Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) is a cytokine with multiple roles in the immune system, including the induction and potentiation of cellular functions in neutrophils (PMNs). TNF-α also induces apoptotic signals leading to the activation of several caspases, which are involved in different steps of the process of cell death. Inhibition of caspases usually increases cell survival. Here, we found that inhibition of caspases by the general caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk did not prevent TNF-α–induced PMN death. After 6 hours of incubation, TNF-α alone caused PMN death with characteristic apoptotic features (typical morphologic changes, DNA laddering, external phosphatidyl serine [PS] exposure in the plasma membrane, Bax clustering and translocation to the mitochondria, and degradation of mitochondria), which coincided with activation of caspase-8 and caspase-3. However, in the presence of TNF-α, PMNs died even when caspases were completely inhibited. This type of cell death lacked nuclear features of apoptosis (ie, no DNA laddering but aberrant hyperlobulated nuclei without typical chromatin condensation) and demonstrated no Bax redistribution, but it did show mitochondria clustering and plasma membrane PS exposure. In contrast, Fas-triggered PMN apoptosis was completely blocked by zVAD-fmk. Experiments with scavengers of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and with inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration, with PMN-derived cytoplasts (which lack mitochondria) and with PMNs from patients with chronic granulomatous disease (which have impaired nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate [NADPH] oxidase) indicated that TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced cell death depends on mitochondria-derived ROS. Thus, TNF-α can induce a “classical,” caspase-dependent and a “nonclassical” caspase-independent cell death.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) provides a wide variety of biologic signals, which are involved in the regulation of cell death and participate in the governing of immune homeostasis.1 TNF-α has been shown to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and sepsis.2-4 However, TNF-α is also able to exert anti-inflammatory effects.5,6 The antiphlogistic potential of this cytokine can be ascribed, at least partly, to its ability to accelerate the apoptosis of neutrophils (PMNs), which are major effector cells of inflammation. Apoptotic cell death constitutes a powerful way of curtailing PMN-mediated reactions, providing a safe clearance of these potentially toxic cells.7 Moreover, the uptake of apoptotic cells by resident macrophages has an immunosuppressive effect, which gives an additional beneficial contribution to the control of inflammatory reactions.8The proapoptotic effect of TNF-α on PMNs has been well documented,9-14 although opposite results have also been published.15,16 Probably, this controversy can be explained by the findings that the effect of TNF-α on PMN survival may depend on the concentration of the cytokine17 as well as on the duration of stimulation and the initial functional capacity of the PMNs before exposition to TNF-α.11

The mechanism of apoptosis induction by TNF-α is closely related to the cascade of apoptotic cysteine proteases known as caspases, which represent a group of enzymes responsible for initiation and execution of apoptosis.18,19 A death signal from the TNF-α receptor is transduced to an adapter protein, TNF-α receptor-associated death domain (TRADD), which uses the next adapter protein, Fas receptor-associated death domain (FADD), to organize the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC).20 DISC recruits and activates the upstream initiator caspase-8, providing therefore activation of downstream effector caspases and the final steps of the apoptotic program.20,21 Inhibition of caspases, for example, by certain peptide ketones, which mimic the active site of the enzyme,22 has been shown to dramatically increase cell survival in various cell types, including PMNs.13,14,23 24

In our study, investigating the effects of TNF-α on PMN survival, we faced an unexpected phenomenon. We confirmed a central role for caspases in TNF-α–mediated apoptosis of PMNs, but at the same time we found that inhibition of caspases did not rescue PMNs from death in the presence of TNF-α but instead enhanced an as yet unidentified form of PMN death. Our experiments indicate that in PMNs 2 death pathways are induced by TNF-α: one is the predominant “classical” caspase-dependent apoptosis, whereas the other is a “nonclassical” death route, which becomes apparent when caspases are fully inhibited and involves mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Materials and methods

PMN purification and culturing

Heparinized venous blood was collected from healthy volunteers and 3 patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) after obtaining informed consent, and PMNs were isolated as described.25Briefly, 20 mL blood was diluted with 20 mL 10% trisodium citrate/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mononuclear cells and platelets were removed by density gradient centrifugation over isotonic Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) with a specific gravity of 1.076 g/mL. Erythrocytes were lysed by short treatment of the pellet fraction with an ice-cold isotonic NH4Cl solution (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], pH 7.4). The remaining PMNs were washed once in PBS and used for further manipulations. In all cases cell purity was more than 97%. PMNs were resuspended at a final concentration of 2 × 106/mL in Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium (BioWhittaker, Brussels, Belgium) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom), penicillin 100 IU/mL (Yamanouchi, Tokyo, Japan), streptomycin 100 μg/mL (Gibco BRL), and glutamine 300 μg/mL. One milliliter of cell suspension was put in each well of 24-well plates (NUNC Brand Products, Roskilde, Denmark) and was incubated for 6 hours in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. PMNs were cultured with 20 ng/mL TNF-α (Calbiochem, Bad Soden, Germany), with 150 μM z-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone (zVAD-fmk;, Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA), with 5 mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC; Sigma, St Louis, MO) or with indicated combinations. Normal PMNs were also incubated with 500 ng/mL mouse anti-Fas (CD95) monoclonal antibodies (Abs; clone CH11; Immunotech, Marseille, France), with 10 mM 4,5-dihydroxy-1,3-benzene disulfonic acid (tiron; Sigma), with 100 μM rotenone (Sigma), with 2 mM sodium azide (Calbiochem), with 300 μM thenoyltrifluoroacetone (TTFA; Sigma) alone or in a combination with zVAD-fmk or TNF-α/zVAD-fmk, where indicated. When the combinations of reagents were used, they were added in culture medium simultaneously. The incubation time and the concentrations were found to be optimal in preliminary experiments (data not shown). Control PMNs were cultured without additions (no stimulus). Because of longer transportation time, CGD neutrophils as well the healthy day-control cells were purified and cultured in a “delayed” manner (delayed cultures), ie, 4 to 5 hours after collection of the blood sample.

Cytoplast preparation and culturing

PMNs were isolated from the buffy coat of 500 mL fresh blood from volunteer donors, as described in “PMN purification and culturing.” Cytoplasts were prepared from 108PMNs as described previously.26 Briefly, PMNs were centrifuged through a discontinuous Ficoll-70 (Sigma) gradient (12.5%, 16%, 25%) prewarmed to 37°C, containing 5 μg/mL cytochalasin B (Sigma). Centrifugation was performed for 30 minutes at 34°C in a model L2-65B ultracentrifuge with an AH-629 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) at 81 000g. After centrifugation, the top band of cellular material was collected. This band was composed of more than 99% of cytoplasts, as assessed by light microscopy of cytospins stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa solution. Cytoplasts were recognized by their absence of a nucleus. Following several washings in PBS, cytoplasts were resuspended at a final concentration of 8 × 106 per mL in the culture medium and were incubated overnight (16 hours) under conditions indicated in Figure 7. This duration of culture induced maximal differences in cytoplast apoptosis between tested conditions (data not shown).

Measurement of cell death

After 6 hours of incubation, PMNs were split into 2 portions, which were washed once in ice-cold PBS. One portion was stained with the annexin-V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis assay kit (Bender MedSystems, Vienna, Austria) and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter scan (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) as described previously.24 Dead cells were defined as positive for annexin-V–FITC or for annexin-V–FITC/PI staining. Cell death was expressed as a percentage of dead cells in relation to the total number of counted cells. The number of cells recovered after culture was similar under all conditions tested and was close to 90% of the initial input of cells. Another portion of PMNs (2-3 × 105 cells) was used for preparation of cytospins stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa solution. The cytospins were estimated by light microscopy for morphologic changes in PMNs (described in “Results”). A minimum of 300 cells was scored for each sample, and the percentages of dead PMNs were determined. Cytoplast death was assessed by annexin-V–FITC binding as described earlier, without the PI step, with 4 × 105 cytoplasts for each preparation. Annexin-V+ cytoplasts were considered to be dead.

Western blotting

The cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 was determined by Western blotting. Whole cell lysates were obtained by boiling 0.5 × 106 PMNs in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer with 2% mercaptoethanol for 5 minutes. Proteins were resolved on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis (PAGE) and were electrotransferred to Immun-Blot polyvinylidene diflouride (PVDF) membrane (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The blots were sequentially probed with monoclonal mouse antihuman–caspase-8 Abs (clone 1C12; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), which recognize full-length caspase-8 as well as its fragments; with polyclonal rabbit antihuman–caspase-3 Abs (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), which recognize both inactive procaspase-3 and its cleavage product; and with polyclonal rabbit antihuman-Bax Abs (Pharmingen). All indicated Abs were used at a final dilution of 1:1000. After exposure to each primary Ab, the blots were incubated with appropriate secondary Abs conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham, Arlington Height, IL) at a final dilution of 1:2500, followed by band visualization with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit as described by the manufacturer (Amersham). This reprobing was successful because of a different exposition time required for visualization of the proteins of interest. For caspase-8–related bands it was approximately 30 minutes, for caspase-3 and its cleavage product 5 minutes, and for Bax protein less than 1 minute.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA

DNA was extracted from 5 × 106 freshly isolated PMNs or from PMNs treated under conditions indicated in Figure 3 by a PureGene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Isolated DNA was electrophoresed in a 1.2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, and the gels were photographed under ultraviolet light.

Assessment of p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in PMNs and cytoplasts

After purification, PMNs and cytoplasts were resuspended in culture medium at final concentrations of 2 × 106/mL and 8 × 106/mL, respectively, and were incubated without or with 20 ng/mL TNF-α for 10 minutes in a water-bath at 37°C. Thereafter, whole cell lysates were prepared, and Western blotting was performed as described earlier with 1 × 106 cytoplast or 0.5 × 106 PMN equivalents per lane. The blots were probed with phosphospecific polyclonal rabbit Abs against human p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase (Cell Signaling Technology), which selectively recognize phosphorylated p38. To determine protein loading, reprobe was performed with polyclonal rabbit Abs against total p38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), which bind to p38 irrespectively of its phosphorylation state.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)

For the mitochondrial staining, MitoTracker GreenFM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used. To estimate mitochondrial morphology, unfixed PMNs were stained with 100 μM MitoTracker GreenFM and were analyzed by a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany) as described.24 To obtain simultaneous staining of mitochondria and Bax protein, PMNs were stained with 1 mM MitoTracker GreenFM. Thereafter, the cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in staining buffer containing 0.1% saponin (wt/vol; Calbiochem) and 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (Sigma), and were labeled by polyclonal rabbit antihuman-Bax Abs (final dilution 1:250; Pharmingen) followed by secondary staining with AlexaFluor-568–conjugated goat antirabbit immunoglobulin G (Molecular Probes) at a final concentration of 2.5 μg/mL as has been previously described.24 After staining, at least 300 PMNs were counted in each sample, and the percentages of cells with prevailing morphology (images shown in Figures 4-5) were determined, as indicated in the legends of Figures 4-5.

Statistics

Where applicable, values were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni posttest using GraphPad Prism version 3.0 software. Differences were accepted as significant atP < .05.

Results

TNF-α alone induces classical apoptosis in PMNs

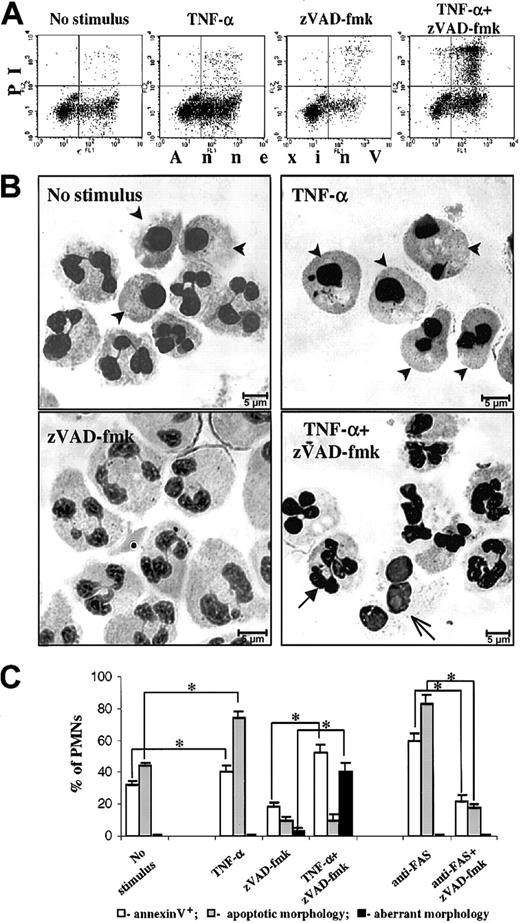

Already after 6 hours of culture, untreated PMNs underwent spontaneous apoptosis, with 31.9% ± 2.5% of the cells being annexin-V+ (Figure 1A, No stimulus). Typical apoptotic morphology, including rounding of nuclei, pronounced chromatin condensation, and cell shrinkage, was displayed by 34.2% ± 2.0% of untreated PMNs (Figure 1B, top left; apoptotic cells shown by arrowheads). After 6 hours of treatment with TNF-α, the fraction of annexin-V+ PMNs slightly but significantly increased to 40.0% ± 4.3% (Figure 1A, TNF-α). When scored by morphologic changes, the proportion of PMNs with classical apoptotic features amounted to 74.0% ± 4.3% in the presence of TNF-α (Figure 1B, top right). These data are consistent with previous observations that at early time points TNF-α is indeed able to induce apoptosis in PMNs.11,13 14

Death of PMNs.

(A-B) PMNs were cultured for 6 hours without additions, with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk, or with the combination of these agents, and cell death was assessed (A) by FACScan analysis of annexin-V–FITC/PI staining and (B) by morphologic examination of cytospins stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (for quantitative data see C). Arrowheads indicate PMNs that have undergone spontaneous or TNF-α–induced apoptosis with typical apoptotic morphology; closed and open arrows depict PMNs with aberrant morphology appeared after TNF-α/zVAD-fmk treatment (see “Results” for details). (C) Quantitative data obtained by FACScan analysis and cytospin evaluation of PMNs treated for 6 hours under the conditions as indicated. Dosage of additions: TNF-α and zVAD-fmk, as indicated for A and B; anti-Fas monoclonal Abs, 500 ng/mL. *P < .05. Data represent means ± SEM of 4 to 8 separate experiments performed in duplicate.

Death of PMNs.

(A-B) PMNs were cultured for 6 hours without additions, with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk, or with the combination of these agents, and cell death was assessed (A) by FACScan analysis of annexin-V–FITC/PI staining and (B) by morphologic examination of cytospins stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (for quantitative data see C). Arrowheads indicate PMNs that have undergone spontaneous or TNF-α–induced apoptosis with typical apoptotic morphology; closed and open arrows depict PMNs with aberrant morphology appeared after TNF-α/zVAD-fmk treatment (see “Results” for details). (C) Quantitative data obtained by FACScan analysis and cytospin evaluation of PMNs treated for 6 hours under the conditions as indicated. Dosage of additions: TNF-α and zVAD-fmk, as indicated for A and B; anti-Fas monoclonal Abs, 500 ng/mL. *P < .05. Data represent means ± SEM of 4 to 8 separate experiments performed in duplicate.

Inhibition of caspases in the presence of TNF-α leads PMNs to an aberrant death different from apoptosis

We subsequently studied the activation of initiator caspase-8 and executioner caspase-3 in PMNs by Western blotting. In freshly isolated PMNs caspase-8 was present as a 57- to 55-kd precursor protein (Figure2A, lane 1), and caspase-3 appeared as a 32-kd proenzyme (Figure 2B, lane 1). These bands represent the full-length procaspases.13,27 PMNs that had undergone spontaneous apoptosis on culturing without stimuli displayed the initial activation of caspase-8 with the appearance of the large cleavage fragment of 43 to 41 kd (Figure 2A, lane 2). Caspase-3 was partially cleaved into the 17-kd fragment (Figure 2B, lane 2). Stimulation with TNF-α caused a more pronounced activation of caspase-8 and caspase-3. The 57- to 55-kd procaspase-8 was completely degraded into smaller fragments, including the active 18-kd fragment28 (Figure 2A, lane 4), and the 32-kd procaspase-3 was entirely processed to the active 17-kd product (Figure 2B, lane 4).

Cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 in PMNs.

Whole-cell lysates from freshly isolated PMNs (lane 1), from PMNs cultured for 6 hours without additions (lane 2), with 150 μM zVAD-fmk (lane 3), with 20 ng/mL TNF-α (lane 4), or with the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk combination (lane 5) were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Western blot was performed with anti–caspase-8 monoclonal Abs (A). Then the blot was reprobed with anti–caspase-3 polyclonal Abs (B). The expression of Bax protein determined by anti-Bax polyclonal Abs was used as a measurement for equal protein loading (C). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Cleavage of caspase-8 and caspase-3 in PMNs.

Whole-cell lysates from freshly isolated PMNs (lane 1), from PMNs cultured for 6 hours without additions (lane 2), with 150 μM zVAD-fmk (lane 3), with 20 ng/mL TNF-α (lane 4), or with the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk combination (lane 5) were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Western blot was performed with anti–caspase-8 monoclonal Abs (A). Then the blot was reprobed with anti–caspase-3 polyclonal Abs (B). The expression of Bax protein determined by anti-Bax polyclonal Abs was used as a measurement for equal protein loading (C). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Next, we checked whether inhibition of caspases could abrogate the proapoptotic effects of TNF-α. For this purpose the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk was used. When used alone, this agent significantly reduced apoptotic membrane changes (18.6% ± 2.0% annexin-V+ PMNs; Figure 1A, zVAD-fmk) as well as morphologic features of apoptosis (9.4% ± 2.5% cells with apoptotic morphology; Figure 1B, bottom left), when compared with untreated PMNs (Figure 1A-B, No stimulus). Moreover, zVAD-fmk completely inhibited activation of caspase-8 (Figure 2A, lane 3) and caspase-3 (Figure 2B, lane 3), because no cleavage products were detectable, and the enzymes were only present as full-length precursors in the lysates from zVAD-fmk–treated PMNs.

Unexpectedly, addition of zVAD-fmk to TNF-α did not rescue PMNs from death. Instead, after such treatment, 52.4% ± 4.7% of the PMNs became annexin-V+, as shown in Figure 1A (TNF-α + zVAD-fmk plot). These PMNs had an aberrant appearance (Figure 1B, bottom right): some cells (open arrow) were enlarged, with expanded disintegrated chromatin and visible vacuolization, whereas others (closed arrow) had hyperlobulated nuclei with moderately condensed chromatin (this picture is different from classical apoptotic features shown in Figure 1B, top left and top right). The proportion of such unusual cells in the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk preparation was 40.0% ± 6.2%, whereas typical apoptotic morphology was noted in 9.4% ± 4.3% of the PMNs treated with this combination. The latter value is similar to the level of morphologic apoptosis found when PMNs were treated with zVAD-fmk alone, as summarized in Figure 1C. Notably, the fraction of aberrant cells was negligible among untreated or TNF-α–treated PMNs and very low in the presence of zVAD-fmk alone (< 3%). Of importance, the aberrant death of PMNs induced by TNF-α/zVAD-fmk proceeded despite the absence of any detectable activation of caspase-8 (Figure 2A, lane 5) or caspase-3 (Figure 2B, lane 5). The equivalence of protein loading was established by Bax protein expression (Figure 2C), which has been previously shown to be stable in PMNs by us24 and various other groups.29-31

To investigate the role of protein synthesis in the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk death pathway, PMNs were also tested in the presence of cycloheximide. However, transcription blockade showed no effect on TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced cytotoxicity in PMNs (data not shown).

Taken together, these results indicate that TNF-α can induce 2 different death signals in PMNs, one caspase dependent and another caspase independent.

No DNA laddering in TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–treated PMNs

To further characterize the caspase-independent cell death in PMNs, we investigated DNA laddering. Internucleosomal DNA degradation is a hallmark of apoptosis.32 Indeed, DNA from PMNs that had been incubated with TNF-α for 6 hours demonstrated a typical laddering pattern, indicating internucleosomal cleavage characteristic for apoptosis (Figure 3). In contrast, the electrophoretic pattern of DNA extracted from TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–treated PMNs was similar to that of fresh, untreated, or zVAD-fmk–treated cells, cultured for 6 hours (Figure 3). Thus, also in this respect, TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced PMN death appeared to be different from typical apoptosis.

DNA laddering in PMNs.

DNA extracted from freshly isolated PMNs as well as from PMNs cultured for 6 hours without additions, with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk or with the combination of these agents, was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and internucleosomal fragmentation (DNA laddering) was assessed. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

DNA laddering in PMNs.

DNA extracted from freshly isolated PMNs as well as from PMNs cultured for 6 hours without additions, with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk or with the combination of these agents, was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and internucleosomal fragmentation (DNA laddering) was assessed. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

zVAD-fmk prevents Fas-receptor–induced apoptosis in PMNs

The Fas/Apo-1/CD95 system shares common death signaling pathways with the TNF-α–receptor. Both receptors belong to the TNF/nerve growth factor receptor family33 and can recruit the same adapter protein, FADD, forming the DISC to mediate death signals to the caspase cascade.20,21 As shown in Figure1C, ligation of the Fas-receptor with agonistic anti-Fas monoclonal Abs CH-1123 34 led PMNs after a 6-hour culture to pronounced apoptosis, with 59.9% ± 4.7% of annexin-V+ cells and 83.3% ± 5.2% of cells with a typical apoptotic morphology (compare with Figure 1C, No stimulus). However, induction of apoptosis by anti-Fas monoclonal Abs was almost completely prevented by zVAD-fmk (Figure 1C; 21.9% ± 3.8% annexin-V+ and 17.5% ± 2.7% morphologically apoptotic PMNs; compare with Figure1C, zVAD-fmk alone). Thus, despite the fact that Fas and TNF-α–receptors engage common upstream death pathways, Fas receptor-mediated death signals are strictly caspase dependent and can be blocked by a caspase inhibitor, whereas TNF-α has the potential to bypass the caspase cascade, causing atypical death in PMNs in the presence of zVAD-fmk.

TNF-α/zVAD-fmk treatment causes in PMNs degradation of the mitochondria without Bax redistribution

Our recent study has shown that PMNs contain mitochondria, which play an important role in the apoptotic program of these cells.24 To check whether the mitochondria are involved in caspase-independent death pathway, we undertook the next set of experiments. Specific mitochondrial fluorescent staining revealed that most of the untreated and zVAD-fmk–treated PMNs (Figure4, top left and bottom left, respectively) after 6 hours of incubation preserved a tubular structure of the mitochondria, as was observed in fresh cells.24When TNF-α alone was present in the culture medium, the mitochondria changed into large unstructured aggregates (Figure 4, top right) typical for apoptosis.24 Interestingly, the proportion of cells with clustered mitochondria closely correlated with the proportion of cells with an apoptotic morphology (data not presented), indicating that changes in the mitochondrial structure form an early and reliable marker of apoptosis. The TNF-α/zVAD-fmk combination also altered the appearance of the mitochondria (Figure 4, bottom right), leading to clustering and degradation of these organelles, although these mitochondrial aggregates were smaller in comparison to the aggregates in PMNs treated with TNF-α alone.

Staining patterns of mitochondria in PMNs.

PMNs were incubated for 6 hours without additions (No stimulus), with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk, or with the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk combination. Then the cells were stained with MitoTracker GreenFM and analyzed with CLSM. Each image represents the following proportion of the total cell population (mean ± SEM): 73.8% ± 8.9% in No stimulus; 66.7% ± 5.4% in TNF-α; 89.0% ± 4.3% in zVAD-fmk; 77.0% ± 3.6% in TNF-α/zVAD-fmk. Bar is 5 μm. Results are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

Staining patterns of mitochondria in PMNs.

PMNs were incubated for 6 hours without additions (No stimulus), with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk, or with the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk combination. Then the cells were stained with MitoTracker GreenFM and analyzed with CLSM. Each image represents the following proportion of the total cell population (mean ± SEM): 73.8% ± 8.9% in No stimulus; 66.7% ± 5.4% in TNF-α; 89.0% ± 4.3% in zVAD-fmk; 77.0% ± 3.6% in TNF-α/zVAD-fmk. Bar is 5 μm. Results are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

When PMNs were costained for mitochondria and Bax protein, most of the untreated cells showed after the 6-hour incubation a punctate localization of Bax, remaining separate from mitochondria (Figure5, top panel), as was also observed in fresh PMNs.24 In PMNs after 6 hours of culture in the presence of zVAD-fmk, Bax protein maintained a staining pattern similar to fresh and to untreated cultured cells, visible as a punctate distribution separate from mitochondria (data not shown). In contrast, treatment with TNF-α caused redistribution of Bax into large clusters, which colocalized with mitochondria (Figure 5, middle panel; a shift in fluorescence to yellow depicts colocalization). In TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–treated PMNs, Bax remained punctate and hardly colocalized with the mitochondria (Figure 5, bottom panels).

Subcellular redistribution of Bax protein in PMNs.

PMNs were cultured for 6 hours without additions (No stimulus), with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, or with a combination of 20 ng/mL TNF-α and 150 μM zVAD-fmk. Then the cells were stained with MitoTracker GreenFM, fixed, permeabilized, stained with polyclonal Abs specific for Bax, and analyzed with CLSM. (Because of the fixation and permeabilization procedures, the mitochondrial staining [green] showed a more diffuse cytoplasmic pattern than the tubular structures shown in Figure 4, left panels). Each image represents the following proportion of the total cell population (mean ± SEM): 77.7% ± 5.4% in No stimulus; 63.3% ± 8.8% in TNF-α; 88.3% ± 5.7% in TNF-α/zVAD-fmk. Bar is 5 μm. This figure is representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

Subcellular redistribution of Bax protein in PMNs.

PMNs were cultured for 6 hours without additions (No stimulus), with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, or with a combination of 20 ng/mL TNF-α and 150 μM zVAD-fmk. Then the cells were stained with MitoTracker GreenFM, fixed, permeabilized, stained with polyclonal Abs specific for Bax, and analyzed with CLSM. (Because of the fixation and permeabilization procedures, the mitochondrial staining [green] showed a more diffuse cytoplasmic pattern than the tubular structures shown in Figure 4, left panels). Each image represents the following proportion of the total cell population (mean ± SEM): 77.7% ± 5.4% in No stimulus; 63.3% ± 8.8% in TNF-α; 88.3% ± 5.7% in TNF-α/zVAD-fmk. Bar is 5 μm. This figure is representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that TNF-α can act via a classical apoptotic route, inducing subcellular Bax redistribution and its aggregation with mitochondria, which have been shown to be significant events during the execution of apoptosis in various cell types,35-38 including PMNs.24 At the same time, TNF-α stimulation under conditions that preclude caspase activation does not lead to Bax changes, but it does cause degradation of mitochondria. Again, this finding may indicate the presence of a caspase-independent, mitochondria-dependent route of cell death in PMNs that is different from apoptosis.

PMN-derived cytoplasts lacking mitochondria do not display TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced death phenomenon

To further elucidate the role of mitochondria in TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced death, we used PMN-derived cytoplasts, which are cellular vesicles from which mitochondria have been eliminated.24,39 First, we determined whether the TNF-α receptors were functional on the cytoplast surface. As a read-out, the TNF-α receptor-mediated phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase was used.40 Figure 6 (top panel) demonstrates that TNF-α induced phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase both in cytoplasts and PMNs. Next, cytoplasts were cultured under various conditions. Untreated and TNF-α–treated cytoplasts after culture exposed phosphatidyl serine on the outer layer of the plasma membrane, which was evident by annexin-V positivity of 54.2% ± 4.9% and 50.3% ± 5.7% cytoplasts, respectively (Figure 7, top left and top right plots, respectively). zVAD-fmk reduced the number of annexin-V+cytoplasts to 7.2% ± 1.9% (Figure 7, bottom left plot). Similar values were found in the experiments with PMNs (Figure 1C). However, in contrast to PMNs, cytoplasts treated with a combination TNF-α/VAD-fmk remained “alive,” with only 11.0% ± 1.3% annexin-V+ cells (Figure 7, bottom right plot). Thus, addition of TNF-α to zVAD-fmk had no effect on cytoplast survival. This finding indicates that TNF-α was not able to induce a caspase-independent death in cytoplasts in the absence of the mitochondria, despite the intact receptor signaling, and the caspase inhibitor completely preserved its prosurvival effect. Also, this finding demonstrates that the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk combination itself is not nonspecifically toxic for the cells.

p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in cytoplasts.

Freshly isolated cytoplasts or fresh PMNs were treated for 10 minutes with control medium or with 20 ng/mL TNF-α. Thereafter, whole cell lysates were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Western blot was performed with monoclonal Abs that specifically recognized the phosphorylated form of p38 (top panel). Reprobing with anti–total p38 monoclonal Abs (bottom panel), which recognizes p38 regardless of its phosphorylation state, gives an estimation of the equal protein loading. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments.

p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in cytoplasts.

Freshly isolated cytoplasts or fresh PMNs were treated for 10 minutes with control medium or with 20 ng/mL TNF-α. Thereafter, whole cell lysates were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Western blot was performed with monoclonal Abs that specifically recognized the phosphorylated form of p38 (top panel). Reprobing with anti–total p38 monoclonal Abs (bottom panel), which recognizes p38 regardless of its phosphorylation state, gives an estimation of the equal protein loading. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Death of cytoplasts.

Cytoplasts cultured overnight without additions or with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk, or with the combination of these agents were stained with annexin-V–FITC and were analyzed by FACScan. Cytoplasts with annexin-V staining were counted as dead cytoplasts (bottom right quadrant of each plot). *P < .05 versus No stimulus and TNF-α. Values represent means ± SEM of 5 separate experiments performed in duplicate.

Death of cytoplasts.

Cytoplasts cultured overnight without additions or with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk, or with the combination of these agents were stained with annexin-V–FITC and were analyzed by FACScan. Cytoplasts with annexin-V staining were counted as dead cytoplasts (bottom right quadrant of each plot). *P < .05 versus No stimulus and TNF-α. Values represent means ± SEM of 5 separate experiments performed in duplicate.

NADPH oxidase system-independent ROS are involved in the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced cytotoxic effects

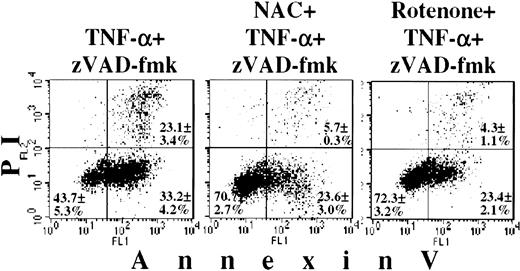

The data shown earlier indicated that the mitochondria may participate in the process of unusual TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced PMN death. How do these organelles contribute to this death pathway? One possibility is ROS production by the mitochondria in response to TNF-α stimulation, which mediates, at least in part, cytotoxic effects of this cytokine.41-43 NAC, a well-characterized ROS scavenger,34,44,45 had no effect on spontaneous apoptosis of PMNs, reduced TNF-α–induced apoptosis, and almost completely abrogated the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk death effects (Figure8 and data not shown). NAC significantly (P < .05) reduced the number of annexin-V+PMNs in TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–treated PMNs and completely prevented the appearance of morphologically aberrant cells (not shown). The ROS scavenger tiron,43 which is unrelated to NAC, also prevented TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced cell death (data not shown). The mitochondrial origin of ROS was further supported by experiments, in which we used inhibitors of the mitochondrial electron transport (respiratory) chain, ie, inhibitors of the mitochondrial ROS production.41 Rotenone stopped the death-inducing effects of the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk combination, preventing plasma membrane flip-flop (Figure 8; P < .05) and aberrant morphologic changes in the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–treated PMNs (data not shown). Two other mitochondrial inhibitors, sodium azide and TTFA, demonstrated a similar effect of rescuing PMNs from TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–mediated cell death (data not shown). Importantly, these mitochondrial inhibitors, when added alone, influenced neither the basal level of PMN apoptosis nor PMN adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels, measured by a luciferase-based assay46 (not shown). The latter result can be explained by the fact that PMNs mainly use glycolysis rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation for their energy supply.47

Effect of NAC and rotenone on TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced PMN cell death.

PMNs were cultured for 6 hours with a combination of 20 ng/mL TNF-α and 150 μM zVAD-fmk or with TNF-α/zVAD-fmk in combination with 5 mM NAC or 100 μM rotenone. Afterwards, PMNs were stained with annexin-V/PI and analyzed by FACScan. Values represent the percentage of cells (mean ± SEM) for each respective quadrant. Data obtained in 5 independent experiments.

Effect of NAC and rotenone on TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced PMN cell death.

PMNs were cultured for 6 hours with a combination of 20 ng/mL TNF-α and 150 μM zVAD-fmk or with TNF-α/zVAD-fmk in combination with 5 mM NAC or 100 μM rotenone. Afterwards, PMNs were stained with annexin-V/PI and analyzed by FACScan. Values represent the percentage of cells (mean ± SEM) for each respective quadrant. Data obtained in 5 independent experiments.

The most powerful source of ROS in PMNs is the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase system, which provides a rapid and a dramatic increase in ROS generation known as the respiratory burst. To check whether ROS produced by NADPH oxidase participates in the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–mediated cell death, we investigated PMNs from 3 patients with CGD. Because of a genetic defect in the NADPH oxidase in PMNs from these patients, their cells cannot generate ROS.48 In our experiments, PMNs from patients with CGD displayed a behavior in terms of the death rate similar to the normal cells under the conditions tested as illustrated by annexin-V/PI staining in Table 1. CGD PMNs had levels of spontaneous apoptosis comparable to the healthy day-control cells incubated in the delayed cultures (see “Materials and methods”). zVAD-fmk protected CGD cells from apoptosis as it did in healthy PMNs, and the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk combination induced a similar amount of phosphatidyl serine exposure and aberrant morphology in CGD PMNs, as was observed in normal PMNs (Table 1 and data not shown). Hence, the NADPH oxidase system plays no role in the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced death of PMNs. Interestingly, the ROS scavenger NAC also rescued CGD PMNs from the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced death by preventing the membrane changes (Table 1) and the appearance of unusual morphology (not shown), indicating that CGD PMNs have the ability to produce some ROS from an alternative source.

TNF-α/zVAD-fmk-induced cell death of CGD PMNs

| Treatment . | % Annexin-V+ PMNs . | |

|---|---|---|

| CGD, n = 3 . | Control, n = 3 . | |

| No addition* | 50.2 ± 5.1 | 46.4 ± 3.2 |

| TNF-α | 53.0 ± 4.5 | 59.0 ± 11.0 |

| zVAD-fmk | 35.0 ± 4.3† | 31.2 ± 10.5† |

| TNF-α/zVAD-fmk* | 63.7 ± 12.7‡ | 65.8 ± 9.5‡ |

| NAC + TNF-α/zVAD-fmk | 35.2 ± 1.81-153 | 35.3 ± 3.21-153 |

| Treatment . | % Annexin-V+ PMNs . | |

|---|---|---|

| CGD, n = 3 . | Control, n = 3 . | |

| No addition* | 50.2 ± 5.1 | 46.4 ± 3.2 |

| TNF-α | 53.0 ± 4.5 | 59.0 ± 11.0 |

| zVAD-fmk | 35.0 ± 4.3† | 31.2 ± 10.5† |

| TNF-α/zVAD-fmk* | 63.7 ± 12.7‡ | 65.8 ± 9.5‡ |

| NAC + TNF-α/zVAD-fmk | 35.2 ± 1.81-153 | 35.3 ± 3.21-153 |

PMNs isolated from 3 CGD patients and healthy day controls were incubated for 6 hours (“delayed” culturing; see “Material and methods”) without additions, with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, with 150 μM zVAD-fmk, with the combination of these agents alone, or with addition of 5 mM NAC. Thereafter, PMNs were stained with annexin-V/PI and analyzed by FACScan. Values represent means ± SD of 3 to 5 separate experiments performed in duplicate.

n = 5.

P < .05 versus No addition.

P < .05 versus zVAD-fmk.

P < .05 versus TNF-α/zVAD-fmk, in the respective columns for CGD or control cells.

Discussion

Most forms of programmed cell death proceed through the activation of caspases, which can be blocked by the general caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk. In this study we describe an as yet unidentified form of PMN death induced by TNF-α in the presence of caspase inhibition. TNF-α alone induced activation of the classical apoptotic route in PMNs, which is accompanied by activation of initiator and executioner caspases, Bax translocation to mitochondria, mitochondrial clustering, internucleosomal cleavage of DNA, and typical apoptotic changes in morphology and plasma membranes. When caspase activity was blocked, TNF-α–treated PMNs displayed no Bax redistribution and no DNA fragmentation, and increased cell death as indicated by the plasma membrane exposure of phosphatidyl serine in the outer layer (flip-flop). Moreover, these PMNs showed an aberrant morphology, with hyperlobulated nuclei and expanded, disintegrated chromatin. Apparently, under conditions when caspases do not function, an alternative, TNF-α-induced nonclassical, caspase-independent pathway of cell death is revealed in PMNs.

Further experiments demonstrated the involvement of ROS in the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced cytotoxicity (Figure 8), independent of protein synthesis. During the last decade, the physiologic role of ROS has been gradually reevaluated. These agents moved from a category of merely unwanted side products of oxidative metabolism to a cohort of important messenger molecules.49-51 Intracellular sources of ROS are mainly represented by electron-transfer processes in mitochondria49,52 and enzymatic oxidation provided by various oxidases.50 Among oxidases, the NADPH oxidase system is one of the most powerful generators of ROS, being used by PMNs for the killing of ingested microorganisms.48 We found that PMNs from patients with CGD, who have an impaired NADPH oxidase system, died in the same caspase-independent way after TNF-α/zVAD-fmk treatment as did healthy PMNs. This observation ruled out the involvement of NADPH oxidase-derived ROS in this nonclassical form of PMN death. Experiments with PMN-derived cytoplasts underscored that these ROS originated from mitochondria, because cytoplasts, having no mitochondria, did not show any enhanced exposure of phosphatidyl serine after TNF-α/zVAD-fmk stimulation, in contrast to intact PMNs. A number of inhibitors of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, including rotenone, sodium azide, and TTFA, were also able to prevent the TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced features of cell death, again pointing to the mitochondria as the main origin of ROS production. These findings are in line with previous reports on the cytotoxic effects of TNF-α in cell lines,41-43 caused by ROS from mitochondria. Excessive amounts of ROS may cause direct oxidative damage of nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids53 or may make proteins more susceptible to proteolysis.54,55 Probably, such events take place during TNF-α/zVAD-fmk–induced PMN death, resulting in the observed cellular changes that could be prevented by ROS inhibitors. Importantly, mitochondria are not only a source of ROS but also a target for ROS.52 ROS produced in mitochondria may lead to self-damage of these organelles, causing apoptosis or necrosis.53 This could be an explanation for our data, which showed Bax-independent mitochondrial changes in PMNs after TNF-α/zVAD-fmk treatment. Undoubtedly, ROS production requires a tight control, and our results suggest that caspases might be involved in this regulation.44,56 Possibly, mitochondrial proteins involved in electron transport within these organelles and providing the excess production of oxygen radicals could be a direct substrate for caspases, because mitochondrial caspases with as yet unidentified intramitochondrial functions have been described.57Deactivation of this system by caspases could normally prevent the accumulation of ROS. Alternatively, caspases may play a role in the elimination of damaged lipids and proteins, which accumulate after TNF-α stimulation and may normally act as a natural sink for ROS.56

Several studies have shown that blockade of caspases in some cell linessensitize them to TNF-α–mediated cytotoxicity.44,56,58 The researchers refer to this type of cell death as necrosis,56 “a nonapoptotic” cell death,44 or “a transitional stage between apoptosis and necrosis.”58 Such descriptions underline the complicated nature of the phenomenon but, at the same time, dictate the necessity to use an adequate set of tools for the registration of cell death. For example, staining with propidium iodide alone56 does not seem to be sufficient to discriminate between necrotic and apoptotic cell death, because these basically different types of death both lead to the final disruption of the plasma membrane.59 The death rate of PMNs treated with a combination of TNF-α and caspase inhibitors has obviously been underestimated,13 14 because only a DNA fragmentation assay has been used as a read-out for cell death, whereas our present findings clearly show the absence of this hallmark of apoptosis under these conditions.

We conclude from our data that TNF-α is able to trigger 2 pathways of cell death in PMNs, and the availability of downstream caspases appears to determine the mode of cell death. In the presence of an intact caspase cascade TNF-α mainly induces the classical form of apoptosis. However, when caspase activity is blocked, eg, by zVAD-fmk, other signals result from TNF-α stimulation. This nonclassical and caspase-independent pathway of PMN death, which lacks most of the characteristic apoptotic features, is mediated by mitochondria-derived ROS. In PMNs, this signaling pathway seems to be restricted to the TNF-α receptor, because the Fas receptor-mediated as well as the spontaneous apoptosis in PMNs were both completely blocked by zVAD-fmk.

Our present data raise another issue. Caspases are attractive targets for pharmacologic intervention in vivo in disease states that have been associated with enhanced apoptosis.60,61 Caspase inhibitors, predominantly zVAD-fmk–like active-site mimetic peptide ketones, have been extensively used in animal models of human diseases. These inhibitors have shown beneficial effects in various types of ischemia-reperfusion injury,62-64 but also in infectious conditions, including bacterial meningitis and sepsis.65,66 The promising approach of using caspase inhibitors as anti-inflammatory agents should, however, be considered with caution because of the possible adverse effects.61For example, during ischemia-reperfusion injury and particularly during generalized infections, inflammation proceeds through a massive activation of PMNs and generation of inflammatory cytokines. Under many generalized inflammatory conditions, TNF-α–induced apoptosis of PMNs through the activation of caspases provides a “silent turnover” of these potentially hazardous cells and leads to a suppression of inflammation,8 limiting the extent of inflammatory reactions. Instead, inhibition of caspases may lead to a deterioration of the injury, caused by an as yet unforeseen atypical neutrophil death as shown in our study, with a potentially uncontrolled release of their contents, in contrast to the classical apoptotic cells. Moreover, under the circumstances of caspase inhibition, PMN cell death is exaggerated, and clearance mechanisms may be insufficiently able to minimize PMN-related damage. To date, the existence per se of caspase-independent cell death has been shown for several untransformed cell types, including T lymphocytes,67,68neurons,69-71 erythropoietic cells,72 and fibroblasts.73 Many researchers refrain to designate this type of cell turnover as “apoptosis,” because of a lack of some typical apoptotic features. Our data on PMNs support this view. The biologic significance and physiologic role as well as the precise mechanisms of this phenomenon warrant further study.

We are grateful to Dr P. Hordijk for his comments while preparing the manuscript, to Dr R. S. Weening for his help in obtaining blood from CGD patients, and to Dr S. Albracht for his gift of mitochondrial inhibitors.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 10, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0522.

Supported by a grant from Nuffic (N.A.M.). T.W.K. is a research fellow of the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Taco Kuijpers, Central Laboratory of the Netherlands Blood Transfusion Service (CLB), Department of Experimental Immunohematology, Plesmanlaan 125, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: t_kuijpers@clb.nl.

![Fig. 5. Subcellular redistribution of Bax protein in PMNs. / PMNs were cultured for 6 hours without additions (No stimulus), with 20 ng/mL TNF-α, or with a combination of 20 ng/mL TNF-α and 150 μM zVAD-fmk. Then the cells were stained with MitoTracker GreenFM, fixed, permeabilized, stained with polyclonal Abs specific for Bax, and analyzed with CLSM. (Because of the fixation and permeabilization procedures, the mitochondrial staining [green] showed a more diffuse cytoplasmic pattern than the tubular structures shown in Figure 4, left panels). Each image represents the following proportion of the total cell population (mean ± SEM): 77.7% ± 5.4% in No stimulus; 63.3% ± 8.8% in TNF-α; 88.3% ± 5.7% in TNF-α/zVAD-fmk. Bar is 5 μm. This figure is representative of at least 4 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/5/10.1182_blood-2002-02-0522/3/m_h80533874005.jpeg?Expires=1767698758&Signature=Kwl7xWoLbybQelCehBy3c1iI7FkI7lNJ5n2m8b-IQ7XkyZTHqoXw1sQ~4mqWsBEOqpokAuN1ZOOi4Eq2gmBSUdnEVQjoxIfvr7lCgRHKHR8OPapYgvY~skHBKcdS0u~RArvZ8-T229~6L0IS6M1p6~BGQS0nXpiZt0mhCSYKnDeT90bjleMOr~6WCijsn4VppMc8aFBAuXXho99Dp0BGa4UwvTyYdh77BNKVKCsaM9tz0YOYGUCXyX7F-B5RjhNeKd~QlHMRgqfWCQVZVtV3YpduEfVO9iBVnp7x3e7vMYozu7w2Pw5ixHUJneo~LGVd2qwqnEzsztWzBwFP8Uk~dA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal