Abstract

Here we report the identification of a novel human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B44–restricted minor histocompatibility antigen (mHA) with expression limited to hematopoietic cells. cDNA expression cloning studies demonstrated that the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitope of interest was encoded by a novel allelic splice variant of HMSD, hereafter designated as HMSD-v. The immunogenicity of the epitope was generated by differential protein expression due to alternative splicing, which was completely controlled by 1 intronic single-nucleotide polymorphism located in the consensus 5′ splice site adjacent to an exon. Both HMSD-v and HMSD transcripts were selectively expressed at higher levels in mature dendritic cells and primary leukemia cells, especially those of myeloid lineage. Engraftment of mHA+ myeloid leukemia stem cells in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID)/γcnull mice was completely inhibited by in vitro preincubation with the mHA-specific CTL clone, suggesting that this mHA is expressed on leukemic stem cells. The patient from whom the CTL clone was isolated demonstrated a significant increase of the mHA-specific T cells in posttransplantation peripheral blood, whereas mHA-specific T cells were undetectable in pretransplantation peripheral blood and in peripheral blood from his donor. These findings suggest that the HMSD–v–encoded mHA (designated ACC-6) could serve as a target antigen for immunotherapy against hematologic malignancies.

Introduction

Minor histocompatibility antigens (mHAs) are major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-bound peptides derived from cellular proteins encoded by polymorphic genes. Following human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), donor-recipient disparities in mHAs can induce a favorable graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect that is often associated with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).1-3 Significant efforts have been made to identify mHAs, particularly those specific for hematopoietic cells, since such mHAs are speculated to contribute to the GVL effect. The first report on the identification of a hematopoietic lineage-specific mHA, HA-1, was generated by the Goulmy group in 1998 (den Haan et al4 ) as a result of biochemical analysis of peptides eluted from HLA-A*0201 molecules. The only other mHAs with selective expression in hematopoietic cells described to date are HA-25 ; ACC-1 and ACC-26 ; and DRN-7,7 HB-1,8,9 and PANE1,10 the latter 2 of which are B-cell lineage-specific. Thus, identification of more mHAs should facilitate a better understanding of the biology of GVL and the development of effective immunotherapy to induce GVL reactions.

Immunogenicity of most autosomal mHAs identified to date results from single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that cause amino-acid substitutions within epitopes, leading to the differential display/recognition of peptides between HCT donor and recipient via several mechanisms: peptide binding to MHC observed in HA-1/A2-,4 HA-2-,5 and CTSH-encoded mHAs11 ; proteasomal cleavage in HA-312 ; peptide transport in HA-813 ; and altered recognition of MHC-peptide complex by cognate T cells in HB-1,8,9 HA-1/B60,14 ECGF1/B7,15 and SP110/A3.7 Other examples of mechanisms of mHA generation include differential protein expression due to a nonsense mutation in PANE110 and a frame-shift mutation in P2X5.16 UGT2B1717 is the sole example of differential protein expression due to gene deletion instead of an SNP. Because SNPs are scattered throughout the genome, it has been speculated that mHAs caused by those other than coding SNPs should be present.

In this study, we report the identification of a novel gene encoding an HLA-B44–restricted mHA that is recognized by the 2A12 cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) clone and selectively expressed in primary hematologic malignant cells, especially those of myeloid lineage, multiple myeloma (MM) cells, and normal mature dendritic cells (DCs). The antigenic peptide recognized by 2A12-CTL was encoded by a novel allelic splice variant of HMSD, hereafter designated as HMSD-v, due to an intronic SNP located in the consensus 5′ splice site adjacent to an exon. The leukemic stem cell (LSC) engraftment assay using severely immunodeficient mice demonstrated that the engraftment of primary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells was completely abolished by coincubation with the CTL clone before injection. These findings suggest that this novel mHA epitope may be an attractive therapeutic target for immunotherapy.

Patients, materials, and methods

Cell isolation and cell cultures

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Aichi Cancer Center. All blood or tissue samples were collected after written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. B-lymphoid cell lines (B-LCLs) were derived from donors, recipients, and healthy volunteers. B-LCLs and all cell lines of hematologic malignancy were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (referred to as complete medium). CD40 ligand-activated B (CD40-B) cells were generated as previously described.18

Immature DCs were generated by culturing CD14+ cells isolated from peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with 500 U/mL GM-CSF and 500 U/mL interleukin 4 (IL-4) in AIM-V medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 2 days, and then DCs were matured by cultivating the immature DCs for 2 additional days with 10 ng/mL IL-1β, 20 ng/mL IL-6, 10 ng/mL tissue necrosis factor α (TNF-α; all cytokines were from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and 1 μg/mL PGE2 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). When necessary, cells were retrovirally transduced with restricting HLA cDNA by a method described previously.18,19

Generation of CTL lines and clones

CTL lines were generated from PBMCs (∼106) obtained at day 197 after HCT by primary stimulation with irradiated (33 Gy) pre-HCT recipient PBMCs (∼106), thereafter stimulated weekly with irradiated (33 Gy) recipient CD40-B cells (2 × 106) twice in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% pooled human serum and 2 mM l-glutamine (referred to as CTL medium).11 IL-2 was added on days 1 and 5 after the second and third stimulation. CTL clones were isolated by standard limiting dilution and expanded in CTL medium as previously described.11,20

Chromium release assay

Target cells were labeled with 3.7 MBq of 51Cr for 2 hours, and 103 target cells/well were mixed with CTLs at the effector-target (E/T) ratio indicated in a standard 4-hour cytotoxicity. All assays were performed at least in duplicate. Some target cells were pretreated with interferon γ (IFN-γ; 500 U/mL) and TNF-α (10 ng/mL; both from R&D Systems) for 48 hours as indicated. Percent specific lysis was calculated as follows: ([experimental cpm − spontaneous cpm]/[maximum cpm − spontaneous cpm]) × 100, where cpm indicates counts per minute.

cDNA library construction

The cDNA library used in the present study was the same one that had been used to identify HLA-A31- and HLA-A33-restricted cathepsin H-encoded mHAs (ACC-4 and ACC-5) previously.11 The cDNA library was constructed from mRNA of a B-LCL derived from an AML patient (UPN-027) using the SuperScript Plasmid System (Invitrogen). The library contained 1.5 × 106 cDNA clones with an average insert size of approximately 2500 bp. cDNA pools, each consisting of approximately 120 and 5 clones for initial and second screens, respectively, were expanded for 24 hours in 96 deep-well plates, and plasmid DNA was extracted with the QIAprep 96 Turbo Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Transfection of 293T cells and ELISA

Twenty thousand 293T cells retrovirally transduced with HLA-B*4403 were plated in each well of 96-well flat-bottomed plates, cultured overnight at 37°C, then transfected with 0.12 μg of plasmid containing a pool of the cDNA library using Trans IT-293 (Mirus, Madison, WI). Ten thousand CTL-2A12 cells were added to each well 20 hours after transfection. After overnight incubation at 37°C, 50 μL of supernatant was collected and IFN-γ was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Genotyping of polymorphisms

Genomic DNA was isolated from each B-LCL with a QIAamp DNA blood kit (Qiagen). Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized by standard methods. Genomic DNA or cDNA was amplified using KOD-plus-DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) temperature profile was 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 58°C for 20 seconds, and 68°C for 40 seconds on a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

The primer sequences used to amplify from exon 1 to exon 4 of HMSD cDNA were as follows: sense, 5′-CCTCTCCGACCCGGTCTC-3′; antisense, 5′-GGGAAAAGCTAAAGCTAGAGAAAA-3′. Exonic sequence and intronic sequence adjacent to HMSD exon 1 and 2 were amplified with primers as follows: exon 1 sense, 5′-GACTGAAAACTCCCGGACAG-3′; exon 1 antisense, 5′-GAAAGGTCTGGAGCAACAGG-3′; exon 2 sense, 5′-GCAGACATTCACTCACAGCA-3′; exon 2 antisense, 5′-AAGCACCCACATGAGTGACC-3′. PCR products were purified and directly sequenced with the same primer.

Construction of minigenes and truncated genes for HMSD-v

Mammalian expression plasmids containing the full-length or truncated forms of the HMSD-v cDNA were constructed by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR using the isolated cDNA clone as a template. The constructs all encoded a Kozak sequence and initiator methionine (CCACC-ATG) and a stop codon (TAA). All products were ligated into HindIII-NotI-cut pEAK10 vector (Edge Bio Systems, Gaithersburg, MD) and verified by sequencing.

Epitope reconstitution assay

The candidate HMSD-encoded epitopes were synthesized by standard Fmoc chemistry. 51Cr-labeled donor B-LCLs were incubated for 30 minutes in complete medium containing 10-fold serial dilutions of the peptides and then used as targets in standard cytotoxicity assays.

Real-time PCR assay for HMSD and HMSD-v expression

cDNAs were prepared from various hematologic malignant cell lines, primary cell cultures, freshly isolated CD34+ bone marrow (BM) and peripheral-blood hematopoietic cells and their subpopulations, immature and mature DCs, activated B and T cells, CD34+ subsets of primary leukemic cells, and CD138+ subsets of primary MM cells. Cell sorting was performed using magnetic-activated cell separation (MACS) immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergish Gladbach, Germany). A panel of cDNA made from different human adult and fetal tissues was purchased (MTC panels human I and II; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using the TaqMan assay as described previously.11 Because of uncertainty of which allele(s) were included in each cDNA pool from the MTC panels, quantitative PCR primers and a probe were designed to detect the exon 3-4 boundary, which is shared by both alleles. The following sequences spanning the exon 3-4 boundary were used as primers with TaqMan probe to detect both HMSD and HMSD-v transcripts simultaneously: sense, 5′-AGAACTGCCAACGGGCTCTT-3′; antisense, 5′-TTGGTAGAATTTGCCACAGGAAT-3′; probe, 5′-(FAM)-CTTATGATTTCCTCACAGGTT-(MGB)-3′. To selectively detect HMSD-v transcripts, the following oligonucleotides specific for the exon 1-3 boundary were used: sense, 5′-CTCCGACCCGGTCTCACTT-3′; antisense, 5′-TCTCCATCTTCACCTCCGATTT-3′; probe, 5′-(FAM)-CAAAGTGCCCCAGTTC-(MGB)-3′.

CD45 mRNA expression was detected as described previously.21 A primer and probe set for human GAPDH (Applied Biosystems) was used as an internal control. PCR was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions in the ABI PRISM 7700HT Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems). Samples were quantified using relative standard curves for each experiment. All results were normalized with respect to the internal control and are expressed relative to the levels found in recipient B-LCLs.

LSC engraftment assay of AML cells in immunodeficient NOG mice

BM cells were obtained from patients with AML at diagnosis and then positively selected for CD34+ subsets using MACS immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi). NOD/Shi-scid, IL-2Rγcnull (NOG) mice22 were purchased from the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Kanagawa, Japan). All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute. The Ethical Review Committee of the Institute approved the experimental protocol. The ACC-2D mHA-specific CTL clone 3B56 restricted by the same HLA-B*4403 allele as CTL-2A12 was used as a control CTL clone for this assay. AML cells (7.0 × 106) were preincubated for 16 hours in CTL medium supplemented with 25 units/mL recombinant human IL-2 at 37°C with 5% CO2 either alone or in the presence of CTL-2A12 or CTL-3B5 at a T-cell/AML cell ratio of 5:1. Thereafter, the cultures were harvested and resuspended in a total volume of 300 μL and were inoculated via the tail vein of 8- to 12-week-old NOG mice (3 mice per group). Five weeks after inoculation, mice were killed, peripheral blood was aspirated from the heart, and BM cells were obtained by flushing the femora with complete medium. Nucleated cells were prepared for flow cytometry by incubation at 4°C for 20 minutes in PBS and 2% FCS with antihuman CD45 and CD34 (all from BD Biosciences) and were analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest 3.3 software (BD Biosciences). Percentage of engraftment was examined by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test.

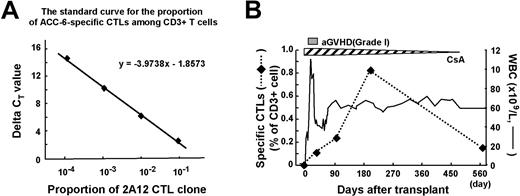

Real-time PCR assay for detecting CTLs specific for ACC-6, a newly identified mHA

Complementary DNAs for a standard curve were prepared from mixtures of ACC-6–specific CTL clone (CTL-2A12) at various ratios with CD3+ cells from healthy donors, and cDNAs of peripheral blood CD3+ cells from the donor and patient before and after HCT were prepared from the AML patient (UPN-027). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using a TaqMan assay as described in “Real-time PCR assay for HMSD and HMSD-v expression.” The primers and fluorogenic probe sequences spanning the CTL-2A12 complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) were used to detect T cells carrying the CDR3 sequences identical to that of CTL-2A12. Samples were quantified with the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method. The delta CT value was determined by subtracting the average GAPDH CT value from the average CTL-2A12 CDR3 CT value. The standard curve for the proportion of CTL-2A12 among CD3+ cells (Figure 7A) was composed by plotting mean delta CT values for each ratio, and the percentages of T cells carrying the CDR3 sequence identical to CTL-2A12A were calculated by using this standard curve.

Results

Characterization of a CTL clone

The CD8+ CTL clone 2A12 (CTL-2A12) was 1 of 24 putative CTL clones isolated from day-197 post-HCT PBMCs of a male with refractory AML with multilineage dysplasia (UPN-027) receiving an HLA-identical HCT from his brother (A*2402, A*3303, B75, B*4403, Cw3, DR4, DR6).11 The patient developed grade 1 acute GVHD in the first 2 years after transplantation and then suffered from glomerular IgG deposition and mild bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. He is alive and in good condition and has been disease free for more than 3 years.

Cytotoxicity assays revealed that CTL-2A12 lysed the recipient B-LCL and less efficiently phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated T-cell blasts but not donor B-LCL or natural killer (NK)-sensitive K562 cells (Figure 1A,B). No cytotoxicity was observed against the recipient's dermal fibroblasts and BM-derived fibroblasts even after treatment with IFN-γ and TNF-α (Figure 1B). Cytotoxicity against recipient B-LCL was blocked by anti-HLA class I antibody (Ab) but not by anti-HLA-DR Ab, suggesting HLA class I-restricted recognition of mHA (data not shown). Based on the screening results of a panel of B-LCLs derived from individuals partially sharing HLA class I alleles with the recipient (Figure 1C UR1 and UR2; data not shown), those from HLA-mismatched individuals that were transduced with either HLA-A*3303 or -B*4403 were further tested. CTL-2A12 lysed UR3 B-LCLs when transduced with HLA-B*4403. In addition, UR3 B-LCLs transduced with HLA-B*4402 were also recognized, indicating that the mHA peptide can be presented by both HLA-B*4403 and -B*4402 (Figure 1C).

Specificity of the HLA-B44–restricted CTL clone 2A12. The cytolytic activity of CTL-2A12 was evaluated in a standard 4-hour 51Cr release assay at the indicated E/T ratios. (A) CTL-2A12 recognition of target cells derived from recipient (Rt) but not donor (Do) B-LCLs. NK-sensitive K562 cells were used to determine nonspecific lysis. (B) CTL-2A12 recognition of Rt PHA-stimulated T cells (PHA blasts) but not of Rt dermal fibroblasts and bone marrow (BM)-derived fibroblasts pretreated with 500 U/mL IFN-γ and 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 48 hours before 51Cr labeling. (C) CTL-2A12 recognition of an HLA-B*4403- and -B*4402-restricted mHA epitope. The following target cells were tested: Rt B-LCL, B-LCLs of 2 unrelated individuals (UR1 and UR2) sharing an HLA-A33, B44 haplotype with the recipient, and B-LCLs of an HLA class I-mismatched individual (UR3) that were transduced with either HLA-A*3303, B*4403, or B*4402 (E/T ratio, 30:1).

Specificity of the HLA-B44–restricted CTL clone 2A12. The cytolytic activity of CTL-2A12 was evaluated in a standard 4-hour 51Cr release assay at the indicated E/T ratios. (A) CTL-2A12 recognition of target cells derived from recipient (Rt) but not donor (Do) B-LCLs. NK-sensitive K562 cells were used to determine nonspecific lysis. (B) CTL-2A12 recognition of Rt PHA-stimulated T cells (PHA blasts) but not of Rt dermal fibroblasts and bone marrow (BM)-derived fibroblasts pretreated with 500 U/mL IFN-γ and 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 48 hours before 51Cr labeling. (C) CTL-2A12 recognition of an HLA-B*4403- and -B*4402-restricted mHA epitope. The following target cells were tested: Rt B-LCL, B-LCLs of 2 unrelated individuals (UR1 and UR2) sharing an HLA-A33, B44 haplotype with the recipient, and B-LCLs of an HLA class I-mismatched individual (UR3) that were transduced with either HLA-A*3303, B*4403, or B*4402 (E/T ratio, 30:1).

Identification of the gene encoding the mHA and elucidation of the mechanism of antigenicity

cDNA expression cloning using a cDNA library was conducted as described in “Patients, materials, and methods, cDNA library construction.” In the first round of screening, 1 of 96 plasmid pools induced IFN-γ production by CTL-2A12. Two-step subclonings (∼5 cDNAs and 1 cDNA) of this pool finally resulted in the isolation of a cDNA clone (data not shown).

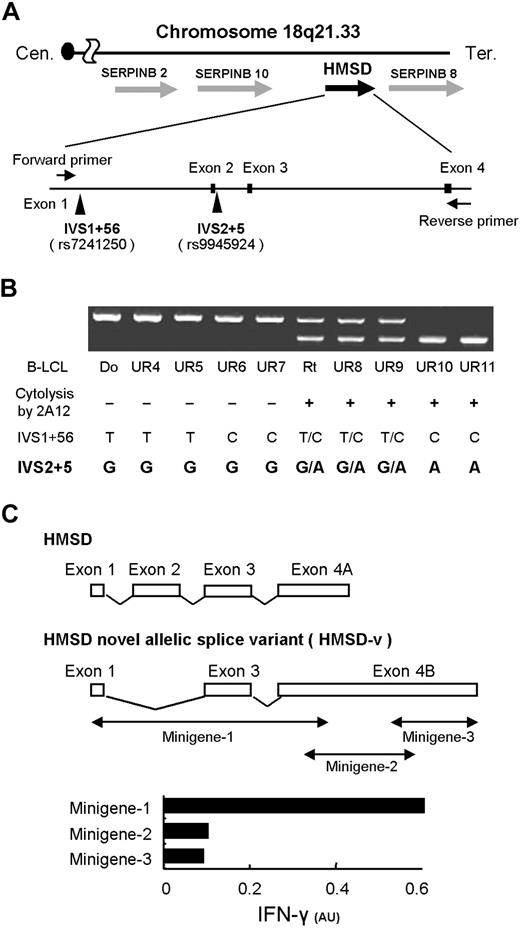

The cDNA clone was sequenced and a BLAST search23 revealed that this cDNA clone was previously unreported, but partially identical to XM_209104. XM_209104 was designated histocompatibility (minor) serpin domain containing (HMSD) by the Human Genome organization Nomenclature Committee (Figure 2A). HMSD is a gene predicted by RefSeq24 based on previously reported expressed sequence tags (ESTs). We speculated that this novel cDNA clone was a splice variant of HMSD (Figure 2C) because it had exons 1 and 3 plus exon 4B but lacked exon 2. The first third of exon 4B was identical to exon 4A of HMSD. Primers were set in exon 1 and the 5′ part of exon 4 (Figure 2A), and RT-PCR was carried out using cDNA from B-LCLs typed by CTL-2A12. Interestingly, these PCR products from mHA− samples consisted of 1 longer band (674 bp), whereas those from mHA+ samples consisted of the longer band and a shorter band (500 bp) or a single shorter band. This association was concordant with all 34 samples we examined (Figure 2B; data not shown), which revealed that differential expression of HMSD and its splice variant is responsible for antigenicity. Exon 1, exon 2, and introns adjacent to exons 1 and 2 were sequenced to account for the alternative splicing, and we found 2 sequence polymorphisms of intronic SNPs, the intervening sequence 1+56 (IVS1+56; rs7241250) and IVS2+5 (rs9945924), in our samples. The correlation between these 2 SNPs and susceptibility to CTL-2A12 was studied, which demonstrated that IVS2+5G>A, but not the SNP at IVS1+56, was completely concordant with cytolysis by CTL-2A12 (Figure 2B). Because the alternatively spliced cDNA clone isolated was generated as an allelic splice variant due to SNP, it was designated HMSD-v.

Identification of a novel splice variant transcript of HMSD encoding the mHA. (A) Summary of genome mapping around chromosome 18q21.33 showing relative positions of HMSD. Two identical cDNA clones were homologous to exons 1 and 3 plus exon 4 but lacked exon 2. This novel allelic splice variant of HMSD was designated HMSD-v (panel C). Search for potential SNPs responsible for the alternative splicing revealed 2 potential SNPs at IVS1+56 and IVS2+5 (arrowheads). Cen indicates centromere, Tel, telomere. (B) The correlation between sequence polymorphisms of the 2 SNPs and susceptibility of B-LCLs to CTL-2A12. Detection of allelic polymorphisms in B-LCLs was conducted by RT-PCR. Primers were set in exon 1 and the 5′ part of exon 4 of HMSD (horizontal arrows in panel A). Due to the lack of exon 2, the mHA+ allele produced a smaller PCR product. Genotyping of the 2 SNPs mentioned above and cytolysis of B-LCLs by CTL-2A12 are summarized below the results of electrophoresis. The correlation between the genotyping results of SNPs at IVS2+5, CTL-2A12 cytolysis, and the bands of electrophoresis produced by mHA+ and mHA− allele showed complete concordance. (C) Schematic representation of HMSD and HMSD-v and mapping of the region encoding the CTL-2A12 mHA epitope by minigenes. The HMSD-v cDNA was divided into 3 minigenes, and mammalian expression plasmids containing individual minigenes were constructed. 293T/B*4403 cells were transfected with individual plasmids and cocultured with CTL-2A12. Supernatants were then harvested and assayed for IFN-γ production by ELISA. Release of IFN-γ is expressed in arbitrary units (AUs) corresponding to optical density at 630 nm.

Identification of a novel splice variant transcript of HMSD encoding the mHA. (A) Summary of genome mapping around chromosome 18q21.33 showing relative positions of HMSD. Two identical cDNA clones were homologous to exons 1 and 3 plus exon 4 but lacked exon 2. This novel allelic splice variant of HMSD was designated HMSD-v (panel C). Search for potential SNPs responsible for the alternative splicing revealed 2 potential SNPs at IVS1+56 and IVS2+5 (arrowheads). Cen indicates centromere, Tel, telomere. (B) The correlation between sequence polymorphisms of the 2 SNPs and susceptibility of B-LCLs to CTL-2A12. Detection of allelic polymorphisms in B-LCLs was conducted by RT-PCR. Primers were set in exon 1 and the 5′ part of exon 4 of HMSD (horizontal arrows in panel A). Due to the lack of exon 2, the mHA+ allele produced a smaller PCR product. Genotyping of the 2 SNPs mentioned above and cytolysis of B-LCLs by CTL-2A12 are summarized below the results of electrophoresis. The correlation between the genotyping results of SNPs at IVS2+5, CTL-2A12 cytolysis, and the bands of electrophoresis produced by mHA+ and mHA− allele showed complete concordance. (C) Schematic representation of HMSD and HMSD-v and mapping of the region encoding the CTL-2A12 mHA epitope by minigenes. The HMSD-v cDNA was divided into 3 minigenes, and mammalian expression plasmids containing individual minigenes were constructed. 293T/B*4403 cells were transfected with individual plasmids and cocultured with CTL-2A12. Supernatants were then harvested and assayed for IFN-γ production by ELISA. Release of IFN-γ is expressed in arbitrary units (AUs) corresponding to optical density at 630 nm.

Identification of an HLA-B*4403-restricted epitope of HMSD-v and epitope reconstitution assay

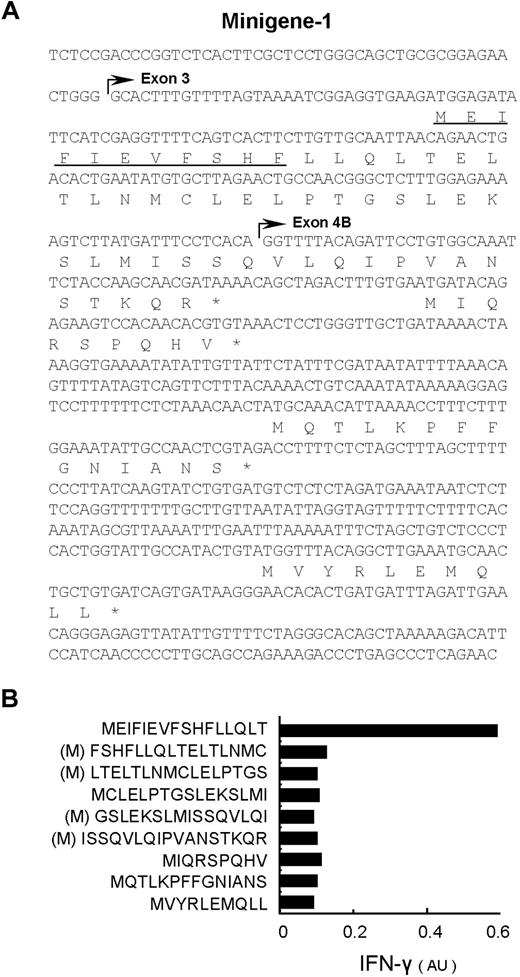

To identify the epitope recognized by CTL-2A12, HMSD-v cDNA was divided into 3 minigenes overlapping each other by around 100 bp (Figure 2C) and then transfected into 293T/B*4403 cells. CTL-2A12 recognized 293T/B*4403 transfected with minigene-1, which expressed the first 809 bp of HMSD-v (Figure 2C). After searching all frames, 2 reading frames in the HMSD-v transcript were found to be able to encode polypeptides starting with an ATG codon, which was at least 9 amino acids (aa's) long (Figure 3A). The longest 53-mer polypeptide was divided into 16- or 17-aa peptides with 9 aa's overlapping each other, and downstream 3 peptides were expressed as minigenes starting with ATG (methionine) in 293T/B*4403 cells and tested. The construct encoding the first polypeptide, MEIFIEVFSHFLLQLT, was clearly recognized by CTL-2A12 (Figure 3B). To determine the mHA epitope, the minigene was serially deleted from its C-terminus and tested. An undecameric peptide was sufficient to induce IFN-γ production from CTL-2A12 (Figure 3A underlined; Table 1).

The nucleotide and deduced amino-acid sequences of minigene-1 encoding the CTL-2A12 mHA epitope. (A) Exon 2 encoding the original start codon in HMSD was deleted. After searching all frames, 2 reading frames in the HMSD-v transcript shown here were found to be able to encode polypeptides longer than 9 aa's starting with an ATG codon. Polypeptides longer than 9 aa's are all indicated. Asterisks indicate a stop codon. The start of exon 3 and exon 4B are indicated with horizontal arrows. The epitope recognized by CTL-2A12 is underlined (see Figure 4). (B) Six small minigenes with 9 aa's overlapping derived from the longest 53-mer polypeptide and downstream 3 minigenes (shown in panel A) were expressed in 293T/B*4403 cells and cocultured with CTL-2A12. Production of IFN-γ was similarly measured by ELISA. Release of IFN-γ is expressed in arbitrary units (AUs) corresponding to optical density at 630 nm. (M) indicates an artificially added methionine as a start codon.

The nucleotide and deduced amino-acid sequences of minigene-1 encoding the CTL-2A12 mHA epitope. (A) Exon 2 encoding the original start codon in HMSD was deleted. After searching all frames, 2 reading frames in the HMSD-v transcript shown here were found to be able to encode polypeptides longer than 9 aa's starting with an ATG codon. Polypeptides longer than 9 aa's are all indicated. Asterisks indicate a stop codon. The start of exon 3 and exon 4B are indicated with horizontal arrows. The epitope recognized by CTL-2A12 is underlined (see Figure 4). (B) Six small minigenes with 9 aa's overlapping derived from the longest 53-mer polypeptide and downstream 3 minigenes (shown in panel A) were expressed in 293T/B*4403 cells and cocultured with CTL-2A12. Production of IFN-γ was similarly measured by ELISA. Release of IFN-γ is expressed in arbitrary units (AUs) corresponding to optical density at 630 nm. (M) indicates an artificially added methionine as a start codon.

Fine epitope mapping with minigenes

| Minigene sequence . | Length, bp . | CTL response . | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | L | Q | L | T | 16 | + |

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | L | Q | L | 15 | + | |

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | L | Q | 14 | + | ||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | L | 13 | + | |||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | 12 | + | ||||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | 11 | + | |||||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | 10 | − | ||||||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | 9 | − | |||||||

| Minigene sequence . | Length, bp . | CTL response . | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | L | Q | L | T | 16 | + |

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | L | Q | L | 15 | + | |

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | L | Q | 14 | + | ||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | L | 13 | + | |||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | L | 12 | + | ||||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | F | 11 | + | |||||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | H | 10 | − | ||||||

| M | E | I | F | I | E | V | F | S | 9 | − | |||||||

To determine the mHA epitope, a minigene encoding 16 amino acids, which stimulated CTL-2A12, was serially deleted from its C terminus and then tested by ELISA. An undecameric but not decameric peptide was sufficient to induce IFN-γ production from the CTL-2A12.

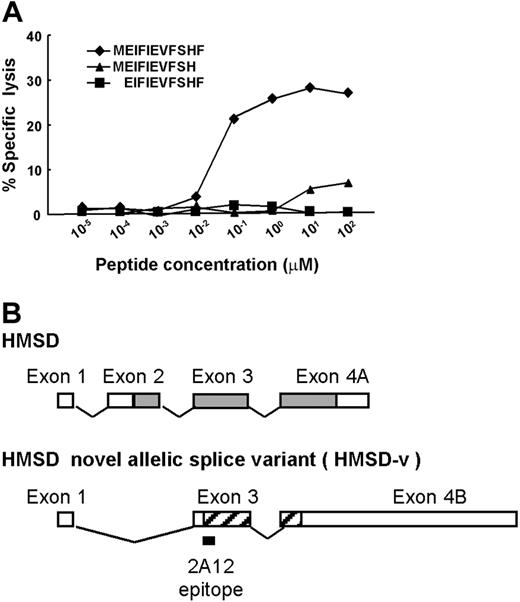

Subsequently, a peptide reconstitution assay was conducted. Undecameric peptide (MEIFIEVFSHF), its C-terminal deleted decameric peptide (MEIFIEVFSH), and N-terminal deleted decameric peptide (EIFIEVFSHF) were synthesized and titrated by adding to the mHA− donor B-LCL, and among these, only undecameric peptide showed dose-dependent cytolysis with a half-maximal lysis at 20 nM (Figure 4A). This undecameric peptide contains the HLA-B*4403 anchor motif—a glutamic acid at position 2 and a phenylalanine at the C-terminus25,26 —although undecameric peptide is not common as a T-cell epitope. We designated the mHA as ACC-6 (Aichi Cancer Center No. 6).

Identification of the CTL-2A12 minimal mHA epitope. (A) A peptide reconstitution assay was conducted to determine the concentration of peptides needed to stimulate CTL-2A12. Undecameric peptide (MEIFIEVFSHF), its C-terminal deleted decameric peptide (MEIFIEVFSH), and N-terminal deleted decameric peptide (EIFIEVFSHF) were synthesized and titrated by adding to the antigen-negative donor B-LCL. (B) Transcript of HMSD (encoding a 139-mer polypeptide) predicted by computer algorithm is indicated with ▩. ▨ indicates the presumed HMSD-v transcript region encoding a 53-mer polypeptide starting with an ATG codon and including the CTL-2A12 epitope. The location of the identified 2A12 epitope is shown below the HMSD-v cDNA. These 2 polypeptides have no homology because they are translated from different reading frames.

Identification of the CTL-2A12 minimal mHA epitope. (A) A peptide reconstitution assay was conducted to determine the concentration of peptides needed to stimulate CTL-2A12. Undecameric peptide (MEIFIEVFSHF), its C-terminal deleted decameric peptide (MEIFIEVFSH), and N-terminal deleted decameric peptide (EIFIEVFSHF) were synthesized and titrated by adding to the antigen-negative donor B-LCL. (B) Transcript of HMSD (encoding a 139-mer polypeptide) predicted by computer algorithm is indicated with ▩. ▨ indicates the presumed HMSD-v transcript region encoding a 53-mer polypeptide starting with an ATG codon and including the CTL-2A12 epitope. The location of the identified 2A12 epitope is shown below the HMSD-v cDNA. These 2 polypeptides have no homology because they are translated from different reading frames.

HMSD and HMSD-v mRNA expression in various hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells

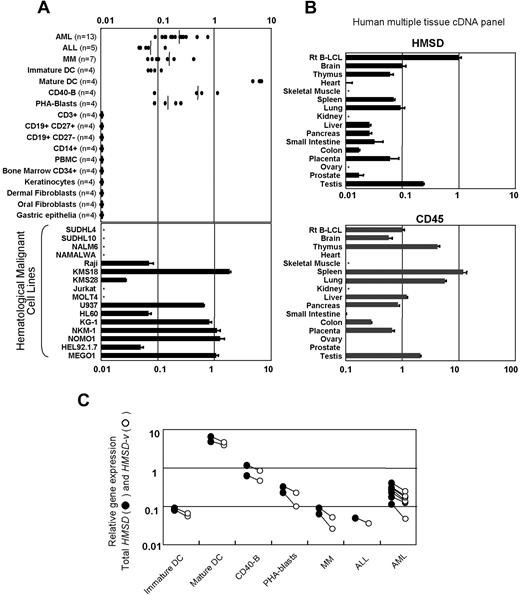

To determine the expression of HMSD and HMSD-v mRNA in a more comprehensive manner, real-time PCR was performed. Individual real-time PCR analysis specific for the HMSD-v transcript and for both HMSD and HMSD-v transcripts revealed that both were equally present in cDNA samples from B-LCLs heterozygous for the defined mHA (data not shown). Thus, further real-time PCR analysis was performed to quantify the total expression of both transcripts partly because mHA allelic status of commercial tissue cDNAs was unknown. High levels of expression were observed in primary AML and MM cells, mature DCs, CD40-B cells and PHA blasts (Figure 5A top panel), and malignant hematopoietic cell lines (especially those of myeloid lineage; Figure 5A bottom panel). In contrast, most normal tissues (Figure 5B top panel), including resting primary hematopoietic cells (Figure 5A top panel), showed lower or no expression, except for testis, which expressed a moderate amount of transcript. Weak expression observed in commercial cDNA from nonhematopoietic tissues including brain, lung, and placenta could be caused at least in part by contaminating hematopoietic cells or resident cells of hematopoietic origin such as pulmonary macrophages, because relatively high levels of CD45 transcript were detected in those tissues (Figure 5B bottom panel).

Selective mRNA expression of HMSD and HMSD-v. (A) Total HMSD expression was determined by real-time quantitative PCR in various normal tissues and malignant hematopoietic cell lines using a primer-probe set that detects the exon 3-4 boundary. Targeted mRNA expression in the recipient B-LCL is set as 1.0. In the top dotted plot graph, cDNAs prepared from CD34+ subsets of primary leukemic cells and CD138+ subsets of primary MM cells, freshly isolated hematopoietic cells, their subpopulations, immature and mature DCs, activated B and T cells, freshly isolated CD34+ bone marrow cells, and primary cell cultures were similarly analyzed. Values in the parentheses indicate the number of the individuals tested. In the bottom and middle panels, cDNAs prepared from 16 hematologic malignant cell lines are shown. SUDHL4 and SUDHL10 are derived from B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NALM6 from acute B-lymphocyte leukemia; NAMALWA and Raji from Burkitt lymphoma; KMS18 and KMS28 from multiple myeloma (MM); Jurkat and MOLT4 from acute T-lymphocyte leukemia; U937 from histiocytic lymphoma; HL60, KG-1, NKM-1, NOMO1, and HEL92.1.7 from acute myeloid leukemia; and MEGO1 from chronic myeloid leukemia (blast crisis). (B) cDNAs of 15 normal tissue samples purchased from Clontech (MTC panels human I and II) were analyzed for total HMSD expression (top panel) and CD45 mRNA expression (bottom panel). Messenger RNA expression in the recipient B-LCL is set as 1.0. (C) HMSD-v expression levels (○) were compared with total HMSD expression levels (●) using a primer-probe set that detects the exon 1-3 boundary specific for HMSD-v mRNA. Among primary hematopoietic cells shown in the top of panel A, cells that were found to be heterozygous for ACC-6 allele were further selected and tested. Paired samples are linked.

Selective mRNA expression of HMSD and HMSD-v. (A) Total HMSD expression was determined by real-time quantitative PCR in various normal tissues and malignant hematopoietic cell lines using a primer-probe set that detects the exon 3-4 boundary. Targeted mRNA expression in the recipient B-LCL is set as 1.0. In the top dotted plot graph, cDNAs prepared from CD34+ subsets of primary leukemic cells and CD138+ subsets of primary MM cells, freshly isolated hematopoietic cells, their subpopulations, immature and mature DCs, activated B and T cells, freshly isolated CD34+ bone marrow cells, and primary cell cultures were similarly analyzed. Values in the parentheses indicate the number of the individuals tested. In the bottom and middle panels, cDNAs prepared from 16 hematologic malignant cell lines are shown. SUDHL4 and SUDHL10 are derived from B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NALM6 from acute B-lymphocyte leukemia; NAMALWA and Raji from Burkitt lymphoma; KMS18 and KMS28 from multiple myeloma (MM); Jurkat and MOLT4 from acute T-lymphocyte leukemia; U937 from histiocytic lymphoma; HL60, KG-1, NKM-1, NOMO1, and HEL92.1.7 from acute myeloid leukemia; and MEGO1 from chronic myeloid leukemia (blast crisis). (B) cDNAs of 15 normal tissue samples purchased from Clontech (MTC panels human I and II) were analyzed for total HMSD expression (top panel) and CD45 mRNA expression (bottom panel). Messenger RNA expression in the recipient B-LCL is set as 1.0. (C) HMSD-v expression levels (○) were compared with total HMSD expression levels (●) using a primer-probe set that detects the exon 1-3 boundary specific for HMSD-v mRNA. Among primary hematopoietic cells shown in the top of panel A, cells that were found to be heterozygous for ACC-6 allele were further selected and tested. Paired samples are linked.

It is possible that HMSD-v is differentially expressed from HMSD in cell types other than B-LCLs, where both transcripts were generated at similar levels. Thus, we examined both total HMSD and HMSD-v transcripts in various primary cells that were heterozygous for the ACC-6 allele. As shown in Figure 5C, the HMSD-v levels were approximately half of total HMSD levels in all cell types tested.

Inhibition of human AML-cell engraftment in severely immunodeficient NOG mice by CTL-2A12

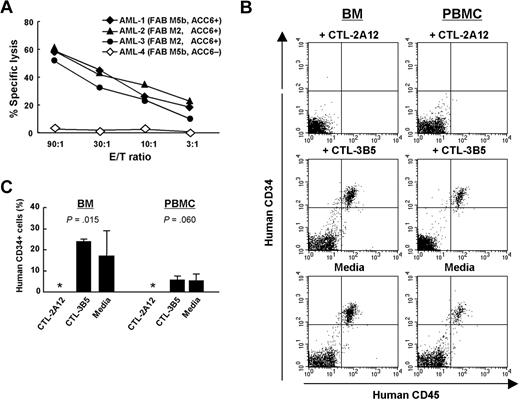

We first confirmed that the positively selected CD34+ fraction of primary AML cells positive for HLA-B*4403 and the ACC-6+ allele (all heterozygous) by genotyping was efficiently lysed by CTL-2A12 (Figure 6A). The mRNA expression level of total HMSD in these AML cells was 47% (AML-1), 28% (AML-2), and 24% (AML-3) of that in the ACC-6-heterozygous recipient B-LCL, respectively.

Inhibition of human AML stem cell engraftment in severely immunodeficient NOG mice by CTL-2A12. (A) Specific lysis by CTL-2A12 of primary leukemia cells. A standard 4-hour 51Cr release assay was conducted at the indicated E/T ratios. The CD34+ fraction of 3 primary AML cells positive for HLA-B*4403 and the ACC-6+ allele by genotyping (AML-1, -2 and -3; the expression level of HMSD was 47%, 28%, and 24% of that in the recipient B-LCL, respectively) and 1 HLA-B*4403+, ACC-6 allele-negative (AML-4) were tested. FAB denotes French-American-British classification. (B) Representative flow cytometric profiles of peripheral blood and BM cells from AML-inoculated NOG mice for the expression of human CD45 and CD34. Peripheral blood and BM cells were obtained 5 weeks after inoculation from mice receiving 7.0 × 106 AML-2 CD34+ cells (negative for ACC-2D mHA) that had been incubated with either CTL-2A12 (top), control CTL-3B5 (middle; HLA-B*4403-restricted, ACC-2D mHA-specific CTL), or culture medium alone (bottom) at a T-cell/AML cell ratio of 5:1. (C) Summary of results from engraftment experiments. Mean (± SD) percentage of CD45 and CD34 double-positive cells of 3 mice in each group at 5 weeks after inoculation and the P values examined by 1-way ANOVA test are shown. Asterisk indicates that CD45 and CD34 double-positive cells were not detectable in NOG mice inoculated with AML-2 cells preincubated with CTL-2A12.

Inhibition of human AML stem cell engraftment in severely immunodeficient NOG mice by CTL-2A12. (A) Specific lysis by CTL-2A12 of primary leukemia cells. A standard 4-hour 51Cr release assay was conducted at the indicated E/T ratios. The CD34+ fraction of 3 primary AML cells positive for HLA-B*4403 and the ACC-6+ allele by genotyping (AML-1, -2 and -3; the expression level of HMSD was 47%, 28%, and 24% of that in the recipient B-LCL, respectively) and 1 HLA-B*4403+, ACC-6 allele-negative (AML-4) were tested. FAB denotes French-American-British classification. (B) Representative flow cytometric profiles of peripheral blood and BM cells from AML-inoculated NOG mice for the expression of human CD45 and CD34. Peripheral blood and BM cells were obtained 5 weeks after inoculation from mice receiving 7.0 × 106 AML-2 CD34+ cells (negative for ACC-2D mHA) that had been incubated with either CTL-2A12 (top), control CTL-3B5 (middle; HLA-B*4403-restricted, ACC-2D mHA-specific CTL), or culture medium alone (bottom) at a T-cell/AML cell ratio of 5:1. (C) Summary of results from engraftment experiments. Mean (± SD) percentage of CD45 and CD34 double-positive cells of 3 mice in each group at 5 weeks after inoculation and the P values examined by 1-way ANOVA test are shown. Asterisk indicates that CD45 and CD34 double-positive cells were not detectable in NOG mice inoculated with AML-2 cells preincubated with CTL-2A12.

Next, to determine whether the ACC-6 mHA recognized by CTL-2A12 is indeed expressed on LSCs and thus might have been involved in a GVL effect in AML patient UPN-027, we performed the LSC engraftment assay as previously reported27 but substituted the significantly immunodeficient NOG mice because the absence of NK activity in NOG mice has been shown to facilitate the engraftment level of xenogenic human hematopoietic cells.22 The CD34+ fractions of primary AML cells that were lysed by CTL-2A12 (AML-2 in Figure 6A) were selected for this assay, since it was found to be negative for the HLA-B*4403-restricted mHA ACC-2D,6 and not lysed by the ACC-2D-specific clone CTL-3B5 (data not shown), which was used as an irrelevant control. These AML CD34+ cells were incubated in vitro for 16 hours either alone or in the presence of CTL-2A12 or control CTL-3B5 at a T-cell/AML cell ratio of 5:1. Subsequently the mixtures were inoculated into NOG mice. After 5 weeks, flow cytometric analysis of BM and PBMCs was conducted to study the expression of human CD45, CD34, and CD8. Representative flow cytometric profiles are shown in Figure 6B. BM cells of control mice receiving AML-2 cells cultured in medium alone or with control CTL-3B5 before inoculation were found to contain 2.79% to 25.44% (mean, 20.29%) human CD45+ CD34+ cells, whereas PBMCs of the same 2 groups of mice contained 2.97% to 9.69% human cells. In contrast, human cells were not detectable in either BM or PBMCs of the mice inoculated with AML cells precultured with CTL-2A12. Percentage AML engraftment at 5 weeks after inoculation under these conditions is summarized in Figure 6C, indicating that CTL-2A12 eradicated AML stem cells with repopulating capacity (P = .015 for BM).

Follow-up of ACC-6–specific CTLs in peripheral blood from an AML patient (UPN-027)

To detect ACC-6–specific CTLs in peripheral blood from AML patient UPN-027 and from his donor, we performed real-time quantitative PCR (Figure 7A) using a set of primers and a fluorogenic probe specific for the unique CDR3 sequence of the CTL-2A12 TCR β chain at several time points. Although ACC-6-specific CTLs were not detected in blood samples from the donor and the patient before HCT, they became detectable in patient samples after HCT at frequencies of 0.11%, 0.23%, 0.83%, and 0.16% among CD3+ cells at days 29, 91, 197, and 548, respectively (Figure 7B). During this period of time, there were no documented clinical manifestations of recurrent disease, and only grade 1 acute GVHD was noted.

Detection of ACC-6–specific CTLs in peripheral blood from the AML patient (UPN-027) by real-time quantitative PCR using a set of primers and fluorogenic probe specific for the CTL-2A12 CDR3 sequence. (A) The standard curve for the proportion of ACC-6–specific CTL-2A12 serially diluted into CD3+ cells from healthy donors using the comparative CT (threshold cycle) method. The y-axis is delta CT value. The x-axis is the log proportion of ACC-6–specific CTLs among CD3+ T cells. (B) The frequency of T cells carrying the CDR3 sequence of CTL-2A12 over a period of 1.5 years after HCT. The percentages of such T cells among CD3+ T cells (left y-axis) were estimated by using a standard curve in panel A and are indicated before HCT and after HCT at day 29, day 91, day 197, and day 548, respectively (diamonds with dotted line). Also noted are white blood cell (WBC) counts (right y-axis), acute GVHD (gray bar), and immunosuppressive therapy with cyclosporine A (CsA; hatched bar) during the same time period.

Detection of ACC-6–specific CTLs in peripheral blood from the AML patient (UPN-027) by real-time quantitative PCR using a set of primers and fluorogenic probe specific for the CTL-2A12 CDR3 sequence. (A) The standard curve for the proportion of ACC-6–specific CTL-2A12 serially diluted into CD3+ cells from healthy donors using the comparative CT (threshold cycle) method. The y-axis is delta CT value. The x-axis is the log proportion of ACC-6–specific CTLs among CD3+ T cells. (B) The frequency of T cells carrying the CDR3 sequence of CTL-2A12 over a period of 1.5 years after HCT. The percentages of such T cells among CD3+ T cells (left y-axis) were estimated by using a standard curve in panel A and are indicated before HCT and after HCT at day 29, day 91, day 197, and day 548, respectively (diamonds with dotted line). Also noted are white blood cell (WBC) counts (right y-axis), acute GVHD (gray bar), and immunosuppressive therapy with cyclosporine A (CsA; hatched bar) during the same time period.

Discussion

Antigenicity of the majority of previously identified human mHAs is generated by differences in amino-acid sequence between donor and recipient due to nonsynonymous SNPs. In this study, we identified a novel HLA-B44–restricted mHA epitope (ACC-6) encoded by an allelic splice variant of HMSD (HMSD-v) in which exclusion of exon 2 due to alternative splicing was completely controlled by an intronic SNP at IVS2+5. Indeed, by RT-PCR, the novel HMSD-v was not detected in cDNA samples from mHA− B-LCLs, whereas it was detectable in mHA+ B-LCLs. An interesting question is why the splicing of exon 2 was completely controlled by the intronic SNP. In general, during intron splicing reactions, U1snRNA first binds the 5′ splice site of an intron, spliceosome assembly starts, lariat formation is made with several other factors, and thereafter the intron is spliced out (reviewed in Valadkhan28 ). Here U1snRNA is an important initiator of the cascade. It has been shown that aberrant splicing can result from mutations that either destroy or create splice-site consensus sequences at the 5′ splice site such that approximately half of the observed aberrant splicing is exon skipping while intron retention is rarely observed.29 In this case, we speculate that the G-to-A substitution of the intronic SNP at nucleotide 5 in intron 2 (IVS2+5G>A, 5′-GUACAU-3′), in addition to the presence of nonconsensus IVS2+4C (underlined), which is commonly observed in both mHA+ and mHA− alleles and thus is likely to be permissive, completely disrupts the consensus alignment sequence critical for U1snRNA binding (5′-GUAAGU-3′) such that U1snRNA cannot stably bind the 5′ end of intron 2 in the precursor mRNA from the mHA+ allele. A similar mutation (IVS3+5G>C, 5′-GUAACU-3′) and resultant exon 3 skipping was reported as a disease-causing mutation in the NF1 gene.30 Accordingly, intron 2 cannot be spliced out; a large lariat consisting of intron 1, exon 2, and intron 2 is formed; and then the large lariat is spliced out. In the latter case, 1 nucleotide (IVS1+4) does not match the U1snRNA sequence, but this mismatch is again likely to be permissive. Indeed, it has been shown that a mismatch at nucleotide 3, 4, or 6 of the 5′ splice site is not critical compared with others.31,32 To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of an mHA whose antigenicity is controlled by alternative splicing due to an intronic SNP, which may represent an important mechanism for the generation of mHAs.

The novel epitope was located on exon 3 and was transcribed from a reading frame different from the HMSD transcripts (Figure 4B). Although exon 3 is shared by HMSD and HMSD-v, it is speculated that polypeptide including the epitope was not being translated from HMSD, because donor B-LCL was not lysed by CTL-2A12. In general, ribosomes initiate translation from the first AUG start codon, but sometimes second or other AUG codons downstream can serve as start codons due to “leaky scanning.”33 However, it seems this is not the case for HMSD because the donor B-LCL homozygous for this allele was not lysed at all. This identification of an mHA unexpectedly generated from a previously unknown alternative transcript due to SNP has important implications for the identification of other new mHAs.

LSCs, which are present at very low frequencies, have a particularly strong capacity for proliferation, differentiation, and self-renewal34 and likely play an important role in disease refractoriness or relapse after chemotherapy and transplantation. Thus, complete eradication of such stem cells is critical for cure in any treatment modalities. The LSC engraftment assay of AML cells in immunodeficient mice has been shown to be a powerful method for testing the effect of treatment, here mHA-specific CTLs, on LSCs. In addition, preliminary analysis has shown that CTL-2A12 lysed the CD34+CD38− fraction of AML cells (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figures link at the top of the online article), which is considered to contain leukemic stem-like cells.35 These data clearly demonstrate that ACC-6 mHA is expressed on such stem cells and may serve as target for cognate CTL-2A12 in vivo.

We performed quantitative RT-PCR analyses for HMSD transcripts in various tissues with great interest because cytotoxicity assays suggested its limited expression in hematopoietic cells. Notably, HMSD showed selective expression in several hematopoietic primary tumor cells (especially those of myeloid lineage), mature DCs, and activated B and T cells. Since high expression was observed in mature DCs as in the case of HMHA1 encoding HA-1 mHA,36 immune responses to HMSD-derived mHAs may induce not only a GVL effect37 against hematopoietic tumor cells but also GVHD,38 since recipient DCs are responsible for initiating GVHD after HCT. Collectively, our data suggest that this novel mHA, ACC-6, might be a good target for immunotherapy inducing GVL if potential GVHD induction can be managed until recipient DCs have been eliminated early after HCT. Finally, relatively high expression of HMSD in the CD138+ fraction of MM cells and their susceptibility to 2A12-CTL (Figure S2) suggest that ACC-6 may serve as a potential target for immunotherapy of multiple myeloma.

It is of interest to correlate clinical outcomes with ACC-6-specific T-cell kinetics after HCT using reagents such as tetramers. The preparation of HLA-B44 tetramer, however, is known to be very difficult,39 so we used real-time quantitative RT-PCR using CTL-2A12 CDR3 sequence-specific primers/probe, because Yee et al40 have previously shown strong concordance between semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of a clone-specific CDR3 region and tetramer analysis used to monitor the fate of adoptively infused CTL clones for the treatment of melanoma. The highest frequency of 0.83% among CD3+ cells was obtained at day 197 after HCT, concordant with the fact that CTL-2A12 was generated from the PBMCs collected at that time. This magnitude is somewhat lower than that observed in the case of LRH-1-specific T cells (1.6% of CD8+ T cells) at the peak level after donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI)16 but similar to that observed in the case of HA-1-specific T cells (1000 to 6000 tetramer-positive cells per mL blood, corresponding to 0.2% to 1.0% among CD3+ cells).41 The possibility that the ACC-6 mHA might preferentially induce GVL is supported by the fact that ACC-6–specific CTLs were detectable in the recipient's peripheral blood at a relatively high level after resolution of mild acute GVHD and that LSCs could be eradicated as shown in the NOG mice model. Whether or not ACC-6 mismatching in donor-recipient pairs may be associated with an increased risk of GVHD or morbidity would need to be studied using a large cohort of patients.

The therapeutic applicability of particular mHAs, calculated from the disparity rate and restricting HLA allele frequency, is an issue of interest.42 The observed frequency of this ACC-6+ phenotype was approximately 35% (n = 48/135) in healthy Japanese donors (data not shown) and HLA-B*4403 is present in around 20% of Japanese populations, so that ACC-6 incompatibility is expected to occur in approximately 4.6% of HCT recipient-donor pairs. Because CTL-2A12 lysed HLA-B*4402+ B-LCLs possessing the ACC-6+ phenotype derived from white individuals, this novel epitope peptide can also bind to HLA-B*4402, which is a relatively common allele (around 20%) in white populations. Actually, data from the HapMap Project43 demonstrate that the genotype frequency of carrying at least one IVS2+5A (ACC-6+) allele is 0.381 for individuals registered in the Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) cell bank,44 thus this mHA should also be applicable to white patients. These results together suggest that HMSD-derived products could be attractive targets for immunotherapy and that given the possible role of intronic SNPs, a mechanism of alternative splicing should be also taken into consideration when searching for novel mHAs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr W. Ho for critically reading the manuscript; Dr T. Otsuki for myeloma cell lines; Dr Yoshihisa Morishita; Dr Tetsuya Tsukamoto for gastric mucosa and Dr Yoshitoyo Kagami for primary leukemia cells; Dr Eisei Kondo and Dr Hidemasa Miyauchi for helpful discussion; Dr Keitaro Matsuo, Dr Hiroo Saji, Dr Etsuko Maruya, Dr Kazuhiro Yoshikawa, Ms Hisano Wakasugi, Ms Yumi Nakao, Ms Keiko Nishida, Dr Ayako Demachi-Okamura, and Ms Hiromi Tamaki for their expert technical assistance.

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C; no.17591025) and Scientific Research on Priority Areas (B01; no.17016089) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports, and Technology, Japan; Research on Human Genome, Tissue Engineering Food Biotechnology and the Second and Third Team Comprehensive 10-year Strategy for Cancer Control (no. 30) from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan; a Grant-in-Aid from Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) of Japan; Science and Technology Corporation (JST); Daiko Foundation; and Nagono Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: T.K., Y.A., and T.T. designed research; T.K., Y.A., and H.T. performed research; T.K., Y.A., S.O., and S.M. analyzed data; A.O., M.M., A.T., K.M., H.I., Y.M., and Y.K. contributed vital reagents or analytical tools; and T.K., Y.A., K.T., K.K., and T.T. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yoshiki Akatsuka, Division of Immunology, Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, 1-1 Kanokoden, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8681, Japan; e-mail: yakatsuk@aichi-cc.jp.