Abstract

The activity of allogeneic CD8+ T cells specific for leukemia-associated antigens (LAAs) is thought to mediate, at least in part, the curative effects of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in myeloid malignancies. However, the identity and nature of clinically relevant LAA-specific CD8+ T-cell populations have proven difficult to define. Here, we used a combination of coreceptor-mutated peptide-major histocompatibility complex class I (pMHCI) tetramers and polychromatic flow cytometry to examine the avidity profiles, phenotypic characteristics, and anatomical distribution of HLA A*0201-restricted CD8+ T-cell populations specific for LAAs that are over-expressed in myeloid leukemias. Remarkably, LAA-specific CD8+ T-cell populations, regardless of fine specificity, were confined almost exclusively to the bone marrow; in contrast, CD8+ T-cell populations specific for the HLA A*0201-restricted cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp65495-503 epitope were phenotypically distinct and evenly distributed between bone marrow and peripheral blood. Furthermore, bone marrow-resident LAA-specific CD8+ T cells frequently engaged cognate antigen with high avidity; notably, this was the case in all tested bone marrow samples derived from patients who achieved clinical remission after HSCT. These data suggest that concomitant examination of bone marrow specimens in patients with myeloid leukemias might yield more definitive information in the search for immunologic prognosticators of clinical outcome.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) can be curative in a large proportion of patients with myeloid malignancies and there is substantial evidence to support the notion that this is mediated, at least to some extent, by a graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect.1 However, the precise identity of the allogeneic leukemia-reactive T cells that are responsible for the GVL effect remains obscure. It is established that certain proteins are over-expressed in leukemic states. Peptides derived from these proteins can be displayed at high densities bound to major histocompatibility complex class I (MHCI) molecules on the cell surface and act as leukemia-associated antigens (LAAs) for immune recognition.2 Two such well-studied LAAs that are known to elicit human leukocyte antigen (HLA) A*0201-restricted CD8+ T-cell responses are the PR3169-177/HNE168-176 (PR1) and WT1126-134 epitopes derived from proteinase 3/human neutrophil elastase and Wilms tumor antigen-1, respectively.3-8 The selective recognition and elimination of leukemic but not healthy hematopoietic progenitor cells by CD8+ T cells specific for PR1 and WT1126-134 indicates that these LAAs might be useful target antigens for immunotherapeutic interventions. However, it remains unclear to what extent such LAA-specific CD8+ T-cell responses mediate protective effects in vivo before and after HSCT.9 In part, this reflects limitations of current technological approaches to the detection of low frequency antigen-specific CD8+ T cells directly ex vivo; furthermore, for reasons of feasibility, the majority of studies to date have been restricted to analyses of samples derived from peripheral blood.

In the present study, we used coreceptor-mutated peptide-MHCI (pMHCI) tetrameric complexes to detect, enumerate and characterize LAA-specific CD8+ T cells according to their phenotypic properties and avidity for antigen at distinct anatomical sites in patients with myeloid malignancies. The data indicate that evaluation of bone marrow specimens with high resolution immunotechnological approaches might contribute to our understanding of CD8+ T cell–mediated antileukemic effects.

Methods

Samples

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) were collected from patients with myeloid malignancies (acute myeloid leukemia, AML; chronic myeloid leuemia, CML) before and after HSCT under institutional review board–approved protocols at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Cells were purified by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved according to standard procedures, then thawed and rested for a minimum of 2 hours at 37°C/5% CO2 in Iscove Modified Dulbecco Medium (IMDM; Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Gemini Bio-Product, Woodland, CA), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) before staining with tetrameric pMHCI complexes.

Tetrameric pMHCI complexes

The double α3 domain D227K/T228A mutation and the single α2 domain Q115E mutation in the HLA A*0201 heavy chain have been described previously; these mutations abrogate and enhance CD8 binding, respectively, without affecting the fidelity of T-cell receptor (TCR) binding.10-12 Tetrameric D227K/T228A pHLA A*0201 complexes selectively identify high avidity cognate CD8+ T cells13-15 ; in contrast, Q115E pHLA A*0201 tetramers enable the inclusive identification of low avidity cognate CD8+ T cells.16 Biotinylated monomeric D227K/T228A, wildtype (WT) and Q115E pHLA A*0201 complexes were produced for the following epitopes: (1) CMV pp65495-503 (NLVPMVATV)17 ; (2) WT1126-134 (RMFPNAPYL)5 ; and (3) PR3169-177/HNE168-176 (PR1; VLQELNVTV).3,6 All tetramers were prepared afresh from cryopreserved monomers to eliminate potential bias arising from differential protein stability.18 In all experiments, concentration and volume were standardized for each pHLA A*0201 tetramer preparation to enable direct comparisons limited solely to differences in CD8 binding properties.

Monoclonal antibodies

The following fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were purchased from commercial vendors: (1) αCD3-cyanin-7-allophycocyanin (Cy7APC), αCD3-Cy7-phycoerytherin (Cy7PE), αIFNγ-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), αMIP-1β-PE, αTNFα-Cy7PE, and αIL-2-APC (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA); (2) αCD4-Cy5.5PE, αCD4-Pacific Blue, αCD8-Cy7APC, αCD8-Pacific Orange, αCD14-Pacific Blue, αCD19-Pacific Blue, and αCD57-FITC (Caltag/Invitrogen, Burlingame, CA); and (3) αCD27-Cy5PE, αCD45RO-PE, and αCD45RO-Texas Red-PE (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). In addition, for some experiments, mAbs were conjugated in-house: (1) αCD33 and αCD34 (BD Biosciences) were conjugated to Pacific Blue (Invitrogen); and (2) αCD4, αCD8, αCD45RA, and αCD57 (BD Biosciences) were conjugated to quantum dot (QD) 655, QD585, QD705, and QD545 (Invitrogen), respectively. The fixable amine reactive dye ViViD (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to eliminate dead cells from the analysis.19

Flow cytometry

pMHCI tetramer staining and phenotypic analysis.

Thawed PBMCs and BMMCs (1-2 × 106 per experimental condition) were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with ViViD (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) for 15 minutes at room temperature. After a further wash, the cells were stained with pre-titered pHLA A*0201 tetramers as described previously,20 washed with FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum and 0.05% sodium azide) and stained with surface marker-specific mAbs for 15 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then washed again with FACS buffer, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Tousimis, Rockville, MD) for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed 1 further time and resuspended in 200 μl FACS buffer before acquisition using either a modified LSR II or a Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). A minimum of 2 × 105 events was collected for each condition. Compensation for spectral overlap was performed electronically using individually stained Igκ antibody capture beads (BD Biosciences) representing each fluorochrome in the experimental panel. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, San Carlos, CA). The gating strategy is illustrated in Figure 1. Forward scatter–area versus forward scatter–height properties were used to exclude cell aggregates; live T cells were then separated from dead cells, monocytes and B cells using a ViViD/CD14/CD19 (dump channel) versus CD3 bivariate plot. In some experiments, αCD33 and αCD34 mAbs conjugated to Pacific Blue were also included in the dump channel to exclude immature and mature myeloid cells from the analysis. Lymphocytes were then identified in a forward scatter–area versus side scatter–area plot after exclusion of fluorochrome aggregates before analysis of tetramer binding and phenotypic characteristics within the CD8+ T-cell population. Gating was standardized within individual samples to arrive at a fully comparative dataset; furthermore, data were analyzed independently by 2 observers to ensure consistency. The Pestle and Spice software suite (Mario Roederer, NIH) was used for graphing and statistical analysis of phenotypic data. In bar charts, differences between groups were determined statistically with Student t test; in pie charts, significance was tested by comparing pies over 1000 rounds using permutation analysis.

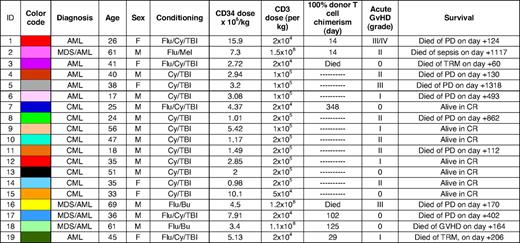

Gating scheme and representative flow cytometric data showing the identification of CD8+ T-cell populations specific for CMV pp65495-503 and PR1 in peripheral blood and bone marrow of a patient with CML pre-HSCT. (A) The forward scatter-area (FSC-A) versus forward scatter-height (FSC-H) profile was used to exclude cell aggregates and large cells from the analysis; live T cells were discriminated from dead cells, monocytes and B cells in a CD3 versus ViViD/CD14/CD19 bivariate plot. Next, fluorochrome aggregates were gated out and small lymphocytes were identified in a FSC-A versus side scatter-area (SSC-A) plot. Antigen-specific cells were then identified in a CD8 versus pHLA A*0201 tetramer plot. Gating of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells was performed after background assessment, which differs according to the coreceptor binding properties of each pHLA A*0201 tetrameric form as described previously.11,16,43 Individual plots were examined visually by 2 independent observers; only consistent interpretations were included for further analysis. (B) Representative data showing the identification of PR1-specific (left columns) and CMV-specific (right columns) CD8+ T-cell populations in the peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) of a patient with CML pre-HSCT (patient 13; Table 1). Cognate D227K/T228A, WT and Q115E pHLA A*0201 tetramers were used in 3 separate and parallel analyses for each antigen specificity; drawn gates identify only distinct populations of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells for clarity. In the example shown, PR1-specific CD8+ T cells preferentially localized to the bone marrow and bound cognate antigen with high avidity; in contrast, CMV-specific CD8+ T cells were evenly distributed between the bone marrow and peripheral blood compartments and, atypically, did not bind cognate antigen with high avidity. Differential staining intensities between antigen specificities likely reflect avidity ranges that lie within the capture window for each pHLA A*0201 tetrameric form.

Gating scheme and representative flow cytometric data showing the identification of CD8+ T-cell populations specific for CMV pp65495-503 and PR1 in peripheral blood and bone marrow of a patient with CML pre-HSCT. (A) The forward scatter-area (FSC-A) versus forward scatter-height (FSC-H) profile was used to exclude cell aggregates and large cells from the analysis; live T cells were discriminated from dead cells, monocytes and B cells in a CD3 versus ViViD/CD14/CD19 bivariate plot. Next, fluorochrome aggregates were gated out and small lymphocytes were identified in a FSC-A versus side scatter-area (SSC-A) plot. Antigen-specific cells were then identified in a CD8 versus pHLA A*0201 tetramer plot. Gating of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells was performed after background assessment, which differs according to the coreceptor binding properties of each pHLA A*0201 tetrameric form as described previously.11,16,43 Individual plots were examined visually by 2 independent observers; only consistent interpretations were included for further analysis. (B) Representative data showing the identification of PR1-specific (left columns) and CMV-specific (right columns) CD8+ T-cell populations in the peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) of a patient with CML pre-HSCT (patient 13; Table 1). Cognate D227K/T228A, WT and Q115E pHLA A*0201 tetramers were used in 3 separate and parallel analyses for each antigen specificity; drawn gates identify only distinct populations of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells for clarity. In the example shown, PR1-specific CD8+ T cells preferentially localized to the bone marrow and bound cognate antigen with high avidity; in contrast, CMV-specific CD8+ T cells were evenly distributed between the bone marrow and peripheral blood compartments and, atypically, did not bind cognate antigen with high avidity. Differential staining intensities between antigen specificities likely reflect avidity ranges that lie within the capture window for each pHLA A*0201 tetrameric form.

Functional analysis.

Thawed BMMCs (up to 5 × 106 per experimental condition) were incubated overnight in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Gemini Bio-Product), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen) together with the costimulatory mAbs αCD28 and αCD49d (1 μg/mL each; BD Biosciences), brefeldin A (10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and PR1 peptide at a concentration of 10 μg/mL; negative controls in the absence of cognate peptide were processed in parallel. After incubation, the cells were washed twice in PBS, stained with ViViD as described in the previous subsection, washed in FACS buffer and then stained with surface marker-specific mAbs for 15 minutes at room temperature.

The cells were then washed again and permeabilized using the cytofix/cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instruc-tions before intracellular staining with mAbs specific for IFNγ, TNFα, IL-2, and MIP-1β. After a further wash in FACS buffer, the cells were fixed in 1% PFA. Data were collected immediately on a modified LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar) as described in the previous subsection; the gating strategy is illustrated in Figure 2.

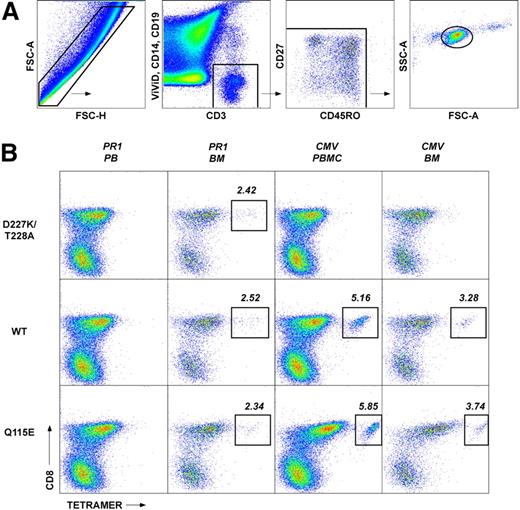

Functional verification of pHLA A*0201 tetramer staining for PR1-specific CD8+ T cells. BMMCs from patient 12 (Table 1) were stimulated with PR1 peptide at 10 μg/mL and stained with a panel of mAbs to assess cell surface phenotype and intracellular cytokine production as described in the Methods. (A) Gating strategy used to identify PR1-specific CD8+ T cells. The FSC-A versus FSC-H profile was used to exclude cell aggregates and large cells from the analysis; lymphocytes were then identified on the basis of light scatter characteristics. Live T cells were subsequently discriminated from dead cells, monocytes and B cells in a CD3 versus ViViD/CD14/CD19 bivariate plot before gating on CD8+ T cells. (B) Function and phenotype of PR1-specific CD8+ T cells. Background staining levels were assessed in control experiments processed identically in the absence of PR1 peptide (left panel). In the presence of PR1 peptide, 0.27% of memory CD8+ T cells expressed IFNγ (middle panel); no other cytokines were detected in this experiment (see “Methods”). Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells that produced IFNγ in response to PR1 peptide, depicted as colored dots superimposed on a cloud plot representing the phenotypic distribution of the total CD8+ T-cell population, displayed a heterogeneous memory phenotype (right panel) consistent with similar analyses conducted in conjunction with cognate pHLA A*0201 tetramer staining (Figure 4).

Functional verification of pHLA A*0201 tetramer staining for PR1-specific CD8+ T cells. BMMCs from patient 12 (Table 1) were stimulated with PR1 peptide at 10 μg/mL and stained with a panel of mAbs to assess cell surface phenotype and intracellular cytokine production as described in the Methods. (A) Gating strategy used to identify PR1-specific CD8+ T cells. The FSC-A versus FSC-H profile was used to exclude cell aggregates and large cells from the analysis; lymphocytes were then identified on the basis of light scatter characteristics. Live T cells were subsequently discriminated from dead cells, monocytes and B cells in a CD3 versus ViViD/CD14/CD19 bivariate plot before gating on CD8+ T cells. (B) Function and phenotype of PR1-specific CD8+ T cells. Background staining levels were assessed in control experiments processed identically in the absence of PR1 peptide (left panel). In the presence of PR1 peptide, 0.27% of memory CD8+ T cells expressed IFNγ (middle panel); no other cytokines were detected in this experiment (see “Methods”). Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells that produced IFNγ in response to PR1 peptide, depicted as colored dots superimposed on a cloud plot representing the phenotypic distribution of the total CD8+ T-cell population, displayed a heterogeneous memory phenotype (right panel) consistent with similar analyses conducted in conjunction with cognate pHLA A*0201 tetramer staining (Figure 4).

Results

Patient characteristics

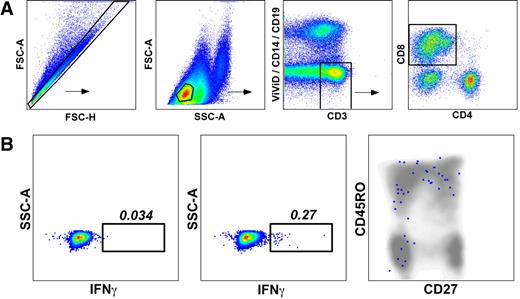

The current study was based on a cohort of 19 patients (median age, 38) with myeloid malignancies (AML, n = 10; CML, n = 9). Clinical and demographic data are summarized in Table 1, which is color-coded to correspond with the data shown in Figure 3. Sixteen patients received myeloablative conditioning followed by infusion of a T cell–depleted stem cell graft; T-cell chimerism data were available from 2000 onward. The median CD34+ cell dose was 3.2 × 106/kg.

Patient characteristics

Patients for whom chimerism analysis was not performed are denoted as  . Two patients died prior to achieving full donor chimerism.

. Two patients died prior to achieving full donor chimerism.

AML indicates acute myeloid leukemia; Bu, busulphan; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CR, complete remission; Cy, cyclophosphamide; F, female; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; M, male; MDS, myelodysplasia; Mel, melfalan; PD, progressive disease; TBI, total body irradiation; and TRM, transplantation-related mortality.

Leukemia-associated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells preferentially localize to the bone marrow in patients with myeloid malignancies. Cognate D227K/T228A, WT and Q115E pHLA A*0201 tetramers were used to quantify CD8+ T-cell populations specific for CMV pp65495-503, WT1126-134 and PR1 in the peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM). Graphs depict the frequency of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells within each compartment that bind to each pHLA A*0201 tetrameric form. Post-HSCT samples are shown as triangles and pre-HSCT samples are shown as circles; horizontal bars represent median values. Data are color-coded to match the key shown in Table 1. All pre-HSCT samples were drawn from time points before the conditioning regimen; post-HSCT samples were drawn at a median of 7.5 months (range, 2 to 28 months) from the date of transplant. Multiple time points were assessed in some patients, indicated by identical symbols. In some cases, not all cognate tetrameric forms were used due to limited cell availability. The differences between PB and BM were significant for PR1-specific CD8+ T-cell populations quantified with all 3 cognate tetramers (P = .003 with WT and Q115E, P < .001 with D227K/T228A; Mann-Whitney); there were no significant differences between compartments with respect to CMV-specific CD8+ T-cell populations.

Leukemia-associated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells preferentially localize to the bone marrow in patients with myeloid malignancies. Cognate D227K/T228A, WT and Q115E pHLA A*0201 tetramers were used to quantify CD8+ T-cell populations specific for CMV pp65495-503, WT1126-134 and PR1 in the peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM). Graphs depict the frequency of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells within each compartment that bind to each pHLA A*0201 tetrameric form. Post-HSCT samples are shown as triangles and pre-HSCT samples are shown as circles; horizontal bars represent median values. Data are color-coded to match the key shown in Table 1. All pre-HSCT samples were drawn from time points before the conditioning regimen; post-HSCT samples were drawn at a median of 7.5 months (range, 2 to 28 months) from the date of transplant. Multiple time points were assessed in some patients, indicated by identical symbols. In some cases, not all cognate tetrameric forms were used due to limited cell availability. The differences between PB and BM were significant for PR1-specific CD8+ T-cell populations quantified with all 3 cognate tetramers (P = .003 with WT and Q115E, P < .001 with D227K/T228A; Mann-Whitney); there were no significant differences between compartments with respect to CMV-specific CD8+ T-cell populations.

LAA-specific CD8+ T-cell populations localize selectively to the bone marrow

The avidity profiles and anatomical distribution of LAA-specific CD8+ T cells were determined using coreceptor-mutated pHLA A*0201 tetramers refolded around the WT1126-134 and PR1 peptide epitopes; identical evaluations were conducted in parallel for HLA A*0201-restricted CD8+ T-cell populations specific for the CMV pp65495-503 epitope. Representative data are shown in Figure 1, together with an illustration of the gating strategy used to eliminate irrelevant events from the analysis; specific effector function was verified by intracellular cytokine staining after exposure to cognate antigen (Figure 2) and the entire dataset is displayed in Figure 3. Remarkably, LAA-specific CD8+ T cells were almost exclusively confined to the bone marrow in patients with myeloid malignancies; in contrast, CD8+ T cells specific for CMV pp65495-503 were evenly distributed between the bone marrow and peripheral blood compartments. Thus, the median frequencies of CD8+ T cells specific for CMV pp65495-503 in the peripheral blood were 0.48% (range, 0 to 4.65%) with the D227K/T228A tetramer, 0.47% (range, 0.07 to 5.75%) with the WT tetramer, and 1.24% (range, 0.04 to 7.71%) with the Q115E tetramer; the corresponding median frequencies of PR1-specific and WT1-specific CD8+ T cells, respectively, were 0.01% (range, 0 to 0.04%) and 0.035% (range, 0 to 0.11%) with the D227K/T228A tetramers, 0.035% (range, 0 to 0.12%) and 0.07% (range, 0 to 0.3%) with the WT tetramers, and 0.035% (range, 0 to 0.18%) and 0.055% (range, 0 to 0.55%) with the Q115E tetramers. In the bone marrow, the median frequencies of CD8+ T cells specific for CMV pp65495-503 were 0.53% (range, 0 to 1.89%) with the D227K/T228A tetramer, 0.395% (range, 0 to 3.28%) with the WT tetramer, and 0.7% (range, 0 to 3.74%) with the Q115E tetramer; the corresponding frequencies of PR1-specific and WT1-specific CD8+ T cells, respectively, were 0.495% (range, 0 to 2.62%) and 0.2% (range, 0 to 0.66%) with the D227K/T228A tetramers, 1.24% (range, 0 to 2.52%) and 0.3% (range, 0 to 1.37%) with the WT tetramers, and 0.96% (range, 0.07 to 7.79%) and 0.38% (range, 0.07 to 4.86%) with the Q115E tetramers. Notably, PR1-specific CD8+ T-cell populations were readily detected in the bone marrow, whereas WT1-specific CD8+ T cells were less common. Furthermore, in all cases, PR1-specific CD8+ T cells detected in the bone marrow after HSCT engaged cognate antigen with high avidity as evidenced by D227K/T228A tetramer staining; thus, high avidity leukemia-specific CD8+ T cells are not necessarily disadvantaged in vivo. In contrast, PR1-specific CD8+ T cells identified before HSCT predominantly exhibited low avidity binding properties in 1 of 2 patients as evidenced by enhanced detection with the cognate Q115E tetramer; this is consistent with the deletion of high avidity tumor-specific CD8+ T cells in the autologous setting as described previously.21

Bone marrow–resident LAA-specific CD8+ T cells display distinct phenotypic characteristics

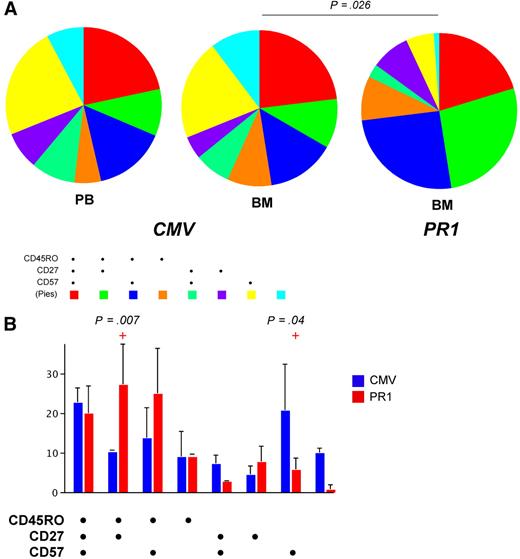

In conjunction with pHLA A*0201 tetramer staining, we determined the immunophenotype of CD8+ T cells specific for CMV pp65495-503, WT1126-134 and PR1 by incorporating mAbs specific for CD27, CD45RO, and CD57 into the flow cytometric panel. Importantly, all CD8+ T cells specific for the same antigen within each patient that were identified with more than 1 cognate tetrameric form displayed identical phenotypic characteristics (data not shown); thus, while pMHCI tetramers are not biologically inert, differential coreceptor binding properties do not skew phenotypic analysis, at least with respect to the markers used in this study. Significant immunophenotypic differences were observed between CD8+ T-cell populations specific for CMV pp65495-503 and PR1 within the bone marrow compartment. Thus, PR1-specific CD8+ T cells were significantly skewed toward a central memory–like phenotype compared with CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, which contained a greater proportion of terminally differentiated CD27−CD45RO−CD57+ cells (Figure 4). There were no significant immunophenotypic differences between CMV-specific CD8+ T-cell populations in the peripheral blood and bone marrow compartments (Figure 4).

Phenotypic characteristics of CD8+ T-cell populations specific for CMV pp65495-503 and PR1 in peripheral blood and bone marrow. Cognate WT pHLA A*0201 tetramers were used to identify antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell populations in a polychromatic flow cytometric panel that included mAbs to determine the expression of surface markers commonly used to distinguish naive and memory T cells. (A) Pie charts depict the proportions of CMV-specific and PR1-specific CD8+ T cells that expressed various combinations of CD27, CD45RO, and CD57, as indicated by the adjoining key. The phenotypic composition of CMV-specific CD8+ T cells was not significantly different between the peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) compartments; however, within the bone marrow, the phenotypic composition of CMV-specific and PR1-specific CD8+ T-cell populations was significantly different. (B) Bar graphs show the proportions of CMV-specific and PR1-specific CD8+ T cells that expressed each combination of CD27, CD45RO, and CD57 in the bone marrow. Compared with CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, PR1-specific CD8+ T-cell populations were significantly enriched for CD27+CD45RO+CD57− (central memory–like) cells and depleted of CD27−CD45RO−CD57+ (terminally differentiated) cells.

Phenotypic characteristics of CD8+ T-cell populations specific for CMV pp65495-503 and PR1 in peripheral blood and bone marrow. Cognate WT pHLA A*0201 tetramers were used to identify antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell populations in a polychromatic flow cytometric panel that included mAbs to determine the expression of surface markers commonly used to distinguish naive and memory T cells. (A) Pie charts depict the proportions of CMV-specific and PR1-specific CD8+ T cells that expressed various combinations of CD27, CD45RO, and CD57, as indicated by the adjoining key. The phenotypic composition of CMV-specific CD8+ T cells was not significantly different between the peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) compartments; however, within the bone marrow, the phenotypic composition of CMV-specific and PR1-specific CD8+ T-cell populations was significantly different. (B) Bar graphs show the proportions of CMV-specific and PR1-specific CD8+ T cells that expressed each combination of CD27, CD45RO, and CD57 in the bone marrow. Compared with CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, PR1-specific CD8+ T-cell populations were significantly enriched for CD27+CD45RO+CD57− (central memory–like) cells and depleted of CD27−CD45RO−CD57+ (terminally differentiated) cells.

Relationship between the presence of LAA-specific CD8+ T cells in bone marrow and clinical outcome

Overall, 7 patients remain alive and in remission, 8 patients died of progressive disease, 2 patients had transplantation-related mortality, 1 patient died of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after a donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI), and 1 patient died of septicemia 3 years after HSCT (Table 1). Of the 9 patients who were alive 3 years after HSCT and in remission, 6 were tested for the presence of HLA A*0201-restricted CD8+ T cells specific for PR1 and WT1126-134 in the bone marrow. In all 6 patients, high avidity PR1-specific CD8+ T cells were detected after transplantation (Table 1 and Figure 3). Of the 7 patients who relapsed within 3 years of transplantation, only 2 had LAA-specific CD8+ T cells in the bone marrow; PR1-specific CD8+ T cells were identified in one of these relapsing patients who had severe grade III/IV GVHD requiring augmentation of immunosuppressive therapy after HSCT, and both patients died within 6 months of transplantation. Thus, the presence of high avidity PR1-specific CD8+ T cells in the bone marrow is associated with clinical remission, thereby suggesting a protective role for these cells after HSCT.

Discussion

In this study, we used coreceptor-mutated pHLA A*0201 tetrameric complexes and polychromatic flow cytometry to examine the avidity, phenotype and localization of LAA-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with myeloid leukemias. The principal findings were that: (1) LAA-specific CD8+ T cells localize preferentially to the bone marrow; (2) PR1-specific CD8+ T cells are more prevalent than WT1-specific CD8+ T cells; (3) all PR1-specific CD8+ T-cell populations detected in the bone marrow after HSCT bound cognate antigen with high avidity, whereas this was not necessarily the case before HSCT; (4) the presence of high avidity PR1-specific CD8+ T cells was associated with clinical remission; and, (5) bone marrow–resident PR1-specific CD8+ T cells displayed distinct phenotypic charateristics compared with CMV-specific CD8+ T-cell populations in the same compartment, with marked skewing toward a central memory–like phenotype.

To date, most studies of T-cell immunity in the setting of leukemic states have focused on analyses of samples derived from the peripheral blood and, in general, have struggled to identify clearly defined populations of LAA-specific CD8+ T cells. Consequently, it has proven difficult to establish consistent immunologic correlates of protection and GVL-mediated effects. The demonstration herein that LAA-specific CD8+ T cells localize almost exclusively to the bone marrow provides a rationale for the extension of current immunologic analyses to additional anatomical compartments in the quest for a more comprehensive understanding of interactions between leukemias and the immune system. Nonlymphoid tissues, and the bone marrow in particular, have previously been reported to act as reservoirs for central memory T cells.22-24 Thus, T cells can migrate to multiple tissues after activation by cognate antigen but appear to persist preferentially in nonlymphoid tissues.25 Furthermore, T cells that mount responses to specific agents in nonlymphoid tissues can be retained close to the site of infection long after the inciting antigen has become undetectable, thereby providing a primed response anatomically poised to control recurrent events.26,27 Previous studies have reported T cells specific for infectious agents,22-25,28,29 alloantigens,30 ovalbumin,31 and tumor antigens32-39 within the bone marrow; the present data confirm and extend these findings to the setting of myeloid leukemias. Given that the bone marrow is the site of primary pathology in the leukemic process and can also act as a natural niche for the homeostatic retention and proliferation of memory T cells,31,40 it is difficult to disentangle physiologic residence from antigen-dependent localization based on the current dataset. However, it seems likely that both processes occur in light of the phenotypic heterogeneity of LAA-specific CD8+ T-cell populations within the bone marrow and their presence both during the active leukemic process before HSCT and after achievement of clinical remission post-HSCT (Figure 3).

It is established in several systems that high avidity antigen-specific CD8+ T cells are more efficacious than their lower avidity counterparts.41 In this light, the presence of high avidity LAA-specific CD8+ T cells in the bone marrow is encouraging, especially in the allogeneic setting after HSCT. Indeed, the preliminary association between such CD8+ T-cell populations and clinical remission in the present cohort hints at a mechanistic explanation for protective GVL-mediated effects, although larger studies are needed to confirm these findings. Previous studies have suggested that high avidity LAA-specific CD8+ T cells are deleted in vivo21 ; similar findings in other systems support the general applicability of this phenomenon under conditions of high antigen load.41 Furthermore, biophysical analyses of TCRs derived from tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell clones have demonstrated that such TCRs bind cognate antigen with lower affinities at the monomeric level compared with pathogen-specific TCR/pMHCI interactions.42 Consistent with these findings, we did not detect high avidity LAA-specific CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood. However, the observation that such cells can persist in the bone marrow offers hope that preferential deletion effects may not necessarily compromise immunotherapeutic approaches to the treatment of leukemias. Indeed, after HSCT, the maintenance of high avidity CD8+ T cells poised to respond at the site of leukemogenesis may provide long-term protection against recurrence.

In summary, we have shown that high avidity LAA-specific CD8+ T cells preferentially localize to the bone marrow in patients with myeloid leukemias, both before and after HSCT. These data indicate that immunologic analyses of bone marrow specimens might contribute useful information in the search for correlates of protective leukemia-specific immunity and GVL-mediated effects.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the NHLBI. D.A.P. is a Medical Research Council (UK) Senior Clinical Fellow.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contributions: J.J.M., P.S., P.K.C., and D.A.P. designed experiments; J.J.M., P.S., P.K.C., E.G., K.L., N.F.H., and D.A.P. performed research; J.J.M., P.S., P.K.C., K.L., M.R., and D.A.P. analyzed data; E.G. and D.A.P. constructed new reagents; P.S., N.F.H., and A.J.B. provided clinical input; and J.J.M., P.S., P.K.C., D.C.D., and D.A.P. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: J. Joseph Melenhorst, Hematology Branch, NHLBI, NIH, Bethesda, MD, 20892; e-mail: melenhoj@nhlbi.nih.gov; and David A. Price, Department of Medical Biochemistry and Immunology, Cardiff University School of Medicine, Cardiff, CF14 4XN, Wales, United Kingdom; e-mail: priced6@cardiff.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal