To the editor:

Donahue and colleagues published in Blood a study comparing CD34+ cells mobilized by plerixafor (AMD3100) or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) in macaques.1 Different gene profiling patterns and cell types were produced based on mobilization protocol. The authors postulated that these differences could influence engraftment and toxicity profiles in clinical hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).

Here we provide preclinical data comparing engraftment kinetics and immune reconstitution in our dog leukocyte antigen (DLA)–haploidentical, nonmyeloablative HCT model using stem cells mobilized by either recombinant canine (rc)–G-CSF2 or plerixafor. Prior studies using plerixafor as a single mobilization agent in allogeneic myeloablative HCT resulted in long-term donor reconstitution.3,4 However, no study has been published evaluating its efficacy as a single agent in either nonmyeloablative HCT or across major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–mismatched barriers.

Selection of DLA-haploidentical littermates was based on molecular studies.5,6 All dogs were conditioned identically using a nonmyeloablative preparative regimen consisting of anti-CD44 MAb and 200 cGy total body irradiation, followed by cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil.2 Peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) were collected from donors primed with either plerixafor administered as a single 4-mg/kg subcutaneous (SC) dose 6 hours before leukapheresis (n = 2; hereupon termed “plerixafor dogs”) or rc–G-CSF (n = 9; “G-CSF dogs”) SC from days −5 to 0.2 Graft subsets were phenotyped by flow cytometry.7,8 Chimerism was ascertained by variable number tandem repeat analysis. Absolute lymphocyte and neutrophil counts were followed. In addition, CD4+ and CD8+ reconstitution was evaluated in plerixafor dogs.

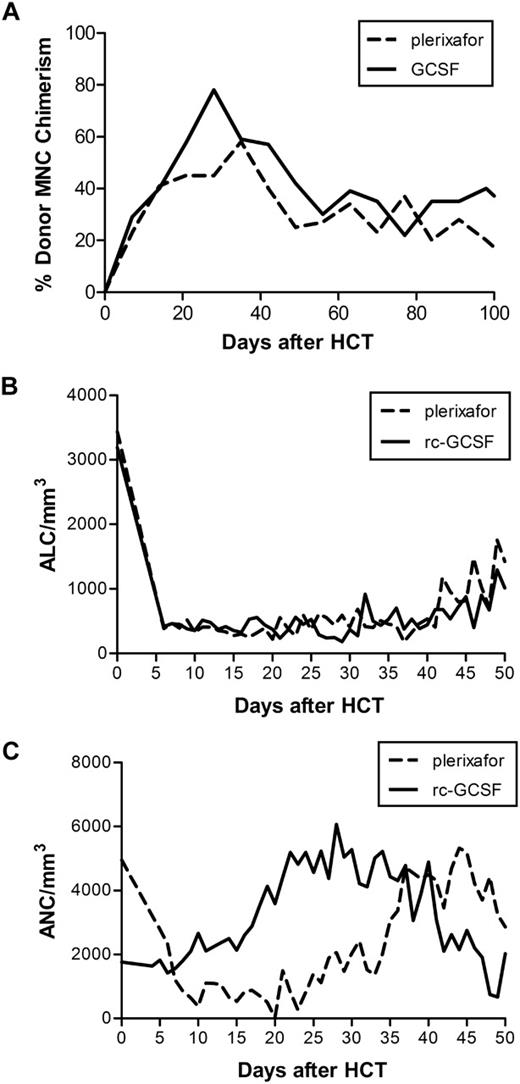

Results showed that in the plerixafor group, median total nucleated, CD34+, CD4+, CD8+, CD3+, and CD14+ cells infused were 16.4 (range, 12.8-19.9) × 108/kg, 4.27 (range, 2.56-5.97) × 106/kg, 2.5 (range, 1.9-3.1) × 108/kg, 0.8 (range, 0.4-1.2) × 108/kg, 4.4 (range, 2.8-5.9) × 108/kg, and 3.9 (range, 3.9) × 108/kg, respectively, while the median doses in rc-G-CSF dogs were 16.1 (range, 9.6-27.2) × 108/kg, 5.30 (range, 2.48-8.87) × 106/kg, 1.6 (range, 1.2-3.0) × 108/kg, 0.4 (range, 0.1-0.6) × 108/kg, 2.3 (range, 1.6-4.0) × 108/kg, and 3.9 (range, 0.6-6.7) × 108/kg, respectively. Both plerixafor dogs (G707 and G484) engrafted without graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). G707 experienced late leukopenia due to sepsis at day +89 after HCT (CD4/μL pre:1632; death:172; CD8/μL pre:308; death:26), whereas G484's CD4 and CD8 counts approached pretransplant levels at rejection at day +147 after HCT (CD4/μL pre:733; death:682; CD8/μL pre:153; death:54). rc-G-CSF dogs engrafted for a median duration of 84 days.2 One of 8 evaluable dogs developed GVHD. Plerixafor-treated dogs had similar absolute lymphocyte counts compared with rc-G-CSF dogs while neutrophil reconstitution appeared delayed (Figure 1).

Plerixafor compared with rc-G-CSF mobilization in study dogs. (A) Median donor mononuclear cell (MNC) chimerism in the first 100 days after HCT in dogs receiving nonmyeloablative conditioning followed by plerixafor-mobilized (dashed line) or rc-G-CSF (solid line) DLA-haploidentical stem cell grafts and posttransplant immunosuppression. (B) Median absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) in dogs receiving plerixafor compared with rc-G-CSF–mobilized PBSC. (C) Median absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in dogs receiving plerixafor compared with rc-G-CSF–mobilized PBSCs.

Plerixafor compared with rc-G-CSF mobilization in study dogs. (A) Median donor mononuclear cell (MNC) chimerism in the first 100 days after HCT in dogs receiving nonmyeloablative conditioning followed by plerixafor-mobilized (dashed line) or rc-G-CSF (solid line) DLA-haploidentical stem cell grafts and posttransplant immunosuppression. (B) Median absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) in dogs receiving plerixafor compared with rc-G-CSF–mobilized PBSC. (C) Median absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in dogs receiving plerixafor compared with rc-G-CSF–mobilized PBSCs.

In conclusion, this small descriptive study is the first to demonstrate that in nonmyeloablative, MHC-haploidentical HCT, plerixafor as a single mobilizing agent facilitated prompt early engraftment without GVHD. Plerixafor-treated dogs had delayed neutrophil reconstitution, perhaps due to up-regulation of myeloid precursors in G-CSF–mobilized products.1 Lymphocyte reconstitution appeared similar perhaps due to longevity of host T cells in nonmyeloablative HCT. Although these findings differ from Burroughs et al,9 this may be a reflection of different immunosuppressive regimens used in myeloablative versus nonmyeloablative canine HCT. In this clinically relevant large animal model where we are testing radiolabeled antibodies10 to induce durable engraftment across DLA-mismatched barriers, an advantage of using plerixafor-mobilized cells would be shorter mobilization time.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: Plerixafor was kindly provided by Genzyme Corporation (formerly Anormed Inc). This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HL36444 and CA15704.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S. Fricker is an employee and G. Bridger is a consultant for Genzyme Corporation, which currently produces plerixafor. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brenda M. Sandmaier, MD, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave N, D1-100, Seattle, WA 98109; e-mail: bsandmai@fhcrc.org.

References

National Institutes of Health