Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells were recently shown to play a relevant role in the process of dendritic cell (DC) maturation. This function is exerted either by direct DC stimulation or through killing those DCs that did not properly acquire a mature phenotype. While killing of immature DCs is dependent on the function of the NKp30 triggering receptor, the mechanism by which NK cells induce DC maturation is still unclear. In this study, we show that also the NK-mediated induction of DC maturation is dependent on NKp30. Upon NK/DC interaction, resulting in NKp30 engagement, NK cells produced tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (and interferon γ [IFNγ]) that, in turn, promoted DC maturation. Masking of NKp30 with specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) strongly reduced maturation of DCs cocultured with NK cells. In addition, supernatant from NK cells stimulated via NKp30 induced DC maturation, and this effect was neutralized by anti-TNFα antibodies (Abs). This NKp30 function is controlled by the HLA-specific inhibitory NK receptors. Accordingly, the ability to promote maturation was essentially confined to NK cells expressing the killer immunoglobulin-like receptor–negative (KIR–) NKG2Adull phenotype. Finally, the analysis of perforin-deficient NK cells allowed the dissection of the 2 NKp30-mediated NK-cell functions, since NKp30 could induce cytokine-dependent DC maturation in the absence of NK-mediated DC killing.

Introduction

One of the hallmarks of natural killer (NK) cells is their ability to kill tumors or virus-infected cells.1 This implies that, during immune responses, NK cells would be involved mainly in the direct attack and clearance of these particular threats. In the past, this function has been largely documented both in mice and in humans.1-7 On the other hand, recent studies have provided evidence that, besides their effector functions, NK cells may also play a role in the regulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses.8-12 In this context, NK cells can first interact with dendritic cells (DCs) in inflamed peripheral tissues. Subsequently, NK cells and DCs may further interact in secondary lymphoid compartments such as lymph nodes that are populated by a specialized NK-cell subset characterized by the CD56++, CD16–, CD94/NKG2A+ (natural killer group protein 2-A) surface phenotype.12-15 These NK cells are poorly represented in peripheral blood and are characterized by low cytolytic activity while they release abundant interferon γ (IFNγ).16 During the first encounter in peripheral tissues, the bidirectional cross talk between NK cells and DCs has been proposed to play a relevant role in the mechanisms leading to selection of DCs with maximal capability of priming T helper 1 (Th1) responses.11,17 Among the functional events that are thought to play a role in shaping DCs during NK-DC interaction, a prominent role has been assigned to interleukin 12 (IL12), released by DCs undergoing maturation after antigen (Ag) uptake. In particular, upon engagement of their Toll-like receptors (TLRs)18 by microbial products, DCs secrete IL12 that, in turn, promotes both increments of NK-cell cytotoxicity and IFNγ release.19,20 This phenomenon is particularly evident when both DCs and NK cells are stimulated by microbial products acting on their TLRs. For example, upon engagement of TLR3 by poly:IC, NK cells undergo activation and, in the presence of IL12, acquire the ability to kill immature DCs (iDCs) but not mature DCs (mDCs).19 The NK-cell subset that mediates killing of autologous iDCs has been identified recently with a cell population expressing the CD56+ CD16+ NKG2A+ killer immunoglobulin-like receptor–negative (KIR–) NKp30+ surface phenotype.21 A major role in the NK-mediated lysis of DCs is played by the NKp30 triggering receptor.8,22

Besides their cytolytic activity, NK cells are also high producers of cytokines such as IFNγ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα).1 Accordingly, a role for NK cells has been proposed both in the enhancement of inflammatory responses in peripheral tissues and in shaping (adaptive) T-cell responses in lymph nodes.11,12,15,23 In this context, recent studies revealed that the CD56brightCD16– NK cells proliferate and produce cytokines upon interaction with iDCs.23 In turn, activated NK cells have been shown to induce DC maturation.

While the molecular interactions occurring in the NK-cell–mediated DC killing have been, at least in part, elucidated, those regulating the NK/DC cross talk resulting in DC maturation are still undefined.

The present study was designed to analyze the molecular basis of this phenomenon.

Materials and methods

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

The following mAbs, produced in our lab, were used in this study: JT3A (immunoglobulin G2a [IgG2a], anti-CD3), c127 (IgG1, anti-CD16), F252 and AZ20 (IgM and IgG1, respectively, anti-NKp30), KL247 (IgM, anti-NKp46), KS38 (IgM, anti-NKp44), BAT221 (IgG1, anti-NKG2D), A6/220 (IgM, anti-CD56), EB6b (IgG1, anti-KIR2DL1 and -KIR2DS1), GL183 (IgG1, anti-KIR2DL2,- KIR2DL3, and -KIR2DS2), FES172 (IgG2a, anti-KIR2DS4), Z27 (IgG1, anti-KIR3DL1), XA185 (IgG1, anti-CD94), Z199 (IgG2b, anti-NKG2A), and A6-136 (IgM, anti–HLA class I). Anti-CD1a (IgG1–phycoerythrin [PE]), anti-CD14 (IgG2a), anti-CD83 (IgG2b), and anti-CD86 (IgG2b-PE) were purchased by Immunotech (Marseille, France); delta G9 (IgG2b anti–human perforin; Ancell, Bayport, MN), anti-TNFα rabbit antisera (Peprotech, London, United Kingdom), and anti-IFNγ mAb (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were commercially available.

D1.12 (IgG2a, anti–HLA-DR) mAb was provided by Dr R. S. Accolla (Pavia, Italy). HP2.6 (IgG2a, anti-CD4) mAb was provided by Dr P. Sanchez-Madrid (Madrid, Spain).

Generation of polyclonal or clonal NK-cell populations

In order to obtain peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated on Ficoll-Hypaque gradients and depleted of plastic-adherent cells. Purified NK cells were isolated by incubating PBLs with anti-CD3 (JT3A), anti-CD4 (HP2.6), and anti–HLA-DR (D1.12) mAbs (30 minutes at 4°C) followed by goat-antimouse coated Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) (30 minutes at 4°C) and immunomagnetic depletion. CD3–4–DR– cells were cultured on irradiated feeder cells in the presence of 100 U/mL recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2, Proleukin; Chiron, Emeryville, CA) and 5 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) in order to obtain polyclonal NK-cell populations, or after limiting dilution NK-cell clones. The NK-cell populations were assessed for purity, and only those homogeneously displaying CD3–CD56+NKp30+NKp46+ phenotype of classical NK cells were selected and used for inducing DC maturation.

NK cells were derived from either healthy donors or from a hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) patient who has been previously described (patient no. 1 in Aricò etal24 )

Approval was obtained from the University of Genoa (Italy) review board. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Generation of DCs

Dendritic cells (DCs) were generated as follows: PBMCs were derived from healthy donors and were seeded in 25-mm2 plastic flasks at a density of 5 × 106 cells/mL. After 30 minutes at 37°C, nonadherent cells were removed. To obtain a nearly pure adherent cell population, extensive repeated washes were performed. Plastic adherent cells were then cultured in the presence of IL-4 and GM-CSF (Peprotech) at the final concentration of 20 ng/mL and 50 ng/mL, respectively. After 6 days of culture, DC purity was assessed by cytofluorometric analysis. Cells displaying high forward scatter (FSC)–side scatter (SSC) values ranged from 80% to 95% and were all CD14–CD1a+CD83– iDCs. The remaining 5% to 20% FSClowSSClow cells were essentially represented by CD19+CD20+ B lymphocytes. Only purified cell populations containing 90% or more of cells displaying classical iDC phenotype were selected for coculture experiments. The possible interference of contaminating lymphocytes was ruled out in control experiments in which comparable levels of DC maturation were obtained before and after immunomagnetic depletion of residual lymphocytes. In order to generate CD14–, CD1a+, CD83+, CD86+ mature DCs (mDCs), iDCs were stimulated for 2 days with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at the final concentration of 1 μg/mL.

Induction of DC maturation

iDCs were plated in 96-well round-bottomed microtiter plate at 5 × 104 cells/well either in the absence or in the presence of the NK-cell lines or clones (DC/NK ratio: 5:1). Unless specifically mentioned, myeloid DCs were cultured with allogeneic NK cells. In some experiments, iDCs were given 100 μL culture supernatant from either unstimulated or NKp30-stimulated NK cells. After 2 days, DCs were harvested and were assessed for the expression of the maturation markers CD83 and CD86. As control, optimal DC maturation was induced by the addition of LPS at the final concentration of 1 μg/mL. Where described, anti-NK receptor mAbs or anti-CD56 control mAb were added at the onset of the experiments at the final concentration of 5 μg/mL. In the experiments of cytokine neutralization, saturating amounts of anticytokine antibodies were either added at the onset of the NK/DC cocultures or mixed with supernatants from stimulated NK cells and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C.

NK-cell stimulation and cytokine analysis

NK-cell lines and clones were stimulated as follows. NK cells (5 × 105) were cultured overnight in a plastic well (1 mL/well) precoated or not with anti-NKp30 mAb (F252 IgM 5 μg/mL) or anti-CD56 control mAb (A6/220 IgM 5 μg/mL). The culture supernatants were then collected, analyzed for the presence of TNFα and IFNγ, and used to stimulate DC maturation as described in “Induction of DC maturation.” Cytokine analysis was carried out using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from Bio-Source International (Camarillo, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytofluorometric analysis and cytolytic activity

For cytofluorometric analysis (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA), cells were stained with the appropriate labeled or unlabeled mAb. In the case of unlabeled mAbs, staining was followed by PE- or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated isotype-specific goat anti-mouse second reagent (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). For the assessment of perforin expression, NK cells were incubated in Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (Pharmingen–Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) for 20 minutes at 4°C and washed twice in Perm/Wash solution supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and then stained with the appropriate antiperforin antibody. Polyclonal NK-cell populations derived from either control donor or the HLH patients were tested for cytolytic activity in a 4-hour 51Cr-release assay against either the P815 FcγR+ murine cell line or allogeneic iDCs. The concentration of the various mAbs added in the assays was 10 μg/mL in the masking experiments and 1 μg/mL in the redirected killing experiments. The effector-target (E/T) ratios are indicated in the text.

Results and discussion

NKp30 is involved in the induction of DC maturation by NK cells

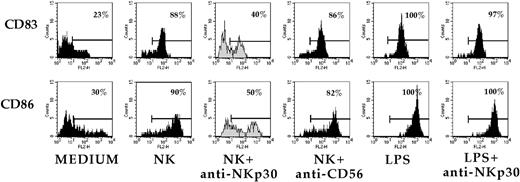

Previous studies suggested that NK cells induce DC maturation only in the presence of direct cell-to-cell contact.9,10 This would imply that surface receptor/ligand interactions are, at least in part, responsible for this phenomenon. In this context, NKp30 has recently been shown to play a crucial role in NK/DC interactions.8 While it is now well established that the engagement of NKp30 (by still undefined ligand[s]) triggers the NK-mediated killing of iDCs, it is still unclear whether NKp30 is also involved in the induction of DC maturation. In order to explore this possibility, iDCs were cocultured with a polyclonal NK-cell line either in the absence or in the presence of a different mAb to one or another triggering NK receptor. When available, we used mAbs of IgM isotype in order to efficiently block the receptor/ligand interaction and to avoid nonspecific effects due to binding to Fcγ receptors (expressed on both cell types). As shown in Figure 1, DCs that had been cultured for 2 days with NK cells acquired a surface phenotype typical of mature DCs. Indeed, the expression of CD83, CD86 (Figure 1), HLA class I, and HLA class II molecules (not shown) was up-regulated. However this phenomenon was strongly inhibited by anti-NKp30 mAb (F252 IgM). The effect was specific since (a) the addition of a control anti-CD56 mAb (A6/220 of IgM isotype) did not inhibit DC maturation; and (b) anti-NKp30 mAb selectively inhibited the NK-dependent DC maturation, while it was ineffective when DC maturation was induced by other stimuli such as LPS (Figure 1). Blocking of other triggering NK receptors had little (NKp46) or no (NKp44, h2B4, NKG2D) effect on DC maturation (not shown).

Induction of DC maturation by NK cells involves NKp30 receptor engagement. Immature DCs were cocultured with an allogeneic polyclonal NK-cell line for 2 days in the absence or in the presence of anti-NKp30 mAb or anti-CD56 mAb (both of IgM isotype). Controls included iDCs cultured either in medium alone or in the presence of LPS (1 μg/mL) or in the presence of both LPS and anti-NKp30 mAb. DCs were then analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence and cytofluorometric analysis for expression of CD83 and CD86. The percent of positive cells is indicated. Horizontal bars represent markers assigned on the basis of control cells fluorescence intensity (ie, cells incubated with the second reagent alone). Results are representative of 6 independent experiments.

Induction of DC maturation by NK cells involves NKp30 receptor engagement. Immature DCs were cocultured with an allogeneic polyclonal NK-cell line for 2 days in the absence or in the presence of anti-NKp30 mAb or anti-CD56 mAb (both of IgM isotype). Controls included iDCs cultured either in medium alone or in the presence of LPS (1 μg/mL) or in the presence of both LPS and anti-NKp30 mAb. DCs were then analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence and cytofluorometric analysis for expression of CD83 and CD86. The percent of positive cells is indicated. Horizontal bars represent markers assigned on the basis of control cells fluorescence intensity (ie, cells incubated with the second reagent alone). Results are representative of 6 independent experiments.

Engagement of NKp30 induces NK cells to release TNFα (and IFNγ), which promotes DC maturation

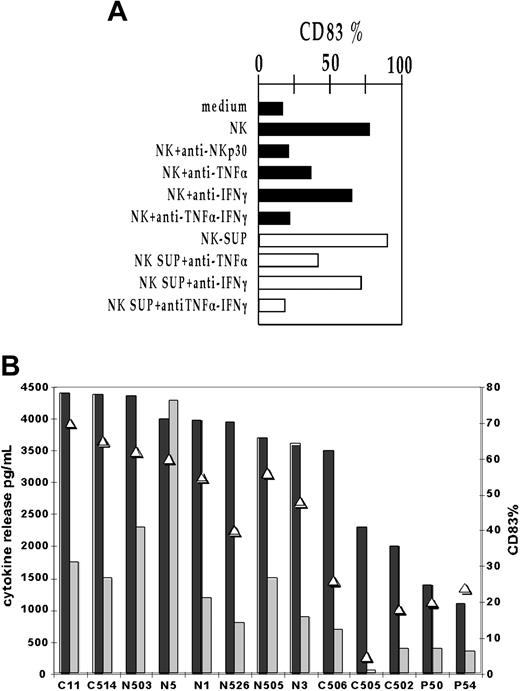

The results shown in Figure 1 suggest that the engagement of NKp30 in NK cells is essential to promote DC maturation, but does not explain how this event may actually occur. Previous reports suggested that secretion of cytokines, such as TNFα and, to a minor extent, IFNγ, may complement the maturing stimuli mediated by direct NK/DC cell contact.9,10 To directly assess this possibility, we used neutralizing anti-TNFα (or anti-IFNγ) mAbs. As shown in Figure 2A, anti-TNFα strongly inhibited the NK-mediated DC maturation (as assessed by the up-regulation of CD83 surface density), while anti-IFNγ antibodies had only a marginal effect. Maximal inhibition, however, could be detected only upon neutralization of both cytokines. Remarkably, mAb-mediated blocking of NKp30 or cytokine neutralization had comparable effects, since they resulted in an almost complete inhibition of DC maturation (Figure 2A). This suggests that during the NK/DC interaction, the engagement of NKp30 and the cytokine production by NK cells may represent different steps of the same event. Indeed culture supernatants obtained by stimulating the same NK cells with plastic-bound anti-NKp30 mAb induced levels of DC maturation comparable with those detectable when iDCs were cultured with (unstimulated) NK cells (Figure 2A). Moreover this effect was strongly inhibited when supernatants were pretreated with anti-TNFα or anti-TNFα+ anti-IFNγ neutralizing antibodies.

Analysis of NK-mediated DC maturation at the clonal level

The experiments analyzed in Figure 2 indicate that, upon DC/NK interaction, the engagement of NKp30 triggers NK cells to produce cytokines (particularly TNFα) promoting DC maturation. This was further confirmed by the analysis of a large panel of NK clones derived from different healthy donors. In this experiment, a large number of NK clones were stimulated by plastic-bound anti-NKp30 mAb, and their supernatants were assessed for the ability to induce DC maturation and for the presence of TNFα and IFNγ.As shown in Figure 2B, in each supernatant, a direct correlation could be established between the concentration of TNFα and the ability to induce DC maturation. No correlation was found with the production of IFNγ, thus confirming that this cytokine plays only an accessory role in the induction of DC maturation. Among the various clone-derived supernatants analyzed, only one failed to promote DC maturation (clone C505 in Figure 2B). This clone, besides its production of small amounts of TNFα, did not release any IFNγ in response to anti-NKp30 mAb. This suggests that the contribution of IFNγ to DC maturation may be relevant only in the case of suboptimal concentrations of TNFα.

Role of TNFα and IFNγ in the induction of DC maturation by NK cells. (A) DCs were cultured for 2 days in the presence of different stimuli and then analyzed for expression of CD83. ▪ indicates iDCs that were cultured alone or cocultured with an allogeneic polyclonal NK-cell line either in the absence or in the presence of the indicated Abs. □ indicates iDCs that were cultured in the presence of supernatant derived from NK cells stimulated by plastic-bound anti-NKp30 mAb (NK SUP). Where indicated, supernatants were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with anti-TNFα, anti-IFNγ, or a mixture of both antibodies before culture with iDCs. Results are representative of 6 independent experiments. (B) A series of NK clones were stimulated with plastic-bound anti-NKp30 mAb (IgM isotype) overnight. Supernatants were then harvested and analyzed for TNFα (▪) and IFNγ (▦) content by specific ELISA. The same supernatants were also tested for their capability to induce DC maturation in a 2-day culture with immature DCs. ▵ indicates the percent of CD83+ DCs after the culture with each NK clone–derived supernatant.

Role of TNFα and IFNγ in the induction of DC maturation by NK cells. (A) DCs were cultured for 2 days in the presence of different stimuli and then analyzed for expression of CD83. ▪ indicates iDCs that were cultured alone or cocultured with an allogeneic polyclonal NK-cell line either in the absence or in the presence of the indicated Abs. □ indicates iDCs that were cultured in the presence of supernatant derived from NK cells stimulated by plastic-bound anti-NKp30 mAb (NK SUP). Where indicated, supernatants were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with anti-TNFα, anti-IFNγ, or a mixture of both antibodies before culture with iDCs. Results are representative of 6 independent experiments. (B) A series of NK clones were stimulated with plastic-bound anti-NKp30 mAb (IgM isotype) overnight. Supernatants were then harvested and analyzed for TNFα (▪) and IFNγ (▦) content by specific ELISA. The same supernatants were also tested for their capability to induce DC maturation in a 2-day culture with immature DCs. ▵ indicates the percent of CD83+ DCs after the culture with each NK clone–derived supernatant.

NK-mediated DC maturation is influenced by HLA class I–specific inhibitory receptors

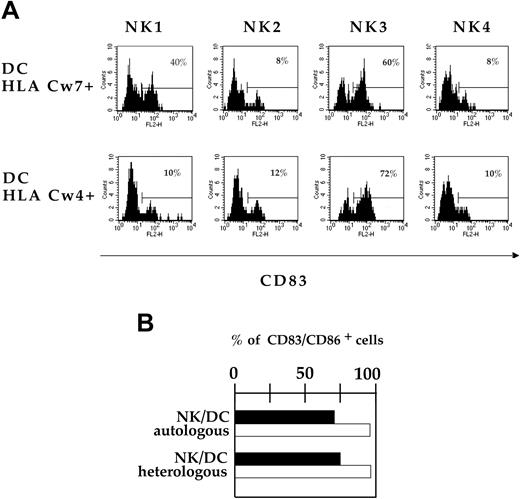

In this set of experiments, we analyzed whether engagement of inhibitory KIRs25 or NKG2A25 can modulate the ability of NK cells to induce DC maturation. To this end, iDCs derived from different donors were cocultured with selected NK-cell clones whose inhibitory receptors did or did not recognize HLA class I alleles expressed by DCs. Maturation of DCs cocultured with NK-cell clones was then evaluated by the analysis of CD83 surface expression.

As shown in Figure 3, a representative NK-cell clone (NK1) expressing the KIR2DL1+ KIR2DL2/3– KIR3DL– NKG2A– phenotype induced little CD83 surface expression in DCs that were homozygous for HLA-Cw4 alleles (recognized by the KIR2DL1 receptor25 ). On the other hand, the same NK clone could induce efficient maturation of DCs homozygous for HLA-Cw7 alleles (not recognized by the KIR2DL1 receptor25 ). NK clones coexpressing KIR2DL1 (specific for the HLA-Cw4) and KIR2DL2/3 (specific for HLA-Cw7) induced poor maturation on both DC types (see the representative clone NK2 in Figure 3). Thus, the engagement of KIRs appears to weaken the ability of NK cells to induce DC maturation.

We next assessed whether the same regulatory effect could also be mediated by the HLA-E–specific NKG2A inhibitory receptor. NKG2Abright and NKG2Adull NK-cell clones can be identified on the basis of the staining intensity with specific anti-NKG2A mAbs.21 As shown in Figure 3, a representative KIR– NKG2Adull NK-cell clone (NK3) efficiently induced maturation of both DCs analyzed, whereas a KIR– NKG2Abright clone (NK4) did not. This result is in line with previous data regarding the ability of NK clones to kill immature DCs. Indeed only NKG2Abright NK clones could “sense” the low levels of HLA-E expression, a typical feature of immature DCs.21

Role of HLA class I–specific inhibitory receptors in the regulation of NK-induced DC maturation and analysis of NK-cell–induced DC maturation in an autologous versus heterologous setting. (A) Immature DCs expressing either the HLA class I Cw7+/+ or the HLA class I Cw4+/+ phenotype were cocultured in the presence of allogeneic NK clones expressing different KIR phenotypes. After 2 days of coculture, DCs were analyzed for expression of CD83. The reported data of DC maturation were obtained in the presence of the following 4 representative NK clones: NK1 expressing the KIR2DL1+ KIR2DL2/3– NKG2A– phenotype, NK2 expressing the KIR2DL2/3+ KIR2DL1+ NKG2A– phenotype, and NK3 and NK4 characterized by the KIR-negative NKG2Adull and NKG2Abright phenotype, respectively. Horizontal bars represent markers assigned on the basis of control cells (ie, cells incubated with the second reagent alone). The percentage of CD83+ cells is indicated. (B) A polyclonal NK-cell line was cocultured in the presence of either autologous or heterologous DCs. After 2 days of coculture, DCs were analyzed for expression of CD83 and CD86. Black bars and white bars indicate the percent of CD83+ DCs and CD86+ DCs, respectively. Similar results were obtained using NK-cell lines derived from 4 additional donors.

Role of HLA class I–specific inhibitory receptors in the regulation of NK-induced DC maturation and analysis of NK-cell–induced DC maturation in an autologous versus heterologous setting. (A) Immature DCs expressing either the HLA class I Cw7+/+ or the HLA class I Cw4+/+ phenotype were cocultured in the presence of allogeneic NK clones expressing different KIR phenotypes. After 2 days of coculture, DCs were analyzed for expression of CD83. The reported data of DC maturation were obtained in the presence of the following 4 representative NK clones: NK1 expressing the KIR2DL1+ KIR2DL2/3– NKG2A– phenotype, NK2 expressing the KIR2DL2/3+ KIR2DL1+ NKG2A– phenotype, and NK3 and NK4 characterized by the KIR-negative NKG2Adull and NKG2Abright phenotype, respectively. Horizontal bars represent markers assigned on the basis of control cells (ie, cells incubated with the second reagent alone). The percentage of CD83+ cells is indicated. (B) A polyclonal NK-cell line was cocultured in the presence of either autologous or heterologous DCs. After 2 days of coculture, DCs were analyzed for expression of CD83 and CD86. Black bars and white bars indicate the percent of CD83+ DCs and CD86+ DCs, respectively. Similar results were obtained using NK-cell lines derived from 4 additional donors.

A further indication that NK-induced DC maturation is controlled by HLA-specific inhibitory receptors is provided by the observation that, following masking of HLA class I molecules by appropriate specific mAbs (A6/136 IgM), DC maturation could be induced also by “KIR-matched” or NKG2Abright NK clones (NK2 and NK4 clones, respectively) (not shown).

These data indicate that the NK-driven DC maturation results from a balance between positive signals, mediated by NKp30, and negative ones, delivered by inhibitory HLA class I–specific receptors. In this context, one may ask whether the process of DC maturation driven by NK cells may normally occur “in vivo” (where NK cells are in contact with autologous HLA class I molecules) or, rather, it may become relevant only in those peculiar conditions (such as transplants) in which heterologous interactions would take place. In order to answer this question, the ability of a polyclonal NK-cell line to induce DC maturation was compared in a heterologous versus an autologous setting. As shown in Figure 3B, NK cells were able to induce maturation of both heterologous and autologous DCs (as detected by the expression of the CD83 and CD86 markers). Moreover, no significant differences in terms of CD83+/CD86+ DCs could be detected between the 2 different NK/DC combinations.

Thus, maturation of myeloid DCs appears to be efficiently promoted also in an autologous setting. This can be explained by the fact that the major NK-cell population promoting the maturation of DCs is represented by KIR–NKG2Adull NK cells. Importantly, these cells can induce DC maturation independently of the HLA haplotype of the donor analyzed. Although in certain heterologous settings, an increment in terms of DC maturation might be expected as a consequence of KIR mismatch between NK and DCs, the actual detection of this phenomenon may be impaired by the relatively low number of alloreactive (KIR mismatched) cells.26

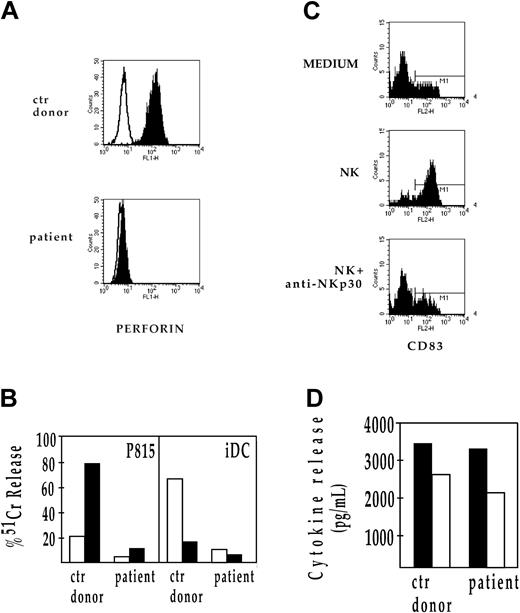

Analysis of DC maturation induced by perforin-deficient NK cells from a patient with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

Since NK cells use the same triggering receptor (NKp30) for both cytokine release and killing, it might be difficult to establish the relative contribution of these 2 functional activities to the promotion of DC maturation. Indeed, while NK-mediated killing of iDCs would simply result in enrichment of mDCs, the release of relevant cytokines would complement cytotoxicity by directly promoting DC maturation, a process that renders DCs resistant to NK-mediated killing. Along this line, recent data10 suggest that, while DC killing would occur preferentially when NK cells are numerically preponderant (eg, NK/DC ratio: 5:1), DC maturation would take place when the number of DCs exceeds that of NK cells (eg, NK/DC ratio: 1:5). In the experimental conditions used in our study (NK/DC ratio: 1:5), NK cells promoted DC maturation without inducing significant DC killing. Indeed, the various NK/DC pairs in the coculture experiments were also analyzed in a 51Cr release cytolytic assay. At the 1:5 E/T ratio, the NK-mediated DC killing never exceeded 5% lysis (not shown). The dissection of the 2 major functional outcomes induced by the engagement of NKp30, however, was obtained by the use of noncytolytic NK cells (Figure 4). In these experiments, we derived a polyclonal NK-cell line and some NK-cell clones from an HLH patient24 characterized by a profound defect in the expression of perforin. These cells were first assessed by cytofluorometric analysis, for the expression of intracytoplasmic perforin. As shown in Figure 4A, perforin was indeed virtually absent in NK cells from the HLH patient, while it was expressed at high levels in NK cells from a healthy donor. On the other hand HLH-NK cells were equipped with a normal set of the major triggering receptors (including natural cytotoxicity receptor [NCR] and NKG2D) (not shown). HLH-NK cells were analyzed by redirected killing against the FcγR+ P815 cell line, either in the absence or in the presence of anti-NKp30 mAb (AZ20 IgG1). In contrast to the control, they did not display spontaneous or anti-NKp30–induced killing of P815 target cells (Figure 4B). Although not shown, no increments of cytolytic activity could be detected by the use of mAbs specific for other triggering receptors (including NKp46, NKp44, and NKG2D).

Analysis of DC maturation induced by perforin-deficient NK cells. (A) Polyclonal NK-cell lines derived from either a healthy donor or an HLH patient were assessed for intracytoplasmic expression of perforin (“Materials and methods”). Open curves indicate isotypic controls, while filled curves indicate perforin expression in the HLH patient and in a healthy donor, in the lower and upper panels, respectively. (B, left) The same polyclonal NK-cell lines were analyzed for their cytolytic responses in a redirected killing assay against the FcγR+ target cell, P815. Specific 51Cr release was assessed either in the absence (□) or in the presence (▪) of a triggering anti-NKp30 mAb (IgG1 isotype). E/T ratio was 4:1. (Right) Cytolytic activity was also evaluated against allogeneic iDCs, either in the absence (□) or presence (▪) of anti-NKp30mAb (IgM isotype). E/T ratio was 8:1. (C) Immature DCs were cocultured with a polyclonal NK-cell line derived from a perforin-deficient HLH patient either in the absence or presence of anti-NKp30 mAb (IgM isotype). As control, iDCs were cultured with medium alone. After 2 days, DCs were harvested and analyzed for expression of CD83. Results are presented as percent of positive cells and are representative of 6 independent experiments. Horizontal bars represent markers assigned on the basis of control cells fluorescence intensity (ie, cells incubated with the second reagent alone). (D) NK cells from a healthy donor or from a perforin-deficient patient were stimulated overnight by plastic-bound anti-NKp30. Supernatants were harvested and analyzed by specific ELISA for their TNFα and IFNγ content. ▪represents TNFα release, while □ represents IFNγ release.

Analysis of DC maturation induced by perforin-deficient NK cells. (A) Polyclonal NK-cell lines derived from either a healthy donor or an HLH patient were assessed for intracytoplasmic expression of perforin (“Materials and methods”). Open curves indicate isotypic controls, while filled curves indicate perforin expression in the HLH patient and in a healthy donor, in the lower and upper panels, respectively. (B, left) The same polyclonal NK-cell lines were analyzed for their cytolytic responses in a redirected killing assay against the FcγR+ target cell, P815. Specific 51Cr release was assessed either in the absence (□) or in the presence (▪) of a triggering anti-NKp30 mAb (IgG1 isotype). E/T ratio was 4:1. (Right) Cytolytic activity was also evaluated against allogeneic iDCs, either in the absence (□) or presence (▪) of anti-NKp30mAb (IgM isotype). E/T ratio was 8:1. (C) Immature DCs were cocultured with a polyclonal NK-cell line derived from a perforin-deficient HLH patient either in the absence or presence of anti-NKp30 mAb (IgM isotype). As control, iDCs were cultured with medium alone. After 2 days, DCs were harvested and analyzed for expression of CD83. Results are presented as percent of positive cells and are representative of 6 independent experiments. Horizontal bars represent markers assigned on the basis of control cells fluorescence intensity (ie, cells incubated with the second reagent alone). (D) NK cells from a healthy donor or from a perforin-deficient patient were stimulated overnight by plastic-bound anti-NKp30. Supernatants were harvested and analyzed by specific ELISA for their TNFα and IFNγ content. ▪represents TNFα release, while □ represents IFNγ release.

The same patient's NK cells were further assessed for their ability to kill allogeneic iDCs. As expected, HLH-NK cells were also unable to kill iDCs (Figure 4B). Importantly, however, the same iDCs used as targets in the cytolytic assay underwent maturation and increased the expression of CD83 (and CD86) following coculture with HLH-NK cells. Also in this case, NKp30 was responsible for the induction of DC maturation since its masking with specific mAbs abrogated DC maturation (Figure 4C).

Thus, in HLH-NK cells, although NKp30 fails to induce cytotoxicity, it retains the ability to transduce triggering signals resulting in the production of cytokines (such as TNFα) responsible for DC maturation. Indeed as shown in Figure 4D, following stimulation with plastic-bound anti-NKp30 mAbs, HLH-NK cells produced amounts of TNFα and IFNγ comparable with those detected in NK cells derived from healthy donors. Although not shown, control cultures containing NK cells stimulated by plastic-bound anti-CD56 mAbs did not contain detectable levels of any of the 2 cytokines.

Following the pioneering studies by Fernandez et al,27 demonstrating that DCs can induce antitumor NK-cell activity, a series of studies have recently highlighted the role of NK/DC interaction occurring during the early phases of acute tissue damage secondary to infection.11,12,15,19,27-31 This “cross-talk” may have important implications not only in the modulation of innate immune responses but also in shaping subsequent adaptive responses. As proposed previously, NK cells could be involved in the positive selection of mDCs11,21 that, after migration to secondary lymphoid compartments, induces priming of Th cells. Mature DCs optimal for Th priming are characterized not only by the expression of high levels of ligands for costimulatory receptors and HLA class II molecules, but also by the up-regulation of HLA class I molecules. NK cells would spare those DCs that after antigen (Ag) uptake express high levels of HLA class I molecules, while they would kill those DCs (recruited in inflamed tissues) that failed to undergo a full maturation. On the other hand, maturation of DCs may also be directly promoted or increased by cytokines released during the physical contact between DCs and activated NK cells. However the nature of the NK receptors involved in cytokine release during NK/DC interactions had remained still undefined. In this study, we show that following interaction with DCs, NKp30 is engaged and induces NK cells to secrete those cytokines (in particular TNFα) responsible for the induction of DC maturation. Indeed, mAb-mediated blocking of NKp30 strongly inhibited the NK-dependent DC maturation. Thus, NKp30, known to play a crucial role in triggering the NK-mediated killing of iDCs, is also primarily involved in the induction of cytokine release in NK/DC cocultures. Since DCs can produce large amounts of TNFα and IL12, in response to a wide range of stimuli, it is possible that, following NK/DC interaction, such cytokines could also be released by DCs through the engagement of the putative Nkp30-ligand (NKp30-L). Although we cannot rule out this possibility, our experiments would indicate that the engagement of the Nkp30-L is not a prerequisite for DC maturation, since the supernatant obtained from the sole NK cells, stimulated by anti-Nkp30 mAbs, could induce both DC maturation (Figure 2) and IL12 production (not shown). These events were promoted by TNFα produced by stimulated NK cells since both DC maturation (Figure 2A) and IL12 production (not shown) were inhibited when NK-derived supernatants were pretreated with specific anti-TNFα antibodies. In addition, the finding that HLA class I–specific inhibitory NK receptors can modulate the ability of NK cells to induce DC maturation would suggest an active role for NKp30 rather than for the NKp30-L. Clonal analysis indicated that only some NK cells may actually induce DC maturation. These NK cells are characterized either by the KIR– NKG2Amedium/low phenotype or by KIR+ phenotype displaying KIR/HLA class I mismatch (in the case of interaction with allogeneic DCs). Interestingly, they display the same phenotype as NK cells displaying cytolytic activity against iDCs.21

In conclusion, we show that a defined subset of NK cells (variable in size among different individuals) is involved in the process of DC maturation detectable in vitro upon coculture of activated NK cells and iDCs. This process might be important for complementing the NK-mediated editing of DCs imposed by the positive selection of mDCs, which is consequent to killing of iDCs. Both events are induced by the engagement of the NKp30 receptor by still undefined ligand(s) on DCs.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 22, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4035.

Supported by grants awarded by the European Union FP6, LSHB-CT-2004-503319-AlloStem; Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC); Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS); Ministero della Sanità; and Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR). Also supported by Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino, Italy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

The European Commission is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal