Abstract

A major end point of nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is the attainment of either mixed chimerism or full donor hematopoiesis. Because the majority of human genetic disparity is generated by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), direct measurement of SNPs should provide a robust tool for the detection and quantitation of chimerism. Using pyrosequencing, a rapid quantitative sequencing technology, we developed a SNP-based assay for hematopoietic chimerism. Based on 14 SNPs with high allele frequencies, we were able to identify at least 1 informative SNP locus in 55 patients with HLA-identical donors. The median number of informative SNPs in related pairs was 5 and in unrelated pairs was 8 (P < .0001). Assessment of hematopoietic chimerism in posttransplantation DNA was shown to be quantitative, accurate, and highly reproducible. The presence of 5% donor cells was reliably detected in replicate assays. Compared with current measures of engraftment based on identification of short tandem repeats (STRs), variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs), or microsatellite polymorphisms, this SNP-based method provides a more rapid and quantitative assessment of chimerism. A large panel of SNPs enhances the ability to identify an informative marker in almost all patient/donor pairs and also facilitates the simultaneous use of multiple markers to improve the statistical validity of chimerism measurements. The inclusion of SNPs that encode minor histocompatibility antigens or other genetic polymorphisms that may influence graft-versus-host disease or other transplantation outcomes can provide additional clinically relevant data. SNP-based assessment of chimerism is a promising technique that will assist in the analysis of outcomes following transplantation.

Introduction

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) represent a primary source of human genetic diversity, and considerable worldwide effort is now focused on the identification and cataloging of these polymorphisms in different populations.1,2 A primary objective of many of these studies is to identify SNPs that are directly responsible for disease characteristics or disease susceptibility. An alternative focus is to use SNPs as indirect markers of both simple and complex disease traits with the further use of these markers to identify the genetic elements directly involved in specific diseases.3 4 Relatively little use has been made of the ability of SNPs to distinguish individuals from one another, including those individuals who are related or closely matched for other characteristics.

After allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), distinguishing between the contributions of residual host hematopoiesis and donor hematopoiesis is critical to ensuring the appropriate use of donor lymphocyte infusions as well as assessing the impact of novel nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens on donor chimerism.5 Genotyping patient/donor pairs at SNP loci of high allelic frequency should provide useful markers for the evaluation of chimerism. The increased interest in the use of allogeneic stem cells for the therapy of nonhematologic disorders such as solid tumors,6 organ transplantation,7,8Parkinson disease,9,10 inherited diseases of childhood,11,12 and rheumatologic conditions, as well as the inherent difficulties in tracking donor cell engraftment in these settings, is likely to result in the use of these highly polymorphic markers.13 Another clinical situation in which rapid discrimination of individuals will be useful is antenatal testing to distinguish between fraternal and identical twins.14 15

In the current study we describe a panel of 14 high allele frequency SNPs that can be used to distinguish between HLA-identical patient/donor pairs. Using pyrosequencing, a rapid quantitative SNP-typing technology, we were able to identify an informative SNP locus in all related sibling pairs as well as all unrelated donor pairs tested. We also demonstrate that the measurement of chimerism by pyrosequencing is quantitative, highly accurate, and reproducible. These studies demonstrate that SNP-based analysis of hematopoietic chimerism is a promising technique that will assist in the analysis of outcomes following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Patients, materials, and methods

Sample preparation

Heparinized blood samples were obtained from 90 healthy donors and from 55 patient/donor pairs prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Approval was obtained from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute institutional review board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll/Hypaque density gradient centrifugation, cryopreserved with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, and stored in vapor phase liquid nitrogen until the time of analysis. Similar samples of bone marrow and PBMCs also were obtained from selected patients after allogeneic transplantation, and specific cellular populations were purified using MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Gladbach, Germany) or fluorescence activated cell sorting (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Cryopreserved cells were rapidly thawed, and genomic DNA was extracted from 3-10 × 106 cells using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prior to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, DNA concentration in all samples was determined by ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometry and adjusted to a concentration of 0.03 μg/μL with sterile distilled water.

PCR

PCR was performed on each sample using the primers and reaction conditions specified in Table 1. Each 50-μL reaction mixture contained 0.09 μg DNA and the following concentrations of other components: 1 × Taq Gold buffer (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA), MgCl2 (in the concentration specified in Table 1), 400 nmol each primer, 200 nmol dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP, and 2 units AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). One cycle of denaturation (95°C for 10 minutes) was performed, followed by 10 cycles of touchdown PCR (94°C for 30 seconds, 30 seconds of annealing temperature starting 10 degrees above the temperature in Table 1 and then dropping by 1 degree each successive cycle, extension at 72°C for 30 seconds) followed by 30 cycles of traditional PCR (94°C for 30 seconds, appropriate annealing temperature for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 30 seconds). SNPs 7p13, 9q22, 17q23, and 19q13 used Platinum Taq and Platinum Taq buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in place of Taq Gold.

PCR primers and reaction parameters

| SNP no. . | Chromosome location . | Forward primer . | Reverse primer . | Sequencing primer . | SNP sequence . | Magnesium concentration, mM . | Annealing temperature, °C . | Allele frequency, % (n) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8132* | 4q28 | Biotin-GGGCTCCTGGCTCTTT | CCTGTCCCTCTGTGTCAACC | TCATAGGCTCTCACT | GAGG/AAGT | 3 | 52-60 | 44 (90) |

| 2717* | 5q32 | CGCTTACCTGCCAGACTGC | Biotin-GGCCAGGACGATGAGAGA | CCACGACGTCACGCAG | CAGC/GAAA | 3 | 60 | 35 (88) |

| 2301* | 6q25 | Biotin-CGGGCTGTGCTTTCTCGT | CCGTACTCGTACGGCAGGTC | GCCCAGATACCCCAAA | CGGC/TTTT | 3 | 56 | 50 (74) |

| HA-243 | 7p13 | Biotin-GGCCGCATCTACACCTACAT | CGTTGGCCACAGCATAGAGA | CTCCTGGTAGGGGTTC | TCCG/ATGA | 2 | 58 | 26 (44) |

| 8111* | 7q36 | CCAGATGCCCAGCTAGT | Biotin-ACTCTCCAGGCACTTCAGG | CCAGCCCCTCAGATG | ATGA/GCAC | 3 | 52-60 | 33 (87) |

| 1791* | 8p22 | Biotin-TTCAAGGCTCTGTCAGTG | AAGCAAAAACAGAAGAACAA | ACAACAACAAAACCCCACAG | TAGT/CAGC | 3 | 52 | 48 (87) |

| HA-844 | 9q22 | ATTTAGAGGGGTTTGATTGTT | Biotin-AAGTTCTAATTTTTCTGGCTGT | TTGCAGTCAGCAGATCAC | ACCG/CAAC | 2 | 58 | 39 (74) |

| 8097* | 14q32 | Biotin-GAGCGGAGAGCGAAGGTGG | GTGGCGGCGGGAAC | TTGAAGGGCTGGGTA | TCAT/CTAC | 3 | 60 | 43 (67) |

| 8102* | 16q13 | TCTAACATCATGGCCGACTT | Biotin-GAAGAGTGACAGTCCCAAGG | CAAGGGCTGGTGAGTG | GTGT/CGTT | 3 | 54 | 38 (68) |

| CD3145531* | 17q23 | Biotin-TGTGAACAACAAAGAGAAAACC | GCTGTTATTCACGCCACTG | CTCACCTTCCACCAAC | CAGG/CTGT | 2 | 58 | 49 (75) |

| CD314519203* | 17q23 | Biotin-GATCTGGTCCCATCACCTATA | GGCGTGGTTGGCTCTGTTGAA | TCTCCCTCCTGTTCCT | CTAA/GCAA | 2 | 58 | 48 (74) |

| HA-1383474* | 19p13 | Biotin-TCGCTGAGGGCCTTGAGAAA | CTTGGGTCTGGCTCTGTCTT | GTGGCTCTCACCGTC | TGCG/ATGA | 2 | 58 | 37 (72) |

| 8049* | 20q13 | CGCCATGAGCAACCTG | Biotin-CGGGAGGGAAGTCAAAGTCA | CAGAGTGGACTACAT | CATT/CCTG | 3 | 60 | 48 (65) |

| 2384* | 22q13 | Biotin-GGCTGCCATTATGACCAACTA | TCCCCACTACTCTCAGAAA | GAAACTTCTTGAACCCA | TAAC/TTGG | 3 | 58 | 29 (67) |

| SNP no. . | Chromosome location . | Forward primer . | Reverse primer . | Sequencing primer . | SNP sequence . | Magnesium concentration, mM . | Annealing temperature, °C . | Allele frequency, % (n) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8132* | 4q28 | Biotin-GGGCTCCTGGCTCTTT | CCTGTCCCTCTGTGTCAACC | TCATAGGCTCTCACT | GAGG/AAGT | 3 | 52-60 | 44 (90) |

| 2717* | 5q32 | CGCTTACCTGCCAGACTGC | Biotin-GGCCAGGACGATGAGAGA | CCACGACGTCACGCAG | CAGC/GAAA | 3 | 60 | 35 (88) |

| 2301* | 6q25 | Biotin-CGGGCTGTGCTTTCTCGT | CCGTACTCGTACGGCAGGTC | GCCCAGATACCCCAAA | CGGC/TTTT | 3 | 56 | 50 (74) |

| HA-243 | 7p13 | Biotin-GGCCGCATCTACACCTACAT | CGTTGGCCACAGCATAGAGA | CTCCTGGTAGGGGTTC | TCCG/ATGA | 2 | 58 | 26 (44) |

| 8111* | 7q36 | CCAGATGCCCAGCTAGT | Biotin-ACTCTCCAGGCACTTCAGG | CCAGCCCCTCAGATG | ATGA/GCAC | 3 | 52-60 | 33 (87) |

| 1791* | 8p22 | Biotin-TTCAAGGCTCTGTCAGTG | AAGCAAAAACAGAAGAACAA | ACAACAACAAAACCCCACAG | TAGT/CAGC | 3 | 52 | 48 (87) |

| HA-844 | 9q22 | ATTTAGAGGGGTTTGATTGTT | Biotin-AAGTTCTAATTTTTCTGGCTGT | TTGCAGTCAGCAGATCAC | ACCG/CAAC | 2 | 58 | 39 (74) |

| 8097* | 14q32 | Biotin-GAGCGGAGAGCGAAGGTGG | GTGGCGGCGGGAAC | TTGAAGGGCTGGGTA | TCAT/CTAC | 3 | 60 | 43 (67) |

| 8102* | 16q13 | TCTAACATCATGGCCGACTT | Biotin-GAAGAGTGACAGTCCCAAGG | CAAGGGCTGGTGAGTG | GTGT/CGTT | 3 | 54 | 38 (68) |

| CD3145531* | 17q23 | Biotin-TGTGAACAACAAAGAGAAAACC | GCTGTTATTCACGCCACTG | CTCACCTTCCACCAAC | CAGG/CTGT | 2 | 58 | 49 (75) |

| CD314519203* | 17q23 | Biotin-GATCTGGTCCCATCACCTATA | GGCGTGGTTGGCTCTGTTGAA | TCTCCCTCCTGTTCCT | CTAA/GCAA | 2 | 58 | 48 (74) |

| HA-1383474* | 19p13 | Biotin-TCGCTGAGGGCCTTGAGAAA | CTTGGGTCTGGCTCTGTCTT | GTGGCTCTCACCGTC | TGCG/ATGA | 2 | 58 | 37 (72) |

| 8049* | 20q13 | CGCCATGAGCAACCTG | Biotin-CGGGAGGGAAGTCAAAGTCA | CAGAGTGGACTACAT | CATT/CCTG | 3 | 60 | 48 (65) |

| 2384* | 22q13 | Biotin-GGCTGCCATTATGACCAACTA | TCCCCACTACTCTCAGAAA | GAAACTTCTTGAACCCA | TAAC/TTGG | 3 | 58 | 29 (67) |

SNP numbers are from the HGBASE SNP database athttp://hgbase.cgr.ki.se/.16 For example, SNP 8132 is HGBASE:SNP000008132.

Pyrosequencing

Biotinylated single-strand DNA fragments were generated by mixing the PCR product with streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads (Dynalbeads M280; Dynal, Norway) and processing them according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pyrosequencing Sample Preparation; Pyrosequencing AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Throughout the sample preparation steps, the immobilized fragments coupled to the beads were moved using a magnetic tool (PSQ 96 Sample Preparation Tool; Pyrosequencing AB). An automated pyrosequencing instrument, PSQ96 (Pyrosequencing AB), was used to determine DNA sequence. The reaction was carried out at 28°C. The sequencing protocol used stepwise elongation of the primer strand by sequential addition of the deoxynucleoside triphosphates and the simultaneous degradation of the residual unincorporated nucleotides. As the sequencing reaction continued, extension of the cDNA strand by successful nucleotide incorporation resulted in the release of light, and the DNA sequence was determined from the peaks in the pyrogram using pyrosequencing software shown in Figure1. To examine the linearity of pyrosequencing output, genomic DNA at 0.03 μg/μL concentration from 2 individuals with disparate genotypes at 3 SNP loci were mixed in different concentrations between 0% and 100% “donor.” The mixed genomic DNA was then PCR amplified as described above, and the SNP sequence was determined by pyrosequencing. The percentage of hematopoietic chimerism was determined by the PSQ96 Allele Discrimination Software (Pyrosequencing AB). SNPs 20q13 and 8p22 were homozygous disparate. SNP 11p15 was heterozygous disparate, and in order to model human chimerism in this setting the quantitative result was mathematically converted to display the full range of chimerism possibilities. To examine the sensitivity of pyrosequencing at low levels of chimerism, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from 2 healthy individuals with homozygote disparate genotypes, and the lymphocytes were mixed in the following concentrations: 0%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5%, and 50%. Genomic DNA was then isolated from the mixed cells and pyrosequenced as described above.

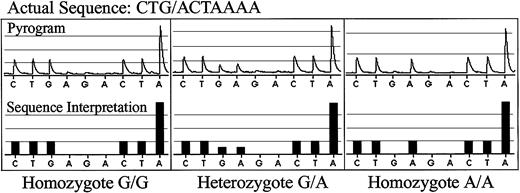

Pyrosequencing of normal donor DNA for SNP 8p22.

The actual pyrograms are shown in the top rows, and the DNA sequence interpreted by the pyrosequencing software is shown in the bottom rows. The actual sequence for SNP 8p22 is CTG/ACTAAAA. A homozygous G/G sample is shown in the left panels; a heterozygous G/A sample is shown in the middle panels; a homozygous A/A sample is shown in the right panels.

Pyrosequencing of normal donor DNA for SNP 8p22.

The actual pyrograms are shown in the top rows, and the DNA sequence interpreted by the pyrosequencing software is shown in the bottom rows. The actual sequence for SNP 8p22 is CTG/ACTAAAA. A homozygous G/G sample is shown in the left panels; a heterozygous G/A sample is shown in the middle panels; a homozygous A/A sample is shown in the right panels.

Statistical methods

The number of SNPs in the panel was determined using binomial calculations for the probability of identifying at least one informative SNP in a patient. SNPs were selected based on reported distribution of 50% in the population. SNPs selected for the panel were located on different chromosomes, and it was therefore assumed that the SNPs selected for the panel could be viewed as independent Bernoulli events, each with P = .50. A binomial model was then applied to a single patient. Under these assumptions, the minimum number of SNPs for the panel was chosen so that the probability that no SNP was informative was at most 0.01; conversely, the probability of identifying at least one informative SNP would be 0.99. For a panel of 7 SNPs, the probability of no informative SNP among 7 is 0.008.

Subsequent calculations suggested that the number of SNPs in the panel needed to be increased in order to have a high probability of finding at least one marker in each of 25, 50, or 100 patients and to allow for sibling donors and SNPs with allele frequencies < 50%. The number of SNPs required was identified as that which limited probability that no SNP was informative in a single patient to 0.004. If the probability that a SNP is informative is 0.50, 8 SNPs would be needed for the panel. If the probability of an informative SNP is 0.40 or 0.33, 11 or 14 SNPs, respectively, would be required for the panel.

If the probability of at least one informative SNP in a patient is 0.996, then the probability of finding at least one informative SNP in each of 25 patients is 0.90; in each of 50 patients is 0.82; and in each of 100 patients is 0.67. Additionally, the probability of failing to find an informative SNP in more than 1 of 25 patients is 0.005; in more than 1 of 50 patients is 0.02; and in more than 1 in 100 patients is 0.06.

Results

Highly polymorphic SNP panel

Using public SNP databases, we identified a panel of well-characterized SNPs that were known to be located on different chromosomes and had been shown to have relatively high allele frequencies in different populations.16 Several SNPs known to encode minor histocompatibility antigens (mHA) or polymorphisms thought to be associated with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) were also included in this panel. As shown in Table 1, conditions for PCR amplification of each of these 14 SNPs were optimized, and pyrosequencing was used to determine the allele frequency of these SNPs in genomic DNA from a series of anonymous healthy donors. Examples of SNP sequencing output for homozygote G/G, heterozygote A/G, and homozygote A/A individuals for SNP 8p22 are shown in Figure 1. Pyrosequencing clearly distinguished each of the 14 SNPs in our panel. As summarized in Table 1, the measured allele frequencies for these SNPs varied from 26.1% to 50% in our healthy donors, with the majority of frequencies between 35% and 50%.

Identification of informative SNP

To determine whether SNP typing could reliably distinguish between HLA-identical individuals, SNP genotyping was initially determined for 25 patient/donor pairs who underwent allogeneic HSCT, and results of this analysis are presented in Table 2. All patients were adults with a variety of hematologic malignancies. Thirteen patients had HLA-identical sibling donors, and 12 patients had HLA-identical unrelated donors. For each patient/donor pair, a SNP was defined as informative if there was any disparity between genotypes, including either homozygote/heterozygote or disparate homozygotes. Informative loci are marked as (+) and uninformative loci are marked as (−). At least 2 informative loci were found in every patient/donor pair. In patients with HLA-identical sibling donors, the number of informative loci varied from 2 to 9 (median, 5). The utility of each SNP, defined by the number of informative loci provided by that SNP, varied from 18% to 54% (mean, 39%). In patients with unrelated donors, the number of informative loci varied from 2 to 12 (median 9), and the utility of each SNP varied from 36% to 75% (mean, 60%).

Use of different SNPs in determining patient/donor differences

| Patient no. . | 4q28 . | 5q32 . | 6q25 . | 7p13 . | 7q36 . | 8p22 . | 9q22 . | 14q32 . | 16q13 . | 17q23 . | 17q23 . | 19p13 . | 20q13 . | 22q13 . | Informative SNPs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related donors | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | 6 |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | 5 |

| 3 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | 2 |

| 4 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 5 |

| 5 | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | N/A | − | − | − | + | − | − | 3 |

| 6 | − | − | − | N/A | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | 3 |

| 7 | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | 5 |

| 8 | + | N/A | − | + | − | N/A | + | − | + | + | + | − | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| 9 | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | 9 |

| 10 | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | 5 |

| 11 | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | + | − | − | 8 |

| 12 | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | 6 |

| 13 | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | 5 |

| SNP use | 3/13 | 4/12 | 5/13 | 5/12 | 6/13 | 5/12 | 5/12 | 2/11 | 6/13 | 6/13 | 7/13 | 4/13 | 5/12 | 5/12 | |

| Unrelated donors | |||||||||||||||

| 14 | + | − | + | N/A | + | + | N/A | − | + | N/A | N/A | N/A | − | − | 5 |

| 15 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | 9 |

| 16 | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | 9 |

| 17 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | N/A | − | − | 2 |

| 18 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | 11 |

| 19 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | 12 |

| 20 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | 8 |

| 21 | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | 7 |

| 22 | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | 10 |

| 23 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | 9 |

| 24 | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | 9 |

| 25 | − | + | − | N/A | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | 5 |

| SNP use | 8/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 4/11 | 9/12 | 6/12 | 8/11 | 8/12 | 6/12 | 7/11 | 8/11 | 6/10 | 4/12 | 5/12 |

| Patient no. . | 4q28 . | 5q32 . | 6q25 . | 7p13 . | 7q36 . | 8p22 . | 9q22 . | 14q32 . | 16q13 . | 17q23 . | 17q23 . | 19p13 . | 20q13 . | 22q13 . | Informative SNPs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related donors | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | 6 |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | 5 |

| 3 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | 2 |

| 4 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | 5 |

| 5 | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | N/A | − | − | − | + | − | − | 3 |

| 6 | − | − | − | N/A | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | 3 |

| 7 | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | 5 |

| 8 | + | N/A | − | + | − | N/A | + | − | + | + | + | − | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| 9 | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | 9 |

| 10 | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | 5 |

| 11 | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | + | − | − | 8 |

| 12 | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | 6 |

| 13 | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | 5 |

| SNP use | 3/13 | 4/12 | 5/13 | 5/12 | 6/13 | 5/12 | 5/12 | 2/11 | 6/13 | 6/13 | 7/13 | 4/13 | 5/12 | 5/12 | |

| Unrelated donors | |||||||||||||||

| 14 | + | − | + | N/A | + | + | N/A | − | + | N/A | N/A | N/A | − | − | 5 |

| 15 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | 9 |

| 16 | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | 9 |

| 17 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | N/A | − | − | 2 |

| 18 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | 11 |

| 19 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | 12 |

| 20 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | 8 |

| 21 | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | 7 |

| 22 | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | 10 |

| 23 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | 9 |

| 24 | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | 9 |

| 25 | − | + | − | N/A | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | 5 |

| SNP use | 8/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 4/11 | 9/12 | 6/12 | 8/11 | 8/12 | 6/12 | 7/11 | 8/11 | 6/10 | 4/12 | 5/12 |

+ indicates informative; –, uninformative; N/A, not available.

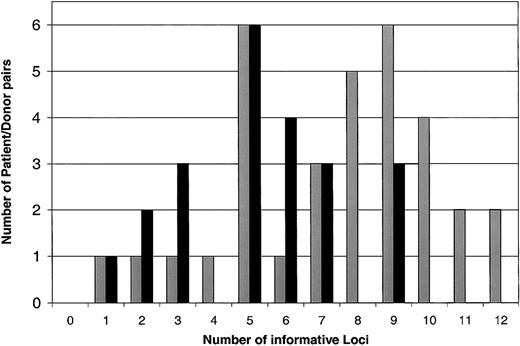

To confirm the use of this panel of 14 SNPs to reliably distinguish donor-recipient pairs, we extended our analysis to a larger panel of 55 patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT. Including the original group of 25 patients, 22 patients had HLA-identical sibling donors, and 33 had HLA-identical unrelated donors. At least one informative SNP was found in every patient-donor pair. Figure 2summarizes the cumulative number of informative loci in each patient-donor pair. As expected, the median number of informative SNPs in unrelated pairs8 was significantly higher than the median number of informative SNP in related pairs5(P < .0001 by 2-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Histogram of the number of informative SNP loci in related and unrelated patient/donor pairs.

Related donors are represented by black bars, and unrelated donors are represented by gray bars.

Histogram of the number of informative SNP loci in related and unrelated patient/donor pairs.

Related donors are represented by black bars, and unrelated donors are represented by gray bars.

Quantitative assessment of mixed chimerism

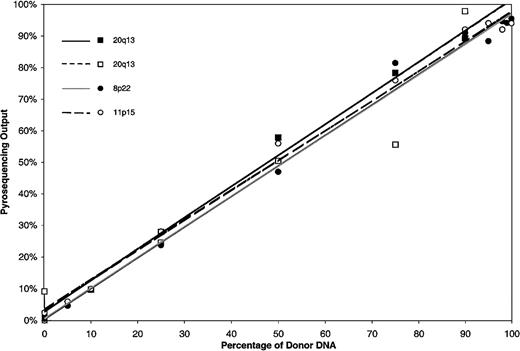

After establishing that SNP sequencing could clearly distinguish recipient from donor DNA, we undertook further experiments to determine if this method could be used to provide a quantitative assessment of mixed hematopoietic chimerism following allogeneic HSCT. Recipient and donor genomic DNA were mixed at varying concentrations, and pyrosequencing for 3 informative SNP loci was used to measure the degree of chimerism. The results of standard curves generated from analysis of genomic DNA mixtures with homozygous and heterozygous disparities are shown in Figure 3. Pyrosequencing output was highly linear across all input frequencies for all SNPs (r2 < .93). The linearity of output of a heterozygous disparity was not different from the output of a homozygous disparity.

Standard curves for quantitation of known mixtures of DNA disparate for SNPs 20q13, 8p22, and 11p15.

The quantity of donor DNA was determined by pyrosequencing known mixtures of donor and recipient DNA. SNPs 20q13 and 8p22 were homozygous disparate. The analysis for SNP 20q13 was repeated as shown in the open squares. SNP 11p15 was heterozygous disparate.

Standard curves for quantitation of known mixtures of DNA disparate for SNPs 20q13, 8p22, and 11p15.

The quantity of donor DNA was determined by pyrosequencing known mixtures of donor and recipient DNA. SNPs 20q13 and 8p22 were homozygous disparate. The analysis for SNP 20q13 was repeated as shown in the open squares. SNP 11p15 was heterozygous disparate.

Sensitivity of SNP detection at low levels of chimerism

An important element of chimerism determination is the distinction of low-level engraftment from nonengraftment. To determine the lower limit of sensitivity of the method in a clinically relevant model system, we used PBMCs from 2 healthy donors known to have a homozygotic disparity for an SNP within our panel. PBMCs were mixed at varying concentrations between 0% and 50% donor, genomic DNA was extracted from the cell mixture, and pyrosequencing of each sample was performed 5 times. Table 3 summarizes the results of this experiment. Pyrosequencing accurately measured the presence of 5% donor cells and was consistently able to detect the presence of donor cells in each of 5 replicate assays. Similar results were obtained when samples were processed at different times. However, at lower levels of chimerism, the measured level of donor cells was not consistently above background, and donor cells were not detected in all replicates.

Sensitivity of pyrosequencing at low levels of chimerism

| Donor/ recipient, % . | Donor cells detected ± SD, % . | Presence of donor SNP allele in replicate assays . |

|---|---|---|

| 50/50 | 50.4 ± 1.5 | 5/5 |

| 5/95 | 4.6 ± 3.3 | 5/5 |

| 2/98 | 0.6 ± 2.3 | 3/5 |

| 1/99 | 0 ± 2.6 | 2/5 |

| 0.5/99.5 | 0 ± 2.2 | 1/5 |

| 0/100 | 0 ± 1.5 | 0/5 |

| Donor/ recipient, % . | Donor cells detected ± SD, % . | Presence of donor SNP allele in replicate assays . |

|---|---|---|

| 50/50 | 50.4 ± 1.5 | 5/5 |

| 5/95 | 4.6 ± 3.3 | 5/5 |

| 2/98 | 0.6 ± 2.3 | 3/5 |

| 1/99 | 0 ± 2.6 | 2/5 |

| 0.5/99.5 | 0 ± 2.2 | 1/5 |

| 0/100 | 0 ± 1.5 | 0/5 |

Quantitation of hematopoietic chimerism following allogeneic stem cell transplantation

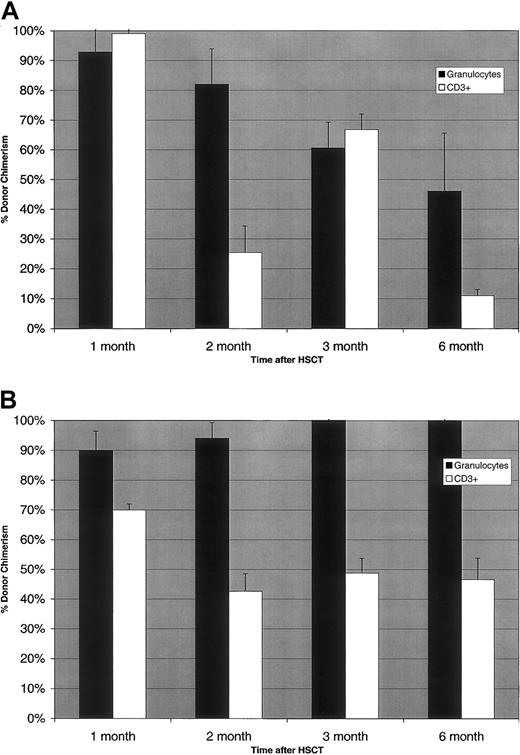

To demonstrate the feasibility of using SNP sequencing to quantify the presence of donor cells after allogeneic HSCT, we determined the level of hematopoietic chimerism in serial samples of granulocytes and CD3+ T cells purified from the peripheral blood of 2 representative patients who received peripheral blood stem cells from an HLA-identical sibling donor after nonmyeloablative conditioning. To quantify the extent of chimerism in each patient sample, 3 informative SNPs were used, and the mean level of donor chimerism was determined. As shown in Figure 4A, the first patient demonstrated > 90% engraftment of both granulocytes and CD3+ cells one month after stem cell infusion. At 2 months after transplantation, 82% of granulocytes were derived from the donor, but only 25% of T cells were donor derived. The level of donor granulocyte engraftment continued to decline at the 3-month and 6-month time points. Interestingly, donor T-cell chimerism increased at 3 months, but then declined further at 6 months after transplantation. The results of SNP chimerism analysis in a second patient (Figure 4B) demonstrated a markedly different outcome. At one month after transplantation, 90% of granulocytes were donor derived but only 70% of T cells were of donor origin. Donor granulocyte engraftment remained > 90% at 2 months, but only 42% of T cells were donor derived at this time. At subsequent time points, 100% of granulocytes continued to be of donor origin, and no residual recipient granulocytes were detected. However, only 47%-49% of T cells were donor derived at these times.

Measurement of donor chimerism following nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

(A) Patient 1: assessment of granulocyte and CD3+ cell chimerism after transplantation. (B) Patient 2: assessment of granulocyte and CD3+ cell chimerism after transplantation.

Measurement of donor chimerism following nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

(A) Patient 1: assessment of granulocyte and CD3+ cell chimerism after transplantation. (B) Patient 2: assessment of granulocyte and CD3+ cell chimerism after transplantation.

Discussion

In patients who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, outcomes of treatment are largely dependent on the stable engraftment of donor hematopoiesis and lymphopoiesis.5 Inability to establish donor hematopoiesis or loss of donor cell engraftment often indicates immunologic rejection of donor stem cells or relapse of underlying hematologic malignancy.17-20 Conversely, establishment and maintenance of complete donor hematopoiesis is associated with decreased risk of disease relapse.21,22 Patients who achieve complete donor hematopoiesis also have been shown to have a more diverse T-cell–receptor repertoire and are therefore more likely to have improved immune function following transplantation.23Patients who have stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism represent individuals who have established immunologic tolerance between donor and recipient.24 These individuals are less likely to develop graft-versus-host disease but may also be more likely to have disease relapse after transplantation.18,19,25,26 Because chimerism is such an important end point, various methods have been used to assess chimeric status after transplantation. These methods have included conventional cytogenetic analysis in cases where the sex of the recipient and donor are disparate, and molecular analysis of polymorphic tandem repeat elements in cases where sex is uninformative.5 27-32 These techniques are all relatively labor-intensive, and several days to weeks are generally required to perform these assays. As a result, it has been relatively expensive to determine levels of chimerism, which has limited the frequency of testing. Also, the statistical accuracy and reproducibility of commonly used assays have not been established.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms are recognized as the most common source of human genetic diversity with estimates of SNP frequency ranging from 1/300 to 1/1000 nucleotides.1,2 4 The normal human genome has therefore been estimated to contain between 3 and 6 × 106 SNPs, and this represents a virtually unlimited resource of molecular markers that can be used to distinguish all individuals except for monozygotic twins. To use SNP disparity as a method for analysis of chimerism, we identified a panel of high allele frequency SNPs on different chromosomes from the HGBase database. Prior to assembling this panel, we calculated that 7 SNPs of 50% allele frequency would provide a 99% probability of identifying at least a single informative SNP locus for HLA-identical sibling/patient pairs. Similarly, a panel of 7 SNPs with 50% allele frequency would be sufficient to identify a single informative locus in 99.2% of unrelated pairs. If the allele frequencies of SNPs in the panel were below 50%, the size of the panel would have to be increased to maintain this high likelihood of identifying an informative locus. These results were confirmed experimentally with our panel of 14 SNPs that were tested on 55 patient/donor pairs. Using this panel we determined that either 11 or 6 SNPs were sufficient to provide 99.6% probability of identifying at least one informative locus in related and unrelated pairs, respectively. Expanding the SNP panel beyond this minimal number further increases the probability of identifying a single informative locus in virtually all patient/donor pairs. More importantly, expanding the SNP panel facilitates the identification of multiple informative loci in each patient/donor pair. Thus, our panel of 14 SNPs provided one informative locus in 55 of 55 patient/donor pairs and at least 2 informative loci in 53 of 55 patient/donor pairs. Further expansion of the SNP panel to 18 would provide a 99.6% probability of identifying at least 3 informative loci in related patient/donor pairs. The use of multiple independent SNP loci improves the accuracy and statistical validity of SNP sequence analysis for quantifying the degree of chimerism in different cellular populations following transplantation. Because our SNP panel is currently optimized for the North American population, it is likely to require modification for use in other populations. Importantly, high allele frequency SNPs are being identified for all populations, and additional SNPs for use in different patient groups easily can be added.

The analysis of engraftment following HSCT requires the quantitative assessment of chimerism in addition to the qualitative ability to detect the presence of allogeneic cells. Gel electrophoresis methods use densitometric analysis of the PCR product to provide a quantitative assessment of chimerism. Recent reports also have described the use of quantitative real-time PCR for STR elements and SNPs to quantify chimerism.32,33 When used to assess STR elements, real-time PCR improves the sensitivity of chimerism detection, but the accuracy of measurement is reduced when levels of mixed chimerism are above 10%.32 In contrast, quantitative real-time PCR to assess DNA mixtures of homozygous disparate SNPs appeared to have less sensitivity than electrophoretic methods.33 These limitations led us to choose pyrosequencing as our analytic procedure for SNP genotyping. Analysis of defined mixtures of different DNAs as well as patient samples confirmed the accuracy of this method for quantifying the relative contributions of donor and recipient DNA in mixed cellular populations. As shown in Figure 1, the interpretation of each individual genotype also is determined in the context of neighboring nucleotides. Unlike gel-based and real-time PCR techniques, this nucleotide sequence provides confirmatory evidence that the correct SNP has been detected. In conjunction with the ability to identify multiple informative SNP loci, this enhances the accuracy and reproducibility of this method for quantitative assessment of chimerism in unknown samples. One additional advantage of this method is the ability to rapidly identify informative loci and analyze relatively large numbers of samples. Once PCR has been completed, the determination of 96 different SNP genotypes can be performed in < 2 hours. Even without further automation, this method now can be used to determine chimerism status on the same day that the patient sample has been obtained.

An additional important element in the determination of transplantation outcome is the detection of low levels of donor engraftment. The lower limit of sensitivity of the pyrosequencing method appears to be 5%. Detection of 1% to 3% donor cells is possible, but testing of multiple replicate samples would be necessary to achieve this marginally improved level of sensitivity. This level of sensitivity is identical to electrophoretic methods, which can detect 1% to 5% of donor cells.28 34 Although the clinical significance of microchimerism below the 5% level has not been established, it may be possible to further enhance the sensitivity of this method by additionally optimizing PCR conditions and by using a larger quantity of PCR product in the sequencing reaction. However, it appears unlikely that further improvements such as these would increase the sensitivity below 1% without significant changes in the sensitivity of the pyrosequencing method itself.

In addition to SNPs that were selected only on the basis of high allele frequency, our panel also includes 5 SNPs that encode known minor histocompatibility antigens (mHAs) or polymorphisms that may influence GVHD. Minor histocompatibility antigens are peptides derived from normal cellular proteins that are presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or class II molecules expressed by recipient cells.35,36 Recipient T cells are tolerant to these self-antigens, but donor T cells are capable of responding to these antigens if the peptides include amino acid polymorphisms not present in the donor.37 The immunogenicity of mHAs is most often due to the presence of coding SNPs that distinguish recipient from donor cells.38,39 SNPs encoding these known mHAs all had relatively high allele frequencies and were well suited for detection of chimerism. However, in these instances disparities of SNPs that encode mHAs may result also in immunologic disparity that can result in GVHD.40 Other SNPs that affect cytokine expression levels also may influence GVHD and also are easily assessed by our system. In our population we used the primers for interleukin-6-174 (IL-6-174) (G/C) SNP41 as well as the IL-2-330 (T/G) SNP.42 In our population the allele frequencies for these were 40% and 60%, respectively. Compared with STR-based methods, the flexibility of this system allows the determination of chimerism in parallel with functionally significant genetic polymorphisms. Thus, the inclusion of SNPs that define mHAs will provide additional information that may be relevant to the clinical outcomes of allogeneic transplantation.

Dr Soiffer is a Clinical Research Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 29, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1365.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI29530 and the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Research Fund.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Jerome Ritz, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail:jerome_ritz@dfci.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal