Abstract

Historically, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) beyond 100 days after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) was called chronic GVHD, even if the clinical manifestations were indistinguishable from acute GVHD. In 2005, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored a consensus conference that proposed new criteria for diagnosis and classification of chronic GVHD for clinical trials. According to the consensus criteria, clinical manifestations rather than time after transplantation should be used in clinical trials to distinguish chronic GVHD from late acute GVHD, which includes persistent, recurrent, or late-onset acute GVHD. We evaluated major outcomes according to the presence or absence of NIH criteria for chronic GVHD in a retrospective study of 740 patients diagnosed with historically defined chronic GVHD after allogeneic HCT between 1994 and 2000. The presence or absence of NIH criteria for chronic GVHD showed no statistically significant association with survival, risks of nonrelapse mortality or recurrent malignancy, or duration of systemic treatment. Antecedent late acute GVHD was associated with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality and prolonged treatment among patients with NIH chronic GVHD. Our results support the consensus recommendation that, with appropriate stratification, clinical trials can include patients with late acute GVHD as well as those with NIH chronic GVHD.

Introduction

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains the major cause of late morbidity and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).1 In the past, the presence of any manifestations of GVHD beyond 100 days after HCT was called chronic GVHD, even if the manifestations could not be distinguished from acute GVHD.2,3 In 2005, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored a consensus development conference that proposed new criteria for diagnosis and classification of chronic GVHD for clinical trials.4 Goals of the diagnosis and staging consensus working group were (1) to establish criteria for diagnosis of the disease, emphasizing the distinction between acute and chronic GVHD, (2) to define criteria for scoring the severity of clinical manifestations in affected organs, and (3) to propose categories describing the overall severity of the disease and the indications for treatment.

The current consensus recommends that acute and chronic GVHD should be distinguished by clinical manifestations and not by time after transplantation.4 The consensus conference recognizes 2 main categories of GVHD, each with 2 subcategories. The broad category of acute GVHD includes classic acute GVHD (maculopapular erythematous rash, gastrointestinal symptoms, or cholestatic hepatitis), occurring within 100 days after HCT or donor leukocyte infusion. The broad category of acute GVHD also includes persistent, recurrent or late-onset acute GVHD, occurring more than 100 days after transplantation or donor leukocyte infusion; for brevity, this subcategory is henceforth designated in this manuscript as “late acute” GVHD. The presence of GVHD without diagnostic or distinctive chronic GVHD manifestations defines the broad category of acute GVHD. The broad category of chronic GVHD includes classic chronic GVHD, presenting with manifestations that can be ascribed only to chronic GVHD. The broad category of chronic GVHD also includes an overlap syndrome, which has diagnostic or distinctive chronic GVHD manifestations together with features typical of acute GVHD.

Because the proposed NIH criteria were based on expert opinion, empirical studies are needed to assess their validity. We previously analyzed risk factors associated with nonrelapse mortality and the duration of systemic treatment in a large cohort of patients who had historically defined chronic GVHD after HCT with myeloablative conditioning regimens at our center between 1994 and 2000.5 The current study was designed to address 2 questions. (1) Do late acute GVHD and NIH chronic GVHD show differences in major outcomes, including nonrelapse mortality, recurrent malignancy, overall mortality, and duration of systemic treatment? (2) Do late acute GVHD and NIH chronic GVHD show differences in risk factors associated with nonrelapse mortality and duration of systemic treatment? Differences in outcomes or risk factors would support the validity of the proposed NIH consensus criteria for diagnosis and classification of chronic GVHD. On the other hand, the absence of such differences would raise questions about the clinical significance of the distinction between these 2 syndromes.

Methods

This retrospective study included 740 patients from a previously reported cohort of 751 patients who had HCT after myeloablative conditioning between January 1994 and December 2000 and subsequently required systemic treatment for chronic GVHD.5 Eleven of the 751 previously reported patients were excluded from the current study because consent for use of information for research purposes was revoked (n = 1), systemic treatment was not given for management of chronic GVHD (n = 2), the patient had recurrent malignancy before the onset of chronic GVHD (n = 5), or for other reasons (n = 3). Patients gave written consent allowing the use of medical records for research, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Institutional Review Board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center approved the study.

We retrospectively reviewed medical records and reclassified all patients according to the presence or absence of NIH consensus criteria at the onset of historically defined chronic GVHD requiring systemic treatment.5 Patients with NIH criteria at onset were considered thereafter as having NIH chronic GVHD, either classic chronic GVHD or overlap syndrome. Patients with NIH chronic GVHD were considered as having overlap syndrome if they had liver, gut, or skin manifestations typical of acute GVHD. Patients with manifestations that did not meet NIH criteria were classified as having late acute GVHD at onset, which includes persistent, recurrent, or delayed-onset acute GVHD. Records for these patients were reviewed to determine whether manifestations of GVHD satisfied NIH criteria at any subsequent time. If so, a date of transition from late acute GVHD to NIH chronic GVHD was assigned, and the patient was considered as having NIH chronic GVHD thereafter. An ocular NIH clinical score of 2 or 3 without the Schirmer test was accepted as sufficient to define ocular involvement. Rash was defined as a cutaneous manifestation of acute GVHD unless lichen planus or sclerotic features or other distinctive cutaneous features were noted.

Chronic GVHD was generally treated with prednisone and continued administration of calcineurin inhibitor as previously described.5,6 Patients who had participated in randomized clinical trials comparing cyclosporine versus tacrolimus for prevention of acute GVHD continued administration of the same calcineurin inhibitor after the onset of chronic GVHD. Prednisone was administered initially at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for at least 2 weeks unless patients were already being treated with higher doses of prednisone when chronic GVHD was diagnosed. The dose of prednisone was tapered over 6 weeks as tolerated to 1 mg/kg every other day. Calcineurin inhibitor was administered daily for patients with unrelated donors. For patients with related donors, calcineurin inhibitor was administered either every other day7 or daily, according to current practice.8 Doses of calcineurin inhibitor were adjusted as needed to avoid toxicity. After resolution of chronic GVHD, systemic treatment was gradually withdrawn by tapering first the doses of prednisone and then the doses of calcineurin inhibitor as tolerated.9

The data used in our retrospective studies relied on available medical records from outside medical providers providing the primary care of our patients and on documentation generated by a dedicated long-term follow-up (LTFU) program. This documentation included (1) telephone notes documenting any contact with patients and their physicians, (2) on-site consultation visits with the LTFU clinical service at a departure evaluation between 80 and 100 days after HCT, at one-year LTFU evaluation visit, at chronic GVHD follow-up visits usually at 6-month intervals if possible or, as clinically indicated, (3) correspondence, (4) GVHD forms completed by outside providers, patients, or LTFU medical staff, and (5) LTFU questionnaires sent at 6 months and yearly after transplantation to all patients and their primary care providers.

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed according to information available as of July 2008. We evaluated differences in risks of nonrelapse mortality and recurrent malignancy, overall survival, and discontinued systemic treatment between patients with NIH chronic GVHD compared with patients with late acute GVHD. Cumulative incidence estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) were computed according to methods described previously.10

Factors evaluated for association with outcome included age of the patient at transplantation, pretransplantation disease risk category, time from pretransplantation diagnosis to transplantation, donor/patient gender, donor parity, donor age, donor type (related or unrelated), graft-versus-host mismatching at individual human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci (A, B, C, DRB1, DQB1), number of mismatched HLA loci in the recipient, source of stem cells, year of transplantation, use of tacrolimus for GVHD prophylaxis, grade of acute GVHD, time from transplantation to diagnosis of chronic GVHD, type of onset, individual sites affected by chronic GVHD (skin, eyes, mouth, gastrointestinal tract, liver, lung, other), number of sites affected, dose of prednisone at the onset of chronic GVHD, total serum bilirubin concentration more than 2.0 mg/dL at the onset of chronic GVHD, and platelet count less than 100 000/μL at the onset of chronic GVHD. Factors having a P value less than .1 for association with outcome by univariate testing were added sequentially to a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model using a step-up procedure until the P value for the likelihood ratio test was greater than .05. Death and the onset of recurrent malignancy were competing risks in the analysis of discontinued systemic treatment. The onset of recurrent malignancy was a competing risk in the analysis of nonrelapse mortality. P values are 2-sided and are not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patients, transplantation, and GVHD characteristics

On retrospective review, we found that initial manifestations did not meet NIH consensus criteria for chronic GVHD in 352 (48%) of the 740 patients originally identified as having chronic GVHD. Among the remaining 388 patients with initial manifestations that met NIH criteria, 35 (9%) had classic chronic GVHD with no cutaneous erythema or involvement of the liver or gastrointestinal tract. Demographic and transplantation characteristics for the 352 patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD (acute onset) and the 388 patients who presented with NIH chronic GVHD (chronic onset) were similar (Table 1), except that patients in the acute onset group were somewhat younger (P = .007) and had somewhat higher peak grades of antecedent acute GVHD (P = .005) than those in the chronic onset group. As shown in Table 2, GVHD characteristics at onset were similar in the 2 groups, except that gastrointestinal involvement was more prevalent in the acute onset group (P < .001). By definition, ocular and oral mucosal manifestations were documented at onset only in the chronic onset group. We identified 100 patients who had a transition from late acute GVHD to NIH chronic GVHD: 12 with progressive onset (persistent per NIH criteria4 ), 75 with quiescent onset (recurrent per NIH criteria4 ), and 13 with de novo onset (late per NIH criteria4 ).

Patient and transplantation characteristics according to initial presentation

| Characteristic . | Acute onset (n = 352) . | Chronic onset (n = 388) . |

|---|---|---|

| Patient median age, y (range) | 37.2 (0.8-67.0) | 41.8 (1.4-66.4) |

| Disease at transplantation, no. (%) | ||

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 48 (14) | 67 (17) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 71 (20) | 72 (19) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 146 (41) | 151 (39) |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 52 (15) | 42 (11) |

| Chronic lymphoid leukemia | 4 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma or Hodgkin disease | 10 (3) | 34 (9) |

| Multiple myeloma | 4 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Other* | 17 (5) | 9 (2) |

| Pretransplantation risk category, no. (%)† | ||

| Low | 142 (40) | 143 (37) |

| Intermediate | 150 (43) | 171 (44) |

| High | 60 (17) | 74 (19) |

| Donor median age, y (range) | 40.0 (0.0-81.7) | 39.0 (0.0-70.9) |

| Donor/recipient sex, no. (%) | ||

| Male/male | 122 (35) | 122 (31) |

| Male/female | 73 (21) | 87 (22) |

| Female/male | 90 (26) | 107 (28) |

| Female/female | 67 (19) | 72 (19) |

| Donor type, no. (%) | ||

| HLA-identical related | 152 (43) | 176 (45) |

| HLA-mismatched related | 35 (10) | 24 (6) |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 83 (24) | 101 (26) |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated | 82 (23) | 87 (22) |

| No. of mismatched HLA loci‡ (%) | ||

| 0 | 243 (69) | 282 (73) |

| 1 | 64 (18) | 65 (17) |

| 2 | 42 (12) | 29 (7) |

| More than 2 | 3 (1) | 12 (3) |

| Conditioning regimen, no. (%) | ||

| Cyclophosphamide and TBI | 196 (56) | 215 (55) |

| Busulfan and cyclophosphamide | 114 (32) | 127 (33) |

| Busulfan and TBI | 16 (5) | 26 (7) |

| Other | 26 (7) | 20 (5) |

| Source of stem cells, no. (%) | ||

| Bone marrow | 289 (82) | 302 (78) |

| Mobilized blood | 59 (17) | 85 (22) |

| Cord blood | 4 (1) | 1 (< 1) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, no. (%) | ||

| Cyclosporine plus methotrexate | 297 (84) | 329 (85) |

| Tacrolimus plus methotrexate | 12 (3) | 11 (3) |

| Other | 43 (12) | 48 (12) |

| Year of transplantation, no. (%) | ||

| 1994-1997 | 203 (58) | 217 (56) |

| 1998-2000 | 149 (42) | 171 (44) |

| Prior acute GVHD before day 100, no. (%) | ||

| Grade 0-I | 34 (10) | 69 (18) |

| Grade II | 222 (63) | 229 (59) |

| Grades III-IV | 96 (27) | 90 (23) |

| Characteristic . | Acute onset (n = 352) . | Chronic onset (n = 388) . |

|---|---|---|

| Patient median age, y (range) | 37.2 (0.8-67.0) | 41.8 (1.4-66.4) |

| Disease at transplantation, no. (%) | ||

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 48 (14) | 67 (17) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 71 (20) | 72 (19) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 146 (41) | 151 (39) |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 52 (15) | 42 (11) |

| Chronic lymphoid leukemia | 4 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma or Hodgkin disease | 10 (3) | 34 (9) |

| Multiple myeloma | 4 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Other* | 17 (5) | 9 (2) |

| Pretransplantation risk category, no. (%)† | ||

| Low | 142 (40) | 143 (37) |

| Intermediate | 150 (43) | 171 (44) |

| High | 60 (17) | 74 (19) |

| Donor median age, y (range) | 40.0 (0.0-81.7) | 39.0 (0.0-70.9) |

| Donor/recipient sex, no. (%) | ||

| Male/male | 122 (35) | 122 (31) |

| Male/female | 73 (21) | 87 (22) |

| Female/male | 90 (26) | 107 (28) |

| Female/female | 67 (19) | 72 (19) |

| Donor type, no. (%) | ||

| HLA-identical related | 152 (43) | 176 (45) |

| HLA-mismatched related | 35 (10) | 24 (6) |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 83 (24) | 101 (26) |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated | 82 (23) | 87 (22) |

| No. of mismatched HLA loci‡ (%) | ||

| 0 | 243 (69) | 282 (73) |

| 1 | 64 (18) | 65 (17) |

| 2 | 42 (12) | 29 (7) |

| More than 2 | 3 (1) | 12 (3) |

| Conditioning regimen, no. (%) | ||

| Cyclophosphamide and TBI | 196 (56) | 215 (55) |

| Busulfan and cyclophosphamide | 114 (32) | 127 (33) |

| Busulfan and TBI | 16 (5) | 26 (7) |

| Other | 26 (7) | 20 (5) |

| Source of stem cells, no. (%) | ||

| Bone marrow | 289 (82) | 302 (78) |

| Mobilized blood | 59 (17) | 85 (22) |

| Cord blood | 4 (1) | 1 (< 1) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, no. (%) | ||

| Cyclosporine plus methotrexate | 297 (84) | 329 (85) |

| Tacrolimus plus methotrexate | 12 (3) | 11 (3) |

| Other | 43 (12) | 48 (12) |

| Year of transplantation, no. (%) | ||

| 1994-1997 | 203 (58) | 217 (56) |

| 1998-2000 | 149 (42) | 171 (44) |

| Prior acute GVHD before day 100, no. (%) | ||

| Grade 0-I | 34 (10) | 69 (18) |

| Grade II | 222 (63) | 229 (59) |

| Grades III-IV | 96 (27) | 90 (23) |

Twenty-four patients had diseases other than hematologic malignancies.

The low-risk category included chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase and aplastic anemia. The high-risk category included chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis, acute leukemia or lymphoma in relapse, refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, and myeloma. The intermediate-risk category included all other diseases.

HLA-C and -DQ typing was not available for 3 cord blood donors. HLA-C and -DQ typing was not available for one marrow donor at each locus.

GVHD characteristics

| Characteristic . | Acute onset (n = 352) . | Chronic onset (n = 388) . |

|---|---|---|

| Median time from transplantation to diagnosis, mo (range) | 3.6 (2.4-20.9) | 4.4 (2.2-28.2) |

| Type of onset, no. (%) | ||

| De novo (late*) | 43 (12) | 66 (17) |

| Quiescent (recurrent*) | 265 (75) | 264 (68) |

| Progressive (persistent*) | 44 (13) | 58 (15) |

| Sites involved at onset, no. (%) | ||

| Skin | 190 (54) | 261 (67) |

| Eyes | 0 | 92 (24) |

| Mouth | 0 | 333 (86) |

| Liver | 106 (30) | 136 (35) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 218 (62) | 118 (30) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 39 (10) |

| No. of sites involved at onset (%) | ||

| 1 or 2 | 328 (93) | 207 (53) |

| 3 | 24 (7) | 134 (35) |

| More than 3 | 0 | 47 (12) |

| Dose of prednisone at onset (%) | ||

| None | 165 (47) | 204 (53) |

| More than 0 but less than 0.5 mg/kg | 92 (26) | 85 (22) |

| 0.5-1.0 mg/kg | 56 (16) | 60 (15) |

| More than 1.0 mg/kg | 39 (11) | 39 (10) |

| Platelet count less than 100 000/μL at onset, no. (%) | 173 (49) | 165 (43) |

| Serum bilirubin level more than 2 mg/dL at onset, no. (%) | 60 (17) | 58 (15) |

| Characteristic . | Acute onset (n = 352) . | Chronic onset (n = 388) . |

|---|---|---|

| Median time from transplantation to diagnosis, mo (range) | 3.6 (2.4-20.9) | 4.4 (2.2-28.2) |

| Type of onset, no. (%) | ||

| De novo (late*) | 43 (12) | 66 (17) |

| Quiescent (recurrent*) | 265 (75) | 264 (68) |

| Progressive (persistent*) | 44 (13) | 58 (15) |

| Sites involved at onset, no. (%) | ||

| Skin | 190 (54) | 261 (67) |

| Eyes | 0 | 92 (24) |

| Mouth | 0 | 333 (86) |

| Liver | 106 (30) | 136 (35) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 218 (62) | 118 (30) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 39 (10) |

| No. of sites involved at onset (%) | ||

| 1 or 2 | 328 (93) | 207 (53) |

| 3 | 24 (7) | 134 (35) |

| More than 3 | 0 | 47 (12) |

| Dose of prednisone at onset (%) | ||

| None | 165 (47) | 204 (53) |

| More than 0 but less than 0.5 mg/kg | 92 (26) | 85 (22) |

| 0.5-1.0 mg/kg | 56 (16) | 60 (15) |

| More than 1.0 mg/kg | 39 (11) | 39 (10) |

| Platelet count less than 100 000/μL at onset, no. (%) | 173 (49) | 165 (43) |

| Serum bilirubin level more than 2 mg/dL at onset, no. (%) | 60 (17) | 58 (15) |

New categorization of GVHD according to 2005 NIH consensus criteria.4

Major outcomes

The first question we addressed was whether major outcomes, including nonrelapse mortality, recurrent malignancy, overall mortality, and duration of systemic treatment differed between patients with NIH chronic GVHD compared with late acute GVHD. We found no statistically significant differences between the acute and chronic onset groups in the hazards of nonrelapse mortality, recurrent malignancy, overall mortality, or discontinued systemic treatment (Table 3). Among the 352 patients in the acute onset group, 100 (28%) subsequently developed manifestations that fulfilled NIH consensus criteria for chronic GVHD. The median interval time to development of manifestations that fulfilled NIH consensus criteria for chronic GVHD was 271 days (range, 12-1499 days). In this analysis, transitions from late acute GVHD to NIH chronic GVHD were not taken into account. The results show that the type of onset did not measurably affect the outcomes in these patients.

Major outcomes with NIH chronic GVHD compared with late acute GVHD at onset

| Outcome . | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) . | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)* . |

|---|---|---|

| Nonrelapse mortality | 1.02 (0.8-1.3) | 0.87 (0.6-1.2) |

| Recurrent malignancy | 0.76 (0.6-1.1) | 0.98 (0.7-1.5) |

| Overall mortality | 0.92 (0.7-1.1) | 0.84 (0.6-1.1) |

| Discontinued systemic treatment | 0.91 (0.7-1.1) | 1.09 (0.8-1.4) |

| Outcome . | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) . | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)* . |

|---|---|---|

| Nonrelapse mortality | 1.02 (0.8-1.3) | 0.87 (0.6-1.2) |

| Recurrent malignancy | 0.76 (0.6-1.1) | 0.98 (0.7-1.5) |

| Overall mortality | 0.92 (0.7-1.1) | 0.84 (0.6-1.1) |

| Discontinued systemic treatment | 0.91 (0.7-1.1) | 1.09 (0.8-1.4) |

In these models, transition from late acute GVHD at onset to NIH chronic GVHD was not considered as a competing risk.

The adjusted analysis accounts for the effects of de novo, quiescent or progressive onset, prednisone dose at onset, platelet count at onset, prior acute GVHD before day 100, patient age, donor age, number of HLA mismatches, female donors for male recipients, mobilized blood cell grafts, transplantation year, or number of organs affected by GVHD at onset.

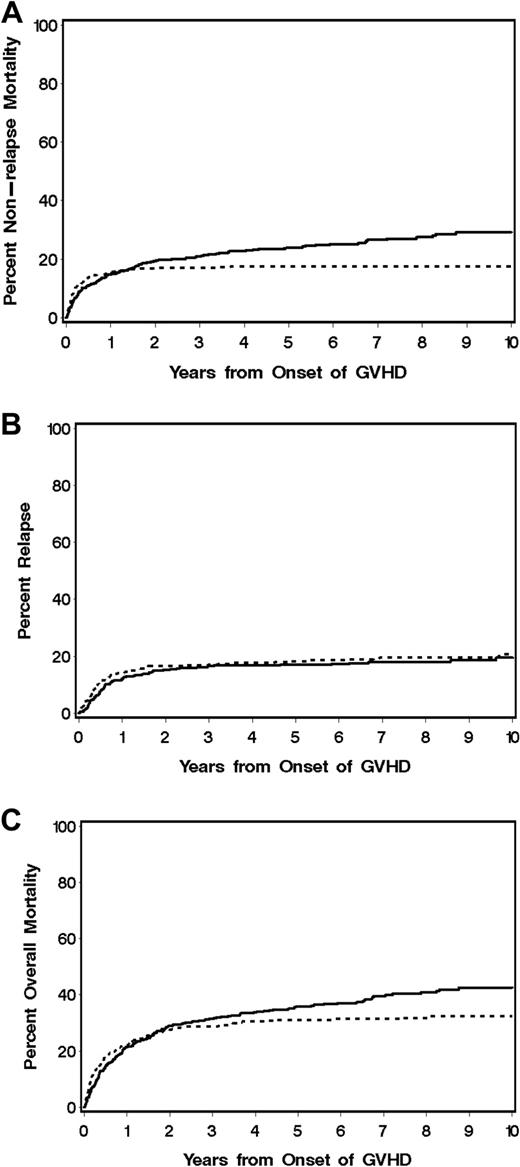

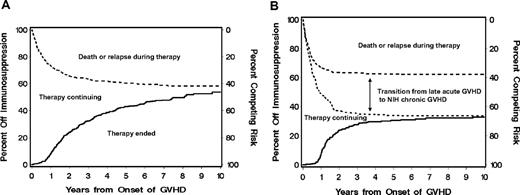

In an effort to assess potential biologic differences between NIH chronic GVHD and late acute GVHD, a separate analysis was carried out to determine whether event rates differed between these 2 syndromes. In this analysis, transition to NIH chronic GVHD was treated as a competing risk for patients in the acute onset group. In an unadjusted analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in the hazard of nonrelapse mortality or overall mortality in patients with NIH chronic GVHD at onset compared with patients with late acute GVHD at onset (excluding events that occurred after transition to NIH chronic GVHD). In this analysis, NIH chronic GVHD was associated with a somewhat lower risk of recurrent malignancy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74; 95% CI, 0.5-1.0; P = .07) and a lower rate of discontinued systemic treatment (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.5-0.8; P < .001) compared with late acute GVHD (Table 4 and Figures 1–2). HR estimates for recurrent malignancy and discontinued systemic treatment were attenuated when the analysis was adjusted for differences in other covariates. After accounting for these factors, the model showed no statistically significant associations between type of GVHD and any of the endpoints evaluated, although the rate of discontinued systemic treatment was somewhat lower for NIH chronic GVHD than for late acute GVHD (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.6-1.0; P = .08).

Major outcomes during NIH chronic GVHD compared with late acute GVHD

| Outcome without risk factors . | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) . | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)* . |

|---|---|---|

| Nonrelapse mortality | 1.23 (0.9-1.7) | 1.02 (0.7-1.5) |

| Recurrent malignancy | 0.74 (0.5-1.0) | 0.94 (0.6-1.4) |

| Overall mortality | 1.01 (0.8-1.3) | 0.90 (0.7-1.2) |

| Discontinued systemic treatment | 0.60 (0.5-0.8) | 0.76 (0.6-1.0) |

| Outcome without risk factors . | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) . | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)* . |

|---|---|---|

| Nonrelapse mortality | 1.23 (0.9-1.7) | 1.02 (0.7-1.5) |

| Recurrent malignancy | 0.74 (0.5-1.0) | 0.94 (0.6-1.4) |

| Overall mortality | 1.01 (0.8-1.3) | 0.90 (0.7-1.2) |

| Discontinued systemic treatment | 0.60 (0.5-0.8) | 0.76 (0.6-1.0) |

In these models, transition from late acute GVHD at onset to NIH chronic GVHD was considered as a competing risk.

Covariates used for adjustment are listed in Table 3.

Outcomes according to acute or chronic GVHD at initial presentation. Cumulative incidence of (A) nonrelapse mortality and (B) recurrent malignancy and (C) overall survival are shown for patients who presented initially with chronic GVHD according to NIH criteria (n = 388; —) compared with those who presented initially with late acute GVHD (n = 352;  ). In all 3 panels, progression to NIH chronic GVHD was treated as a competing risk for patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD.

). In all 3 panels, progression to NIH chronic GVHD was treated as a competing risk for patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD.

Outcomes according to acute or chronic GVHD at initial presentation. Cumulative incidence of (A) nonrelapse mortality and (B) recurrent malignancy and (C) overall survival are shown for patients who presented initially with chronic GVHD according to NIH criteria (n = 388; —) compared with those who presented initially with late acute GVHD (n = 352;  ). In all 3 panels, progression to NIH chronic GVHD was treated as a competing risk for patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD.

). In all 3 panels, progression to NIH chronic GVHD was treated as a competing risk for patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD.

Cumulative incidence of discontinued systemic treatment. (A) The cumulative incidence of discontinued systemic treatment among patients who presented NIH chronic GVHD (—) and the competing risks of death or recurrent malignancy during systemic treatment ( ). (B) The cumulative incidence of discontinued systemic treatment among patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD (—), together with the competing risks of death or recurrent malignancy during systemic treatment with (

). (B) The cumulative incidence of discontinued systemic treatment among patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD (—), together with the competing risks of death or recurrent malignancy during systemic treatment with ( ) or without (- - -) the additional competing risk of transition to NIH chronic GVHD. Areas in each panel are labeled according to the initial event after starting treatment. The “Therapy continuing” areas include only patients without a competing event.

) or without (- - -) the additional competing risk of transition to NIH chronic GVHD. Areas in each panel are labeled according to the initial event after starting treatment. The “Therapy continuing” areas include only patients without a competing event.

Cumulative incidence of discontinued systemic treatment. (A) The cumulative incidence of discontinued systemic treatment among patients who presented NIH chronic GVHD (—) and the competing risks of death or recurrent malignancy during systemic treatment ( ). (B) The cumulative incidence of discontinued systemic treatment among patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD (—), together with the competing risks of death or recurrent malignancy during systemic treatment with (

). (B) The cumulative incidence of discontinued systemic treatment among patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD (—), together with the competing risks of death or recurrent malignancy during systemic treatment with ( ) or without (- - -) the additional competing risk of transition to NIH chronic GVHD. Areas in each panel are labeled according to the initial event after starting treatment. The “Therapy continuing” areas include only patients without a competing event.

) or without (- - -) the additional competing risk of transition to NIH chronic GVHD. Areas in each panel are labeled according to the initial event after starting treatment. The “Therapy continuing” areas include only patients without a competing event.

Risk factor comparisons for nonrelapse mortality and discontinued systemic treatment

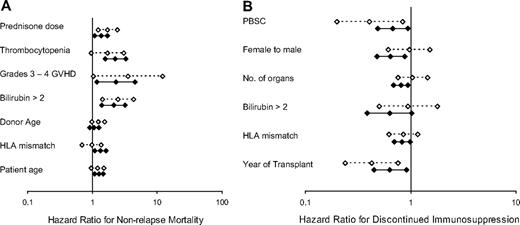

The second question we addressed was whether risk factors associated with nonrelapse mortality and duration of systemic treatment differed between patients with NIH chronic GVHD compared with late acute GVHD. In our previously published study,5 we identified 7 covariates significantly associated with increased risk nonrelapse mortality. Except for donor age, all of these associations between covariates and outcome held true in an update that accounted for additional nonrelapse deaths after the previous analysis (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). With the exception of donor age, all of these risk factors were associated with nonrelapse mortality among patients with NIH chronic GVHD; and with the exception of HLA-mismatching, all were associated with nonrelapse mortality among patients with late acute GVHD (Figure 3A).

Risk factor comparisons. (A) Nonrelapse mortality. (B) Discontinued systemic treatment. Hazard ratio estimates and 95% confidence limits for each risk factor are shown for patients with chronic GVHD according to NIH criteria (n = 488; solid lines, filled symbols) and for patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD (n = 352; dashed lines, open symbols). Progression to NIH chronic GVHD was treated as a competing risk in the analysis of late acute GVHD, and the analysis of NIH chronic GVHD began when manifestations of GVHD first fulfilled NIH consensus criteria for the diagnosis.

Risk factor comparisons. (A) Nonrelapse mortality. (B) Discontinued systemic treatment. Hazard ratio estimates and 95% confidence limits for each risk factor are shown for patients with chronic GVHD according to NIH criteria (n = 488; solid lines, filled symbols) and for patients who presented initially with late acute GVHD (n = 352; dashed lines, open symbols). Progression to NIH chronic GVHD was treated as a competing risk in the analysis of late acute GVHD, and the analysis of NIH chronic GVHD began when manifestations of GVHD first fulfilled NIH consensus criteria for the diagnosis.

We evaluated the duration of systemic treatment among 348 patients who discontinued systemic treatment after resolution of GVHD and before recurrent malignancy or death. The median duration of systemic treatment from time of original onset was 28.7 months (range, 0.9-115 months) among the 235 patients with NIH chronic GVHD at any time, compared with 15.6 months (range, 2-112 months) among the 113 patients who had only late acute GVHD and never had NIH chronic GVHD.

In the previous study, we identified 6 covariates significantly associated with prolonged systemic treatment. Except for the number of sites affected by chronic GVHD, all of these associations between covariates and outcome held true in an update that accounted for additional patients who discontinued systemic treatment after the previous analysis (supplemental Table 2). Although all 6 risk factors were associated with prolonged systemic treatment among patients with NIH chronic GVHD, 3 of these risk factors (female donor for male recipient, number of organs or sites involved with GVHD, and serum total bilirubin concentration > 2.0 mg/dL at diagnosis) were clearly not associated with prolonged systemic treatment among patients with late acute GVHD (Figure 3B).

Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with outcomes among patients with chronic GVHD by NIH consensus criteria

A multivariate analysis identified 8 covariates that were significantly associated with increased risk of nonrelapse mortality among patients with NIH chronic GVHD (Table 5). Six of these covariates were identified in the previous study, including onset of chronic GVHD during treatment with higher doses of prednisone, platelet count less than 100 000/μL at onset of chronic GVHD, serum bilirubin more than 2 mg/dL at onset of chronic GVHD, acute GVHD before day 100, older patient age, and recipient HLA mismatching. In addition, antecedent late acute GVHD (HR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.4-4.2; P = .002) and female donor for male recipient (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.0-2.2; P = .04) were significantly associated with increased risk of nonrelapse mortality among patients with NIH chronic GVHD. Donor age was significantly associated with risk of nonrelapse mortality in the previous study but not among patients with NIH chronic GVHD.

Risk factors associated with outcomes after NIH chronic GVHD

| . | Hazard ratio (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| Nonrelapse mortality* | ||

| Platelet count less than 100 000/μL at onset | 2.38 (1.6-3.5) | < .001 |

| Prednisone dose category at onset, per group | 1.74 (1.4-2.2) | < .001 |

| Total serum bilirubin concentration more than 2 mg/dL at onset | 2.10 (1.4-3.2) | .001 |

| Patient age, per 10 years | 1.33 (1.2-1.5) | < .001 |

| Acute GVHD before day 100, vs grades 0-I | .008 | |

| Grade II | 1.19 (0.6-2.2) | |

| Grades III-IV | 2.15 (1.1-4.2) | |

| Antecedent late acute GVHD | 2.45 (1.4-4.2) | .002 |

| No. of HLA-mismatched loci, per locus | 1.31 (1.1-1.6) | .01 |

| Female donor for male recipient | 1.49 (1.0-2.2) | .04 |

| Discontinued systemic treatment† | ||

| Antecedent late acute GVHD | 0.35 (0.2-0.6) | < .001 |

| G-CSF–mobilized blood as source of stem cells | 0.57 (0.4-0.8) | .001 |

| Total serum bilirubin concentration more than 2 mg/dL at onset | 0.62 (0.4-1.0) | .04 |

| Prednisone dose category at onset, per group | 0.63 (0.5-0.8) | .001 |

| Female donor for male recipient | 0.66 (0.5-0.9) | .006 |

| No. of sites involved at onset (except skin) | 0.67 (0.6-0.8) | < .001 |

| Donor age, per 10 years | 1.13 (1.0-1.3) | .02 |

| No. of HLA-mismatched loci, per locus | 0.84 (0.7-1.0) | .04 |

| . | Hazard ratio (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| Nonrelapse mortality* | ||

| Platelet count less than 100 000/μL at onset | 2.38 (1.6-3.5) | < .001 |

| Prednisone dose category at onset, per group | 1.74 (1.4-2.2) | < .001 |

| Total serum bilirubin concentration more than 2 mg/dL at onset | 2.10 (1.4-3.2) | .001 |

| Patient age, per 10 years | 1.33 (1.2-1.5) | < .001 |

| Acute GVHD before day 100, vs grades 0-I | .008 | |

| Grade II | 1.19 (0.6-2.2) | |

| Grades III-IV | 2.15 (1.1-4.2) | |

| Antecedent late acute GVHD | 2.45 (1.4-4.2) | .002 |

| No. of HLA-mismatched loci, per locus | 1.31 (1.1-1.6) | .01 |

| Female donor for male recipient | 1.49 (1.0-2.2) | .04 |

| Discontinued systemic treatment† | ||

| Antecedent late acute GVHD | 0.35 (0.2-0.6) | < .001 |

| G-CSF–mobilized blood as source of stem cells | 0.57 (0.4-0.8) | .001 |

| Total serum bilirubin concentration more than 2 mg/dL at onset | 0.62 (0.4-1.0) | .04 |

| Prednisone dose category at onset, per group | 0.63 (0.5-0.8) | .001 |

| Female donor for male recipient | 0.66 (0.5-0.9) | .006 |

| No. of sites involved at onset (except skin) | 0.67 (0.6-0.8) | < .001 |

| Donor age, per 10 years | 1.13 (1.0-1.3) | .02 |

| No. of HLA-mismatched loci, per locus | 0.84 (0.7-1.0) | .04 |

In this model, recurrent malignancy was treated as a competing risk. Follow-up was censored for patients who had recurrent malignancy before death. P values are derived from the likelihood ratio test.

Hazard ratios less than 1.0 indicate a lower rate of discontinued treatment, resulting in prolonged systemic treatment in the presence of the indicated risk factor compared with its absence. In this model, death and recurrent malignancy were treated as competing risks. Follow-up was censored for patients who died or had recurrent malignancy before systemic treatment was discontinued. P values are derived from the likelihood ratio test.

A multivariate analysis identified 7 covariates that were significantly associated with prolonged systemic treatment among patients with NIH chronic GVHD (Table 5). Five of these were identified in the previous study, including female donor for male recipient, serum bilirubin more than 2 mg/dL at onset, the use of growth-factor mobilized blood cells, the number of sites involved at onset, and the number of recipient HLA mismatches. In addition, antecedent late acute GVHD (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.2-0.6; P < .001) and onset of NIH chronic GVHD during treatment with higher doses of prednisone (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.5-0.8; P = .001) were significantly associated with prolonged systemic treatment. In this analysis, older donor age was significantly associated with a shorter duration of systemic treatment (HR, 1.13 per decade; 95% CI, 1.0-1.3; P = .02).

Discussion

When we embarked on the current study, we expected that patients with chronic GVHD defined by NIH criteria would have better survival, longer duration of systemic treatment, and lower risk of recurrent malignancy, compared with patients with late acute GVHD. We also expected that the profile of previously defined risk factors for prolonged systemic treatment and risk of nonrelapse mortality might differ for patients with chronic GVHD defined by NIH criteria compared with those with late acute GVHD. Contrary to these expectations, we found that the outcomes among patients in our cohort did not show statistically significant differences according to the presence or absence of NIH criteria for chronic GVHD, and profiles of risk factors for prolonged systemic treatment and risk of nonrelapse mortality showed more similarity than differences among patients with chronic GVHD that met the NIH criteria compared with those with late acute GVHD. Our results cannot be extrapolated broadly because our study population was limited to patients who received systemic treatment for historically defined chronic GVHD after myeloablative conditioning regimens and, predominantly, after bone marrow transplantation between 1994 and 2000. Further studies will be needed to compare outcomes between late acute and NIH chronic GVHD for patients who have not required systemic therapy. In addition, it remains to be determined whether major outcomes between late acute compared with NIH chronic GVHD will be different or not after nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, after peripheral blood or cord blood transplantations, and in a more contemporaneous patient population.

Our results provide only minimum estimates of the proportions of patients with manifestations that met NIH criteria for chronic GVHD at onset (52%) or at any time (66%). Because many of our patients live at great distances from Seattle, we use a “referral” or “consultation” model for clinical care after transplantation. Patients have comprehensive evaluations in Seattle at 80 to 100 days after transplantation and at one year after transplantation. In some cases, patients are able to return at 1- to 3-month intervals for management of chronic GVHD, but care for most patients is managed indirectly through collaboration with referring physicians who are not experts in the evaluation of chronic GVHD.

Telemedicine offered by our LTFU program is commonly used by our patients and their referring physicians. The notes and correspondence from this telemedicine collaboration provide additional documentation regarding chronic GVHD.

In the current study, we relied on this clinical documentation to determine whether clinical manifestation of chronic GVHD met NIH criteria. For example, a note from a physician or other medical provider or the information provided by a patient or a physician via telephone might indicate that a patient had a new rash and diarrhea requiring systemic treatment. In the absence of detailed information describing the presence of diagnostic or distinctive features such as lichen-planus or cutaneous sclerosis, we could not assume that the rash had characteristics of chronic GVHD according to NIH criteria. In this situation, we did not assign a diagnosis of chronic GVHD according to NIH criteria unless the records documented diagnostic or distinctive manifestations in other sites. The proportion of patients with late acute GVHD at onset was 48% in our study, higher than the 15% to 37% proportions reported in retrospective studies from centers where medical providers may have more frequent direct contact with patients.11-14 It is probable that our results overestimate the true proportion of patients with late acute GVHD because our analysis relied on available documentation, which might not have been sufficient to ascertain the presence of NIH criteria. Prospective studies with evaluation by appropriately trained medical providers will be needed to assess the true incidence and onset of NIH criteria among patients with GVHD more than 100 days after HCT.

Other investigators have evaluated the NIH criteria by assessing outcomes among patients with historically defined chronic GVHD.11-14 Three previous studies showed an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality or worse overall survival among patients with late acute GVHD at onset compared with those with classic chronic GVHD or overlap syndrome at onset.11,12,14 Our results are similar to those reported by Cho et al,13 who found no statistically significant differences in “GVHD-specific survival” between patients with late acute GVHD compared with those with NIH chronic GVHD at onset. The discrepant results among these studies may be explained by differences in historical criteria used to make the diagnosis of chronic GVHD in the respective centers and by inadequacies of medical records in documenting the presence or absence of diagnostic and distinctive manifestations of chronic GVHD according to NIH consensus criteria. Prospective studies will be needed to determine the impact of the NIH consensus criteria on outcomes among patients with GVHD beyond day 100 after HCT.

One of the previous studies showed decreased survival among patients with overlap syndrome compared with classic chronic GVHD at onset according to NIH criteria,12 but other studies showed similar survival among patients in these 2 groups.13,14 Jagasia et al12 showed that the presence of acute GVHD manifestations was associated with decreased survival among patients with historically defined chronic GVHD. We could not analyze the association of acute GVHD manifestations with outcomes among patients with historically defined chronic GVHD for 2 reasons. First, in the absence of documentation of other diagnostic NIH chronic GVHD manifestation in the skin (ie, poikiloderma, lichen-planus or lichen sclerosis features, morphea) or in other organs (eg, oral lichen-planus), we classified all patients with skin involvement as having acute manifestations because erythema almost invariably occurs at some time in patients with skin involvement. Most patients had skin, liver, or gut involvement at onset of historically defined chronic GVHD, and the number of patients with no manifestations in the skin, liver, or gut was too small to allow meaningful correlations with outcomes. Second, our medical records did not contain enough information to allow a time-dependent analysis of acute GVHD manifestations as a risk factor for outcomes. In any case, we expect that the presence or absence of cutaneous erythema depends more on the intensity of the immunosuppressive regimen than on biologic determinants of cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD.

Other investigators have examined the global severity of GVHD according to NIH criteria as a risk factor for nonrelapse mortality or survival among patients with historically defined chronic GVHD, although the original purpose of this staging was to define the need for systemic treatment and to reflect clinical effects of chronic GVHD on the patient's functional status, and not to predict outcomes.13-15 We did not examine overall severity scores as a risk factor because information from the medical records was often not sufficient to assign a severity score for each organ for many patients in the current study. We found, however, that high serum bilirubin concentration at onset was associated with higher mortality in all patient subgroups. On the other hand, the number of involved sites was not identified as a risk factor for nonrelapse mortality among patients with chronic GVHD by NIH criteria.

Antecedent late acute GVHD is a previously unidentified risk factor associated with prolonged systemic treatment and also with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality among patients with NIH chronic GVHD. The association with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality corresponds with previous results showing decreased survival among patients with a progressive onset of historically defined chronic GVHD from acute GVHD. We speculate that antecedent acute GVHD is associated with prolonged inflammatory insult to target organs, a greater degree of accumulated tissue damage, and more profound immune dysregulation, making subsequent NIH chronic GVHD more difficult to control and contributing to increased risks of fatal infection or organ failure.

The 2005, the NIH consensus project was originally developed as a tool to be used in clinical trials.4 The consensus recommendations turned attention toward clinical manifestations rather than time from transplantation as the basis for diagnosing chronic GVHD, with the implication that clinical trials should be designed to enroll patients who meet NIH criteria. Our results support the consensus recommendations that, with appropriate stratification, clinical trials can include patients with late acute GVHD as well as those with NIH chronic GVHD. The true prognostic value of the distinction between late acute and NIH chronic GVHD according to the consensus new classification criteria on major GVHD outcomes should be tested in prospective clinical studies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Judy Campbell, RN, Colleen McKinnon, RN, Catherine Baker, RN, Kathy Erne, Gina Brooks, and Linda Guerrero for assistance with data collection as well as our patients for their participation in clinical trials and to the referring physicians and medical staff for their collaborative efforts in the excellent care provided to patients and families.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (grants CA18029 and HL36444). A.C.V. was supported by Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo (grant 06/59475-4).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: M.E.D.F. and P.J.M. designed the study, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the paper; B.E.S. performed the statistical analysis and reviewed the paper; A.C.V. and P.V.C. collected data for the study and reviewed the paper; P.A.C., H.-P.K., M.L.F., E.H.W., S.J.L., and F.R.A. reviewed the paper; and C.K.M. recorded the clinical and research data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mary E. D. Flowers, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109-1024; e-mail: mflowers@fhcrc.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal