Abstract

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a chronic lymphoproliferative disease, the cause of which is unknown. Diagnostic of HCL is abnormal expression of the gene that encodes the β2 integrin CD11c. In order to determine the cause of CD11c gene expression in HCL theCD11c gene promoter was characterized. Transfection of theCD11c promoter linked to a luciferase reporter gene indicated that it is sufficient to direct expression in hairy cells. Mutation analysis demonstrated that of predominant importance to the activity of the CD11c promoter is its interaction with the activator protein-1 (AP-1) family of transcription factors. Comparison of nuclear extracts prepared from hairy cells with those prepared from other cell types indicated that hairy cells exhibit abnormal constitutive expression of an AP-1 complex containing JunD. Functional inhibition of AP-1 expressed by hairy cells reducedCD11c promoter activity by 80%. Inhibition of Ras, which represents an upstream activator of AP-1, also significantly inhibited the CD11c promoter. Furthermore, in the hairy cell line EH, inhibition of Ras signaling through mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal–regulated kinase kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1/2) reduced not only CD11c promoter activity but also reduced both CD11c surface expression and proliferation. Expression in nonhairy cells of a dominant-positive Ras mutant activated the CD11cpromoter to levels equivalent to those in hairy cells. Together, these data indicate that the abnormal expression of the CD11cgene characteristic of HCL is dependent upon activation of the proto-oncogenes ras and junD.

Introduction

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) or leukemic reticuloendotheliosis represents approximately 2% of adult leukemias and is characterized by pancytopenia, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, leukocytosis, and neoplastic mononuclear cells in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, liver, and spleen.1 The name of the disease is derived from the presence of broad-based undulating ruffles on the surface of the leukemic cells that appear under the phase contrast microscope as cytoplasmic projections or “hairs.” These cells can be derived both from B and T lymphocytes as demonstrated by their expression of B- or T-cell–specific antigens and are characterized biochemically by their abnormal expression of the integrin heterodimer CD11c/CD18.2-4 Under normal circumstances the gene encoding the CD18 component of this marker is transcribed both in lymphocytes and myeloid cells, whereas the gene encoding the CD11c component is transcribed primarily in cells of the myeloid lineage.5 The CD11c/CD18 heterodimer is, therefore, normally largely restricted in its expression to the surface of myeloid cells dictated by the myeloid-specific transcription of theCD11c gene. In hairy cell leukemia the CD11c/CD18 heterodimer is present on not only myeloid cells but also on the neoplastic lymphocytes. Diagnostic of this disease is, therefore, the abnormal regulation of CD11c gene transcription. Consequently, elucidation of the molecular causes of this abnormal regulation are likely to result in insights into the molecular basis of hairy cell leukemia. Using this rationale we isolated the humanCD11c gene and identified the cis-acting elements that control its transcription. The most important of these elements interacts with activator protein-1 (AP-1) encoded by thejun and fos families of proto-oncogenes. In hairy cells an AP-1 complex containing JunD exhibits a constitutive pattern of expression, whereas in other cell types it is functionally expressed only upon induction with phorbol ester. The use of dominant-negative mutants in transfection assays demonstrated that both AP-1 and its upstream activator Ras are necessary for CD11cexpression in hairy cells. In addition, exogenous expression of a dominant-positive mutant of Ras was able to activate theCD11c promoter in nonhairy cells to a level equivalent to that seen in hairy cells. Taken together, these results indicate that activation of the proto-oncogenes junD and rasunderlie the abnormal expression of the CD11c gene characteristic of HCL.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The cell lines HeLa, IM-9, Mo, and U937 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and grown according to their specifications. The promegakaryocytic cell line MEG-016 was kindly provided by Dr W. S. May (John Hopkins Oncology Center, Baltimore, MD) through permission of Dr H. Saito (Nagoya University School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan). MEG-01 were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with glutamine, 20% fetal calf serum (FCS), aqueous penicillin G (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (50 μg/mL). The pre-erythroid/premegakaryocytic cell line K562 was kindly provided by Dr K. Bridges (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA), and Jurkat T-lymphocytic cells were kindly provided by Dr T. Wileman (AFRC Pirbright Laboratory, Pirbright, England). These cell lines were grown under the same conditions as the MEG-01 cells except that the medium was supplemented with 10% FCS. The hairy cell lines EH and HK7 were kindly provided by Dr G. B. Faguet (Veterans Administration Medical Center, Augusta, GA) and grown in α–minimum essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 15% FCS, 0.055 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and the antibiotics listed for the MEG-01 cell line. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was obtained from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO) and used at a concentration of 100 ng/mL where indicated. U0126 was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA) and used at a concentration of 8 μM. U0126 is an inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal–regulated kinase kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1/2).

Plasmid construction

The activity of the CD11c promoter was assessed using the expression vector pATLuc,8 which contains a promoterless firefly luciferase reporter gene. Initially, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to generate 2 fragments of the CD11c gene representing nucleotides − 128 to + 36 and − 117 to + 36 relative to the transcription initiation site.9 These fragments were then subcloned into the “filled-in” HindIII site of pATLuc to generate, respectively, p11Wt and p11ΔA. A mutant oligonucleotide was used in a PCR reaction to generate a fragment spanning nucleotides − 128 to + 36 where nucleotides − 112 to − 105 were substituted with the sequence 5′-GCCAAGCT-3′. This fragment was then subcloned into the “filled-in” HindIII site of pATLuc to generate p11ΔB. The construct p11ΔC was produced by subcloning PCR-generatedCD11c gene fragments representing nucleotides − 128 to − 92 and − 83 to + 36 into, respectively, the PstI andHindIII sites of pATLuc treated with T4 polymerase in the presence of deoxynucleotides. The p11ΔC construct, therefore, represents the effective substitution of nucleotides − 91 to − 84 with the mutant sequence 5′-GCCAAGCT-3′, the same mutant sequence as used in the generation of p11ΔB. The expression constructs p11ΔD to p11ΔH were produced in a similar manner as p11ΔC resulting in the effective mutation of, respectively, nucleotides − 72 to − 65, − 61 to − 54, − 39 to − 32, − 7 to + 1, and + 18 to + 25. The transfection control plasmid pRSV-β was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). The expression constructs pCMV and pTAM67 were kindly provided by Dr Michael J. Birrer (National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD), the mutant expression constructs pRasN17 and pRasV12 were kindly provided by Dr John M. Kyriakis (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), and the expression construct RSV-hjD was kindly provided by Dr Yosef Shaul (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel).

Transfection

Cells were transfected10-12 with 24 μgluciferase test plasmid together with 1 μg pRSV-β, which contains the lacZ gene. Each transfection of p11Wt and p11ΔA to p11ΔH was performed in parallel with a transfection of the negative control plasmid pATLuc. At 16 hours after electroporation, cells were processed for assay of β-galactosidase and luciferase activity. Transfections that used the effector plasmids RSV-hjD, pTAM67, pRasN17, or pRasV12 were performed as described above except that 8 μg luciferase plasmids were mixed with 16 μg effector plasmid and 1μg pRSV-β. As controls for these experiments, parallel transfections were performed with the empty parental vectors from which the effector plasmids were derived.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described by Farokhzad et al.12 DNA probes were generated by annealing complementary oligonucleotides that had been radiolabeled at their 5′ ends using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ32P] adenosine triphosphate. Nuclear extract (1.3 μg) was incubated at 4°C for 15 minutes in 70 mM KCl, 5 mM NaCl, 20 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane–HCl (pH 7.5), 0.5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2.4 μg poly d(I:C).poly d(I:C), and a 500 molar excess of unlabeled competitor probe where indicated. Radiolabeled probe (10 000 cpm, 0.05-0.15 ng) was then added and the incubation continued for 30 minutes prior to native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography. Electrophoretic mobility supershift assays were performed in the same way as the standard EMSA analyses except that, prior to the addition of DNA probes, nuclear extracts were preincubated for 15 minutes at 4°C with either 1 μL rabbit preimmune serum or 1 μL rabbit polyclonal antibody. All antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The double-stranded oligonucleotides used in analysis of the nuclear proteins that interact with the CD11c promoter were as follows: CD11c Box E, 5′-CCCCTCTGACTCATGCTGA-3′ and 3′-GGGGAGACTGAGTACGACT-5′; Consensus AP-1,5′-CTAGTGATGAGTCAGCCGGATC-3′ and 3′-GATCACTACTCAGTCGGCCTAG-5′ (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, CA); andConsensus Sp1, 5′-GATCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGATC-3′ and 3′-CTAGCTAGCCCCGCCCCGCTAG-5′ (Stratagene Cloning Systems).

Flow cytometric analysis

Flow cytometry was performed by incubating 5 × 105 cells with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated monoclonal antibody to CD11c (Accurate Chemical & Scientific, Westbury, NY) or immunoglobulin G1 FITC (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). After staining, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Results

The wild-type CD11c promoter directs expression in hairy cells

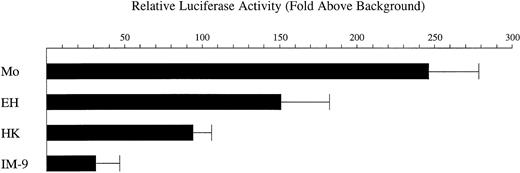

We have previously isolated the human CD11c gene and determined the nucleotide sequence of the 5′-flanking region (C.S.S., E.P.B., O.C.F., M.A.A., GenBank accession no.L19440). A fragment of the CD11c gene representing nucleotides − 128 to + 36 relative to the major transcription initiation site was cloned immediately upstream of aluciferase reporter gene to generate the construct p11Wt. Transfection experiments using this construct indicated that it was able to direct expression that was induced during activation of the monocytic cell line U937 and the T-lymphocytic cell line Jurkat (C.S.S., unpublished observations, October 1993). In order to establish whether p11Wt was able to direct expression in hairy cells it was transfected into the hairy cell lines Mo, EH, and HK (Figure1). These cell lines were established from different patients with hairy cell leukemia. Mo cells are derived from T cells, whereas EH and HK cells are derived from B cells.7,13 14 Transfection analysis demonstrated that in Mo, EH, and HK cells p11Wt is able to direct expression levels that averaged, respectively, 246-, 151-, and 94-fold above the background level conferred by the negative control plasmid pATLuc. In the B-lymphocytic cell line IM-9, which is not of hairy cell origin, p11Wt directed expression that averaged 31-fold above background.

The proximal promoter region of the CD11cgene drives transcription in hairy cells.

The expression construct p11Wt containing nucleotides − 128 to + 36 of the CD11c gene promoter was transfected into the cell lines Mo, EH, HK, and IM-9. Transfected cells were then left untreated for 16 hours prior to harvesting. The level of luciferasereporter gene activity, corrected for transfection efficiency, is expressed relative to that conferred by the negative control plasmid pATLuc. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments.

The proximal promoter region of the CD11cgene drives transcription in hairy cells.

The expression construct p11Wt containing nucleotides − 128 to + 36 of the CD11c gene promoter was transfected into the cell lines Mo, EH, HK, and IM-9. Transfected cells were then left untreated for 16 hours prior to harvesting. The level of luciferasereporter gene activity, corrected for transfection efficiency, is expressed relative to that conferred by the negative control plasmid pATLuc. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments.

A potential AP-1 binding site is critical for CD11cpromoter activity in both hairy and nonhairy cells treated with PMA

Taken together, our transfection data indicate that theCD11c promoter spanning nucleotides − 128 to + 36 contains the cis-acting elements sufficient to direct expression in hairy cells (Figure 1). Within the − 128/+ 36 region, 8 putative cis-acting elements were identified. These elements are herein referred to as Boxes A to H (Figure2). Box A binds the transcription factors PyRo1, Sp1, and Sp3.15-18 Box B binds Sp1, Sp3, and Purα.15-17,19 Box C contains a consensus recognition site for the Ets family of transcription factors and overlaps a site demonstrated to bind c-Myb.20,21 The c-Myb binding site overlapping Box C also represents a potential binding site for the basic helix-loop-helix group of transcription factors.22 Box D binds Sp1, Sp3, and Purα.15-17,19 Box E contains an AP-1 binding site and includes the sequence CTGAC, which, with its repeat, starting 6 nucleotides downstream, may represent a retinoic acid response element.23-26 Box F binds Purα and Ets transcription factors,19,27 and Box G binds the Ets factors PU.1 and GABPβ2.28 The sequence of Box G also resembles the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase group of “initiator” elements.29,30 Box H contains a consensus recognition site for the Ets family, overlaps consensus binding sites for C/EBP and c-Myb, and contains part of the sequence TTCCTGCAA representing a possible GAS element, which could mediate the induction of gene expression by both type I and type II interferons.31-33

Nucleotide sequence of the promoter region of theCD11c gene.

Numbering is relative to the major site of transcription initiation, which is indicated by a bent arrow.9 Boxed are thecis-acting control elements that were assessed for their functional importance by deletion and mutation analysis (Figure 3).

Nucleotide sequence of the promoter region of theCD11c gene.

Numbering is relative to the major site of transcription initiation, which is indicated by a bent arrow.9 Boxed are thecis-acting control elements that were assessed for their functional importance by deletion and mutation analysis (Figure 3).

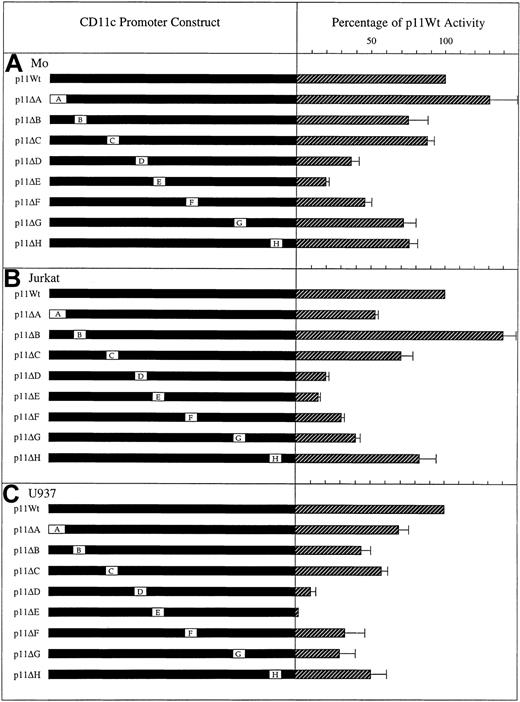

In order to determine the relevance of Boxes A to H to the transcriptional activity of the CD11c gene in hairy cells, linker scanning was used to test the effect of their specific mutation. This mutational analysis (Figure 3A) demonstrated that, with the exception of Box A and Box C, all the putative control elements identified by sequence analysis make significant contributions to promoter activity in PMA-treated Mo hairy cells. However, particularly important is Box E, representing a potential site of interaction with AP-1. Disruption of this element results in an 80% reduction in expression. In addition to being the most important element directing expression in PMA-treated hairy cells, Box E also represents the element most critical to PMA-induced expression of the CD11c promoter in Jurkat lymphocytic cells and U937 monocytic cells (Figure 3B-C).

Mutation analysis of the CD11c gene promoter.

Contribution of Boxes A to H to CD11c promoter activity in (A) PMA-treated Mo hairy cells, (B) PMA-treated Jurkat T-lymphocytic cells, and (C) PMA-treated U937 monocytic cells. The portions of theCD11c gene used in transfection assays are illustrated on the left as filled bars, and the regions either deleted (Box A) or mutated (Boxes B to H) are represented by open boxes. The wild-typeCD11c promoter spanning nucleotides − 128 to + 36 is present in the luciferase expression construct p11Wt, whereas p11ΔA to ΔH represent the specific replacement of Boxes A to H, respectively, with the pATLuc polylinker sequence 5′-GCCAAGCT-3′. Expressed as hatched bars on the right are the levels ofluciferase gene activity corrected for transfection efficiency and after subtraction of the background activity conferred by the control plasmid pATLuc. The level of expression of p11Wt is assigned a value of 100%, and the expression level conferred by the deletion and mutation constructs is displayed as a proportion of this value. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent transfection experiments.

Mutation analysis of the CD11c gene promoter.

Contribution of Boxes A to H to CD11c promoter activity in (A) PMA-treated Mo hairy cells, (B) PMA-treated Jurkat T-lymphocytic cells, and (C) PMA-treated U937 monocytic cells. The portions of theCD11c gene used in transfection assays are illustrated on the left as filled bars, and the regions either deleted (Box A) or mutated (Boxes B to H) are represented by open boxes. The wild-typeCD11c promoter spanning nucleotides − 128 to + 36 is present in the luciferase expression construct p11Wt, whereas p11ΔA to ΔH represent the specific replacement of Boxes A to H, respectively, with the pATLuc polylinker sequence 5′-GCCAAGCT-3′. Expressed as hatched bars on the right are the levels ofluciferase gene activity corrected for transfection efficiency and after subtraction of the background activity conferred by the control plasmid pATLuc. The level of expression of p11Wt is assigned a value of 100%, and the expression level conferred by the deletion and mutation constructs is displayed as a proportion of this value. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent transfection experiments.

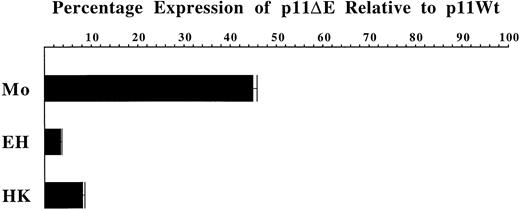

The potential AP-1 site is critical to CD11c promoter activity in untreated hairy cells

Box E is clearly vital to the activity of theCD11c promoter in PMA-treated hairy and nonhairy cells. However, given that Box E represents a putative AP-1 binding site and the normal pattern of AP-1 expression is induction with PMA, the importance of Box E to CD11c promoter activity in PMA-treated cells is unsurprising. Therefore, we tested the importance of Box E to CD11c promoter activity in hairy cells untreated with PMA. The Box E mutant p11ΔE was transfected into the hairy cell lines Mo, EH, and HK untreated with PMA in parallel with the wild-typeCD11c promoter construct p11Wt (Figure4). After correction for transfection efficiency these experiments demonstrated that the mutant promoter exhibits expression levels that are 55%, 96%, and 92% reduced compared with wild-type in Mo, EH, and HK, respectively. Consequently, Box E appears critical to the constitutive activity of theCD11c promoter in untreated hairy cells.

Contribution of Box E to the activity of theCD11c promoter in untreated hairy cells.

The luciferase reporter construct p11Wt, containing the wild-type CD11c promoter, was transfected in parallel with the Box E mutant p11ΔE into Mo, EH, and HK hairy cells. After correction for transfection efficiency, the level of expression of p11Wt is assigned a value of 100%, and the expression level conferred by p11ΔE is displayed as a proportion of this value. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent transfection experiments.

Contribution of Box E to the activity of theCD11c promoter in untreated hairy cells.

The luciferase reporter construct p11Wt, containing the wild-type CD11c promoter, was transfected in parallel with the Box E mutant p11ΔE into Mo, EH, and HK hairy cells. After correction for transfection efficiency, the level of expression of p11Wt is assigned a value of 100%, and the expression level conferred by p11ΔE is displayed as a proportion of this value. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent transfection experiments.

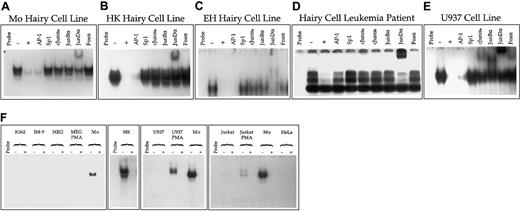

Hairy cells exhibit abnormal expression of an AP-1 complex containing JunD

The inappropriate expression of the CD11c gene in HCL can be due to 2 occurrences. The first is a mutation in or near the gene itself, and the second is abnormal regulation of the control factors with which the gene interacts. The activity in hairy cells of the wild-type CD11c promoter suggests the latter possibility. To further investigate this possibility, we performed EMSA analysis of the putative control factors expressed in hairy cells that interact with Box E, the most important of the functional cis-acting elements within the CD11cpromoter. These analyses indicated that in both hairy cell lines and hairy cells isolated directly from a patient, Box E interacts specifically with a DNA binding activity that is immunologically indistinguishable from AP-1 (Figure 5, upper panel). However, the AP-1 complex expressed in hairy cells differs from that expressed in nonhairy cells in 2 important respects. First, in hairy cells AP-1 is expressed constitutively, whereas in other cell types it is expressed only after induction with phorbol ester (Figure 5, lower panel). Second, the AP-1 complex expressed in hairy cells interacts only with an antibody directed against the product of the proto-oncogene junD, whereas in nonhairy cells the AP-1 complex expressed upon phorbol ester treatment is composed of a mixture of JunD, c-Jun, JunB, and members of the Fos family (Figure 5, upper panel).

AP-1 expression in hairy and nonhairy cells.

(A-E) Analysis of AP-1 interaction with Box E in hairy and nonhairy cells. The radiolabeled DNA fragment CD11c Box E containing Box E (Figure 2) was incubated with no nuclear extract (Probe) or 1.3 μg of nuclear extract prepared from the hairy cell lines Mo (A); HK (B); or EH (C); the neoplastic lymphocytes of a patient with HCL (D); or U937 cells treated for 24 hours with PMA (E). Binding reactions were performed in the absence (−) or presence (+) of a 500-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe or double-stranded DNA fragments purchased from Stratagene Cloning Systems that represent consensus binding sites for AP-1 and Sp1. DNA-protein binding reactions were also performed with no competitor after rabbit polyclonal antibodies that specifically interact with c-Jun (cJunαa, cJunαb), JunB (JunBα), JunD (JunDα) or the Fos family (Fosα) were incubated with nuclear extracts. (F) Cellular distribution of AP-1 interaction with Box E. EMSA was performed using the radiolabeled DNA fragment CD11c Box E incubated with no nuclear extract (Probe) or 1.3 μg of nuclear extract prepared from MEG-01 cells induced for 24 hours with PMA; MEG-01 cells untreated with PMA; Mo hairy cells; HK hairy cells; U937 cells induced for 24 hours with PMA; U937 cells untreated with PMA; Jurkat cells induced for 24 hours with PMA; Jurkat cells untreated with PMA; K562; HeLa; or IM-9 cells. Binding reactions were performed either in the absence (−) of unlabeled specific competitor DNA or in the presence (+) of a 500-fold molar excess of unlabeled CD11c Box E.

AP-1 expression in hairy and nonhairy cells.

(A-E) Analysis of AP-1 interaction with Box E in hairy and nonhairy cells. The radiolabeled DNA fragment CD11c Box E containing Box E (Figure 2) was incubated with no nuclear extract (Probe) or 1.3 μg of nuclear extract prepared from the hairy cell lines Mo (A); HK (B); or EH (C); the neoplastic lymphocytes of a patient with HCL (D); or U937 cells treated for 24 hours with PMA (E). Binding reactions were performed in the absence (−) or presence (+) of a 500-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe or double-stranded DNA fragments purchased from Stratagene Cloning Systems that represent consensus binding sites for AP-1 and Sp1. DNA-protein binding reactions were also performed with no competitor after rabbit polyclonal antibodies that specifically interact with c-Jun (cJunαa, cJunαb), JunB (JunBα), JunD (JunDα) or the Fos family (Fosα) were incubated with nuclear extracts. (F) Cellular distribution of AP-1 interaction with Box E. EMSA was performed using the radiolabeled DNA fragment CD11c Box E incubated with no nuclear extract (Probe) or 1.3 μg of nuclear extract prepared from MEG-01 cells induced for 24 hours with PMA; MEG-01 cells untreated with PMA; Mo hairy cells; HK hairy cells; U937 cells induced for 24 hours with PMA; U937 cells untreated with PMA; Jurkat cells induced for 24 hours with PMA; Jurkat cells untreated with PMA; K562; HeLa; or IM-9 cells. Binding reactions were performed either in the absence (−) of unlabeled specific competitor DNA or in the presence (+) of a 500-fold molar excess of unlabeled CD11c Box E.

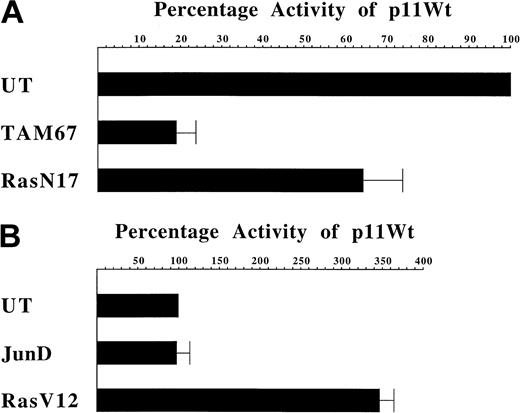

AP-1 expression is necessary for CD11c promoter activity in hairy cells, but expression of JunD is insufficient to activate the CD11c promoter in nonhairy cells

Our observation that hairy cells exhibit abnormal chronic expression of AP-1 suggests that this may be responsible for their support of CD11c promoter activity. If this hypothesis is correct then inhibition of AP-1 would be expected to inhibit the activity of the CD11c promoter. TAM67 is a cDNA that encodes a c-Jun protein lacking a transactivation domain.34 The TAM67 protein forms heterodimers with wild-type AP-1 proteins to form transactivation-deficient AP-1 complexes. TAM67 expression, therefore, exhibits a dominant-negative effect on AP-1 function. This dominant-negative mutant has been used previously in vitro to inhibit AP-1 activity.34 35 In order to assess the affect of transientTAM67 expression on the activity of the CD11cpromoter in hairy cells, this mutant was transfected into the Mo hairy cell line in combination with either pATLuc or p11Wt (Figure6A). Under these conditions, the level of luciferase activity directed by p11Wt reached, on average, 37 times that conferred by pATLuc. In contrast, in the presence of the plasmid vector empty of the TAM67 mutant, p11Wt produced levels of activity that were, on average, 200-fold above the level directed by pATLuc. Consequently, TAM67 expression results in more than an 80% reduction in the activity of the CD11c promoter in hairy cells.

Modulation of CD11c promoter activity in hairy and nonhairy cells.

(A) Effect of the inhibition of AP-1 and Ras on CD11cpromoter activity in Mo hairy cells. The expression construct p11Wt containing nucleotides − 128 to + 36 of the CD11c gene promoter was transfected in parallel with the empty vector pATLuc into untreated Mo hairy cells mixed with pCMV, pTAM67, or pRasN17. The expression constructs pTAM67 and pRasN17 were generated by insertion into pCMV of, respectively, TAM67, encoding a dominant-negative mutant of c-Jun,34 orRasN17,36 encoding a dominant-negative mutant of Ras. After correction for transfection efficiency, the level ofluciferase reporter gene activity directed by p11Wt above that conferred by pATLuc in the presence of pCMV was assigned a value of 100% (UT). The level of activity directed by p11Wt in parallel transfections in the presence of pTAM67 (TAM67) or pRasN17 (RasN17) is expressed as a percentage of this value. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. Using the Student t test, the probability values for the reduction in CD11c promoter activity caused by pTAM67 and pRasN17 were calculated as P = .001 andP = .012, respectively. (B) Effect of exogenous expression of JunD and RasV12 on CD11c promoter activity in Jurkat nonhairy cells. The expression construct p11Wt was transfected into the cell line Jurkat in the presence of pRSV, RSV-hjD, pCMV, or pRasV12. The expression construct RSV-hjD contains the coding region of humanjunD inserted downstream of the Rous Sarcoma virus promoter.37 The plasmid pRSV was generated by removal of the junD coding region from RSV-hjD. The expression construct pRasV12 was generated by insertion ofRasV12,38 encoding a dominant-positive mutant of Ras, into pCMV. Transfected cells were left untreated for 16 hours prior to harvesting. The level of luciferase reporter gene activity directed by p11Wt above that conferred by pATLuc in the presence of pRSV and after correction for transfection efficiency is assigned a value of 100% (UT). The level of activity directed by p11Wt in parallel transfections in the presence of RSV-hjD is expressed as a percentage of this value (JunD). Similarly, the level ofluciferase reporter gene activity directed by p11Wt above that conferred by pATLuc in the presence of pCMV is assigned a value of 100% (UT) and the activity directed by p11Wt in parallel transfections in the presence of pRasV12 expressed relative to this value (RasV12). Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments.

Modulation of CD11c promoter activity in hairy and nonhairy cells.

(A) Effect of the inhibition of AP-1 and Ras on CD11cpromoter activity in Mo hairy cells. The expression construct p11Wt containing nucleotides − 128 to + 36 of the CD11c gene promoter was transfected in parallel with the empty vector pATLuc into untreated Mo hairy cells mixed with pCMV, pTAM67, or pRasN17. The expression constructs pTAM67 and pRasN17 were generated by insertion into pCMV of, respectively, TAM67, encoding a dominant-negative mutant of c-Jun,34 orRasN17,36 encoding a dominant-negative mutant of Ras. After correction for transfection efficiency, the level ofluciferase reporter gene activity directed by p11Wt above that conferred by pATLuc in the presence of pCMV was assigned a value of 100% (UT). The level of activity directed by p11Wt in parallel transfections in the presence of pTAM67 (TAM67) or pRasN17 (RasN17) is expressed as a percentage of this value. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. Using the Student t test, the probability values for the reduction in CD11c promoter activity caused by pTAM67 and pRasN17 were calculated as P = .001 andP = .012, respectively. (B) Effect of exogenous expression of JunD and RasV12 on CD11c promoter activity in Jurkat nonhairy cells. The expression construct p11Wt was transfected into the cell line Jurkat in the presence of pRSV, RSV-hjD, pCMV, or pRasV12. The expression construct RSV-hjD contains the coding region of humanjunD inserted downstream of the Rous Sarcoma virus promoter.37 The plasmid pRSV was generated by removal of the junD coding region from RSV-hjD. The expression construct pRasV12 was generated by insertion ofRasV12,38 encoding a dominant-positive mutant of Ras, into pCMV. Transfected cells were left untreated for 16 hours prior to harvesting. The level of luciferase reporter gene activity directed by p11Wt above that conferred by pATLuc in the presence of pRSV and after correction for transfection efficiency is assigned a value of 100% (UT). The level of activity directed by p11Wt in parallel transfections in the presence of RSV-hjD is expressed as a percentage of this value (JunD). Similarly, the level ofluciferase reporter gene activity directed by p11Wt above that conferred by pATLuc in the presence of pCMV is assigned a value of 100% (UT) and the activity directed by p11Wt in parallel transfections in the presence of pRasV12 expressed relative to this value (RasV12). Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments.

The use of the dominant-negative mutant TAM67 demonstrates that in hairy cells constitutive expression of AP-1 is necessary forCD11c promoter activity. Next, we wanted to determine if constitutive expression of JunD in nonhairy cells was sufficient to activate the CD11c promoter. In order to test this possibility we used the T-lymphocytic cell line Jurkat in which activation of the CD11c promoter has been demonstrated previously using phorbol esters (C.S.S., unpublished observation, October 1993). A construct constitutively expressing human JunD was transfected into Jurkat cells in combination with either pATLuc or p11Wt (Figure 6B). In the presence of exogenous JunD, the level of luciferase activity directed by p11Wt reached, on average, 154 times that conferred by pATLuc. In the presence of the plasmid vector empty of junD coding sequences, p11Wt produced levels of activity that were, on average, 158-fold above the level directed by pATLuc. Consequently, in isolation, constitutive JunD expression appears insufficient to activate the CD11c promoter in nonhairy cells.

Ras activation is necessary for CD11c promoter activity in hairy cells and sufficient to activate the CD11cpromoter in nonhairy cells

JunD is a member of the AP-1 family of transcription factors. The function of this family is subject to a host of control mechanisms.39 Because the simple overexpression of JunD fails to activate the CD11c promoter in nonhairy cells, abnormalities in these upstream control mechanisms may account for the activity of JunD in hairy cells. One of the principal means by which AP-1 function is controlled is by phosphorylation events mediated by cascades of c-Jun NH2-terminal/stress-activated protein kinases (JNK/SAPK).39 An early event in the activation of JNK/SAPK is activation of the products of the rasproto-oncogenes. Consequently, we sought to determine the role of Ras in CD11c expression. First, we used the rasdominant-negative mutant RasN1736 in transient transfection studies of hairy cells. In the hairy cell line Mo, expression of RasN17 caused a 36% reduction in the transcriptional activity of the CD11c promoter (Figure 6A). These results demonstrated that Ras activation, like AP-1 production, contributes to the expression of the CD11c promoter in hairy cells. Next, we used the ras dominant-positive mutantRasV1238 in transient transfection studies of the nonhairy cell line Jurkat. In contrast to constitutive JunD expression, constitutive Ras activation resulted in the induction of the CD11c promoter. (Figure 6B). Specifically,RasV12 induced 3.5-fold the transcriptional activity of theCD11c promoter present in p11Wt. This induced level of transcription averaged 131 times the level of transcription exhibited by the promoter-less construct pATLuc also treated withRasV12. Thus, in nonhairy cells constitutive Ras activation causes the activity of CD11c promoter to rise to levels equivalent to those seen in hairy cells.

An inhibitor of Ras signaling alters the activity of theCD11c promoter in hairy cells

Our experiments with dominant-positive and dominant-negative mutants indicate that Ras plays an important role in controlling the activity of the CD11c promoter. Ras influences gene expression through 4 main signaling pathways. The central components of these distinct but interrelated pathways are Raf/MEK/ERK, Rac/Rho, Ral guanine exchange factors, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt.40-46 The Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is inhibited by the drug U0126, which blocks the activity of MEK1/2.47 We treated the 3 hairy cell lines Mo, EH, and HK with U0126 to further verify the involvement of Ras in constitutive expression of the CD11c promoter. Following transfection with the construct p11Wt, cells were treated with 8 μM U0126 for 24 hours prior to harvesting and the measurement of luciferase and galactosidase activities (Figure 7). This series of transfections demonstrated that U0126 does indeed influence CD11c promoter activity in hairy cells. However, this influence is clearly cell-specific, with U0126 inhibiting by 54% promoter activity in EH cells but inducing activity by 54% and 57% in Mo and HK cells, respectively. These results indicate that in different hairy cells different Ras signaling pathways are involved in drivingCD11c expression. Thus, the pathways in EH cells are MEK1/2 dependent, whereas in Mo and HK cells they are MEK1/2 independent.

Effect of the Ras signaling inhibitor U0126 onCD11c promoter activity in hairy cells.

The expression construct p11Wt was transfected into the hairy cell lines Mo, EH, and HK in parallel with the empty vector pATLuc. Transfected cells were then either left untreated or treated for 24 hours with 8 μM U0126. The level of luciferase reporter gene activity directed by p11Wt above that conferred by pATLuc in the absence of treatment with U0126 and after correction for transfection efficiency is assigned a value of 100% (UT). The level of activity directed by p11Wt in parallel transfections in the presence of U0126 is expressed as a percentage of this value. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. The Student t test was used to determine the probability values for the changes in promoter activity caused by treatment with U0126. These values for Mo, HK, and EH cells wereP = .028, P = .105, andP = .001, respectively.

Effect of the Ras signaling inhibitor U0126 onCD11c promoter activity in hairy cells.

The expression construct p11Wt was transfected into the hairy cell lines Mo, EH, and HK in parallel with the empty vector pATLuc. Transfected cells were then either left untreated or treated for 24 hours with 8 μM U0126. The level of luciferase reporter gene activity directed by p11Wt above that conferred by pATLuc in the absence of treatment with U0126 and after correction for transfection efficiency is assigned a value of 100% (UT). The level of activity directed by p11Wt in parallel transfections in the presence of U0126 is expressed as a percentage of this value. Each bar represents the mean ± the standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. The Student t test was used to determine the probability values for the changes in promoter activity caused by treatment with U0126. These values for Mo, HK, and EH cells wereP = .028, P = .105, andP = .001, respectively.

U0126 reduces cell-surface expression of CD11c

In EH hairy cells the Ras signaling inhibitor U0126 represses theCD11c gene promoter when the promoter is present in an extrachromosomal plasmid (Figure 7). Therefore, next we investigated the possibility that U0126 also causes a reduction in surface expression of the CD11c protein, which would reflect repression of the endogenous CD11c gene. In 3 independent experiments, EH cells were either left untreated or treated in parallel for 48 hours with 8 μM U0126, and then surface expression of CD11c was assessed using flow cytometry (Table 1). This analysis established that treatment with U0126 causes, on average, a 44% decrease in CD11c expression. Consequently, in EH cells inhibition of Ras signaling through MEK1/2 inhibits endogenous as well as exogenous CD11c expression.

Effect of U0126 on the surface expression of CD11c

| Experiment no. . | Percentage of cells CD11c+ . | Percentage drop in cells CD11c+ . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated . | U0126 . | ||

| 1 | 17 | 2.5 | 85.3 |

| 2 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 34.8 |

| 3 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 23.2 |

| 4 | 8.5 | 1.3 | 84.7 |

| 5 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 33.3 |

| 6 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 44.4 |

| 7 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 24.4 |

| 8 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 23.8 |

| Experiment no. . | Percentage of cells CD11c+ . | Percentage drop in cells CD11c+ . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated . | U0126 . | ||

| 1 | 17 | 2.5 | 85.3 |

| 2 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 34.8 |

| 3 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 23.2 |

| 4 | 8.5 | 1.3 | 84.7 |

| 5 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 33.3 |

| 6 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 44.4 |

| 7 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 24.4 |

| 8 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 23.8 |

The hairy cell line EH was cultured for 48 hours in the absence of treatment or, in parallel, with 8 μM U0126. Flow cytometric analysis was then performed using a CD11c-specific antibody and an isotype-matched control. The number of cells bound by the control antibody was subtracted from the number bound by the CD11c antibody, such that the percentage of cells specifically bound by the CD11c antibody could be calculated. This percentage, derived from cells untreated or treated with U0126, is presented from a total of 8 independent experiments. Also presented is the percentage drop caused by U0126 in the number of cells expressing CD11c. The mean percentage drop in cells expressing CD11c was calculated as 44.2% with a standard deviation of ± 26.1%. The Student t test yielded a statistically significant probability value for the drop in CD11c expression of 0.03.

U0126 specifically reduces the proliferation of hairy cells

Abnormal expression of CD11c represents one of the molecular hallmarks of HCL. The finding that this expression is dependent upon Ras signaling through MEK1/2 suggests that inhibition of this pathway may represent a useful therapeutic strategy. Consequently, we assessed the ability of the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 to block HCL proliferation (Figure 8). After treatment with 8 μM U0126 for 24, 48, and 72 hours the number of EH hairy cells was reduced, on average, by 12%, 33%, and 39%, respectively, relative to untreated controls. In contrast, treatment of the promonocytic cell line U937, which was derived from a patient with diffuse histiocytic lymphoma,48 caused no significant change in proliferation. Therefore, inhibition of MEK1/2 appears to specifically inhibit the proliferation of hairy cells.

Effect of U0126 on cell proliferation.

The hairy cell line EH and the promonocytic cell line U937 were either left untreated or equal numbers were treated in parallel with 8 μM U0126. After 24, 48, and 72 hours cells were counted and the number of untreated cells assigned a value of 100%. The number of treated cells is expressed as a percentage of this value. The bars depicting analysis of EH proliferation represent the mean ± SD of 6 independent experiments. The bars depicting analysis of U937 proliferation represent the mean ± SD of 5 independent experiments. The Student t test was used to derive probabilities of statistical significance. The P values for the drop in EH cell number after 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment with U0126 were .015, .001, and .000, respectively. The P values for the change in U937 cell number after 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment were .241, .089, and .203, respectively.

Effect of U0126 on cell proliferation.

The hairy cell line EH and the promonocytic cell line U937 were either left untreated or equal numbers were treated in parallel with 8 μM U0126. After 24, 48, and 72 hours cells were counted and the number of untreated cells assigned a value of 100%. The number of treated cells is expressed as a percentage of this value. The bars depicting analysis of EH proliferation represent the mean ± SD of 6 independent experiments. The bars depicting analysis of U937 proliferation represent the mean ± SD of 5 independent experiments. The Student t test was used to derive probabilities of statistical significance. The P values for the drop in EH cell number after 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment with U0126 were .015, .001, and .000, respectively. The P values for the change in U937 cell number after 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment were .241, .089, and .203, respectively.

Discussion

Under normal circumstances CD11c gene expression is largely restricted to differentiating myeloid cells and a limited set of activated lymphocytes. However, in HCL, CD11c is constitutively expressed on the surface of the neoplastic lymphocytes and represents a diagnostic marker for the disease. Our transfection analysis established that constitutive expression of the CD11c gene in hairy cells is directed by the promoter region extending from 128 bp upstream to 36 bp downstream of the 5′ major transcription initiation site.

Within the CD11c promoter, 8 individualcis-acting control elements were identified and designated Boxes A to H. Mutation of these elements established that Box E is the most critical to the transcriptional activity of the CD11cpromoter in hairy cells, activated myeloid cells, and activated lymphocytic cells. Box E interacts with the AP-1 family of transcription factors. EMSA analysis demonstrated that AP-1 expression correlates with the activity of the CD11c promoter. Thus, AP-1 is constitutively expressed in hairy cells and is induced in nonhairy cells concomitant with induction of CD11c gene expression. Expression of the AP-1 family is normally transient and tightly controlled as these factors regulate the progression of the cell cycle during cellular proliferation and differentiation.49 Consequently, the chronic constitutive expression of AP-1 exhibited by hairy cells is abnormal. A breakdown in control mechanisms, resulting in persistent AP-1 expression and chronic cellular proliferation, has been implicated in the development of melanoma, brain tumors, ovarian cancer, and asbestos-induced cancer,50-53 and the induction of malignant cell transformation in vitro.54-58 Our work suggests that such chronic cell proliferation, induced by persistent AP-1 expression, may contribute to the pathogenesis of HCL.

The AP-1 complex induced in nonhairy cells upon phorbol ester treatment is composed of a mixture of JunD, c-Jun, JunB, and members of the Fos family. However, in the AP-1 complex constitutively expressed in hairy cells only JunD was detected. Although constitutive expression of JunD appears linked to HCL, our transfection studies indicate that chronic expression of JunD is not sufficient to induce CD11cpromoter activity in nonhairy cells. Several explanations of these observations are possible. The first is that our transfection analyses used an expression construct that produced wild-type JunD, and hairy cells may produce mutant JunD. In this regard it is worthy of note that several AP-1 gene mutations, including mutations of junD, have been implicated in oncogenesis.59-68 Whether such mutations contribute to the neoplastic transformation responsible for HCL remains to be established. Other explanations as to why chronic JunD expression fails to induce the CD11c promoter in nonhairy cells may lie in its activity being controlled by the formation of heterodimers and by upstream control mechanisms. These interacting partners and upstream mechanisms are probably intact in nonhairy cells but may be defective in hairy cells.

HCL is not the only hematopoietic malignancy in which constitutive expression of the proto-oncogene junD has been observed. Previous studies have shown that adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) are both associated with chronic expression of JunD.69,70 HCL, ATL, and CTCL are all tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase positive, are associated with infection with types of the human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV), are slow-developing diseases, and have neoplastic lymphocytes that move out of the circulation to infiltrate other areas of the body.71-76 In ATL and CTCL, infiltration occurs in the skin. In HCL, infiltration can also occur in the skin but is more common in the bone marrow, spleen, and liver. The related nature of HCL, ATL, and CTCL is further underscored by the finding that HCL and ATL as well as HCL and CTCL can coexist in the same patient.77-81 In addition, HCL, ATL, and CTCL share the characteristic of being amenable to treatment with pentostatin or chlorodeoxyadenosine.82-86 The molecular and pathogenic similarities of HCL, ATL, and CTCL tend to suggest these malignancies share common origins.

The mechanisms by which the expression of the AP-1 family is controlled act both at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level.59,60,87-100 The posttranscriptional mechanisms include regulation of mRNA stability and the redox modification, phosphorylation, and dimerization of the translated proteins. Phosphorylation is regulated by kinase cascades mediated by the Ras, Rac, and Cdc42 small guanosine triphosphate–binding proteins.101-103 In addition, the products of thedbl and ost proto-oncogenes, which act as exchange factors for Cdc42 and Rac, have also been shown to activate AP-1 kinase signaling.102-105 The activity of Rac and Cdc42 in HCL is particularly intriguing given that these proteins have been shown to regulate the formation of lamellipodia and microspikes/filopodia, respectively.106 107 It is particularly provocative that the formation of these distinct cytoskeletal structures is characteristic of HCL.

The products of the ras proto-oncogenes act upstream of both Rac and Cdc42. In addition, Ras can transform fibroblasts in cooperation with JunD,108 and H-Ras has been shown to be chronically expressed in the hairy cell line ESKOL.109Consequently, we envisioned that chronic Ras activation may play a role in the transformation process associated with HCL and may explain the characteristic appearance of the hairy cell membrane. We sought to determine the role of Ras in HCL and CD11c expression first by inhibiting its expression with the dominant-negative mutantRasN17. The use of this mutant in transient transfection assays inhibited CD11c promoter activity in Mo hairy cells. Consequently, Ras activation appears to contribute to CD11cexpression in hairy cells. Next, we expressed in nonhairy cells the dominant-positive ras mutant RasV12. In contrast to exogenous expression of JunD, exogenous expression of RasV12 induced the activity of the CD11c promoter in nonhairy cells. Consequently, Ras activation appears sufficient to induce theCD11c promoter.

Ras signals changes in gene expression through 4 main pathways.40-46 One of these pathways is mediated by the kinases MEK1 and MEK2, which are specifically inhibited with the drug U0126.47 Consequently, we used U0126 to further demonstrate the role of Ras in controlling hairy cell expression ofCD11c. In the hairy cell line EH, U0126 repressed both the activity of the CD11c promoter and the surface expression of the CD11c protein. However, in the hairy cell lines Mo and HK, U0126 activated the CD11c promoter. Consequently, in EH cells, Ras signals to the CD11c promoter in a manner dependent upon MEK1/2, whereas in Mo and HK cells it signals in a way that is MEK1/2 independent. These results suggest that in EH cells, activating mutations are present at or upstream of MEK1/2 in the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway of Ras signaling. U0126 then acts to block the downstream events resulting from these mutations including expression ofCD11c. In contrast, our data suggest that in Mo and HK cells, activating mutations are present either downstream of MEK1/2 and/or in Ras signaling pathways other than that composed of Raf/MEK and ERK. Under these circumstances, treatment with U0126 serves only to divert signaling to occur more vigorously down alternative Ras pathways, causing CD11c induction.

In conclusion, the data presented here establish a link between HCL and activation of the proto-oncogenes junD and ras. These findings thus provide a basis for the development of new therapeutic strategies. The potential for development of such novel approaches to the treatement of HCL is indicated by the observation that the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 specifically blocks the proliferation of the hairy cell line EH.

We would like to thank Stratford May, Ken Bridges, Tom Wileman, and Guy Faguet for providing, respectively, the cell lines MEG-01, K562, Jurkat, and EH and HK. James Brayer provided expert technical assistance and Gregory Tyler provided expert advice relating to the culture of the MEG-01 cell line. Russell L. McBride provided invaluable help in the culturing of the hairy cell line HK, and we are indebted to Michael Birrer for the use of his pCMV and pTAM67 constructs. We would like to thank John Kyriakis for kindly providing the expression constructs pRasN17 and pRasV12 and Yosef Shaul for providing the expression construct RSV-hjD. Finally, we would like to thank Alessandro Alessandrini for invaluable discussions during the preparation of the manuscript.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 6, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0324.

Supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique; the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale; National Institutes of Health grants DK50305, DK43351, and DK50779; grant DHP-116 from the American Cancer Society; a research grant from Ortho Biotech; a Cancer Research Institute Fellowship award (C.S.S.); and an American Cancer Society Fellowship award (O.C.F.). Additional support was provided by grant DAMD17-00-1-0255. In regard to this grant, the US Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity (Fort Detrick, MD) is the awarding and administering acquisition office.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Carl Simon Shelley, Renal Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, 149 13th St, Charlestown, MA 02129; e-mail: shelley@receptor.mgh.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal