Abstract

Two common features in human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and hematologic malignancies including multiple myeloma are elevated serum levels of β2-microglobulin (β2M) and activation or inhibition of the immune system. We hypothesized that β2M at high concentrations may have a negative impact on the immune system. In this study, we examined the effects of β2M on monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs). The addition of β2M (more than 10 μg/mL) to the cultures reduced cell yield, inhibited the up-regulation of surface expression of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)–ABC, CD1a, and CD80, diminished their ability to activate T cells, and compromised generation of the type-1 T-cell response induced in allogeneic mixed-lymphocyte reaction. Compared with control MoDCs, β2M-treated cells produced more interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and IL-10. β2M-treated cells expressed significantly fewer surface CD83, HLA-ABC, costimulatory molecules, and adhesion molecules and were less potent at stimulating allospecific T cells after an additional 48-hour culture in the presence of tumor necrosis factor-α and IL-1β. During cell culture, β2M down-regulated the expression of phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), and mitogen-induced extracellular kinase (MEK), inhibited nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and activated signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) in treated cells, all of which are involved in cell differentiation and proliferation. Thus, our study demonstrates that β2M at high concentrations retards the generation of MoDCs, which may involve down-regulation of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules, inactivation of Raf/MEK/ERK cascade and NF-κB, and activation of STAT3, and it merits further study to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Introduction

β2-Microglobulin (β2M) is an 11.6-kDa nonglycosylated polypeptide composed of 100 amino acids. It is the invariant chain of the major histocompatibility (MHC) class 1 molecules on the cell surface of all nucleated cells. Its best-characterized function is to interact with and stabilize the tertiary structure of the MHC class 1 α-chain.1 Because it is noncovalently associated with the α-chain and has no direct attachment to the cell membrane, β2M on the cell surface can exchange with free β2M present in serum-containing medium.2,3 Free β2M is found in body fluids under physiologic conditions as a result of shedding from cell surfaces or intracellular release. β2M is almost exclusively catabolized within the kidney; 95% to 100% of circulating β2M is eliminated through glomerular filtration.4 In healthy persons, the serum concentration of β2M is usually less than 2 mg/L, and the urinary excretion is less than 400 μg/24 hours.5 6

Two of the common features among diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS),7,8 autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis9,10 and Sjögren syndrome,11 and hematologic malignancies including multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia,12-15 are elevated serum levels of β2M and activation or inhibition of the immune system. In persons infected with HIV, high levels of serum β2M correlate with the progression to AIDS,7,8 whereas in the hematologic malignancies, the levels correlate with poor prognosis.13 14 Thus, based on the importance of β2M under physiologic and pathologic conditions, we hypothesized that β2M is not only a surrogate for viral or tumor burdens or a byproduct of immune activation but, at high concentrations, may have negative effects on the immune system.

Dendritic cells (DCs) serve as the sentinels of the immune system (for review, see Banchereau and Steinman16). In their immature state, DCs reside in peripheral tissues, where they survey for incoming pathogens. Encounter with pathogens leads to DC activation and migration to secondary lymphoid organs, where they trigger a specific T-cell response. DCs are also the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs); they are not only the cells that can stimulate quiescent, naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B cells and initiate primary immune responses, they can also induce a strong secondary immune response with relatively small numbers of DCs and low levels of antigen. Furthermore, DCs are involved in the polarization of T-cell responses through secreted cytokines and induction of tolerance through the deletion of self-reactive thymocytes and the anergy of mature T cells.16 Given their central role in controlling immunity, DCs are logical targets for many clinical situations that involve T cells, such as transplantation, allergy, autoimmune disease, resistance to infection and to tumors, immunodeficiency, and vaccination. Thus, we had chosen, in the present study, DCs as the target to test our hypothesis that β2M may have negative effects on the immune system. Because sufficient numbers of DCs for in vitro tests can readily be generated from peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes, we examined the effects of β2M on monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs).

Materials and methods

Reagents

Human β2M protein purified from urine was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO), and recombinant human β2M was from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (La Jolla, CA). According to the manufacturers, the purity of the proteins is greater than 98% by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). To ensure their purity, we also analyzed the proteins with SDS-PAGE, with 4.5% stacking and 15% resolving gel under denaturing conditions. Then 10 to 20 μg protein was loaded, and no contaminating proteins were detected (data not shown). Protease inhibitor cocktail, phycoerythrin (PE)– or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated monoclonal antibodies against human histocompatibility leukocyte antigens (HLA)–ABC, HLA-DR, CD1a, CD83, CD80, CD86, CD54, CD40, and mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) isotype control were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Anti-CD14 antibody-conjugated microbeads were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Polyclonal antibodies against IκB-α and IκB-β were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and antibodies against mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (MAPKs), phosphorylated inhibition of nuclear factor-κB (IκB)–α, and signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) at Tyr705 were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Recombinant interleukin (IL)–4, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α, and IL-1β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) was purchased from Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark). 3[H]-Thymidine and Ficoll-Hypaque were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ).

Generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells

MoDCs were generated from peripheral blood monocytes using the standard protocols.17 18 Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the blood of healthy donors using Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation. In most of the studies, MoDCs were obtained by incubating PBMCs on a plastic surface at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 hours to allow monocyte adhesion. After incubation, nonadherent cells were removed, and plates were vigorously (at least 3 times) washed to eliminate contaminating cells. In some experiments, monocytes were purified from PBMCs by positive selection using a MACS column with anti-CD14 antibody-conjugated microbeads. The positively selected fraction contained more than 95% of CD14+ monocytes. Adherent cells or purified CD14+ cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 supplement with 10% fetal calf serum, 1 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, GM-CSF (100 ng/mL) and IL-4 (100 ng/mL) for 7 days in a humidified incubator at 37°C in 5% CO2, with the further addition of cytokines on day 3 by replacing 50% of the medium containing the cytokines. After 7 days of culture, immature MoDCs were harvested for testing. To induce maturation, TNF-α (10 ng/mL) and IL-1β (10 ng/mL) were added to the 7-day culture, and cells were incubated for another 48 hours. On day 9, mature MoDCs were harvested for testing.

β2M treatment of cells

To examine its effects on MoDCs, β2M was added to the cells at the beginning of culture (day 0). No additional β2M was added on day 3 when 50% of the medium was replaced or on day 7 when cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β were added to mature MoDCs. In some experiments, β2M was added to cultures on day 3 to examine whether delayed addition of the protein could affect the generation of MoDCs.

Flow cytometry analysis

MoDCs harvested on days 7 and 9 were analyzed for their surface expression of relevant molecules. This was carried out using a fluorescence-activated cell scan (FACScan) (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and was analyzed using the Lysis II program. Briefly, cells were first washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by the addition of PE- and FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. After incubation on ice for 30 minutes, the cells were washed twice, resuspended in PBS, and made ready for analysis. Controls consisted of cells stained with irrelevant mouse IgG antibodies.

Measurement of cytokines by cytometric bead array analysis

Kits of cytometric bead array analysis for the detection of cytokines19—including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, TNF-α (inflammatory cytokine kit), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, interferon (IFN)–γ, and TNF-α (T-cell subset cytokine kit)—were purchased from PharMingen, and assay was performed by the Core Facility at the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Briefly, supernatants of MoDC or T-cell culture were collected and kept frozen at −80°C until analysis. When assayed, the supernatants were mixed with human cytokine-captured beads, and PE-conjugated detection reagent was added and incubated for 3 hours at room temperature. After incubation, the beads were washed 3 times, resuspended in PBS, and ready for flow cytometer analysis.

Mixed-lymphocyte reaction

To examine the capacity of MoDCs to activate allogeneic T cells, mixed-lymphocyte reaction (MLR) was used. Briefly, purified allogeneic T cells (5 × 104 cells/100μL/well) were seeded in 96-well U-bottom tissue- culture plates. MoDCs at various numbers were added and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 6 days. Sixteen hours before harvest, 1 μCi (0.037 MBq)3[H]-thymidine was added to each well. Cells were harvested, and radioactivity was measured in a β-liquid scintillation analyzer (Packard, Meriden, CT). Results are expressed as the mean of triplicate cultures.

Presentation of soluble antigen by dendritic cells

To examine the capacity of MoDCs to capture and present soluble antigen and to activate autologous antigen-specific T cells, assay for T-cell response to recall antigen PPD was performed using the cells of healthy blood donors who had been immunized with bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccines. Results showed a positive T-cell proliferative response against PPD in vitro. MoDCs were pulsed with 2.5 μg/mL PPD for 2 hours, washed 3 times with PBS, and cultured with purified autologous T cells for 6 days. T-cell proliferative response was measured by using overnight incubation with3[H]-thymidine (1.0 μCi [0.037 MBq]/well), as described in MLR assay.

Western blot analysis

To detect intracellular signaling associated with β2M treatment, Western blot was used to analyze MAPKs and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and STAT3 expression by cultured cells. To detect MAPKs and IκB-α and IκB-β, cells were cultured with or without β2M, harvested, washed, and lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM Na3N3, 1% Triton X-100, 1% NP-40, 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail). For the determination of phosphorylated MAPKs, IκB-α and STAT3 (Tyr705), cells were lysed directly in Laemmli buffer (Sigma). Samples were centrifuged at 12 000g, and the supernatants were collected, boiled, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose membranes and subsequent blocking, membranes were immunoblotted with the respective antibodies against phosphorylated MAPKs, IκB, or STAT3 and were visualized with alkaline phosphatase–conjugated secondary antibodies; this was followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and autoradiography. For protein quantification, blots were scanned and analyzed by spot densitometry using the AlphaImager 2200 Documentation and Analysis System (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Results are expressed as the average value of pixels enclosed (AVG). AVG is calculated as the sum of all the pixel values after background correction divided by area.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared from cultured cells using the Nu-CLEAR extraction kit (N-XTRACT; Sigma). NF-κB binding reactions were carried out with 5 μg nuclear proteins and 1 μg NF-κB probe according to manual protocol (electrophoretic mobility shift assay [EMSA] gel-shift kits; Panomics, Redwood City, CA). The whole sample was then loaded on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate-EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) buffer. After transfer to nylon Biodye-B membrane (Pall, East Hills, NY) and subsequent blocking and washing, the membranes were visualized using chemiluminescence imaging.

Statistical analysis

Student t test was used to compare various experimental groups; significance was set at P < .05.

Results

β2M impaired cell yield and morphology

To examine the effects of β2M on MoDCs, various concentrations of the protein were added to the cells at the beginning of the culture. In these experiments, urine-derived β2M and recombinant β2M were used. During culture, the differences in cell morphology could be observed as early as day 3; cells cultured in medium without β2M appeared as mostly floating, single cells with enlarged, DC-like morphology, whereas cells cultured with the addition of β2M, especially at more than 10 μg/mL, remained mostly adherent and smaller and had monocyte-like shapes. Figure 1A depicts the morphology of DCs cultured for 7 days in medium only or in medium with the addition of β2M (20 μg/mL). It is obvious that cells in medium only appeared as large, floating cells with a typical DC-like morphology, whereas cells cultured with β2M, either urine-derived or recombinant, were smaller and had poorly differentiated morphology.

Morphologic features and yields of immature MoDCs.

(A) Morphologic features of immature MoDCs harvested on day 7 of culture with or without the addition of 20 μg/mL urine-derived or recombinant β2M. Representative fields of differential interference contrast microscopy (original magnification × 300) of more than 5 separate experiments are shown. (B) Yields of immature MoDCs (viable cell counts of big cells only) from day 7 culture with or without the addition of varying concentrations (2.5-40 μg/mL) of urine-derived (U-β2M) or recombinant (R-β2M) β2M. Data are expressed as a percentage of the control. Mean ± SEM from 3 experiments are shown. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Morphologic features and yields of immature MoDCs.

(A) Morphologic features of immature MoDCs harvested on day 7 of culture with or without the addition of 20 μg/mL urine-derived or recombinant β2M. Representative fields of differential interference contrast microscopy (original magnification × 300) of more than 5 separate experiments are shown. (B) Yields of immature MoDCs (viable cell counts of big cells only) from day 7 culture with or without the addition of varying concentrations (2.5-40 μg/mL) of urine-derived (U-β2M) or recombinant (R-β2M) β2M. Data are expressed as a percentage of the control. Mean ± SEM from 3 experiments are shown. *P < .05; **P < .01.

In addition to the morphologic changes, lower cell yield was also observed in cultures with β2M, which was determined by viable cell counts. Figure 1B shows the results of cell recovery from cultures with or without the addition of different concentrations of β2M. It is evident that β2M reduced the yields of MoDCs, and a significantly lower cell recovery was observed in cultures with the addition of 10 μg/mL or more β2M (P < .05 and P < .01). We examined whether the induction of apoptosis by β2M was responsible for the low cell yield, using flow cytometry analysis with FITC-conjugated Annexin-V and propidium iodide. No differences were observed between the cultures with or without β2M. In these and the following studies, PBMCs from 5 healthy blood donors were used to generate MoDCs.

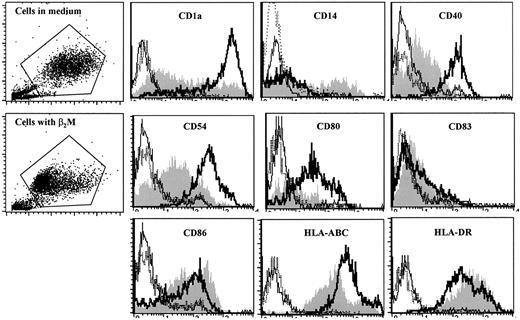

β2M inhibited the up-regulation of surface MHC class 1 and costimulatory molecules

We next examined the surface expression of DC-related molecules by cultured cells. In these experiments, cells were cultured with or without the addition of 20 μg/mL β2M for 7 days. Selection of the concentration of 20 μg/mL β2M for these and other experiments in this study was based on our preliminary tests (data not shown), the results depicted in Figure 1B, and the commonly found serum levels of β2M under pathologic conditions.7-15 After culture, cells were washed 3 times and stained with the antibodies. As shown by the representative histograms of flow cytometry analysis of MoDCs with recombinant β2M on day 7 (Figure 2), surface expression of CD1a, CD40, CD54, CD80, and HLA-ABC molecules was significantly (1.5- to 10-fold; P < .05 andP < 0.01) lower on β2M-treated cells. Interestingly, the expression of CD86 and HLA-DR was increased on β2M-treated cells (1.6- to 2.5-fold;P < .05). CD14 expression was detected in a small portion of the cells in culture with β2M but was absent in control MoDCs, and CD83 levels were low in all the cells (Figure 2). Prolonged culture of the cells in medium supplemented with GM-CSF and IL-4 did not restore surface expression of these molecules, because cells analyzed on days 8 to 10 had similar defects (data not shown). These results were obtained with urine-derived β2M (data not shown) and were also reproduced in at least 5 independent experiments.

Phenotypic features of immature MoDCs.

MoDCs were harvested on day 7 of culture with (shaded histograms) or without (open histograms, thick lines) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. Open histograms with thin or broken lines represent control antibody staining of the cells. Representative histograms of 5 independent experiments are shown. Gates were set on the large-size cell populations.

Phenotypic features of immature MoDCs.

MoDCs were harvested on day 7 of culture with (shaded histograms) or without (open histograms, thick lines) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. Open histograms with thin or broken lines represent control antibody staining of the cells. Representative histograms of 5 independent experiments are shown. Gates were set on the large-size cell populations.

We also examined whether the delayed addition of β2M could affect the generation of MoDCs. We added the same concentrations of β2M to the cultures on day 3 and compared cells recovered from different cultures. No significant difference was observed in cell yield or morphology between cultures without the addition of β2M and those with β2M added on day 3 (data not shown). Flow cytometry analysis revealed no major changes in cell surface expression of the relevant molecules between the 2 cultures (data not shown). These results indicate that the presence of β2M in the first 3 days of culture played an important role in affecting the generation of MoDCs.

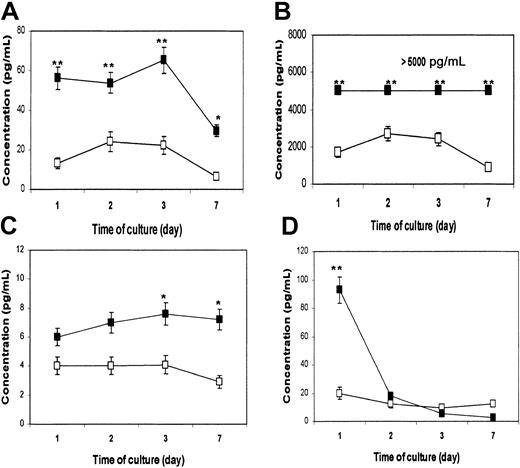

β2M altered cytokine secretion profiles of DCs

DCs are the most potent APCs. Not only are they required for the priming of native CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to initiate an immune response, they also play an active role in polarizing the immune response toward type-1 or type-2 T-cell responses.16 Cytokines secreted by DCs are instrumental to the process. Therefore, we wanted to examine whether β2M could also influence the cytokine secretion profile of treated cells. In these experiments, highly purified monocytes were used to generate MoDCs. Supernatants were collected from cultured cells on days 1, 2, 3, and 7, and a flow cytometry–based bead-array analysis was used to measure the relevant (inflammatory) cytokines. As evident by the results depicted in Figure 3, β2M treatment (20 μg/mL) significantly up-regulated the secretion of IL-6 (P < .01; Figure 3A), IL-8 (P < .01; Figure 3B), and IL-10 (P < .05; Figure 3C), though the concentrations of IL-10 secreted to the culture were lower than those of IL-6 and IL-8. Because of the limitation of the method, cytokine concentrations higher than 5000 pg/mL cannot be accurately measured and thus are expressed as more than 5000 pg/mL (Figure 3B). The concentration of TNF-α in culture with the addition of β2M was dramatically increased on day 1 (P < .01), but it declined to the same low levels found in control cell cultures from day 2 (Figure 3D). IL-12 was not detected in the supernatants of the cell cultures. No difference was found in other cytokines (data not shown). These results were reproduced by repeated experiments (n = 4) with urine-derived and recombinant β2M.

Cytokine secretion profile of immature MoDCs.

Cultures with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. Cytometric bead array analysis was used to measure the concentrations (pg/mL) of various cytokines in cell culture medium collected on days 1, 2, 3, and 7. Shown are the results (mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments) of cytokines IL-6 (A), IL-8 (B), IL-10 (C), and TNF-α (D). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Cytokine secretion profile of immature MoDCs.

Cultures with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. Cytometric bead array analysis was used to measure the concentrations (pg/mL) of various cytokines in cell culture medium collected on days 1, 2, 3, and 7. Shown are the results (mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments) of cytokines IL-6 (A), IL-8 (B), IL-10 (C), and TNF-α (D). *P < .05; **P < .01.

β2M treatment compromised MoDC capacity to present antigens and reduced IL-2 and IFN-γ production by activated T cells

Thus far, our results demonstrate that β2M treatment induced morphologic and phenotypic abnormalities and altered the cytokine-secretion profile in treated cells. It was likely that the function of the cells—that is, antigen presentation and induction of T-cell activation, which can be assessed by the capacity to activate allospecific T cells and to present recall antigens to autologous, antigen-specific T cells—was also compromised. Thus, experiments were performed to evaluate the function of cultured cells. First, we used allogeneic MLR to compare MoDCs with or without β2M treatment in their ability to activate allospecific T cells. Figure4A shows that cells treated with β2M induced a significantly weaker T-cell response than those induced by control MoDCs (P < .05). Moreover, analysis of cytokine secretion by the activated T cells, using the flow cytometry–based bead-array analysis, revealed that significantly lower amounts of IL-2 (P < .05) and IFN-γ (P < .01) were detected in the supernatants of T cells stimulated by β2M-treated cells (Figure 4B-C). The amount of TNF-α was also lower, but the difference was not statistically significant. IL-4 and IL-10 levels in the supernatants were low (less than 10 pg/mL), and no significant difference was noted (data not shown). No difference was observed in other cytokines (data not shown). These results indicate that the development of a polarized type 1 T-cell response in the allogeneic MLR culture20 21 was compromised when β2M-treated cells were used as the APCs.

Antigen-presentation capacity of cultured immature MoDCs.

(A) 3H-Thymidine incorporation (cpm × 103) in allogeneic MLR induced by MoDCs cultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. (B-C) Cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α (B), and IL-2 (C) secreted by allospecific T cells activated by MoDCs cultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL of recombinant β2M. Values above the bars represent the concentration of the indicated cytokines. Cytometric bead array analysis was used to measure cytokine concentrations in the medium of T-cell cultures (containing T cells [Tc] and DCs at a ratio of 100:1) on day 6. (D)3H-Thymidine incorporation (cpm × 103) in autologous T-cell response induced by PPD-pulsed (squares) or unpulsed (triangles) immature MoDCs cultured with (▪,▴) or without (■,▵) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. Mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments are shown. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Antigen-presentation capacity of cultured immature MoDCs.

(A) 3H-Thymidine incorporation (cpm × 103) in allogeneic MLR induced by MoDCs cultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. (B-C) Cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α (B), and IL-2 (C) secreted by allospecific T cells activated by MoDCs cultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL of recombinant β2M. Values above the bars represent the concentration of the indicated cytokines. Cytometric bead array analysis was used to measure cytokine concentrations in the medium of T-cell cultures (containing T cells [Tc] and DCs at a ratio of 100:1) on day 6. (D)3H-Thymidine incorporation (cpm × 103) in autologous T-cell response induced by PPD-pulsed (squares) or unpulsed (triangles) immature MoDCs cultured with (▪,▴) or without (■,▵) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. Mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments are shown. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Second, we compared the capacity of MoDCs to present PPD and to activate autologous specific T cells by using PBMCs from donors who responded positively to PPD stimulation in vitro. In these experiments, MoDCs were first pulsed with PPD for 2 hours, washed, and cocultured with autologous purified CD3+ T cells. As shown in Figure4D, the specific T-cell response was reduced when β2M-treated cells were used as the APCs (P < .05). T-cell responses induced by unpulsed MoDCs were low and no significant difference was found between unpulsed, β2M-treated and control MoDCs. Thus, our results provide direct evidence that β2M-treated cells have an impaired antigen-presentation capacity.

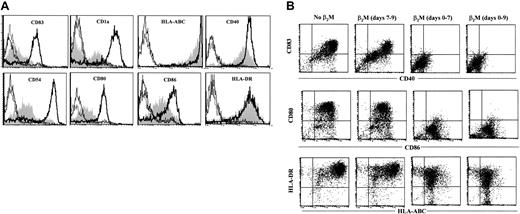

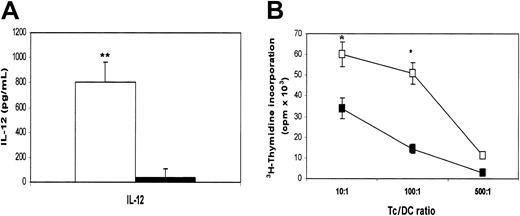

β2M-induced defects sustained after DC maturation

MoDCs were generated in medium in the presence or absence of β2M at 20 μg/mL. On day 7, cells were washed free of β2M, and recombinant TNF-α and IL-1β were added to the culture to induce DC maturation.17 18 After 48 hours, cells were harvested and analyzed for their phenotype and function. As shown in Figure 5A, β2M-treated (in the first 7 days) cells expressed significantly (1.5- to 10-fold) lower levels of CD83, CD1a, CD40, CD54, CD80, CD86, and HLA-ABC (P < .05 andP < .01), even though the expression of these molecules, except CD54 and CD86, had been up-regulated on β2M-pretreated cells following TNF-α and IL-1β treatment. CD1a expression was down-regulated, and that of HLA-DR was not different. As mentioned previously, most of the abnormalities were already present in immature β2M-treated cells. We have also examined the effects of β2M on the maturation of previously β2M-treated or untreated cells. As depicted in the representative experiments in Figure 5B, the addition of β2M on day 7 had few, if any, effects on the maturation of DCs. On the contrary, the presence of this protein from the beginning of the culture (days 0-7) inhibited the up-regulation of these molecules, and the further addition of β2M to the cultures during maturation (days 7-9) had no synergistic effects. As expected, the secretion of IL-12 was up-regulated in mature MoDCs (600-1000 pg/mL) but less so in β2M-pretreated cells (10-50 pg/mL; P < .01; Figure6A).

Phenotypic features of mature MoDCs harvested on day 9.

(A) Cells were cultured for the first 7 days in medium with (shaded) or without (open histograms, thick lines) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M, followed by an additional 48-hour culture in the presence of IL-1β and TNF-α. Open histograms with thin or broken lines represent control antibody staining of the cells. (B) Dot plots of flow cytometry analysis showing the effects of β2M during maturation (days 7-9) of previously (days 0-7) β2M-treated or untreated DCs. Representative histograms or dot plots of 5 independent experiments are shown. Gates were set on the large-size cell populations.

Phenotypic features of mature MoDCs harvested on day 9.

(A) Cells were cultured for the first 7 days in medium with (shaded) or without (open histograms, thick lines) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M, followed by an additional 48-hour culture in the presence of IL-1β and TNF-α. Open histograms with thin or broken lines represent control antibody staining of the cells. (B) Dot plots of flow cytometry analysis showing the effects of β2M during maturation (days 7-9) of previously (days 0-7) β2M-treated or untreated DCs. Representative histograms or dot plots of 5 independent experiments are shown. Gates were set on the large-size cell populations.

Cytokine secretion and function of mature MoDCs harvested on day 9.

(A) Secretion of IL-12 by mature MoDCs precultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M in the first 7 days. (B) 3H-Thymidine incorporation (cpm × 103) in allogeneic MLR induced by mature MoDCs precultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M in the first 7 days. Mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Cytokine secretion and function of mature MoDCs harvested on day 9.

(A) Secretion of IL-12 by mature MoDCs precultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M in the first 7 days. (B) 3H-Thymidine incorporation (cpm × 103) in allogeneic MLR induced by mature MoDCs precultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M in the first 7 days. Mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Furthermore, β2M-treated cells were also less potent than control MoDCs at stimulating allospecific T cells (P < .05) (Figure 6B). These defects remained even after prolonged maturation (up to 72 hours) with these cytokines or in cells cultured with CD40 ligand (data not shown). Thus, these results demonstrate that β2M-induced defects in these cells sustained even after the maturation of the cells.

β2M inhibited MAPK and NF-κB activity but activated STAT3 in treated cells

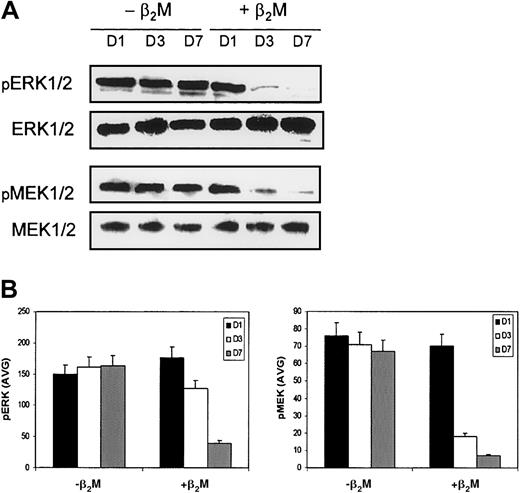

Our results demonstrate clearly that β2M retarded the differentiation of monocytes and altered their cytokine expression profiles. Because MAPKs play a critical role in the regulation of cell growth and differentiation and NF-κB and STAT3 are involved in the regulation of the expression of or in response to these cytokines, we examined the levels and activity of these molecules by Western blot analysis and EMSA. Cell lysates collected on days 1, 3, and 7 of the cultures were prepared for the analyses. Highly purified monocytes were used in these experiments to generate MoDCs. In this study, the expression of MAPK family members—phosphorylated extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), p38 MAPK, and SAPK/JNK—and of nonphosphorylated MAPKs, which could serve as controls for protein loading, was examined. As shown in Figure7, β2M treatment reduced the expression of phosphorylated ERK1 or ERK2 (pERK1/2) in the treated cells. Moreover, the expression of phosphorylated mitogen-induced extracellular kinase 1 (MEK1) and MEK2 (pMEK1/2), which are the upstream activators of ERK, was also down-regulated. Levels of nonphosphorylated ERK and MEK remained stable. No changes were observed in the expression of other MAPKs, including p38 MAPK or SAPK/JNK (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that the Raf/MEK/ERK MAP kinase cascade may be involved in β2M-mediated signaling.

Expression of MAPKs by MoDCs.

Culture in medium with (+β2M) or without (−β2M) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. (A) Western blots were made with cell lysates collected on day 1 (D1), day 3 (D3), and day 7 (D7) of the culture. MAPKs ERK1/2 and MEK1/2 were immunoblotted with specific antibodies. Phosphorylated (pERK1/2 and pMEK1/2) and nonphosphorylated (ERK1/2 and MEK1/2) MAPKs were detected. The latter could also serve as control for protein loading. Representative blots are shown. (B) Densitometric data (AVG) of pERK1/2 and pMEK1/2 represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Expression of MAPKs by MoDCs.

Culture in medium with (+β2M) or without (−β2M) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. (A) Western blots were made with cell lysates collected on day 1 (D1), day 3 (D3), and day 7 (D7) of the culture. MAPKs ERK1/2 and MEK1/2 were immunoblotted with specific antibodies. Phosphorylated (pERK1/2 and pMEK1/2) and nonphosphorylated (ERK1/2 and MEK1/2) MAPKs were detected. The latter could also serve as control for protein loading. Representative blots are shown. (B) Densitometric data (AVG) of pERK1/2 and pMEK1/2 represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

To detect NF-κB activity, we first examined the expression or activity of its inhibitors, IκB-α and IκB-β and phosphorylated IκB-α (pIκB-α), because the phosphorylation of serine residues on the IκB-α proteins (appeared as elevated levels of pIκB) by kinases marks them for destruction through the ubiquitination pathway, thereby allowing activation of the NF-κB complex (for review, see Baldwin22). As shown in Figure8, compared with those in medium only, cells cultured in the presence of β2M had higher levels of pIκB-α but lower levels of IκB-α on day 1; this gradually decreased (pIκB-α) or increased (IκB-α), respectively, during the culture. This suggests that NF-κB activity was high in β2M-treated cells on day 1 but declined thereafter. In contrast, the levels of pIκB-α were lower and those of IκB-α were higher in control cells on day 1. During culture, the levels of pIκB-α gradually increased, and those of IκB-α decreased, in control cells, suggesting increased activity of NF-κB during cell differentiation induced by IL-4 and GM-CSF. The level of IκB-β remained stable. These results correlated very well with NF-κB activity analyzed by EMSA (Figure 8). Collectively, these findings indicate that, though NF-κB activity was low in starting monocytes and was up-regulated during cell differentiation to MoDCs, its activity in β2M-treated cells was high initially but decreased thereafter.

Expression of IκB and NF-κB and STAT3 by MoDCs cultured in medium with (+β2M) or without (−β2M) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M.

(A) Western blots were made with cell lysates collected on day 1 (D1), day 3 (D3), and day 7 (D7) of culture. IκB-α and IκB-β, phosphorylated IκB-α (pIκB-α), STAT3, and phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) were immunoblotted with specific antibodies. NF-κB activity was analyzed by EMSA. Representative blots are shown. (B) Densitometric data (AVG) of pIκB-α and IκB-α represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Expression of IκB and NF-κB and STAT3 by MoDCs cultured in medium with (+β2M) or without (−β2M) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M.

(A) Western blots were made with cell lysates collected on day 1 (D1), day 3 (D3), and day 7 (D7) of culture. IκB-α and IκB-β, phosphorylated IκB-α (pIκB-α), STAT3, and phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) were immunoblotted with specific antibodies. NF-κB activity was analyzed by EMSA. Representative blots are shown. (B) Densitometric data (AVG) of pIκB-α and IκB-α represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments.

For the detection of STAT3 activity, we used an antibody to detect phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) at Tyr705, which is an activated form of the molecule. As shown by Figure 8, β2M treatment up-regulated the expression of pSTAT3 in treated cells and, thus, enhanced its activity. Little or no STAT3 activity was detected in cells cultured without the addition of β2M. No significant difference was observed in the expression of nonphosphorylated STAT3 protein between cells or in the same cells during culture.

Discussion

The present study was designed to investigate whether β2M at high concentrations has a negative impact on the immune system. As the first step, we examined the effects of β2M on the generation and function of MoDCs because DCs are the key player in the immune system, and it is now feasible to obtain substantial numbers of such cells from peripheral blood monocytes for in vitro experiments. Furthermore, it has been shown that a proportion of lymph node DCs is derived from monocytes in vivo.23 PBMCs from healthy blood donors were isolated, and adherent or purified monocytes were cultured in the presence or absence of purified human β2M at concentrations ranging from 2.5 μg/mL to 40 μg/mL. These represent the normal levels of β2M in healthy persons5,6 and elevated levels under pathologic conditions.7-15 According to the data collected in our Institute from more than 1000 myeloma patients, serum β2M can be as high as 80 mg/L (80 μg/mL). One might expect much higher concentrations of β2M in tumor sites. Our results demonstrated that, in the presence of high concentrations (more than 10 μg/mL) of β2M, the in vitro generation of MoDCs was retarded. This is evident by the low cell yield, poor morphology, and low expression of surface MHC class 1, CD1a, and costimulatory molecules CD40 and CD80 in treated cells. Furthermore, these cells had an impaired antigen-presentation capacity. Compared with control MoDCs, β2M-treated cells secreted high amounts of IL-6 and IL-8 and the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10. They induced significantly weaker allogeneic T-cell activation and PPD-specific T-cell responses and compromised DC capacity to mount a type 1 T-cell response (weaker IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion). These defects were sustained even after the maturation of MoDCs induced by culture with TNF-α and IL-1β for 48 hours. These results were seen and reproduced with highly purified human urine-derived β2M and recombinant β2M, indicating that the effects are indeed mediated by human β2M protein. Hence, our study provides direct evidence to support our hypothesis that β2M has negative effects on the immune system.

High levels of serum β2M are associated with the progression to AIDS in HIV-infected persons7,8 and with a poor prognosis in patients with hematologic malignancies.12-15 Based on the results that DCs differentiated from monocytes in the presence of high concentrations of β2M had an impaired antigen-presenting capacity and induced a compromised type 1 T-cell response, our findings may be compatible with the clinical arena seen in these conditions. The abnormalities may be attributed to the failure in the up-regulation of surface expression of MHC class 1 antigen, costimulatory molecule CD80 and adhesion molecule CD54 on the cells, and high amounts of IL-6 and IL-10 and low amounts of IL-12 secreted by the cells. These cytokines are known for their role as the negative or positive regulators of type 1 (CD4+ helper T cells [TH1] and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells) T-cell differentiation.24,25 In addition, these cytokines, especially IL-6, are growth and survival factors for tumor cells such as myeloma cells.26,27 Interestingly, high levels of IL-6 are found in the serum of HIV and multiple myeloma patients.26-28 Hence, it is conceivable that high levels of β2M might have contributed to disease progression through its negative effects on the immune system (eg, inhibition of the generation of virus- or tumor-specific CD4+TH1 and CD8+ CTL responses) and through directly promoting tumor cell growth and survival by secreted cytokines.

Although the mechanisms by which β2M-induced functional retardation in MoDCs are unknown, it is possible that the effect is mediated through the MHC class 1 molecules. Studies have shown that MHC class 1 molecules may serve as important signal-transducing molecules involved in the regulation or fine-tuning of immune responses (for review, see Skov29). Ligation of MHC class 1 molecules on T and B cells by mobilized antibodies triggered signal transduction, which is involved in responses ranging from anergy and apoptosis to cell proliferation and IL-2 production.29-32 Given that β2M is the invariant chain of the MHC class 1 molecules, the presence of high levels of β2M in the culture medium could have affected the balance and, thus, synthesis of the cellular β2M and the α-chain, as well as the expression and stability of surface MHC class 1 molecules. Indeed, it is evident that the treatment of cells with β2M down-regulated surface MHC class 1 expression. We speculate that high concentrations of exogenous β2M sent a negative feedback signal to the cells to synthesize less cellular β2M, which resulted in a reduced number of assembled MHC class 1 molecules in endoplasmic reticulum and fewer surface MHC class 1 molecules and triggered signal transduction in affected cells.

Our results also suggest that the MAPKs, NF-κB, and STAT3 are involved in signaling transduction in response to β2M treatment. During culture, we observed reduced expression of phosphorylated MAPK/ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) and their upstream activator, phosphorylated MEK1/2 (pMEK1/2), suggesting that β2M treatment suppressed the activation of the Raf/MEK/ERK signal transduction cascade, which is a vital mediator of a number of cellular fates, including cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, and survival (for review, see Lee and McCubrey33). Concomitantly, NF-κB activity, which was higher than control cell activity on day 1 of culture, was gradually reduced in β2M-treated cells. The transiently high level of TNF-α secreted by the cells (Figure 3D), which could be induced by the interaction of β2M with the cells and down-regulated by the inactivation of MAPKs and subsequently NF-κB, could have been responsible for the high NF-κB activity observed in β2M-treated cells on day 1 of culture. Because NF-κB is a common transcription factor of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway,33 it is possible that the reduced NF-κB activity in β2M-treated cells was the result of a suppressed Raf/MEK/ERK cascade. Alternatively or concomitantly, the increased secretion of IL-10 by the treated cells could also be responsible for the decreased NF-κB activity.34 In addition, we have observed an activation of STAT3 in β2M-treated cells, which may be induced by IL-6 secreted by the cells in an autocrine fashion. Binding of IL-6 with IL-6 receptor gp130 activates STAT3, which plays a central role in transmitting the signals from the membrane to the nucleus. These signals are also related to cell growth, differentiation, and survival.35 Thus, the inactivation of NF-κB and the activation of STAT3 may be responsible for β2M-induced differentiation retardation in treated cells. In line with this observation, it has been shown that IL-6 inhibited DC differentiation from its CD34+ progenitor cells,36 and the ligation of MHC class 1 molecules could also lead to the phosphorylation of STAT3.29 In addition, ample evidence indicates that NF-κB plays an important role in DC differentiation and function.37-39 Hence, further study is needed to explore the possible interactions among MHC class 1 molecules, MAPKs, NF-κB, and gp130/STAT3 pathways for the elucidation of the underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, our study suggests that elevated levels of β2M may be detrimental to the immune system. β2M-treated cells had reduced antigen-presentation capacity and induced compromised type 1 T-cell responses. High levels of β2M may also promote tumor growth and survival through cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-10 produced by the cells. β2M may mediate its effects through the stability and surface expression of MHC class 1 molecules, which in turn or together with cytokines IL-6 and IL-10, inhibited the MAP kinase Raf/MEK/ERK pathway and NF-κB activity and activated STAT3, leading to retardation in the differentiation of monocytes to MoDCs. Indeed, our preliminary study demonstrated that neutralizing antibodies against IL-10 and IL-6 could partially abrogate the effects of β2M on the cells (data not shown). Thus, these novel findings may shed light on the mechanisms of immune suppression in hematologic malignancies and in HIV infection and AIDS, and they are important for the development of effective immunotherapies for these diseases.

We thank Dr Joshua Epstein for his help with differential interference contrast microscopy.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, January 16, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002- 11-3368.

Supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (PO1-CA55819 and RO1-CA96569) and by Translational Research Grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (6548-00 and 6041-03).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Qing Yi, Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham St, Slot 776, Little Rock, AR; e-mail:yiqing@uams.edu.

![Fig. 4. Antigen-presentation capacity of cultured immature MoDCs. / (A) 3H-Thymidine incorporation (cpm × 103) in allogeneic MLR induced by MoDCs cultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. (B-C) Cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α (B), and IL-2 (C) secreted by allospecific T cells activated by MoDCs cultured with (▪) or without (■) the addition of 20 μg/mL of recombinant β2M. Values above the bars represent the concentration of the indicated cytokines. Cytometric bead array analysis was used to measure cytokine concentrations in the medium of T-cell cultures (containing T cells [Tc] and DCs at a ratio of 100:1) on day 6. (D)3H-Thymidine incorporation (cpm × 103) in autologous T-cell response induced by PPD-pulsed (squares) or unpulsed (triangles) immature MoDCs cultured with (▪,▴) or without (■,▵) the addition of 20 μg/mL recombinant β2M. Mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments are shown. *P < .05; **P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/10/10.1182_blood-2002-11-3368/4/m_h81034325004.jpeg?Expires=1765891777&Signature=aFy2lUgoQZwjvSLY44q2i9lcCAXnaC0BRHoQD-e7I691hjHQRbZJElTUtCci-kNnJKE-GvgcLFikRbak9YpVO2Qkrn9Vw~zCvdZzZhGfrKvtWVOLMhriejQk6uRvQ52p8ir-wavhvJHj2mHxYrWkYrmoyDD0VQcXvkgG48aWe2OyvtlTufpj4Ysb34MpGqTeAj~KZDi0dYuxkAzIbRoHD4BWeNprhLLBAyFprSkYNG6nKkfzKoboxUbhrtefDm8cjWOtJTxknNkhwwovyvL1DgaOrEuwXjSuS561aJezGXba~lTM0tXDrz3Scfz9gZtQrH8-N4E6KFfHNXU-~~-wqQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal