Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is a key cytokine in the effector phase of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after bone marrow transplantation, and TNF inhibitors have shown efficacy in clinical and experimental GVHD. TNF signals through the TNF receptors (TNFR), which also bind soluble lymphotoxin (LTα3), a TNF family member with a previously unexamined role in GVHD pathogenesis. We have used preclinical models to investigate the role of LT in GVHD. We confirm that grafts deficient in LTα have an attenuated capacity to induce GVHD equal to that seen when grafts lack TNF. This is not associated with other defects in cytokine production or T-cell function, suggesting that LTα3 exerts its pathogenic activity directly via TNFR signaling. We confirm that donor-derived LTα is required for graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effects, with equal impairment in leukemic clearance seen in recipients of LTα- and TNF-deficient grafts. Further impairment in tumor clearance was seen using Tnf/Lta−/− donors, suggesting that these molecules play nonredundant roles in GVL. Importantly, donor TNF/LTα were only required for GVL where the recipient leukemia was susceptible to apoptosis via p55 TNFR signaling. These data suggest that antagonists neutralizing both TNF and LTα3 may be effective for treatment of GVHD, particularly if residual leukemia lacks the p55 TNFR.

Introduction

A clear role has been established for tumor necrosis factor (TNF) as an inflammatory mediator of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), in both preclinical and clinical settings.1-3 GVHD is a common and frequently lethal complication of allogeneic bone marrow (BM) transplantation (BMT), and is induced by donor T cells and inflammatory cytokines that cause damage to host epithelial tissues, predominantly the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. GVHD pathogenesis is a 3-stage process.4 Initially, pretransplantation chemotherapy and radiotherapy administration damages host tissue, leading particularly to a loss of gastrointestinal integrity. This in turn allows the translocation of bacterial products (and hence Toll-like receptor ligands) across the gut wall, initiating the release of proinflammatory cytokines (including TNF) from myeloid cells.5 Donor T cells, activated by alloantigen-bearing antigen-presenting cells, become effector cells that provide an additional ongoing source of TNF.2,6

TNF signals through the p55 and p75 TNF receptors (TNFR), which are widely expressed. Signaling of the p55 TNFR results in the direct induction of cellular apoptosis, the hallmark feature of GVHD in target organs.7 Preclinical data generated using donor mice deficient in TNF and/or the TNFRs confirm this as an important ligand-receptor pathway,1,8 predominantly in GVHD of the gastrointestinal tract and skin.9,10 Soluble homotrimers of lymphotoxin α (LTα3) bind the same cell surface receptors as TNF, and because therapeutic agents are available that block TNF alone, or TNF in combination with LTα3, it was important to investigate the importance of soluble LT in both GVHD and graft versus leukemia (GVL). Interestingly, recent experimental data suggest that monoclonal antibodies directed against LTα can preferentially deplete pathogenic T helper 1 and T helper 17 cells in murine models of autoimmune disease,11 providing evidence that specific targeting of cells producing this molecule may be a useful therapeutic in the treatment of other inflammatory conditions.

We have used multiple preclinical models of acute GVHD and GVL to major histocompatibility antigens to study the role of LT molecules in GVHD and GVL. The data generated suggest that LTα3 is an important contributor to GVHD pathogenesis, and that pharmacologic agents that inhibit the activity of this pathway should be considered for study in the treatment of GVHD.

Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6j (H-2b), BALB/c (H-2d), B6D2F1 (H-2b/d), and B6C3F1 (H-2b/k) mice were purchased from the Animal Resources Center. B6.Tnf−/−,12 B6.Lta−/−,13 B6.Ltb−/−,14 and B6.Tnf/Lta−/−12 (all on a C57BL/6j background, H-2b) were supplied by H. Körner (James Cook University). Mice were housed in sterilized microisolator cages and received acidified autoclaved water (pH 2.5) after transplantation.

Bone marrow transplantation

Mice were transplanted, as described previously.15,16 Briefly, on day −1, B6D2F1 mice received 1300 cGy total body irradiation (TBI), B6C3F1 mice 1100 cGy, and BALB/c mice 900 cGy TBI (137 Cs source at 108 cGy/minute), split into 2 doses separated by 3 hours to minimize gastrointestinal toxicity. A total of 5 × 106 BM cells was administered intravenously, with the addition of 0.25 to 2 × 106 purified CD3+ T cells for GVHD test groups. T cell–depleted (TCD) BM was administered to non-GVHD control animals. Animal procedures were undertaken using protocols approved by the institutional animal ethics committee (Queensland Institute of Medical Research). Transplanted mice were monitored daily; those with GVHD clinical scores at least 6 were killed, and the date of death registered as the next day in accordance with institutional animal ethics committee guidelines. In some experiments, recipient mice were given TNFR:Fc (Enbrel; Amgen), or control human immunoglobulin G (IgG; Intragam; Commonwealth Serum Laboratories) at 100 μg/dose, by intraperitoneal injection on alternate days from day 3 to day 30 after transplantation, as previously described.2,17

Assessment of GVHD

The degree of systemic GVHD was assessed by scoring, as previously described (maximum index = 10).18 Briefly, scores were generated based on animal movement, posture, fur ruffling, skin integrity, and weight loss.

Cell preparation

T cells were purified using magnetic bead depletion of non-T–cell splenocytes. Briefly, after red cell lysis, splenocytes were incubated with purified mAb (CD19 [HB305], CD11b [TIB128], anti-B220 [RA36B2], anti-Gr1 [RB6-8C5], and anti-Ly76 [Ter119]) for 20 minutes. Cells were subsequently incubated with goat anti–rat IgG BioMag beads (QIAGEN) for 20 minutes on ice, and antibody-bound cells were removed magnetically. Subsequent CD3+ T-cell purities were more than 80%. BM was prepared by flushing tibiae and femora of donor mice. T-cell depletion of BM was performed by incubating the cells with hybridoma supernatants containing CD4 (RL172.4), CD8 (TIB211), and anti-Thy1.2 (HO-13-4) monoclonal antibodies, followed by incubation with rabbit complement (Cedarlane Laboratories), as previously described.16 Resulting cell suspensions contained less than 1% contamination of viable CD3+ T cells.

Donor T cells (H-2b) for use in in vitro functional assays were sorted based on CD4 or CD8 staining by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), using a MoFlo instrument (DakoCytomation) to more than 95% purity. Splenic dendritic cells were purified using CD11c+ magnetic-activated cell sorting beads and MiniMACS positive selection columns (Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Biologic activity assay

The ability of Enbrel to neutralize the biologic activity of mouse TNF and LTα was confirmed by preincubating 200 μg/mL TNFR:Fc with 2.5 ng/mL recombinant mouse TNF or 0.6 μg/mL recombinant mouse LTα for 30 minutes at 37°C before adding to the murine brain endothelial cell line bEND.319 (ATCC). Control bEND.3 cells were incubated with either culture media alone, cytokines alone, TNFR:Fc alone, or human IgG. After 8-hour culture at 37°C, 5% CO2, cells were assayed for vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression by FACS using rat anti–mouse VCAM-1 and rat anti–mouse ICAM-1 monoclonal antibodies (BioLegend), control rat IgG, and goat anti–rat IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen).

51Cr release assay

Target cells were labeled with 51Cr, as previously described. Target cells (donor type EL4, H-2b; host-type P815, H-2d) were then cultured with donor CD8+ effectors and FACS purified from recipient spleens 14 days after BMT, for 5 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. 51Cr release into supernatants was determined via gamma counter (TopCount microplate scintillation counter; Packard Instrument). Spontaneous release was defined from wells receiving targets only, and total release from wells receiving targets plus 1% Triton X-100. Percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated as follows: percentage of cytotoxicity = (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(total release − spontaneous release) × 100.

Mixed lymphocyte culture

Mixed lymphocyte cultures were set up in triplicate in round-bottom 96-well plates (BD Falcon). T cells were purified from BMT recipient mice at day 14 after transplantation and stimulated with naive B6D2F1 CD11c+ dendritic cells. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 hours before pulsing with tritiated thymidine (3H, 1 μCi/well). Cultures were harvested onto glass fiber filter mats (Wallac) 12 to 16 hours later, and 3H incorporation was determined using a 1205 Betaplate reader (Wallac).

Antibodies

The following mAbs were purchased from BioLegend: fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated CD25 (7D4), CD69 (HI.2F3), and IgG2a isotype control; phycoerythrin-conjugated CD4 (GK1.5), CD8α (53-6.7), TNF (MP6-XT22), TNFRI (55R-286), rat IgG2b, and hamster IgG isotype control; allophycocyanin-conjugated CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), and IgG2b isotype control; biotinylated H-2Dd (34-2-12), TNFRII (TR75-89), rat IgG2a, and hamster IgG isotype control. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated CD3 (KT3), CD4 (GK1.5), and CD8 (53-6.7) were produced in-house. FC receptor blocking was performed before all flow cytometry, and the antibody against FcγRII/III (2.4G2) was also produced in-house.

Cytokine analysis

Serum interferon (IFN)–γ, TNF, interleukin-6, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 were determined using the BD Cytometric Bead Array system (BD Pharmingen). All assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Ex vivo donor splenocytes were stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 (2 μg/mL; 2C11; produced in-house) in the presence of brefeldin A (1/1000 dilution; BioLegend) for 2 hours. Cells were processed for intracellular cytokine staining as per the manufacturer's protocol (BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit; BD Pharmingen).

LTα enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Purified monoclonal antibody against recombinant mouse LTα (clone 168717; R&D Systems) was coated onto 96-well polystyrene plates (Corning Glass) at 2 μg/mL. LTα3 was detected using human TNFR:Fc (Enbrel; Amgen) at 1 mg/mL in 1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline, and quantified using a standard curve generated with recombinant LTα3 (R&D Systems). For detection, sheep anti–human IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Chemicon International) was used at 1:2000 dilution, followed by tetramethylbenzidine substrate (BD Pharmingen). Reactions were stopped with 1M H2SO4 before reading at 490 nm on a tunable microplate reader (VERSAMax; Molecular Devices). The tissue culture supernatants analyzed were generated by stimulating the T-cell population of interest with soluble CD3/CD28 beads (Invitrogen) in a 1:1 (bead:T-cell) ratio for 72 hours before harvesting of tissue culture supernatants.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted and cDNA prepared, followed by real-time, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, as previously described.20,21 PCR was performed on a Corbett Rotorgene 3000 (Corbett Life Sciences). Platinum SYBR Green quantitative PCR Supermix (Invitrogen) was used for Lta and Ltb, and expression of these genes was normalized against expression of the housekeeping gene, HGPRT. Primer sequences were as follows: Lta (5′-CTGCTCACCTTGTTGGGTACCC [forward] and 5′-GACAAAGTAGAGGCCACTGGTG [reverse]) and Ltb (5′-CTCAGAGATCCAATGCTTCC [forward] and 5′-CCAAGCGCCTATGAGGTG [reverse]). Tnf was assessed using a TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems; Accession Mm00443258_m1) and normalized to the β2m housekeeper. For all assays, standard curves were generated to allow a calculation of mRNA transcript number.

Histologic analysis

Formalin-preserved skin and colon were embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic examination. Slides were coded and examined in a blinded fashion by A.D.C. using a semiquantitative scoring system, as previously described.22 An individual score between 0 and 4 was assigned based on extent of cellular apoptosis for each tissue hematoxylin and eosin section. Apoptosis was also assessed by terminal deoxynucleotide transferase deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end label (TUNEL) staining using the ApopTag peroxidase in situ apoptosis detection kit (Chemicon International), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Images of GVHD target tissue were acquired using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus), an Evolution MP 5.0 Camera, and Qcapture software (Qimaging).

Leukemia induction

In both the B6→B6D2F1 and B6→B6C3F1 models, mice received 1100 cGy TBI on day −1. On day 0, B6D2F1 recipients received grafts containing 5 × 106 BM, with 0.5 to 2 × 106 CD3+ T cells and 1 to 2.5 × 104 host-type P815 (DBA/2-derived, H-2Dd, luciferase+) tumor cells. B6C3F1 recipients received 5 × 106 BM plus 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells and 106 32Dp210 (p210) tumor cells (C3H derived, H-2Dk, luciferase+). Cause of death was determined by paralysis (P815 model only), tumor bioluminescence at the time of last imaging, clinical score, and spleen/liver appearance on necropsy.

Bioluminescent imaging

Mice were imaged using the Xenogen, IVIS 100 Bioluminescent Imaging System (Caliper Life Sciences), as described previously.23 Briefly, anesthetized mice were injected subcutaneously with 200 μg firefly luciferin (Caliper Life Sciences), which was allowed to circulate for 5 minutes before image acquisition. Bioluminescent images were captured more than 5 minutes. Animals were imaged weekly for the duration of tumor experiments.

TNF cytotoxicity assay

A total of 105 P815 or p210 tumor cells were plated with recombinant TNF or LTα3 and incubated at 37°C for 5 hours. Apoptosis was assessed using annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (BD Pharmingen), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Survival curves were plotted using Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared by log-rank analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for the statistical analysis of cytokine data, T-cell function, and clinical scores. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean plus or minus SEM.

Results

TNFR:Fc construct protects from GVHD even in the absence of donor-derived TNF

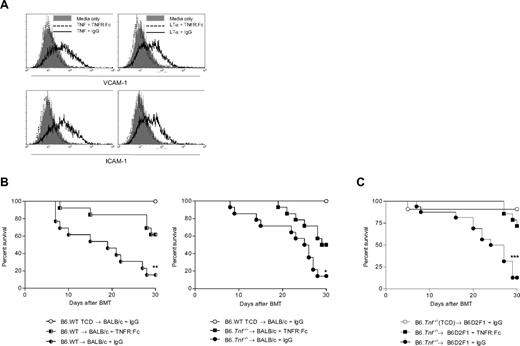

For these studies, we used the human TNFR:Fc construct, which has shown efficacy in the treatment of clinical GVHD,24 and has been used in previous studies to neutralize murine TNF in vivo.2 We first investigated whether this agent was also capable of neutralizing murine LTα3. The murine brain endothelial cell line (bEND.3) is dependent on TNF and LTα3 for the induction of the VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 surface molecules.25 We thus preincubated recombinant mouse TNF or LTα3 with the TNFR:Fc construct or control antibody before stimulation of bEND.3 cells and assessed the relative expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 by flow cytometry. Both LTα3 and TNF induced a similar up-regulation of these integrins (Figure 1A). Importantly, the TNFR:Fc construct completely inhibited the functional activity of both TNF and LTα3, confirming the effective neutralization of both murine molecules. To study whether the TNFR:Fc could still provide protection from GVHD in the absence of donor-derived TNF, we used TNF-deficient mice (B6.Tnf−/−) as donors in the B6→BALB/c transplant model of GVHD against the major histocompatibility complex. We administered either TNFR:Fc construct or control antibody from day 3 to day 30 after transplantation. As shown in Figure 1B, TNFR:Fc treatment provided significant protection from GVHD in the setting of wild-type (WT) and TNF-deficient donors (P = .004 for WT:IgG vs TNFR:Fc; P = .023 for Tnf−/− IgG vs TNFR:Fc). We confirmed the ability of TNFR:Fc to inhibit GVHD in the absence of donor-derived TNF in a second model of GVHD, in which B6.Tnf−/−-deficient grafts were administered to B6D2F1 recipients (Figure 1C).

Administration of TNFR:Fc construct after transplantation attenuates GVHD in the absence of donor-derived TNF. (A) The b.END3 cell line (which is dependent on TNF/LTα3 signaling for the up-regulation of surface VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) was cultured in the presence of recombinant mouse TNF or LTα3 that had been preincubated with either TNFR:Fc or control IgG. Preincubation of recombinant TNF and LTα3 with human TNFR:Fc construct returned expression of these 2 molecules to the basal level seen in untreated cells, whereas incubation with control IgG allowed up-regulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 to occur as expected. VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 surface expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. Plots shown are representative from 2 separate replicate experiments. (B) A total of 5 × 106 BM and 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.WT or B6Tnf−/− donor mice was transplanted into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients (n = 13-14), which were then treated with TNFR:Fc or control IgG on alternate days commencing at day +3 after transplantation and continuing until day 30. TCD bone marrow from B6.WT donors was transplanted into BALB/c recipients (n = 10) as non-GVHD controls (P = .004, WT.B6 donors, TNFR:Fc vs IgG; P = .023, Tnf−/− donors, TNFR:Fc vs IgG). Data combined from 2 replicate experiments. (C) A total of 5 × 106 BM and 2 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.Tnf−/− donor mice was transplanted into lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipients. Recipient mice were treated as described in panel B. Data shown are combined from 2 separate experiments, n = 16, BM plus T groups; n = 7, TCD control group. P = .001, TNFR:Fc treated versus IgG control (T cell–replete groups).

Administration of TNFR:Fc construct after transplantation attenuates GVHD in the absence of donor-derived TNF. (A) The b.END3 cell line (which is dependent on TNF/LTα3 signaling for the up-regulation of surface VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) was cultured in the presence of recombinant mouse TNF or LTα3 that had been preincubated with either TNFR:Fc or control IgG. Preincubation of recombinant TNF and LTα3 with human TNFR:Fc construct returned expression of these 2 molecules to the basal level seen in untreated cells, whereas incubation with control IgG allowed up-regulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 to occur as expected. VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 surface expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. Plots shown are representative from 2 separate replicate experiments. (B) A total of 5 × 106 BM and 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.WT or B6Tnf−/− donor mice was transplanted into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients (n = 13-14), which were then treated with TNFR:Fc or control IgG on alternate days commencing at day +3 after transplantation and continuing until day 30. TCD bone marrow from B6.WT donors was transplanted into BALB/c recipients (n = 10) as non-GVHD controls (P = .004, WT.B6 donors, TNFR:Fc vs IgG; P = .023, Tnf−/− donors, TNFR:Fc vs IgG). Data combined from 2 replicate experiments. (C) A total of 5 × 106 BM and 2 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.Tnf−/− donor mice was transplanted into lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipients. Recipient mice were treated as described in panel B. Data shown are combined from 2 separate experiments, n = 16, BM plus T groups; n = 7, TCD control group. P = .001, TNFR:Fc treated versus IgG control (T cell–replete groups).

The observed protection from GVHD seen with the TNFR:Fc construct may have been due to the neutralization of host-derived TNF (and LTα3), the inhibition of donor-derived LTα3, or both. Given the previously demonstrated importance of donor-derived TNF, and donor cytokine production in general, we hypothesized that donor LTα3 could be performing a similar proinflammatory and proapoptotic role to TNF after transplantation, and as such, investigated the role of LTα in acute GVHD.

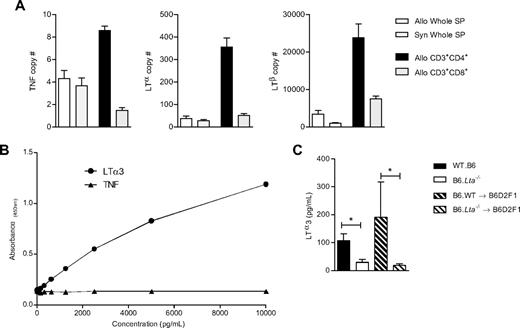

Soluble LTα3 is produced by donor CD4+ T cells after BMT

To identify potential cellular sources of LTα3 after transplantation, we first performed real-time PCR on FACS-purified donor CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations and unfractionated splenocytes from recipients 7 days after BMT. LTα, LTβ, and TNF mRNA levels were highest in donor CD4+ T cells (Figure 2A). Interestingly, transcript levels were similar or moderately reduced in syngeneic versus allogeneic splenocytes, consistent with significant posttranscriptional control of cytokine production (because TNF protein secretion is known to be significantly different in these groups26 ). Because soluble LT protein has not previously been reported in mouse systems, we established an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay system (as described in“Methods”) specific for the LTα3 protein. The standard curves illustrated in Figure 2B demonstrate the specificity of the assay for LTα3, as no cross-reactivity for the TNF molecule was observed. Using this assay, we demonstrate that both naive and posttransplantation CD4+ T cells secrete the soluble protein (Figure 2C) in response to T-cell receptor stimulation.

The production of LTα3 protein by donor T cells can be detected after T-cell receptor ligation. (A) Real-time PCR data showing mRNA expression of TNF, LTα, and LTβ in whole spleen, and FACS-sorted CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ donor T cells taken 7 days after allogeneic BMT. Syngeneic samples represent spleen from B6 recipients of B6 grafts. (B) Standard curve from murine LTα3 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, demonstrating the specificity of the assay for recombinant LTα3. Both TNF and murine LTα3 were serially diluted from a starting concentration of 10 000 pg/mL. (C) CD4+ T cells were isolated from naive B6.WT or B6.Lta−/− mice, or at day 7 after BMT from B6D2F1 recipients of B6.WT or B6.Lta−/− BM plus T-cell grafts. Cells were stimulated with CD3/CD28 beads for 72 hours, and tissue culture supernatants were assessed for LTα3 protein. Data are mean ± SEM, from at least 6 separate experiments. *P < .05.

The production of LTα3 protein by donor T cells can be detected after T-cell receptor ligation. (A) Real-time PCR data showing mRNA expression of TNF, LTα, and LTβ in whole spleen, and FACS-sorted CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ donor T cells taken 7 days after allogeneic BMT. Syngeneic samples represent spleen from B6 recipients of B6 grafts. (B) Standard curve from murine LTα3 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, demonstrating the specificity of the assay for recombinant LTα3. Both TNF and murine LTα3 were serially diluted from a starting concentration of 10 000 pg/mL. (C) CD4+ T cells were isolated from naive B6.WT or B6.Lta−/− mice, or at day 7 after BMT from B6D2F1 recipients of B6.WT or B6.Lta−/− BM plus T-cell grafts. Cells were stimulated with CD3/CD28 beads for 72 hours, and tissue culture supernatants were assessed for LTα3 protein. Data are mean ± SEM, from at least 6 separate experiments. *P < .05.

LT plays a nonredundant role in GVHD pathogenesis

Having demonstrated that donor T cells have the capacity for LTα3 production after transplantation, we next used B6.Tnf−/− and B6.Lta−/− donor mice in the B6→B6D2F1 model of acute GVHD to assess the contribution of these 2 molecules to disease. Importantly, as previously described,14,27 naive donor Tnf−/− and Lta−/− T-cell functional capacity was equivalent in response to alloantigen and mitogen in vitro. Grafts also contained equivalent numbers of naive, memory, and FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (data not shown). In addition, although p55 TNFR signaling is important for regulation of hematopoiesis at the stem cell level,28 recipients of T cell–depleted grafts from donors deficient in TNF, LTα, LTβ, or both TNF and LTα across the various GVHD models did not develop graft failure (data not shown). It has been demonstrated previously that production of TNF by both donor myeloid and T cells after BMT plays an important role in GVHD.6,29 Hence, the grafts used in this study were deficient in the cytokine of interest in both the bone marrow and T-cell compartments.

As shown in Figure 3A, recipients of grafts deficient in either TNF or LTα were equally protected from GVHD (P = .87), compared with control recipients of B6.WT grafts (P < .002). In addition, GVHD clinical scores were consistently reduced in recipients of Tnf−/− or Lta−/− grafts in the first 4 weeks of BMT (data not shown). Importantly, mice deficient in LTα lack both the soluble and the membrane-bound (LTα1β2/LTα2β1) forms of the molecule.12 The membrane-bound heterotrimeric forms signal through the LTβ receptor, expressed on stroma, epithelium, and antigen-presenting cells, and this signaling does not directly induce apoptosis.30 To eliminate the possibility that LTαβ heterotrimers were playing a role in GVHD mortality, we performed transplantations using B6.Ltb−/− donors, which lack only the membrane-bound forms of the molecule. In both the B6→B6D2F1 (Figure 3B) and B6→BALB/c (Figure 3C) models of GVHD, the protective effect seen when grafts lacked LTα was not demonstrated when grafts were deficient only in LTβ. Thus, we confirm that only the LTα3 molecule plays a pathogenic role in mediating acute GVHD. Importantly, this pathogenic role of LTα3 became redundant as the T-cell dose was escalated (Figure 3D), and this was also true for donor-derived TNF (data not shown). We thus observe the most striking effect of LTα3 at low T-cell doses, most likely because other pathogenic inflammatory cytokines (eg, interleukin-1 and IFN-γ) are produced in excess when very high T-cell doses are delivered. Examination of GVHD target organs 21 days after transplantation confirmed a reduction in GVHD severity in both skin and colon (Figure 3E) in the absence of donor LTα. As might be predicted, these are also the classic target organs damaged by TNF during GVHD.9,10 In addition, the degree of apoptosis within these target organs is reduced in the absence of donor LTα (Figure 3F), consistent with this molecule inducing target tissue apoptosis directly via the p55 TNFR, as is the case with TNF itself.8

Soluble LTα3 homotrimer is the important pathogenic lymphotoxin molecule in GVHD. (A) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of lethally irradiated (1300 cGy) B6D2F1 mice transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 2 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.WT, B6.Tnf−/− or B6.Lta−/− donors. Data are combined from 2 separate experiments (n = 16, BM + T groups; n = 6, TCD control group. P = .866, Tnf−/− vs Lta−/−; P < .009, Tnf−/− and Lta−/− vs WT). (B) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipient mice that received BM + T grafts from B6.Lta−/−, B6.Ltb−/− or B6.WT donors. Data shown are combined from 2 separate experiments (n = 18, BM + T groups; n = 10, TCD control group, where TCD marrow was derived from B6 donors that were either B6.WT, B6.Lta−/− or B6.Ltb−/−). P = .018, Lta−/− vs WT; P < .0001 Ltb−/− vs WT. (C) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of lethally irradiated BALB/c recipient mice transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.Ltb−/−, B6.Lta−/− or B6.WT donors. Data shown are combined from 2 separate experiments (n = 12 in BM + T groups; n = 7 in TCD control group where the TCD donor was B6.Ltb−/−. P = .0011 Lta−/− vs WT; P = .212, Ltb−/− vs WT). (D) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of BALB/c recipients of Lta−/− or WT grafts in which the T-cell dose was either 0.25 × 106 CD3+ per graft, or 106 CD3+ per graft. For 0.25 × 106 T cells: n = 10 per BM + T group; P = .0357 Lta−/− vs WT. For 106 T cells: n = 20 per BM + T group; P = .1657 Lta−/− vs WT. (E) Tissues from BALB/c recipient mice transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.Lta−/− (n = 7), B6.WT donors (n = 8), or B6.WT TCD controls (n = 4) were taken 21 days after transplantation. Sections were prepared and scored for histopathology, including apoptosis, as described in “Histologic analysis.” For colon: P = .0016 Lta−/− vs WT; skin: P = .0088 Lta−/− vs WT. Representative photomicrographs (×250) from colon and skin 21 days after BMT. (F) Collated apoptosis scores from colon and skin, as described in “Histologic analysis,” P = .023, Lta−/− vs WT. Photomicrographs (×400) of TUNEL staining on representative colon, as described in “Histologic analysis.” (G) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of lethally irradiated BALB/c recipient mice transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.Tnf−/−, B6.Lta−/−, B6.Tnf/Lta−/−, or B6.WT donors. Data shown are combined from 2 separate experiments (n = 14 in BM + T groups; n = 10 in TCD control group; P ≤ .0007 for Tnf−/−, Lta−/− and Tnf/Lta−/− BM + T groups vs WT).

Soluble LTα3 homotrimer is the important pathogenic lymphotoxin molecule in GVHD. (A) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of lethally irradiated (1300 cGy) B6D2F1 mice transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 2 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.WT, B6.Tnf−/− or B6.Lta−/− donors. Data are combined from 2 separate experiments (n = 16, BM + T groups; n = 6, TCD control group. P = .866, Tnf−/− vs Lta−/−; P < .009, Tnf−/− and Lta−/− vs WT). (B) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipient mice that received BM + T grafts from B6.Lta−/−, B6.Ltb−/− or B6.WT donors. Data shown are combined from 2 separate experiments (n = 18, BM + T groups; n = 10, TCD control group, where TCD marrow was derived from B6 donors that were either B6.WT, B6.Lta−/− or B6.Ltb−/−). P = .018, Lta−/− vs WT; P < .0001 Ltb−/− vs WT. (C) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of lethally irradiated BALB/c recipient mice transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.Ltb−/−, B6.Lta−/− or B6.WT donors. Data shown are combined from 2 separate experiments (n = 12 in BM + T groups; n = 7 in TCD control group where the TCD donor was B6.Ltb−/−. P = .0011 Lta−/− vs WT; P = .212, Ltb−/− vs WT). (D) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of BALB/c recipients of Lta−/− or WT grafts in which the T-cell dose was either 0.25 × 106 CD3+ per graft, or 106 CD3+ per graft. For 0.25 × 106 T cells: n = 10 per BM + T group; P = .0357 Lta−/− vs WT. For 106 T cells: n = 20 per BM + T group; P = .1657 Lta−/− vs WT. (E) Tissues from BALB/c recipient mice transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.Lta−/− (n = 7), B6.WT donors (n = 8), or B6.WT TCD controls (n = 4) were taken 21 days after transplantation. Sections were prepared and scored for histopathology, including apoptosis, as described in “Histologic analysis.” For colon: P = .0016 Lta−/− vs WT; skin: P = .0088 Lta−/− vs WT. Representative photomicrographs (×250) from colon and skin 21 days after BMT. (F) Collated apoptosis scores from colon and skin, as described in “Histologic analysis,” P = .023, Lta−/− vs WT. Photomicrographs (×400) of TUNEL staining on representative colon, as described in “Histologic analysis.” (G) Survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis of lethally irradiated BALB/c recipient mice transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells from B6.Tnf−/−, B6.Lta−/−, B6.Tnf/Lta−/−, or B6.WT donors. Data shown are combined from 2 separate experiments (n = 14 in BM + T groups; n = 10 in TCD control group; P ≤ .0007 for Tnf−/−, Lta−/− and Tnf/Lta−/− BM + T groups vs WT).

Having demonstrated that isolated deficiency of donor-derived TNF and LTα3 decreased GVHD to the same extent (Figure 3A), we next explored disease outcome when donors were deficient in both TNFR-signaling molecules. Transplantations were performed using B6.Tnf/Lta−/− donors, and as shown in Figure 3G, no additional GVHD protection was observed relative to grafts from donors lacking each cytokine in isolation. Interestingly, whereas our original hypothesis after the TNFR:Fc blocking experiments (Figure 1B) was that protection conferred in the absence of donor TNF was due to donor-derived LTα3, these experiments suggest that the protection seen is predominantly due to blockade of host-derived TNF and/or LTα3 by the TNFR:Fc molecule. Nevertheless, these experiments clearly serve to confirm that donor-derived LTα3 is a pathogenic molecule during GVHD.

We next examined inflammatory cytokine levels in the sera of animals 7 days after transplantation (Figure 4A). Surprisingly, these were similar in allograft recipients of T cell–replete grafts, irrespective of whether they were from Lta−/− or WT donors. This suggested that the absence of LTα was not reducing GVHD via downstream effects on other inflammatory cytokines, including TNF.

Absence of LTα does not alter donor T-cell function or inflammatory cytokine generation. (A) B6D2F1 recipients of B6.Lta−/− or B6.WT grafts were bled at day 7, and serum cytokines were analyzed by cytokine bead array, as described in “Cytokine analysis.” (B) Donor T cells were enumerated from the spleens of B6D2F1 recipients 14 days after transplantation. Data shown are absolute number ± SEM per spleen (n ≥ 9). (C) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were assessed by flow cytometry 14 days after transplantation for expression of the activation markers CD25 and CD69 (n = 5-8 per group). (D) Donor splenocytes were cultured for 2 hours with soluble CD3 in the presence of brefeldin A and assessed for production of the inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF by intracellular cytokine staining, as described in “Cytokine analysis” (n = 5-8 per group). (E) Donor CD4+ T cells were sort purified 14 days after transplantation and plated in mixed lymphocyte assays, as described in “Mixed lymphocyte culture.” Proliferation was determined by 3H thymidine uptake. Data are mean ± SEM from triplicate wells and are representative of 3 replicate experiments. (F) CD8+ T cells were sort purified on day 14 after transplantation and plated in chromium release assays with both allogeneic (P815) and syngeneic (EL4) tumor cell targets. Data are mean ± SEM from triplicate wells and are representative of 2 replicate experiments.

Absence of LTα does not alter donor T-cell function or inflammatory cytokine generation. (A) B6D2F1 recipients of B6.Lta−/− or B6.WT grafts were bled at day 7, and serum cytokines were analyzed by cytokine bead array, as described in “Cytokine analysis.” (B) Donor T cells were enumerated from the spleens of B6D2F1 recipients 14 days after transplantation. Data shown are absolute number ± SEM per spleen (n ≥ 9). (C) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were assessed by flow cytometry 14 days after transplantation for expression of the activation markers CD25 and CD69 (n = 5-8 per group). (D) Donor splenocytes were cultured for 2 hours with soluble CD3 in the presence of brefeldin A and assessed for production of the inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF by intracellular cytokine staining, as described in “Cytokine analysis” (n = 5-8 per group). (E) Donor CD4+ T cells were sort purified 14 days after transplantation and plated in mixed lymphocyte assays, as described in “Mixed lymphocyte culture.” Proliferation was determined by 3H thymidine uptake. Data are mean ± SEM from triplicate wells and are representative of 3 replicate experiments. (F) CD8+ T cells were sort purified on day 14 after transplantation and plated in chromium release assays with both allogeneic (P815) and syngeneic (EL4) tumor cell targets. Data are mean ± SEM from triplicate wells and are representative of 2 replicate experiments.

Donor T cells function normally in the absence of LTα

Having established soluble LT as an important inflammatory molecule in GVHD pathogenesis, we examined the effects of this molecule on T-cell expansion and function after transplantation. There was no difference in spleen size, or in CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell numbers when grafts were LTα deficient or WT, nor did donor T cells display any difference in activation status, as measured by CD25 and CD69 expression (Figure 4B-C). In addition, there were no alterations in T-cell responses to ex vivo stimulation as assessed by cytokine generation in response to soluble CD3 (Figure 4D), proliferation in response to alloantigen (Figure 4E), or cytotoxicity against host-type targets (Figure 4F). Thus, deficiency in LTα production from donor cells after transplantation did not appear to influence donor T-cell function.

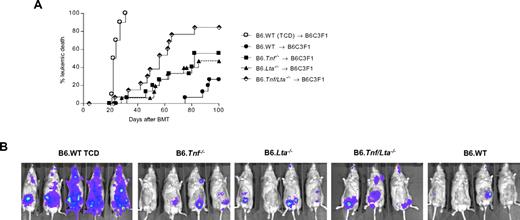

LTα also contributes to the GVL effect after BMT

We next studied the contribution of donor-derived LTα to GVL effects. In the B6→B6D2F1 model of GVHD/GVL, we used luciferase-transfected host-type P815 leukemia and studied leukemia growth after transplantation of B6.WT, B6.Lta−/−, B6.Tnf−/−, or B6.Tnf/Lta−/− grafts (Figure 5A-C). In these studies we observed equivalent leukemia mortality and leukemia burden as assessed by biophotonic imaging (Figure 5D), in the absence of donor LTα or TNF, the absence of both TNFR ligands (ie, B6.Tnf/Lta−/− donor), or when donors were WT. In a second model of GVHD/GVL (B6→B6C3F1), with a different host-type myeloid malignancy (the bcr/abl transfected line, p210), there was clear impairment of GVL effects in the absence of donor-derived LTα, to the same extent as in the absence of donor TNF (P = .82; Figure 6A). Interestingly, the combined absence of both LTα3 and TNF further compromised overall GVL as determined by both survival and biophotonic imaging of leukemia burden (Figure 6B). Thus, GVL effects were decreased in the absence of TNFR ligation in an additive manner, and both TNF and LTα appear to play important and nonredundant roles in GVL.

P815 leukemia is resistant to GVL mediated by donor-derived TNF and LTα3. Leukemia relapse by Kaplan-Meier analysis in lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) B6D2F1 recipients transplanted with grafts from B6.WT or B6.Lta−/− donors, containing 5 × 106 BM cells, and (A) 2 × 106 CD3+ T cells with 2.5 × 104 P815 tumor cells, (P = .60, Lta−/− vs WT; P = .25, Tnf−/− vs WT, T cell–replete groups), or (B) 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells with 5.0 × 104 P815 tumor cells. P = .42, Lta−/− vs WT; P = .98, Tnf−/− vs WT, T cell–replete groups. For panels (A) and (B), data is combined from a minimum of 2 experiments, n ≥ 18, BM + T arms; n = 10, TCD control arm. (C) Lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) B6D2F1 recipients received B6.Tnf/Lta−/− or B6.WT grafts (0.5 × 106 T and 5 × 104 tumor cells). Experiment is 1 of 3 replicate experiments, n = 16, Tnf/Lta−/− group; n = 8, WT BM + T group; n = 5, WT TCD group. P = .65, Tnf/Lta−/− vs WT, T cell–replete groups. (D) Representative biophotonic imaging at day 7 and 14 after BMT confirming leukemia development irrespective of donor-derived LTα, TNF, or both.

P815 leukemia is resistant to GVL mediated by donor-derived TNF and LTα3. Leukemia relapse by Kaplan-Meier analysis in lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) B6D2F1 recipients transplanted with grafts from B6.WT or B6.Lta−/− donors, containing 5 × 106 BM cells, and (A) 2 × 106 CD3+ T cells with 2.5 × 104 P815 tumor cells, (P = .60, Lta−/− vs WT; P = .25, Tnf−/− vs WT, T cell–replete groups), or (B) 0.5 × 106 CD3+ T cells with 5.0 × 104 P815 tumor cells. P = .42, Lta−/− vs WT; P = .98, Tnf−/− vs WT, T cell–replete groups. For panels (A) and (B), data is combined from a minimum of 2 experiments, n ≥ 18, BM + T arms; n = 10, TCD control arm. (C) Lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) B6D2F1 recipients received B6.Tnf/Lta−/− or B6.WT grafts (0.5 × 106 T and 5 × 104 tumor cells). Experiment is 1 of 3 replicate experiments, n = 16, Tnf/Lta−/− group; n = 8, WT BM + T group; n = 5, WT TCD group. P = .65, Tnf/Lta−/− vs WT, T cell–replete groups. (D) Representative biophotonic imaging at day 7 and 14 after BMT confirming leukemia development irrespective of donor-derived LTα, TNF, or both.

p210 leukemia is sensitive to GVL mediated by donor-derived TNF and LTα3. (A) Leukemic relapse by Kaplan-Meier analysis in lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) B6C3F1 recipients transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 0.5 × 106 T cells from B6.WT, B6.Lta−/−, B6.Tnf−/− or B6.Tnf/Lta−/− mice or 5 × 106 B6.WT TCD BM, in conjunction with 1 × 106 p210 tumor cells (H-2Dk, luciferase+). P = .024 Lta−/− vs Tnf/Lta−/−. P = .048, Tnf−/− vs Tnf/Lta−/−. P < .0001 Tnf/Lta−/− vs WT. P = .048 Tnf−/− vs WT, T cell–replete groups. Data are combined from 2 replicate experiments, n = 16 in BM + T groups and n = 10 in TCD control. (B) Representative bioluminescent imaging, taken at day 19 after transplantation.

p210 leukemia is sensitive to GVL mediated by donor-derived TNF and LTα3. (A) Leukemic relapse by Kaplan-Meier analysis in lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) B6C3F1 recipients transplanted with 5 × 106 BM and 0.5 × 106 T cells from B6.WT, B6.Lta−/−, B6.Tnf−/− or B6.Tnf/Lta−/− mice or 5 × 106 B6.WT TCD BM, in conjunction with 1 × 106 p210 tumor cells (H-2Dk, luciferase+). P = .024 Lta−/− vs Tnf/Lta−/−. P = .048, Tnf−/− vs Tnf/Lta−/−. P < .0001 Tnf/Lta−/− vs WT. P = .048 Tnf−/− vs WT, T cell–replete groups. Data are combined from 2 replicate experiments, n = 16 in BM + T groups and n = 10 in TCD control. (B) Representative bioluminescent imaging, taken at day 19 after transplantation.

To investigate the mechanism underlying the different results seen in the 2 leukemia models used, we assessed leukemia cells for expression of the p55 and p75 TNFR. As shown in Figure 7A, the P815 line expresses high levels of the p75 TNFR and negligible levels of the p55 TNFR. Conversely, the p210 line expresses the p55 TNFR exclusively, with negligible levels of p75 TNFR. Importantly, this pattern of TNFR expression was maintained by both cell lines in vivo (Figure 7A). In addition, treatment of leukemia cells with recombinant TNF or LTα3 induced apoptosis, as measured by annexin V, only in the p210 leukemia line, in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 7B-C). We therefore conclude that the P815 leukemia line, which lacks the p55 TNFR, is not susceptible to TNF-mediated apoptosis.

p210 leukemia expresses the p55 TNFR and is directly sensitive to TNFR-mediated apoptosis. (A) In vitro TNFR levels on P815 and p210 tumor cells were measured by flow cytometry, in which gray represents isotype control and black the TNFR staining. Ex vivo B6D2F1 or B6C3F1 mice were transplanted with B6 BM and P815 or P210 leukemia, respectively. At the time point at which mice would normally succumb to leukemia burden, leukemic cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for p55 and p75 TNFR expression. (B) Tumor cell lines were assessed for sensitivity to TNFR-mediated killing by annexin V staining. A total of 105 cells was incubated for 5 hours with recombinant mouse TNF (150 ng/mL), LTα3 (600 ng/mL), or media alone. Data shown are representative of a minimum of 3 replicate experiments. (C) TNFR-mediated killing of the p210 line is dose dependent. Cells were treated, as described in panel B, with escalating doses of TNF.

p210 leukemia expresses the p55 TNFR and is directly sensitive to TNFR-mediated apoptosis. (A) In vitro TNFR levels on P815 and p210 tumor cells were measured by flow cytometry, in which gray represents isotype control and black the TNFR staining. Ex vivo B6D2F1 or B6C3F1 mice were transplanted with B6 BM and P815 or P210 leukemia, respectively. At the time point at which mice would normally succumb to leukemia burden, leukemic cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for p55 and p75 TNFR expression. (B) Tumor cell lines were assessed for sensitivity to TNFR-mediated killing by annexin V staining. A total of 105 cells was incubated for 5 hours with recombinant mouse TNF (150 ng/mL), LTα3 (600 ng/mL), or media alone. Data shown are representative of a minimum of 3 replicate experiments. (C) TNFR-mediated killing of the p210 line is dose dependent. Cells were treated, as described in panel B, with escalating doses of TNF.

Discussion

Previous preclinical studies have demonstrated that soluble TNFR:Fc administration has a protective effect against lethal acute GVHD.2 Using TNF-deficient donors, we have established that this TNFR:Fc-mediated protection occurs via a pathway that is, at least in part, independent of donor-derived TNF. We went on to establish an important role for LT using LTα-deficient donors in both the B6→B6D2F1 and B6→BALB/c models of acute GVHD. We could not observe any downstream defect in the function of donor T cells or inflammatory cytokine generation when the donor graft lacked the capacity to produce LTα, suggesting that LTα3 exerts pathogenic effects during GVHD primarily via its cytopathic capacity. The pattern of (gastrointestinal and cutaneous) target tissue damage induced by LTα and the promotion of apoptosis therein are consistent with this concept and mirror the effects of TNF that use the same receptor.

Soluble LT (formerly referred to as TNF-β) is one of the core members of the TNF superfamily of signaling molecules, and was originally reported in 1968 as a cytolytic factor produced by lymphocytes.31 Like TNF, it is known to promote both apoptosis and proliferation of T cells, along with inflammatory responses.32 There are little data available regarding the presence of LTα3 in various disease states, although it has been detected in the sera of patients with various inflammatory and malignant conditions, including Crohn disease,33 chronic hepatic allograft rejection,34 T-cell leukemia, and osteosarcoma.35 Polymorphisms in the gene encoding LTα have been assessed in GVHD36 ; however, serum levels of the protein have not been examined. Where LTα has been detected in the blood, it was found at lower levels than TNF. LTα3 protein has not previously been measured in the mouse, with previous functional reports relying on PCR analysis of gene expression, or animals genetically deficient in LTα. Functional studies to date have focused on the now well-established role of LTα and LTβ in lymphoid organogenesis.37,38 This is due to the requirement for LTβR ligation on stromal cells during this process (reviewed in Mebius39 ).

Preclinical models have demonstrated that the expression of the p55 TNFR on host tissue is required for the full penetrance of GVHD,8 but of note, removal of p55 TNFR1 signaling on recipient tissue does not eliminate GVHD altogether. Because LTα3 is also generated during GVHD, uses the same signaling pathways as TNF, but signals predominantly via the p55 TNFR,40 it is reasonable to assume that this molecule induces many of the effects previously attributed to TNF in isolation. The additional neutralization of LTα3 by TNFR:Fc molecules (as opposed to anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies, which are specific for TNF and do not cross-react with LTα3) forms part of the basis for the clinical hypothesis that TNFR:Fc treatment may result in different clinical outcomes to the blockade of TNF alone. For example, there are case reports (largely in the field of rheumatoid arthritis) demonstrating efficacy of TNFR:Fc treatment where TNF blockade has failed,41,42 and alternatively, efficacy of the TNF monoclonals over and above that seen with TNFR:Fc treatment. It is hypothesized that the latter may be due to the capacity of TNF monoclonal antibodies to bind to membrane-bound TNF and induce apoptosis in activated, proinflammatory cells.43 To date, no randomized control trials have been performed comparing the efficacy of TNFR:Fc constructs with anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of GVHD, or any other inflammatory conditions.

The equivalent survival in recipients of TNF/LTα-deficient grafts compared with recipients of grafts deficient in either cytokine alone is intriguing and completely unexpected. This suggests 2 possibilities: first, a level of redundancy may exist for these molecules such that the removal of donor-derived TNF and LTα3 in combination does not result in an additive and biologically relevant reduction in signaling through recipient TNFR because of residual host-derived TNF and LTα3. Alternatively, the complete removal of all donor-derived TNFR ligands may improve donor T-cell competency during GVHD late after BMT, and thus, the ability to induce GVHD by alternative (eg, cytotoxic) means. Nevertheless, TNF and LTα3 are clearly capable of causing GVHD pathology in isolation, and the actual balance of these molecules in the posttransplantation milieu is likely to be subject to significant variation within donor-host pairings and conditioning intensity. As such, neutralization of both pathways may represent an important therapeutic option for study in the treatment of clinical GVHD.

Differential signaling of TNF through the 2 TNFRs has been extensively investigated, and it is well established that the p55 TNFR is dominant for cytolytic function, whereas signaling through the p75 TNFR results in the promotion of inflammation.44 The p55 TNFR possesses an intracytoplasmic death domain. Ligation of this receptor recruits cell-signaling proteins that can ultimately lead to the activation of caspase-3 or -8 and apoptosis, as well as the promotion of inflammatory responses. Whereas there is evidence that the p75 TNFR can contribute to cytotoxicity via ligand passing,45 the p75 TNFR does not possess an intracellular death domain. Instead, the intracellular portion of this receptor contains a TNFR-associated factor–interacting protein with ligation leading to translocation of nuclear factor-κB and inflammation (reviewed in Dempsey et al46 ).

Perforin and granzyme are well established as the dominant cytotoxic pathways involved in GVL effects after transplantation.47 Previous investigations into the role of TNF in GVL have been performed using several conditioning regimens (ie, combination TBI and chemotherapy), various TNF-neutralizing regimens, and multiple mouse strain/leukemia combinations.2,6,48-50 Some of these studies report that soluble TNF makes an important contribution to tumor clearance,2,6 whereas others have concluded that TNF is dispensable for maximal antileukemic response.48,50 Thus, results are clearly dependent on a variety of factors. There are 2 elements to the antitumor effects mediated via TNFR signaling, as follows: the direct induction of apoptosis in the target leukemic cell, and the role of TNF in promoting adaptive immune responses. Direct TNFR-mediated apoptosis is likely to be dictated by both the TNFR expression by the tumor and the quantity of TNF and LTα3 produced by the donor cytotoxic T cell. Importantly, we have been able to demonstrate that the P815 leukemia line does not constitutively express the p55 TNFR, and, as may be predicted from its TNFR expression profile, is not directly sensitive to TNF-mediated apoptosis. The differential expression of these receptors on the P815 and p210 leukemia lines is consistent with both their differential sensitivity to TNF-mediated apoptosis in vitro and the observed GVL effects in vivo. Our data therefore suggest that when residual leukemia lacks the p55 TNFR (such as the P815 leukemia), the previously observed defects in GVL after TNF/LT neutralization2,51 are likely to be due to the role of TNF in T-cell priming and costimulation, rather than being directly attributable to its capacity to induce apoptosis in leukemia cells. In contrast, using the TNF-sensitive p210 myeloid leukemia model, we could clearly demonstrate that TNF and LTα3 both have potentially important roles in GVL. This is consistent with previous studies of TNF in the B6→B6C3F1 GVHD/GVL system.6 Importantly, we are now able to show that TNF and the LTα3 homotrimer play equivalent and nonredundant roles in GVL, acting in concert to produce maximal GVL effects.

TNF blockade is now part of standard therapy for steroid-refractory acute GVHD in many institutions.52 Furthermore, a recent trial in which TNF blockade was administered in conjunction with steroid therapy as initial treatment for GVHD demonstrated considerable efficacy, suggesting these agents may be beneficial in first-line therapy of GVHD.24 Although prospective randomized studies are required to confirm this finding and study the effects on GVL more closely, our data suggest that these beneficial effects are at least in part likely to be the result of combined TNF and LTα3 neutralization. These highly promising clinical results, in combination with mechanistic preclinical studies, suggest that combined blockade of TNF and LTα3 may hold considerable therapeutic potential for the treatment of GVHD. However, in situations in which the underlying leukemia expresses the p55 TNFR, it is likely that this therapeutic strategy will also attenuate GVL effects.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We express sincere thanks to Clay Winterford and the staff at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research histology facility for their contribution to this work. We also appreciate Erin Maylin's technical assistance with TUNEL staining.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Queensland Cancer Fund and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. C.R.E. is a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellow; K.P.A.M. is a National Health and Medical Research Council R. D. Wright Fellow; and G.R.H. is a National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellow.

Authorship

Contribution: K.A.M. designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; A.C.B. designed and performed experiments; T.B. performed experimental work and provided useful discussion; R.D.K. performed experimental work and edited the manuscript; N.C.R., V.R., S.D.O., A.L.J.D., E.S.M., A.R.P., Y.A.W., and R.J.R. performed experimental work; L.M.R. performed experiments; H.K. provided critical reagents and useful discussion; C.R.E. provided reagents and useful discussion; A.D.C. analyzed histologic samples; K.P.A.M. designed experiments and contributed to the manuscript; and G.R.H. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Geoffrey R. Hill, Bone Marrow Transplantation Laboratory, Queensland Institute of Medical Research, 300 Herston Rd, Brisbane, QLD 4006, Australia; e-mail: Geoff.Hill@qimr.edu.au.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal