Abstract

Malarial anemia is a global public health problem and is characterized by a low reticulocyte response in the presence of life-threatening hemolysis. Although cytokines, in particular tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), can suppress erythropoiesis, the grossly abnormal bone marrow morphology indicates that other factors may contribute to ineffective erythropoiesis. We hypothesized that the cytotoxic hemozoin (Hz) residues from digested hemoglobin (Hb) significantly contribute to abnormal erythropoiesis. Here, we show that not only isolated Hz, but also delipidated Hz, inhibits erythroid development in vitro in the absence of TNF-α. However, when added to cultures, TNF-α synergizes with Hz to inhibit erythropoiesis. Furthermore, we show that, in children with malarial anemia, the proportion of circulating monocytes containing Hz is associated with anemia (P < .001) and reticulocyte suppression (P = .009), and that this is independent of the level of circulating cytokines, including TNF-α. Plasma Hz is also associated with anemia (P < .001) and reticulocyte suppression (P = .02). Finally, histologic examination of the bone marrow of children who have died from malaria shows that pigmented erythroid and myeloid precursors are associated with the degree of abnormal erythroid development. Taken together, these observations provide compelling evidence for inhibition of erythropoiesis by Hz.

Introduction

Severe malarial anemia (SMA) causes considerable global mortality and morbidity and may be the most common cause of years of lost life for a single hematologic disease. Despite the impact of this disease on the children and health services in the tropics, relatively little is known about the specific pathophysiology of malarial anemia.1 Understanding the pathophysiologic mechanism(s) whereby Plasmodium falciparum causes anemia is a prerequisite for developing effective means to prevent this condition.

SMA is defined as anemia (hemoglobin concentration [Hb] of < 50 g/L [5 g/dL]) with P falciparum asexual parasitemia, in the absence of any other or additional identifiable cause of anemia.2 In principle, all anemias are caused by disturbance in the balance between red cell production and loss. Malaria parasites destroy erythrocytes directly and also increase clearance of uninfected erythrocytes.3,4 A striking hematologic feature of the syndrome is the development of life-threatening hemolytic anemia with an inadequate reticulocyte response.5-8 The abnormalities of erythroid development are rapidly reversed by effective antimalarial drug therapy, and reticulocyte counts peak one week after treatment.6 Similar hematopathology has been described in several animal models of malaria.9-11 Low reticulocyte counts in acute infection and throughout chronic low-grade infection have been described in a simian model of falciparum malaria, where vaccination enabled control but not clearance of blood-stage parasites.12

The cause(s) of abnormal erythropoiesis in falciparum malaria is uncertain. Several studies have found an association between high circulating levels of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and SMA13,14 (reviewed in McDevitt et al15 ). However, suppression of erythropoiesis in vitro occurs only at levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ well above those observed in clinical studies. Furthermore, cytokine-mediated suppression of erythropoiesis is not associated with gross morphologic abnormalities of erythroid development.16 In patients with falciparum malaria, examination of the bone marrow shows profoundly abnormal morphology of erythroid precursors, including karyorrhexis and cytoplasmic and nuclear bridging.7,8 Abnormal development of erythroid precursors becomes more marked in chronic infections when proinflammatory cytokines are declining.8 Other cytokines may ameliorate anemia. Raised plasma concentrations of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-12p70 have been shown to be associated with higher Hb concentrations during acute malarial infection.13,17

Malaria parasites digest Hb as they grow within erythrocytes, and insoluble heme residues are polymerized into malaria pigment or Hz.18,19 Hz has been implicated previously as a direct or indirect cause of widespread cellular dysfunction. We hypothesized that the toxic effects of Hz may also directly or indirectly inhibit erythropoiesis.

We therefore developed a serum-free model of erythropoiesis to study the effect of malaria-infected erythrocytes (IEs) and purified Hz on erythropoiesis in vitro. We went on to examine the relationship between anemia and reticulocyte suppression with free and intraleukocytic Hz in children with malaria. Finally, we studied the association of Hz and dyserythropoietic changes in the bone marrow of children who had died from malaria. We show that Hz is capable of directly inhibiting erythropoiesis in vitro and that, in children with malaria, the presence of Hz whether in circulation (plasma and leukocytes) or in the bone marrow (erythroid and myeloid precursors) is associated with anemia and with abnormal erythropoiesis.

Patients, materials, and methods

Cultivation of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes

The P falciparum (ITO4/A4) laboratory clone was cultured in erythrocytes as previously described.20,21 All cultures used in experiments were negative for Mycoplasma spp by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for species-specific sequences (Mycoplasma Detection Kit; ATCC, Manassas, VA). Trophozoite stages of P falciparum cultures were enriched to more than 90% purity using a magnet (see Document S1 for full description, available at the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Preparation and measurement of Hz

Crude parasite lysate and Hz were prepared from trophozoite-enriched cultures by freeze-thaw of infected erythrocytes and density gradient centrifugation as described by Schwarzer et al.22 The different batches of Hz were quantified according to the release of monomeric heme in mild alkaline conditions as described by Sullivan et al.23 In brief, heme was released from all samples under mild alkaline conditions (Tris HCl [pH 8], 20 mM NaOH) and measured by spectrophotometry (A405).23 Hz, unlike heme-containing proteins, sediments at 10 000g. Therefore, plasma Hz concentrations were calculated as the difference of plasma heme released before and after centrifugation of plasma (see Document S1 for full description).

Delipidation of Hz

Hz was delipidated as previously described.24 Delipidation was carried out twice in order to ensure the complete removal of lipids. Hz was collected from the chloroform-methanol interphase and washed 5 times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The Hz suspension was sonicated and quantified as described in “Preparation and measurement of Hz.”

Isolation of CD34+ cells and culture conditions

CD34+ progenitor cells were obtained from umbilical cord blood collected after normal deliveries at the John Radcliffe Hospital (Oxford, United Kingdom) with informed consent and ethics approval. Light-density mononuclear cells were obtained by centrifugation on Ficoll-Hystopaque-1.077 (Sigma Chemical, Poole, United Kingdom). The mononuclear cell fraction was enriched for CD34+ cells by positive selection using CD34 antibody and immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Surrey, United Kingdom). Purity was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence with CD34-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson, Sunnyvale, CA) as previously described.25 All isolations had CD34 cell purity more than 95%. CD34+-enriched cells were cultured in serum-free StemBio A medium (Nova Stem, Villejuif, France) with Epo (1 U/mL), IL-3 (20 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL), and stem cell factor [SCF] 100 ng/mL) (all from R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom). These conditions had been optimized prior to these studies (S.M.W. and J.O.P.C., unpublished data, June 2002). This model of erythroid development has some advantages over BFU-e or CFU-e assays because it is possible to assess the growth and phenotype of developing cells continuously rather than at fixed points. In addition, the culture medium is serum free and therefore more reproducible than assays that require serum. However, a serum-free model is likely to underestimate the effect of Hz on erythroid proliferation (Figure S1). Cells were grown in 24-well plates with an initial seeding density of 50 000 cells/mL or in 96-well plates with an initial seeding density of 5000 cells/mL with regular addition of cytokines. Cells were expanded for 14 days at 37°C with 5% CO2 in air. Viable cell counts were performed by trypan blue dye exclusion at days 0, 4, 7, 11, and 14, and cellular phenotypes were determined using flow cytometry.

Hemozoin or intact or lysed P falciparum-infected erythrocytes (late trophozoite stage) were added to erythroid cultures on days 0, 4, and 7 and cocultured for up to 11 days. Cultures were mixed daily using a sterile pipette. TNF-α and α-hematin were used as positive controls for the inhibition of erythroid expansion by cytokines and oxidative stress, respectively. We have used α-hematin equivalents as our standard for Hz quantitation. Therefore, the effect of α-hematin in the cultures added a biologic or functional significance to the quantitation of Hz in hematin equivalents.

Antibody labeling and flow cytometry

The expression of cell surface markers was studied by indirect immunofluorescence staining. Monoclonal antibodies were used as described in Document S1. The proportion of positively stained cells and their median fluorescence intensities were obtained by flow cytometry and analyzed with CellQuest Pro Software (Becton Dickinson) or WinMDI (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA).

Patients, study site, and recruitment

The clinical study was undertaken at Kilifi District Hospital (KDH), Kenya. The epidemiology of malaria in Kilifi District has been described elsewhere.26 The average annual entomologic inoculation rate (EIR) in Kilifi is under 5 infective bites per person per year.27 The study was completed between October 2001 and September 2002. Consecutive children aged 6 months to 10 years attending the outpatient clinic were screened for fever (> 38.5°C), anemia, and P falciparum parasitemia. Children with fever and any P falciparum parasitemia were allocated to the following study groups according to Hb concentration: 30 children with severe malarial anemia (Hb < 50 g/L [5.0 g/dL]); 30 children with moderate malarial anemia (Hb, 50-69 g/L [5.0-6.9 g/dL]); 30 children with mild malarial anemia (Hb, 70-99 g/L [7.0-9.9 g/dL]); and 30 children with malaria and Hb higher than 100 g/L (10 g/dL). A history of prior treatment with antimalarials during the week before admission was an exclusion criterion.

Screening was performed on capillary samples. Hb concentrations were slightly different between capillary samples and venous samples. In 8 cases, such discrepancies resulted in allocation to a different study group. In these cases, group allocation was based on the Hb concentration in the venous sample. There was not a consistent pattern of loss of follow-up for a specific group.

A 3-mL venous blood sample was collected into EDTA tubes and processed immediately. A full blood count was obtained by a hematology analyzer (Coulter MD II; Coulter, Miami, FL). Peripheral blood films were stained with 3% May-Grünwald-Giemsa and also stained with New Methylene Blue to count reticulocytes. A Miller Graticule (Canemco & Marivac, Quebec, Canada) was used to improve the accuracy of reticulocyte counts, enabling the number of reticulocytes per 4500 red blood cells (RBCs) to be recorded.28 Absolute parasite counts were calculated for each child using either thin films (counting parasitized RBCs per 500 RBCs) or thick films (counting parasitized RBCs per 200 white blood cells [WBCs]). The number of Hz-containing monocytes (HCMs) per 500 monocytes and Hz-containing neutrophils (HCNs) per 500 neutrophils was counted from Giemsa-stained thick films. Monocytes or neutrophils containing more than 2 inclusions of Hz were defined as Hz-containing cells. The technicians performing counts of Hz-containing cells or reticulocytes were blinded to the identity of the patients, the case history, and the Hb value or other laboratory variables. Direct Coombs test was performed using a commercial kit (DiaMed, Midlothian, United Kingdom). HIV 1/2 antibodies were tested anonymously by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Abbott Laboratories, United Kingdom). Plasma cytokines were measured by ELISA Quantikine kits (R&D Systems).

Children with malaria were treated according to the Unit's guidelines (see Document S1 for full details). Children were followed up and examined 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months after being recruited. Full blood, parasite, and reticulocyte counts were obtained. A field worker visited all children who did not come to any of the follow-up visits to check the reasons for nonattendance. At 3 months, all children recruited in our study were alive and 1 had migrated from the study area.

Plasma samples from a group of 20 children with anemia (Hb, between 75-100 g/L [7.5-10 g/dL]) and no malaria (negative blood slide for P falciparum) were used to obtain baseline data on erythropoietin (Epo) and soluble transferrin receptor (sTFR).

Postmortem studies

Samples of bone marrow from the vertebral bodies were prepared from children enrolled in the on-going study of the pathology of cerebral malaria in Blantyre, Malawi29 (see Document S1 for full details). The number of pigmented and nonpigmented erythroid and nonerythroid cells was quantified counting 10 high-power fields of at least 600 cells (median, 670 cells) in each section. A cell was considered pigmented if a clearly visible Hz dot was either inside or in contact with the cell surface. The proportion of erythroid cells with multi-, bi-, or grossly irregular nuclei was also recorded and counted as abnormal erythroid cells.

Ethics considerations

The involvement of human subjects, their samples, and their data were compliant with the guidelines provided by the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2000) and were approved by the National Ethical Committee of Kenya, the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee, Malawi, and the Ethics Committee of the University of Liverpool. Informed consent was obtained from the guardians/parents in their own language (see Document S1 for details).

Statistical analyses

Independent t tests or Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare means between independent groups as appropriate, setting the level of significance at α equal to .05. Where more than one group was compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the nonparametric equivalent (Kruskal-Wallis test), a new level of significance was set at α divided by the number of comparisons.

This study was designed to confirm that in children with anemia and malaria there is an ineffective reticulocyte response and to test the hypothesis that Hz (both in plasma and circulating leukocytes) is associated with anemia (measured by the Hb concentration on admission) and with ineffective reticulocyte response (measured by the difference in absolute reticulocyte counts on admission and one week after treatment). Therefore, Hb and the reticulocyte response were used as the main dependent variables in the regression models (see Document S1 for further details) (SPSS 11.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Inhibition of erythroid expansion by intact and lysed infected erythrocytes (IEs)

We mixed intact cytoadherent IEs or lysed IEs from the laboratory clone ITO4/A4 (which can bind to CD36, ICAM-1, and TSP) or uninfected erythrocytes (UEs) with isolated CD34+ progenitor cells on day 0 or day 4 after induction of erythroid development. Both intact and lysed IEs inhibited erythroid expansion by up to 50% compared with control wells containing either cells or lysate (Table 1). The effect was maximal when cells and lysate were added on day 4, and here intact and lysed IEs inhibited erythroid growth to a mean of 45.4% and 55.6%, respectively, compared with controls containing no IEs or lysate. Inhibition of erythroid growth by a lysate of IEs added on day 7 was also significant (Table 1).

Inhibition of erythroid expansion by infected erythrocytes (IE), IE lysate, TNF-α, uninfected erythrocytes (UEs), and UE lysate

Time of cell, cytokine, or lysate addition/day of measurement of growth inhibition . | IEs, % of control (SD) . | IE lysate, % of control (SD) . | TNF-α (30 ng/mL),*% of control (SD) . | UEs, % of control (SD) . | UE lysate,†% of control (SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | |||||

| Day 11 | 73.9 (12.6)‡ | 63.7 (26.3)§ | 78.2 (9.9)‡ | 82.2 (6.39) | 89.5 (7.21) |

| Day 14 | 67.3 (26.2)§ | 55.9 (30.9)§ | 71.5 (22.6)‡ | 90.6 (5.4) | 84.9 (1.9)‡ |

| Day 4* | |||||

| Day 11 | 45.4 (27.7)‡ | 55.6 (32.5)‡ | 74.8 (12.9)‡ | 90.4 (15.3) | 111.7 (22.0) |

| Day 14 | 61.1 (38.5)‡ | 58.5 (37.8)‡ | 93.2 (26.3) | 91.8 (9.3) | 110.9 (8.3) |

| Day 7† | |||||

| Day 11 | 79 (10.3) | 82 (0.9)|| | 80.3 (8.3)‡ | ND | ND |

| Day 14 | 92.6 (10.8) | 98.7 (5.07) | 98.5 (8.5) | ND | ND |

Time of cell, cytokine, or lysate addition/day of measurement of growth inhibition . | IEs, % of control (SD) . | IE lysate, % of control (SD) . | TNF-α (30 ng/mL),*% of control (SD) . | UEs, % of control (SD) . | UE lysate,†% of control (SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | |||||

| Day 11 | 73.9 (12.6)‡ | 63.7 (26.3)§ | 78.2 (9.9)‡ | 82.2 (6.39) | 89.5 (7.21) |

| Day 14 | 67.3 (26.2)§ | 55.9 (30.9)§ | 71.5 (22.6)‡ | 90.6 (5.4) | 84.9 (1.9)‡ |

| Day 4* | |||||

| Day 11 | 45.4 (27.7)‡ | 55.6 (32.5)‡ | 74.8 (12.9)‡ | 90.4 (15.3) | 111.7 (22.0) |

| Day 14 | 61.1 (38.5)‡ | 58.5 (37.8)‡ | 93.2 (26.3) | 91.8 (9.3) | 110.9 (8.3) |

| Day 7† | |||||

| Day 11 | 79 (10.3) | 82 (0.9)|| | 80.3 (8.3)‡ | ND | ND |

| Day 14 | 92.6 (10.8) | 98.7 (5.07) | 98.5 (8.5) | ND | ND |

Inhibition is expressed as percentage of expansion of control cultures after 11 and 14 days of culture without added medium, cells, or TNF-α

Uninfected red blood cells (UE), infected erythrocytes (IE), and their respective lysates were added at a ratio of 1 developing erythroid cell per 50 UEs or IEs or their lysates. The mean and SD were calculated from 7 independent experiments unless specified otherwise

ND indicates not done on day 7 cultures

N = 5

N = 3

P < .05 compared with control wells

P < .01 compared with control wells

P < .001 compared with control wells

The reduction of erythroid expansion was not significantly greater by intact infected cells when compared with lysed infected cells, so excluding a metabolic effect of viable infected cells on developing erythroid cells. Similar results were obtained after the addition of infected erythrocytes from a cytoadherent parasite line (ITO/A4) and from a nonadherent line (T9/96) to erythroid cultures (data not shown). This suggested that adherence of infected cells to erythroid precursors did not in itself reduce growth. We concluded that lysed IEs were sufficient to produce a maximal inhibitory effect. We titrated the effect of a lysate of IEs and showed that significant inhibition of erythropoiesis occurred down to a ratio of a lysate of 10 IEs to one erythroid precursor (Figure 1A).

Inhibition of erythroid growth by Hz

We purified Hz from infected cells and titrated the effect of Hz on erythroid expansion. Purified Hz inhibited erythropoiesis to a similar degree to the corresponding amount of crude lysate of IEs (Figure 1B). Inhibition was significant at concentrations of Hz similar to that estimated to be present in circulation in severe malaria, namely 1 to 10 μg/mL (see “Measurement of Hz in plasma” and Keller et al30 ). At concentrations of 10 μg/mL, β-hematin (synthetic malarial pigment) and α-hematin produced a similar inhibition on erythroid expansion (Figure 1C and 1D, respectively). The inhibition of erythropoiesis produced by Hz was similar to that produced by the equivalent concentration of α-hematin (Figure 1B,D).

Inhibition of erythroid growth and cytokines

TNF-α has been associated with malarial anemia and has been suggested as a cause of inadequate erythropoiesis. In our model system, we were able to show inhibition of erythropoiesis at TNF-α concentrations more than 3 ng/mL (Figure 1E). However, after addition of lysate of IEs or purified Hz to developing erythroid cells, TNF-α remained undetectable (ie, levels of TNF-α were < 32 pg/mL, the lower limit of detection in our assays). Moreover, whereas the inhibitory effect of TNF-α was reversed with anti-TNF-α antibodies (infliximAb, 50 μg/mL), the effect of Hz remained unchanged (Figure S2). Therefore, in this model the inhibition of erythroid growth by lysed IEs or purified Hz appeared to be independent of TNF-α.

Inhibition of erythroid expansion. Lysate of infected erythrocytes (IE lysate) (A), hemozoin (Hz) (B), β-hematin (C), α-hematin (D), and TNF-α (E) were added at the stated ratios/concentrations to developing erythroid cells on day 4. Erythroid expansion was measured on days 7 and 11. The columns represent mean inhibition of erythroid expansion compared with control wells containing medium without added cells or lysate. The error bars show the SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Inhibition of erythroid expansion. Lysate of infected erythrocytes (IE lysate) (A), hemozoin (Hz) (B), β-hematin (C), α-hematin (D), and TNF-α (E) were added at the stated ratios/concentrations to developing erythroid cells on day 4. Erythroid expansion was measured on days 7 and 11. The columns represent mean inhibition of erythroid expansion compared with control wells containing medium without added cells or lysate. The error bars show the SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Inhibition of erythroid development by Hz and cytokines

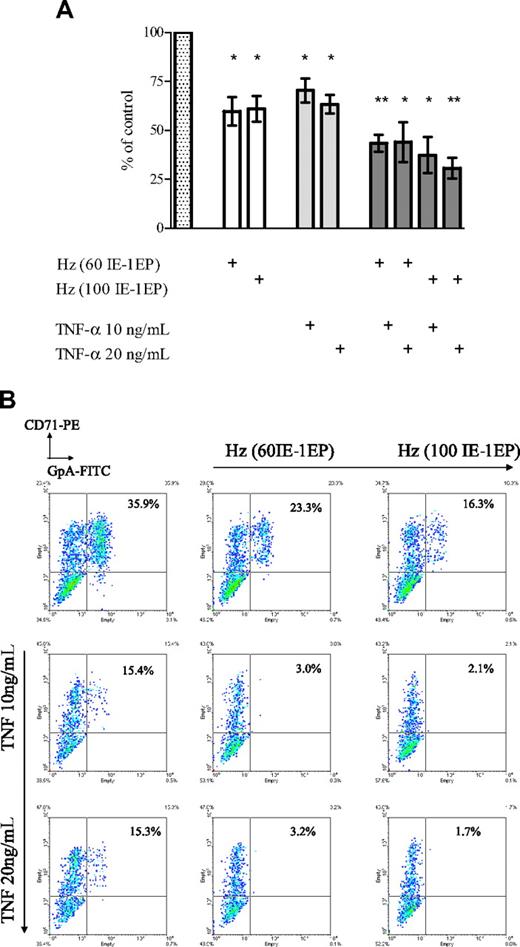

In patients with malaria, high concentrations of TNF-α have been associated with severe disease. Our experimental results also showed inhibition of erythroid development by purified Hz. We therefore exposed developing erythroid cells to different concentrations of both Hz and TNF-α to determine if they produced additive inhibitory effects on growth and development. Purified Hz (50, 100, and 200 IE equivalents per erythroid cell) and TNF-α at concentrations of 10 and 20 ng/mL produced additive inhibition not only of erythroid growth (Figure 2A), but also of erythroid development, as determined by cells coexpressing CD71 and glycophorin A (GpA) after 11 days of culture (Figure 2B). These results suggest that Hz and TNF-α have independent inhibitory effects on the development of erythroid cells. We therefore examined the association of these effectors on anemia and the reticulocyte response in children with falciparum malaria.

Delipidation of Hz

Hemozoin could inhibit the growth and maturation of erythroid cells by a direct effect of β-hematin. It has also been suggested that inhibition may, at least in part, be mediated by biologically active lipids generated by Hz-fed monocytes.54 We therefore compared the inhibitory effect of crude and delipidated Hz (both at 10 μg/mL) on erythroid development. Both crude and delipidated Hz inhibited growth compared with control cultures, at 37.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 25.0%-49.2%) and 26.2% (95% CI, 14.0%-38.2%), respectively (P < .001, in each case). The difference between inhibition by crude Hz and delipidated Hz was not significant (P > .05).

Effect of Hz and TNF-α added at different concentrations on erythroid expansion and phenotype in erythroid cultures. (A) Cell expansion was measured at day 11. The bars represent mean inhibition of erythroid expansion compared with control wells containing medium (dotted bar). The error bars show the SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01. (B) Cells were stained with CD71-PE and GpA-FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry. These plots correspond to a representative experiment.

Effect of Hz and TNF-α added at different concentrations on erythroid expansion and phenotype in erythroid cultures. (A) Cell expansion was measured at day 11. The bars represent mean inhibition of erythroid expansion compared with control wells containing medium (dotted bar). The error bars show the SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01. (B) Cells were stained with CD71-PE and GpA-FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry. These plots correspond to a representative experiment.

Study population

We recruited consecutive children presenting with fever and any parasitemia into 4 groups with Hb concentrations of less than 50 g/L (5.0 g/dL), 50 to 69 g/L (5.0-6.9 g/dL), 70 to 99 g/L (7.0-9.9 g/dL), and more than 100 g/L (10 g/dL). The age, sex, and observed parasite density in the peripheral blood were comparable in all 4 groups (Table 2). Two children were positive for HIV 1/2 antibodies. Ten children required blood transfusions. None of the children died during the follow-up period, and 1 month after treatment children had recovered from anemia and the mean Hb concentration did not differ among the groups.

Characteristics of the clinical study population

Characteristic . | Group 1 . | Group 2 . | Group 3 . | Group 4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 29 | 24 | 37 | 30 |

| Mean age, y (SD) | 2.8 (2.6) | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.7 (1.8) | 3.8 (2.1) |

| Male-female ratio | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Mean weight-for-age Z-score (SD) | –2.4 (1.2) | –1.7 (1.6) | –1.7 (1.0) | –1.1 (1.7) |

| Mean Hb level, g/L (SD) | 40 (6) | 60 (4) | 82 (8) | 110 (7) |

| Mean HCT (SD) | .129 (.02) | .195 (.015) | .261 (.024) | .340 (.024) |

| Mean MCV, fL (SD) | 67.5 (8.1) | 69.1 (8.9) | 66.6 (7.6) | 73.5 (6.9) |

| Mean MCH, pg (SD) | 21.4 (3.6) | 21.4 (3.2) | 21.0 (2.9) | 23.8 (2.4) |

| Median reticulocyte count on admission, × 109/L (IQR) | 47.2 (24.8-58.7) | 56.2 (18.4-106.3) | 42.4 (20.2-62.5) | 23.8 (15.4-34.7) |

| Median reticulocyte count at 1 week, × 109/L (IQR) | 216.4 (129.3-358.6) | 294.0 (125.1-365.8) | 153.6 (111.0-218.5) | 55.8 (39.3-84.8) |

| Median P falciparum count, × 103/μL (IQR) | 25.5 (0.6-119) | 10.6 (4.2-96.3) | 14.2 (3.2-147) | 10.3 (2.1-28.2) |

| Median erythropoietin level, mU/mL (IQR) | 5033 (3117-5955) | 1473 (343.5-3114) | 152 (67-252) | 40.4 (5.3-74.3) |

| Coombs test positive, % | 34.5 | 41.7 | 37.8 | 26.7 |

Characteristic . | Group 1 . | Group 2 . | Group 3 . | Group 4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 29 | 24 | 37 | 30 |

| Mean age, y (SD) | 2.8 (2.6) | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.7 (1.8) | 3.8 (2.1) |

| Male-female ratio | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Mean weight-for-age Z-score (SD) | –2.4 (1.2) | –1.7 (1.6) | –1.7 (1.0) | –1.1 (1.7) |

| Mean Hb level, g/L (SD) | 40 (6) | 60 (4) | 82 (8) | 110 (7) |

| Mean HCT (SD) | .129 (.02) | .195 (.015) | .261 (.024) | .340 (.024) |

| Mean MCV, fL (SD) | 67.5 (8.1) | 69.1 (8.9) | 66.6 (7.6) | 73.5 (6.9) |

| Mean MCH, pg (SD) | 21.4 (3.6) | 21.4 (3.2) | 21.0 (2.9) | 23.8 (2.4) |

| Median reticulocyte count on admission, × 109/L (IQR) | 47.2 (24.8-58.7) | 56.2 (18.4-106.3) | 42.4 (20.2-62.5) | 23.8 (15.4-34.7) |

| Median reticulocyte count at 1 week, × 109/L (IQR) | 216.4 (129.3-358.6) | 294.0 (125.1-365.8) | 153.6 (111.0-218.5) | 55.8 (39.3-84.8) |

| Median P falciparum count, × 103/μL (IQR) | 25.5 (0.6-119) | 10.6 (4.2-96.3) | 14.2 (3.2-147) | 10.3 (2.1-28.2) |

| Median erythropoietin level, mU/mL (IQR) | 5033 (3117-5955) | 1473 (343.5-3114) | 152 (67-252) | 40.4 (5.3-74.3) |

| Coombs test positive, % | 34.5 | 41.7 | 37.8 | 26.7 |

Children were recruited into each group based on the Hb level in the screening test, namely group 1 (Hb, < 50 g/L [5.0 g/dL]), group 2 (Hb, 50-69 g/L [5.0-6.9 g/dL]), group 3 (Hb, 70-99 g/L [7.0-9.9 g/dL]), and group 4 (Hb, 100 g/L [10.0 g/dL] or greater). In the final analysis, the group sizes differed slightly as the measurement of hemoglobin in the outpatient department, where most patients were recruited, differed from the measurement of hemoglobin by the regularly calibrated Coulter counter

The children in the control group (Hb, > 100 g/L [10 g/dL]) had a better nutritional status and were older than children with anemia, but these differences were not significant. There was no evidence of an association between parasite density and Hb concentration (P = .7). Epo concentrations were strongly associated with Hb levels (r = -0.82, P < .001). Plasma levels of Epo in children with mild anemia (mean Hb, 98 g/L [9.8 g/dL]; SD, 14 g/L [1.4 g/dL]) and malaria were 3.5 times higher than those of a group of 20 children with mild to moderate anemia (mean Hb, 95 g/L [9.5 g/dL]; SD, 9 g/L [0.9 g/dL]) but without malaria (median, 63.59; interquartile range [IQR], 24.8-148.6 IU/L [mU/mL]; and median, 18.2; IQR, 31-6.5 IU/L [mU/mL], respectively) (P < .001). These findings suggested that Epo secretion was adequate to the degree of anemia.

We did not find any association between a positive direct Coombs test and the degree of anemia (P = .52). However, children who had malaria but were not anemic (Hb, > 100 g/L [10 g/dL]) were less likely to have a positive direct Coombs test than anemic children with malaria and Hb concentration less than 100 g/L (10 g/dL) (26% vs 39%, P < .01) (Table 2).

Anemia and reticulocyte suppression

The absolute reticulocyte counts were greater in anemic than in nonanemic children (P < .01). However, the reticulocyte counts in children presenting with acute falciparum malaria and anemia were much lower than would be expected if the bone marrow was responding appropriately. One week after treatment, the reticulocyte counts increased in all groups between 3- and 5-fold compared with the counts on admission. The difference in absolute reticulocyte counts before treatment and 1 week after treatment was associated with the degree of anemia (P < .001) (Figure 3).

Blood transfusion on admission appeared to suppress the reticulocyte response at 1 week. Ten children with severe anemia in group 1 who were transfused showed lower reticulocyte counts at 1 week after treatment (164 × 109/L; 95% CI, 89 × 109-239 × 109/L) than those who were not transfused (279 × 109/L; 95% CI, 181 × 109-377 × 109/L). This difference was of borderline significance (P = .06) and, therefore, those children were not excluded from the analysis.

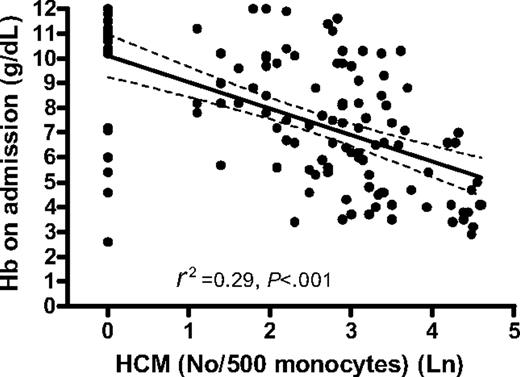

Anemia and circulating Hz

Hemozoin is cleared slowly from the circulation and thus Hz-containing leukocytes may reflect not only the total amount of Hz produced during infection but also the deposition of Hz in the bone marrow and erythroid precursors. We therefore determined the relationship between anemia and the reticulocyte response and circulating Hz-containing leukocytes. The degree of anemia in children with falciparum malaria was strongly related to the proportion of circulating Hz-containing monocytes (HCMs) (R2 = 0.29, P < .001) (Figure 4) and Hz-containing neutrophils (HCNs) (P < .01). The association between Hb concentration after a month and proportion HCMs and HCNs at this time was also significant (P < .001 and P < .01, respectively). The absolute number of HCMs and HCNs showed similar negative associations with Hb concentration on admission (data not shown).

In the regression analysis, 6 children with moderate to severe anemia departed from the main regression line. All except one of these children had very low MCV values compared with nonoutliers (mean [SD]: 61.7 fL [8.9] and 71 fL [8.1], respectively), and the reticulocyte response 1 week after malaria treatment was still low in all 6 cases, suggesting that the underlying cause of anemia was not malaria.

Anemia and pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines

We also examined the association between anemia and the cytokines TNF-α, IL-10, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ thought to contribute to the degree of anemia in children with falciparum malaria. All these independent variables, with the exception of TNF-α, were associated with Hb concentration on admission in the univariate analysis. However, only HCMs and IL-10 were significantly associated with Hb concentration on admission in the multiple linear regression analysis (Table 3).

Multiple regression analyses for the parasitologic and immunologic variables on admission

Independent variables . | Slope, B . | 95% CI, B . | β . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. HCMs/500 monocytes, In | –1.06 | –1.39-–0.74 | –0.54 | < .001 |

| IL-10, In concentration | 0.71 | 0.38-1.05 | 0.33 | .004 |

Independent variables . | Slope, B . | 95% CI, B . | β . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. HCMs/500 monocytes, In | –1.06 | –1.39-–0.74 | –0.54 | < .001 |

| IL-10, In concentration | 0.71 | 0.38-1.05 | 0.33 | .004 |

The independent variables included were hemozoin-containing monocytes (HCMs, as number per 500 monocytes), hemozoin-containing neutrophils (HCNs, as number per 500 neutrophils), and the concentration of cytokines TNF-α, IL-10, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ. The variables showing a significant association with Hb in the univariate analysis were entered into the multiple linear regression analysis. We show the direct value of the slope (B), the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the slope, and the standardized value of the slope (β) for the variables significantly associated with the dependent variables in the multiple regression analyses. In indicates logarithm Neperian

Ineffective erythropoiesis and Hz

The difference between the absolute reticulocyte count after one week and the count on admission is an indirect measure of the degree of the suppression of reticulocyte production or ineffective erythropoiesis. We therefore used the rise in reticulocyte count from admission to 1 week later as a variable to explore the association between ineffective erythropoiesis and relevant parasitologic and immunologic factors that could inhibit the reticulocyte response. HCMs, HCNs, and the levels of the TNF-α, IL-10, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ were included in the univariate and multiple linear regression analyses using the reticulocyte difference between one week and at presentation as the dependent variable.

In the univariate analysis, only HCMs (P = .001), HCNs (P = .004), and TNF-α (P = .008) were linearly associated with reticulocyte suppression. When these variables were included in multiple regression analysis, only HCMs and TNF-α remained in the model (Table 4). These analyses suggest that the proportion of HCMs has a greater effect on reticulocyte suppression than the levels of TNF-α and that these effects are independent.

Multiple regression analyses of the parasitologic and immunologic variables for reticulocyte response

Independent variables . | Slope, B . | 95% CI, B . | β . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. HCMs/500 monocytes, In | 0.27 | 0.07-0.47 | 0.30 | .009 |

| TNF-α, log concentration | 0.30 | 0.04-0.56 | 0.23 | .02 |

Independent variables . | Slope, B . | 95% CI, B . | β . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. HCMs/500 monocytes, In | 0.27 | 0.07-0.47 | 0.30 | .009 |

| TNF-α, log concentration | 0.30 | 0.04-0.56 | 0.23 | .02 |

The independent variables included were hemozoin-containing monocytes (HCMs, as number per 500 monocytes), hemozoin-containing neutrophils (HCNs, as number per 500 neutrophils), and the concentration of cytokines TNF-α, IL-10, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ. The variables showing a significant association with reticulocyte difference in the univariate analysis were entered into the multiple linear regression analysis. We show the direct value of the slope (B), the 95% confidence inteval (95% CI) of the slope, and the standardized value of the slope (β) for the variables significantly associated with the dependent variables in the multiple regression analyses

Difference in the reticulocyte counts before and after treatment in children with acute malarial anemia. The mean absolute reticulocyte counts (× 109/L) on admission and one week after treatment in children with severe anemia (Hb, < 50 g/L [5 g/dL]), moderate anemia (Hb, 50-69 g/L [5-6.9 g/dL]), mild anemia (Hb, 70-100 g/L [7-10 g/dL]), and no anemia (Hb, > 100 g/L [10 g/dL]). The bars show the mean values; error bars, 95% CI.

Difference in the reticulocyte counts before and after treatment in children with acute malarial anemia. The mean absolute reticulocyte counts (× 109/L) on admission and one week after treatment in children with severe anemia (Hb, < 50 g/L [5 g/dL]), moderate anemia (Hb, 50-69 g/L [5-6.9 g/dL]), mild anemia (Hb, 70-100 g/L [7-10 g/dL]), and no anemia (Hb, > 100 g/L [10 g/dL]). The bars show the mean values; error bars, 95% CI.

We did not use derived ratios of cytokines in our analysis, but if IL-10 and TNF-α were replaced by the IL-10/TNF-α ratio then this variable was significantly associated with both Hb on admission (P < .001) and reticulocyte suppression (P = .003) in the univariate analysis. In the multiple regression analyses, the IL-10/TNF-α ratio was significantly associated with Hb on admission (P < .01) but did not reach significance (P = .059) when reticulocyte suppression was used as the dependent variable.

Measurement of Hz in plasma

Hemozoin in plasma was measured in all but 5 of the admission samples (in these 5, the volume of plasma left was insufficient). These 5 cases did not come from any specific group. The concentration of plasma Hz in moderately and severely anemic children (Hb, < 69.9 g/L [6.99 g/dL])—4.5 (1.8-10.9) μg/mL—was significantly higher than the concentration in children with Hb concentration more than 70 g/L (7.0 g/dL)—2.7 (0.57-5.8) μg/mL (median [IQR]; Mann-Whitney, P = .01).

The plasma Hz concentration was significantly associated with HCMs (r = 0.34, P < .001) and HCNs (r = 0.26, P = .004), but neither with P falciparum parasite density (P = .3) nor with plasma concentrations of TNF-α (P = .15), IFN-γ (P = .37), IL-12 (P = .54), or IL-10 (P = .23). Plasma Hz was determined in 107 samples a week after treatment. The median (IQR) concentration was 0.83 (0-5.5) μg/mL.

Association between Hb concentration on admission (in grams per deciliter) and number of hemozoin-containing monocytes per 500 monocytes. The graph shows the regression line (solid) and the 95% CI of the regression line (dashed).

Association between Hb concentration on admission (in grams per deciliter) and number of hemozoin-containing monocytes per 500 monocytes. The graph shows the regression line (solid) and the 95% CI of the regression line (dashed).

Plasma Hz concentration was associated with lower Hb concentrations (r = -0.303, P = .001) and higher degrees of reticulocyte suppression (r = 0.22, P = .02). Similar results were found in the univariate regression analyses with both Hb and reticulocyte suppression. In the multiple regression analyses, plasma Hz concentration independently increased the predictability of reticulocyte suppression (data not shown).

Histopathology

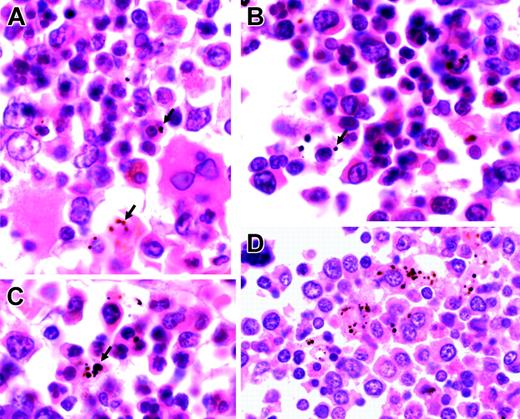

We examined 17 sections of postmortem bone marrow trephines from Malawian children who had died with malaria. All children with patent parasitemia had plentiful pigmented myeloid and erythroid cells (Figure 5; Table 5). The numbers of pigmented erythroid and nonerythroid cells per high-power field were associated with each other (r = 0.60, P = .01), and both were associated with the number of abnormal (bi-, multi-, or irregularly nucleated) erythroid precursors (erythroid: r = 0.62 and P < .008; and nonerythroid: r = 0.54 and P < .02). The number of normal erythroid cells was associated with hematocrit (r = 0.50, P = .04).

Characteristics of the postmortem study population

Characteristic . | Median value (IQR) . |

|---|---|

| Age, mo | 35 (19-48) |

| P falciparum count/μL | 73 806 (788.5-302 400) |

| Hematocrit | 0.15 (0.12-0.30) |

| Normal erythroid, % of total cells* | 9.2 (5.7-16.8) |

| Abnormal erythroid, % of total cells* | 18.1 (9.3-23.5) |

| Fraction of abnormal erythroid, % of total erythroid cells* | 60 (55-69) |

| Myeloid, % of total cells* | 59.3 (49-76.9) |

| Erythroid with Hz, % of total cells* | 2.1 (0.78-2.7) |

| Myeloid with Hz, % of total cells* | 5.7 (4.3-7.9) |

Characteristic . | Median value (IQR) . |

|---|---|

| Age, mo | 35 (19-48) |

| P falciparum count/μL | 73 806 (788.5-302 400) |

| Hematocrit | 0.15 (0.12-0.30) |

| Normal erythroid, % of total cells* | 9.2 (5.7-16.8) |

| Abnormal erythroid, % of total cells* | 18.1 (9.3-23.5) |

| Fraction of abnormal erythroid, % of total erythroid cells* | 60 (55-69) |

| Myeloid, % of total cells* | 59.3 (49-76.9) |

| Erythroid with Hz, % of total cells* | 2.1 (0.78-2.7) |

| Myeloid with Hz, % of total cells* | 5.7 (4.3-7.9) |

N = 17

Irregular nuclei, binuclear, and multinuclear erythroid cells

Discussion

A low reticulocyte response in the face of severe hemolysis is one of the most striking features of severe malarial anemia in humans, nonhuman primates, and rodents (reviewed in Roberts et al31 ). The cause of this inadequate reticulocyte response in falciparum malaria remains uncertain. Proinflammatory cytokines, in particular TNF-α, have been thought to be the major cause of bone marrow dysfunction.32 However, our experimental data show for the first time that Hz directly inhibits erythropoiesis independently from TNF-α, and that Hz and TNF-α have additive effects on thedevelopment of erythroid cells. In children with malaria, we have shown that circulating free and intraleukocytic Hz is associated with anemia and ineffective erythropoiesis and crucially that this association is independent of levels of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ. Finally, our histologic studies show an association between pigmented erythroid and myeloid cells in the bone marrow and the number of abnormal erythroid precursors.

Representative sections of bone marrow from children with severe malarial anemia. (A-C) Highly abnormal erythropoiesis (irregular, bi-, and multinucleated erythroid cells) in association with Hz (arrows). (D) Hz predominantly inside myeloid cells (hematoxylin and eosin staining; original magnification, × 1000). Cells were viewed with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a Nikon 100 ×/1.40 numeric aperture oil-immersion objective lens (Nikon, Surrey, United Kingdom) and a Zeiss Axiocam (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). Axiovision 3 software (Zeiss) was used to acquire images, and ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) was used to process them.

Representative sections of bone marrow from children with severe malarial anemia. (A-C) Highly abnormal erythropoiesis (irregular, bi-, and multinucleated erythroid cells) in association with Hz (arrows). (D) Hz predominantly inside myeloid cells (hematoxylin and eosin staining; original magnification, × 1000). Cells were viewed with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a Nikon 100 ×/1.40 numeric aperture oil-immersion objective lens (Nikon, Surrey, United Kingdom) and a Zeiss Axiocam (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). Axiovision 3 software (Zeiss) was used to acquire images, and ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) was used to process them.

Our initial experimental studies were prompted by the long-standing observations of low reticulocyte response in children suffering from SMA. In 1939, Vryonis first observed that the numbers of reticulocytes were low during P vivax malaria infection and increased following clearance of parasites from the peripheral blood.5 Others have made similar observations in P falciparum, but have not systematically studied suppression of erythropoiesis in relation to the degree of anemia. We have shown that the degree of inadequate reticulocyte response was greater in anemic children (Figure 3) and that the proportion of normal erythroid precursors in the bone marrow was associated with hematocrit on admission.

A study of malarial anemia in Kenyan children found high plasma concentrations of Epo and soluble transferrin receptor (sTFR) and suggested that erythropoiesis is adequate in mild malaria infection.33 Most previous studies have shown that Epo was appropriately raised in children from endemic areas and in nonimmune adults presenting with malaria and mild anemia.7,34-36 We also found raised concentrations of Epo in children with malarial anemia. However, given the low reticulocyte response in the presence of gross anemia and the marked dyserythropoiesis present in the bone marrow, our interpretation of the data is that erythropoietin levels do not predict the erythropoietic response in malaria.

The cause(s) of abnormal erythropoiesis in falciparum malaria has been uncertain. Published data detailing the bone marrow histology and function in bone marrow samples from children with malaria show profound dyserythropoiesis (Figure 5; Newton et al7 ; and Abdalla et al8 ) and abnormal cell cycle kinetics.37 High levels of TNF-α may suppress BFU-e's directly through the expression of TNF p55 and p75 receptors38 and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand,39 or they may suppress BFU-e's indirectly through accessory cells.40 The severity of the morphologic features of dyserythropoiesis suggests, however, that factors other than proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to inadequate erythropoiesis during malaria infection.

Our data show that Hz may directly suppress erythropoiesis in vitro. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing a direct effect of Hz on erythroid development. Malarial pigment was first characterized biochemically as hemozoin over a century ago by Carbone41 and has more recently been described to impair the function of human endothelial cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells in vitro.22,42,43

Hz is intensely biologically active and catalyzes the formation of free radicals through repeated redox cycles initiated by the Fe (III) moiety.19 The effect of Hz may be reproduced by equivalent amounts of synthetic α and β hematin, and it seems likely that intracellular or membrane-bound Hz in contact with erythroid cells causes cellular dysfunction and oxidative damage (Abigail Lamikanra, Taco Kooij, and David Roberts, manuscript submitted).

The findings of our clinical study are consistent with independent effects of Hz and TNF-α on erythropoiesis. Following initial observations of an association between intraleukocytic Hz and outcome,44,45 other studies have reported univariate associations of HCMs and plasma TNF-α with anemia17 and HCMs and severe anemia.46 Our study shows a significant association between the proportion of HCMs and anemia and also HCMs and plasma Hz with suppression of the reticulocyte response after adjusting for TNF-α and IFN-γ concentration.

A direct effect of Hz on erythropoiesis could explain the relationship between IL-10 and protection from anemia shown here and previously reported by others.36,47,48 We suggest that IL-10 may ameliorate the effects of heme at least in part through the induction of hemeoxygenase-1, which converts heme into CO, Fe2+, and biliverdin.49

The proportion of monocytes that contain Hz probably reflects the total amount of Hz produced during infection, and may also reflect the degree of deposition of Hz in the bone marrow, stromal cells, and hematopoietic cells. To assess the direct effects of Hz on hematopoietic cells, we have measured circulating Hz in plasma, and directly observed Hz within erythroid and myeloid precursors in the bone marrow.

To our knowledge, plasma Hz has not been measured before in clinical samples from children with malaria. We found that Hz circulated in plasma at a concentration found to be inhibitory in our in vitro studies (1-10 μg/mL). Plasma Hz was significantly associated with anemia and with reticulocyte suppression and not with plasma cytokine concentrations.

The bone marrow sections from children who died with severe malaria show gross dyserythropoiesis. In these sections, we found a significant association between the quantity of Hz (located in erythroid precursors and myeloid cells—mainly macrophages) and the proportion of erythroid cells that was abnormal. These findings are consistent with a direct inhibitory effect of Hz on erythropoiesis.

We have considered whether our findings could be confounded by other causes of altered reticulocyte production and/or abnormal erythropoiesis. We could not assess iron status directly, and the indirect markers of iron status, such as ferritin and microcytosis, are unreliable in acute malaria infection or in populations with high levels of α-thalassemia trait as in Kenya. A descriptive survey of the causes of severe anemia in this population showed that iron deficiency was present in 17% of children with severe anemia.7 The standard practice is, therefore, to treat all anemic children with ferrous sulfate in addition to antimalarial drugs. We believe the response of some children to iron would not affect the conclusion of this study, as exclusion of those children with low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) (< 65 fL) from the analysis strengthened the association of anemia and Hz (data not shown).

Our data do not preclude an indirect effect of Hz on erythropoiesis in vivo. Hz-containing macrophages are plentiful in bone marrow specimens taken during acute malaria infection (Knuettgen50 ; Table 5). Hz may stimulate the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by monocytes or produce endoperoxides, such as 15(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic (HETE) and hydroxy-nonenal (HNE), through oxidation of membrane lipids.51-53 Endoperoxides produced in HCMs may impair erythroid growth.54 However, in this model system, there is little, if any, loss of biologic activity after delipidation of Hz, the number of CD14+ myeloid cells is low, and TNF-α was undetectable (< 32 pg/mL) in the culture supernatants. We have demonstrated that Hz and TNF-α show not only independent, but also additive, inhibitory effects on erythroid growth and development in vitro.

Similarly, we cannot exclude the possibility that other parasite or host factors are at least partly responsible for ineffective erythropoiesis. The glycosylphosphadityl inositol (GPI) anchor from P falciparum can modulate cytokine secretion and responses in macrophages and endothelial cells in vitro, but has not been shown to be directly or indirectly inhibitory for erythropoiesis.55 Similarly, macrophage-inhibitory factor (MIF) has been shown to contribute to the pathophysiology of bone marrow failure in rodent models of malaria.56 We were unable to study the role of MIF in malarial anemia in this study, but further investigation of the role of MIF in anemia would be of interest. Although there are diverse mechanisms that might contribute to the pathogenesis of malarial anemia, both our experimental and clinical data are consistent with a direct effect of Hz on erythroid precursors.

Given the broad biologic effects of Hz, it is possible that Hz may also contribute to anemia by mechanisms other than inhibition of erythropoiesis, for example decreased red cell deformability.57,58

Anemia is always the result of a profound disturbance of the finely tuned balance between erythrocyte production and loss. This study underlines the importance of ineffective erythropoiesis in the pathophysiology of malarial anemia in African children. The results of this study are consistent with the hypothesis that malarial pigment may directly or indirectly suppress erythropoiesis. A role for Hz in the pathology of SMA may have implications for the prevention and treatment of severe malarial anemia.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 27, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2006-05-018697.

Supported by the University of Oxford and a Beca de Formación en Investigación (BEFI) grant (Instituto de Salud Carlos III [ISCIII], Ministry of Health, Spain) (C.C.-P.); by the National Blood Service (NBS), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the European Union (EU) Biology and Pathology of Malaria Parasite Network of Excellence (BioMalPar) NoE (D.J.R.); and by the National Health Service (NHS) Research and Development (R&D) Directorate, Wellcome Trust, EU, and the Medical Research Council (MRC) (J.O.P.C. and S.M.W.). The research was carried out in part at the NBS-Oxford Centre and benefits from NHS R&D funding. The Centre for Geographic Medicine-Coast is supported by core funds from the Wellcome Trust, UK, and the Kenyan Institute of Medical Research. M.E.M. and the Malawi Programme are supported by the Wellcome Trust.

C.C.-P. contributed to the experimental studies, study design, protocols, preparation and examination of samples, collection of clinical data, and analysis of data and preparation of the paper; O.K. and M.N. contributed to the optimization of protocols and preparation and examination of clinical samples; M.M. established the postmortem study in Malawi, provided samples for analysis, and edited the paper; S.W. counted histopathology slides; B.L. assisted in the preparation of laboratory protocols and supervised the laboratory work in Kenya; N.P., C.R.J.C.N., K.M., and T.N.W. contributed to the study design, supervision of recruitment and clinical work, and the editing of the paper; J.O.P.C. and S.M.W. contributed to study design and data analysis for in vitro erythropoiesis studies and to editing the paper; and D.J.R. contributed to the initiation of the project, experimental study design and protocols, data analysis, and preparation of the paper.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank the clinical and technical staff, especially Maimuna Ahmed in Kilifi, for their skilled and careful help. We thank Profs D. Weatherall, P. Arese, and K. Marsh as well as Drs W. Wood, P. Bull, B. Elford, and A. Lamikanra for comments, encouragement, and advice. Prof P. Arese and Dr E. Schwarzer generously gave essential advice regarding measurement of plasma hemozoin.

![Figure 3. Difference in the reticulocyte counts before and after treatment in children with acute malarial anemia. The mean absolute reticulocyte counts (× 109/L) on admission and one week after treatment in children with severe anemia (Hb, < 50 g/L [5 g/dL]), moderate anemia (Hb, 50-69 g/L [5-6.9 g/dL]), mild anemia (Hb, 70-100 g/L [7-10 g/dL]), and no anemia (Hb, > 100 g/L [10 g/dL]). The bars show the mean values; error bars, 95% CI.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/108/8/10.1182_blood-2006-05-018697/4/m_zh80200602540003.jpeg?Expires=1765893512&Signature=reMimnsWpe2kqp1on~d43pD4UZFKYb~2Z9XB1MzdOz9bgsD0Iz3erVk7sA6BnRCI0IIONskuo1eQl0G3VQXth8-Z6t4jt~h9fY0akeCNLw80iWtZq3NFUi4u3~~YFmeV5rii5Fc8KpMwfW7EG84vaJUO90f1r0bEuCjhdRHTEtJxG~OrbVqV6qOxAgHzgpyh9~PkN8zIzkbjKBr~akdJF6wPwJbWJGhEwrs28KgPaWJR7j01~MPyiiK-emvft65dxypgigy9WNfH3TPZ0ueYnDZ5vprszI-Md4oU-oSo0t1C6LDNeF6WEUTm987RvDEhlETXsyqpB1jbmTaf6oMlkA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal