Abstract

Deletion of TP53 gene, under routine assessment by fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis, connects with the worst prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The presence of isolated TP53 mutation (without deletion) is associated with reduced survival in CLL patients. It is unclear how these abnormalities are selected and what their mutual proportion is. We used methodologies with similar sensitivity for the detection of deletions (interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization) and mutations (yeast functional analysis) and analyzed a large consecutive series of 400 CLL patients; a subset of p53–wild-type cases (n = 132) was screened repeatedly during disease course. The most common type of TP53 inactivation, ie, mutation accompanied by deletion of the remaining allele, occurred in 42 patients (10.5%). Among additional defects, the frequency of the isolated TP53 mutation (n = 20; 5%) and the combination of 2 or more mutations on separate alleles (n = 5; 1.3%) greatly exceeded the sole deletion (n = 3; 0.8%). Twelve patients manifested defects during repeated investigation; in all circumstances the defects involved mutation and occurred after therapy. Monoallelic defects had a negative impact on survival and impaired in vitro response to fludarabine. Mutation analysis of the TP53 should be performed before each treatment initiation because novel defects may be selected by previous therapies.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most frequent of all leukemias in the Western world, still represents an incurable disease.1 Its highly variable clinical course is mostly determined by the combination of 2 major biologic factors that impact disease progression: mutation status of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region (IgVH) and 4 prominent genomic aberrations, ie, deletions 11q22-23, 13q14, 17p13, and trisomy of chromosome 12.2,3 The deletion at region 17p13, which harbors a tumor-suppressor gene TP53 (coding for p53 protein), has been shown repeatedly and consistently to be associated with the worst prognosis in CLL patients.4,5 On the contrary, a good prognosis requires, among other factors, an intact TP53 gene,6 although some rare exceptions exist.7 A poor response to not only conventional DNA-damaging chemotherapy but also to its combination with rituximab is one of the major determinants for an inferior outcome in TP53-affected patients.8,9 These patients are current candidates for alternative treatment approaches, which include submission to clinical trials that investigate drugs with p53-independent mechanisms of action, therapy by monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab, and stem cell transplantation.10-12

It is estimated that approximately half of all cancers lose their wild-type (wt)-p53 activity at a certain point in development.13 The high pressure on the elimination of the p53 protein during tumor progression stems from its central role in several divergent yet interconnected processes, including the cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, DNA repair, and senescence.14 In addition to its well-established role in cancer, the p53 is currently recognized as an important player in some of the other types of cellular stress, eg, in ischemia disease or aging of an organism.15

The level of p53 protein in a cell is regulated through a direct binding to the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2, whose expression is induced by the p53.16 This autoregulatory feedback loop is interrupted in the case of an initiation of DNA double-strand breaks by ATM and Chk2 kinases, which induce phosphorylation of the p53 at residues critical for MDM2 binding.17 The ATM–Chk2–p53 axis has been proven as part of the fundamental DNA-damage response anticancer barrier, which is activated by impairment of the DNA in precancerous lesions and compromised later by mutations during a malignant conversion.18

Although the TP53 was originally considered to be a recessive tumor suppressor, several precise studies have shown a profound effect of one allele loss or its inactivation by a sole mutation on tumorigenesis. An analysis of tumors in heterozygous (p53+/−) mice showed that many of the tumors preserved a wt TP53 allele, documenting the role of the p53 haploinsufficiency (gene dosage effect) in cancer progression.19 However, the missense mutation analogous to human R175H hot-spot alteration introduced into a mouse led to a significantly greater metastatic potential of the developed tumors in comparison with the p53(+/−) mice.20 Besides the TP53 defects, an attenuation of p53 activity and a predisposition to tumor formation also was proven to occur through enhanced activity of the negative regulatory protein MDM2, harboring a polymorphism in its promoter (SNP309), which shows how critical the standard level of the p53 protein is for cancer prevention.21

Recently, several research groups have analyzed the impact of an isolated TP53 mutation (without accompanying deletion) on response to therapy, disease progression, and overall survival in CLL. Although the study by Grever et al22 did not find any significant role of the sole TP53 mutation in response to fludarabine-based therapy, 3 other reports correlated single TP53 mutation with complex aberrant karyotype and rapid disease progression23 and also with poor survival and chemorefractoriness.24,25

We analyzed the presence of TP53 abnormalities in a consecutive series of 400 CLL patients, including the repeated monitoring of this gene in 132 of them. For the detection of chromosomal deletions and the identification of mutations, we used the methodologies with similar sensitivity, ie, interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (I-FISH) and functional analysis of separated alleles in yeasts (FASAY), respectively. In our report we show that TP53 mutation and not deletion is preferentially selected in CLL. We also present a strong association between the presence of therapy and the occurrence of novel TP53 abnormalities and show that isolated TP53 missense mutations impair the primary response of the CLL cells to DNA damage.

Methods

CLL patients

The study was performed on blood samples of 400 CLL patients monitored and/or treated at the Department of Internal Medicine–Hematooncology, University Hospital Brno, during the years 2003 to 2008; a subset was obtained in collaboration with the Department of Hematology, J. G. Mendel Cancer Center at Novy Jicin, Czech Republic. All blood samples were processed with written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under protocols approved by the Ethical Commission of the University Hospital Brno. Clinical and biologic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical and biologic characteristics of CLL patients

| Characteristic . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Patients, n | 400 |

| Median age at diagnosis, y | 60 |

| Women/men, % | 35/65 |

| Stage at time of TP53 and ATM examination (n = 365), % | |

| Low risk: Rai stage 0 | 30 |

| Intermediate risk: Rai stage I/II | 36 |

| High risk: Rai stage III/IV | 34 |

| IgVH, % (n = 355) | |

| Mutated | 38 |

| Unmutated | 62 |

| I-FISH according to the hierarchical classification of Döhner et al26 (n = 400), % | |

| 17p− | 11 |

| 11q− | 21 |

| +12 | 11 |

| 13q− | 34 |

| Normal | 23 |

| Investigation of TP53 and ATM status, % | |

| At time of diagnosis | 48 |

| During course of disease | 52 |

| Therapy before the first TP53 and ATM examination, % | |

| No | 73 |

| Yes | 27 |

| Characteristic . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Patients, n | 400 |

| Median age at diagnosis, y | 60 |

| Women/men, % | 35/65 |

| Stage at time of TP53 and ATM examination (n = 365), % | |

| Low risk: Rai stage 0 | 30 |

| Intermediate risk: Rai stage I/II | 36 |

| High risk: Rai stage III/IV | 34 |

| IgVH, % (n = 355) | |

| Mutated | 38 |

| Unmutated | 62 |

| I-FISH according to the hierarchical classification of Döhner et al26 (n = 400), % | |

| 17p− | 11 |

| 11q− | 21 |

| +12 | 11 |

| 13q− | 34 |

| Normal | 23 |

| Investigation of TP53 and ATM status, % | |

| At time of diagnosis | 48 |

| During course of disease | 52 |

| Therapy before the first TP53 and ATM examination, % | |

| No | 73 |

| Yes | 27 |

CLL indicates chronic lymphocytic leukemia; and I-FISH, interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Identification of mutations in the TP53 gene

All patients in the study (n = 400) were screened by the functional yeast analysis FASAY27 ; a subset (n = 132) was examined repeatedly. In this assay, the central part of the TP53 gene (amplified from cDNA between exons 4 and 10, ie, codons 42 to 374) is introduced into an ADE2− yeast strain carrying a reporter with a p53-binding site upstream of the ADE2 gene. On the plates containing a low level of adenine, the p53 wt samples form large white colonies, whereas the colonies with the p53 mutations (mut-p53) are small and red, which is attributable to limited growth and an accumulation of a reddish product of adenine metabolism. Samples containing a wt-TP53 gene account for 90% or more of the white colonies in the assay; the remaining 10% represent background, a consequence of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–induced mutations or a low-quality RNA. We have shown previously28 that the use of FASAY provides the expected number of red colonies when serial dilutions of wt-TP53 and mut-TP53 plasmids for PCR amplification or when leukemic cell lines with known p53 status are used. We can also observe, on a long-term basis, that in properly handled clinical samples (which allow for standard PCR amplification) the background of the FASAY is less than 10%. In samples that provided more than 10% of red or pink colonies, we sequenced DNA templates isolated from 4 to 6 individual colonies to identify a clonal TP53 mutation. The pink colonies are supposed to harbor a temperature-sensitive TP53 mutation.29 In the case of exon deletion, direct sequencing of genomic DNA was used to find the corresponding mutation. We found that, when using FASAY, we were not able to identify the CLL hot-spot 2-nt deletion in codon 209 (exon 6), probably because of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of this particular molecule.30 Therefore, we also supplemented the use of FASAY by high-resolution melting analysis of the exon 6 in 90 patients. The high-resolution melting was done by the use of Rotor-Gene6000 (QIAGEN). The exact conditions can be provided on request.

Other genetic characterizations of CLL cells

Deletions at the 11q22-q23 (ATM) and 17p13 (TP53) loci were detected by I-FISH by the use of locus-specific probes from Abott Vysis Inc, according to the manufacturer's instructions. At least 200 interphase nuclei per slide were evaluated with an Olympus BX61 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Vosskuhler 1300D digital camera and LUCIA-KARYO/FISH/CGH imaging system (Laboratory Imaging). The cut-off level for the detection of both TP53 and ATM deletions (5%) was calculated in a series of 15 samples obtained from normal bone-marrow donors (200 interphase nuclei per slide were evaluated) by use of the upper limit of binomial confidence interval. PCR and direct sequencing were used to analyze the IgVH rearrangements and mutation status.

Western blot analysis of p53

The p53 protein was detected with anti-p53 antibody DO-1 (a gift from Dr Vojtesek, MMCI Brno); PCNA protein was used as an internal standard; antibody Mab424R (Chemicon). The procedure was as previously described.31

Viability testing after in vitro fludarabine administration

Samples, which had been vitally frozen in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored in liquid nitrogen, were exclusively used. Cells were kept in tissue culture under standard conditions for 24 hours (37°C, 5% CO2) and then used for the metabolic WST-1 assay (Roche, CH). The procedure was as previously described.31

Real-time quantitative PCR of the p53 target genes

A quantitative reverse-transcription PCR assay was performed by use of TaqMan technology and the 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The primer and probe sets were specific for the BAX, BBC3 (PUMA), and CDKN1A (p21) genes (TaqMan Gene Expression Assay; Applied Biosystems). The geometric mean of TBP (TATAA-box binding protein) and HPRT1 (hypoxanthine–guanine phosphoribosyltransferase) values served as an internal standard. The procedure was as previously described.31

Statistical evaluation

The χ2 test was used to assess the association between genetic defects and (1) the Rai stage and (2) the mutation status of IgVH. The Fisher exact test was used for assessing the association among (1) TP53 defects and ATM deletion; (2) the presence of therapy and novel TP53 abnormalities; and (3) genetic abnormalities and requirement for therapy. Survival analysis was performed with the use of the Kaplan-Meier survival estimator. The response of CLL cells to fludarabine was evaluated by a 2-factor analysis of variance with the subsequent Tukey HSD post-hoc test.

Results

Characterization of the CLL cohort

The investigation of the TP53 gene (mutation and deletion) and the ATM gene (deletion) from the same exact time of examination was performed in a consecutive series of 400 patients. The mutation status of the IgVH locus (Table 1) indicated a more unfavorable profile of the cohort in comparison with the other studies; 62% of the patients harbored the unmutated IgVH sequence (the reported ratio is usually 1:1 or that in favor of mutated IgVH). The reason for this bias is a local concentration of patients with inferior CLL at the University Hospital Brno; noncomplicated patients are monitored at regional hematologic centers in the Czech Republic.

Single TP53 mutation but not single deletion is notably selected in CLL cells

The TP53 gene was impaired in 70 patients (17.5%). A somewhat greater frequency than in other CLL studies (usually around 10%) should be assigned to (1) the previously discussed more-unfavorable profile of the cohort; (2) repeated investigation of TP53 status in the subset of p53-wt patients (n = 132) during the course of the disease—this additional screening, which provided 12 novel abnormalities, is discussed later in the text; and (3) use of the highly sensitive FASAY analysis. The types of TP53 defects are summarized in Table 2. Chromosomal deletions were present in 45 patients (11.3%), with the single deletion—without accompanying mutation on the remaining allele—being extremely rare (3 cases; 0.8%). In contradiction to this finding, a single TP53 mutation was detected in 20 patients (5.0%), and 5 patients (1.3%) harbored at least 2 different mutations on separate alleles. The biallelic, but not monoallelic TP53 abnormalities, were clearly associated with the high-risk (Rai III/IV) CLL (Table 2; P < .001 and P = .13, respectively); both biallelic and monoallelic TP53 defects were associated with the unmutated IgVH locus (Table 2; P < .001 and P = .025, respectively). The identified mutations are listed in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The alterations consisted mostly of missense mutations (77%), with the mutational hot-spots being codons 248 (5 cases), followed by codons 132, 175, and 234.

Summary of TP53 abnormalities identified in CLL patients and their association with biologic and clinical variables

| Abnormality . | Monoallelic alterations . | Biallelic alterations . |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 23 | 47 |

| Type of defect (n) | del(17p) (3), mutation (20) | del(17p)/mutation (42), mutation/mutation (5) |

| Proportion of missense mutations, % | 100 | 67* |

| High risk: Rai stage III/IV (at the time of TP53 status examination), % (n) | 48 (10/21) | 67 (29/43) |

| P | .13 | < .001 |

| Unmutated IgVH, % (n) | 86 (18/21) | 93 (41/44) |

| P | .025 | .001 |

| 11q deletion, % (n) | 43 (10/23) | 11 (5/47) |

| P | .014 | .055 |

| Abnormality . | Monoallelic alterations . | Biallelic alterations . |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 23 | 47 |

| Type of defect (n) | del(17p) (3), mutation (20) | del(17p)/mutation (42), mutation/mutation (5) |

| Proportion of missense mutations, % | 100 | 67* |

| High risk: Rai stage III/IV (at the time of TP53 status examination), % (n) | 48 (10/21) | 67 (29/43) |

| P | .13 | < .001 |

| Unmutated IgVH, % (n) | 86 (18/21) | 93 (41/44) |

| P | .025 | .001 |

| 11q deletion, % (n) | 43 (10/23) | 11 (5/47) |

| P | .014 | .055 |

P = .003 (biallelic vs monoallelic alterations in relation to 11q deletion).

CLL indicates chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

In the subgroup del(17p)/mutation.

In contrast to biallelic TP53 changes involving cytogenetic deletion, which contained on the other allele missense mutation (n = 28), frame-shift (n = 8) or in-frame deletion (n = 3), insertion (n = 1), and mutation affecting the exon/intron splicing site (n = 2), all 20 monoallelic mutational alterations represented missense substitutions. It points to their selection advantage, likely ensured by a dominant negative effect toward wt allele or a gain of function.32 Moreover, in 2 cases in which the number of red colonies significantly exceeded 60% (complete inactivation of one allele plus background; supplemental Table 1), the presence of uniparental disomy (UPD) in the TP53 locus could be considered. UPD has been observed recently in CLL patients as a frequent event and should lead to a phenotype comparable with the complete p53 inactivation.33 Finite evidence for UPD would have to be provided, however, by the use of a single nucleotide polymorphism-based array. In 11 patients with a single mutation, we once again performed FASAY after a certain period (median, 9 months; range, 4-29 months) and confirmed in all cases the mutated phenotype; compatible FISH analyses were performed in 6 of the 11 cases and were always negative. Particular mutation was verified by sequencing in 9 cases and always confirmed.

Mutation of the TP53 gene often leads to the stabilization of the p53 protein because of an inability of the mutated p53 to induce expression of its own negative regulator MDM2. To gain insight into the functionality of p53 in affected cells, we assessed the level of the p53 protein in samples with sole missense mutations versus the samples harboring biallelic inactivation consisting of cytogenetic deletion and missense mutation. Although only 2 (17%) of 12 cases in the former group manifested a clearly detectable level of p53, in the latter subset the stabilization was substantially more frequent (21/24; 88%); only 1 wt-p53 sample of 250 tested showed the p53 level comparable with mutated cases (supplemental Figure 1 and data not shown). It indicates that most of the cases with isolated missense mutations preserve a substantial p53 activity toward at least some target promoters.

Monoallelic TP53 alterations are significantly associated with ATM deletion

Abnormalities of TP53 and ATM genes are considered to be mutually exclusive in CLL cells because dysfunction of one has been proven to be an alternative to the defect of the other.34 Therefore, we analyzed their relationship in our cohort, structured according to monoallelic versus biallelic TP53 inactivation. In the TP53-wt patients, heterozygous ATM deletion was detected in 74 (22%) of 330 patients. Similarly to TP53, the ATM deletion was significantly associated with the unmutated IgVH gene (65/68, 96%; P < .001). Interestingly, in the TP53-affected patients, the presence of accompanying ATM deletion was significantly associated with monoallelic alterations (43%; P = .014; Table 2). The presence of complete p53 inactivation, on the other hand, resulted in the reduced frequency of ATM deletion (11%; P = .055; Table 2). This finding suggests that the monoallelic abnormalities in the TP53 do not impair p53 protein completely and are coselected with accompanying defects in ATM.

Novel TP53 abnormalities appeared after the administration of therapy and always included mutation

Identifying TP53 changes early in their development may help to clear the selection preference with respect to deletion or mutation. Therefore, we repeatedly screened 132 patients with previously intact TP53 genes by FASAY to reveal novel mutations. The FISH analysis for del(17p) and del(11q) was available in 83% of the samples (109/132). Because it has been reported that p53 inactivation may occur as a consequence of previous DNA-damaging chemotherapy in CLL,35 we divided the cohort according to the presence of therapy in the period between the 2 investigations. Sixty-two patients received from 1 to 3 courses of chemo- (n = 22), chemoimmuno- (n = 30), or immunotherapy (n = 10). Seventy patients were devoid of any therapeutic intervention. The median of the proportion of CLL cells in the samples in investigation I was similar between the treated and untreated subgroups (87%, range, 20%-99% vs 88%, range, 25%-99%, respectively). The median time between investigations I and II was 33 months in the treated subgroup (range, 5-61 months) and 22 months in the untreated subgroup (range, 4-57 months). The median of CLL cells proportion in investigation II was also similar (83%, range, 21%-98% vs 89%, range, 47%-99%, respectively). However, the treated cohort manifested the following unfavorable factors: (1) a greater proportion of patients who received therapy before investigation I (44% vs 13%); (2) more patients in progression of the disease in investigation II (87% vs 57%); (3) more frequent unmutated status of IgVH (80% vs 42%); and (4) more cases with ATM deletion (n = 22 vs n = 10 in untreated cohort).

Novel TP53 abnormalities were detected in 12 patients; all received therapy between investigations I and II (P < .001). The median time of their investigation was 22 months, fully comparable with the untreated cohort, excluding an influence of this parameter on mutation occurrence. In all instances the mutation was selected, accompanying the remaining allele by deletion (n = 9), another mutation (n = 1), or no alteration (n = 2; Table 3). This observation further indicates that TP53 mutation and not deletion is a primary end point of selection in CLL cells. In 3 patients we detected a novel ATM deletion; 2 of the 3 patients were not treated between the investigations. It may show that ATM is not as closely associated with therapy as the p53; we emphasize, however, that we do not have information about the second ATM allele.

Novel TP53 abnormalities identified in CLL patients with originally intact gene (in investigation I)

| Patient . | Time between investigations, mo . | TP53 defect . | Mutation . | Therapy before mutation detection . | Survival, mo . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From time of abnormality detection . | From diagnosis . | |||||

| P1* | 33 | del/mut | del 1 nt in codon 294 | R, CHOP, R-CHOP | 1 | 129 |

| P2 | 7 | del/mut | R273H | CHOP, A, FC | 7 | 28 |

| P3* | 51 | del/mut | G244D | FCR | 2 | 68 |

| P4 | 37 | del/mut | del 22 nt in intron 5 (splice mutation) | FC | 3† | 103† |

| P5* | 10 | mut/mut | K132R/del 14 nt in codon 194 | A | 16 | 85 |

| P6 | 36 | del/mut | T211I | FC, A | 3 | 39 |

| P7 | 11 | wt/mut | I195T | FC, R-CHOP, CHOP, A | 27† | 48† |

| P8* | 18 | del/mut | R175H | FC | 16† | 102† |

| P9* | 19 | wt/mut | C275Y | A | 3 | 148 |

| P10* | 19 | del/mut | del 9 nt in codon 252 | CHOP | 32 | 52 |

| P11* | 24 | del/mut | ASHM | R-CHOP | 37 | 96 |

| P12* | 33 | del/2 mut | K120M/del 2 nt in codon 209 | FCR | 12 | 92 |

| Patient . | Time between investigations, mo . | TP53 defect . | Mutation . | Therapy before mutation detection . | Survival, mo . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From time of abnormality detection . | From diagnosis . | |||||

| P1* | 33 | del/mut | del 1 nt in codon 294 | R, CHOP, R-CHOP | 1 | 129 |

| P2 | 7 | del/mut | R273H | CHOP, A, FC | 7 | 28 |

| P3* | 51 | del/mut | G244D | FCR | 2 | 68 |

| P4 | 37 | del/mut | del 22 nt in intron 5 (splice mutation) | FC | 3† | 103† |

| P5* | 10 | mut/mut | K132R/del 14 nt in codon 194 | A | 16 | 85 |

| P6 | 36 | del/mut | T211I | FC, A | 3 | 39 |

| P7 | 11 | wt/mut | I195T | FC, R-CHOP, CHOP, A | 27† | 48† |

| P8* | 18 | del/mut | R175H | FC | 16† | 102† |

| P9* | 19 | wt/mut | C275Y | A | 3 | 148 |

| P10* | 19 | del/mut | del 9 nt in codon 252 | CHOP | 32 | 52 |

| P11* | 24 | del/mut | ASHM | R-CHOP | 37 | 96 |

| P12* | 33 | del/2 mut | K120M/del 2 nt in codon 209 | FCR | 12 | 92 |

A indicates alemtuzumab; ASHM, aberrant somatic hypermutations in the TP53 gene36 ; C, cyclophosphamide; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; F, fludarabin; and R, rituximab.

Patient also received therapy before investigation I.

Patient is alive.

Monoallelic TP53 abnormalities impair a survival of CLL patients

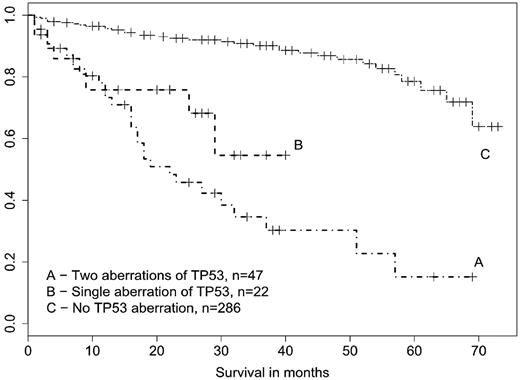

Although some TP53 abnormalities are present at diagnosis, many of them develop later during the course of the disease. They are considered as clonal variants, which increase substantially an aggressiveness of CLL. In line with that, survival of CLL patients who developed a novel TP53 defect in our study was dramatically shorter when assessed from the time of detection in comparison with survival from diagnosis (Table 3). We therefore created the survival curves from time of abnormality detection (TP53, ATM); date of investigation was used if a sample was wt. Median follow-up in living patients was 32.5 months. Both monoallelic and biallelic TP53 abnormalities significantly (P < .001) deteriorated patients survival compared with all TP53-wt cases combined together regardless of the ATM and IgVH status (Figure 1). However, the unmutated IgVH itself had a negative influence on survival (P < .001; data not shown), and as discussed previously, the high-risk genetic abnormalities (in TP53 or ATM genes) were derived almost exclusively from this subgroup.

Survival of CLL patients structured according to the TP53 defects. Survival was assessed from time of TP53 investigation. Patients with both biallelic and monoallelic TP53 defects showed significantly worse survival than p53 wt patients (P < .001).

Survival of CLL patients structured according to the TP53 defects. Survival was assessed from time of TP53 investigation. Patients with both biallelic and monoallelic TP53 defects showed significantly worse survival than p53 wt patients (P < .001).

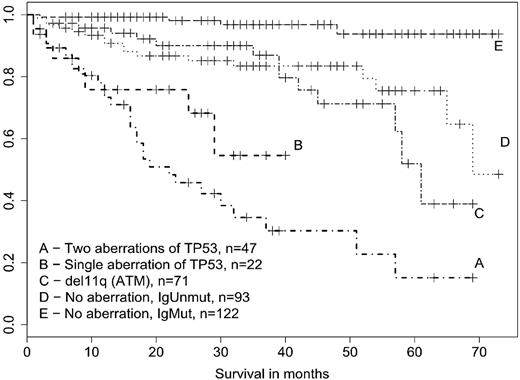

Therefore, we assessed the survival also in relation to the unmutated IgVH (Figure 2). In this case the biallelic TP53 defects showed a clear association with shorter survival (P < .001), whereas the monoallelic changes manifested a much weaker, albeit significant impact (P = .021) and ATM deletion had no effect at all (P = .55). The 2 patients with single TP53 mutation, but supposed UPD, were alive at the time of analysis and therefore the reduced survival of the corresponding subgroup cannot be attributed to them. Patients with monoallelic TP53 defects as a result constitute an independent prognostic subgroup, whose survival is substantially worse in comparison with patients possessing ATM deletion or unmutated IgVH with no accompanying high-risk abnormality.

Survival of CLL patients structured according to the TP53 defects, ATM deletion, and mutation status of IgVH. Survival was analyzed from time of TP53/ATM investigation. An effect of the abnormalities on survival was assessed in comparison with p53-wt/ATM-wt subgroup harboring the unmutated IgVH (curve D). Biallelic TP53 changes showed strong effect (P < .001), monoallelic TP53 abnormalities intermediate effect (P = .021), and ATM deletion no impact at all (P = .55).

Survival of CLL patients structured according to the TP53 defects, ATM deletion, and mutation status of IgVH. Survival was analyzed from time of TP53/ATM investigation. An effect of the abnormalities on survival was assessed in comparison with p53-wt/ATM-wt subgroup harboring the unmutated IgVH (curve D). Biallelic TP53 changes showed strong effect (P < .001), monoallelic TP53 abnormalities intermediate effect (P = .021), and ATM deletion no impact at all (P = .55).

In addition to survival, we also focused on the requirement for therapy within a 6-month period after the abnormality detection/wt investigation. The decision to use therapy in a particular patient was made according to the updated National Cancer Institute guidelines,37 ie, it was not influenced by the knowledge of TP53, ATM, or IgVH status. The data are summarized in Table 4. Therapy was significantly (P < .001) more frequently required in all 3 aberrant subgroups compared with wt patients, unstructured according to IgVH status. Similarly to overall survival, the unmutated IgVH itself was significantly associated with requirement for therapy (P = .001). When the unmutated IgVH was used as a control group, the statistical significance (P < .001) remained only for biallelic TP53 inactivation; there was only a trend (P = .09) for monoallelic TP53 defects and no difference at all for ATM deletion.

Requirement for therapeutic intervention within the 6-month period after detection of TP53/ATM abnormalities or investigation-wt in individual patient subgroups

| Status . | Group . | Treated . | Untreated . | Percentage of treated . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 biallelic inactivation | A | 37 | 6 | 86 | AF, < .001; AD, < .001 |

| TP53 monoallelic inactivation | B | 16 | 6 | 72 | BF, < .001; BD, .09 |

| Deletion of ATM | C | 41 | 32 | 56 | CF, < .001; CD, .47 |

| wt unmutated IgVH | D | 50 | 42 | 54 | DE, < .001 |

| wt mutated IgVH | E | 18 | 107 | 14 | |

| wt regardless of IgVH | F | 68 | 149 | 31 |

| Status . | Group . | Treated . | Untreated . | Percentage of treated . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 biallelic inactivation | A | 37 | 6 | 86 | AF, < .001; AD, < .001 |

| TP53 monoallelic inactivation | B | 16 | 6 | 72 | BF, < .001; BD, .09 |

| Deletion of ATM | C | 41 | 32 | 56 | CF, < .001; CD, .47 |

| wt unmutated IgVH | D | 50 | 42 | 54 | DE, < .001 |

| wt mutated IgVH | E | 18 | 107 | 14 | |

| wt regardless of IgVH | F | 68 | 149 | 31 |

IgVH indicates immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region; wt, wild-type; and AF, group A compared with group F, and so on.

Single TP53 missense mutation impairs a response of CLL cells to fludarabine

A large body of evidence shows that the crucial impact of p53 on the fate of CLL patients is tightly connected with its role in response to therapy. The nucleoside analog fludarabine currently represents a key drug for CLL and has been confirmed to elicit p53-dependent up-regulation of downstream target genes in CLL cells.38 Recently, Rossi et al25 showed an association of TP53 mutation, but not 17p deletion, with chemorefractoriness to fludarabine-based regimens. However, a direct comparison of primary in vitro response to fludarabine in CLL samples with monoallelic missense mutation versus biallelic TP53 defects has never been, according to our knowledge, performed. We used 4 different concentrations of fludarabine (25, 6.25, 1.6, and 0.4 μg/mL), which has shown earlier to provide a concentration-dependent curve of viability after 48 hours of treatment in most of the CLL samples.31 The testing of cellular viability is presented in Figure 3. The cells with both biallelic and monoallelic TP53 inactivation were significantly (P < .001) more resistant than wt cells. At a concentration of 1.6 μg/mL, which is comparable with a clinical situation,39 there was no difference between the biallelic and monoallelic TP53 defect. However, when the greater concentration of fludarabine was used, the cells with monoallelic defect showed intermediate viability.

Viability of CLL cells after in vitro administration of fludarabine. Metabolic WST-1 assay was used. Dark gray bars indicate biallelic TP53 defect (n = 7); Light gray bars, monoallelic TP53 defect (n = 7); white bars, no TP53 defect (n = 8); the last group consisted of 4 samples harboring ATM deletion and 4 purely wt samples with unmutated IgVH. The monoallelic TP53 defects (missense mutations) impaired the response to fludarabine in comparison with the other high-risk CLL factors, ie, deletion of ATM or unmutated IgVH locus.

Viability of CLL cells after in vitro administration of fludarabine. Metabolic WST-1 assay was used. Dark gray bars indicate biallelic TP53 defect (n = 7); Light gray bars, monoallelic TP53 defect (n = 7); white bars, no TP53 defect (n = 8); the last group consisted of 4 samples harboring ATM deletion and 4 purely wt samples with unmutated IgVH. The monoallelic TP53 defects (missense mutations) impaired the response to fludarabine in comparison with the other high-risk CLL factors, ie, deletion of ATM or unmutated IgVH locus.

In addition to viability testing, we also assessed the induction of p53-downstream target genes PUMA, BAX, and CDKN1A (coding for p21 protein) after fludarabine exposure in a subset of samples. The results are presented in Figure 4. Although the samples harboring biallelic TP53 inactivation lacked any induction, the response was quite heterogeneous in the cells with monoallelic defects: response to PUMA promoter was completely or substantially impaired in all of these samples (n = 6), whereas 3 cases induced expression of BAX and 1 case the CDKN1A gene in a manner similar to wt control.

Induction of p53-downstream target genes PUMA, BAX, and CDKN1A (p21) after fludarabine administration. Quantitative PCR data show induction related to untreated control (set at 100%). Fludarabine was used in the concentration 3.6 μg/mL for 24 hours. TP53-2A indicates biallelic TP53 inactivation; 1, del/R249G; 2, del/V216M; 3, del/L132R. TP53-1, monoallelic TP53 inactivation; 1, wt/L194R; 2, wt/Y234N; 3, wt/D281N; 4, wt/C176W; 5, wt/C277F; 6, wt/A138P; and WT, no TP53 abnormality.

Induction of p53-downstream target genes PUMA, BAX, and CDKN1A (p21) after fludarabine administration. Quantitative PCR data show induction related to untreated control (set at 100%). Fludarabine was used in the concentration 3.6 μg/mL for 24 hours. TP53-2A indicates biallelic TP53 inactivation; 1, del/R249G; 2, del/V216M; 3, del/L132R. TP53-1, monoallelic TP53 inactivation; 1, wt/L194R; 2, wt/Y234N; 3, wt/D281N; 4, wt/C176W; 5, wt/C277F; 6, wt/A138P; and WT, no TP53 abnormality.

Discussion

Defects in the TP53 gene are decidedly associated with the worst prognosis in CLL patients. Although the p53 dysfunction is routinely assessed as a monoallelic gene deletion when I-FISH is used, 2 recent reports by Zenz et al24 and Rossi et al25 have clearly shown an independent prognostic value of single TP53 mutation (without accompanying deletion) in CLL. These observations are important not only with respect to this leukemia but also for cancer research in general; the consequence of monoallelic TP53 defects for tumor progression (gene dosage effect in the case of deletion and assumed dominant negative effect on wt allele or potential gain of function in the case of mutation) is unclear and remains a matter of intense debate.32,40

In our study we confirm the detrimental impact of monoallelic TP53 aberrations on the survival of CLL patients, although survival was somewhat better than in patients with biallelic inactivation. In addition, our study shows that (1) single missense mutation but not single deletion is selected in CLL cells; (2) single TP53 abnormalities are frequently accompanied by ATM deletion; (3) novel TP53 abnormalities occur after therapy administration and always involve mutation; and (4) the single TP53 missense mutation significantly impairs p53-dependent DNA-damage response in CLL cells.

The question of preferential selection of monoallelic TP53 mutation versus 17p deletion was not addressed in the study by Zenz et al24 because of the small number of corresponding cases. A more extensive study by Rossi et al25 identified a large fraction of monoallelic TP53 changes within the affected cohort (total, n = 44) and showed that a single deletion was more frequent (16/44) than a single mutation (10/44). This finding is in sharp contrast to our results, where deletion without an accompanying mutation was a very rare event (3/70 of the TP53 affected patients), whereas missense TP53 mutation was clearly the most commonly observed type of monoallelic abnormality. It is not easy to explain such a large discrepancy. One possibility is obviously to address the sensitivity of methodologies, especially to consider a more sensitive mutation screening in our study as the result of FASAY.

Although this possibility cannot be excluded, there is another potential explanation. The study by Rossi et al25 was performed on a far more prognostically favorable patient cohort (unmutated IgVH locus in 38% of patients vs 62% in our study) and was done at diagnosis (whereas 52% of our patients were investigated at a later stage of disease). Therefore, it is possible that TP53 missense mutation, which ought to be more harmful because of the resulting p53 activity than cytogenetic deletion,41 is selected later in the course of the disease and is associated with an unfavorable profile of the cohort. In fact, we can also observe the preferential selection of TP53 missense mutation as opposed to deletion through a proportion of affected cells in our study. Although all 3 isolated deletions were detected in only a fraction of the CLL cells (20%, 21%, and 24%), 9 of the 20 single missense mutations progressed to most or rather all CLL cells (≥ 50% of red or pink colonies in FASAY).

Our findings support the view that TP53 missense mutation represents a more severe defect than a deletion in this gene. The same conclusion was derived from a study42 of Li-Fraumeni families, where the missense mutations resulted in tumor onset 9 years earlier than compared with the other TP53 alterations and from the mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome, where the mice harboring the equivalent of human hot-spot mutation R175H were burdened by a greater metastatic potential of tumor cells in comparison with p53wt/− mice.43

Our data concerning the repeated analysis of p53-wt patients during the course of CLL show that this gene is most commonly inactivated by a simultaneous impairment of both alleles. We must emphasize, however, that this selection was very likely to be accelerated by therapy and may not be the same as spontaneous TP53 mutagenesis. This surely occurs in many CLL patients, eg, 32 patients in our study manifested TP53 abnormality, when they have never been treated before. In fact, it is difficult to assign therapy as an unambiguous factor behind the novel mutations. The 2 study groups subjected to repeated investigation, treated and untreated patients, differed significantly from each other simply by the fact that the former required therapy because of a more advanced disease progression. Therefore, the more aggressive biologic behavior of the corresponding tumor cells, ie, faster proliferation or more advanced DNA damage could lead to mutation pressure on the TP53.

All novel mutations occurred in cases with the unmutated IgVH gene, which is associated with shorter telomeres and greater telomerase activity in CLL cells, ie, with their greater proliferation activity.44 In addition, 8 of the 12 patients with novel TP53 defect were treated before investigation I, ie, they manifested unfavorable disease on a long-term basis. In each case, however, the strict association between the newly acquired TP53 defect and the presence of a closely preceding therapy is clear and unquestioned in our study. Theoretically, it is possible that some type of therapy may directly affect the DNA of the TP53 gene, as suggested, eg, for alkylating agents used in CLL.35 The most likely explanation for the observed association is that preexisting undetectable TP53 abnormalities are simply selected in a vacant niche of blood compartments cleared by drug administration; the expansion of the clone would be more rapid under these circumstances than in blood compartments occupied by original CLL cells. This view is also in line with the observation that TP53 mutations appeared in 2 patients treated only with alemtuzumab, an agent with supposedly p53-independent function and no direct effect on DNA damage. In the broadest sense our results support the view that therapeutic intervention in CLL should be performed with maximal caution and only if necessary.37

Our study also provides interesting data concerning the p53 protein activity in cells harboring sole missense mutation. Only a minority (17%) of corresponding samples showed a stabilization of the p53 protein by mutation. This observation is in line with the view that p53 stabilization cannot occur in the presence of the second wt allele.45 Interestingly, the only 2 samples showing the p53 stabilization harbored mutations at frequently mutated codons (Y220C and D281N); the former mutation has been shown to lead to a marked destabilization of the p53 protein,46 and the latter has been associated with the dominant-negative effect over wt allele.47 Although most of missense mutations accompanied by the deletion of the remaining allele led to p53 accumulation (88%), there were some exceptions. Altogether our data show that approaches used for the identification of TP53 mutations through the monitoring of the p53 protein level, ie, immunohistochemistry or western blot, lead to a significant bias in favor of only biallelic defects.

The fact that all tested monoallelic TP53 mutants lost a substantial part of their activity toward the PUMA promoter (in comparison with the wt cells), with only some of them retaining the activity toward BAX or CDKN1A promoters, is interesting. It supports the view that Puma is a critical component of p53-mediated apoptotic response after fludarabine administration.48 The impaired apoptosis in the subgroup of sole TP53 missense mutations, as assessed by viability testing, may then be seen as a consequence of discriminative character in recognition and induction of target genes.49,50

In summary, our study confirms that most of the TP53 defects in CLL result from a virtually simultaneous inactivation of both alleles. However, a significant proportion of affected patients harbor a sole TP53 missense mutation. This abnormality significantly impairs prognosis (requirement for therapeutic intervention) and the survival of CLL patients. It also has a negative impact on a response to DNA damage. We support the view that mutation analysis of the TP53 gene should be included into a prognostic stratification of CLL patients, in addition to common I-FISH screening. For this purpose, FASAY or denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography, both coupled to sequencing, may be considered as the most proper methodologies. They may offer a high rate of analyses and a similar cost-effectiveness. A major benefit of the former is its direct functional readout. FASAY can distinguish partially active (eg, temperature-sensitive) mutations and, because of subcloning, it can also disclose aberrant somatic hypermutations.36 Because FASAY works with RNA, it may not identify some nonsense and frameshift mutations if they lead to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. However, denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography is not able to detect large intragenic deletions. In each case, we recommend performing the mutation analysis before each treatment initiation because novel TP53 defects may be selected by previous therapies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NS9858-4/2008, NR9305-3/2007, and NS10439-3/2009 provided by the Internal Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic and by the Research Proposal MSM0021622430. The work was also supported by the European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC). The work is in line with strategies found within the Czech Leukemia Study Group for Life (CELL).

Authorship

Contributions: J. Malcikova, J.S., L.R., P.K., V.V., S.C., M.S., H.S.F., M.K., and S.P. performed experiments; Y.B., M.D., M.B., and J.Mayer provided samples and clinical data; B.T. performed statistical evaluation; J.S., J. Malcikova, and M.T. designed the study and evaluated results; and M.T. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Martin Trbusek, University Hospital Brno, Department of Internal Medicine–Hematooncology, Jihlavska 20, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic; e-mail: mtrbusek@fnbrno.cz.

References

Author notes

J. Malcikova and J.S. contributed equally to this work