In this issue of Blood, Kremer Hovinga and colleagues demonstrate that a lower level of initial plasma ADAMTS13 activity (< 10%) is associated with higher risk of relapse in patients with TTP. Also, patients with a low plasma ADAMTS13 activity and high-titer inhibitor (≥ 2 BU) appear to have lower survival rate. These findings suggest a role for clinical testing of plasma ADAMTS13 activity and inhibitors in care of TTP patients.

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), a potentially fatal syndrome, is characterized by profound thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Some patients may have symptoms and signs of organ dysfunction.1 Hyaline thrombi in small arterioles and capillaries are the hallmark of pathologic findings. The thrombi contain von Willebrand factor (VWF) and platelets but little fibrin. TTP can be categorized into 2 major forms,2 hereditary TTP and acquired TTP. The former, often seen in children, is caused by mutations of the ADAMTS13 gene; the latter, mainly seen in adults, may be idiopathic or nonidiopathic. Idiopathic TTP may result from autoantibodies that inhibit ADAMTS13 function. Nonidiopathic TTP is secondary to other conditions such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, certain drugs, infections, other autoimmune diseases, cancers, and so on. The nonidiopathic TTP may have also been described as hemolytic uremic syndrome in the literature. With few exceptions (ie, after transplantation or believed secondary to chemotherapy), patients with presumptive diagnosis of TTP are offered plasma infusion or exchange therapy. Plasma therapy has reduced the mortality rate to 20% to 30%.3 Among those who survive the initial acute episode, 20% to 50% of patients relapse (defined as the recurrence of clinical and laboratory abnormalities after achievement of a remission for 30 days). However, it remains difficult to predict clinically which patient will survive and/or relapse and which will not.

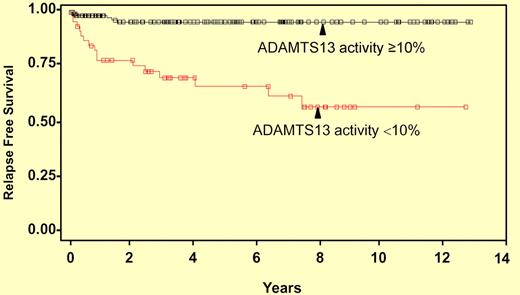

Kaplan-Meier curve of time to first relapse. The y-axis shows the relapse-free survival distribution function, whereas x-axis indicates years of follow-up. Forty-seven surviving patients with ADAMTS13 activity < 10% and 136 patients with ADAMTS13 ≥ 10% were analyzed.

Kaplan-Meier curve of time to first relapse. The y-axis shows the relapse-free survival distribution function, whereas x-axis indicates years of follow-up. Forty-seven surviving patients with ADAMTS13 activity < 10% and 136 patients with ADAMTS13 ≥ 10% were analyzed.

In this issue, Kremer Hovinga et al4 analyze plasma ADAMTS13 activity and inhibitors by FRETS-vWF73 and immunoblotting in a large number of patient samples and correlate the results with clinical information from the Oklahoma TTP Registry. Low levels of plasma ADAMTS13 activity (< 10%) in the initial samples were associated with a higher relapse rate in patients with TTP (see figure). Moreover, the low plasma ADAMTS13 activity (< 10%) and the presence of high-titer inhibitor (≥ 2 BU) predicted worse survival rate among those with idiopathic TTP. These findings suggest a potential role for clinical testing for plasma ADAMTS13 activity and inhibitors in today's comprehensive care for TTP patients. The authors also point out that although much progress has been made in the past decade toward our understanding of the pathogenesis of TTP,1,2 the mortality rate remains high for TTP patients.4 The findings suggest the complexity and clinical heterogeneity of TTP. Further investigation of the underlying pathogenesis and development of better tools for diagnosis and therapy of TTP syndrome are needed.

Various diagnostic tests for ADAMTS13 and inhibitors have been developed, but the FREST-vWF73 assay, using a 73–amino acid peptide derived from the central A2 domain of VWF initially described by Kokame et al,5 has gained popularity. It is relatively simple, rapid, and quantitative. However, the results do not always agree with those obtained by other assays using a multimeric VWF as a substrate. The reported correlation coefficient between the FRETS-vWF73 and the immunoblotting or collagen binding assay is approximately 0.80 or 0.83 for assessing clinical samples.4,6 Therefore, interpretation of the test results requires knowledge of the testing method being used and the patient's clinical information. A combination of 2 or perhaps more different tests may allow identification of more patients with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency.4,6 Although ADAMTS13 testing is not required for initial diagnosis and decision-making for plasma therapy, it may help confirm clinical diagnosis and predict long-term outcomes.4,7,8 Plasma ADAMTS13 activity less than 5% and/or identification of autoantibodies against ADAMTS13 is considered to be highly specific for TTP,9 if a disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is not present. In patients with DIC, acquired severe deficiency of plasma ADAMTS13 was observed.10 These patients rarely have anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies detected in their plasmas. However, it should be noted that normal or mild reduction of plasma ADAMTS13 activity does not rule out TTP, nor should it be used to withhold plasma exchange therapy. Although using a cutoff of 10% of plasma ADAMTS13 activity is more sensitive for predicting relapses as shown in this study,4 such a cutoff may reduce the specificity for diagnosis of TTP.

In summary, the availability of ADAMTS13 testing has helped confirm the clinical diagnosis of TTP and identified patients who have high risk for relapse and/or mortality. Whether a specific therapy should be tailored to an individual patient based on the test result remains to be determined in a future clinical trial.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal