Abstract

Mice lacking both the p110γ and p110δ isoforms display severe impairment of thymocyte development. Here, we show that this phenotype is recapitulated in p110γ−/−/p110δD910A/D910A (p110γKOδD910A) mice where the p110δ isoform has been inactivated by a point mutation. Moreover, we have examined the pathological consequences of the p110γδ deficiency, which include profound T-cell lymphopenia, T-cell and eosinophil infiltration of mucosal organs, elevated IgE levels, and a skewing toward Th2 immune responses. Using small-molecule selective inhibitors, we demonstrated that in mature T cells, p110δ, but not p110γ, controls Th1 and Th2 cytokine secretion. Thus, the pathology in the p110γδ-deficient mice is likely to be secondary to a developmental block in the thymus that leads to lymphopenia-associated inflammatory responses.

Introduction

Class I phosphoinositide-3-kinases (PI3Ks) comprise a family of lipid kinases that phosphorylate the 3-OH of phosphatidylinositol(4,5)P2 to generate PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 that mediates many important functions such as proliferation, differentiation, survival, and migration.1,2 The class I PI3K family consists of IA and IB subclasses. The class IA PI3K includes the p110α, p110β, and p110δ catalytic subunits, each of which is associated with a p85 regulatory subunit and is regulated by tyrosine kinase signaling.3,4 The class IB PI3K includes only one catalytic subunit p110γ, which is associated with a p101 or p84/p87PIKAP regulatory subunit and is regulated by G-protein–coupled receptor signaling.5,6 Unlike p110α and p110β, which are ubiquitously expressed, the p110γ and p110δ isoforms are predominantly expressed in the hematopoietic system,7 suggesting a more specific and important role of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ in leukocyte development and function.

Mice with deletion or kinase inactivation of p110γ show impaired neutrophil and macrophage migration, mast cell degranulation, and a mild defect in thymocyte development.8-13 Mice with deletion or kinase inactivation of p110δ show impaired neutrophil chemotaxis, mast cell degranulation upon IgE receptor cross-linking, and compromised B-cell development and activation.14-18 T-cell development is apparently unaffected, however, T-cell proliferation, Th1 and Th2 differentiation, and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell activity are compromised in p110δ-deficient mice.17,19,20 The multiple roles of p110γ and p110δ in various immune cells have encouraged the development of small-molecule inhibitors of p110γ or p110δ, alone or in combination, in treating immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.14,21-24

Immature T cells developing in the thymus pass through a number of selection check points. During the β-selection step, T cells that express a cell surface TCRβ chain in conjunction with a pre-Tα chain receive a signal to develop into CD4+CD8+ T cells. This selection depends on functional TCR signaling and is blocked in mice lacking Lck, ZAP-70, LAT, or SLP-76.25-29 Recently, 2 groups have reported the importance of p110γ and p110δ cooperativity at this selection step as well. T cells from p110γδ double-knockout (p110γδ−/−) mice are substantially blocked at the β-selection step, resulting in a dramatic reduction in CD4+CD8+ T cells in the thymus.30,31 Impaired signaling by the pre-TCR in p110γδ−/− mice was correlated with reduced phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 and increased expression of Bim, suggesting defects in cell growth and survival at this critical selection stage.30 Consequently, peripheral T-cell numbers are dramatically reduced in blood, spleen, and lymph nodes of p110γδ−/− mice. In addition, most peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express high levels of CD44high, but low levels of CD62L, CD25, and CD69.30 This pattern of expression is typical for lymphopenic mice.32

Under condition of lymphopenia-induced homeostatic expansion, T-cell clones that bear high ability to respond to homeostatic factors, such as self-peptide/MHC, tend to dominate the repertoire.33 Therefore, lymphopenia is frequently linked to, although not always causes, autoimmunity.34 A secondary factor is necessary to induce autoimmune diseases, including dysregulated regulatory T-cell function or the presence of local tissue inflammation.

Because lymphopenia and compensatory homeostatic expansion tend to create autoimmunity,34 we sought to investigate the pathological consequences of lymphopenia caused by combined p110γ and p110δ deficiency. In addition, we sought to determine whether p110γ and p110δ act cooperatively to regulate mature T-cell responses.

Materials and methods

Animals

p110γ KO and p110δD910A/D910A mice have been described previously.8,17 p110γ KO and p110δD910AD910A mice were backcrossed with C57Bl/6 for 7 or 6 generations, respectively, and intercrossed to generate homozygous single- or double-mutant mice. Severe-combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (L'Arbresle, France). Unless stated, we used 6- to 10-week-old mice in all experiments. Breeding and maintenance of animals were according to the regulations of the Swiss Veterinary Authority (Office Vétérinaire Cantonal).

Histology and immunofluorescent staining

Organs were removed and 4-μm sections were prepared from paraffin- or cryostat-embedded blocks and were stained with hematoxylin & eosin or May-Grünwald-Giemsa (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) or PE-conjugated anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) antibodies as indicated. Sections were examined with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope and photographs taken with a Zeiss Axiocam camera (Carl Zeiss SA, Zurich, Switzerland) and Nikon ACT-1 software (version 2.12).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis

With the exception of anti-GITR and anti-FoxP3 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), all other antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen: anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-CD44, anti-CD3, anti-CD28, anti-B220, anti-CD45. Cells were analyzed by the FACSCalibur and CellQuest software (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA).

ELISA for immunoglobulin isotype detection

Serum concentrations of IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgM, and IgA were determined by mouse immunoglobulin isotyping enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit, and serum IgE concentrations were measured with IgE-specific ELISA (BD Pharmingen).

T-cell proliferation

T cells negatively purified with anti–MHC-class II magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) were incubated in 96-well plates precoated with 10 μg/mL antimouse CD3ϵ mAb (BD Pharmingen) with or without 10 μg/mL antimouse CD28 (BD Pharmingen) for 48 hours. For measuring T-cell proliferation, plates were pulsed with [3H]-thymidine at 1 μCi (0.037 MBq)/well for the last 6 hours. Cytometric bead array for mouse Th1/Th2 cytokines (BD Pharmingen) was used to detect cytokines from the supernatant.

T regulatory cell (Treg) suppression assay

T cells negatively purified with anti–MHC-class II magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) were further sorted by FACSAria (BD Bioscience) to obtain CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− cells. CD4+CD25− cells (5 × 104) and/or CD4+CD25+ cells (5 × 104) were incubated in 96-well plates with 5 × 104 T-cell–depleted and mitomycin-treated splenocytes and 1 μg/mL CD3ϵ mAb (BD Pharmingen) for 72 hours for measuring proliferation and cytokine release. For measuring T-cell proliferation, plates were pulsed with [3H]-thymidine at 1 μCi (0.037 MBq)/well for the last 6 hours. Cytometric bead array for mouse Th1/Th2 cytokines (BD Pharmingen) was used to detect cytokines from the supernatant.

Mixed leukocyte reaction

T cells were purified with Pan-T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). T cells (1 × 105) were cultured with 2.5 × 105, 5 × 105, or 10 × 105 mitomycin C–treated T-depleted cells from spleen as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) for 48 hours. Plates were pulsed with [3H]-thymidine for the last 6 hours.

Cell isolation from organs

Mice were perfused with PBS and salivary glands and stomach were removed. Stomach contents were washed out with PBS and organs were incubated in cell culture medium RPMI-1640 with collagenase IV (8 mg/mL) (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) and 1% DNAse for 1 hour at 37°C. Organs were then passed through a 70-μm nylon mesh to obtain a single-cell suspension for further analysis.

PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ inhibitors

Results

Severe lymphopenia in p110γKOδD910A mice

We crossed p110γ−/− mice and p110δD910A/D910A mice to generate p110γ−/−p110δD910A/D910A double-mutant mice (hereafter referred to as p110γKOδD910A mice).8,17 Similar to mice lacking both p110γ and p110δ,30,31 p110γKOδD910A mice displayed defective thymocyte development, demonstrated as thymus atrophy, reduced thymocyte numbers, loss of cortex-medulla organization, reduced cellularity especially of CD4+8+ double-positive (DP) cells, and CD4+8− and CD4−8+ single-positive (SP) cells, increased CD4−8− double-negative 3 (DN3)/DN4 ratio, and high level of CD25 expression on DN3 cells (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Thus, our results are in line with previous reports that PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ cooperativity is critical for thymocyte development.

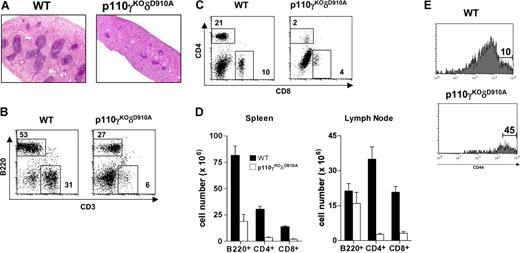

As a consequence of the blocked thymocyte development, p110γKOδD910A mice displayed spleen atrophy (Figure 1). Very few lymphoid follicles were observed in the white pulp of the p110γKOδD910A mice (Figure 1A). Both B220+ and CD3+ cell (including CD4+ and CD8+ cell) numbers were dramatically reduced (Figure 1B-D), and most CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressed high levels of CD44 (Figure 1E and data not shown). Whereas the reduction in B-cell numbers was comparable with that observed in p110δD910A/D910A mice, the dramatically reduced proportion of T cells and the high expression of CD44 was observed only in p110γKOδD910A mice.

Lymphopenia in p110γKOδD910A mice. (A) H&E staining of spleen (4×/0.12 objective lens). (B-E) Flow cytometry analysis. (B) B220 and CD3 profile of spleen. (C) CD4 and CD8 profile of spleen. (D) Numbers of B220+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells from spleen and lymph nodes. (E) CD44 profile gated on CD4+ cells from spleen. Data are from 6 mice in each group (± SEM). Numbers inside panels B and C indicate percentage of gated cells in total splenocytes; numbers in panel E, percentage of gated cells in CD4+ splenocytes.

Lymphopenia in p110γKOδD910A mice. (A) H&E staining of spleen (4×/0.12 objective lens). (B-E) Flow cytometry analysis. (B) B220 and CD3 profile of spleen. (C) CD4 and CD8 profile of spleen. (D) Numbers of B220+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells from spleen and lymph nodes. (E) CD44 profile gated on CD4+ cells from spleen. Data are from 6 mice in each group (± SEM). Numbers inside panels B and C indicate percentage of gated cells in total splenocytes; numbers in panel E, percentage of gated cells in CD4+ splenocytes.

Markedly reduced immunoglobulin (Ig) production and relatively increased type 2 Ig isotype level in p110γKOδD910A mice

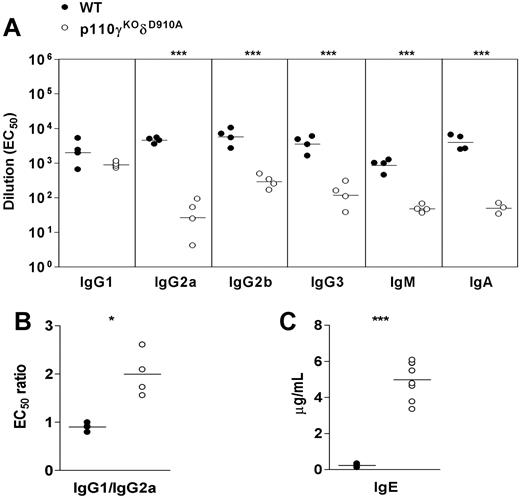

We tested serum levels of different immunoglobulin isotypes of mice at ages between 2 weeks to 12 weeks and compared them with their littermates' levels. Compared with WT mice, p110γKOδD910A mice produced less IgG2a, IgG2b, IgM, and IgA; however, IgG1 levels were normal, which resulted in increased IgG1/IgG2a ratio (Figure 2A,B). Unexpectedly, the amount of IgE was 10 to 20 times higher in the serum of p110γKOδD910A mice (Figure 2C). These data indicate that type 2 immunity-associated Ig isotypes are preferentially formed in p110γKOδD910A mice despite a severe defect in B-cell development and overall Ig production.

Altered immunoglobulin production in p110γKOδD910A mice. (A) Ig isotype level. (B) IgG1/IgG2a ratio and (C) IgE level in serum taken from WT and p110γKOδD910A mice at 9 to 10 weeks of age. Each dot represents one individual mouse (representative of at least 3 experiments). Horizontal lines indicate mean value of each group.

Altered immunoglobulin production in p110γKOδD910A mice. (A) Ig isotype level. (B) IgG1/IgG2a ratio and (C) IgE level in serum taken from WT and p110γKOδD910A mice at 9 to 10 weeks of age. Each dot represents one individual mouse (representative of at least 3 experiments). Horizontal lines indicate mean value of each group.

Increased peripheral T-cell proliferation and Th2 cytokine production in p110γKOδD910A mice

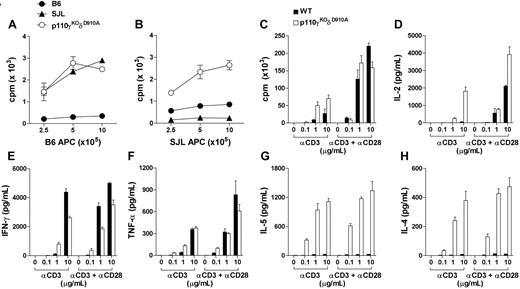

It is well established that T cells in lymphopenic mice undergo excessive expansion and acquire effector/memory-like phenotype.35 Indeed, in contrast to the single isoform–deficient mice that retained normal responses,8,17 p110γKOδD910A T cells proliferated rigorously to both allogeneic (H-2s) and self-MHC (H-2b) in mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) assay (Figure 3A,B). In addition, p110γKOδD910A T cells exhibited increased proliferation as well as IL-2 release upon α-CD3 stimulation, but were comparable with WT T cells in response to α-CD3/α-CD28 activation (Figure 3C,D). p110γKOδD910A T cells produced marked increase of Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-4 and reduced Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and a comparable amount of TNF-α to levels secreted by WT T cells (Figure 3E-H). Therefore, the substantially augmented T-cell response in lymphopenic p110γKOδD910A mice was skewed toward Th2-associated cytokines.

Altered peripheral T-cell function in p110γKOδD910A mice. (A-B) Purified T cells were cultured with purified and mitomycin C–treated T-cell–depleted splenocytes from WT (B6) or SJL mice for 48 hours. 3H-thymidine (TdR) was added at 42 hours. (C-H) Purified T cells from lymph nodes of WT or p110γKOδD910A mice were cultured with plate-coated α-CD3 (at indicated concentrations, μg/mL) with or without α-CD28 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hours. Proliferation was measured as in panel A and cytokines from supernatant were measured by cytometric bead arrays. Data represent at least 2 experiments with triplicates for each sample (± SEM).

Altered peripheral T-cell function in p110γKOδD910A mice. (A-B) Purified T cells were cultured with purified and mitomycin C–treated T-cell–depleted splenocytes from WT (B6) or SJL mice for 48 hours. 3H-thymidine (TdR) was added at 42 hours. (C-H) Purified T cells from lymph nodes of WT or p110γKOδD910A mice were cultured with plate-coated α-CD3 (at indicated concentrations, μg/mL) with or without α-CD28 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hours. Proliferation was measured as in panel A and cytokines from supernatant were measured by cytometric bead arrays. Data represent at least 2 experiments with triplicates for each sample (± SEM).

Partially impaired suppressing function of CD4+CD25+ cells in p110γKOδD910A mice

CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells (Tregs) play important roles in maintaining T-cell homeostasis and modulating immune responses.36-38 Foxp3 is a master control gene for the development and function of natural CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, and its expression serves as a specific and stable marker of Tregs.39 In contrast, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein (GITR), expressed on the surface of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, negatively regulates their immunosuppressive function.40,41 In p110δD910A/D910 mice, there are increased Tregs found in the thymus, whereas the numbers of Tregs are reduced in the peripheral lymphoid organs.20 Similarly, the percentage of CD4+Foxp3+ cells in p110γKOδD910A mice was 2 to 3 times higher than WT in thymus, however, in the lymph nodes the proportions of Tregs were increased, while they were comparable in the spleen (Figure 4A). The relative expression levels of Foxp3 and GITR were reduced in thymus but relatively normal in spleen and lymph nodes of p110γKOδD910A mice (Figure 4B,C). p110δD910A Tregs show impaired suppression in in vitro assays.20 We measured the suppression function of the CD4+CD25+ cells isolated from WT and p110γKOδD910A mice. Purified CD4+CD25− and/or CD4+CD25+ cells were cultured in vitro in the presence of WT APCs and α-CD3. WT and p110γKOδD910A CD4+CD25− T cells proliferated to a similar extent, but in both cases the Tregs were refractory to proliferation (Figure 4D first and second bar groups). When cocultured with WT CD4+CD25− cells, WT CD4+CD25+ Tregs markedly suppressed the proliferation and cytokine production, but p110γKOδD910A CD4+CD25+ Tregs failed to do so (Figure 4D-F third bar group). However, WT and p110γKOδD910A CD4+CD25+ Tregs suppressed the proliferation and cytokine production of p110γKOδD910A CD4+CD25− cells to a similar extent (Figure 4D-F fourth bar group). Taken together, p110γKOδD910A mice harbored higher proportion of CD4+CD25+ Tregs with reduced Foxp3 and GITR expression that still efficiently suppressed self but not WT CD4+CD25− cell activity.

Partially impaired CD4+CD25+ Treg function in p110γKOδD910A mice. (A-C) Cells from thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes of WT and p110γKOδD910A mice were stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against surface marker CD4, et al. (A). Percentage of Foxp3+ cells gated from CD4+CD8− cells in thymus or CD4+ cells in spleen and lymph nodes. (B,C) Mean fluorescent intensity of Foxp3 and GITR on CD4+CD8−CD25+ cells in thymus or CD4+CD25+ cells in spleen and lymph nodes. (D) Purified 5 × 104 CD4+CD25+ and/or CD4+CD25− cells from WT or p110γKOδD910A (−/−) mice were incubated with T-cell–depleted and mitomycin-treated splenocytes and 1 μg/mL α-CD3 in 96-well plate for 72 hours for measuring proliferation. (E,F) TNF-α and Il-4 produced by T cells shown in panel D. Data represent at least 2 experiments with triplicates for each sample (± SEM). ■ represents WT; □, p110γKOδD910A.

Partially impaired CD4+CD25+ Treg function in p110γKOδD910A mice. (A-C) Cells from thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes of WT and p110γKOδD910A mice were stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against surface marker CD4, et al. (A). Percentage of Foxp3+ cells gated from CD4+CD8− cells in thymus or CD4+ cells in spleen and lymph nodes. (B,C) Mean fluorescent intensity of Foxp3 and GITR on CD4+CD8−CD25+ cells in thymus or CD4+CD25+ cells in spleen and lymph nodes. (D) Purified 5 × 104 CD4+CD25+ and/or CD4+CD25− cells from WT or p110γKOδD910A (−/−) mice were incubated with T-cell–depleted and mitomycin-treated splenocytes and 1 μg/mL α-CD3 in 96-well plate for 72 hours for measuring proliferation. (E,F) TNF-α and Il-4 produced by T cells shown in panel D. Data represent at least 2 experiments with triplicates for each sample (± SEM). ■ represents WT; □, p110γKOδD910A.

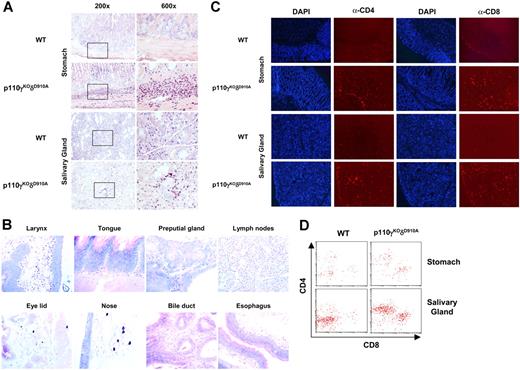

Eosinophil- and T-cell–dominated inflammation in multiple organs but undetectable circulating autoantibodies in p110γKOδD910A mice

By histologic examination, we found that all p110γKOδD910A mice (n = 12) demonstrated gastritis and sialadenitis with approximately 80% to 90% of eosinophil and 10% of neutrophil infiltrates in submucosa of stomach and interstitial tissue of salivary glands (Figure 5A). Eosinophilic inflammation was also observed in other organs of different individuals to various extents (Table 1; Figure 5B). Predominant amount of CCR3+ cells (data not shown), and to a lesser extent, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, was also detected in the lesions (Figure 5C). Accordingly, higher percentage of CD45high CD4+ or CD45high CD8+ cells was recovered from stomach and salivary glands (Figure 5D). Other organs, such as pancreas, kidney, lung, liver, and heart were normal (data not shown). No sign of inflammation in any of the organs examined was observed in the WT control mice (n = 12). No parasite was found in the tissues in both strains. Augmented levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, and MCP-1 were also detected in p110γKOδD910A serum (Figure S2). To examine if there are circulating tissue-specific autoantibodies, we probed stomach and salivary gland sections from SCID.B6 mice with serum from p110γKOδD910A, WT, and lupus-like MRL.lpr/lpr mice (as positive control) and revealed the Ab isotypes with secondary α-IgG and α-IgM fluorescence-conjugated Abs. Both IgG and IgM autoantibodies were detected from MRL.lpr/lpr (1:50 dilution) but not WT (1:50 dilution) or p110γKOδD910A serum (even up to 1:5 dilution when background staining could be detected from WT serum) (Figure S3). Similarly, no signal was detected with α-IgE FITC-conjugated Ab (data not shown). Thus, eosinophils and T cells but not autoantibodies likely mediated multiple organ inflammation in the mucosal tissues of p110γKOδD910A mice.

Inflammation in multiple organs. (A) Stomach and salivary gland from WT and p110γKOδD910A (−/−) mice stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa. (B) Organs from p110γKOδD910A (−/−) mice stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa (40×/0.75 objective). (C) Stomach and salivary gland from WT and p110γKOδD910A (−/−) mice stained with DAPI and PE conjugated α-CD4 or α-CD8 Ab (100×/1.30 oil objective). (D) Flow cytometry analysis of cells from stomach and salivary gland of WT and p110γKOδD910A mice (n = 4).

Inflammation in multiple organs. (A) Stomach and salivary gland from WT and p110γKOδD910A (−/−) mice stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa. (B) Organs from p110γKOδD910A (−/−) mice stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa (40×/0.75 objective). (C) Stomach and salivary gland from WT and p110γKOδD910A (−/−) mice stained with DAPI and PE conjugated α-CD4 or α-CD8 Ab (100×/1.30 oil objective). (D) Flow cytometry analysis of cells from stomach and salivary gland of WT and p110γKOδD910A mice (n = 4).

Hematology and histology of p110γKOδD910A mice

| Phenotype/parameter . | Frequency . | Individual mouse . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 . | F2 . | M1 . | M2 . | ||

| Hematology | |||||

| Neutrophilia | 4/4 | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Eosinophilia | 4/4 | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Lymphocytopenia | 4/4 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Thrombocytosis | 4/4 | + | + | + | + |

| Erythrocytosis | 2/4 | + | – | – | + |

| Erythrocytopenia | 1/4 | – | – | + | – |

| Histology | |||||

| Lymphoid organs | |||||

| Thymus, diffuse lymphoid atrophy | 4/4 | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| Spleen, diffuse lymphoid depletion | 4/4 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Spleen, extramedullary hematopoiesis | 4/4 | + | +++ | + | ++ |

| Bone marrow, granulocytic hyperplasia | 4/4 | + | + | + | + |

| Small intestines, Peyer patches | 2/4 | Absent | Remnants | Remnants | Absent |

| Large intestines, Peyer patches | 4/4 | Remnants | Remnants | Remnants | Remnants |

| Inflammation | |||||

| Gastritis, acute and diffuse | 4/4 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Sialoadenitis submandibular, acute & focally extensive | 3/4 | + | – | +++ | +++ |

| Sialoadenitis, parotid, acute & focally extensive | 2/4 | – | +++ | – | +++ |

| Enteritis, acute & diffuse | 1/4 | – | – | –/+ | – |

| Laryngitis, acute | 1/4 | – | + | – | – |

| Glossitis, acute | 2/4 | – | + | – | –/+ |

| Blepharitis, acute | 1/4 | – | – | –/+ | – |

| Rhinitis | 1/4 | – | – | –/+ | – |

| Cholecystis | 1/4 | – | – | – | –/+ |

| Esophagitis | 1/4 | – | – | – | –/+ |

| Lymphadenitis (submandibular), acute | 1/4 | – | – | – | +++ |

| Epididymitis, chronic & active | 1/4 | – | – | – | +++ |

| Posthitis, acute | 1/4 | – | – | – | + |

| Phenotype/parameter . | Frequency . | Individual mouse . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 . | F2 . | M1 . | M2 . | ||

| Hematology | |||||

| Neutrophilia | 4/4 | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Eosinophilia | 4/4 | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Lymphocytopenia | 4/4 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Thrombocytosis | 4/4 | + | + | + | + |

| Erythrocytosis | 2/4 | + | – | – | + |

| Erythrocytopenia | 1/4 | – | – | + | – |

| Histology | |||||

| Lymphoid organs | |||||

| Thymus, diffuse lymphoid atrophy | 4/4 | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| Spleen, diffuse lymphoid depletion | 4/4 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Spleen, extramedullary hematopoiesis | 4/4 | + | +++ | + | ++ |

| Bone marrow, granulocytic hyperplasia | 4/4 | + | + | + | + |

| Small intestines, Peyer patches | 2/4 | Absent | Remnants | Remnants | Absent |

| Large intestines, Peyer patches | 4/4 | Remnants | Remnants | Remnants | Remnants |

| Inflammation | |||||

| Gastritis, acute and diffuse | 4/4 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Sialoadenitis submandibular, acute & focally extensive | 3/4 | + | – | +++ | +++ |

| Sialoadenitis, parotid, acute & focally extensive | 2/4 | – | +++ | – | +++ |

| Enteritis, acute & diffuse | 1/4 | – | – | –/+ | – |

| Laryngitis, acute | 1/4 | – | + | – | – |

| Glossitis, acute | 2/4 | – | + | – | –/+ |

| Blepharitis, acute | 1/4 | – | – | –/+ | – |

| Rhinitis | 1/4 | – | – | –/+ | – |

| Cholecystis | 1/4 | – | – | – | –/+ |

| Esophagitis | 1/4 | – | – | – | –/+ |

| Lymphadenitis (submandibular), acute | 1/4 | – | – | – | +++ |

| Epididymitis, chronic & active | 1/4 | – | – | – | +++ |

| Posthitis, acute | 1/4 | – | – | – | + |

+++ indicates marked; ++, moderate; +, mild; –, normal; and +/–, minimal.

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ does not promote Th2 cell switching in vitro

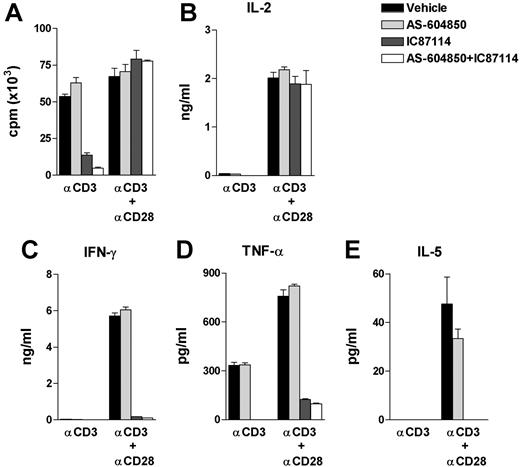

To assess the effect of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ isoforms on mature peripheral T cells, we treated naive T cells from WT lymph nodes with PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ selective inhibitors (AS-604850 and IC87114, respectively).15,21 In line with previously reported phenotype of p110δD910A T cells,17 PI3Kδ inhibitor IC87114 at concentration of 3 μM abrogated T-cell proliferation and IL-2 production in response to α-CD3 but not to α-CD3/α-CD28 stimulation (Figure 6A,B). In addition, IC87114 annulled Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and TNF-α as well as Th2 cytokine IL-5 production (note, the IL-5 level in cells treated with vehicle was minimal and IL-4 was not detectable under the current experimental condition) despite normal proliferation and IL-2 secretion upon α-CD3/α-CD28 activation (Figure 6A-E). In contrast, the PI3Kγ inhibitor AS-604850 did not exert any effect on any of the parameters examined, and when given together with IC87114, the inhibition effect was not further strengthened, indicating a negligible role of PI3Kγ in mature T-cell activation and cytokine secretion under these circumstances (Figure 6A-E). Neither IC87114 nor AS-604850 affected p110γKOδD910A T-cell response (data not shown), indicating that the inhibitors at the applied concentrations were specific. Thus, while p110γ and p110δ act synergistically during β-selection in the thymus, proliferation and cytokine responses by mature T cells are primarily p110δ dependent, with minimal input from p110γ.

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ of T-cell function. Purified WT lymph node T cells were cultured with plate-coated α-CD3 (at 10 μg/mL) with or without α-CD28 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hours. AS-604850 (10 μM) and/or IC87114 (3 μM) were preincubated with cells 20 minutes before stimulation. Data represent 4 experiments with triplicates for each sample (± sem). (A) Proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation as in Figure 3A. (B-E) Cytokines from supernatant were measured by cytometric bead arrays.

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ of T-cell function. Purified WT lymph node T cells were cultured with plate-coated α-CD3 (at 10 μg/mL) with or without α-CD28 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hours. AS-604850 (10 μM) and/or IC87114 (3 μM) were preincubated with cells 20 minutes before stimulation. Data represent 4 experiments with triplicates for each sample (± sem). (A) Proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation as in Figure 3A. (B-E) Cytokines from supernatant were measured by cytometric bead arrays.

Discussion

We demonstrated that p110γKOδD910A mice, which suffered from severe blockade of thymocyte development and lymphopenia, displayed homeostatic peripheral expansion of Th2 cells and type 2 inflammation in multiple organs. In contrast, blocking of the PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ isoforms with selective inhibitors did not promote Th2 cytokine production in vitro.

In p110γKOδD910A mice, the thymocyte output was severely compromised as evidenced by an approximately 90% reduction of CD4 SP and 60% reduction of CD8 SP thymocytes (Figure S1). This significant block in T-cell development most likely led to homeostatic expansion of the few T-cell clones that developed. Despite the prolific expansion of peripheral T cells, normal T-cell numbers were not restored, that is, approximately 10% of CD4+ and 15% of CD8+ cells were found in spleen and lymph nodes of p110γKOδD910A mice compared with WT controls (Figure 1). As in other lymphopenic hosts, p110γKOδD910A T cells responded rigorously to allogeneic as well as self-peptide/MHC complex (Figure 3).

p110γKOδD910A mice displayed strikingly skewed type 2 profile, including elevated IgG1/IgG2a ratio and significant amount of IgE in serum (Figure 2), increased secretion of IL-4 and IL-5 by peripheral T cells upon stimulation in vitro (Figure 3), and eosinophilic inflammation in multiple mucosal organs (Figure 5). Lymphopenia-induced T-cell expansion does not inevitably promote type 2 responses; on the contrary, it has been shown that Th1 T cells are preferably activated and dominantly proliferated during homeostatic expansion.42 The molecular mechanism underlying PI3K activity and Th cell differentiation is not fully understood. Akt/PKB, a downstream target of PI3K, has been shown to promote both Th1 and Th2 differentiation.43,44 In line with this, mice lacking p110δ activity display reduced Th1 and Th2-skewed phenotype in vitro and in vivo.19 On the other hand, Itk and Pdk1, also PI3K-dependent kinases, are required for Th2 differentiation.45,46 Ca2+ influx and NFAT activity upon activation of TCR have been shown to control Th cell differentiation.47 NFATc2-deficient mice display modestly increased Th2 cytokines and prolonged maintenance of IL-4 transcription,48 and NFATc2 and NFATc3 double-knockout mice produce extremely high amounts of IL-4, IL-5, and other Th2 cytokines as well as elevated serum IgG1 and IgE, leading to severe allergic inflammation.49 TCR-induced Ca2+ influx is dramatically reduced in p110γδ−/− CD4+ T cells, while only mildly affected in p110δ−/− CD4+ T cells.31 It is possible that the severity of impairment of TCR activation-mediated cytoplasmic Ca2+ mobilization affects activation of different components of NFAT activity, thereby influencing Th cell skewing. The reduced Ca2+ signaling in the absence of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ might reduce or diminish NFAT component activation, which in concert with the lymphoproliferative response, may lead to the profound Th2 skewing phenotype. In support of this hypothesis, mice harboring a LAT point mutant incapable of recruiting PLC-γ1 show largely impaired calcium flux and fail to activate NFATc1 and NFATc2 upon TCR cross-linking.50 Consequently, these mice develop tissue eosinophilia in lung, liver, and kidney due to massive Th2 development.50,51 The type 2 immune responses in p110γKOδD910A mice may have been further exacerbated by the reported capacity of p110δ to suppress class-switching recombination.52 The exaggerated type 2 cytokine and IgE and IgG1 resulted in overreacted immune response to otherwise innocuous bacterial flora in mucosa and organs directly connected to mucosa, hence further releasing proinflammatory cytokines and chemoattractants that recruited large amount of eosinophils (Figure 5). Further investigation using reconstitution models, such as transfer mutant T cells into immune-deficient host, should shed light on the underlying pathogenic mechanism in p110γKOδD910A mice.

In p110γKOδD910A mice, Treg function was partially impaired in assays with WT, but curiously not when p110γKOδD910A responder cells were included in the cultures (Figure 4D-F). On face value, this indicates that p110γKOδD910A T cells are more suppressible than WT T cells. Given the higher ratio of CD4+CD25+ to CD4+CD25− in peripheral lymphoid organs of p110γKOδD910Amice, these results suggested that the development and homeostatic expansion of Tregs was less affected than non-Treg population, and that the T-cell inflammation in p110γKOδD910A may not necessarily be a consequence of diminished Treg function. A relative increase in the frequency of Tregs has also been observed in other murine models as well as human lymphopenic individuals, resulting from more efficient homeostatic expansion of peripheral Tregs, which appears to outcompete the nonregulatory CD4+ T-cell pool (review see Krupica et al34 ).

Although the nature of the inflammation in p110γKOδD910A mice is not yet known, the fact that significant amount of IgE has also been detected in p110γδ−/− mice from another group (data not shown) suggests that it is not due to a specific SPF hygiene status in our laboratory. It is possible that increased responsiveness to local “normal” bacterial flora produces proinflammatory cytokines as the secondary factor that combined with severe lymphopenia in p110γKOδD910A mice to promote multiple mucosal organ inflammation, despite the absence of uncontrolled infection. This phenomenon, in some aspects, resembles human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndromes (IRISs), which is the most well-defined autoimmune syndrome associated with lymphopenia in humans.53 Although inflammation in IRIS patients often appears in tissues with previous infection, a T-cell–associated inflammatory response has been described.53 Moreover, profound lymphocyte expansion in draining lymph nodes and elevated serum IL-6 levels are also observed in patients with IRIS.54

p110γKOδD910A mice displayed similar defects in thymocyte development as well as similarly increased serum IgE level to that of p110γδ−/− mice. Our data show that PI3Kδ kinase activity, and not just protein per se, is required for cooperativity with PI3Kγ in thymocyte development, and likely, causing the pathological consequence in p110γKOδD910A mice. Thus, suppressing both PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ kinase activity might block certain immune-mediated diseases, but on the other hand, might risk imposing the danger of developing type 2 eosinophilic inflammatory diseases. However, the fact that selectively blocking PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ function with isoform-specific inhibitors reduced Th1 cytokine release without elevated Th2 response in vitro suggests that acute inhibition of p110δ and p110γ is not sufficient to direct Th2 differentiation in mature T cells.

In summary, mice lacking PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ function developed type 2 responses in immune system and corresponding eosinophilic inflammation in multiple mucosal organs. These symptoms were likely due to a defect in thymocyte development that results in severe lymphopenia-induced homeostatic lymphocyte expansion, and, probably, opportunistic infection enforced by lymphopenic condition. On the contrary, combined treatment of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ in adults, in whom the maintenance of the peripheral cell pool occurs primarily via thymic-independent pathway, the effect on thymocyte development will be negligible. On the other hand, the combined treatment will likely reduce Th1 without promoting Th2 response in vitro, although it remains to be determined under in vivo and pathologic conditions when Th1-Th2 balance is lost. Currently, the nature of the ligand(s) that operate PI3Kγ- and PI3Kδ-dependent mechanism in T cells is unknown.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by European Union Fifth Framework Program QLG1–2001-02171 (B.V. and C.R.).

We thank Domingo F. Barber and Ana C. Carrera for kindly providing us with serum from MRL/lpr mice. We thank Martin Turner for advice and providing us with serum from p110γ/δ−/− mice. We thank David Fruman for helpful discussion. We are grateful to all our colleagues for their kind and valuable support.

Authorship

Contribution: H.J. designed and performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; K.O and C.R. participated in designing the research and writing the paper; B.V. contributed vital reagent and participated in designing the research; F.R. and D.B.M. performed the research and participated in analyzing the data; C.W. participated in designing and performing the research and analyzing the data; A.B. and W.P. participated in performing the research; and E.H., M.P.W., T.R., and M.C. contributed vital reagents.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hong Ji, Target Research, Merck Serono S.A, Geneva Research Center, 9 chemin des Mines, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland; e-mail: hong.ji@merckserono.net.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal