKT and proapoptotic BAK-BAX-BIM signaling were not found. Unlike IL-6 tumors, IL6/iMyc–driven tumors appear to have the potential to engage the p19Arf-MDM2-p53 axis, although the underlying reasons for this engagement have yet to be determined. Up-regulation of Bcl-XL in IL6/iMyc-dependent tumors may be relevant for human PCM because IL-6 protects myeloma cells from FAS-induced apoptosis by virtue of IL-6-JAK-STAT3–induced up-regulation of BCL-XL.24

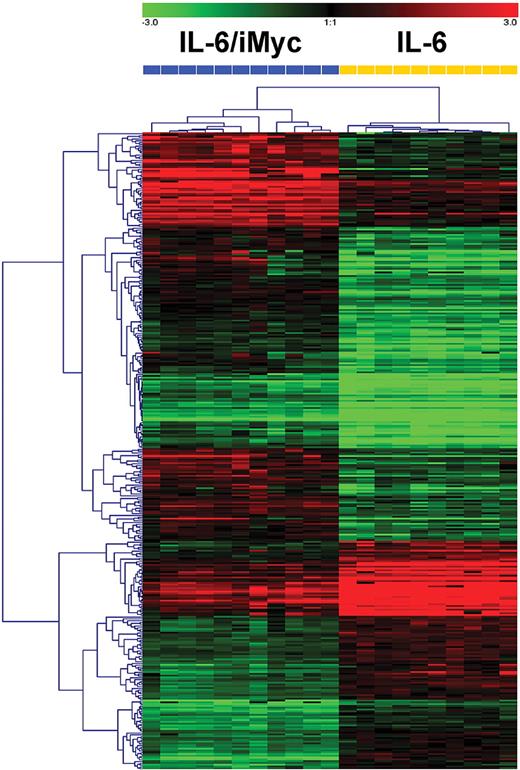

Distinct gene expression profile of IL6/iMyc compared with IL-6–only tumors

Microarray analyses were performed using RNA prepared from PCT (n = 21) of the 2 genotypes. Based on standard hierarchical clustering algorithms, the tumors readily segregated into 2 distinct groups (Figure 6). SAM identified 294 genes that best characterized IL6/iMyc tumors and 211 genes that characterized IL-6–only cases (supplemental Table 2). Genes expressed at increased levels in the IL6/iMyc tumors included a series involved in activation or signaling in the canonical and noncanonical NF-κB pathways:Card11, Ripk4, Map3k2, Nfkbie, and Nfkb2. Others are expressed at increased levels in human MM, the plasma cells of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM), or lymphoplasmactic lymphoma (LPL): Tnfrsf7 (CD27)—MM; Runx2—MM; Zap70—LPL; Akt3—MM; Xrcc2—MM; and Bcl2—MM. The genes encoding CD86 and CD30L, both expressed on stromal cells, may be important for engaging CD28 and variant CD30 proteins on MM cells, respectively, thereby promoting myeloma cell survival. Additional genes and selected references for the genes mentioned here are presented in supplemental Table 3. Among genes expressed at lower levels in IL-6–only tumors were Setd2, which, upon overexpression, facilitates transcription of many p53 targets; Traf4, which, when down regulated, inhibits CD40L-induced apoptosis of MM cells; and Fos, whose expression level increases in the course of myeloma progression. Down-regulation of Ube2b, which is critical to postreplicative DNA damage repair, might contribute to the chromosomal anomalies characteristic of both mouse PCT and human PCM (see supplemental Table 3 for selected references of genes down-regulated in IL-6–only tumors). Although additional studies are warranted before any of these changes can be implicated in the natural history of PCT, these results support our contention that the MYC transcriptional program interacts synergistically with IL-6–driven signaling to drive neoplastic plasma cell transformation.

Hierarchical clustering of PCT from C.IL6/iMyc mice (n = 11) and C.IL6 mice (n = 10) based on global gene expression analysis. Dendrogram at the top shows the samples studied, and their relationships based on similarities in gene expression. C.IL6/iMyc samples included 7 primary (G0) and 4 transplanted (2 G1, 2 G2) tumors. Dendrogram at the left shows the expression patterns of genes across all samples with intensities depicted according to the color scale at the top. The bars above the heat map are color-coded according to genotype and labeled with array numbers.

Hierarchical clustering of PCT from C.IL6/iMyc mice (n = 11) and C.IL6 mice (n = 10) based on global gene expression analysis. Dendrogram at the top shows the samples studied, and their relationships based on similarities in gene expression. C.IL6/iMyc samples included 7 primary (G0) and 4 transplanted (2 G1, 2 G2) tumors. Dendrogram at the left shows the expression patterns of genes across all samples with intensities depicted according to the color scale at the top. The bars above the heat map are color-coded according to genotype and labeled with array numbers.

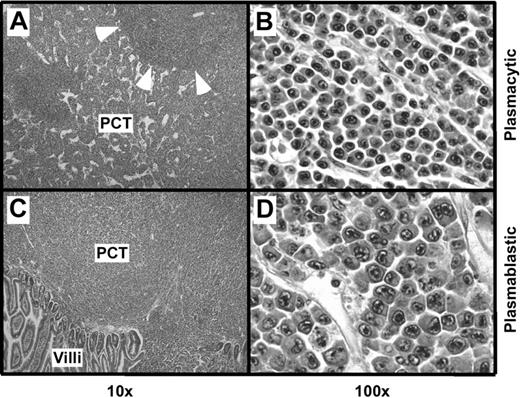

Plasma cell hyperplasia in tumor-free C.IL6/iMyc mice

To gain insight into changes that develop in mice before the onset of clonal malignancies, we performed a comprehensive histologic analysis of 4- to 6-week-old C.IL6/iMycEμ and C.IL6/iMycCα mice, 5 of each genotype. All 10 mice exhibited pronounced plasma cell hyperplasia, similar to that seen preceding GALT-associated PCT of IL-69 and iMycEμ16 TG mice, except that the abnormal accumulation of plasma cells in strain C.IL6/iMyc occurred earlier and more extensively than in the other mice. A representative image of the plasma cell hyperplasia characteristic of C.IL6/iMyc mice is shown in Figure 7.

Plasma cell hyperplasia in young, tumor-free C.IL6/iMyc mice. (A) Low-power view of an abnormal accumulation of plasmablasts and plasma cells in an enlarged peripheral lymph node of a 4-week-old C.IL6/iMycCα mouse (H&E stain; original magnification, ×20; final magnification, ×50). The 3 areas indicated by squares are shown below at higher power (final magnification, ×100; B-D). The arrow in panel C denotes cell that is undergoing division.

Plasma cell hyperplasia in young, tumor-free C.IL6/iMyc mice. (A) Low-power view of an abnormal accumulation of plasmablasts and plasma cells in an enlarged peripheral lymph node of a 4-week-old C.IL6/iMycCα mouse (H&E stain; original magnification, ×20; final magnification, ×50). The 3 areas indicated by squares are shown below at higher power (final magnification, ×100; B-D). The arrow in panel C denotes cell that is undergoing division.

To examine the accumulation of plasma cells in a more quantitative fashion than assessable by histology, we performed FACS analysis of bone marrow and spleen cells from 4-week-old C.IL6/iMyc mice, using non-TG littermates as controls. The frequencies of mature B220−CD138+ plasma cells were less than 1% among bone marrow cells of C.IL6/iMyc and littermate mice, but the frequencies of B220+CD138+ plasmablasts were increased almost 3.5-fold for double-TG mice: 15.6% versus 4.5%, respectively (supplemental Figure 3). This was reminiscent of the distinct population of bone marrow plasmablasts seen in the iMycCα/Bcl-XL model of plasma cell neoplasia.13 The C.IL6/iMyc mice also had grossly elevated numbers of splenic plasmablasts (20.7%) and plasma cells (17.5%) compared with the populations in spleens from control mice (7.2% plasmablasts and approximately 0.5% plasma cells; supplemental Figure 3).

These results suggested that IL-6 and iMyc act synergistically to expand populations of plasmablasts and plasmacytes as targets for the subsequent genetic and epigenetic changes that drive plasma cell transformation.

Discussion

IL-6 is a pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine that not only orchestrates a wide range of vital physiologic functions, but also influences the development of many types of solid tumors and hematopoietic neoplasms. Prominent among the latter are mature B cell–lineage tumors, including Hodgkin lymphomas, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and PCNs.25 In human PCM, IL-6 has long been recognized as a major growth, differentiation, and survival factor for myeloma cells, and as a potent stimulator of osteoclasts, tumor bystander cells involved in myeloma bone disease.26 In mice, IL-6 is firmly linked to inflammation-induced peritoneal PCT, which are readily induced in strains C and NZB by pristane, a poorly metabolized isoalkane that provokes the formation of inflammatory granulomas, a rich source of IL-6 at the site of tumor development.27 Critical evidence for the involvement of IL-6 in inflammation-induced peritoneal plasmacytomagenesis was first obtained in studies with C mice, showing that tumor growth is enhanced by exogenous IL-6 but inhibited by antibodies to IL-6 or its receptor.28 Subsequent work demonstrated that C mice homozygous for a null allele of Il6 are resistant to both pristane-induced peritoneal PCT29 and peritoneal PCT accelerated by a Myc/Raf retrovirus.30 Conversely, C mice carrying the H2-Ld-IL6 TG develop PCT spontaneously without a requirement for peritoneal inflammation.9 Here, we describe the continuation of this line of investigation by demonstrating that IL-6 and Myc synergize to create an accelerated mouse model of human PCN.

Despite the early recognition of the importance of IL-6 for PCM,31 the steady progress in our knowledge of IL-6 in the development of normal and malignant plasma cells32 and considerable efforts by the pharmaceutical industry to develop antibody- and small molecule–based therapies for targeting IL-6 in myeloma,33 the promise of IL-6 as a therapeutic target has not yet been translated into appreciable clinical benefits for patients with myeloma. The reasons for this shortcoming include first the disappointing result of clinical trials using an IL-6–targeted mAb,34 which has created lingering pessimism to revisit this approach. Second, newly available, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs, such as bortezomib, thalidomide, and lenalidomide, which are active in patients with PCM who have both relapsed/refractory35 and newly diagnosed disease,36 have raised the bar, making it more difficult for novel IL-6–targeted approaches to demonstrate additional benefit for patients with myeloma. Indeed, it has been argued that any future attempt to include the targeting of IL-6 in new therapeutic regimens for PCM must include the new drugs listed here to gain approval.1 Third, there are considerable gaps in our knowledge concerning the biology of IL-6 in myeloma. For example, the relative contributions of autocrine versus paracrine sources of IL-6 to myeloma development and refractoriness to therapy are not known (supplemental Figure 4A). Likewise, the role that IL-6 trans-signaling37 might play in myeloma is yet to be explored. IL-6 trans-signaling occurs when IL-6 binds to soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R, a truncated form [gp55] of the membrane-bound receptor [gp80]) and then associates with membrane-bound gp130 to initiate JAK/STAT3 signaling (eg, on myeloma cells that may have lost gp80 during tumor progression). We contend that a robust in vivo model of IL-6–dependent PCN, such as strain C.IL6/iMyc, may make it possible to accommodate the increased complexity of preclinical testing of new IL-6 therapies in ways not readily achieved in studies of human myeloma xenografts in immunodeficient mice. C.IL6/iMyc mice may also be useful for addressing the outstanding biologic questions mentioned here.

Considering that our C.IL6/iMyc mouse model of PCT relies on human IL-6 to drive tumor development, the strain may be particularly suitable for validating emerging combination therapies for human PCM that include an anti–IL-6 component. For example, in C.IL6/iMyc mice, bortezomib could readily be combined with the chimeric IL-6–specific antibody CNTO 32838 to recapitulate the “CNTO 328 + Velcade arm” of the ongoing phase 2 myeloma trial. Similarly, strain C.IL6/iMyc may facilitate the preclinical evaluation of Sant 7, a “super” antagonist of IL-639 that exhibits antimyeloma activity in vitro and synergizes with dexamethasone in a transplantation-based severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mouse model of human PCM,40 but has not been tested yet in plasma cell tumors developing de novo in immunocompetent hosts. There is a flurry of new compounds that target IL-6 signaling that are ready to enter the clinical trial arena. These include antibodies to IL-6 and IL-6R,41 small-molecule IL-6R antagonists,42 gp130-targeting peptides,43 and small compounds that target signaling events downstream of the fully assembled, functional IL-6R. Additional therapeutic opportunities are provided by compounds that inhibit pathways that can activate IL-6 signaling indirectly, including NF-κB,44 Hsp90,45 and PI3K/mTOR inhibitors,46 or that activate pathways that can inhibit IL-6 signaling indirectly, as described for PPARγ inhibitors.47 Validating all these agents in a timely and cost-effective manner with patients with myeloma in clinical trials is a daunting proposition, yet it may be accomplished relatively easily using C.IL6/iMyc mice (supplemental Figure 5).

Another emerging treatment strategy for PCM that may be further refined and validated in the C.IL6/iMyc model is targeting paracrine production of IL-6 in the tumor microenvironment. It has been recently shown that a stable, chronic disease state can be induced in patients with smoldering or indolent myeloma by inhibiting IL-1β–dependent IL-6 production in bone marrow stroma (BMS) cells.48 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that high levels of IL-6 produced by BMS cells can stimulate myeloma cells to produce VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and FGF (fibroblast growth factor). These growth factors can, in turn, stimulate IL-6 production by BMS, thereby establishing a classic feed-forward cytokine amplification loop in the tumor microenvironment (reviewed in Meads et al49 ). BMS cells harvested from patients with newly diagnosed PCM before chemotherapy express IL-6 at much higher levels than BMS from healthy donors. Moreover, levels of IL-6 in bone marrow specimens from patients with PCM correlate with stages of clinical disease.49 These findings have led to attempts to block IL-6 production in BMS cells by using inhibitors of FGF/VEGF kinases or histone deacetylase.49 However, the experimental systems available to evaluate these attempts are compromised by their inability to distinguish paracrine from autocrine sources of IL-6. Adoptive transfer of IL6/iMyc–induced PCT (or PCT precursors?) to IL-6–deficient C mice that cannot produce IL-650 or C.IL-6 TG mice with enhanced levels of IL-6 would create a model system in which plasma cell neoplasia can be treated in the absence or constitutive presence of paracrine IL-6 in the tumor microenvironment, respectively (supplemental Figure 4B).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Michael Potter, NCI, NIH, for providing C.IL-6 mice; the staff of our mouse colony, particularly Ling Hu and James Hynes, for excellent technical assistance; and the staff of The Jackson Laboratory strain donation program, particularly Christa Starling and Steve Rockwood, for outstanding assistance.

This work was carried out to fulfill in part the University of Heidelberg Medical School M.D. thesis requirements.

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Award No. P50CA097274 from the NCI.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: S.R. performed research, collected and analyzed data, and assisted in writing the paper; V.T.N. evaluated histologic specimens and assisted in writing the paper; D.-M.S. and W.D. performed research and analyzed data; H.C.M. analyzed data, contributed vital insights to data interpretation, and wrote the paper; H.G. analyzed data, contributed vital understanding of human PCN, and wrote the paper; and S.J. designed, organized, and performed research, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current address of S.R. is Department of Neurology, Neurocenter, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.

Correspondence: Siegfried Janz, 500 Newton Rd, 1046 ML, Iowa City, IA 52242; e-mail: siegfried-janz@uiowa.edu.

![Figure 5. Analysis of signal transduction pathways comparing PCT from C.IL6/iMyc and C.IL6 mice. (A) Schematic overview of signaling pathways chosen for Western blot analyses (B-D). (B-D) Lane numbers correspond to normal splenic B cells (lane 1), PCT from C.IL6 mice (lanes 2-5), PCT from C.IL6/iMyc mice (lanes 6-12, with 3 tumors [lanes 6-8] contained on the blot shown to the left and 4 tumors [lanes 9-12] contained on the blot shown to the right), and commercial positive control (lane 13). Loading of equal protein amounts was documented individually for each Western blot by demonstrating comparable levels of β-actin in all lanes; only one example is shown (D bottom). Pathway screening included IL-6/STAT3/Bcl-XL (B), RAS/ERK (C), and MYC/p19/MDM2/p53 (D).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/115/9/10.1182_blood-2009-08-237941/4/m_zh89990949130005.jpeg?Expires=1769081566&Signature=uGEmm87R7Me8MUFJXbEP8GXD0vqUMxREkkESDKP1Zpc9MeD3UETrV4F1Q51dHWYJGru3EWtVaTyOYwJb25XDqlpSTtH40d2eFN2uYuo4AEj~vMdFgy~AJ9KkStUonGZW8GgERkcdhF6V8io-gcDFIeGLkBQkuK1~hBhGybL6U1wemtQOohcrWlbxPw4zjU9XqNv~9h4EmEoS1FtFpvU4t3AJ1KXRcZ4M2TjZHGVLMW0s42hcWggBb9PzERurFG2REEfWtXYFLAEySzs7FjvL1XpTxq~TFR8yEXyi59jXA-oibm012LCWttAvVIl9mhREVbePY65akqCWf5ArhpBtJQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)