Abstract

The plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) expression can be enhanced by hypoxia and other stimuli leading to the mobilization of intracellular calcium. Thus, it was the aim of the present study to investigate the role of calcium in the hypoxia-dependent PAI-1 expression. It was shown that the Ca2+-ionophore A23187 and the cell permeable Ca2+-chelator BAPTA-am (1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid-acetoxymethyl ester) induced PAI-1 mRNA and protein expression under normoxia and hypoxia in HepG2 cells. Transfection experiments with wild-type and hypoxia response element (HRE)-mutated PAI promoter constructs revealed that the HRE binding hypoxiainducible factor-1 (HIF-1) mediated the response to A23187 and BAPTA-am. Although A23187 induced a striking and stable induction of HIF-1α, BAPTA-am only mediated a fast and transient increase. By using actinomycin D and cycloheximide we showed that A23187 induced HIF-1α mRNA expression, whereas BAPTA-am acted after transcription. Although A23187 activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), as well as protein kinase B, it appeared that the enhancement of HIF-1α by A23187 was only mediated via the ERK pathway. By contrast, BAPTA-am exerted its effects via inhibition of HIF-prolyl hydroxylase activity and von Hippel-Lindau tumor repressor protein (VHL) interaction. Thus, calcium appeared to have a critical role in the regulation of the HIF system and subsequent activation of the PAI-1 gene expression. (Blood. 2004;104:3993-4001)

Introduction

Plasminogen activator inhibitors (PAIs) appear to play a major regulatory role in physiologic processes such as fibrinolysis and tissue regeneration as well as a number of pathophysiologic conditions such as cancer metastasis, myocardial infarction, thrombosis, or type 2 diabetes. Among 2 identified inhibitors, PAI-1 and PAI-2, PAI-1 is the primary physiologic inhibitor of both tissue-type and urokinase-type plasminogen-activator (tPA and uPA, respectively). PAI-1, as a member of the SERPIN (Serine Protease Inhibitor) family, is a single chain, 50-kDa glycoprotein that can be produced by platelets, vascular endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and some other nonvascular cell types such as hepatocytes.1-3 Moreover, a factor known as protein C inhibitor (PCI), which can be synthesized in liver and some other steroid-responsive organs, was proposed to be named PAI-3.4

We and others have shown that PAI-1 gene expression can be induced by hypoxia via binding of the transcription factor hypoxiainducible factor-1 (HIF-1) to hypoxia response elements (HREs) in the PAI-1 gene promoter.5,6 HIF-1 is a heterodimer composed of HIF-1α and HIF-1β (arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator [ARNT]). Under normoxia, HIF-1α is constitutively degraded after binding the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein which targets HIF-1α for ubiquitination and proteasomal destruction.7,8 The binding of VHL to HIF-1α is specified by the hydroxylation of the key amino acids proline 402 and 564 in the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD) of HIF-1α. The hydroxylation reaction can be carried out by a family of newly identified HIF-1α prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs).9-12 Because the activity of these enzymes is aside from Fe2+, ascorbate, and 2-oxoglutarate, also dependent on the presence of O2, their activity decreases under hypoxia. Thus, under hypoxia HIF-1α is stabilized, accumulates, and translocates into the nucleus where it dimerizes with ARNT and binds to HREs in regulatory regions of target genes such as PAI-1.

In addition to hypoxia, several other stimuli have been shown to induce PAI-1 at the transcriptional level, including phorbol esters,13 inflammatory cytokines,14 transforming growth factor β,15 angiotensin, and insulin.16 An important intracellular messenger which has been implicated to have an effect on hypoxia- and hormone-dependent gene expression is intracellular calcium.17,18 Calcium ions (Ca2+) are released usually in response to inositol triphosphate (IP3) from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) serving as intracellular calcium store. However, it remains open whether an increase in Ca2+ as possibly observed under hypoxia may have an effect on HIF-1-dependent PAI-1 expression. Therefore, it was the aim of this study to investigate whether changes of intracellular Ca2+ achieved by the Ca2+-ionophore A23187 and the cell permeable Ca2+-chelator BAPTA-am (1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid-acetoxymethyl ester) influence PAI-1 gene expression via the transcription factor HIF-1.

Materials and methods

All biochemicals and enzymes were of analytical grade and from commercial suppliers. The calcium ionophore A23187, the cell-permeable calcium chelator BAPTA-am, and the cell-impermeable calcium chelator BAPTA were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). The specific inhibitors for mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) U0126 as well as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor LY294002 were from Cell Signaling (Frankfurt/M., Germany), the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor SP600125 was from Biomol (Heidelberg, Germany), and the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor SB203580 and the calmodulin kinase inhibitor KN93 were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA).

Cell culture

HepG2 cells were cultured in a normoxic atmosphere of 16% O2, 79% N2, and 5% CO2 (by vol) in minimum essential media (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) for 24 hours. At 24 hours medium was changed, and culture was continued at normoxia 16% O2 or at hypoxia 8% O2 (87% N2, 5% CO2 [by vol]).

Intracellular calcium [Ca2+]i measurement

HepG2 cells were treated with 10 μM Fura-2 am (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 1 hour under normoxia, then they were further cultured under normoxia or hypoxia in the presence of A23187, BAPTA-am, or BAPTA for 2 hours. Cells were then rinsed once with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS), and fluorescence was measured with an excitation wavelength at 340 nm and 380 nm and an emission wavelength at 520 nm. Autofluorescence from nontreated cells was subtracted, and the ratio R = I340/I380 of the fluorescence intensities was calculated as described.19

Plasmid constructs

The pGL3-hPAI-796 plasmid, containing the human PAI-1 promoter 5′-flanking region from -796 to +13, as well as the pGL3-hPAI-796-M2 construct with a mutation in the HRE was described.20 The pGL3-EPO-HRE luciferase plasmid, containing 3 erythropoietin (EPO)-HREs was described.21

The constructs for pG5E1B-LUC,22 pSG42423 and for Gal4-HIF1α-TADN (amino-terminal transactivation domain), Gal4-HIF1α-TADN mutant (TADNM),24-26 Gal4-HIF1α-TADC (carboxy-terminal transactivation domain), and Gal4-HIF1α-TADC mutant (TADCM)27 were already described. In Gal4-HIF1α-TADNM and Gal4-HIF1α-TADCM proline P564 or asparagine N803 was mutated to alanine, respectively.

The plasmids pGEX-HIF1α-TADN allowing generation of a N-terminal glutathione S transferase (GST)-tagged fusion protein encompassing amino acids 531 to 604 of rat HIF-1α and the plasmid pGEX4T3-p300CH1 were described.26,27 The construct pCMV-HA-VHL was a kind gift from Dr Patrick Maxwell (Imperial College, Renal Section, Hammersmith, London, United Kingdom).

RNA preparation and Northern blot analysis

Isolation of total RNA and Northern blot analysis were performed as described.5 Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense RNAs served as hybridization probes; they were generated by in vitro transcription from pBS-PAI1 using T3 polymerase or from pCRII-HIF1α and pBS-Actin using T7 polymerase. Blots were quantified with a videodensitometer (Biotech Fischer, Reiskirchen, Germany).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out as described.28 In brief, media or lysates from HepG2 cells were collected, and 100 μg protein was loaded onto a 10% or 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel and after electrophoresis and electroblotting to a methanol-activated polyvinylidene diflouride (PVDF) membrane, proteins were detected with a mouse monoclonal antibody against human PAI (1:100 dilution; American Diagnostics, Pfungstadt, Germany), a monoclonal antibody against human HIF-1α (1:2000; BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany), human β-Actin (1:10 000; Sigma), or human albumin (1:10 000; Sigma), a rabbit GAL4DBD antibody (1:5000, SC577; Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany), a monoclonal antibody against human phospho p42/p44 MAPK (1:1000; Cell Signaling), phospho p38 MAPK (1:1000; Cell Signaling), phospho Akt-T308 (1:1000; Cell Signaling), or phospho c-Jun-S73 (1:1000; Cell Signaling). The secondary antibody was either an anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) horseradish peroxidase (HRP; 1:5000; Sigma). The enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany) was used for detection.

Cell transfection and luciferase assay

About 4 × 105 HepG2 cells per 60-mm dish were transfected as described.16 In brief, 2.5 μg pGL3-hPAI-796 or pGL3-hPAI-796-M2 was transfected. Transfection efficiency was controlled by cotransfection of 0.25 μg Renilla luciferase expression vector (pRLSV40; Promega, Madison, WI). The detection of luciferase activity was performed with the Luciferase Assay Kit (Berthold, Pforzheim, Germany). To investigate HIF-1α transactivation, 2 μg reporter construct pG5-E1B-Luc was cotransfected with 500 ng Gal4-HIF1αTADN, Gal4-HIF1αTADC, or respective mutant constructs.26 After 5 hours medium was changed and cells were cultured under normoxia for 12 hours, then stimulated with 0.1 μM A23187 or 5 μM Bapta-am and further cultured for 24 hours under normoxia or hypoxia.

Purification of the GST-TADN and GST-p300CH1 fusion protein

The pGEX-GST-TADN, pGEX-4T3/p300CH1, or pGEX-5 × 1 transformed Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) were grown at 37°C in Luria Bertani (LB) media containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) for 4 hours. Then cells were harvested and GST-TADN, GST-p300CH1, and the GST proteins were prepared essentially as described.26 The integrity and yield of purified GST proteins were assessed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by Coomassie blue staining.

In vitro HIF-proline hydroxylase activity assay and GST pull-down assays

HepG2 cells cultured for 24 hours under normoxia were homogenized at 4°C in 250 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)-HCI (pH 7.5) supplemented with complete protease inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Then cell extracts were prepared as previously described.26 The cell extracts (300 μg protein/mL) were then incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes in 40 mM Tris-HCI (pH 7.5), 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 50 μM ammonium ferrous sulfate, 1 mM ascorbate, 2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 0.4 mg/mL catalase, 50 000 dpm [5-14C]2-oxoglutarate (Perkin Elmer, Langen, Germany), 0.1 mM unlabeled 2-oxoglutarate and either 20 μg GST protein or GST-TADN protein in the presence of CoCl2 or 5 μM BAPTA. The radioactivity associated to succinate was then determined as described.29 The basal GST-dependent activity in each experiment was subtracted from GST-TADN-dependent activity.

For the GST pull-down assays 35S-VHL or 35S-HIF1α protein was synthesized from the plasmid pCMV-HA-VHL or pcDNA3-HIF-1αV5His, respectively, using 35S-methionine and the TNT-coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). The GST-TADN and the GST-p300CH1 proteins were incubated with the cell extracts as for the hydroxylation assay either without or with CoCl2 or BAPTA, respectively. The reaction products were incubated at 4°C in 200 μL buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH = 8, 120 mM NaCl, and 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with glutathione-sepharose beads and 50.000 dpm [35S]-labeled human VHL or HIF-1α. After 2 hours, beads were washed 3 times with cold buffer (20 mM Tris-HCI, pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 0.5% NP-40). The bound proteins were eluted in 10 mM reduced glutathione and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography on a phosphoimager screen.26

Results

Induction of PAI-1 gene expression by A23187 and BAPTA-am

To investigate whether PAI-1 gene expression can be modulated by calcium ions, different agents, which can change the concentration of cytosolic calcium ions, were used. These include the specific calcium ionophore A23187 and the cell-permeable calcium chelator BAPTA-am. First, the intracellular calcium concentration [Ca2+]i was measured with Fura-2 am in cultured HepG2 cells. Hypoxia as well as A23187 enhanced [Ca2+]i by about 2.3- and 1.8-fold, respectively. By contrast, in the presence of BAPTA-am [Ca2+]i decreased by about 50%, whereas the noncell permeable BAPTA, as a control, had no effects on [Ca2+]i (Figure 1A).

Induction of PAI-1 gene expression by A23187 and BAPTA-am. (A) Measurement of intracellular cellular calcium [Ca2+]i. Cultured HepG2 cells were treated with Fura-2 am (10 μM) for 1 hour under normoxia (16% O2) and further cultured under normoxia or hypoxia (8% O2) with A23187 (5 μM), BAPTA-am (5 μM), or BAPTA (5 μM) for 2 hours. In each experiment [Ca2+]i at 16% O2 was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: P ≤ .05, compared with 16% O2. (B) HepG2 cells were treated with A23187 or BAPTA-am as in panel A and further cultured under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2). The PAI-1 mRNA measured after 4 hours or the PAI-1 protein level measured after 24 hours under hypoxia was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05, compared with the control at the same oxygen tension (pO2). (C) Representative Northern and Western blots. For Northern analysis 15 μg total RNA was hybridized to digoxigenin-labeled PAI-1 and β-actin antisense RNA probes (described in “Materials and methods”). Protein (50 μg) from the medium was subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against human PAI-1 or albumin, respectively. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.

Induction of PAI-1 gene expression by A23187 and BAPTA-am. (A) Measurement of intracellular cellular calcium [Ca2+]i. Cultured HepG2 cells were treated with Fura-2 am (10 μM) for 1 hour under normoxia (16% O2) and further cultured under normoxia or hypoxia (8% O2) with A23187 (5 μM), BAPTA-am (5 μM), or BAPTA (5 μM) for 2 hours. In each experiment [Ca2+]i at 16% O2 was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: P ≤ .05, compared with 16% O2. (B) HepG2 cells were treated with A23187 or BAPTA-am as in panel A and further cultured under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2). The PAI-1 mRNA measured after 4 hours or the PAI-1 protein level measured after 24 hours under hypoxia was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05, compared with the control at the same oxygen tension (pO2). (C) Representative Northern and Western blots. For Northern analysis 15 μg total RNA was hybridized to digoxigenin-labeled PAI-1 and β-actin antisense RNA probes (described in “Materials and methods”). Protein (50 μg) from the medium was subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against human PAI-1 or albumin, respectively. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.

In the following experiments, cultured HepG2 cells were stimulated with 5 μM A23187 or 5 μM BAPTA-am under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2), respectively, and PAI-1 expression was analyzed by Northern and Western blotting. Hypoxia induced PAI-1 mRNA expression about 3-fold in line with previous studies.5,30 Interestingly, both A23187 and BAPTA-am increased PAI-1 mRNA expression already under normoxia, whereas they were additive under hypoxia (Figure 1B). The mRNA enhancement mediated by hypoxia, A23187, or BAPTA-am was followed by an increase in protein levels (Figure 1B). Thus, both A23187 and BAPTA-am could enhance PAI-1 expression under normoxia and thus mimic hypoxia.

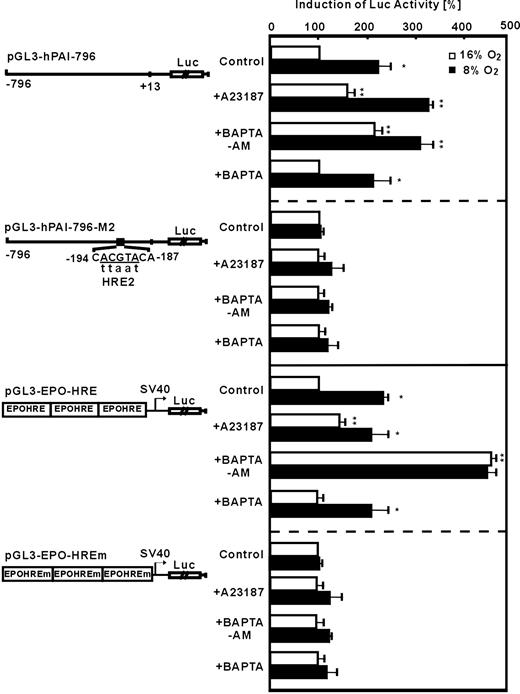

To find out whether A23187 and BAPTA-am mediated induction of PAI-1 via transcriptional regulation, especially via HIF-1, PAI-1 promoter reporter gene analyses were performed. In HepG2 cells transfected with the plasmid pGL3-hPAI-796 containing the wild-type human PAI-1 promotor, luciferase (Luc) activity was induced by about 2.3-fold under hypoxia (Figure 2). The treatment of transfected HepG2 cells with A23187 increased Luc activity by about 2- or 3-fold under normoxia or hypoxia, respectively. Similarly, BAPTA-am also enhanced Luc activity by about 2-fold under normoxia and by about 3-fold under hypoxia (Figure 3). The PAI-1 promotor construct pGL3-hPAI-796-M2 with a mutation of the HIF-1 binding site HRE-2 did not show the hypoxia- as well as the A23187- and BAPTA-am-mediated induction of Luc activity (Figure 2). Furthermore, in cells transfected with pGL3-EPO-HRE hypoxia as well as treatment with A23187 or BAPTA-am under normoxia induced LUC activity (Figure 2). Mutation of the HRE in pGL3-EPO-HREm abolished induction by hypoxia, A23187, and BAPTA-am (Figure 2). The specificity of the effect observed with BAPTA-am was ensured by using the cell impermeable BAPTA. It was found that BAPTA had no effects on PAI-1 promotor activity (Figure 2). These data indicate that intracellular calcium appears to affect PAI-1 expression via HIF-1.

Modulation of HIF-1-dependent PAI-1 promoter and EPO-HRE luciferase activity by A23187 and BAPTA-am. HepG2 cells were transfected with either luciferase (Luc) gene constructs driven by a wild-type 796-base pair (bp) human PAI-1 promoter (pGL3-hPAI-796), or the 796-bp promoter mutated at the HRE-2 (pGL3-hPAI-796-M2) site. In addition, Luc gene constructs containing 3 copies of the EPO HRE element in front of the simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter (pGl3EPO-HRE) or mutated EPO-HREm were used. The transfected cells were treated with A23187 (0.1 μM), BAPTA-am (5 μM), or BAPTA (5 μM) and further cultured 24 hours under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2). In each experiment the LUC activity of pGL3-hPAI-796, pGL3-hPAI-796-M2, pGL3-EPO-HRE, or pGL3-EPO-HREm transfected cells at 16% O2 was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05, versus 16% O2 in the same group, **P ≤ .05, versus the control groups at the same pO2.

Modulation of HIF-1-dependent PAI-1 promoter and EPO-HRE luciferase activity by A23187 and BAPTA-am. HepG2 cells were transfected with either luciferase (Luc) gene constructs driven by a wild-type 796-base pair (bp) human PAI-1 promoter (pGL3-hPAI-796), or the 796-bp promoter mutated at the HRE-2 (pGL3-hPAI-796-M2) site. In addition, Luc gene constructs containing 3 copies of the EPO HRE element in front of the simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter (pGl3EPO-HRE) or mutated EPO-HREm were used. The transfected cells were treated with A23187 (0.1 μM), BAPTA-am (5 μM), or BAPTA (5 μM) and further cultured 24 hours under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2). In each experiment the LUC activity of pGL3-hPAI-796, pGL3-hPAI-796-M2, pGL3-EPO-HRE, or pGL3-EPO-HREm transfected cells at 16% O2 was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05, versus 16% O2 in the same group, **P ≤ .05, versus the control groups at the same pO2.

Time-dependent modulation of HIF-1α protein expression by A23187 and BAPTA-am. (A) HepG2 cells were incubated under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) or treated with A23187 (5 μM) or BAPTA-am (5 μM) under normoxia (16% O2) and then harvested at different time points. HIF-1α protein was detected by Western blot analysis. The expression of HIF-1α under hypoxia at 4 hours was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. (B) Western blot analysis. Protein (100 μg) from HepG2 cells treated with A23187 (5 μM), BAPTA-am (5 μM), or BAPTA (5 μM) for 4 hours was subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against HIF-1α or β-actin. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.

Time-dependent modulation of HIF-1α protein expression by A23187 and BAPTA-am. (A) HepG2 cells were incubated under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) or treated with A23187 (5 μM) or BAPTA-am (5 μM) under normoxia (16% O2) and then harvested at different time points. HIF-1α protein was detected by Western blot analysis. The expression of HIF-1α under hypoxia at 4 hours was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. (B) Western blot analysis. Protein (100 μg) from HepG2 cells treated with A23187 (5 μM), BAPTA-am (5 μM), or BAPTA (5 μM) for 4 hours was subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against HIF-1α or β-actin. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.

Induction of HIF-1α expression by the calcium ionophore A23187 and the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-am

Because mutation of the HRE in the PAI-1 promotor and in the EPO-HRE construct abolished A23187- and BAPTA-am-mediated induction, it seemed likely that both compounds exert their effects on HIF-1α. To investigate this, HepG2 cells were treated with A23187 and BAPTA-am, and the level of HIF-1α protein was determined by Western blot. When HepG2 cells were treated with A23187 (5 μM) and BAPTA-am (5 μM) for 4 hours, HIF-1α protein levels were induced under normoxia and under hypoxia. The non-cell-permeable BAPTA had no effects (Figure 3). The enhancement of HIF-1α by A23187 and BAPTA-am under normoxia proceeded in a manner slightly different from that mediated by hypoxia. The hypoxia-dependent induction of HIF-1α was clearly visible after 2 hours and reached maximal values after 4 hours. Then, HIF-1α levels remained stable until 12 hours, when they started to decline. Although both A23187 and BAPTA-am also increased HIF-1α maximally after 4 hours under normoxia, stimulation with A23187 caused a more precipitous and stable induction of HIF-1α with dramatically high levels until 24 hours, whereas HIF-1α strikingly decreased already 4 hours after BAPTA-am treatment (Figure 3). This suggested that these 2 different compounds, which could, respectively, increase or decrease the intracellular calcium concentration, might influence the HIF-1α levels via different mechanisms.

Given the striking and stable induction of HIF-1α after treatment with the calcium ionophore A23187, we aimed to investigate whether this enhancement of HIF-1α levels was due to transcriptional or posttranscriptional regulation. To do this, HepG2 cells were pretreated with the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (Act D) or translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) for 30 minutes prior to stimulation with A23187. Although CHX completely abolished the hypoxia-dependent HIF-1α protein induction, Act D only reduced it by about 50%. However, both Act D and CHX significantly reduced A23187-induced HIF-1α protein levels (Figure 4A). These results indicated that the induction of HIF-1α by A23187 needed de novo synthesis of both HIF-1α mRNA and protein in the cells. In addition, we studied the mechanism of HIF-1α induction by the cell-permeable calcium chelator BAPTA-am. It was found that pretreatment with CHX inhibited HIF-1α induction mediated by both hypoxia and BAPTA-am (Figure 4C). In contrast to the A23187 treatment, BAPTA-am could still induce HIF-1α protein levels in the presence of Act D (Figure 4C). To further confirm this, HIF-1α mRNA expression was detected by Northern blot analysis. We found that hypoxia up-regulated HIF-1α mRNA abundance by about 2-fold (Figure 5). Treatment with A23187 induced HIF-1α mRNA expression by about 2.6-fold under normoxia and by about 3-fold under hypoxia, indicating that A23187 mimicked hypoxia (Figure 5). By contrast, treatment with BAPTA-am did not show significant increases in HIF-1α mRNA abundance under both normoxia and hypoxia (Figure 5). These results show that the calcium ionophore A23187 induced HIF-1α expression mainly transcriptionally and that BAPTA-am exerted its effects after transcription.

Modulation of A23187- and BAPTA-am-dependent HIF-1α induction by Act D and CHX. HepG2 cells were pretreated with Act D (5 μg/mL) or CHX (10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes, then stimulated with A23187 (5 μM) or BAPTA-am (5 μM) under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) for 4 hours. HIF-1α protein was detected by Western blot analysis. (A,C) The expression of HIF-1α under hypoxia was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ 0.05 versus controls at the same pO2; **P ≤ .05 versus A23187 treatment group at the same pO2. (B,D) Representative Western blot. Protein (100 μg) from the whole-cell extract was subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against HIF-1α or β-actin. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.

Modulation of A23187- and BAPTA-am-dependent HIF-1α induction by Act D and CHX. HepG2 cells were pretreated with Act D (5 μg/mL) or CHX (10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes, then stimulated with A23187 (5 μM) or BAPTA-am (5 μM) under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) for 4 hours. HIF-1α protein was detected by Western blot analysis. (A,C) The expression of HIF-1α under hypoxia was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ 0.05 versus controls at the same pO2; **P ≤ .05 versus A23187 treatment group at the same pO2. (B,D) Representative Western blot. Protein (100 μg) from the whole-cell extract was subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against HIF-1α or β-actin. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.

Modulation of HIF-1α mRNA expression by A23187 and BAPTA-am. HepG2 cells were stimulated with A23187 (5 μM) or BAPTA-am (5 μM) under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) for 4 hours. HIF-1α mRNA was detected by Northern blot analysis. (A) The expression of HIF-1α mRNA under hypoxia was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05, 16% O2 versus 8% O2;**P ≤ .05, +A23187 versus control at the same pO2. (B) Representative Northern blot analysis. Total RNA (20 μg) of each sample was subjected to Northern blot analysis with HIF-1α or β-actin antisense RNA probes. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.

Modulation of HIF-1α mRNA expression by A23187 and BAPTA-am. HepG2 cells were stimulated with A23187 (5 μM) or BAPTA-am (5 μM) under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) for 4 hours. HIF-1α mRNA was detected by Northern blot analysis. (A) The expression of HIF-1α mRNA under hypoxia was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05, 16% O2 versus 8% O2;**P ≤ .05, +A23187 versus control at the same pO2. (B) Representative Northern blot analysis. Total RNA (20 μg) of each sample was subjected to Northern blot analysis with HIF-1α or β-actin antisense RNA probes. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.

Involvement of p42/p44 MAPK in the induction of HIF-1α by the calcium ionophore A23187

In a next step, it was checked what signaling cascade might be responsible for HIF-1α induction by the calcium ionophore A23187. To do this, HepG2 cells were treated with different specific inhibitors of p42/p44 MAPK, p38 MAPK, JNK, PI3K, and calmodulin kinase 30 minutes before A23187 was added for 4 hours. We found that U0126, the inhibitor of p42/p44 MAPK, decreased both the hypoxia-dependent and the A23187-dependent induction of HIF-1α (Figure 6A). In contrast, SB203580, a p38 MAPK inhibitor, slightly reduced hypoxia- and A23187-dependent induction of HIF-1α (Figure 6B). Although the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 only reduced hypoxia-dependent HIF-1α levels, KN93, a calmodulin kinase inhibitor, had no effect on A23187- or hypoxia-dependent HIF-1α induction (Figure 6C-E).

A23187 induces HIF-1α via activation of p42/p44 ERK. HepG2 cells were pretreated for 30 minutes with different kinase inhibitors U0126 (A), SB203580 (B), SP SP600125 (C), LY294002 (D), or KN93 (E), followed by the treatment with A23187 (5μM). Cells were further cultured under normoxia or hypoxia. Proteins were harvested after 4 hours for HIF-1α and after 15 minutes for the respective kinase blot and detected by Western blotting with antibodies against phospho-p44/42-ERK, phospho-p38, phospho-Jun, and phospho-Akt (see “Materials and methods”).

A23187 induces HIF-1α via activation of p42/p44 ERK. HepG2 cells were pretreated for 30 minutes with different kinase inhibitors U0126 (A), SB203580 (B), SP SP600125 (C), LY294002 (D), or KN93 (E), followed by the treatment with A23187 (5μM). Cells were further cultured under normoxia or hypoxia. Proteins were harvested after 4 hours for HIF-1α and after 15 minutes for the respective kinase blot and detected by Western blotting with antibodies against phospho-p44/42-ERK, phospho-p38, phospho-Jun, and phospho-Akt (see “Materials and methods”).

Furthermore, hypoxia and even more pronounced A23187 mediated an enhancement of phospho-p42/p44 levels in HepG2 cells (Figure 6A). Pretreatment of cells with the p42/p44 MAPK inhibitor U0126 completely abolished hypoxia- and A23187-induced phospho-p42/p44 levels (Figure 6A). We further found that hypoxia and A23187 treatment increased p38 MAPK phosphorylation. Further, A23187 induced Jun and protein kinase B (PKB) phosphorylation which was reduced by the inhibitors SP600125 and LY294002, respectively (Figure 6B-D). Together these results suggest that activation of p42/p44 MAPK seems to be involved in the calcium ionophore A23187-dependent induction of HIF-1α expression.

Inhibition of HIF-1α prolyl hydroxylase activity by the calcium chelator BAPTA-am

The results from our experiments with Act D and BAPTA-am led to the hypothesis that intracellular calcium can act also after transcription, influencing HIF-1α transactivation or stability. There are 2 transactivation domains (TADs) present in HIF-1α, referred to as TADN and TADC. To investigate whether A23187 and BAPTA-am may interfere with HIF-1α transactivation, HepG2 cells were cotransfected with the luciferase reporter construct pG5-E1B-Luc that contains 5 copies of a Gal4 response element and vectors allowing expression of fusion proteins consisting of the Gal4-DNA binding domain (Gal4) and either HIF-1α TADN or TADC.

We found that HIF-1α TADN and TADC transactivity could be significantly induced by hypoxia in line with previous studies.24-26,31,32 Treatment with BAPTA-am under normoxia also increased HIF-1α TADN activity by about 2-fold, whereas A23187 had no effect. Neither BAPTA-am nor A23187 had any effect on TADC transactivity (Figure 7A). It has been well demonstrated that the key amino acid proline 564 in the TADN plays a crucial role in HIF-1α stabilization.25,33-36 It can be hydroxylated by HIF prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) under normoxia, thereby mediating the interaction of HIF1α and VHL which then targets HIF-1α for proteasomal degradation. The mutation of the critical amino acid proline (P564) in the construct Gal4-HIF1αTADNM, which led to a hydroxylation-resistant fusion protein, caused an increase in transactivity under normoxia and a loss of the response to hypoxia and BAPTA-am (Figure 7A). Furthermore, asparagine (N803) in HIF-1α TADC can also be hydroxylated by another hydroxylase named FIH (factor-inhibiting HIF) and thus block the interaction of HIF-1α and p300/CBP (CREB [cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein]-binding protein).27,37,38 Although this mutation of asparagine 803 to alanine enhanced transactivation, it also abolished hypoxic induction. Again, neither BAPTA-am nor A23187 had any effect on TADC activity (Figure 7A).

Induction of HIF-1α transactivation by BAPTA-am via inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase activity. (A) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with a luciferase reporter construct pG5-E1B-LUC and different fusion gene constructs in which the Gal4 DNA binding domain was fused to either the HIF-1α region from amino acid 532 to 585 containing TADN or 727 to 826 containing TADC, respectively, as shown on the left side of panel A. After 24 hours the transfected cells were treated with either 5 μM BAPTA-am or 0.1 μM A23187 under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) for 24 hours. Values are means ± SEM of 6 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05 versus control in the same group. (B) Western blot analysis. Protein (50 μg) from HepG2 cells transfected with wild-type and mutated Gal4-HIF1αTADN and Gal4-HIF1αTADC constructs was treated with BAPTA-am (5 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM) for 4 hours and then subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against Gal4DBD. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence. (C) In vitro prolyl hydroxylase activity assay. The GST-HIF1α-TADN fusion protein or the GST protein was incubated with HepG2 cell extract, cofactors, and [5-14C]2-oxoglutarate in the presence of CoCl2 (10 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM). The radioactivity associated to 14C-succinate was determined. In each experiment the basal HIF-TADN-dependent activity (control) was set to 100% after normalized by subtracting the GST-associated activity. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05 versus control. (D) GST pull-down assay. HepG2 cells were treated with or without BAPTA-am (5 μM). Cell extracts were prepared and incubated with the GST-HIF1α-TADN fusion protein in the presence of CoCl2 (10 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM) supplemented with cofactors. Glutathione-Sepharose beads and [35S]VHL were then added, and the bound VHL was recovered, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized by phosphoimaging. The input remains from directly loaded [35S]VHL. The 2 bands represent the 213- and 160-amino acid VHL translation products. Representative data of 3 individual experiments. (E) GST pull-down assay. Cell extracts were incubated as in panel D with the GST-p300CH1 protein and [35S]HIF-1α, and the bound HIF-1α was recovered, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized by phosphoimaging. The input remains from directly loaded [35S]HIF-1α.

Induction of HIF-1α transactivation by BAPTA-am via inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase activity. (A) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with a luciferase reporter construct pG5-E1B-LUC and different fusion gene constructs in which the Gal4 DNA binding domain was fused to either the HIF-1α region from amino acid 532 to 585 containing TADN or 727 to 826 containing TADC, respectively, as shown on the left side of panel A. After 24 hours the transfected cells were treated with either 5 μM BAPTA-am or 0.1 μM A23187 under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) for 24 hours. Values are means ± SEM of 6 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05 versus control in the same group. (B) Western blot analysis. Protein (50 μg) from HepG2 cells transfected with wild-type and mutated Gal4-HIF1αTADN and Gal4-HIF1αTADC constructs was treated with BAPTA-am (5 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM) for 4 hours and then subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against Gal4DBD. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence. (C) In vitro prolyl hydroxylase activity assay. The GST-HIF1α-TADN fusion protein or the GST protein was incubated with HepG2 cell extract, cofactors, and [5-14C]2-oxoglutarate in the presence of CoCl2 (10 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM). The radioactivity associated to 14C-succinate was determined. In each experiment the basal HIF-TADN-dependent activity (control) was set to 100% after normalized by subtracting the GST-associated activity. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05 versus control. (D) GST pull-down assay. HepG2 cells were treated with or without BAPTA-am (5 μM). Cell extracts were prepared and incubated with the GST-HIF1α-TADN fusion protein in the presence of CoCl2 (10 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM) supplemented with cofactors. Glutathione-Sepharose beads and [35S]VHL were then added, and the bound VHL was recovered, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized by phosphoimaging. The input remains from directly loaded [35S]VHL. The 2 bands represent the 213- and 160-amino acid VHL translation products. Representative data of 3 individual experiments. (E) GST pull-down assay. Cell extracts were incubated as in panel D with the GST-p300CH1 protein and [35S]HIF-1α, and the bound HIF-1α was recovered, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized by phosphoimaging. The input remains from directly loaded [35S]HIF-1α.

The induction of HIF-1α TADN transactivity by BAPTA-am indicated that the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-am might accumulate HIF-1α through protein stabilization. To test this we measured the Gal4-TADN and -TADC protein levels. In line with the transfection assays hypoxia and BAPTA-am enhanced Gal4-HIF-1αTADN levels, whereas the levels of the degradation resistant Gal4-HIF1αTADNM (P564A) were enhanced and no longer regulated by hypoxia or BAPTA-am. In contrast, the Gal4-HIF1αTADC and Gal4-HIF1αTADCM (N803A) protein levels were not regulated by hypoxia in line with other studies24,32,39 and BAPTA-am (Figure 7B).

Because the PHD-dependent proline hydroxylation within TADN appears to be a critical step for HIF-1α stabilization, the following experiments aimed to investigate the effects of BAPTA-am on HIF-PHD activity by an in vitro hydroxylation assay and VHL-GST pull-down assay. The results show that treatment of cells with BAPTA-am (5 μM) was enough to inhibit HIF-PHD activity (Figure 7B) and to reduce the interaction with VHL (Figure 7C). The additional presence of BAPTA in the in vitro hydroxylation reaction did not further inhibit VHL binding (Figure 7C). Similarly, the addition of Co2+ which was used as a positive control also led to a reduction of hydroxylase activity and VHL binding (Figure 7C-D). To further clarify that BAPTA-am did not act on FIH and thus on TADC we performed pull-down assays with a GST-p300CH1 fusion protein and 35S-labeled HIF-1α. Although cobalt chloride enhanced the interaction with the p300CH1 protein, BAPTA-am had no effect (Figure 7E). These data together with the transfection assays again indicate that BAPTA-am appeared not to affect hydroxylation of N803. Thus, BAPTA-am appears to influence HIF-1α protein stability via inhibition of HIF-PHD activity.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that both the calcium ionophore (A23187) and the cell-permeable calcium chelator (BAPTA-am) stimulated the expression of PAI-1 via enhancement of HIF-1α in HepG2 cells. A23187 acted by inducing HIF-1α transcription via the ERK pathway and BAPTA-am acted after translation by inhibiting HIF-PHD activity and VHL binding and thus preventing HIF-1α from proteasomal degradation.

Signaling pathways modulating HIF-1 activity

The signaling pathways and mechanisms involved in the activation of HIF-1 are not understood to the last detail. Oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylation9,34 and asparginyl hydroxylation27 have been shown to be of major importance for HIF-α-subunit protein stability and coactivator recruitment. Under hypoxia, HIF-1α accumulation is mainly caused by protein stabilization via the inhibition of HIF PHDs, thereby blocking VHL-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. In addition to this oxygen-dependent response, HIF-1α protein levels under normoxic conditions can also be enhanced by insulin, angiotensin, nitric oxide (NO), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and thrombin.16,40-43 This indicates that different signaling pathways may contribute to the accumulation of HIF-1α. Although a complete consensus regarding the role of calcium has not been reached so far,44,45 it appeared that mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases20,46 and the PI3K/PKB pathway47,48 were involved in the regulation of HIF-1 activity.

Involvement of calcium in the activation of HIF-1α and PAI-1 expression

In this study, it was demonstrated that the induction of HIF-1α by A23187 was due to enhanced de novo transcription because it could be significantly inhibited by actinomycin D and an increased amount of HIF-1α mRNA was detected. Further, we showed that elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ by A23187 activated the p42/p44 MAPK pathway and that the specific MEK inhibitor U0126 inhibited this activation as well as induction of HIF-1α protein expression. These results are in line with a study showing that activation of protein kinase C (PKC)/ERK by angiotensin II increased HIF-1α in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs).49 Similar to our study, another Ca2+ ionophore, ionomycin, was able to enhance HRE-regulated luciferase activity and the involvement of ERK was proposed,45 but those investigations did not examine whether the HIF-1α response was due to transcriptional mechanisms.

In contrast to our study, the A23187-mediated HIF-1α induction could not be detected in A549 lung epithelial carcinoma cells.50 Instead, that investigation showed cooperation of HIF-1α with activator protein-1 (AP-1), implicating signaling via JNK. However, neither our study using a JNK inhibitor nor another study45 could show an involvement of this pathway.

Moreover, calmodulin kinases (CaMKs) can act as upstream components of ERK.51,52 Interestingly, neither our study nor previous studies45,50 could confirm the involvement of CaMK because the CaMK inhibitors had no effect on A23187- or hypoxia-induced gene expression. Thus, despite contradictory, evidence exists whether the ras/raf pathway is53 or is not54 involved in hypoxic gene expression, it seems likely that this pathway may contribute to Ca2+-dependent activation of ERK, leading to HIF-1α induction.

Furthermore, application of actinomycin D also inhibited hypoxia-induced HIF-1α accumulation by about 50%, implicating that hypoxia regulates HIF-1α mRNA transcription. Although HIF-1α mRNA was regarded to be constitutively expressed in cultured cells independent of oxygen tensions,55 we and others21,56,57 found that this appeared not to be the fact because an induction of HIF-1α mRNA expression was detected under hypoxia. A reason may be differences between cell types because they may express a different combination of signaling proteins, including MAPKs, which could be activated by the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ in HepG2 cells, but not in other cell types such as Hep3B44 and A549 cells.50 This could explain the contradictory results obtained between this study and other reports in which Ca2+ could not induce HIF-1α protein levels in Hep3B and A549 cells.44,50 However, as we and another study with HepG2 cells showed,45 hypoxia-induced phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK might be involved in HIF-1α accumulation under hypoxia as well as in response to A23187.

Furthermore, BAPTA-am, the intracellular Ca2+ chelator, could also enhance HIF-1α, but its effect was much more transient compared with A23187 and hypoxia. We propose that BAPTA-am accumulates HIF-1α through protein stabilization but not via stimulation of HIF-1α gene transcription, based on the following findings. First, treatment with BAPTA-am did not enhance HIF-1α mRNA expression, and accumulation of HIF-1α by BAPTA-am could not be blocked by actinomycin D. Second, the HIF-1α prolyl hydroxylation assay and GST pull-down analysis revealed that BAPTA-am inhibited PHD activity and thereby the interaction between HIF-1α and VHL. Thus, our findings are in line with a study showing that EGTA-am (ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid-acetoxy-methyl ester), another intracellular Ca2+ chelator, accumulated HIF-1α in Hep3B cells.44 The observed effects for BAPTA-am appear to be specific for HIF-PHDs and not to affect FIH because BAPTA-am did not affect TADC transactivation or p300CH1 binding (Figure 7). However, our findings with BAPTA-am are contrasted by a study with HepG2 cells45 and A549 lung epithelial carcinoma cells.50 Both studies could not show BAPTA-am-dependent accumulation of HIF-1α. The reason for this difference seems to be because in the other HepG2 cell study BAPTA-am was used at 40 μM for 16 hours,45 and the A549 cells were treated with 10 μM for 20 hours,50 whereas our study clearly showed that the HIF-1α increase was transient with a maximum at 4 hours (Figure 2). Thus, our study showed for the first time that Ca2+ might affect HIF-dependent genes via modulation of PHD activity.

Calcium-dependent PAI-1 gene expression under physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions

The direct involvement of HIF-1α in the Ca2+-mediated PAI-1 expression has not been shown before. However, the proposal that Ca2+ may function as messenger in PAI-1 expression came from studies with the human histiocytic cell line U937 and HUVECs in which the Ca2+-ionophore A23187 and thapsigargin increased PAI-158,59 in line with the present study. Further evidence that Ca2+ may have an effect on PAI-1 expression came from studies investigating the angiotensin II (Ang-II)-dependent PAI-1 expression in the human placental cell line HTR8-S/SVneo.60 But in contrast to our study, those experiments showed a Ca2+-dependent activation of calcineurin and the involvement of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT).60

The signaling pathway mediating the Ca2+-dependent HIF-1α induction was shown to be the ERK-MAPK pathway. Further, our study is in line with another report showing that hypoxia as well as A23187 mediates an increase of intracellular Ca2+ and an activation of ERK.45 Additionally, the participation of the ERK pathway in the A23187-dependent PAI-1 induction in this study is in line with a recent report on the Ang-II-mediated PAI-1 expression in VSMCs.61 Although the latter study did not investigate the direct involvement of Ca2+ in Ang-II-dependent PAI-1 expression, it was shown that the Ang-II-dependent PAI-1 promoter activation requires the coactivation of specific β-1 glycoprotein (SP-1) and AP-1.61 Thus, it appears that, depending on the stimulus and the cell type downstream from ERK, different transcription factors may activate PAI-1 expression.

Induction of PAI-1 expression by Ca2+ via HIF-1α may have some importance in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular or renal diseases as well as in tumor development. Enhanced PAI-1 levels and thus inhibition of fibrinolysis is important for thrombus formation and stabilization and may thus promote progression of ischemic coronary heart disease and fibrin deposition on venous valves during thromboembolic events. In addition, the HIF-1-mediated PAI-1 expression appears to be involved in vascularization of tumor tissue by preventing excessive proteolysis and thus enabling coordinated endothelial cell sprouting.62,63 Thus, the inhibition of Ca2+ and HIF-1-induced PAI-1 induction by a novel type of Ca2+ antagonist might be an interesting task for the future.

In summary, our study has shown that the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 induced PAI-1 expression via the ERK pathway and transcriptional induction of HIF-1α, whereas BAPTA-am mediated a transient HIF-1α accumulation via inhibition of PHD activity with subsequent induction of PAI-1 expression.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 24, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1017.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 402 Teilprojekt A1, GRK 335) and the Forschungsförderprogramm of the University Göttingen.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr T.D. Gelehrter (Department of Human Genetics, University Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI) for the gift of PAI-1 cDNA and Dr P. Maxwell for the kind gift of the pCMV-HA-VHL construct.

![Figure 1. Induction of PAI-1 gene expression by A23187 and BAPTA-am. (A) Measurement of intracellular cellular calcium [Ca2+]i. Cultured HepG2 cells were treated with Fura-2 am (10 μM) for 1 hour under normoxia (16% O2) and further cultured under normoxia or hypoxia (8% O2) with A23187 (5 μM), BAPTA-am (5 μM), or BAPTA (5 μM) for 2 hours. In each experiment [Ca2+]i at 16% O2 was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: P ≤ .05, compared with 16% O2. (B) HepG2 cells were treated with A23187 or BAPTA-am as in panel A and further cultured under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2). The PAI-1 mRNA measured after 4 hours or the PAI-1 protein level measured after 24 hours under hypoxia was set to 100%. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05, compared with the control at the same oxygen tension (pO2). (C) Representative Northern and Western blots. For Northern analysis 15 μg total RNA was hybridized to digoxigenin-labeled PAI-1 and β-actin antisense RNA probes (described in “Materials and methods”). Protein (50 μg) from the medium was subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against human PAI-1 or albumin, respectively. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence and scanned by videodensitometry.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/13/10.1182_blood-2004-03-1017/6/m_zh80240470700001.jpeg?Expires=1769204320&Signature=ty341KXA6SdM4cUksN-LPd09ufdsoAhKlWbL3frRidpEhbj8vh1beTxJzC5KIEG6G0hKbPSbdWRMoIvUJEqGe3MKh6lJmdKrwdmdbveMtPKyTHPnsy5ebSFl27eEjGks7H98ICi0Ub13m-zbI7W3SXt~sxVJSPJ6yztrGZMP6Ql6slqE2p-FKgPfaIKpC9H1CxwvpHhJG6g~7WS2dSB5xcbRP-WGqSApuLFElnp8pzebYS~v5bEwOOQjJvjtvgidu8POdAYGEmvUGkaM0XRz9kHHuWH5UNcvrOTy8Vj7VR1p3XmKlqGVFRApiTcGLxNMBsSC0FMuQmIEoUinUDfAcQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Induction of HIF-1α transactivation by BAPTA-am via inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase activity. (A) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with a luciferase reporter construct pG5-E1B-LUC and different fusion gene constructs in which the Gal4 DNA binding domain was fused to either the HIF-1α region from amino acid 532 to 585 containing TADN or 727 to 826 containing TADC, respectively, as shown on the left side of panel A. After 24 hours the transfected cells were treated with either 5 μM BAPTA-am or 0.1 μM A23187 under normoxia (16% O2) or hypoxia (8% O2) for 24 hours. Values are means ± SEM of 6 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05 versus control in the same group. (B) Western blot analysis. Protein (50 μg) from HepG2 cells transfected with wild-type and mutated Gal4-HIF1αTADN and Gal4-HIF1αTADC constructs was treated with BAPTA-am (5 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM) for 4 hours and then subjected to Western analysis with an antibody against Gal4DBD. Autoradiographic signals were obtained by chemiluminescence. (C) In vitro prolyl hydroxylase activity assay. The GST-HIF1α-TADN fusion protein or the GST protein was incubated with HepG2 cell extract, cofactors, and [5-14C]2-oxoglutarate in the presence of CoCl2 (10 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM). The radioactivity associated to 14C-succinate was determined. In each experiment the basal HIF-TADN-dependent activity (control) was set to 100% after normalized by subtracting the GST-associated activity. Values are means ± SEM of 3 independent culture experiments. Statistics, Student t test for paired values: *P ≤ .05 versus control. (D) GST pull-down assay. HepG2 cells were treated with or without BAPTA-am (5 μM). Cell extracts were prepared and incubated with the GST-HIF1α-TADN fusion protein in the presence of CoCl2 (10 μM) or BAPTA (5 μM) supplemented with cofactors. Glutathione-Sepharose beads and [35S]VHL were then added, and the bound VHL was recovered, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized by phosphoimaging. The input remains from directly loaded [35S]VHL. The 2 bands represent the 213- and 160-amino acid VHL translation products. Representative data of 3 individual experiments. (E) GST pull-down assay. Cell extracts were incubated as in panel D with the GST-p300CH1 protein and [35S]HIF-1α, and the bound HIF-1α was recovered, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and visualized by phosphoimaging. The input remains from directly loaded [35S]HIF-1α.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/104/13/10.1182_blood-2004-03-1017/6/m_zh80240470700007.jpeg?Expires=1769204320&Signature=3tLU~eM-tWQe11ERW~sRm-CnjZuWtLbtBb1Gxf6k-qvBR1I3JQnS3yK98I5~MGFNjsThfZ6qXwsRAtC-~TXHRdSR5meKP8UKdBnJbvnd1HZFOuYElswHFX9WFNK3zKuIUfeklQOU4Bojgu70OWVuB8iQT2jbn~dRnMrMjZpZjZt9gpYOKb8Z0FvP49YSGbaxUVKFKkaY8FEbcEELCly4cHhFSMoAYxSRXZ82RkTvni-N-SH3F0YDmuodJl8xAFNSkqX6i0Xvfhsui3A1wf3FTndX2XFQSENX-1HJ55K~UKMVWbEUcm8p2WVheCW4wLhfUrLisMgSCqRTAjoh65x16g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal