Chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) requires long-term immunosuppressive therapy after hematopoietic cell transplantation. We retrospectively analyzed a cohort of 751 patients with chronic GVHD to identify characteristics associated with the duration of immunosuppressive treatment. Among the 274 patients who discontinued immunosuppressive therapy after resolution of chronic GVHD before recurrent malignancy or death, the median duration of treatment was 23 months. Results of a multivariable model showed that treatment was prolonged in patients who received peripheral blood cells, in male patients with female donors, in those with graft-versus-host HLA mismatching, and in those with hyperbilirubinemia or multiple sites affected by chronic GHVD at the onset of the disease. Nonrelapse mortality was increased among patients with HLA mismatching or hyperbilirubinemia but not among those with other risk factors associated with prolonged treatment for chronic GVHD. Nonrelapse mortality was also increased in older patients and those with older donors, in patients with platelet counts less than 100 000/μL or progressive onset of chronic GVHD from acute GVHD, and in those receiving higher doses of prednisone immediately before the diagnosis of chronic GVHD. After the dose of prednisone was taken into account, progressive onset was not associated with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality.

Introduction

Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) represents one of the major complications of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Patients with chronic GVHD have decreased performance, impaired quality of life, and increased risk of mortality.1,2 Systemic treatment may not be necessary when a single site is affected and symptoms are mild. If symptoms are severe or if multiple sites are involved, long-term immunosuppressive treatment is generally required to control the disease.3,4 Previous studies have shown that 30% to 70% of all patients surviving beyond 100 days after HCT require treatment for chronic GHVD,2,4-6 often for more than 2 years.2,5,7-9 Chronic GVHD and long-term glucocorticoid treatment impair immune function and increase the risk of opportunistic infections.4,6 Patients may experience other glucocorticoid therapy-related complications, including avascular necrosis, glucose intolerance, hypertension, weight gain, changes in body habitus, cataracts, osteoporosis, myopathy, and disturbances of mood and sleep.10

Previous studies have identified risk factors for chronic GVHD after HCT, including prior acute GVHD, older patient age, use of female donors for male recipients, use of donor lymphocyte infusion, and the use of unrelated or HLA-mismatched donors.11-19 More recently, Cutler et al20 confirmed in a meta-analysis that the risk of chronic GVHD was increased among patients who received mobilized blood cells as opposed to marrow as a source of stem cells. Previous studies have also identified characteristics consistently associated with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality among patients with chronic GVHD. These include involvement of multiple body sites, thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100 000/μL) at the time of diagnosis, and progressive onset of chronic GVHD from prior acute GVHD.3,21-25

Risk factors and disease characteristics associated with the duration of treatment for chronic GVHD have been examined in one previous retrospective study of 82 patients.26 In that study, the prior occurrence of grades III to IV acute GVHD was the only factor that was associated with a longer duration of treatment for chronic GVHD. Discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy in the absence of recurrent malignancy has been used as a surrogate end point indicating resolution of chronic GVHD in at least one prospective clinical trial.9 To facilitate the design of future clinical trials, we retrospectively analyzed data from a large cohort of patients with chronic GVHD in an attempt to identify characteristics associated with the duration of immunosuppressive treatment.

Patients and methods

Immunosuppressive treatment

Patients who received HCT after myeloablative conditioning between January 1994 and December 2000 and subsequently required systemic immunosuppressive treatment for chronic GVHD were included in this study. All patients included in the analysis signed forms approved by the Institutional Review Board documenting informed consent to participate in clinical trials and to allow the use of medical records for research. Matching of the donor and recipient was assessed according to available typing of HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 antigens and alleles. Chronic GVHD was diagnosed and staged according to previously published criteria.3,4

Chronic GVHD was generally treated with prednisone and continued administration of cyclosporine. Patients who had participated in randomized clinical trials comparing cyclosporine versus tacrolimus for prevention of acute GVHD continued administration of the same calcineurin inhibitor after the onset of chronic GVHD. Prednisone was administered initially at a dose of 1 mg/kg/d for at least 2 weeks unless patients were already being treated with higher doses of prednisone immediately before the onset of chronic GVHD. In all patients, the dose of prednisone was tapered over 6 weeks as tolerated to 1 mg/kg every other day. Cyclosporine was administered daily for patients with unrelated donors. For patients with related donors, cyclosporine was administered either every other day9 or daily, according to current practice.27 Doses of calcineurin inhibitor were adjusted as needed to avoid toxicity. In 26 cases, thalidomide was administered as part of the initial regimen for treatment of chronic GVHD.28

After resolution of chronic GVHD, immunosuppressive treatment was gradually withdrawn by tapering first the doses of prednisone and then the doses of calcineurin inhibitor as tolerated.9 Recurrent chronic GVHD was generally treated by increasing the dose of prednisone or cyclosporine. Other immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, sirolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, or tacrolimus (cyclosporine for patients who received tacrolimus) were administered as needed to treat steroid-refractory chronic GVHD. In some cases, agents used for treatment of steroid-refractory chronic GVHD were administered as part of a phase 2 study.

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed according to information available as of December 2002. Cumulative incidence estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) were computed according to methods described previously.29 Factors evaluated for association with outcome included age of the patient at time of transplantation, pretransplantation disease risk category, time from pretransplantation diagnosis to transplantation, donor/patient sex, donor parity, donor age, donor type (related or unrelated), graft-versus-host mismatching at individual HLA loci (A, B, C, DRB1, DQB1), number of mismatched HLA loci in the recipient, source of stem cells, year of transplantation, use of tacrolimus for GVHD prophylaxis, grade of acute GVHD, time from transplantation to diagnosis of chronic GVHD, type of onset, individual sites affected by chronic GVHD (skin, eyes, mouth, gastrointestinal tract, liver, lung, other), number of sites affected, dose of prednisone at the onset of chronic GVHD, total serum bilirubin concentration more than 2.0 mg/dL at the onset of chronic GVHD, and platelet count less than 100 000/μL at the onset of chronic GVHD. Factors having P less than .1 for association with outcome by univariate testing were added sequentially to a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model using a step-up procedure until the P value for the likelihood ratio test was more than .05. For the analysis of time to discontinuation of immunosuppressive treatment, follow-up was censored at death or the onset of recurrent malignancy, whichever occurred first. For the analysis of time to death not related to recurrent malignancy, follow-up was censored at the onset of recurrent malignancy. P values shown in the Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 are 2-sided and are not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Patient and transplant characteristics before onset of chronic GVHD in 751 patients

Characteristic . | . |

|---|---|

| Patient age, median (range), y | 39.5 (0.8-67.0) |

| Disease at transplantation, no. (%) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 118 (16) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 144 (19) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 303 (40) |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 95 (13) |

| Chronic lymphoid leukemia | 10 (1) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma or Hodgkin disease | 44 (6) |

| Multiple myeloma | 11 (1) |

| Other* | 26 (3) |

| Pretransplantation risk category, n (%)† | |

| Low | 54 (7) |

| Intermediate | 562 (75) |

| High | 135 (18) |

| Donor age, median (range), y | 39.3 (0.0-81.7) |

| Donor/recipient sex, no. (%) | |

| Male/male | 249 (33) |

| Male/female | 161 (21) |

| Female/male | 199 (26) |

| Female/female | 142 (19) |

| Donor type, no. (%) | |

| HLA-identical related | 329 (44) |

| HLA-mismatched related | 60 (8) |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 190 (25) |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated | 172 (23) |

| No. of mismatched HLA loci (%) | |

| 0 | 531 (71) |

| 1 | 130 (17) |

| 2 | 69 (9) |

| More than 2 | 16 (2) |

| Unknown‡ | 4 (0.5) |

| Conditioning regimen, no. (%) | |

| Cyclophosphamide and TBI | 424 (56) |

| Busulfan and cyclophosphamide | 245 (33) |

| Busulfan and TBI | 42 (6) |

| Other | 40 (5) |

| Source of stem cells, no. (%) | |

| Bone marrow | 600 (80) |

| Mobilized blood | 147 (20) |

| Cord blood | 4 (0.5) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, no. (%) | |

| Cyclosporine plus methotrexate | 637 (85) |

| Tacrolimus plus methotrexate | 24 (3) |

| Other | 90 (12) |

| Year of transplantation, no. (%) | |

| 1994-1997 | 424 (56) |

| 1998-2000 | 327 (44) |

| Prior acute GVHD, no. (%) | |

| Grade 0-I | 106 (14) |

| Grade II | 456 (61) |

| Grades III-IV | 189 (25) |

Characteristic . | . |

|---|---|

| Patient age, median (range), y | 39.5 (0.8-67.0) |

| Disease at transplantation, no. (%) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 118 (16) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 144 (19) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 303 (40) |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 95 (13) |

| Chronic lymphoid leukemia | 10 (1) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma or Hodgkin disease | 44 (6) |

| Multiple myeloma | 11 (1) |

| Other* | 26 (3) |

| Pretransplantation risk category, n (%)† | |

| Low | 54 (7) |

| Intermediate | 562 (75) |

| High | 135 (18) |

| Donor age, median (range), y | 39.3 (0.0-81.7) |

| Donor/recipient sex, no. (%) | |

| Male/male | 249 (33) |

| Male/female | 161 (21) |

| Female/male | 199 (26) |

| Female/female | 142 (19) |

| Donor type, no. (%) | |

| HLA-identical related | 329 (44) |

| HLA-mismatched related | 60 (8) |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 190 (25) |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated | 172 (23) |

| No. of mismatched HLA loci (%) | |

| 0 | 531 (71) |

| 1 | 130 (17) |

| 2 | 69 (9) |

| More than 2 | 16 (2) |

| Unknown‡ | 4 (0.5) |

| Conditioning regimen, no. (%) | |

| Cyclophosphamide and TBI | 424 (56) |

| Busulfan and cyclophosphamide | 245 (33) |

| Busulfan and TBI | 42 (6) |

| Other | 40 (5) |

| Source of stem cells, no. (%) | |

| Bone marrow | 600 (80) |

| Mobilized blood | 147 (20) |

| Cord blood | 4 (0.5) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, no. (%) | |

| Cyclosporine plus methotrexate | 637 (85) |

| Tacrolimus plus methotrexate | 24 (3) |

| Other | 90 (12) |

| Year of transplantation, no. (%) | |

| 1994-1997 | 424 (56) |

| 1998-2000 | 327 (44) |

| Prior acute GVHD, no. (%) | |

| Grade 0-I | 106 (14) |

| Grade II | 456 (61) |

| Grades III-IV | 189 (25) |

Twenty-three patients had nonmalignant diseases.

The low-risk category included chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase and aplastic anemia. The high-risk category included chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis, acute leukemia or lymphoma in relapse, refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation, and myeloma. The intermediate-risk category included all other diseases.

HLA-C and -DQ typing was not available for 3 cord blood donors. HLA-C typing was also not available for one marrow donor.

Patient characteristics at initial diagnosis of chronic GVHD

Characteristic . | . | No. unknown . |

|---|---|---|

| Months from transplantation to diagnosis, median (range) | 3.9 (2.2-28.2) | 0 |

| Type of onset, no. (%) | 45 | |

| De novo | 103 (15) | |

| Quiescent | 501 (71) | |

| Progressive | 102 (14) | |

| Sites involved, no. (%) | ||

| Skin | 566 (75) | 1 |

| Eyes | 185 (25) | 9 |

| Mouth | 378 (51) | 5 |

| Liver | 249 (33) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 340 (45) | 2 |

| Other* | 47 (6) | 1 |

| No. of sites involved (%) | 0 | |

| 1-2 | 432 (58) | |

| 3 | 246 (33) | |

| More than 3 | 73 (10) | |

| Dose of prednisone at diagnosis, mg/kg, no. (%) | 0 | |

| None | 280 (37) | |

| More than 0 but less than 0.5 | 220 (29) | |

| 0.5-1.0 | 155 (21) | |

| More than 1.0 | 96 (13) | |

| Platelet count less than 100 000/μL at diagnosis, no. (%) | 343 (46) | 2 |

| Serum bilirubin level more than 2 mg/dL at diagnosis, no. (%) | 121 (16) | 5 |

Characteristic . | . | No. unknown . |

|---|---|---|

| Months from transplantation to diagnosis, median (range) | 3.9 (2.2-28.2) | 0 |

| Type of onset, no. (%) | 45 | |

| De novo | 103 (15) | |

| Quiescent | 501 (71) | |

| Progressive | 102 (14) | |

| Sites involved, no. (%) | ||

| Skin | 566 (75) | 1 |

| Eyes | 185 (25) | 9 |

| Mouth | 378 (51) | 5 |

| Liver | 249 (33) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 340 (45) | 2 |

| Other* | 47 (6) | 1 |

| No. of sites involved (%) | 0 | |

| 1-2 | 432 (58) | |

| 3 | 246 (33) | |

| More than 3 | 73 (10) | |

| Dose of prednisone at diagnosis, mg/kg, no. (%) | 0 | |

| None | 280 (37) | |

| More than 0 but less than 0.5 | 220 (29) | |

| 0.5-1.0 | 155 (21) | |

| More than 1.0 | 96 (13) | |

| Platelet count less than 100 000/μL at diagnosis, no. (%) | 343 (46) | 2 |

| Serum bilirubin level more than 2 mg/dL at diagnosis, no. (%) | 121 (16) | 5 |

Lung (n = 27), female genital tract (n = 8), and muscle or fascia (n = 6) were the most frequently affected sites.

Multivariable model of time to discontinuation of immunosuppressive treatment*

Variable . | Hazard ratio†(95% CI) . | P‡ . |

|---|---|---|

| Mobilized blood versus marrow | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | < .0001 |

| Female donor for male recipient | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | .0001 |

| No. of sites involved, per site | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | .0002 |

| Serum bilirubin level more than 2 mg/dL at diagnosis | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | .02 |

| No. of mismatched HLA loci, per locus | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | .007 |

| Year of transplantation, per 5 y (1994-2000) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | .04 |

Variable . | Hazard ratio†(95% CI) . | P‡ . |

|---|---|---|

| Mobilized blood versus marrow | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | < .0001 |

| Female donor for male recipient | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | .0001 |

| No. of sites involved, per site | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | .0002 |

| Serum bilirubin level more than 2 mg/dL at diagnosis | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | .02 |

| No. of mismatched HLA loci, per locus | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | .007 |

| Year of transplantation, per 5 y (1994-2000) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | .04 |

Ten patients were not included in the model because of missing data.

Hazard ratios less than 1.0 indicate a lower rate of discontinued treatment, resulting in a prolonged duration of treatment in the presence of the indicated risk factor as compared to its absence. In this model, death and recurrent malignancy were treated as competing risks. Follow-up was censored for patients who died or had recurrent malignancy before immunosuppressive treatment was discontinued.

Likelihood ratio test.

Multivariable model of nonrelapse mortality*

Variable . | Hazard ratio†(95% CI) . | P‡ . |

|---|---|---|

| Prednisone dose per mg/kg | 2.6 (2.0-3.4) | < .0001 |

| Platelet count less than 100 000/μL at diagnosis | 2.2 (1.5-3.1) | < .0001 |

| Acute GVHD, versus 0-I | .002 | |

| Grade II | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | |

| Grades III-IV | 1.7 (0.9-3.1) | |

| Serum bilirubin level more than 2 mg/dL at diagnosis | 2.1 (1.4-2.9) | .0002 |

| Donor age per 10 y | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .009 |

| No. of HLA-mismatched loci per locus | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | .01 |

| Patient age per 10 y | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | .002 |

Variable . | Hazard ratio†(95% CI) . | P‡ . |

|---|---|---|

| Prednisone dose per mg/kg | 2.6 (2.0-3.4) | < .0001 |

| Platelet count less than 100 000/μL at diagnosis | 2.2 (1.5-3.1) | < .0001 |

| Acute GVHD, versus 0-I | .002 | |

| Grade II | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | |

| Grades III-IV | 1.7 (0.9-3.1) | |

| Serum bilirubin level more than 2 mg/dL at diagnosis | 2.1 (1.4-2.9) | .0002 |

| Donor age per 10 y | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .009 |

| No. of HLA-mismatched loci per locus | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | .01 |

| Patient age per 10 y | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | .002 |

Twelve patients were excluded from this model because of missing data.

In this model, recurrent malignancy was treated as a competing risk. Follow-up was censored for patients who had recurrent malignancy before death.

Likelihood ratio test.

Results

Patient and transplant characteristics

Between January 1994 and December 2000, 1840 patients received a myeloablative conditioning regimen followed by allogeneic HCT at our center, and 1401 (76%) survived for at least 100 days after the transplantation. Among these, 853 (61%) developed chronic GVHD requiring systemic immunosuppressive treatment. Four additional patients who died before day 100 were diagnosed with chronic GVHD. The research files for 751 of the 857 patients with chronic GVHD contained a signed consent form allowing the use of medical records for research purposes. Most of these 751 patients had hematologic malignancies (Table 1). Approximately half had unrelated donors.Approximately 30% of all patients had graft-versus-host antigen or allele mismatching at HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, or -DQB1. Nearly all patients received either cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation (TBI) or busulfan and cyclophosphamide as the pretransplantation preparative regimen, and 80% received marrow as the source of hematopoietic stem cells. Most patients received the combination of cyclosporine and methotrexate for prevention of acute GVHD. Approximately 60% had grade II acute GVHD, and approximately 25% had grades III to IV GVHD before the onset of chronic GVHD.

Chronic GVHD characteristics

The median interval from transplantation to the onset of chronic GVHD was 3.9 months, and the latest onset of chronic GVHD occurred at 28 months after the transplantation (Table 2). In approximately two thirds of patients, the onset of chronic GVHD was preceded by acute GVHD that had resolved (quiescent onset). The remaining patients were evenly divided with either no prior acute GVHD (de novo onset) or a progressive onset of chronic GVHD from unresolved acute GVHD. Skin was the site most frequently affected at the onset of chronic GVHD. In decreasing order of frequency, the mouth, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and eyes were also often affected. In approximately 60% of cases, chronic GVHD affected only 1 or 2 sites. In one third of the cases, the dose of prednisone at the onset of chronic GVHD was equal to or more than 0.5 mg/kg/d. At the onset of chronic GVHD, 37% of the patients were not being treated with prednisone. Nearly half of the patients had platelet counts less than 100 000/μL at the onset of chronic GVHD.

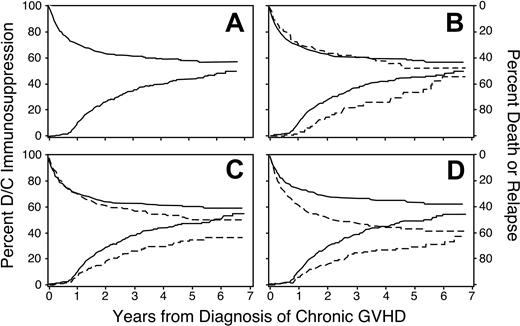

Discontinuation of immunosuppression

Across the 7-year follow-up in this study, the cumulative incidence of discontinued immunosuppressive treatment after resolution of chronic GVHD reached 50% (95% CI, 0.45-0.55; Figure 1A). The incidence of discontinued treatment first showed an appreciable increase at 9 months from the onset of chronic GVHD, coinciding with a complete medical re-evaluation in Seattle at the 1-year anniversary after the transplantation for many patients. Among the 274 patients who discontinued immunosuppression after resolution of chronic GVHD before recurrent malignancy or death, the median duration of treatment was 23 months. Across the entire 7-year follow-up period, the cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality during continued immunosuppression reached 24% (95% CI, 0.21-0.28), and the cumulative incidence of recurrent malignancy during continued immunosuppression reached 19% (95% CI, 0.16-0.22). From a separate analysis, the estimated proportion of patients alive without recurrent malignancy was 47%, and the proportion continuing immunosuppressive treatment was 7%. Hence, 15% of patients who were alive without recurrent malignancy at 7 years still required immunosuppressive treatment.

Discontinuation of immunosuppression. Time to discontinuation of immunosuppression is prolonged among patients who received mobilized peripheral blood (B), among male recipients with female donors (C), and among patients with HLA disparity (D). Panel A shows the cumulative incidence of discontinued immunosuppressive treatment without recurrent malignancy (lower curve and left-hand scale) and the competing risks of death or recurrent malignancy during continued immunosuppressive treatment (upper curve and right-hand scale) among all patients. Other panels show the same results for patients with (– – –) or without (—) the indicated risk factor. In panel C, results for female recipients with either male or female donors were similar to those for male recipients with male donors.

Discontinuation of immunosuppression. Time to discontinuation of immunosuppression is prolonged among patients who received mobilized peripheral blood (B), among male recipients with female donors (C), and among patients with HLA disparity (D). Panel A shows the cumulative incidence of discontinued immunosuppressive treatment without recurrent malignancy (lower curve and left-hand scale) and the competing risks of death or recurrent malignancy during continued immunosuppressive treatment (upper curve and right-hand scale) among all patients. Other panels show the same results for patients with (– – –) or without (—) the indicated risk factor. In panel C, results for female recipients with either male or female donors were similar to those for male recipients with male donors.

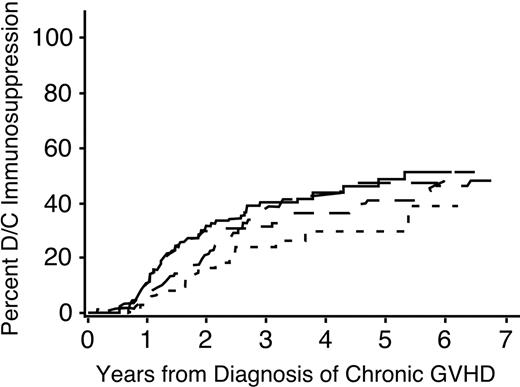

A multivariate analysis identified 6 factors associated with the duration of immunosuppressive treatment for chronic GVHD (Table 3). The duration was prolonged in patients who had received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–mobilized blood cells instead of marrow (Figure 1B), in male patients with female donors compared to other combinations (Figure 1C), in patients who had HLA disparity with their donors (Figure 1D), and in patients who had multiple sites affected by the disease (Figure 2). An elevated total serum bilirubin concentration at the onset of chronic GVHD was weakly associated with a longer duration of immunosuppressive treatment. For unclear reasons, chronic GVHD appeared to resolve more slowly among patients who underwent transplantation more recently as compared to those who had received transplants in earlier years, even after adjustment for use of mobilized blood cells as opposed to marrow.

Time to discontinuation of immunosuppression is prolonged among patients with more sites affected by chronic GVHD. ——, one site; — —, 2 sites; ––-–, 3 sites; –, more than 3 sites.

Time to discontinuation of immunosuppression is prolonged among patients with more sites affected by chronic GVHD. ——, one site; — —, 2 sites; ––-–, 3 sites; –, more than 3 sites.

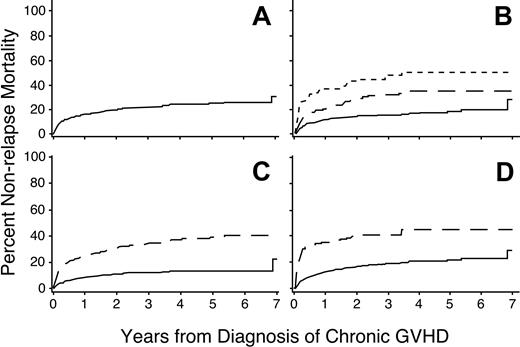

Nonrelapse mortality

Overall, the respective 1- and 3-year nonrelapse mortality rates were 16% (95% CI, 0.13-0.19) and 22% (95% CI, 0.19-0.25; Figure 3A). A multivariate analysis identified 7 factors associated with increased risks of nonrelapse mortality (Table 4). The dose of prednisone at the onset of chronic GVHD was the most significant risk factor (Figure 3B). Univariate analysis showed that progressive onset of chronic GVHD was associated with a higher risk of nonrelapse mortality, but this factor was no longer significant after accounting for the dose of prednisone at the onset of chronic GVHD. In keeping with previous studies,21-23,25,26 platelet counts less than 100 000/μL and serum total bilirubin concentrations more than 2 mg/dL were highly associated with increased risks of nonrelapse mortality (Figure 3C-D). Patients with histories of grades III to IV acute GVHD and those having HLA disparity with their donors had increased risks of nonrelapse mortality. Older age of both the patient and the donor were also independently associated with increased risks of nonrelapse mortality.

Risk factors for nonrelapse mortality. Higher doses of prednisone (B), platelet count less than 100 000/μL (C), or serum total bilirubin concentration more than 2.0 mg/dL (D) at the time of diagnosis are associated with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality among patients with chronic GVHD. Panel A shows the cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality among all patients. Panel B shows results for patients with prednisone doses less than 0.5 mg/kg body weight (——), 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg (— —), or more than 1.0 mg/kg (-–-). Other panels show results for patients with (– – –) or without (—) the indicated risk factor.

Risk factors for nonrelapse mortality. Higher doses of prednisone (B), platelet count less than 100 000/μL (C), or serum total bilirubin concentration more than 2.0 mg/dL (D) at the time of diagnosis are associated with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality among patients with chronic GVHD. Panel A shows the cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality among all patients. Panel B shows results for patients with prednisone doses less than 0.5 mg/kg body weight (——), 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg (— —), or more than 1.0 mg/kg (-–-). Other panels show results for patients with (– – –) or without (—) the indicated risk factor.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis showed similarities and differences in risk factors associated with prolonged treatment and those associated with nonrelapse mortality among patients with chronic GVHD. Recipient HLA disparity and hyperbilirubinemia at the onset of chronic GVHD were associated with both prolonged treatment and an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality. Transplantation of G-CSF–mobilized blood cells, the use of female donors for male recipients, and involvement of multiple sites were associated with prolonged treatment but not with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality. Thrombocytopenia and high-dose glucocorticoid treatment immediately before the onset of chronic GVHD, a prior history of acute GVHD, and older age of the patient or donor were associated with increased risks of nonrelapse mortality but not with the need for prolonged treatment of chronic GVHD.

A striking finding of the present study is that transplantation of mobilized blood cells as compared to marrow was associated with prolonged immunosuppressive treatment for chronic GVHD but not with increased nonrelapse mortality. These results are consistent with results from a randomized prospective trial comparing outcomes with blood cells versus marrow from HLA-identical sibling donors.30 The association between use of mobilized blood cells and prolonged treatment for chronic GVHD was also observed in the present study after patients who participated in the previous randomized trial were excluded from the analysis (data not shown). We speculate that the unexpectedly low mortality despite prolonged treatment might be related to higher CD4 T-cell counts and improved immune function among blood cell recipients as compared to marrow recipients with chronic GVHD.31 The inhibition of immune function by GVHD and immunosuppressive treatment might be outweighed by the higher numbers of CD4 T cells in blood cell recipients.

Several studies have shown a higher incidence of chronic GVHD among male recipients with female donors than with other recipient and donor combinations.14,16,19 Moreover, the risk of chronic GVHD increased according to parity of the donor, suggesting that chronic GVHD, like acute GVHD, might be related to alloimmunization of the donor.12,15,17,18 In the present study, we did not analyze donor parity as a risk factor because this information was not available for a large number of donors. With the higher incidence of chronic GVHD and the longer duration of immunosuppressive treatment needed to control chronic GVHD, the use of female donors for male recipients has been associated with slightly decreased survival after HCT in some studies.19 Taken together, these results suggest that, in general, male donors should be selected in preference to female donors whenever possible, except perhaps for male patients with a high risk of recurrent malignancy after the transplantation.

All of the patients included in our study were judged to have chronic GVHD requiring systemic immunosuppressive treatment. Previous studies have suggested that patients with “clinical limited” chronic GVHD involving only the eyes or mouth, or localized skin involvement, with or without liver involvement, have a low risk of mortality and do not need systemic immunosuppressive treatment.3,4 In current practice, however, we generally prescribe systemic immunosuppressive treatment for patients who have clinical limited chronic GVHD and glucocorticoid administration or thrombocytopenia at the onset of the disease, because these characteristics are associated with increased risks of nonrelapse mortality. Patients with fewer sites affected by chronic GVHD appear to have a favorable prognosis, as indicated by the shorter duration of treatment needed to control the disease.

The incidence of chronic GVHD after HCT is increased with the use of unrelated donors as compared to HLA-identical siblings.23 Our current results show increased treatment duration and nonrelapse mortality according to the number of mismatched HLA loci and emphasize the importance of avoiding HLA mismatches whenever possible. We found no evidence that treatment duration or nonrelapse mortality was affected by mismatching at any specific HLA locus. After accounting for HLA mismatching, we also found no evidence that treatment duration or nonrelapse mortality was affected by the use of unrelated donors as opposed to related donors.

Results of the multivariable model suggested that hyperbilirubinemia at the onset of chronic GVHD and transplantation during the past several years had some association with a need for prolonged immunosuppressive treatment. The P values for these associations were much higher than those for other risk factors included in the model, and these associations should be viewed with caution in light of the multiple comparisons made throughout this exploratory retrospective study. Hyperbilirubinemia at the onset of chronic GVHD was also associated with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality in previous studies.21,26 We have not identified any convincing explanation for the apparently prolonged treatment among patients diagnosed with chronic GVHD during more recent years. More frequent use of growth factor–mobilized blood cells for the transplant cannot explain this observation because the multivariate model includes this risk factor.

Our results did not confirm an association between prior grades III to IV acute GVHD and duration of immunosuppressive treatment as reported by Lee et al.26 Patients in the present study were older, had a higher incidence of prior acute GVHD, and had a higher incidence of skin and gastrointestinal involvement at the onset of chronic GVHD. Half the patients evaluated by Lee et al26 had clinical limited chronic GVHD, which might explain why the median duration of treatment was less than a year in their study, as compared to more than 2 years in our study.

Our analysis has reconfirmed the association between thrombocytopenia and increased risk of nonrelapse mortality among patients with chronic GVHD.22,23,25 Instead of including progressive onset as a risk factor for increased risk of nonrelapse mortality, the current model included grades III to IV acute GVHD and prednisone dose immediately before the onset of chronic GVHD. All patients who were treated with prednisone at doses more than 1 mg/kg had prior acute GVHD, and most of these patients had a progressive onset of chronic GVHD. Our current results indicate that quantitative information from the dose of prednisone may offer an advantage over qualitative information regarding the onset type in predicting nonrelapse mortality among patients with chronic GVHD. Other investigators have recently reported similar associations between prior acute GVHD and nonrelapse mortality among patients with chronic GVHD.26,32 In previous studies, rash involving more than 50% of the body surface at the onset of chronic GVHD has been associated with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality.24 We could not test this association in the present study because information regarding the extent of rash was not consistently available for patients who were diagnosed with chronic GVHD by the referring physician.

Our finding that older patients have increased nonrelapse mortality after the onset of chronic GVHD is entirely consistent with results of other studies.11-18,25 Older age of the donor has been associated with an increased risk of chronic GVHD13,17 and with an increased risk of mortality after unrelated HCT.17 These results, together with our finding that older donor age was associated with an increased risk of nonrelapse mortality after the onset of chronic GVHD, offer a compelling rationale for selecting younger donors in preference to older donors whenever possible.

Our results regarding risk factors associated with the duration of immunosuppressive treatment will require confirmation from other cohorts of patients with chronic GVHD. Separate studies will also be needed to evaluate outcomes after the use of nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens, because our current study was restricted to patients who received myeloablative conditioning regimens. We have not attempted to analyze outcomes after treatment with specific agents in this retrospective study because the number of patients treated initially with agents other than prednisone and cyclosporine was small. More importantly, the validity of any retrospective study attempting to evaluate specific agents for treatment of chronic GVHD would be highly questionable because of inability to control for selection biases.

Our results may provide physicians and patients with useful information regarding the duration of treatment to be expected when chronic GVHD is first diagnosed. Our finding that 15% of patients surviving without recurrent malignancy for more than 7 years require continued immunosuppressive treatment emphasizes the need for more effective methods of treatment for chronic GVHD. The identification of risk factors for duration of treatment and nonrelapse mortality may also assist the design of future prospective clinical trials to evaluate the use of interventions for treatment of chronic GVHD. We propose that time to discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy in the absence of recurrent malignancy could serve as a highly informative benchmark indicating induction of tolerance after successful treatment for chronic GVHD.9 For prospective studies, however, this end point would also have to include consideration of whether additional systemic immunosuppressive agents were administered before chronic GVHD resolved.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 3, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0200.

Supported by grants CA18029, HL36444, AI33484, and CA15704 from the US Public Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Judy Campbell, RN, for outstanding assistance in the management of patients with chronic GVHD; Mary Joy Lopez, Jane Jocum, and Chris Davis for assistance with data collection and data management; and Deborah Anderson for assistance with preparation of the figures. B.L.S. thanks Dwayne Mangum for many educational contributions.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal