Abstract

Nuclear factors regulate the development of complex tissues by promoting the formation of one cell lineage over another. The cofactor FOG1 interacts with transcription factors GATA1 and GATA2 to control erythroid and megakaryocyte (MK) differentiation. In contrast, FOG1 antagonizes the ability of GATA factors to promote mast cell (MC) development. Normal FOG1 function in late-stage erythroid cells and MK requires interaction with the chromatin remodeling complex NuRD. Here, we report that mice in which the FOG1/NuRD interaction is disrupted (Fogki/ki) produce MK-erythroid progenitors that give rise to significantly fewer and less mature MK and erythroid colonies in vitro while retaining multilineage capacity, capable of generating MCs and other myeloid lineage cells. Gene expression profiling of Fogki/ki MK-erythroid progenitors revealed inappropriate expression of several MC-specific genes. Strikingly, aberrant MC gene expression persisted in mature Fogki/ki MK and erythroid progeny. Using a GATA1-dependent committed erythroid cell line, select MC genes were found to be occupied by NuRD, suggesting a direct mechanism of repression. Together, these observations suggest that a simple heritable silencing mechanism is insufficient to permanently repress MC genes. Instead, the continuous presence of GATA1, FOG1, and NuRD is required to maintain lineage fidelity throughout MK-erythroid ontogeny.

Introduction

Hematopoiesis is a finely tuned developmental process that is controlled by complex networks of nuclear factors. Transcription factors, such as those belonging to the GATA family, ensure the formation of correct proportions of individual cell lineages by favoring the development of one lineage over another and stably maintaining gene expression patterns throughout maturational cell divisions.

The zinc finger DNA-binding proteins GATA1 and GATA2 are essential for the development of the erythroid, megakaryocyte (MK), eosinophil, and mast cell (MC) lineages.1-7 GATA1 activates all known erythroid and MK-specific genes.8,9 In addition, GATA1 functions as a repressor of genes that mark the immature state of erythroid precursor cells, including Gata2 and Kit.10,11 Hypomorphic mutations in the GATA1 gene underlie congenital anemias and thrombocytopenias in human patients.12 Moreover, mutations in GATA1 are associated with megakaryoblastic leukemias in patients with Down syndrome.13 This illustrates the importance of GATA1 for normal erythroid and MK development in vivo.

GATA2 is expressed in hematopoietic stem cells, early progenitor cells, as well as erythroid precursor cells, and controls early stages of hematopoiesis.4,5,14 GATA2 expression is silenced in mature erythroid cells but is continuously expressed in MKs,15 MCs,5 and eosinophils.6,7

The normal functions of GATA1 and GATA2 require binding to the hematopoietic cofactor FOG1, also known as ZFPM1. Point mutations that disrupt FOG1 binding affect normal erythroid and MK development in cellular assays, human patients, and engineered mutant mice.12,16,17 FOG1 is required for the activation and repression of most GATA1-dependent genes.9,17-19 Among the genes directly repressed by GATA1 in a FOG1-dependent manner are Gata2 and Kit.17,18,20,21

Whereas FOG1 synergizes with GATA factors to promote erythroid and MK development, it suppresses the formation of eosinophil and MC lineages via binding to GATA1 and GATA2.22-25 An analogous situation exists in the Drosophila hematopoietic system in which the FOG1 ortholog Ush antagonizes the GATA factor Srp to promote the formation of the crystal cell lineage at the expense of plasmatocytes.26 Thus, FOG1 functions via GATA factors in an evolutionarily conserved pathway to distinctly promote or inhibit the formation of GATA-dependent hematopoietic cell lineages.

Insights into how FOG1 performs activating and repressive functions derived from the identification of associated proteins.20,27,28 Among these is the nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylase complex NuRD, which binds to a small conserved motif at the extreme N-terminus of FOG1 and the cardiac expressed FOG2.20,29 Although the composition of NuRD can vary, the components found in association with FOG1 include 2 histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2, the ATPase Mi-2β, the WD-repeat proteins RBBP7 (RbAp46) and RBBP4 (RbAp48), MTA1/2, p66, and MBD3.20 The ability of NuRD to remodel nucleosomes and deacetylate histones suggests a role in the epigenetic silencing of gene expression.

Conditional mutations of NuRD components have revealed critical requirements for NuRD during several stages of hematopoiesis.30,31 However, because NuRD can associate with diverse nuclear proteins, deletion of individual components produces complex phenotypes, making it difficult to distinguish direct from indirect effects. To directly examine the role of NuRD specifically in the context of the GATA/FOG1 transcription pathway, we used a knock-in strategy to generate mice bearing 3 adjacent point mutations in the N-terminus of FOG1 that disrupt NuRD binding. Mice homozygous for the FOG1 mutations (Fogki/ki) displayed thrombocytopenia and anemia accompanied by splenomegaly, demonstrating that the FOG1/NuRD interaction is essential for normal erythroid and MK maturation.32 Unexpectedly, NuRD was required for both repression and activation of select GATA1/FOG1 target genes.

Here we define the FOG1/NuRD-dependent stages of early hematopoiesis through fluorescence-activated cell sorter phenotyping, colony assays, and gene expression profiling. The erythroid and MK potential of Fogki/ki common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and Fogki/ki MK-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) was significantly impaired, indicating a requirement not only for late-stage maturation but also earlier stages of erythroid and MK differentiation. Importantly, Fogki/ki MEPs retained the ability to differentiate into MCs and other granulocytic lineages when cultured under the appropriate conditions. Fogki/ki MEPs exhibited elevated expression of several MC-specific genes, which persisted in committed erythroid cells and MKs, indicating that NuRD binding by FOG1 is required for repression of MC genes throughout all stages of MK and erythroid development. These results suggest that the GATA/FOG1/NuRD axis not only promotes erythroid and MK maturation but is required for maintaining lineage fidelity by constraining lineage-inappropriate gene expression throughout MK-erythroid development.

Methods

Mice

The generation of homozygous Fogki/ki mice was previously described.32 All mice were maintained on a mixed C57BL/6xSv129 background and analyzed between 5 and 7 weeks of age. Mice were housed in the animal care facility at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Cells

Parental G1E, G1E-ER4, and G1E(V205M)-ER cells were maintained as previously described.33 MKs were differentiated from E14.5 fetal livers by culture in the presence of thrombopoietin (TPO) for 7 days and enriched using a bovine serum albumin gradient. Bone marrow–derived MCs (BMMCs) were derived by culture of bone marrow (BM) in the presence of interleukin-3 (IL-3; 5 ng/mL) and stem cell factor (SCF; 12.5 ng/mL) for more than 5 weeks.34

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Total BM cells were incubated on ice with phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti–murine FcγRII/III. Cells were then exposed to Kit-allophycocyanin–AlexaFluor 750, CD34–AlexaFluor 647, Sca1–fluorescein isothiocyanate, and biotin-labeled antilineage cocktail supplemented with biotin-labeled anti–mouse CD4, anti-CD8a, and anti-CD19. Cells were washed once, stained with streptavidin-PE–Texas Red, and resuspended in a 0.5 μg/mL 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole solution to determine cell viability. Additional information about the antibodies is available in the supplemental data (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Cells were sorted using a BD Biosciences FACSAria cell sorter with the following laser configuration: blue (488 nm), red (647 nm), and UV (355 nm) with DiVa 6.0 software at the University of Pennsylvania Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting core facility. Primary erythroblasts were sorted from BM and spleen with anti–Ter119-PE and anti-CD71 fluorescein isothiocyanate.

Colony assays

For mixed colony assays, sorted progenitor cells were plated at a density of 100 to 1 × 104 cells/mL in methylcellulose medium (M3234; StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 3 U/mL rhEPO (Amgen), 10 ng/mL IL-6 (PeproTech), 10 ng/mL rmIL-3, and 50 ng/mL rmSCF (Invitrogen). For the burst-forming units–erythroid (BFU-E) assay, cells were cultured in 2 U/mL rhEPO and 50 ng/mL rmSCF. BFU-E and myeloid colonies were scored by light microscopy 14 days after plating. Hemoglobinization was measured by staining with benzidine solution. Colony images were acquired with an Axiovert 25 microscope (Carl Zeiss) and Powershot A640 digital camera (Canon). For the colony-forming units (CFU)–MK assay, cells were cultured in MegaCult-C medium in the presence of 20 ng/mL rmIL-6, 10 ng/mL rmIL-3, and 50 ng/mL mTPO as per the manufacturer's instructions (StemCell Technologies). On day 8, CFU-MK colonies were fixed in ice-cold acetone, stained for acetylcholine esterase activity, and counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich). Images were captured using an Axioskop 2 microscope, AxioCam camera, and Axio Vision AC (Release 4.3) software (all from Carl Zeiss).

Histology

A total of 1 × 103 to 2 × 104 cells were spun on to slides and allowed to air-dry briefly before staining with MGG (Sigma-Aldrich) or 0.1% Toluidine blue (in 70% ethanol, pH 2.3).

Retroviral infection

The retroviral vector pGCDNsam containing MSCV-FLAG-mGATA2-ires-green fluorescent protein was kindly provided by A. Iwama (Chiba University). Viral particles were generated by transfection into the PlatE viral packaging line using Lipofectamine 2000. Viral supernatants were collected at 48 hours and used to infect G1E-ER4 cells as described.35 Infected cells were used at 48 hours and were more than 90% green fluorescent protein-positive. GATA2 overexpression was confirmed by Western blotting with anti-GATA2 (H-116; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-FLAG antibodies.

Quantitative RT-PCR

To extract total RNA, freshly isolated CMP, MEP, and granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP; 1-5 × 104 cells) were lysed in Trizol (Invitrogen) in the presence of 2 μg of yeast tRNA. RNA was obtained from 106 cells for remaining cell types. RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript II as per the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) and treated with RNase H before use in real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Primer sequences are listed in supplemental data. All samples were normalized to Actin or Gapdh as indicated.

ChIP assays

For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), 4 × 106 cells per immunoprecipitation were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. For anti-FOG1, anti-MTA2, anti-RbAp46, and anti–Mi-2β ChIPs, cells were additionally cross-linked with ethylene glycol bis(succinimidyl succinate) for 30 minutes before formaldehyde treatment. Nuclei were obtained after incubation of cells in cell lysis buffer (10mM Tris, pH 8.0, 10mM NaCl, 0.2% NP40, 1μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor cocktail, P8340; Sigma-Aldrich), and chromatin was sheared using a Misonix Sonicator 3000. Antibody information is listed in supplemental data. In all experiments, isotype-matched control antibodies were used. Antibodies were used at 10 μg/immunoprecipitation and prebound to Protein A/G beads before overnight incubation with sheared chromatin. Samples were quantified using real-time SYBR Green PCR and analyzed using an Applied Biosystems 7900HT System. Serial dilution of total input chromatin was used to generate a standard curve for each primer and sample set.

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA was isolated from sorted cells using Trizol reagent and amplified using the WT-Ovation Pico System from NuGEN. Sense transcript (ST)-cDNA was generated using the WT-Ovation Exon Module. ST-cDNA was subsequently fragmented and 3′ labeled with biotin using the WT-Ovation Biotin Module V2 (NuGEN). Probes were hybridized to Affymetrix Mouse Gene ST1.0 array chips. All samples were amplified, labeled, hybridized, and scanned at the University of Pennsylvania Microarray Facility according to the manufacturer's protocol. The raw data (.CEL files) were processed by R/Bioconductor (www.bioconductor.org), using the xps package. The probe-level data were normalized and summarized into transcript-level data by the robust multichip analysis method. Processed data were log2-transformed for statistical analysis. Differential expression of transcripts between 2 sample groups was evaluated by the samr package of R/Bioconductor, and genes with a significance analysis of microarray P value of less than .01 and a fold change more than or equal to 1.5 were used for further analysis in Table 1 and supplemental Table 1. Alternatively, Ingenuity Pathway Analyses were performed on whole datasets (Ingenuity Systems). Microarray data were deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE19497.

Genes and fold changes

| Symbol . | Official gene name . | Foldchange . |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulation | ||

| Ms4a2 | Membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 2 (Fcer1b)*† | 14.88 |

| Rgs13 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 13* | 7.03 |

| Alox5ap | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase activating protein* | 6.39 |

| Fcer1a | Fc receptor, IgE, high affinity I, α polypeptide* | 4.51 |

| Scin | Scinderin* | 3.77 |

| Enpp1 | Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1* | 3.39 |

| Cpd | Carboxypeptidase D* | 3.02 |

| Gzmb | Granzyme B* | 2.73 |

| Cd63 | cd63 antigen* | 2.57 |

| Alox5 | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase* | 2.56 |

| Ikzf2 | IKAROS family zinc finger 2 (Helios)* | 2.29 |

| Gata2 | GATA-binding protein 2*† | 2.24 |

| Itpkb | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase B | 2.11 |

| Blnk | B-cell linker | 1.98 |

| Pf4 | Platelet factor 4† | 1.96 |

| Prg2 | Proteoglycan 2, bone marrow* | 1.83 |

| Il12rb2 | Interleukin-12 receptor, β2* | 1.82 |

| Nrarp | Notch-regulated ankyrin repeat protein | 1.78 |

| Klf6 | Kruppel-like factor 6 | 1.77 |

| Mmd | Monocyte to macrophage differentiation-associated | 1.74 |

| Pbx1 | Pre B-cell leukemia transcription factor 1 | 1.72 |

| Sla | Src-like adaptor | 1.65 |

| Malt1 | Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene 1 | 1.64 |

| Lair1 | Leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor 1 | 1.62 |

| Klhl6 | Kelch-like 6 (Drosophila) | 1.61 |

| Ptger3 | Prostaglandin E receptor 3 (subtype EP3)* | 1.60 |

| Ptpn22 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 22 (lymphoid) | 1.59 |

| Irak3 | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 3 | 1.56 |

| Rag1ap1 | Recombination activating gene 1 activating protein 1(Ms4 family)* | 1.55 |

| Fyb | FYN-binding protein* | 1.55 |

| Down-regulation | ||

| Anxa5 | Annexin A5 | −4.68 |

| Grb10 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 10 | −4.20 |

| Prelid2 | PRELI domain containing 2 | −3.90 |

| Cecr2 | Cat eye syndrome chromosome region, candidate 2 homolog (human) | −3.45 |

| Mfhas1 | Malignant fibrous histiocytoma amplified sequence 1 | −3.22 |

| Sh2d4a | SH2 domain containing 4A | −3.15 |

| Cnn3 | Calponin 3, acidic | −2.67 |

| Il2rg | Interleukin-2 receptor, γ chain | −2.53 |

| Hrasls3 | HRAS-like suppressor 3 | −2.37 |

| Thyn1 | Thymocyte nuclear protein 1 | −1.86 |

| Epha7 | Eph receptor A7 | −1.81 |

| Ifitm2 | Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 2 | −1.72 |

| Il10rb | Interleukin-10 receptor, β | −1.71 |

| Ifngr1 | Interferon-γ receptor 1 | −1.66 |

| Hebp1 | Heme-binding protein 1† | −1.62 |

| Il31ra | Interleukin-31 receptor A | −1.56 |

| Crlf3 | Cytokine receptor-like factor 3 | −1.55 |

| Ctla2a | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 2 α | −1.54 |

| Cd82 | CD82 antigen | −1.52 |

| Xk | Kell blood group precursor (McLeod phenotype) homolog | −1.51 |

| Il1r1 | Interleukin-1 receptor, type I | −1.50 |

| Symbol . | Official gene name . | Foldchange . |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulation | ||

| Ms4a2 | Membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 2 (Fcer1b)*† | 14.88 |

| Rgs13 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 13* | 7.03 |

| Alox5ap | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase activating protein* | 6.39 |

| Fcer1a | Fc receptor, IgE, high affinity I, α polypeptide* | 4.51 |

| Scin | Scinderin* | 3.77 |

| Enpp1 | Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1* | 3.39 |

| Cpd | Carboxypeptidase D* | 3.02 |

| Gzmb | Granzyme B* | 2.73 |

| Cd63 | cd63 antigen* | 2.57 |

| Alox5 | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase* | 2.56 |

| Ikzf2 | IKAROS family zinc finger 2 (Helios)* | 2.29 |

| Gata2 | GATA-binding protein 2*† | 2.24 |

| Itpkb | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase B | 2.11 |

| Blnk | B-cell linker | 1.98 |

| Pf4 | Platelet factor 4† | 1.96 |

| Prg2 | Proteoglycan 2, bone marrow* | 1.83 |

| Il12rb2 | Interleukin-12 receptor, β2* | 1.82 |

| Nrarp | Notch-regulated ankyrin repeat protein | 1.78 |

| Klf6 | Kruppel-like factor 6 | 1.77 |

| Mmd | Monocyte to macrophage differentiation-associated | 1.74 |

| Pbx1 | Pre B-cell leukemia transcription factor 1 | 1.72 |

| Sla | Src-like adaptor | 1.65 |

| Malt1 | Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene 1 | 1.64 |

| Lair1 | Leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor 1 | 1.62 |

| Klhl6 | Kelch-like 6 (Drosophila) | 1.61 |

| Ptger3 | Prostaglandin E receptor 3 (subtype EP3)* | 1.60 |

| Ptpn22 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 22 (lymphoid) | 1.59 |

| Irak3 | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 3 | 1.56 |

| Rag1ap1 | Recombination activating gene 1 activating protein 1(Ms4 family)* | 1.55 |

| Fyb | FYN-binding protein* | 1.55 |

| Down-regulation | ||

| Anxa5 | Annexin A5 | −4.68 |

| Grb10 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 10 | −4.20 |

| Prelid2 | PRELI domain containing 2 | −3.90 |

| Cecr2 | Cat eye syndrome chromosome region, candidate 2 homolog (human) | −3.45 |

| Mfhas1 | Malignant fibrous histiocytoma amplified sequence 1 | −3.22 |

| Sh2d4a | SH2 domain containing 4A | −3.15 |

| Cnn3 | Calponin 3, acidic | −2.67 |

| Il2rg | Interleukin-2 receptor, γ chain | −2.53 |

| Hrasls3 | HRAS-like suppressor 3 | −2.37 |

| Thyn1 | Thymocyte nuclear protein 1 | −1.86 |

| Epha7 | Eph receptor A7 | −1.81 |

| Ifitm2 | Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 2 | −1.72 |

| Il10rb | Interleukin-10 receptor, β | −1.71 |

| Ifngr1 | Interferon-γ receptor 1 | −1.66 |

| Hebp1 | Heme-binding protein 1† | −1.62 |

| Il31ra | Interleukin-31 receptor A | −1.56 |

| Crlf3 | Cytokine receptor-like factor 3 | −1.55 |

| Ctla2a | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 2 α | −1.54 |

| Cd82 | CD82 antigen | −1.52 |

| Xk | Kell blood group precursor (McLeod phenotype) homolog | −1.51 |

| Il1r1 | Interleukin-1 receptor, type I | −1.50 |

Microarray analysis of gene expression in wild-type and Fog1 mutant megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors. Representative genes implicated in various stages of hematopoiesis, erythropoiesis, immune system development, or of unknown function are shown as “fold change” relative to wild-type. P < .01; n = 3 experiments.

Genes known to be expressed in mast cells.

Genes known to be regulated by GATA factors.

Results

Expanded hematopoietic progenitor compartments in the BM and spleen of Fogki/ki mice

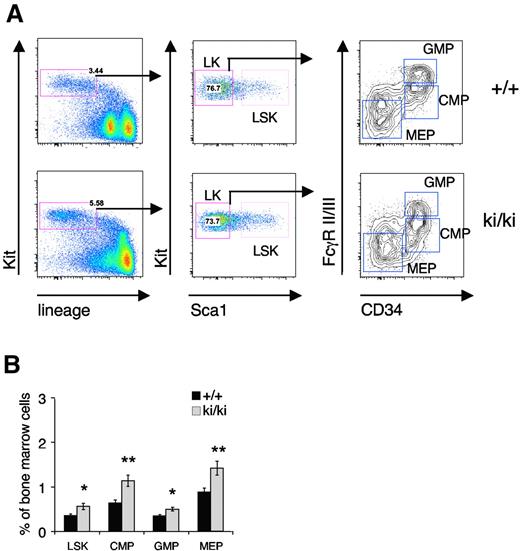

The reduced erythroid and MK potential in the Fogki/ki mice32 could point to defects in the total number of progenitors, reduced proliferation of committed cells, or impaired maturation within the BM compartment of Fogki/ki mice. To differentiate between these possibilities, we began by analyzing the progenitor compartments in the BM from 5- to 7-week-old mice using flow cytometry. Lineage-negative (Lin−) Kit+ progenitor cells were separated into Scal+ hematopoietic progenitors (LSK) and Sca1− myeloid progenitors (LK; Figure 1A). The LK population was further subdivided into the CMP (CD34+FcγRII/IIIlo), MEP (CD34−FcγRII/IIIlo), and GMP (CD34+FcγRII/IIIhi) compartments (Figure 1A).36 A significant increase in the total percentage of LSK cells was observed in the BM of Fogki/ki mice compared with wild-type (WT; Figure 1B). In addition, elevated numbers of CMP, GMP, and MEP were noted in Fogki/ki BM (Figure 1B), consistent with compensatory expansion of stem and progenitor cell compartments. Together with our previous observation of fewer BFU-E and CFU-E, respectively, in total Fogki/ki BM,32 this suggests that Fogki/ki progenitors are impaired after the MEP stage.

Expansion of early progenitors in Fogki/ki BM. Total BM from WT and Fogki/ki mice at 5 to 7 weeks of age. (A) LSK cells from BM were identified via flow cytometry. LK myeloid progenitors were divided into CMP, GMP, and MEP using CD34 and FcγR II/III. (B) The proportions of LSK, CMP, GMP, and MEP were calculated for the BM (n = 10). Errors bars represent SEM. *P < .05, **P < .01 by Student t test.

Expansion of early progenitors in Fogki/ki BM. Total BM from WT and Fogki/ki mice at 5 to 7 weeks of age. (A) LSK cells from BM were identified via flow cytometry. LK myeloid progenitors were divided into CMP, GMP, and MEP using CD34 and FcγR II/III. (B) The proportions of LSK, CMP, GMP, and MEP were calculated for the BM (n = 10). Errors bars represent SEM. *P < .05, **P < .01 by Student t test.

Defective erythropoiesis in Fogki/ki-derived CMP and MEP

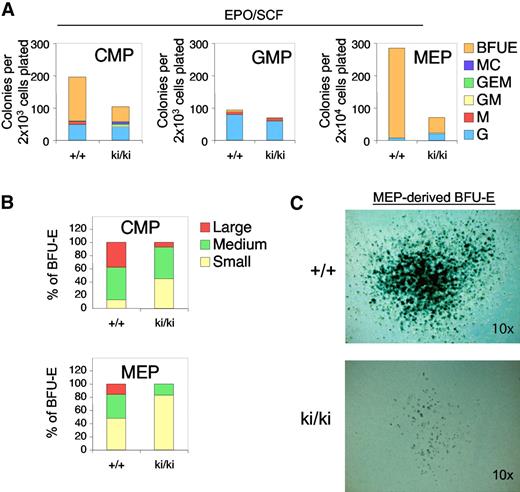

Fogki/ki animals exhibit defects in both erythroid and MK lineages, suggesting the presence of dysfunctional MEP.32 To examine the erythroid and MK potential of Fogki/ki progenitor cells, we prospectively isolated CMP, GMP, and MEP populations and assayed their erythroid potential by plating them in semisolid medium containing EPO and SCF. After 10 days, cultures were stained with the hemoglobin dye benzidine to identify erythroid colonies (BFU-E). Fogki/ki CMP and MEP showed an approximate 3-fold and 6-fold, respectively, decrease in BFU-E activity compared with the WT progenitors (Figure 2A). The GMP compartment from both WT and Fogki/ki mice almost exclusively generated myeloid colonies (Figure 2A middle panel).

Erythroid defects in Fogki/ki CMP and MEP. (A) CMP, GMP, and MEP were cultured in the presence of EPO and SCF and scored at day 14. As control, WT and Fogki/ki GMP produced similar G and M progeny. Results are the average of 3 independent experiments. (B) BFU-E from CMP and MEP were categorized into large (> 50 clusters), medium (16-50 clusters), and small (5-15 clusters); n = 3. (C) Benzidine staining of representative large WT and Fogki/k BFU-E derived from MEP. Original magnification ×10.

Erythroid defects in Fogki/ki CMP and MEP. (A) CMP, GMP, and MEP were cultured in the presence of EPO and SCF and scored at day 14. As control, WT and Fogki/ki GMP produced similar G and M progeny. Results are the average of 3 independent experiments. (B) BFU-E from CMP and MEP were categorized into large (> 50 clusters), medium (16-50 clusters), and small (5-15 clusters); n = 3. (C) Benzidine staining of representative large WT and Fogki/k BFU-E derived from MEP. Original magnification ×10.

To examine the proliferative capacity of erythroid progenitors, we classified WT and Fogki/ki BFU-E colonies as large (> 50 clusters), medium (16-50 clusters), or small (5-15 clusters). Whereas WT CMP and MEP generated a high proportion of medium and large colonies, Fogki/ki progenitors gave rise mainly to small and medium colonies, suggesting a proliferative defect of Fogki/ki cells (Figure 2B). Despite the differences in size and abundance, the presence of fully hemoglobinized cells indicates that erythroid maturation can still take place in the absence of the FOG1/NuRD interaction (Figure 2C). Combined, these data demonstrate an essential role for the FOG1/NuRD interaction in promoting early stages of development of the erythroid lineage from the CMP and MEP compartments.

Defective megakaryopoiesis in Fogki/ki-derived CMP and MEP

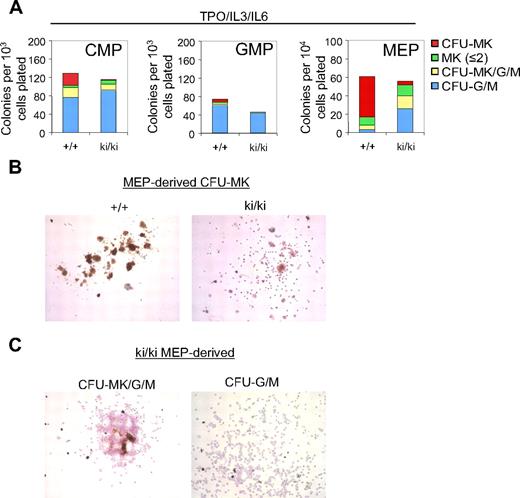

To determine the role of the FOG1/NuRD interaction during megakaryopoiesis, CMP, GMP, and MEP were cultured for 8 days in the presence of TPO, IL-3, and IL-6. MK colony forming units (CFU-MK) were defined as acetylcholine esterase–positive cells (AchE+) with more than or equal to 3 MKs per colony. Notably, whereas approximately 20% of the WT CMP-derived colonies gave rise strictly to CFU-MK, only 2% of Fogki/ki CMP-derived colonies produced mature CFU-MK (Figure 3A left panel). The number of single MK or “colonies” with only 2 MK (MK ≤ 2) was essentially unchanged (Figure 3A left panel). Additional colonies tentatively classified as “mixed” CFU-MK/G/M that in addition to MK contained granulocytic cells (G) and macrophages (M) were also reduced by 40% in Fogki/ki CMP (Figure 3A). In turn, the percentage of Fogki/ki colonies containing either G or M (CFU-G/M) was modestly elevated (80% vs 59% of total colonies; Figure 3A). Finally, Fogki/ki GMP produced slightly fewer CFU-G/M than WT and lacked whatever little MK potential that was detected in WT GMP (Figure 3A middle panel). Together, these results indicate that NuRD binding by FOG1 is required for the generation and expansion of MK progenitors from CMP.

Defective megakaryopoiesis in Fogki/ki CMP and MEP. (A) CMP, GMP, and MEP were cultured with TPO, IL-3, and IL-6 and scored at day 8. CFU-MKs were identified as AchE+ colonies with 3 or more MKs per colony. Other cells were identified by counterstain with Harris hematoxylin. Bars represent numbers of colonies per plated progenitors (n = 3). (B) Representative CFU-MKs derived from WT and Fogki/ki MEP. (C) Representative CFU-MK/G/M (left) and CFU-G/M (right) from Fogki/ki MEP.

Defective megakaryopoiesis in Fogki/ki CMP and MEP. (A) CMP, GMP, and MEP were cultured with TPO, IL-3, and IL-6 and scored at day 8. CFU-MKs were identified as AchE+ colonies with 3 or more MKs per colony. Other cells were identified by counterstain with Harris hematoxylin. Bars represent numbers of colonies per plated progenitors (n = 3). (B) Representative CFU-MKs derived from WT and Fogki/ki MEP. (C) Representative CFU-MK/G/M (left) and CFU-G/M (right) from Fogki/ki MEP.

When grown under conditions favoring MK growth, WT MEP gave rise predominantly to CFU-MK with relatively few colonies with 2 MK or less, CFU-MK/G/M, and CFU-G/M, consistent with published observations.36 By comparison, Fogki/ki MEP gave rise to markedly fewer CFU-MK (Figure 3A right panel). Representative CFU-MK colonies derived from WT and Fogki/ki MEP are shown in Figure 3B. Typically, Fogki/ki CFU-MK exhibited weak staining for AchE, and cells were smaller in size, maturity, and nuclear content (Figure 3B). However, remarkably, Fogki/ki MEP produced elevated numbers of CFU-MK/G/M (∼ 9-fold) and CFU-G/M (∼ 3-fold), suggesting increased myeloid potential (representative Fogki/ki and WT colonies are shown in Figure 3C and supplemental Figure 1, respectively). It should be noted that, despite the severe thrombocytopenia in Fogki/ki mice, the number of mature MK in Fogki/ki BM is essentially normal,32 suggesting the presence in vivo of compensatory mechanisms. In concert, these results demonstrate that disruption of NuRD binding by FOG1 impairs MK expansion and maturation from both CMP and MEP. Importantly, mutant progenitors exhibit increased myeloid potential, suggesting that NuRD is essential for the role of FOG1 during the stable commitment of MEP to the MK lineage.

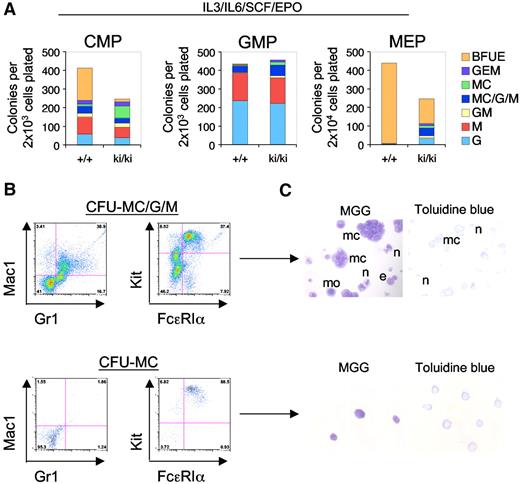

Multilineage myeloid potential of Fogki/ki MEP

FOG1 antagonizes the development of MCs in a manner dependent on GATA1 and GATA2.22,25 We therefore asked whether this function requires NuRD. To evaluate the lineage potential of WT and Fogki/ki MEP, CMP, and GMP, sorted populations were cultured under conditions that are permissive for the development of erythroid and myeloid lineages (IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and EPO). After 14 days of culture, colonies were classified as BFU-E, CFU-G, CFU-M, CFU-MC, or mixtures of these based on morphology. As expected, nearly all (∼ 99%) of the WT MEP-derived colonies were BFU-E. In contrast, Fogki/ki MEP produced only 30% the number of BFU-E colonies compared with WT (Figure 4A). Moreover, 47% of Fogki/ki MEP-derived colonies were nonerythroid of which 52% had the appearance of either pure (CFU-MC) or mixed (CFU-MC/G/M) MC-containing colonies, whereas the remainder belonged to the G/M lineage (Figure 4A).

Myeloid potential of Fogki/ki MEP. (A) CMP, GMP, and MEP were cultured in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and EPO and scored at day 14 (n = 3). (B) Flow cytometric analyses of individual colonies with antibodies against Gr1 (granulocytes), Mac1 (macrophages), and Kit/FcϵR1α (MC). (C) MGG and Toluidine blue stains of representative MC containing colonies from CFU-MC/G/M and CFU-MC. MCs (mc), monocytes (mo), neutrophils (n), and eosinophils (e). Original magnification ×40.

Myeloid potential of Fogki/ki MEP. (A) CMP, GMP, and MEP were cultured in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, SCF, and EPO and scored at day 14 (n = 3). (B) Flow cytometric analyses of individual colonies with antibodies against Gr1 (granulocytes), Mac1 (macrophages), and Kit/FcϵR1α (MC). (C) MGG and Toluidine blue stains of representative MC containing colonies from CFU-MC/G/M and CFU-MC. MCs (mc), monocytes (mo), neutrophils (n), and eosinophils (e). Original magnification ×40.

WT CMP gave rise to an approximately equal proportion of erythroid and nonerythroid colonies (Figure 4A).36 However, Fogki/ki CMP generated only 8.6% the number of BFU-E compared with WT CMP while producing predominantly nonerythroid colonies. Moreover, Fogki/ki CMP generated approximately 6-fold more CFU-MC compared with WT, indicating that NuRD is required for the ability of FOG1 to limit MC production in the CMP as well. Although generally, GMP from WT and Fogki/ki BM gave rise to a very similar spectrum of colonies, increased numbers of MC containing colonies were observed in Fogki/ki cultures (16.2% vs 8.8% in WT; Figure 4A middle panel).

To better define the cellular progeny from cultured Fogki/ki MEP, we examined individual colonies by flow cytometry and histology. Representative flow cytometric and histologic analyses of CFU-MC/G/M and CFU-MC are shown (Figure 4B-C). As predicted, CFU-MC contained only MCs as determined by surface expression of Kit and FcϵRIα, and by staining with MGG and Toluidine blue, whereas CFU-MC/G/M colonies in addition to MCs contained macrophage/monocytes (Mac1+) and neutrophils (Gr1+). Together with previous work demonstrating elevated myeloid potential of Gata1null ES cells,37 this suggests that lineage antagonism by GATA1 functions at least in part through the FOG1/NuRD pathway. When combined with the results from MEP cultured under MK conditions (Figure 3A), our observations indicate that Fogki/ki MEP retain a substantial degree of myeloid potential prominently including MCs.

Deregulated gene expression in Fogki/ki MEP

To obtain a broad and unbiased view of the GATA1/FOG1 target genes that require NuRD, we performed a global gene expression analysis focusing on WT and Fogki/ki MEP because the latter retain myeloid potential and thus probably reveal important FOG1/NuRD targets. RNA obtained from 3 independently isolated BM-derived MEP preparations was hybridized to individual gene arrays. Relative intensities were calculated, and samples showing significant cross-hybridization between arrays were discarded. We analyzed 25 668 unique probe sets comparing Fogki/ki and WT MEP. Expression of 137 genes was elevated more than or equal to 1.5-fold, whereas that of 131 genes was reduced more than or equal to 1.5-fold (significance analysis of microarray, P < .01, n = 3 arrays per cell type). Ingenuity analysis supplemented with additional literature searches generated a representative list of up- and down-regulated genes involved in hematopoietic development (Table 1; the nonbiased list of genes ≥ 1.5-fold can be viewed in supplemental Table 1).

Two major findings emerged from these experiments: (1) several transcription factors implicated in hematopoiesis were up-regulated in Fogki/ki MEP, including Gata2, Ikzf2 (Helios), Pbx1, Meis1, and Klf6; and (2) Fogki/ki MEP overexpressed several MC lineage-specific genes (Figure 5, discussed in the next section). Elevated Gata2 expression in Fogki/ki MEP was of particular interest because Gata2 is normally repressed in a FOG1-dependent manner during the transition from progenitor to mature erythroid cells.17,38 Moreover, Gata2 is essential for MC development,5 raising the possibility that excessive GATA2 levels contribute to the increased MC potential of the Fogki/ki MEP. Importantly, the expression of Gata1 and Fog1 was unchanged. These results were verified by quantitative reverse-transcription (RT) PCR (supplemental Figure 2). Moreover, these genes were not significantly altered in Fogki/ki CMP and GMP (supplemental Figure 2). Thus, the mutation in FOG1 does not impair the ability of GATA1 to regulate its own expression or that of FOG1, consistent with normal protein levels of these factors in Fogki/ki MK and erythroid cells.32 The mRNA levels of Scl (also known as Tal1), which is critical for erythroid, MK, and MC development, was also normal.39-41 Thus, NuRD binding by FOG1 is required for the repression of a few select genes.

Increased MC gene expression in Fogki/ki MEP as determined by gene arrays. Genes were grouped according to their expression in stem cell, stem-myeloid, myeloid-MC, erythroid, MK, and lymphoid compartments. Data are shown as fold change (± SEM) from WT and are the average of 3 independent samples analyzed by microarray (6 arrays total). Other indicates relevant hematopoietic transcription factors.

Increased MC gene expression in Fogki/ki MEP as determined by gene arrays. Genes were grouped according to their expression in stem cell, stem-myeloid, myeloid-MC, erythroid, MK, and lymphoid compartments. Data are shown as fold change (± SEM) from WT and are the average of 3 independent samples analyzed by microarray (6 arrays total). Other indicates relevant hematopoietic transcription factors.

Failure to repress MC-specific transcription in Fogki/ki MEP

In light of the multilineage capacity observed in Fogki/ki MEP, we analyzed the expression array dataset by classifying genes according to the cellular lineages in which they are normally expressed. This was done in a manner similar to that previously used for the study of NuRD-dependent genes in hematopoietic stem cells.31 Genes were assigned to stem cells, stem-myeloid, MC-myeloid, erythroid, MK, and lymphoid (Figure 5).

One of the most salient changes we noted was the elevated expression of several genes normally restricted to the MC lineage, including Fcer1a and Fcer1b (also known as Ms4a2) that encode 2 of the 3 chains of the high affinity receptor for IgE. Indeed, Fcer1b is directly regulated by GATA and FOG proteins.23,35,42 Genes whose products are expressed and stored in MC granules, including Cpd, Prg2 (also known as eosinophil major basic protein), Mcpt8, and Gzmb were also up-regulated. These genes can be individually expressed in other granulocytic (eg, Prg2 in eosinophils) and lymphoid lineages (eg, Gzmb in cytotoxic T cells); however, mature MCs are capable of their coexpression. Fogki/ki MEP also overexpressed Enpp1 (Cd203c) and Lamp3 (Cd63), 2 genes encoding cell surface antigens commonly used to identify MCs and basophils. Finally, we noted increased expression of several genes implicated in MC function (eg, Rgs13, Rag1ap1, Fyb, and Scin) and in eicosanoid synthesis (eg, Alox5ap, Alox5, and Ptger3), a pathway responsible for production of preformed mediators commonly stored within MC granules (Table 1; supplemental Table 1). Gene set enrichment analysis43 confirmed the activation of the MC gene expression program in Fogki/ki MEP (not shown).

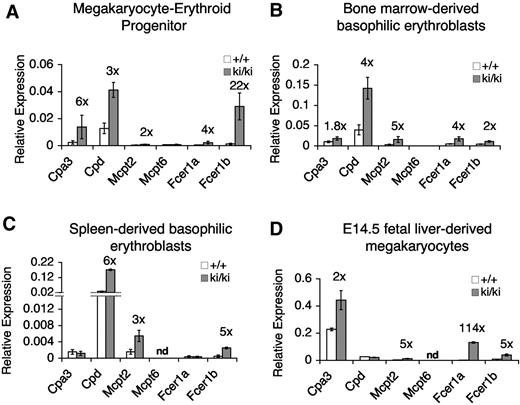

The expression of several MC genes was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 6A). As control, Mcpt6 expression was unchanged, indicating that not all mast cell–specific genes were deregulated. It should be noted that the expression of the deregulated MC genes is still substantially lower than that found in BMMCs (supplemental Figure 3), indicating that failure to repress these genes in MEP is not tantamount to full activation as occurs in mature MCs. Nevertheless, our data indicate that FOG1 and NuRD specifically inhibit the MC lineage in MEP.

Elevated expression of MC-specific genes in Fogki/ki MEP, committed erythroid cells, and MKs. (A-D) mRNA levels of indicated MC genes as determined by quantitative RT-PCR in freshly sorted MEP (A), CD71+Ter119+ basophilic erythroblasts from BM (B) or spleen (C), and cultured fetal liver–derived MK (D). Data were normalized to actin (A) or gapdh (B-D). Numbers above bars indicate the fold change from WT cells. nd indicates not determined. Errors bars represent SEM; n = 3.

Elevated expression of MC-specific genes in Fogki/ki MEP, committed erythroid cells, and MKs. (A-D) mRNA levels of indicated MC genes as determined by quantitative RT-PCR in freshly sorted MEP (A), CD71+Ter119+ basophilic erythroblasts from BM (B) or spleen (C), and cultured fetal liver–derived MK (D). Data were normalized to actin (A) or gapdh (B-D). Numbers above bars indicate the fold change from WT cells. nd indicates not determined. Errors bars represent SEM; n = 3.

FOG1 and NuRD maintain MC gene repression in the mature MK-erythroid compartment

The deregulated expression in primary Fogki/ki MEP of MC genes points to an early role of FOG1 and NuRD in establishing stable lineage-specific gene expression programs. Failure to do so appears to render these cells competent to develop into normal-appearing MCs (Figure 4). Nevertheless, it was important to resolve whether FOG1/NuRD-mediated repression of MC genes occurs only in early progenitors and is subsequently maintained by other factors and/or epigenetic chromatin marks, or whether FOG1 and NuRD are continuously required for lineage appropriate gene expression throughout erythroid and MK maturation. To test this, we measured the expression of MC-specific genes in sorted stage-matched Ter119+CD71+ basophilic erythroblasts from BM and spleens as well as in cultured MK from E14.5 fetal livers. We observed an up-regulation of a similar subset of MC-specific genes in Fogki/ki erythroid cells from BM and spleen (Figure 6B and C, respectively) as well as in Fogki/ki MK (Figure 6D). Therefore, deregulated expression of MC genes is not limited to Fogki/ki MEP. Instead, FOG1 via NuRD assists in both the initiation and maintenance of MC gene repression and maintains lineage fidelity throughout MK-erythroid development.

Repression of MC genes by GATA1 and FOG1

Two mechanisms alone or in combination might account for the deregulated expression of MC genes. First, elevated GATA2 levels might inappropriately activate MC genes in erythroid cells or MKs. Several MC-expressed genes (eg, Cpa3, Fcer1b, Kit, Gata2, Pu.1, and Prg2) are direct targets of GATA factors.22,35,42,44,45 Second, FOG1, which is normally silenced in MCs, might prevent bound GATA1 and GATA2 from activating MC genes in non-MC lineages. To address these questions, we attempted to knock down GATA2 in sorted MEP. However, these cells did not tolerate conditions required for infection with virus expressing anti-Gata2 shRNAs. Moreover, MEP numbers were too small to perform ChIP experiments. Therefore, we used the erythroid cell line G1E because it permits the manipulation of GATA1 and GATA2 levels.

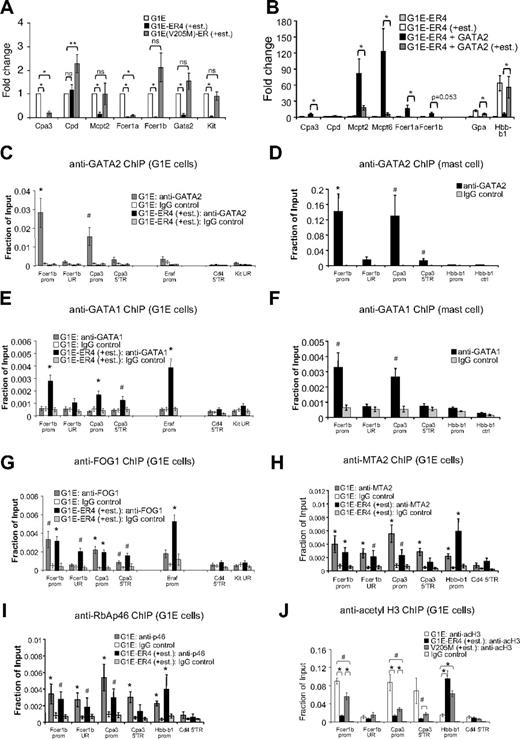

G1E cells are committed erythroid cells lacking GATA1.33 As a result, these cells fail to mature and continue to proliferate presumably because of their high level expression of Kit, Gata2, and Myc. Restoration of GATA1 activity in the context of a stably expressed GATA1-ER (estrogen receptor ligand-binding domain) fusion protein triggers erythroid maturation along with strong induction of β-globin (Hbb-b1) transcription and concomitant loss of Kit, Gata2, and Myc expression.10,17,46 This system faithfully recapitulates normal erythroid maturation and GATA1 function.8 We examined whether the elevated levels of GATA2 found in G1E cells might activate MC-specific genes. Indeed, quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that they express low but detectable amounts of several MC genes, including Cpa3, Mcpt2, Fcer1a, and Fcer1b compared with Fogki/ki MEP and nonhematopoietic 3T3 cells (supplemental Figure 4A). However, mast cell gene expression levels were lower than those found in BMMCs (supplemental Figure 3). We next asked whether MC genes are inhibited by GATA1 during erythroid maturation and whether this requires FOG1. G1E cells expressing GATA1-ER (clone G1E-ER4) were treated with estradiol for 20.5 hours followed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. As expected, Gata2 and Kit expression was reduced (Figure 7A). In addition, we observed repression of the MC-specific genes Cpa3, Mcpt2, Fcer1a, and Fcer1b. To examine the role of FOG1 in this process, we used G1E cells expressing GATA1(V205M)-ER that is impaired for FOG1 binding. GATA1(V205M)-ER failed to repress Gata2 and Kit, consistent with previous observations.17,20 In addition, it failed to repress Fcer1b and Mcpt2, and incompletely repressed Cpa3 and Fcer1a (∼ 19% and 9% expression, respectively, compared with untreated cells; Figure 7A). This is probably a reflection of variable degrees of FOG1 dependence among GATA1 target genes and the fact that the V205M mutation does not completely disrupt FOG1 binding. Failure of GATA1(V205M)-ER to repress Fcer1b and Mcpt2 might be a result of sustained GATA2 expression or an absolute requirement for FOG1. Nevertheless, in concert, these data show that elevated levels of GATA2 are associated with a basal level of MC gene expression in immature erythroid cells and that GATA1 can repress these in a FOG1-dependent manner.

GATA factors and FOG1 regulate MC genes in erythroid cells. (A) mRNA levels of indicated genes as determined by quantitative RT-PCR of G1E cells, and G1E-ER4 and G1E(V205M)-ER cells treated with estradiol for 20.5 hours. Data were normalized to actin and plotted as fold change compared with uninduced G1E cells; n = 3-5. *P < .001; **P < .05; ns indicates not significant. (B) Overexpression of GATA2 in G1E-ER4 cells (G1E-ER4 + GATA2) stimulates MC gene expression, whereas estradiol-activated GATA1-ER (+est.) represses them; n = 6. *P < .05 comparing G1E-ER4 + GATA2 ± estradiol treatment. (C-G) ChIP for GATA2 (C-D), GATA1 (E-F), and FOG1 (G) at FcerIb and Cpa3 in G1E cells (C,E,G) or BMMC (D,F). Control regions included: −7 kb upstream of the FcerIb promoter (UR), an intronic region 3 kb downstream of the Cpa3 promoter (5′TR), the 5′transcribed region of Cd4 (Cd4 5′TR), and a region −224.9 kb upstream of the Kit gene (UR). Positive control, the GATA1-activated Eraf erythroid gene. n = 3-8 independent ChIP experiments per primer set. (H-I) ChIP against MTA2 (H) and RbAp46 (I) in G1E cells and G1E-ER4 (+est.); n = 4-6. The promoter of GATA1-activated Hbb-b1 served as a positive control. *P < .01, #P < .05 by Student t test compared with IgG controls (C-I). (J) ChIP for acetylated histone H3 (acH3) in G1E cells, and G1E-ER4 and G1E(V205M)-ER cells treated with estradiol for 20.5 hours; n = 4-6. *P < .01, #P < .05 by Student t test. Error bars represent SEM.

GATA factors and FOG1 regulate MC genes in erythroid cells. (A) mRNA levels of indicated genes as determined by quantitative RT-PCR of G1E cells, and G1E-ER4 and G1E(V205M)-ER cells treated with estradiol for 20.5 hours. Data were normalized to actin and plotted as fold change compared with uninduced G1E cells; n = 3-5. *P < .001; **P < .05; ns indicates not significant. (B) Overexpression of GATA2 in G1E-ER4 cells (G1E-ER4 + GATA2) stimulates MC gene expression, whereas estradiol-activated GATA1-ER (+est.) represses them; n = 6. *P < .05 comparing G1E-ER4 + GATA2 ± estradiol treatment. (C-G) ChIP for GATA2 (C-D), GATA1 (E-F), and FOG1 (G) at FcerIb and Cpa3 in G1E cells (C,E,G) or BMMC (D,F). Control regions included: −7 kb upstream of the FcerIb promoter (UR), an intronic region 3 kb downstream of the Cpa3 promoter (5′TR), the 5′transcribed region of Cd4 (Cd4 5′TR), and a region −224.9 kb upstream of the Kit gene (UR). Positive control, the GATA1-activated Eraf erythroid gene. n = 3-8 independent ChIP experiments per primer set. (H-I) ChIP against MTA2 (H) and RbAp46 (I) in G1E cells and G1E-ER4 (+est.); n = 4-6. The promoter of GATA1-activated Hbb-b1 served as a positive control. *P < .01, #P < .05 by Student t test compared with IgG controls (C-I). (J) ChIP for acetylated histone H3 (acH3) in G1E cells, and G1E-ER4 and G1E(V205M)-ER cells treated with estradiol for 20.5 hours; n = 4-6. *P < .01, #P < .05 by Student t test. Error bars represent SEM.

Opposing roles for GATA1 and GATA2 in the regulation of MC gene repression in erythroid cells

To examine to what extent, if at all, MC-specific genes are sensitive to elevated GATA2 levels in immature erythroid cells, we infected G1E-ER4 cells with a retroviral vector expressing FLAG-tagged GATA2. Elevation of GATA2 levels by 2- to 5-fold (supplemental Figure 4B) significantly increased the expression of several MC-specific genes, including Cpa3, Cpd, Mcpt2, Mcpt6, Fcer1a, and Fcer1b (Figure 7B). These results are consistent with the capacity of GATA2 to augment MC gene expression in a non-MC context. These effects were gene specific, as GATA2 overexpression did not induce the expression of Gpa or Hbb-b1, 2 genes induced by GATA1.

On treatment with estradiol, GATA1-ER repressed Cpa3, Mcpt2, Mcpt6, and Fcer1a in GATA2-overexpressing cells (Figure 7B). Because GATA1-ER only represses endogenous but not ectopically expressed GATA2 (supplemental Figure 4B), this suggests a direct role for GATA1 in the silencing of MC gene expression.

Direct control of MC genes by GATA1 and GATA2 in erythroid cells

In MCs, Fcer1b and Cpa3 are directly controlled by GATA factors through known GATA elements.35,42 To examine whether in erythroid cells GATA2 activates and GATA1 represses these genes directly, we performed ChIP experiments in parental G1E and G1E-ER4 cells treated with estradiol for 20.5 hours. GATA2 was enriched at the promoters of Fcer1b and Cpa3 in parental G1E cells (Figure 7C) but not at the silent Cd4 gene or a distal upstream region of Kit. The Eraf promoter served as positive control. GATA2 occupancy was not as high as in BMMCs at these genes (Figure 7D) but comparable with that found at the erythroid gene Eraf in G1E cells (Figure 7C). On GATA1-ER induction, GATA2 was reduced at all previously occupied genes, consistent with repression of the Gata2 gene. In addition, GATA1-ER occupied the repressed Fcer1b and Cpa3 promoters at levels similar to those found in BMMCs (Figure 7E-F). FOG1 (Figure 7G) bound the active (via GATA2) and repressed (via GATA1) Fcer1b and Cpa3 genes and thus did not distinguish active from repressive GATA factor complexes. Moreover, the NuRD subunits MTA2, RbAp46, and Mi-2β were detected at the Fcer1b and Cpa3 genes (Figure 7H-I; supplemental Figure 5). As observed previously, NuRD proteins can occupy both active and repressed target genes.32 Therefore, we examined whether the activity of the FOG1/NuRD complex might be differentially controlled between active and repressed target genes. Indeed, repression of the Cpa3 and Fcer1b genes by GATA1 and FOG1 was associated with a dramatic reduction in histone H3 acetylation (Figure 7J). As control, histone acetylation at Hbb-b1 was increased on transcriptional activation. We further confirmed that histone deacetylation was FOG1/NuRD-dependent by measuring histone acetylation at the Cpa3 and Fcer1b genes in G1E(V205M)-ER cells after estradiol treatment (Figure 7J). Combined, these data indicate that GATA1 in conjunction with FOG1 and NuRD directly represses ectopic MC gene expression.

Discussion

Using mice with point mutations in FOG1 that disrupt NuRD binding, we made several observations that extend our previous findings on FOG1 and NuRD during hematopoietic development.32 First, NuRD is required for the normal transition of MEP into MK and erythroid lineages. By using various culture conditions, we further discovered that, unlike their WT counterparts, Fogki/ki MEP display the potential to differentiate into other myeloid lineages, most prominently including MCs. Global gene expression analysis revealed that several genes of the MC lineage but not other lineages are up-regulated in primary uncultured Fogki/ki MEP. Surprisingly, FOG1 and NuRD are required for the repression of MC genes even in committed MK and erythroid progeny. This points toward a continuous requirement for NuRD and FOG1 to actively suppress MC gene expression throughout MK-erythroid ontogeny.

Mechanistic studies suggest 2 ways by which MC gene expression is deregulated in Fogki/ki MK and erythroid cells. One is the up-regulation of GATA2, a direct GATA1/FOG1/NuRD target32 that normally contributes to MC development.5,47,48 In support of this, we found that elevated levels of GATA2 can augment MC gene expression in committed erythroid cells, and GATA2 occupies a subset of MC genes in these cells in vivo. Second, GATA1 via FOG1 and NuRD might directly repress MC genes in non-MC lineages. This possibility is supported by ChIP experiments in erythroid cells demonstrating the presence of GATA1, FOG1, and NuRD at MC gene promoters. Thus, repression of Gata2 and other MC expressed genes requires the direct action of FOG1 and NuRD. This implies that epigenetic silencing mechanisms that are thought to be initiated in early progenitors and sustained by dedicated chromatin modifications are insufficient to permanently silence the MC program throughout hematopoiesis. Conditional disruption of the FOG1/NuRD interaction in mature MK or erythroid cells could be performed in future studies to further test this model.

A role of GATA1 in constraining MC development in MEP was previously reported. Specifically, MEP from mice expressing GATA1 at a fraction of WT mice (Gata1low) were able to generate MCs in addition to MK and erythroid cells.1,49 GATA1 also constrains MC potential of cultured proerythroblasts.37 In addition, the SCL/TAL1 complex, which can associate with GATA1, has been implicated in this pathway. Scl-deficient MEPs maintain MC potential similar to those derived from Fogki/ki and Gata1low mice and, like Fogki/ki MEP, overexpress Gata2.41 Thus, protein complexes associated with GATA1 cooperate to ensure lineage-specific gene expression.

FOG1 restricts MC development in embryonic yolk sacs.22 However, we found no increase in MC production or any other significant changes in the proportion of lineage progeny in Fogki/ki yolk sacs (G.D.G., A.M., and G.A.B., unpublished observations, 2009). This points to a stage-specific requirement for NuRD and suggests that in embryonic cells other FOG1 cofactors, such as CtBP2 or TACC3, might compensate for the loss of NuRD binding.27,28

We also observed that Fogki/ki MEP are capable of forming other myeloid lineages, including eosinophils. This is consistent with previous reports that FOG1 restricts both mast cell and eosinophil development.22-25 However, in contrast to our findings on mast cell genes, we did not detect a significant number of misexpressed genes belonging to other myeloid lineages. It is possible that, in Fogki/ki MEP, myeloid genes are expressed at sub-threshold levels or that they have acquired a poised or open chromatin state that might facilitate their expression on exposure to the appropriate culture conditions. It will be interesting to determine whether in Fogki/ki MEP these genes are marked by histone modifications associated with poised chromatin. Finally, failure to repress myeloid genes is not expected to be sufficient for their high level expression in the absence of myeloid transcriptional activators.

A trivial explanation for the observed mast cell production from Fogki/ki MEP is that cell preparations were contaminated with early progenitors with MC potential. We think that this is unlikely for several reasons. First, almost half of the nonerythroid MEP progeny are MC or mixed MC-containing colonies, which is not easily explained by contamination. Second, flow cytometric analysis of WT and Fogki/ki MEP revealed no differences in the cell surface expression of T1/ST2, a marker for MC progenitors, nor in the expression of CD71 (an early erythroid marker), or CD41 and TPO receptor (an MK marker; data not shown). Third, misexpression of MC genes occurred not only in MEPs but also in committed Fogki/ki erythroid cells and in primary Fogki/ki MKs. Together, this indicates that NuRD is required for specifically constraining mast cell gene programs in the MK-erythroid lineages.

The Fogki/ki mice provided important insights that were not predicted by previous studies. Prior work using overexpressed forms of FOG1 suggested that NuRD is dispensable for inhibiting MC gene expression.22,23 It is possible that high levels of FOG1 expression obscured the NuRD requirement. Similarly, NuRD was thought to be dispensable for FOG1 function during erythroid maturation,50 whereas the work presented here and in a previous report32 indicates otherwise. Although labor-intensive, the knock-in strategy illustrates the great potential to uncover important transcriptional pathways in a physiologic setting.

FOG1 and NuRD are required not only for transcriptional repression but also activation of select GATA1 targets in both MK and erythroid cells.32 Given that FOG1 expression is normally silenced in mast cells, it is expected that activation of GATA1 and GATA2-dependent genes, and therefore maturation, occurs normally in Fogki/ki mast cells. Surprisingly, we find moderate defects in overall number and maturity of mast cells from select tissues in Fogki/ki mice (G.D.G., A.M., and G.A.B., unpublished observation, 2009). Although mast cells in the skin appear to be normal in appearance and number, we observed a moderately reduced percentage of mast cells in the peritoneum of Fog1ki/ki mice (G.D.G., A.M., and G.A.B., unpublished observations, 2009). This could point to a possible role for residual FOG1 levels in early mast cell progenitors. Alternatively, alterations in mast cell development might reflect a different developmental pathway where progeny from Fogki/ki MEP contribute to the mast cell pool. Similarly, in the case of Gata1low mice, MEP have acquired the ability to produce mast cells in vivo.1,49 Further investigation is required to assess the specific role of FOG1 and NuRD in mast cells within different tissues.

In conclusion, this work revealed an important role for the FOG1/NuRD complex in producing normal MK and erythroid cells from MEP and to restrict their differentiation toward MCs. The enduring requirement of this transcription factor complex for the silencing of MC gene expression in committed lineages provides another example illustrating that lineage-specific gene expression patterns are not immutable and might be reprogrammed for the purpose of investigation or therapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hongxin Wang for excellent technical assistance, and laboratory members for insightful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants DK54937 and DK58044, G.A.B.; P01 HL40387, M.P.; 5K01CA115679, W.T.; and training grants T32 HL07439-27 and HL007150-31, G.D.G.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: G.D.G. and A.M. designed and conducted research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; A.B., Y.W., and W.H. conducted research and analyzed data; Z.Z. performed statistical analysis and interpreted microarray gene expression data; M.P. and W.T. designed research and analyzed and interpreted data; and G.A.B. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gerd A. Blobel, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, ARC 316H, 3615 Civic Center Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: blobel@email.chop.edu.

References

Author notes

G.D.G. and A.M. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal