Abstract

Preclinical studies and initial clinical trials have documented the feasibility of adenoassociated virus (AAV)–mediated gene therapy for hemophilia B. In an 8-year study, inhibitor-prone hemophilia B dogs (n = 2) treated with liver-directed AAV2 factor IX (FIX) gene therapy did not have a single bleed requiring FIX replacement, whereas dogs undergoing muscle-directed gene therapy (n = 3) had a bleed frequency similar to untreated FIX-deficient dogs. Coagulation tests (whole blood clotting time [WBCT], activated clotting time [ACT], and activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]) have remained at the upper limits of the normal ranges in the 2 dogs that received liver-directed gene therapy. The FIX activity has remained stable between 4% and 10% in both liver-treated dogs, but is undetectable in the dogs undergoing muscle-directed gene transfer. Integration site analysis by linear amplification–mediated polymerase chain reaction (LAM-PCR) suggested the vector sequences have persisted predominantly in extrachromosomal form. Complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistries, bile acid profile, hepatic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans, and liver biopsy were normal with no evidence for tumor formation. AAV-mediated liver-directed gene therapy corrected the hemophilia phenotype without toxicity or inhibitor development in the inhibitor-prone null mutation dogs for more than 8 years.

Introduction

Hemophilia B is caused by a deficiency in blood coagulation factor IX (FIX). Current treatment consists of intravenous infusion of recombinant or highly purified FIX protein. FIX replacement therapy is effective, but in adult patients is most often used in response to a bleed rather than prophylactically. This approach is less than ideal, because chronic joint disease may develop and there is always a risk of a sudden fatal bleed. Gene therapy could overcome many of the shortcomings of protein replacement therapy if therapeutic levels of FIX were achieved long-term.

Hemophilia B has received intensive investigation as a target disease for gene therapy because1 precise tissue-specific FIX regulation is not necessary,2 murine and canine models of hemophilia B for preclinical investigation are well described, and3 clinical phenotypes correspond to FIX levels, and even a modest increase in FIX activity results in a significant improvement in the severity of the bleeding phenotype.1 Preclinical studies in mice and dogs have clearly demonstrated stable correction of the hemophilic phenotype. Muscle- and liver-directed adenoassociated virus type 2 (AAV2)–mediated FIX gene therapy resulted in stable FIX expression in hemophilia B dogs with a missense mutation, but FIX inhibitors occurred in dogs with a FIX-null mutation after muscle-directed gene therapy.2,3 Liver-directed FIX gene therapy did not result in the development of FIX inhibitors in the FIX-null mutation dogs, except in a case where there was ongoing hepatic inflammation at the time of vector administration (an animal with iron overload and active hepatic fibrosis).4 Initial human clinical trials for AAV-mediated FIX gene therapy were designed based on the successful correction of the hemophilic phenotype in both the murine and canine models.5,6 The open-label, dose-escalation studies demonstrated the vectors to be well-tolerated without significant lasting toxicity.7 The muscle-directed trial failed to demonstrate adequate therapeutic FIX levels, but there was evidence of gene transfer in muscle biopsies in all patients, even up to 3.5 years after vector injection.8,9 Liver-directed FIX expression, initially at therapeutic levels in the highest dose tested, was limited and accompanied by transient transaminitis.10 Based on additional studies, it was hypothesized that a CD8+ T-cell response to an AAV2 capsid protein (that was not seen in the murine and canine studies) limited the duration of expression.10,11 An immune response to the FIX transgene was not detected. Current approaches to AAV-mediated FIX gene therapy will have to be modified using novel AAV serotypes or immune modulation to block the host response to vector and transgene proteins.12-14

Immunologic studies in mice have demonstrated tolerance induction to the transgene product by hepatic gene transfer in adult animals, which was mediated by tolerization of transgene product-specific CD4+ T cells and induction of CD4+ regulatory T cells.15,16 FIX tolerance was also noted after retroviral vector gene transfer in neonatal animals, presumably due to the immature immune system that is prone to develop tolerance.17 Neonatal gene therapy has been remarkably successful not only for FIX deficiency but also factor VIII (FVIII) and the lysosomal storage disease, β-glucuronidase deficiency.18-23 The dramatic success of neonatal gene therapy in animal models with retroviral vectors is tempered by risks associated with insertional mutagenesis and potential differences in maturity of the immune system at birth between humans and animals.24 The murine and canine preclinical studies have clearly demonstrated the efficacy and benefits of FIX gene therapy, while documenting some of the risks to be expected in patients. Most reports have provided follow-up data for 1 year or less, which would be inadequate to screen for late-developing complications such as liver tumors that may not occur until several years after vector administration.25 Multiyear follow-up studies are needed in the canine and primate animal models that have clinical phenotypes, immunologic complications, and life spans adequate for long-term efficacy and safety studies.26

The purpose of this study is to report 8-year follow-up data on FIX-deficient dogs that had previously undergone muscle- or liver-directed AAV2-mediated FIX gene therapy. The results demonstrate long-term (> 8 years) correction of the hemophilia B phenotype after liver-directed FIX gene therapy. FIX administration stimulated an immune response to canine FIX in the hemophilia B dogs that had previously undergone muscle-directed FIX gene therapy, but not in those treated by liver-directed FIX gene therapy. AAV-mediated liver-directed FIX gene therapy is safe and provides long-term correction of canine hemophilia B.

Methods

AAV vector construction and administration

The AAV vectors for muscle- and liver-specific gene therapy were as described.2-4 Briefly, for muscle gene therapy, the vector contained the canine FIX cDNA under transcriptional control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate early (IE) enhancer/promoter, a chimeric β-globin/CMV intron, and the human growth hormone (hGH) poly(A) signal. All dogs received 1012 vg/kg at multiple sites at a single time point. For liver-directed gene therapy, the vector AAV-(ApoE)4/hAAT-cFIX was constructed by replacing the CMV enhancer/promoter with 4 copies of a liver-specific ApoE/hAAT enhancer/promoter combination.2-4,27 The vector was produced by triple transfection of HEK-293 cells using endotoxin-free plasmid DNA and purified by repeated CsCl gradient centrifugation. Titers were determined by quantitative slot blot hybridization. The vector was filter-sterilized. The vector was administered by slow bolus infusion into a mesenteric vein.

Experimental animals

The experimental animals were Lhasa Apso-Basenji cross dogs from the hemophilia B colony housed initially at the Scott-Ritchey Research Center, Auburn University but now at the UAB Medical School. All the treated dogs were males with severe hemophilia B caused by a 5-bp deletion and a C→T transition in the F9 gene that results in an early stop codon and unstable FIX transcript.28 The original experimental cohort included 3 liver-treated, 3 muscle-treated, untreated FIX-deficient, and normal control dogs. Two of the liver-treated, and 2 of the muscle-treated dogs were available for long-term follow-up evaluation. One of the liver-treated dogs (Beech) died 11 weeks after vector administration from a fatal bleed. One of the muscle-treated dogs (Wes) died from a fatal bleed 128 weeks after vector administration. All animals were housed in Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)–accredited facilities, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Auburn University and the University of Alabama.

FIX activity, coagulation, challenge, and Bethesda assays

Blood samples were obtained from hemophilia B dogs as described.3 The whole blood clotting time (WBCT), activated clotting time (ACT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), FIX antigen, FIX activity levels, and Bethesda titer were measured as previously reported.3,4 For the first 6 months of observation, the WBCT tests were terminated after 60 minutes if a clot had not formed; thereafter, the WBCT assay was terminated at 20 minutes if a clot had not formed. The canine FIX protein used for intravenous challenge was a purified, plasma-derived preparation from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Hemophilia B dogs receiving muscle- and liver-directed gene therapy were challenged with 2 intravenous infusions of purified, plasma-derived canine FIX (0.5 mL sterile phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 0.5 mg protein) spaced 4 weeks apart.

Lymphocyte stimulation to purified canine FIX

Five days after a second challenge with purified canine FIX, peripheral blood lymphocytes were isolated from gene therapy treated dogs for lymphocyte proliferation assays. Lymphocytes were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10−6 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and antibiotics for 5 days in the presence of purified canine FIX (10 μg/mL). After this prestimulation period, lymphocytes were rested for 24 hours in the absence of cFIX. Lymphocytes were then restimulated for 48 hours with cFIX, followed by 18 hours of thymidine pulse.29 Lymphocyte proliferation was measured by scintillation counting of 3H-thymidine incorporation in cFIX versus mock-stimulated cells. After challenge, canine-specific enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays were also performed for detection of interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–, interleukin-4 (IL-4)–, or IL-10–secreting cells. For these assays, we used ELISPOT kits for canine IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). As positive controls, recombinant canine IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 were used in these assays. Experimental controls consisted of stimulating each animal's peripheral blood mononuclear cells with 50 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate and 0.5 μg/mL calcium ionomycin to assay for IFN-γ and IL-10 secretion or 4 μg/mL concanavalin A for IL-4 secretion.

DNA and RNA analysis

Total genomic DNA was isolated from canine liver, peripheral blood, and semen using the DNeasy Tissue Kit from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA). Liver tissue was obtained from experimental animals by using a 14-gauge true cut biopsy needle under ultrasound guidance. RNA was isolated from liver biopsies using a RNeasy Micro Kit from Qiagen. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed on total RNA using an oligo-dT primer and a SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). AAV vector-specific normal canine FIX sequences (179-bp amplicon) and a mutant FIX sequences (174-bp amplicon) were detected by PCR using fluorescent-labeled primers spanning the 5-bp mutation followed by fragment analysis using an ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer and ABI GeneMapper version 3.7 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Linear amplification–mediated polymerase chain reaction

In an effort to identify junction sequences between potentially integrated vector genomes and the canine genome, genomic DNA isolated from liver biopsies was analyzed by linear amplification–mediated polymerase chain reaction (LAM-PCR). Biopsies from Brad and Semillon had been obtained 5.5 to 6 years after hepatic gene transfer with AAV2-ApoEhAAT-cF.IX vector (1012 vg/kg). The LAM-PCR analysis was performed by an experienced commercial laboratory GATC Biotech (Konstanz, Germany). Initial extension reactions (linear amplification) were carried out with the following biotinylated primer, which anneals at the hGH poly(A) sequence, KN-831B (5′-AACCACTGCTCCCTTCCCTGTC-3′).

In the next step, double-stranded DNA was generated and cleaved with Tsp509I. Then the linker was ligated to the cleaved DNA. This DNA is used as template for the first exponential PCR using primer KN-831N1 (5′-CTGCTCCCTTCCCTGTCCTTCT-3′) and a primer to the proprietary linker. Because there is no Tsp509I site downstream of the hGH-specific primer in the AAV vector, this strategy should yield junctions at the 3′ end of the vector. The resulting PCR products were used as template for the second PCR with primer KN-831N2 (5′-CCCTTCCCTGTCCTTCTGATTTT-3′) and the linker primer. All 3 primers overlap to a certain extent. Primers KN-831N1 and KN-831N2 serve as nested primers.

Toxicity studies

Canine blood samples were evaluated for white blood cell count (WBC), hematocrit, serum biochemistry (muscle enzyme, liver, and renal function tests) and bile acids tests using standard laboratory assays.30,31 Thoracic and abdominal radiographs, hepatic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and liver biopsy for histopathology and DNA analysis were obtained using standard veterinary clinical techniques. CT of liver was performed with single detector spiral scanner (GE HiSpeed CT/I; General Electric, Milwaukee, WI). While under general anesthesia, the dogs were placed in dorsal recumbency on the CT table. Brief apnea was induced by hyperventilation, and the abdomen was scanned in spiral mode from cranial to the diaphragm to approximately L5. Collimation was 5 mm with pitch of 1. Based on estimated time of arterial enhancement, intravenous contrast medium (RenoCal 76; Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ) was administered by hand injection as a bolus (180 mg iodine/kg body weight), and the scan was repeated during injection. Immediately after this arterial phase scan, the portal phase scan was obtained. Magnetic resonance of the cranial abdomen was performed with a 1.0-T scanner (Picker Vista 1.0T; Picker International, Highland Heights, OH). The dog was positioned in dorsal recumbency and placed in a human head coil. T1 weighted spin echo images (TR 400, TE 8, 5-mm slices, 0 gap, 256 × 256 matrix) and T2 spin echo images (TR 2100-3000, TE 90, 5-mm slices, 0 gap, 256 × 256 matrix) were obtained in transverse and sagittal planes.

Results

Administration of liver-specific AAV2 results in sustained FIX expression

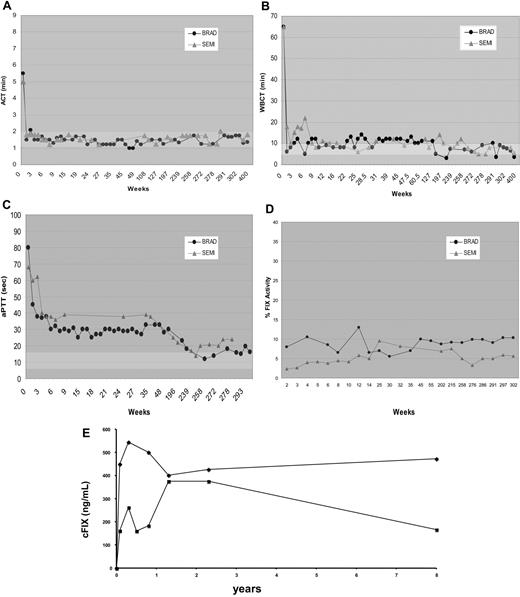

The long-term efficacy and safety of liver-directed AAV-cFIX gene therapy in hemophilia B dogs with a null mutation was assessed. Three animals (Beech, Brad, and Semillon) received liver-specific AAV-cFIX vector delivered into the hepatic circulation via the mesenteric vein.4 Brad and Semillon received a dose of 1.1 × 1012 vg/kg and 1.2 × 1012 vg/kg, respectively, while Beech was injected with an approximately 3× higher dose of 3.4 × 1012 vg/kg AAV-(ApoE)4/hAAT-cFIX. Two of 3 dogs undergoing liver-directed gene therapy had no bleeds for the entire 8-year study period (Table 1). As reported previously, at 11 weeks after vector administration, Beech had a fatal intra-abdominal bleed that was untreatable, due to the presence of high-titer neutralizing anti-FIX antibody. This dog, unlike the other 2 liver-treated dogs, received 3× vector dose but also had concomitant pyruvate kinase deficiency with marked hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. By day 14 after therapy and consistently for the past 8 years, Brad and Semillon have sustained ACT and WBCT values within the normal range (Figure 1). Furthermore, aPTTs have been substantially shortened compared with pretreatment values and remain corrected to near the normal range. The FIX activity has remained stable between 4%-10% in both liver-treated dogs. The FIX antigen levels 7.5 and 8 years after vector administration in Brad and Semillon were 473 and 167 ng/mL, respectively, which is similar to the plasma FIX concentration at the early time points post vector administration (Figure 1).

Summary of hemophilia B dogs undergoing AAV-mediated gene therapy

| Dog . | Age* . | Rx . | Bleed frequency . | Inhibitor status . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kudzu | NA | None | 6/3.6 y | − | Alive/B |

| Brad | 9 mo | Liver | 0/6.25 y | − | Alive/N |

| Semillon | 5.5 mo | Liver | 0/5.9 y | − | Alive/N |

| Beech | 12 mo | Liver | 1/11 wk | + | Dead/FB |

| Sauvignon | 5.5 mo | Muscle | 6/5.9 y | + | Alive/B |

| Wilbur | 8.5 y | Muscle | 8/6.0 y | + | Alive/B |

| Wes | 9 mo | Muscle | 10/2.4 y | + | Dead/FB |

| Dog . | Age* . | Rx . | Bleed frequency . | Inhibitor status . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kudzu | NA | None | 6/3.6 y | − | Alive/B |

| Brad | 9 mo | Liver | 0/6.25 y | − | Alive/N |

| Semillon | 5.5 mo | Liver | 0/5.9 y | − | Alive/N |

| Beech | 12 mo | Liver | 1/11 wk | + | Dead/FB |

| Sauvignon | 5.5 mo | Muscle | 6/5.9 y | + | Alive/B |

| Wilbur | 8.5 y | Muscle | 8/6.0 y | + | Alive/B |

| Wes | 9 mo | Muscle | 10/2.4 y | + | Dead/FB |

NA indicates not applicable; N, normal clotting; B, abnormal clotting; FB, fatal bleed; mo, months; y, years; and wk, weeks.

Age at vector administration.

Coagulation parameters after liver-directed AAV2-mediated FIX gene therapy in hemophilia B dogs. The ACT (A), WBCT (B), aPTT (C), FIX activity levels (D), and FIX antigen concentration (E) as a function of time after AAV2/cFIX vector administration in hemophilia B dogs, Brad (●) and Semillon ( ). Normal ranges of 1 to 2 minutes for ACT, 6 to 10 minutes for WBCT, and 8.0 to 14.4 seconds for aPTT are indicated by the shaded bars.

). Normal ranges of 1 to 2 minutes for ACT, 6 to 10 minutes for WBCT, and 8.0 to 14.4 seconds for aPTT are indicated by the shaded bars.

Coagulation parameters after liver-directed AAV2-mediated FIX gene therapy in hemophilia B dogs. The ACT (A), WBCT (B), aPTT (C), FIX activity levels (D), and FIX antigen concentration (E) as a function of time after AAV2/cFIX vector administration in hemophilia B dogs, Brad (●) and Semillon ( ). Normal ranges of 1 to 2 minutes for ACT, 6 to 10 minutes for WBCT, and 8.0 to 14.4 seconds for aPTT are indicated by the shaded bars.

). Normal ranges of 1 to 2 minutes for ACT, 6 to 10 minutes for WBCT, and 8.0 to 14.4 seconds for aPTT are indicated by the shaded bars.

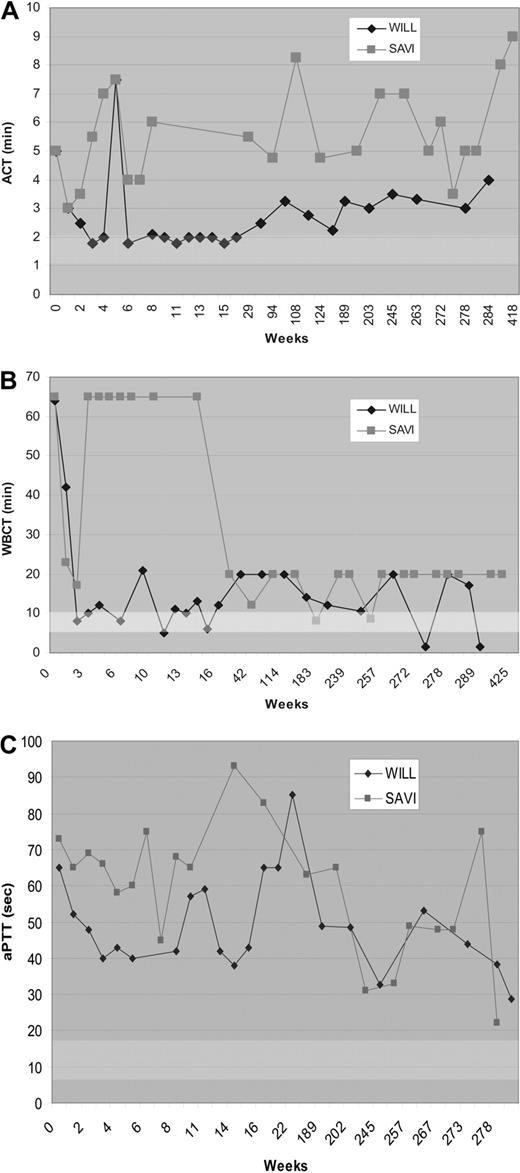

Muscle-directed FIX gene therapy with immune suppression results in partial correction that gradually decreases over time

Three FIX-deficient dogs (Wes, Wilbur, and Sauvignon) were injected with AAV-CMV-cFIX vector at a single time point at multiple intramuscular (IM) sites. The dogs received identical vector doses of 1012 vg/kg. The vector dose/site was 2 × 1012 vg/site for both Wes and Wilbur, whereas Sauvignon received 6.3 × 1011 vg/site. Previous data in a mouse model with a large FIX gene deletion suggested that inhibitor formation after muscle-directed gene therapy could be prevented with transient immune suppression.32 To investigate whether such a strategy would be successful in the outbred canine model with a high risk of inhibitor formation, one dog, Wilbur, was treated with the immunosuppressive drug cyclophosphamide (Cy) in conjunction with AAV-FIX treatment. Wilbur received Cy on the day of vector administration and biweekly afterward through week 6. As reported earlier, Wes and Sauvignon initially showed transient correction of WBCT during the first week after vector administration, but developed inhibitory antibodies by day 9 and day 14, respectively.3 Wes maintained an elevated anti-cFIX titer before he succumbed to a fatal bleed at week 128 after treatment. From week 2 throughout the 8-year study period, Sauvignon has demonstrated prolonged aPTT, ACT, and WBCT in addition to a persistent Bethesda titer and decreased FIX activity (Figure 2). The plasma FIX antigen was still undetectable (0 ng/mL) 8 years after vector administration in Sauvignon. In Wilbur, muscle-directed FIX gene therapy with transient immune suppression resulted in substantial shortening of ACT and WBCT and partial correction of the aPTT coagulation time that was stable for 7 months. However, these improved coagulation parameters gradually returned to pretreatment levels over the next 6 months (Figure 2). Wilbur has had a recurring evanescent Bethesda titer during the 8-year study period. Hemophilia B dogs (n = 3) receiving IM injections of AAV-FIX with or without immune suppression at the time of vector administration had bleed frequencies similar to untreated FIX-deficient dogs.

Coagulation parameters after muscle-directed AAV2-mediated FIX gene therapy in hemophilia B dogs. The ACT (A), WBCT (B), and aPTT (C) as a function of time after vector administration in hemophilia B dogs, Wilbur (♦) and Sauvignon ( ). The arrows indicate cyclophosphamide administration to Wilbur before and 2, 4, and 6 weeks after vector administration. The WBCT test was terminated at 60 minutes if a clot had not formed for the first 15 weeks. After 15 weeks, the WBCT test was terminated after 20 minutes if a clot had not formed.

). The arrows indicate cyclophosphamide administration to Wilbur before and 2, 4, and 6 weeks after vector administration. The WBCT test was terminated at 60 minutes if a clot had not formed for the first 15 weeks. After 15 weeks, the WBCT test was terminated after 20 minutes if a clot had not formed.

Coagulation parameters after muscle-directed AAV2-mediated FIX gene therapy in hemophilia B dogs. The ACT (A), WBCT (B), and aPTT (C) as a function of time after vector administration in hemophilia B dogs, Wilbur (♦) and Sauvignon ( ). The arrows indicate cyclophosphamide administration to Wilbur before and 2, 4, and 6 weeks after vector administration. The WBCT test was terminated at 60 minutes if a clot had not formed for the first 15 weeks. After 15 weeks, the WBCT test was terminated after 20 minutes if a clot had not formed.

). The arrows indicate cyclophosphamide administration to Wilbur before and 2, 4, and 6 weeks after vector administration. The WBCT test was terminated at 60 minutes if a clot had not formed for the first 15 weeks. After 15 weeks, the WBCT test was terminated after 20 minutes if a clot had not formed.

Long-term persistence and expression of vector DNA after liver-directed gene transfer

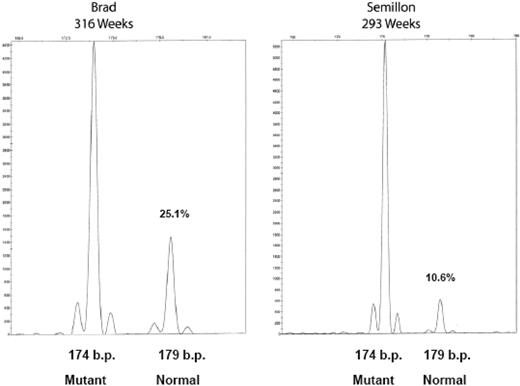

Tissues were harvested for the detection of vector and transgene expression from liver, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and semen. A PCR assay was used that distinguishes mutant from wild-type canine FIX sequences. In this assay, normal FIX amplicon (derived from the transgene) is 179 bp, while products derived from mutant sequence are 174 bp. Evaluation of liver biopsies from the 2 liver-directed gene therapy dogs demonstrated persistence of vector FIX DNA for more than 6 years in both dogs (Figure 3). Consistent with our earlier findings on hepatic AAV-2 gene transfer in mice and dogs, vector sequences were present at a copy number of approximately 0.1 to 0.3 copies per diploid genome. Consistent with an approximately 2-fold difference in transgene expression, Brad had an approximately 2.5-fold higher gene copy number. Vector FIX DNA was undetectable in WBC and sperm DNA (data not shown). At the 6-year time point, liver biopsies were also evaluated for expression of vector-derived FIX mRNA. Normal vector-derived canine FIX RNA is clearly detectable in liver biopsies from both liver-treated dogs (Figure 4). The normal FIX mRNA levels were higher than expected from the low gene copy number. While mRNA levels of the vector-derived wild-type cFIX transcript were approximately 40% of endogenous unstable mRNA, mRNA levels in transduced hepatocytes may be even higher (probably approximately 1 log higher than endogenous message) since only a few hepatocytes express FIX.

Vector persistence in hemophilia B dogs after liver-directed gene therapy. Hepatic biopsies, DNA isolation, FIX PCR, and microcapillary electrophoresis were as described. The fragment at 174 bp is the endogenous mutant FIX amplicon, and the fragment at 179 bp is the AAV vector-derived normal canine FIX amplicon. The relative percentage of each fragment is indicated (%) to the right of each peak. Amplification of DNA from peripheral blood and sperm DNA generated only the 174-bp fragment (not shown).

Vector persistence in hemophilia B dogs after liver-directed gene therapy. Hepatic biopsies, DNA isolation, FIX PCR, and microcapillary electrophoresis were as described. The fragment at 174 bp is the endogenous mutant FIX amplicon, and the fragment at 179 bp is the AAV vector-derived normal canine FIX amplicon. The relative percentage of each fragment is indicated (%) to the right of each peak. Amplification of DNA from peripheral blood and sperm DNA generated only the 174-bp fragment (not shown).

Accumulation of vector-derived normal FIX mRNA in hemophilia B dogs, Brad and Semillon, after liver-directed gene therapy. Hepatic biopsies, RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, PCR, and microcapillary electrophoresis were as described.

Accumulation of vector-derived normal FIX mRNA in hemophilia B dogs, Brad and Semillon, after liver-directed gene therapy. Hepatic biopsies, RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, PCR, and microcapillary electrophoresis were as described.

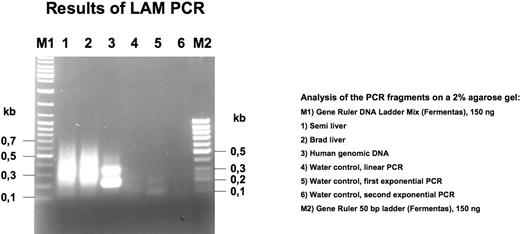

Integration site analysis

The results of the LAM-PCR are shown in Figure 5. Human genomic DNA was used as a positive control. No distinct bands were obtained with the liver DNA from either Brad or Semillon as a template, suggesting that there was not a prevalent clone of integrated vector. PCR fragments were cloned in Escherchia coli (Topo cloning). A total of 32 clones were randomly chosen for sequencing with M13 primer, and 28 of these had an insert. Sequences were analyzed with Lasergene software and identified by BLAST database searches (Table 2). All junctions appear to represent recombination events between vector sequences (note that AAV vector genomes upon transduction circularize and/or form head-to-head and head-to-tail concatemers) and in most cases retained approximately 120 bp of the inverted terminal repeat (ITR) sequence. For each sample, several additional clones (11-12 per sample) yielded inserts of 1 to 175 bp with sequences that could not be identified by BLAST search or comparison with vector sequences and therefore could not be conclusively interpreted. No evidence for integration in the canine genome was found.

LAM-PCR analysis of liver biopsy DNA from Brad and Semillon. Note absence of unique bands in samples from Brad and Semillon.

LAM-PCR analysis of liver biopsy DNA from Brad and Semillon. Note absence of unique bands in samples from Brad and Semillon.

Summary of the LAM-PCR sequencing results

| Liver sample . | Sequence . | Junction . |

|---|---|---|

| Brad | Human α1-antitrypsin promoter region (118 bp) | 5′ end of transcription start as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (64 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | Human β-globin (34 bp) | Exon/intron splice junction as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (64 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (143 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (105 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (153 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | AAV vector (43 bp) | Part of expression cassette |

| Brad | ApoE enhancer (135 bp) | Enhancer used in expression cassette |

| Brad | AAV vector (42 bp) | Cloning sites |

| Brad | AAV vector (40 bp) | Cloning sites |

| Brad | hGH poly(A) (131 bp) | Poly(A) used in AAV vector cassette |

| Semillon | AAV vector (222 bp) | hGH poly(A) used in AAV vector cassette |

| Semillon | Canine FIX cDNA (98 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Semillon | AAV vector (47 bp) | Cloning sites |

| Semillon | hGH poly(A) (177 bp) | Poly(A) used in AAV vector cassette |

| Semillon | Canine FIX cDNA (144 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Semillon | Canine FIX cDNA (143 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Semillon | hGH poly(A) (121 bp) | Poly(A) used in AAV vector cassette |

| Semillon | Canine FIX cDNA (32 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Semillon | Plasmid DNA (106 bp) | (Packaging of helper plasmid DNA or cloning artifact) |

| Liver sample . | Sequence . | Junction . |

|---|---|---|

| Brad | Human α1-antitrypsin promoter region (118 bp) | 5′ end of transcription start as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (64 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | Human β-globin (34 bp) | Exon/intron splice junction as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (64 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (143 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (105 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | Canine FIX cDNA (153 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Brad | AAV vector (43 bp) | Part of expression cassette |

| Brad | ApoE enhancer (135 bp) | Enhancer used in expression cassette |

| Brad | AAV vector (42 bp) | Cloning sites |

| Brad | AAV vector (40 bp) | Cloning sites |

| Brad | hGH poly(A) (131 bp) | Poly(A) used in AAV vector cassette |

| Semillon | AAV vector (222 bp) | hGH poly(A) used in AAV vector cassette |

| Semillon | Canine FIX cDNA (98 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Semillon | AAV vector (47 bp) | Cloning sites |

| Semillon | hGH poly(A) (177 bp) | Poly(A) used in AAV vector cassette |

| Semillon | Canine FIX cDNA (144 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Semillon | Canine FIX cDNA (143 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Semillon | hGH poly(A) (121 bp) | Poly(A) used in AAV vector cassette |

| Semillon | Canine FIX cDNA (32 bp) | 3′-untranslated region as present in vector |

| Semillon | Plasmid DNA (106 bp) | (Packaging of helper plasmid DNA or cloning artifact) |

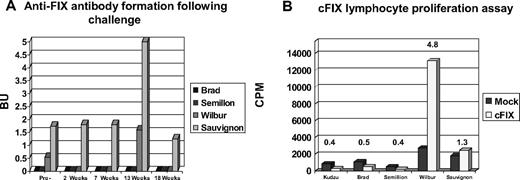

FIX challenge

Hemophilia B dogs receiving muscle- and liver-directed gene therapy were challenged with 2 intravenous infusions of purified, plasma-derived canine FIX (0.5 mL sterile PBS containing 0.5 mg protein) spaced 4 weeks apart, 6 years after vector administration. Previous results from this colony of hemophilic dogs have demonstrated that an inhibitory antibody against canine FIX is apparent by day 9 after infusion of a single dose of purified canine FIX.3 Upon challenge with FIX, liver-directed AAV-FIX dogs (Brad and Semillion) did not form anti–canine FIX antibodies (Figure 6). Other serum chemistries such as liver enzymes also remained in the normal range. After challenge, an in vitro lymphocyte proliferation assay was performed. Lymphocytes from both liver-directed gene therapy dogs were unresponsive to cFIX (stimulation index < 1). In the lymphocyte proliferation assay, Sauvignon and Wilbur, the 2 dogs receiving muscle-directed gene transfer, had stimulation indexes of 1.35 and 4.75, respectively. After challenge, these dogs also showed a modest (2-fold) increase in Bethesda titers. Intravenous protein infusion may lead to lymphocyte activation in the spleen.33 However, due to concerns related to risks associated with the biopsy procedure in hemophilic animals, splenic biopsies were not performed. Using canine-specific ELISPOT assays, peripheral blood lymphocytes from muscle- and liver-directed gene therapy dogs were tested for detection of IFN-γ–, IL-4–, or IL-10–secreting cells. When cells were stimulated with purified canine FIX (1-10 μg/mL) these assays failed to detect cytokine production above background levels. Cytokine production in response to nonspecific stimuli was similar with peripheral blood lymphocytes from experimental and normal dogs.

Bethesda assay/lymphocyte proliferation after FIX challenge. Hemophilia B dogs receiving muscle- or liver-directed AAV-mediated gene therapy were challenged with 2 infusions of cFIX. After challenge, Bethesda assays (A) and lymphocyte proliferation assays (B) were performed.

Bethesda assay/lymphocyte proliferation after FIX challenge. Hemophilia B dogs receiving muscle- or liver-directed AAV-mediated gene therapy were challenged with 2 infusions of cFIX. After challenge, Bethesda assays (A) and lymphocyte proliferation assays (B) were performed.

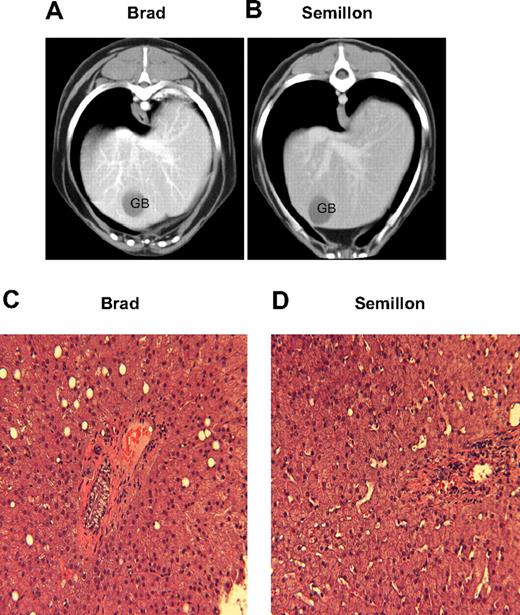

Lack of liver and muscle pathology associated with AAV2-mediated gene therapy

Hematologic parameters and serum chemistry profiles including liver and muscle enzymes periodically monitored throughout the study period were within normal limits. A representative dataset from 5.5 to 6 years after vector administration is illustrated in Table 3. None of the animals receiving IM- or liver-directed AAV-cFIX administration had elevations of muscle or liver enzyme levels above the normal range over the 6-year period. Hepatic CT showed the livers in all dogs were of uniform opacity, and no abnormal areas of hyperattenuation or hypoattenuation were found on pre- or postcontrast images. In addition, MRI showed that the liver parenchyma in all dogs had uniform signal intensity with no evidence of tumor formation (not shown). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of liver biopsies showed an overall normal hepatic architecture with centrilobular and midzonal hepatocellular hypertrophy without inflammation, necrosis, or fibrosis (Figure 7).

Clinical pathology data in hemophilia B dogs after AAV-mediated FIX gene therapy

| Dog . | WBC, ×103/μL . | Hct, % . | Platelet, ×103/μL . | ALT, U/L . | ALP, U/L . | BUN, mg/dL . | Cr, mg/dL . | Alb, g/dL . | T. bili. mg/dL . | Bile acids, μmol/L . | CK, U/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kudzu | 14.6 | 49.3 | 438 | 76 | 28 | 12.1 | 1.0 | 3.5 | < 0.1 | 2.2 | 94 |

| Brad | 11.0 | 48.7 | 636 | 105 | 99 | 13.7 | 0.9 | 4.0 | < 0.1 | 2.8 | 169 |

| Semillon | 9.8 | 45.6 | 648 | 38 | 436 | 9.9 | 0.9 | 3.3 | < 0.1 | 1.9 | 103 |

| Wilbur | 14.9 | 70.6 | 595 | 87 | 554 | 28.9 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 0.2 | ND | 106 |

| Sauvignon | 13.7 | 45.5 | 737 | 44 | 66 | 10.6 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 9.4 | 242 |

| Normal range | 6.0-17.0 | 37.0 -55.0 | 164-510 | 26-200 | 3.5-95 | 10-25 | 0.0-1.3 | 2.6-3.5 | 0.1-0.3 | 0.1-6.5 | 92-357 |

| Dog . | WBC, ×103/μL . | Hct, % . | Platelet, ×103/μL . | ALT, U/L . | ALP, U/L . | BUN, mg/dL . | Cr, mg/dL . | Alb, g/dL . | T. bili. mg/dL . | Bile acids, μmol/L . | CK, U/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kudzu | 14.6 | 49.3 | 438 | 76 | 28 | 12.1 | 1.0 | 3.5 | < 0.1 | 2.2 | 94 |

| Brad | 11.0 | 48.7 | 636 | 105 | 99 | 13.7 | 0.9 | 4.0 | < 0.1 | 2.8 | 169 |

| Semillon | 9.8 | 45.6 | 648 | 38 | 436 | 9.9 | 0.9 | 3.3 | < 0.1 | 1.9 | 103 |

| Wilbur | 14.9 | 70.6 | 595 | 87 | 554 | 28.9 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 0.2 | ND | 106 |

| Sauvignon | 13.7 | 45.5 | 737 | 44 | 66 | 10.6 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 9.4 | 242 |

| Normal range | 6.0-17.0 | 37.0 -55.0 | 164-510 | 26-200 | 3.5-95 | 10-25 | 0.0-1.3 | 2.6-3.5 | 0.1-0.3 | 0.1-6.5 | 92-357 |

Blood samples were obtained 5.5-6 years after vector administration. Hct indicates hematocrit; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; Alb, albumin; T. bili, total bilirubin; CK, creatine kinase; and ND, not done.

CT and histopathologic evaluation of hemophilia B dogs after liver-directed AAV gene therapy. After contrast sagittal CT sections of hemophilia B dog Brad (A) and hemophilia B dog Semillon (B) livers. H&E sections (×200) of liver biopsy obtained 6 years after vector administration in Brad (C) and Semillon (D). The CT evaluation, liver biopsy, and histologic processing were as described. GB indicates gall bladder.

CT and histopathologic evaluation of hemophilia B dogs after liver-directed AAV gene therapy. After contrast sagittal CT sections of hemophilia B dog Brad (A) and hemophilia B dog Semillon (B) livers. H&E sections (×200) of liver biopsy obtained 6 years after vector administration in Brad (C) and Semillon (D). The CT evaluation, liver biopsy, and histologic processing were as described. GB indicates gall bladder.

Discussion

The FIX-deficient dogs in the current study have a complex deletion mutation (null mutation) that results in mRNA instability and complete absence of FIX activity. These dogs are at high risk for inhibitor formation due to complete lack of FIX synthesis. Infusion of purified cFIX and IM administration of AAV cFIX vectors stimulates rapid production of inhibitors in these dogs; for this reason, human subjects with null mutations were excluded in the clinical study of IM administration of AAV-FIX. In contrast, in the FIX-deficient dogs with a missense mutation, IM administration of an AAV vector expressing cFIX results in stable FIX expression. Therefore the UAB hemophilia B dogs are a good model for those hemophilia B patients at risk for inhibitor formation. Surprisingly, we found liver-directed AAV-mediated FIX gene therapy resulted in stable FIX expression for at least 1 year in 2 of these dogs.4 However, 1 of the liver-treated dogs (Beech) died of a fatal bleed 11 weeks after vector administration. This dog also had concurrent pyruvate kinase deficiency with moderate hepatic inflammation and developed high-titer anti-FIX and anti-AAV2 antibodies. This dog received a dose of vector 3 times higher than the other 2 dogs, so it is not clear whether the immune response was due to concurrent hepatic inflammation or increased vector dose. An 8-year follow-up study of the hemophilia B dogs that previously underwent liver- or muscle-directed AAV-mediated FIX gene therapy is described in the current report.

The 2 hemophilia B dogs that had previously undergone liver-directed FIX gene therapy have remained clinically normal without a single bleeding episode in 8 years, while the 2 remaining dogs that underwent muscle gene transfer have continued to have a bleeding frequency comparable with untreated FIX-deficient dogs. The FIX activity and antigen levels have persisted between 4% and 10% of normal FIX levels in both dogs that underwent liver-directed gene therapy. The aPTT, WBCT, and ACT have paralleled the percentage FIX activity, remaining at the upper limits of the normal range and significantly improved compared with untreated dogs. In contrast, the coagulation parameters returned to pretreatment values within weeks of vector administration in the hemophilia B dogs that underwent muscle-directed FIX gene therapy. The coagulation parameters in the hemophilia B dog administered cyclophosphamide in the peritreatment period improved for a prolonged period (6 months) but also gradually returned to the pretreatment range. This dog has continued to have bleeding episodes similar to the pretreatment bleed frequency. These findings clearly demonstrate stable long-term (> 8 years) correction of the hemophilic phenotype in inhibitor prone dogs with AAV-mediated liver-directed FIX gene therapy.

Previously, we demonstrated that IV administration of highly purified cFIX results in an immune response and the development of FIX inhibitors in the null mutation dogs.3 Therefore, we administered cFIX to the hemophilia B dogs that had undergone liver- or muscle-directed gene therapy to determine whether these dogs exhibited tolerance to FIX challenge. Neither of the liver-directed gene therapy dogs developed FIX inhibitors or demonstrated alloreactivity in a FIX-dependent lymphocyte proliferation assay. On the other hand, the muscle-directed gene therapy dogs had an increase in the Bethesda titer and/or showed FIX-dependent lymphocyte proliferation. The dog that had previously undergone muscle-based gene therapy with cyclophosphamide immunosuppression had a significant response to cFIX in a lymphocyte proliferation assay. Initial immune suppression in Wilbur did not prevent activation of cFIX-specific T cells at late time points. This may in part be due to declining levels of cFIX expression, inadequate to maintain tolerance. In addition, muscle transduction is not as ideal for tolerance induction as liver.34 These results are consistent with immunologic studies in hemophilia B mice, which suggest liver-directed gene therapy induces FIX tolerance by incompletely understood mechanisms.15,35-37

Evaluation of liver biopsies from the 2 liver-directed gene therapy dogs demonstrated persistence of vector FIX DNA for more than 6 years in both dogs. The vector FIX gene copy number roughly paralleled the blood FIX activity. The vector FIX mRNA abundance was increased above that expected from the vector DNA copy number suggesting that the normal FIX mRNA preferentially accumulates compared with the endogenous mutant FIX mRNA. This is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that the complex deletion mutation in the UAB hemophilia B dogs causes premature termination, FIX mRNA instability, and a complete absence of FIX protein.28 However, exact correlation of vector copy number and FIX activity is difficult, because of uneven vector distribution in the liver.38

In mice, it has been demonstrated that AAV2 vectors integrate in vivo in the liver at low frequency (approximately 5% of transduced hepatocytes, approximately 1:400 hepatocytes assuming transduction of approximately 5% of total hepatocytes).39-42 These investigations took advantage either of a shuttle vector, which harbors a bacterial origin of replication and an ampicillin resistance gene for rescue in E coli, or by using an in vivo selection system for proliferation of hepatocytes with stable integrants.39-42 Because in the quiescent liver tissue (ie, in the absence of clonal expansion or tumor formation), only one or few cells with integrated vector result from a single integration event, it would be extraordinarily difficult to clone out junction fragments unless the above-mentioned model systems are applied. Nevertheless, we attempted to obtain such integration junctions between the AAV-canine FIX vector and hepatic DNA isolated from biopsies from 2 of the hemophilia B dogs. LAM-PCR has emerged as the “gold standard” for analysis of integration junctions in clinical trials that rely on integrating vector systems such as retroviral vectors (note, however, that these vectors, in contrast to AAV, do not form episomal circles/concatemers, and that typically clones of cells derived from hematopoietic stem cells, progenitor cells, or tumor tissue are being analyzed).43 Integration site analysis by LAM-PCR on liver biopsy samples obtained 5.5 to 6 years after vector administration failed to detect vector integration to chromosomal DNA. The recovery of vector-vector chromosomal DNA junctions and the absence of vector-chromosomal DNA junctions suggest extrachromosomal persistence, which is an obvious safety advantage over integrating vectors due to the low likelihood of insertional mutagenesis.

There is tremendous concern regarding the safety of gene therapy after the death of a patient in an adenoviral vector-based gene therapy trial for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, a second patient in an AAV vector-based rheumatoid arthritis trial, and the development of vector-induced leukemias in 5 patients in trials for X-linked severe-combined immunodeficiency (SCID). The adverse events were initially observed approximately 3 years after ex vivo gene therapy in the X-linked SCID trial. Previous studies in mice noted liver tumor formation after AAV vector administration.25,44,45 In these studies, malignancy after AAV gene therapy was thought to occur due to expression of certain transgenes, vector transgene cooperation,44 or AAV vector integration.45 These unfortunate findings point to the need for long-term safety and efficacy studies in the large animal models with life spans and immune responses similar to humans. There was no evidence of vector integration or tumor formation in any of the dogs during the 8-year follow-up period, which is more than half the life span of most dogs. This is significant, because the current hemophilia B gene therapy trials are only enrolling adult patients. The present study clearly demonstrates not only the efficacy but also the safety of AAV-mediated gene therapy, for at least 8 years in dogs.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Scott-Ritchey Research Center (Auburn, AL; G.P.N. and C.D.L.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant nos. R24 HL086944 (C.D.L. and G.P.N.), R01 AI/HL51390 (R.W.H.), and NIH/NHLBI 2P01 HL64190 (K.A.H. and V.R.A.), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (K.A.H.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: G.P.N. performed and analyzed research and wrote the paper; R.W.H. and C.D.L. designed, performed, and analyzed research and wrote the paper; J.D.M., V.A.A., D.M.T., and J.T.H. performed research; F.W.G. performed and analyzed research; and K.A.H. designed and analyzed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.W.H. is receiving royalties from Genzyme for AAV-mediated FIX gene therapy. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Clinton D. Lothrop Jr, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, School of Medicine, University of Alabama-Birmingham, 404 MCLM Bldg, 1918 University Avenue, Birmingham, AL 35294; e-mail: clothrop@uab.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal