Abstract

Inactivation of the tumor suppressor gene, CDKN2A, can occur by deletion, methylation, or mutation. We assessed the principal mode of inactivation in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and frequency in biologically relevant subgroups. Mutation or methylation was rare, whereas genomic deletion occurred in 21% of B-cell precursor ALL and 50% of T-ALL patients. Single nucleotide polymorphism arrays revealed copy number neutral (CNN) loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in 8% of patients. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization demonstrated that the mean size of deletions was 14.8 Mb and biallelic deletions composed a large and small deletion (mean sizes, 23.3 Mb and 1.4 Mb). Among 86 patients, only 2 small deletions were below the resolution of detection by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Patients with high hyperdiploidy, ETV6-RUNX1, or 11q23/MLL rearrangements had low rates of deletion (11%, 15%, 13%), whereas patients with t(9;22), t(1;19), TLX3, or TLX1 rearrangements had higher frequencies (61%, 42%, 78%, and 89%). In conclusion, CDKN2A deletion is a significant secondary abnormality in childhood ALL strongly correlated with phenotype and genotype. The variation in the incidence of CDKN2A deletions by cytogenetic subgroup may explain its inconsistent association with outcome. CNN LOH without apparent CDKN2A inactivation suggests the presence of other relevant genes in this region.

Introduction

Genetic alterations including chromosomal translocation, promoter hypermethylation, somatic mutation, and gene deletion are thought to play a key role in oncogenesis. Alterations of the 9p21 locus have been implicated in many types of cancer, indicating a role for the tumor suppressor genes CDKN2A (MTS1) and CDKN2B (MTS2), which encode for p16INK4a/p14ARF and p15INK4b, respectively.1 Loss of cell proliferation control and regulation of the cell cycle are known to be critical to cancer development.2 Both p16INK4a and p15INK4b specifically inhibit cyclin/CDK-4/6 complexes that block cell division during the G1/S phase of the cell cycle.3

It has been reported that CDKN2A and CDKN2B are frequently inactivated in various hematologic malignancies.1,4 Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome arm 9p, including the CDKN2A locus, is one of the most frequent genetic events in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), suggesting inactivation of the second allele or, possibly, haploinsufficiency.5-8 Haploinsufficiency of a tumor suppressor gene, eg, CDKN2A, has been shown to be adequate to promote tumor progression.9-11 Homozygous deletion of CDKN2A has been suggested as the dominant mechanism of its inactivation in leukemogenesis.12 However, the reported frequencies of both heterozygous and homozygous deletions in childhood ALL vary, 9% to 27% and 6% to 33% in B-cell precursor (BCP) ALL and 7% to 18% and 30% to 83% in T-ALL, respectively.13 Similarly, the frequency of hypermethylation of the CDKN2A promoter has been reported to vary from 0% to 40% in childhood ALL.14-19 Although mutations in exons 1 and 2 of CDKN2A have been described in childhood ALL, their incidence appears to be low, ranging from 0% to 7%.12,20-24

As reported data on CDKN2A alterations in childhood ALL are discrepant, it remains important to reveal the role of this gene in cancer development. In this study, we have used mutation and methylation analyses as well as genomic technologies to elucidate the principal mode of CDKN2A inactivation in childhood ALL. Moreover, the use of array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray mapping has allowed the architecture of CDKN2A deletions in this disease to be characterized. Finally, extensive screening using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has enabled the frequency of deletions to be accurately determined in biologically relevant subgroups.

Methods

Patient samples

Diagnostic or relapse samples were obtained from patients entered to a National Cancer Research Institute Childhood Cancer and Leukemia Group treatment trial (UKALLXI, ALL97, or ALL2003) or treated locally within the Northern Region of the United Kingdom after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trials described herein were registered at ISRCTN (http://www.controlled-trials.com/isrctn/) as follows: ALL2003 as no. 07355119, ALL97 as no. 26727615, and UKALLXI as no. 16757172. All patients were diagnosed between 1986 and 2007. Cytogenetic and FISH data from diagnostic and relapse samples were collected either by the Leukaemia Research Fund United Kingdom Cancer Cytogenetics Group Karyotype Database25 or the National Health Service Northern Genetics Service. Institutional Review Board approval was provided by each participating institution. Peripheral blood lymphocytes were obtained from a healthy participant for use as a normal control. Genomic DNA was extracted from mononuclear cells after density gradient centrifugation using a commercial kit (QiAmp DNA Blood Kit; QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Mutation analysis

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification for each exon was performed in 50-μL volume assays containing 1× PCR buffer, 200 μM deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate mix, 1.5 to 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 to 0.4 μM of each primer, 1.25 U of Amplitaq Gold polymerase, and 100 ng of genomic DNA. In addition, a final concentration of 2.5% dimethyl sulfoxide was used in the exon 2 reaction mixture. Primer pairs for exons 1, 2, and 3 were previously described.20,26 PCR conditions for exon 1 and 2 consisted of initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 56°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. The final extension at 72°C was performed for 5 minutes. PCR amplification of exon 3 was carried out using Touchdown protocol consisting of initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 14 cycles (20 seconds denaturation at 94°C, 1 minute annealing at 65°C to 58°C with a decrease of 0.5°C every cycle, and 1 minute extension at 72°C) and a further 20 cycles with annealing at 58°C for 1 minute. All PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) transillumination.

Mutation screening of all exons was performed using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (dHPLC; WAVE Nucleic Acid Fragment Analysis System; Transgenomic, Cramlington, United Kingdom). All PCR products showing homoduplex profiles were spiked with approximately equimolar proportions of a product known to contain a wild-type CDKN2A fragment, and rescreened to differentiate between wild-type homozygote and homozygote variants. DNA from a melanoma cell line (MM384) kindly provided by Dr Nicholas Hayward (Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Queensland, Australia) and a myeloid leukemia cell line (HL60), known to contain CDKN2A mutations were used as positive controls for exons 1a and 2, respectively. Heteroduplex profiles for MM384 and HL60 cell lines were detected after spiking consistent with their homozygous mutant status. All samples showing an altered dHPLC profile were directly sequenced or cloned and then sequenced using standard methods (Pinnacle Laboratory, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom).

Methylation analysis

The methylation status of the CDKN2A promoter regions was assessed by methylation-specific PCR (MSP) analysis. DNA modification (bisulphite treatment) was conducted by using the CpGenome DNA Modification Kit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). A total of 250 ng of DNA was treated according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA from Raji and HL60 cell lines were used as controls for methylated and unmethylated CDKN2A, respectively, as previously described.3 All bisulphite-treated DNA samples were amplified by using the primer sets specific for the unmethylated and methylated CDKN2A sequences (referred to as p16U and p16M, respectively), as previously reported.27 The final concentration of the reagents in the PCR mixture was 1× PCR buffer, 200 μM deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate mix, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM of each primer set for p16U and p16M, 1.25 U of Amplitaq Gold polymerase, and bisulphite-modified DNA (50 ng) in a final volume of 25 μL. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 14 cycles (20 seconds denaturation at 94°C, 1 minute annealing at 64°C to 57°C with a decrease of 0.5°C every cycle, and 1 minute extension at 72°C) and a further 32 cycles with annealing at 57°C for 1 minute. Each PCR product was directly loaded onto 1.8% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV transillumination. MSP analysis was repeated for each patient sample to confirm the methylation status of CDKN2A.

Single nucleotide polymorphism mapping array

DNA samples at relapse and presentation were analyzed using a GeneChip Human Mapping 10K and/or 50K array (Affymetrix United Kingdom, High Wycombe, United Kingdom) to characterize LOH and allele copy number. Each SNP on the array is represented by 40 different 25-bp oligonucleotides, each with slight variations that allow accurate genotyping. Sample analysis was performed by MRC Geneservice (Hinxton, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Data from microarray analysis were analyzed using the Copy Number Analyser for Affymetrix GeneChip software package (version 1.1), to identify regions of chromosomal deletion, amplification, or LOH.28

aCGH analysis

aCGH was performed with array platforms constructed from either large-insert DNA clones or oligonucleotides, offering genome coverage at 1-Mb and 6-kb intervals, respectively. For the large insert arrays, DNA samples were processed in a dye-swap combination and sex-matched with DNA extracted from phenotypically normal participants (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom) before hybridization to 2 commercially available systems (Spectral Genomics and IntegraGen; Genosystems, Paris, France), as previously reported.29 For the oligonucleotide array, sample DNA was sex-matched to the same control DNA and hybridized to the 244K whole genome array (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.30 Scanning, grid placement, spot quality, data normalization, fluorescence quantification, postprocessing of the array image, and data analysis were performed as previously described.31,32 Regions of copy number alteration, identified by the large-insert array, were defined as a minimum of 3 adjacent clones simultaneously deviating beyond the threshold values in both dye-swap experiments and were positioned onto the human genome sequence using BlueFuse software (BlueGnome, Cambridge, United Kingdom). For the oligonucleotide array analysis, CGH Analytics software (Agilent Technologies) was used to identify regions of copy number alteration based on the z-score and mathematical aberration detection analysis (ADM1; Agilent Technologies).

FISH

FISH analysis was performed on frozen cytospins and/or fixed cells from diagnostic bone marrow. Three commercial probes were used to detect CDKN2A deletions in leukemic cells: LSI p16 (9p21) SpectrumOrange/CEP 9 SpectrumGreen Probe (Vysis/Abbott Diagnostics, Maidenhead, United Kingdom), P16 Deletion Probe (Cytocell Technologies, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and p16 (CDKN2A) specific probe (Qbiogene/MP Biomedicals, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Probe and slide preparation as well as hybridization and washing steps were performed according to the manufacturers' protocols. An additional home-grown dual-color, CDKN2A deletion probe (consisting of BAC RP11-149I2/70L8 and the chromosome 9 centromere probe pMR9A; all clones from Sanger Institute, Hinxton, United Kingdom; and Wessex Regional Genetics Laboratory [WRGL], Salisbury, United Kingdom) was also used. These were grown and labeled for FISH as previously described.33 The approximate size of the p16/CDKN2A probes are: Vysis, 190 kb; Cytocell, 101 kb; Qbiogene, not available; WRGL, 101 kb. A minimum of 100 interphase cells were scored in each test. A signal pattern of 2 red and 2 green (2R2G) was considered to represent a normal cell. Loss of one signal corresponding to the test and retention of both signals for the control probe (ie, 1R2G or 2R1G depending on the probe) were considered to represent a heterozygous deletion. A homozygous deletion was defined as loss of both test signals with retention of both control signals (ie, 0R2G or 2R0G depending on the probe). The cutoff level defined to rule out a false-positive result was calculated to be 5%. Therefore, only abnormal cell populations composing more than 5% of analyzed cells were included. Rare cases with 2 different deleted populations (one heterozygous and one homozygous) were classified as having a homozygous deletion. Cases with loss of a whole chromosome 9 were not classified as having a deletion.

Results

Mutation screening

Mutation screening of all 3 exons was successfully performed on 47 patients who were known to have retained (by FISH or single nucleotide polymorphism mapping array [SNPA]) at least one CDKN2A allele. Samples tested were from diagnosis (n = 21), relapse (n = 25), or both time points (n = 1; Table 1). Chromatography profiles generated from dHPLC were inspected to detect heteroduplexes that indicated the presence of mutations/polymorphisms. All aberrant profiles were confirmed by DNA sequencing analysis. A known SNP was detected in 15 (32%) patients: detected at diagnosis (n = 4), relapse (n = 10), or both time points (n = 1). Nine (19%) patients had the 500C>G SNP in the 3′UTR of exon 3: 7 (15%) patients were CG heterozygotes, whereas 2 (4%) were GG homozygotes. Three patients who were CG heterozygotes at nucleotide 500 also carried the A148T polymorphism in exon 2. Six (13%) patients had the 540C>T polymorphism in the 3′UTR of exon 3: 4 (9%) patients were CT heterozygotes, whereas 2 (4%) were TT homozygotes. Only one patient (L5C) harbored a somatic mutation. This was detected in a relapse sample and involved a base substitution of C>T in exon 2 at nucleotide 247, which resulted in the amino acid tyrosine replacing histidine at codon 83 (H83Y). Although this relapse sample showed an aberrant profile after dHPLC, initially no mutation was detected by sequencing analysis. DNA from this patient was cloned and after resequencing the mutation was confirmed in 2 of 20 clones, suggesting that the quantity of mutant DNA was too low to be detected by first direct sequencing. We concluded that only a minority of the blast cells harbored this mutation, which was detected by the sensitive dHPLC technique but not by direct sequencing, in agreement with a previous study.34 This patient had a normal karyotype and did not show loss of CDKN2A by FISH. However, SNP array analysis revealed copy number neutral (CNN) LOH from 9p21.1 to the telomere.

Number of patient samples tested by each technique and at each time point

| Technique . | No. of patients . | No. of samples . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis . | Relapse . | Both time points . | ||

| Mutation screening | 47 | 22 | 26 | 1 |

| Methylation status | 99 | 73 | 29 | 3 |

| SNP array | 98 | 86 | 20 | 8 |

| Array CGH | 105 | 103 | 3 | 1 |

| FISH | 1171 | 1130 | 77 | 36 |

| Technique . | No. of patients . | No. of samples . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis . | Relapse . | Both time points . | ||

| Mutation screening | 47 | 22 | 26 | 1 |

| Methylation status | 99 | 73 | 29 | 3 |

| SNP array | 98 | 86 | 20 | 8 |

| Array CGH | 105 | 103 | 3 | 1 |

| FISH | 1171 | 1130 | 77 | 36 |

SNP indicates single nucleotide polymorphism; CGH, comparative genomic hybridization; and FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Methylation screening

MSP analysis was performed on a total of 99 patients who were known to have retained (by FISH or SNPA) at least one CDKN2A allele (Table 1). Samples tested were from diagnosis (n = 70), relapse (n = 26), or both time points (n = 3). Each assay was performed twice and included a positive control (Raji cell line in which CDKN2A is methylated) and a negative control (HL60 cell line in which CDKN2A is unmethylated). The presence of a 151-bp and a 150-bp product in the relevant lane indicated that the sample was umethylated (U) and methylated (M), respectively. None of the patients showed complete methylation of the CDKN2A promoter, but 1 patient had partial methylation as shown by the presence of both U and M products. Partial methylation suggests the presence of a mixed population of blasts: 1 with and 1 without methylation of the CDKN2A promoter. This patient had a normal karyotype, did not have a mutation, and had an intact 9p by aCGH.

Genomic analyses

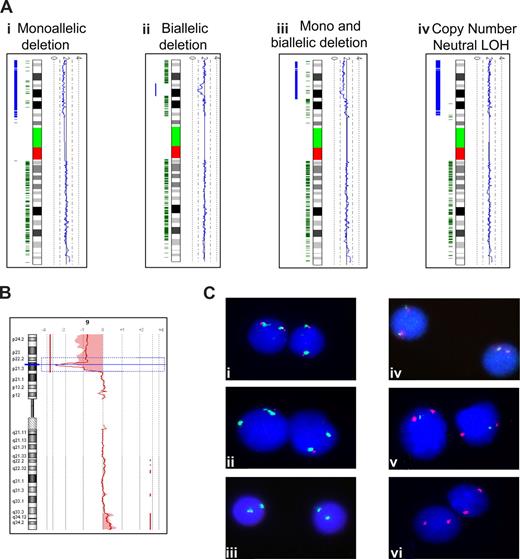

High-density SNPA analyses were performed on 98 patients at diagnosis (n = 78), relapse (n = 12), or both time points (n = 8; Table 1). No abnormality of the short arm of chromosome 9 was detected in 73 (74%) patients, whereas 25 (26%) patients harbored either a deletion (n = 17) or CNN LOH (n = 8) of 9p. The absence of a 9p deletion was confirmed in 27 patients by FISH (n = 8), aCGH (n = 11), or both techniques (n = 8). SNPA revealed a deletion of 9p in 17 (17%) patients (Figure 1Ai-iii). Most of the deletions were terminal [n = 11: del(9)(p12)x1, del(9)(p13.1)x1, del(9)(p13.2)x1, del(9)(p13.3)x4, del(9)(p21.2)x1 and del(9)(p21.3)x3]; but interstitial deletions also occurred [n = 6: del(9)(p21.2p21.3)x1, del(9)(p21.3p22.1)x2, del(9)(p21.3p22.3)x1, del(9)(p21.3p21.3)x2]. All the deletions were confirmed by FISH (n = 10), aCGH (n = 2), or both techniques (n = 5). In addition to these deletions, SNPA revealed CNN LOH (also known as acquired isodisomy and uniparental disomy) in 8 (8%) patients at diagnosis (n = 6) and relapse (n = 2). The area of CNN LOH (Figure 1Aiv) ranged from approximately 28 Mb to the whole chromosome: 9p21.1- > 9pter (n = 2), 9p13- > 9pter (n = 1), 9q21- > 9pter (n = 1), and whole chromosome 9 (n = 4). None of these patients showed a CDKN2A deletion by FISH (n = 7 tested) or promoter hypermethylation (n = 8). However, 1 patient did harbor a H83Y mutation in exon 2 of CDKN2A. A high hyperdiploid karyotype was detected in 5 of these 8 patients, including 3 of the 4 patients with whole chromosome 9 CNN LOH, but 2 normal copies of chromosome 9 were seen by cytogenetics. Cytogenetics failed or was normal in the remaining 3 patients.

Genomic mapping of chromosome arm 9p. (A) Profiles generated using the copy number analyzer for Affymetrix GeneChip software. Ideograms of chromosome 9 are positioned vertically and flanked by a blue copy number plot to the right, which follows 2.0 for normal copy number. To the left of each ideogram, heterozygous SNP calls are shown in green, and the likelihood of LOH is represented by the thickness of the blue bar. Thus, the 4 profiles show a patient with (i) a monoallelic terminal deletion of 9p, (ii) an interstitial biallelic deletion, (iii) both a terminal monoallelic and interstitial biallelic deletion, and (iv) CNN LOH. (B) An array CGH profile for chromosome 9. The chromosome ideogram is positioned vertically with the red line following a log ratio of 0.0 for normal copy number. This profile shows a patient with a terminal monoallelic and interstitial biallelic deletion. The shaded areas define regions of copy number change ac-cording to a z-score algorithm. (C) FISH analysis. Vysis p16(9p21) (red)/CEP9 (green) probe showing (i) normal pattern, (ii) monoallelic deletion, or (iii) biallelic deletion. WRGL CDKN2A (green)/Centromere 9 (red) deletion probe showing (iv) normal pattern, (v) monoallelic deletion, or (vi) biallelic deletion.

Genomic mapping of chromosome arm 9p. (A) Profiles generated using the copy number analyzer for Affymetrix GeneChip software. Ideograms of chromosome 9 are positioned vertically and flanked by a blue copy number plot to the right, which follows 2.0 for normal copy number. To the left of each ideogram, heterozygous SNP calls are shown in green, and the likelihood of LOH is represented by the thickness of the blue bar. Thus, the 4 profiles show a patient with (i) a monoallelic terminal deletion of 9p, (ii) an interstitial biallelic deletion, (iii) both a terminal monoallelic and interstitial biallelic deletion, and (iv) CNN LOH. (B) An array CGH profile for chromosome 9. The chromosome ideogram is positioned vertically with the red line following a log ratio of 0.0 for normal copy number. This profile shows a patient with a terminal monoallelic and interstitial biallelic deletion. The shaded areas define regions of copy number change ac-cording to a z-score algorithm. (C) FISH analysis. Vysis p16(9p21) (red)/CEP9 (green) probe showing (i) normal pattern, (ii) monoallelic deletion, or (iii) biallelic deletion. WRGL CDKN2A (green)/Centromere 9 (red) deletion probe showing (iv) normal pattern, (v) monoallelic deletion, or (vi) biallelic deletion.

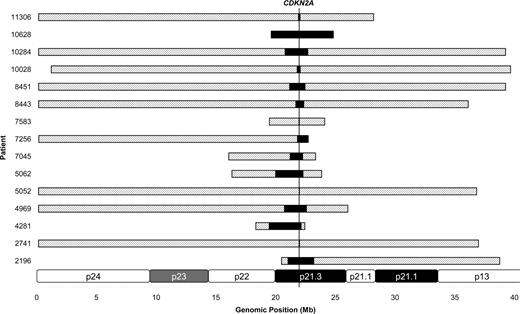

A selected series of patients (n = 105) were analyzed using aCGH at diagnosis (n = 102), relapse (n = 2), or both time points (n = 1; Table 1; Figure 1B). Overall, 34 (32%) patients harbored a deletion of CDKN2A, including 15 who showed biallelic loss (Figure 2). FISH analysis confirmed the presence of a CDKN2A deletion in 19 of 20 (95%) patients tested. One patient showed a very small (0.045 Mb) monoallelic deletion of CDKN2A that was below the resolution of the commercial or home-grown FISH probes. In another patient (patient 2741), aCGH detected a large (36.7 Mb) monoallelic deletion accompanied by a very small (0.025 Mb) biallelic deletion, the latter of which was below the resolution of either FISH probe. The size of the deletions varied considerably from 0.025 Mb to 39.1 Mb, with a mean of 14.5 Mb and median of 7.3 Mb. Among 15 patients with biallelic deletions, a pattern of one large and one small deletion was evident (Figure 2). The mean size of the larger deletion was 23.3 Mb, whereas the smaller deletion was more focal with a mean size of 1.4 Mb: 7 of 15 biallelic deletions were less than 1 Mb.

Diagrammatic representation of 15 biallelic deletions as assessed by array CGH analysis. The shaded bars represent the size of the monoallelic deletion; black bar represents the size of the biallelic deletion. The genomic location of CDKN2A is shown by the vertical line. A partial ideogram of chromosome 9p is shown at the bottom for reference.

Diagrammatic representation of 15 biallelic deletions as assessed by array CGH analysis. The shaded bars represent the size of the monoallelic deletion; black bar represents the size of the biallelic deletion. The genomic location of CDKN2A is shown by the vertical line. A partial ideogram of chromosome 9p is shown at the bottom for reference.

Correlation of CDKN2A deletions with demographic and cytogenetic features

To assess the true incidence of CDKN2A deletions in childhood ALL as a whole and within relevant biologic subgroups, an extensive interphase FISH screening program was carried out. Three independent and unbiased cohorts were identified as follows: 864 diagnostic samples from patients with BCP-ALL, 266 diagnostic samples from patients with T-ALL, and a relapse cohort comprising 69 BCP-ALL and 8 T-ALL patients. A total of 1207 samples were screened with one of 4 FISH probes: Vysis, Cytocell, Qbiogene, and WRGL (Table 1). However, the majority of samples (96%) were tested with either the Vysis probe (n = 515), WRGL probe (n = 870), or both (n = 216). Among 226 samples tested with more than one FISH probe, only 11 (< 5%) cases showed discrepant results. In 4 cases, the WRGL probe detected a biallelic deletion, whereas the Vysis probe had detected only a monoallelic deletion. In the other 7 cases, no deletion was detected by the Vysis probe, whereas the WRGL or Qbiogene probe detected a monoallelic (n = 5) or biallelic (n = 2) deletion. These discrepancies are the result of the fact that the Vysis probe is approximately 90 kb larger than the WRGL or Qbiogene probes. Conventional cytogenetics was attempted on virtually all these samples (1197 of 1207, 99%) and was of sufficient quality to assess 9p status in 884 (73%). A cytogenetically visible 9p deletion/abnormality was detected in 133 of 277 (48%) samples where FISH detected a deletion. In a small number of samples (n = 19), a cytogenetically visible 9p abnormality did not correlate with a deletion of CDKN2A.

The incidence of CDKN2A deletions and the proportion of biallelic deletions present at diagnosis were higher in T-ALL patients compared with BCP-ALL patients: 50% versus 21% (P < .001) and 62% versus 43% (P = .001), respectively (Table 2). Among BCP-ALL patients, CDKN2A deletions were more prevalent among older children (10+ years, P < .001) and those with a white cell count (WCC) of greater than 50 × 109/L (P < .001). However, this was not the situation among T-ALL patients (Table 2). Moreover, within the BCP-ALL and T-ALL cohorts, the incidence of CDKN2A deletions was associated with specific cytogenetic subgroups. The incidence of deletions was significantly lower among BCP-ALL patients with the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion or high hyperdiploidy, whereas it was significantly higher among patients with t(9;22)(q34;q11) or t(1;19)(q23;p13) (Table 2). Among T-ALL patients, those with involvement of TLX1 or TLX3 had significantly higher rates of deletion compared with T-ALL patients without these abnormalities (Table 2). Considering BCP-ALL and T-ALL patients together, CDKN2A deletions were rare among those with MLL translocations (4 of 33, 12%, vs 285 of 1012, 28%; P < .05). However, the difference was not significant when BCP-ALL and T-ALL patients were considered separately (Table 2). Among 10 patients with t(4;11)(q21;q23), only 1 had a homozygous deletion of CDKN2A and none of the 9 patients with t(11;19)(q23;p13) harbored a deletion. Despite the incidence of CDKN2A deletions varying markedly by immunophenotype, age, WCC, and cytogenetic subgroup, the proportion of biallelic deletions was relatively stable: 40% among BCP-ALL and 60% among T-ALL patients. Two possible exceptions were t(9;22) patients with BCP-ALL and those with normal karyotypes, where monoallelic and biallelic deletions dominated, respectively (Table 2).

Incidence of CDKN2A deletions by sex, age, white cell count, and cytogenetic subgroup in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)

| Subgroup . | BCP-ALL cohort . | T-ALL cohort . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total . | Deletion, n (%) . | Biallelic deletion, n (% of deleted cases) . | . | Total . | Deletion, n (%) . | Biallelic deletion, n (% of deleted cases) . | |

| Total | 864 | 180 (21) | 78 (43) | 266 | 134 (50) | 83 (62) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 473 | 96 (20) | 43 (45) | 191 | 96 (50) | 63 (66) | |

| Female | 391 | 84 (21) | 35 (42) | 75 | 38 (51) | 20 (53) | |

| Age groups | |||||||

| < 10 y | 679 | 129 (19)g | 53 (41) | 141 | 81 (57)g | 47 (58) | |

| 10+ y | 185 | 51 (28)g | 25 (49) | 125 | 53 (42)g | 36 (68) | |

| White cell counta | |||||||

| < 50 × 109/L | 636 | 109 (17)h | 50 (46) | 82 | 37 (45) | 23 (62) | |

| > 50 × 109/L | 154 | 55 (36)h | 19 (35) | 172 | 88 (51) | 55 (63) | |

| Cytogenetic subgroupsb | Cytogenetic subgroupsb | ||||||

| High hyperdiploidyc | 279 | 30 (11)h | 14 (47) | TAL1 rearrangementsi | 49 | 21 (43) | 12 (57) |

| ETV6-RUNX1 | 218 | 33 (15)g | 15 (45) | TLX3 rearrangementsj | 41 | 31 (76)h | 18 (58) |

| t(1;19)(q23;p13) | 25 | 10 (40)g | 2 (20) | LMO2 rearrangementsk | 23 | 9 (39) | 6 (67) |

| MLL translocationsd | 22 | 2 (9) | 1 (50) | MLL translocationsd | 11 | 2 (18) | 1 (50) |

| t(9;22)(q34;q11) | 19 | 11 (58)h | 1 (9)g | TLX1 abnormalitiesl | 9 | 8 (89)g | 4 (50) |

| iAMP21e | 19 | 5 (26) | 3 (60) | AF10-CALM | 9 | 4 (44) | 1 (25) |

| Normal karyotypef | 52 | 6 (12) | 6 (100)h | Normal karyotypef | 55 | 23 (42) | 18 (78) |

| Subgroup . | BCP-ALL cohort . | T-ALL cohort . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total . | Deletion, n (%) . | Biallelic deletion, n (% of deleted cases) . | . | Total . | Deletion, n (%) . | Biallelic deletion, n (% of deleted cases) . | |

| Total | 864 | 180 (21) | 78 (43) | 266 | 134 (50) | 83 (62) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 473 | 96 (20) | 43 (45) | 191 | 96 (50) | 63 (66) | |

| Female | 391 | 84 (21) | 35 (42) | 75 | 38 (51) | 20 (53) | |

| Age groups | |||||||

| < 10 y | 679 | 129 (19)g | 53 (41) | 141 | 81 (57)g | 47 (58) | |

| 10+ y | 185 | 51 (28)g | 25 (49) | 125 | 53 (42)g | 36 (68) | |

| White cell counta | |||||||

| < 50 × 109/L | 636 | 109 (17)h | 50 (46) | 82 | 37 (45) | 23 (62) | |

| > 50 × 109/L | 154 | 55 (36)h | 19 (35) | 172 | 88 (51) | 55 (63) | |

| Cytogenetic subgroupsb | Cytogenetic subgroupsb | ||||||

| High hyperdiploidyc | 279 | 30 (11)h | 14 (47) | TAL1 rearrangementsi | 49 | 21 (43) | 12 (57) |

| ETV6-RUNX1 | 218 | 33 (15)g | 15 (45) | TLX3 rearrangementsj | 41 | 31 (76)h | 18 (58) |

| t(1;19)(q23;p13) | 25 | 10 (40)g | 2 (20) | LMO2 rearrangementsk | 23 | 9 (39) | 6 (67) |

| MLL translocationsd | 22 | 2 (9) | 1 (50) | MLL translocationsd | 11 | 2 (18) | 1 (50) |

| t(9;22)(q34;q11) | 19 | 11 (58)h | 1 (9)g | TLX1 abnormalitiesl | 9 | 8 (89)g | 4 (50) |

| iAMP21e | 19 | 5 (26) | 3 (60) | AF10-CALM | 9 | 4 (44) | 1 (25) |

| Normal karyotypef | 52 | 6 (12) | 6 (100)h | Normal karyotypef | 55 | 23 (42) | 18 (78) |

Data are missing for 86 patients.

Patients with each specific abnormality were compared with either all other patients with successful cytogenetics or those who tested negative for that particular abnormality by FISH, as appropriate.

Karyotypes with 51 to 65 chromosomes.

Patients positive by FISH or with an established translocation by G-banded analysis.

Intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21.

A normal karyotype was defined as the presence of 20 or more normal metaphases and the absence of any cytogenetically visible abnormality or any abnormality detected by FISH.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Involvement of TAL1 was confirmed by FISH in all cases. Group comprised SIL-TAL1 (n = 43), t(1;14)(p32;q11)/TAL1-TRA@/TRD@ (n = 5), and t(1;14)(p32;q32)/TAL1-IGH@ (n = 1).

Involvement of TLX3 (HOX11L2) was confirmed by FISH in all cases. In 33 cases, BCL11B was also confirmed to be involved, ie, t(5;14)(q35;q32).

Involvement of LMO2 was confirmed by FISH in all cases and the partner gene was identified in 20 cases: t(11;14)(p13;q11)/LMO2-TRA@/TRD@ (n = 15), t(7;11)(q34;p13)/LMO2-TRB@ (n = 3), t(7;11)(p15;p13)/LMO2-TRG@ (n = 1), and t(11;14)(p13;q32)/LMO2-BCL11B (n = 1).

Involvement of TLX1 (HOX11) was confirmed by FISH in all cases and the partner gene was identified in 7 cases: t(10;14)(q24;q11)/TLX1-TRA@/TRD@ (n = 4) and t(7;10)(q36;q24)/TLX1-TRB@ (n = 3).

The incidence of CDKN2A deletions at relapse was slightly higher than that seen at diagnosis among BCP-ALL patients, although the difference was not statistically significantly: 21 of 69 (30%) versus 180 of 864 (21%; P = .06). The relapse cohort comprised only 8 T-ALL patients of which only 2 (25%) harbored a CDKN2A deletion; however, both were biallelic. Among 44 patients where we were able to assess CDKN2A status at both diagnosis and relapse by FISH, SNPA, or aCGH, 28 (64%) patients had normal CDKN2A at both time points. The remaining 16 (36%) patients showed retention (n = 9, 20%) or gain (n = 7, 16%) of a CDKN2A deletion or 9p CNN LOH between diagnosis and relapse. The 7 CDKN2A abnormalities acquired at relapse composed: 2 monoallelic deletions, 4 biallelic deletions, and 1 CNN LOH between 9p21.1 and the telomere. These 7 patients did not have any remarkable features with respect to age at diagnosis, WCC, immunophenotype, karyotype, or time to relapse (data not shown). Interestingly, 6 (86%) of these patients were male and 3 relapses involved the testes as well as the bone marrow.

Discussion

This is the first study to use 5 separate technologies to assess the principal mode of CDKN2A inactivation in childhood ALL. We found that CDKN2A mutations were rare in this disease, which agrees with most21-24 but not all previous studies.12,20 We found only one mutation that was a C to T substitution in exon 2, which produced an amino acid change from histidine to tyrosine at codon 83 (H83Y) and has been shown to be defective in inducing cell- cycle arrest.35 This H83Y mutation has not previously been reported in leukemia but has been detected in bladder and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.36,37 Despite screening more than 100 samples for hypermethylation of the CDKN2A promoter, we found partial methylation in only one diagnostic sample. Two previous studies of a similar size found CDKN2A methylation in 7%16 and 32%.18 Several much smaller studies (< 30 patients) have reported equally variable levels of methylation. However, it has been suggested recently that CDKN2A hypermethylation is not a disease-specific event because it has been observed in the mononuclear cells from normal participants.38 In contrast, we have demonstrated that genomic deletion of CDKN2A is substantially more prevalent in childhood ALL (20% in BCP-ALL and 50% in T-ALL) than either mutation or methylation. As the cohorts we screened for mutation and methylation excluded cases with biallelic deletion of CDKN2A, our figures are underestimates of the true incidence. We assessed genomic deletion by SNPA, aCGH, and FISH and found a very high degree of concordance between the 3 techniques, with only a handful of deletions detected by aCGH, which were below the resolution of FISH. The apparent difference in detection rate between SNPA (17%) and aCGH (32%) is the result of the fact that specific cytogenetic subgroups were selected for aCGH analysis. Therefore, we concluded that genomic deletion is the principal mode of CDKN2A inactivation in childhood ALL and that FISH is a reliable and accurate method for detecting these deletions.

To accurately assess the incidence of monoallelic and biallelic deletions in childhood ALL, we screened 2 large and unbiased cohorts of BCP-ALL and T-ALL patients by FISH. More than 200 patients were screened with more than one FISH probe, and there was a high degree of concordance. As expected, the smaller home-grown WRGL probe detected a handful of smaller deletions that were below the resolution of the commercial probes. Despite these discrepancies and those detected comparing aCGH and FISH, the numbers of patients involved were small and not sufficient to affect the subsequent analyses. In agreement with previous large studies,13,39,40 we found that the incidence of CDKN2A deletions was significantly higher among T-ALL patients compared with BCP-ALL patients, which included the proportion of biallelic deletions. Among BCP-ALL patients, we found a frequency of CDKN2A deletions of 21%, which was the same as Kawamata et al41 (21%) but lower than Bertin et al13 (31%) and Mullighan et al39 (34%). We found that 50% T-ALL harbored a CDKN2A deletion, a frequency substantially lower than that reported by Bertin et al13 (78%), Mullighan et al39 (72%), and Kawamata et al41 (78%). These differences are probably the result of variation in the underlying patient cohort with respect to age and WCC rather than the technique used. First, evidence from our study and the study by Usvasalo et al40 indicated that the majority of CDKN2A deletions are detectable by FISH. Second, data from this study and the study by Mirebeau et al42 showed that the frequency of CDKN2A deletions varied according to age and presenting WCC. Our study included more than 1200 patients (more than the combined total from the 3 main previous studies), thereby minimizing the effect of any slight variations in age or WCC distribution.

The number of cases included in our study was sufficiently large to systematically address the relationship between CDKN2A deletions and specific cytogenetic subgroups. CDKN2A deletions were less frequent in patients with high hyperdiploidy and the ETV6-RUNX1 fusion compared with those without these abnormalities. We found a similar incidence of deletions among high hyperdiploidy patients as Mirebeau et al,42 but these authors found that more than a third of ETV6-RUNX1 patients had a deletion. However, their result was based on fewer than 50 patients, whereas more than 200 ETV6-RUNX1-positive patients were included in this study. In addition, we observed a higher incidence of CDKN2A deletions among patients with t(1;19) and t(9;22). Although patients with a MLL translocation were divided between the BCP-ALL and T-ALL cohorts, it was clear that the incidence of CDKN2A deletions was rare in this subgroup with only 4 of 33 (12%) showing evidence of a deletion. Interestingly, the incidence also varied within the T-ALL cohort where patients with TLX3 or TLX1 rearrangements had a high incidence of deletion. In a separate study, we have recently observed a strong correlation between the presence of t(6;14)(p22;q32)/IGH@-ID4 and a monoallelic CDKN2A deletion.43

As in previous studies, we observed both monoallelic and biallelic CDKN2A deletions and found that the latter were more prevalent in T-ALL.13,40,42 Interestingly, within the BCP-ALL and T-ALL cohorts, the proportion of biallelic deletions did not vary by age, WCC, or cytogenetic subgroup, with the exception of t(9;22) and normal karyotypes. However, these observations were based on relatively few cases. In our cohort, biallelic deletions composed one large and one much smaller deletion. A recent aCGH/FISH study by Usvasalo et al,40 which focused on older children and adolescents, observed a similar architecture.

The use of SNP arrays allowed the identification of CNN LOH, a phenomenon that has recently been associated with malignancy, including ALL.41,44-46 Previous studies have shown that this genetic mechanism is associated with the presence of homozygous mutations: JAK2 in myeloproliferative diseases, PTCH in basal cell carcinomas, and FLT3 in AML.44,47,48 None of our CDKN2A CNN LOH cases was associated with deletion or methylation, and only one had a CDKN2A mutation. However, the region of CNN LOH always encompassed numerous other genes and in half of the cases extended to the whole chromosome, indicating the probable involvement of other candidate genes such as PAX5 at 9p13.2.39 Recently, Kawamata et al41 identified a similar incidence of 9p/whole chromosome 9 CNN LOH (12%) among children with ALL. However, Kawamata et al found an association between 9p CNN LOH and CDKN2A deletion but not with whole chromosome 9 CNN LOH. Interestingly, both studies showed a strong association between 9p CNN LOH and high hyperdiploidy, and this was particularly strong for cases with whole chromosome 9 CNN LOH. Therefore, it is not surprising that chromosome 9 is rarely gained in children with high hyperdiploidy.49

The literature is divided as to the prognostic relevance of CDKN2A deletions in childhood ALL, with some studies indicating an adverse effect50-54 whereas others show no effect.42,55,56 These studies followed several cytogenetic based reports suggesting an adverse outcome for patients with a cytogenetically visible 9p abnormality.57,58 The majority of patients in this study are being treated on an ongoing clinical trial; hence, we are unable to present survival analysis. However, our results are highly relevant to this debate on prognosis. We have demonstrated unequivocally that the frequency of CDKN2A deletions is unevenly distributed across distinct cytogenetic subgroups; therefore, any study assessing their prognostic impact must incorporate analysis stratified by cytogenetics. It is possible that the inconsistent results of previous studies with respect to the prognostic relevance of CDKN2A deletions are the result of the variable frequency of deletions by cytogenetic subgroup. However, it is also possible that CDKN2A deletions do not represent a true independent prognostic factor. A large study incorporating cytogenetics and the accurate determination of CDKN2A deletion is required to address this important issue. We did not observe any difference in the incidence of CDKN2A deletion between diagnosis and relapse; but given the small number of patients in our series, a larger study will be required to definitely answer this question. However, we would not draw the same conclusion for T-ALL where the frequency of CDKN2A deletions is higher, less variable by genetic subtype, and the subject of fewer analyses.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the principal mode of CDKN2A inactivation in childhood ALL is by genomic deletion and that FISH is an efficient detection method. Moreover, we have established that the frequency of deletions varies considerably by genetic subtype, especially within BCP-ALL where this variation probably accounts for discrepant reports as to its prognostic relevance. The architecture of biallelic deletions and the observation of large areas of 9p with disease-specific CNN LOH implicate other genes within this region, which are probably important, both for maintaining and initiating the leukemia phenotype.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all member laboratories of the United Kingdom Cancer Cytogenetics Group for providing cytogenetic results, cell suspensions, and/or cDNA (a full list of laboratories is available on request) and the Clinical Trial Service Unit (University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom) for providing clinical data. The authors also thank Drs John Crolla and Fiona Ross and their teams at Wessex Regional Genetics Laboratory (Salisbury, United Kingdom) for the growing and preparation of the home-grown CDKN2A and CTB-25B13 FISH probes. This study could not have been performed without the dedication of the Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group Leukaemia and Lymphoma Division (previously known as the UK Childhood Leukaemia Working Party) and their members, who designed and coordinated the clinical trials through which these patients were identified and on which they were treated.

Authorship

Contribution: S.S. performed mutation, methylation, and SNP analysis; A.V.M. conducted statistical analyses; J.A.E.I., M.C.C., and L.M. supervised mutation, methylation, and SNP studies; J.C.S. and H.P. performed array CGH studies; Z.J.K., K.E.B., S.L.W., and A.R.M.S. conducted FISH tests; N.P.B. provided cytogenetic and FISH data; S.B. contributed patient samples and data; A.G.H., C.J.H., J.A.E.I., and A.V.M. initiated and designed the study; A.V.M. wrote the manuscript with contributions from S.S., J.A.E.I., J.C.S., C.J.H., and A.G.H.; and all authors critically reviewed the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anthony V. Moorman, Leukaemia Research Cytogenetics Group, Northern Institute for Cancer Research, Newcastle University, Level 5, Sir James Spence Institute, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Queen Victoria Road, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 4LP, United Kingdom; e-mail: anthony.moorman@ncl.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal