We have previously identified α-defensin in association with medial smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in human coronary arteries. In the present paper we report that α-defensin, at concentrations below those found in pathological conditions, inhibits phenylephrine (PE)–induced contraction of rat aortic rings. Addition of 1 μM α-defensin increased the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of PE on denuded aortic rings from 32 to 630 nM. The effect of α-defensin was dose dependent and saturable, with a half-maximal effect at 1 μM. α-Defensin binds to human umbilical vein SMCs in a specific manner. The presence of 1 μM α-defensin inhibited the PE-mediated Ca++ mobilization in SMCs by more than 80%. The inhibitory effect of α-defensin on contraction of aortic rings and Ca++ mobilization was completely abolished by anti–low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein/α2-macroglobulin receptor (LRP) antibodies as well as by the antagonist receptor-associated protein (RAP). α-Defensin binds directly to isolated LRP in a specific and dose-dependent manner; the binding was inhibited by RAP as well as by anti-LRP antibodies. α-Defensin is internalized by SMCs and interacts with 2 intracellular subtypes of protein kinase C (PKC) involved in muscle contraction, α and β. RAP and anti-LRP antibodies inhibited the binding and internalization of α-defensin by SMCs and its interaction with intracellular PKCs. These observations suggest that binding of α-defensin to LRP expressed in SMCs leads to its internalization; internalized α-defensin binds to PKC and inhibits its enzymatic activity, leading to decreased Ca++mobilization and SMC contraction in response to PE.

Introduction

Inflammation has been implicated as a risk factor in the development of atherosclerosis (reviewed by Tracy1); α-defensins may provide one link between the 2 processes. α-Defensins are composed of 3 closely related gene products, also referred to as human neutrophil peptides 1-3 (HNPs-1-3). α-Defensins are cationic peptides composed of 29 to 32 amino acids arranged in 3 antiparallel β sheets that are stabilized by 3 canonical intramolecular disulfide bonds.2,3α-Defensins are normally sequestered in the granules of neutrophils, where they constitute 5% of the total cellular protein and are involved in the intracellular killing of prokaryotic organisms.4 However, α-defensins are released extracellularly during inflammatory reactions, which could exert deleterious effects on host cells. Increased plasma concentrations of α-defensins have been described in several inflammatory diseases. For example, defensin concentration approaches 30 μM in the blood of patients with bacterial septicemia or meningitis.5 Even higher levels are found in sputum from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients6 or in pleural fluid in patients with empyema.7

In previous studies, we reported that α-defensins inhibit the fibrinolytic system,8 a process that favors the development of atherosclerotic lesions.9,10 We also observed that α-defensins regulate lipoprotein metabolism by stimulating the binding of lipoprotein (a) (Lp(a))11 and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)12 to vascular cells and cell matrix.13 The biologic relevance of these observations is supported by the presence of α-defensins in normal-appearing adult epicardial coronary arteries as well as in vessels with minimal intimal thickening; staining was particularly intense in and around vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs).14 α-Defensins were also found in association with intimal and medial SMCs in atherosclerotic carotid arteries.11

Considering that α-defensins are found in human blood vessels, in and around vascular SMCs, we asked if α-defensins had any effect on SMC activity that may be involved in the evolution of vascular disease. The results of the present study indicate that α-defensins inhibit the contraction of SMCs in aortic rings. We show that low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein/α2-macroglobulin receptor (LRP) mediates the internalization of α-defensin. Internalized α-defensin binds to protein kinase C (PKC) α and β, inhibiting their activity and causing decreased Ca++ mobilization.

Materials and methods

Materials

α-Defensin (human neutrophil peptide 3) and murine monoclonal antidefensin antibodies were the kind gift from Dr T. Ganz (Department of Medicine, Univiversity of California at Los Angeles) and were prepared and characterized as previously described15; the protein migrated as a single band on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). LRP-antagonist receptor-associated protein (rRAP), soluble LRP, and anti-LRP were kindly provided by Dr D. Strickland (American Red Cross, Rockville, MD). Anti-LRP antibodies were also purchased from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT). Human umbilical vein vascular SMCs were the kind gift from Dr D. Cines (Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania) and were prepared as described by Grobmyer et al.16 Protein G–agarose was purchased from GIBCO (Bethesda, MD). Rabbit anti-PKC antibodies and calphostin C were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Contraction response

Experiments were performed as described by Haj-Yehia et al.17 Briefly, male Sprague Dawley rats (250-275 g) were killed by exsanguination. The thoracic aorta was removed, dissected free of fat and connective tissue, and cut into transverse rings 5 mm in length.18 19 The rings were gently rotated on a stainless steel rod to remove the endothelium (denuded aorta). The tissues were kept in an oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) solution of Krebs-Henseleit (KH) buffer (144 mM NaCl, 5.9 mM KCl, 1.6 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, and 11.1 mM D-glucose). The rings were mounted to record isometric tension in a 10-mL bath containing KH solution under continuous aeration. The rings were equilibrated for 1.5 hours at 37°C and maintained under a resting tension of 2 g throughout the experiment. Each aortic ring was then contracted by adding phenylephrine (PE) in stepwise increments (from 10−10 M to 10−5 M). In other experiments, various concentrations of α-defensin were added 5 minutes before adding PE. In each experiment, rings exposed to KH buffer alone were analyzed in parallel. Isometric tension was measured with a force displacement transducer and recorded online using a computerized system (ExperimentiaÆ, Budapest, Hungary). The maximal contraction of the rings (100%) was determined by adding 20 to 40 mM KCl.

The half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) was calculated by measuring the response of aortic rings (y-axis) to increasing concentrations of PE (x-axis). The lines that intersect with the y- and x-axes were drawn to determine the concentration of PE that induces 50% of its maximal effect. Each EC50 was calculated as the mean ± SD of 3 separate experiments.

Binding and internalization of α-defensin

125I-α-defensin was radiolabeled and characterized as described previously.20 Cells were grown to confluence in 48-well Falcon multiwell tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, NJ) to a final density of approximately 5 × 104 cells per well in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Bet Haemek Israel) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). The cells were prechilled to 4°C for 30 minutes and washed twice with KH buffer. The cells were then incubated with KH buffer containing varying concentrations of125I-defensin for 1 hour at 4°C. Washing the cells 4 times with binding buffer to remove unbound ligand terminated the incubation. Radiolabeled ligand bound to the cell surface was released by adding 50 μM glycine HCl, pH 2.8, as described by Higazi et al.21 Nonspecific binding was determined by measuring cell-associated radioactivity in the presence of 100 μM unlabeled α-defensin. Specific binding was defined as the difference between total and nonspecific binding.

In one set of experiments, after the cells were incubated with125I-defensin for 1 hour at 4°C and washed 4 times with binding buffer to remove unbound ligand, the cells were warmed to 37°C for another hour, and radiolabeled ligand bound to the cell surface was released with glycine HCl, pH 2.8. After releasing cell surface–bound ligand, internalized α-defensin was determined by solubilizing the cells with 0.1 N NaOH and measuring the cell-associated radioactivity.

To determine the incorporation of radiolabeled α-defensin into isolated aortic rings, denuded aortic rings were incubated in KH buffer with 1.5 μM 125I-defensin (the concentration that gave 50% of the maximal inhibitory effect) at 37°C for 30 minutes in the absence or presence of 100 μM unlabeled α-defensin. The incubation was terminated by washing the aortic rings 4 times with binding buffer to remove unbound ligand. Radiolabeled ligand incorporated into the aortic rings was measured using a γ-counter. Nonspecific binding was determined by measuring cell-associated radioactivity in the presence of 100 μM unlabeled α-defensin. When indicated, 100 nM anti-LRP antibodies, 20 nM rRAP, or 100 nM anti-LDL receptor antibodies (as irrelevant antibodies) were added 5 minutes before the radiolabeled α-defensin.

Binding of α-defensin to isolated LRP

Binding of 125I-defensin to LRP-coated wells was determined as described by Higazi et al.21 Varying concentrations of 125I-defensin were added to LRP-coated wells in the presence or absence of excess unlabeled α-defensin, and the total and specific binding was measured as in the previous paragraph. Specific binding was defined as the difference between total and nonspecific binding.

Measurement of intracellular calcium

The effect of α-defensin on PE-induced intracellular calcium (Ca++i) in human umbilical vein SMCs was measured as described by Haj-Yehia et al,17 Tozawa et al,22 and Ikeda et al.23 SMCs were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in media in the presence or absence of 1 μM fluo-3 acetomethyl ester (Fluo-3; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).24 The cells were washed 3 times with Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate solution that contained 2 μM Ca++. One milliliter of Ca++-containing medium was then added to each well. Baseline pictures were taken at 490 nm excitation and 520 nm emission using a Hamamatsu ORCA-100 cooled CCD digital camera and an inverted Nikon-TMD Diaphot epifluorescence microscope. PE (0.1 μM) was then added, and Fluo-3 emission was measured at 5 minutes. α-Defensin had no effect on dye uptake.

To quantify calcium concentration, at least 5 individual cells in 3 or more plates for each condition were outlined, the average pixel intensity per cell was calculated, and the background emission was subtracted. Dye loading was uniform among plates and cells and did not contribute to these analyses. The mean fluorescence pixel intensity in control cells was designated as 100%. Images representative of a minimum of 3 experiments are shown.

In the set of experiments used to determine the rapid transient peak in intracellular Ca++, a 1-mM stock solution of Fluo-4 (Molecular Probes) was mixed with an equal volume of a 20% (wt/vol) solution of the nonionic detergent pluronic acid F-127 in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Molecular Probes) and then added to washed cells to a final concentration of 5 μM. Cells were incubated with Fluo-4 for 20 minutes at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any dye that was nonspecifically associated with the cell membrane and then incubated for another 30 minutes to allow complete de-esterification of intracellular acetoxymethyl (AM) esters.

The Fluo-4 fluorescence was determined by employing a 20 ×/0.6 plan Neofluor lens (Zeiss) in a Zeiss LSM 410 confocal system with an Axiovert 135 inverted microscope. Fluorescence excitation was induced by an argon ion laser with a 515-nm emission filter and measured every 10 seconds for 8 minutes.

Several random fields for each experiment were taken and scored. Confocal TIF images were transferred to a Zeiss imaging workstation for fluorescence intensity analysis. The results were expressed numerically in terms of arbitrary fluorescence units of 0 to 250, where white is the highest amount of fluorescence above background per area.

Radiolabeled Ca++ uptake

Experiments were performed as previously described.25 Human umbilical vein SMCs were grown in 60-mm dishes. 45Ca++ uptake was determined by overlaying the cells with KH buffer containing 25 μM45Ca++ at 37°C. PE (0.1 μM) was then added. When indicated, 1 μM α-defensin, alone or together with rRAP or anti-LRP antibodies, was added 5 minutes before PE. Fifteen minute after adding PE with or without the additives, the cells were washed to remove free 45Ca++, solubilized, and45Ca++ determined.

Immunoprecipitation

A total of 108 human SMCs were incubated in KH buffer with 1 μM 125I-α-defensin at 37°C for 30 minutes in the presence or absence of anti-LRP antibodies (100 nM) or irrelevant immunoglobulin G IgG (100 nM). In another set of experiments the cells were incubated with 125I-α-defensin and a 50-fold excess of unlabeled α-defensin. Washing the cells 4 times with binding buffer to remove unbound ligand terminated the incubation. The cells were then lysed by adding 1 mL of 10 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) HCl buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), and 1% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes. The mixture was added to 3 mL protein G–agarose in KH buffer containing 100 nM anti-PKC antibodies or irrelevant antibodies and incubated for 6 hours at 4°C. The beads were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was decanted. The precipitate was washed 4 times with KH buffer, and the radioactivity precipitated by protein G–agarose was measured. Nonspecific binding of α-defensin was determined by measuring the precipitation of 125I-α-defensin in the presence of an excess of unlabeled α-defensin or when irrelevant IgG was used instead of anti-PKC antibodies. Both methods used to determine nonspecific binding gave very close results.

Confocal microscopy

Cells grown on coverslips were incubated in DMEM containing 1 μM defensin and supplemented with 10% FCS for 30 minutes at 37°C. The cells were washed 3 times with PBS, fixed for 10 minutes with 4% formaldehyde in PBS, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS–bovine serum albumin (BSA) buffer for 3 minutes. The coverslips were overlaid for 20 minutes with 2% normal horse serum and then incubated for 40 minutes with antidefensin antibodies diluted 1:500 with PBS. After 4 washes with PBS, the cells were stained for 40 minutes with Alexo 488–labeled goat antirabbit serum (Molecular Probes), washed 4 times with PBS, and mounted in 80% glycerol–20% PBS supplemented with 3% DABCO (1,4-diazabicyclo-[2,2]-octane) as antibleaching agent. No staining was seen when either antidefensin or the secondary antibody was omitted.

Confocal microscopy was performed using a Zeiss LSM 410 confocal laser scanning system attached to the Zeiss Axiovert 135M inverted microscope 40 ×/1.3 plain oil immersion lens. The system was equipped with a 25-mW argon laser (488-nm excitation line with 515-nm low-pass barrier filter) for the excitation of Alexa 488 green fluorescence. The differential interference contrast (DIC) images according to Nomarski were collected simultaneously using a transmitted light detector. Autofluorescence of the specimen was set to background level. To reduce the visual noise, all optical sections were performed in the fast line-scan acquisition mode (512 pixels per line) by the averaging of 8 images before the final image was produced on the monitor. In each experiment, background level, exciting light intensity, photomultiplier, imaging filters, aperture (pinhole) contrast, and electronic zoom size were monitored at the same level. Confocal images were converted to a TIF format and transferred to a Zeiss imaging workstation to provide pseudocolor representation. Z series of optical sections were acquired at 0.7-μm intervals from the surface through the vertical axis of the specimen, assembled in an image processor, and projected on a monitor into a single image using image analysis software (Zeiss). The display of the images in color-coded mode (depth coding) was used to determine the depth at which the features of interest lay.

All experiments were performed in triplicate and were repeated a minimum of 3 times. All data are presented as mean ± SD of the 3 experiments.

Results

Because α-defensin is present in human blood vessels11 in and around arterial SMCs,14 it was of interest to see whether α-defensin affects activity of vascular SMCs. To address this question, we examined the effect of α-defensin on aortic rings denuded of endothelium. Figure1A shows that at concentrations up to 10 μM α-defensin alone had no effect on the contraction of rat aortic rings. However, the presence of 1 μM α-defensin inhibited the phenylephrine (PE)–induced contraction of denuded rat aortic rings (Figure 1A); 1 μM α-defensin increased the EC50 of PE almost 20-fold, from 32 to 630 nM (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 1B, the effect of α-defensin on PE-induced contraction was completely abolished by antidefensin antibodies. The inhibitory effect of α-defensin was dose dependent and saturable, with a half-maximal effect observed at a concentration of about 1 μM (not shown).

Effect of α-defensin on contraction of aortic rings.

(A) The effect of increasing concentrations of α-defensin on the contraction of denuded rat aortic rings (▴). The effect of increasing concentrations of PE was measured in the absence (■) or presence (▪) of 1 μM α-defensin. (B) The effect of anti–α-defensin antibodies: EC50 of PE was determined in the absence (Cont) or presence of 1 μM α-defensin (Def), α-defensin and specific anti–α-defensin antibody (Def+sAb), or α-defensin and irrelevant antibodies (Def+irAb). All experiments, unless otherwise indicated, were performed in triplicate and were repeated at least 3 times. In this and in all graphs, the data are presented as means ± SD of 3 experiments.

Effect of α-defensin on contraction of aortic rings.

(A) The effect of increasing concentrations of α-defensin on the contraction of denuded rat aortic rings (▴). The effect of increasing concentrations of PE was measured in the absence (■) or presence (▪) of 1 μM α-defensin. (B) The effect of anti–α-defensin antibodies: EC50 of PE was determined in the absence (Cont) or presence of 1 μM α-defensin (Def), α-defensin and specific anti–α-defensin antibody (Def+sAb), or α-defensin and irrelevant antibodies (Def+irAb). All experiments, unless otherwise indicated, were performed in triplicate and were repeated at least 3 times. In this and in all graphs, the data are presented as means ± SD of 3 experiments.

To examine the reversibility of the inhibitory effect of α-defensin, we incubated aortic rings with or without 1 μM α-defensin for 30 minutes. After the incubation, the rings were washed and the response to PE was determined at different time points. Figure 2 shows that the inhibitory effect of α-defensin began to decrease after 30 minutes of washing and was undetectable after 120 minutes.

The reversibility of the inhibitory effect of α-defensin.

Aortic rings were incubated with (▪) or without (▴) 1 μM α-defensin for 30 minutes. After washing, the response to PE was determined immediately (0 minute) or after 15, 30, 60, 75, or 120 minutes. The EC50 was determined as described in “Materials and methods.”

The reversibility of the inhibitory effect of α-defensin.

Aortic rings were incubated with (▪) or without (▴) 1 μM α-defensin for 30 minutes. After washing, the response to PE was determined immediately (0 minute) or after 15, 30, 60, 75, or 120 minutes. The EC50 was determined as described in “Materials and methods.”

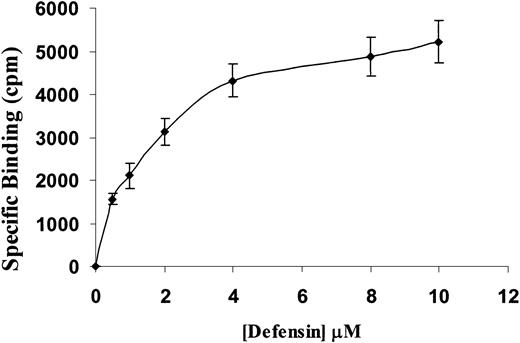

To elucidate the mechanism through which α-defensin inhibited SMCs contractility, we examined the binding of α-defensin to SMCs. Figure3 shows that 125I-defensin binds in a dose-dependent, saturable, and specific fashion to human vascular SMCs, with a calculated dissociation constant (Kd) of about 1.5 μM, close to the concentration that induced half-maximal inhibition of SMC contraction.

Specific binding of 125I-defensin to SMCs.

Human umbilical vein SMCs were incubated with the indicated concentrations of 125I-α-defensin in the presence or absence of 100 μM unlabeled α-defensin. Specific binding was determined as described in “Materials and methods.”

Specific binding of 125I-defensin to SMCs.

Human umbilical vein SMCs were incubated with the indicated concentrations of 125I-α-defensin in the presence or absence of 100 μM unlabeled α-defensin. Specific binding was determined as described in “Materials and methods.”

Studies were then performed to identify the receptor involved in the α-defensin–induced inhibitory effect. Although we have previously observed12 that α-defensin binds to the LDL receptor (LDL-R), anti–LDL-R antibodies had no effect on α-defensin–induced inhibition of aortic contractility (Figure4). We then turned our attention to the low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein/α2-macroglobulin receptor (LRP), another member of the LDL-R family26,27; Bacskai et al reported that binding of α2-macroglobulin to LRP increased Ca++ influx into cultured neurons.28Therefore, we examined the effect of LRP inhibitors on the activity of α-defensin. Figure 4 shows that the effect of α-defensin on contractility of aortic ring was inhibited by anti-LRP antibodies and was abolished by the LRP-antagonist receptor-associated protein (rRAP).29 30

Role of LRP in α-defensin–mediated vasocontractility.

The contraction of aortic rings was induced by PE in the presence of 1 μM α-defensin (Def), α-defensin and 100 nM anti-LDL receptor antibody (anti-LDLR), α-defensin and 20 nM anti-LRP antibody (anti-LRP), α-defensin and 20 nM rRAP (rRAP), or PE with no additives (Cont).

Role of LRP in α-defensin–mediated vasocontractility.

The contraction of aortic rings was induced by PE in the presence of 1 μM α-defensin (Def), α-defensin and 100 nM anti-LDL receptor antibody (anti-LDLR), α-defensin and 20 nM anti-LRP antibody (anti-LRP), α-defensin and 20 nM rRAP (rRAP), or PE with no additives (Cont).

The interaction between LRP and α-defensin was examined in further detail: Figure 5A shows that125I-α-defensin bound specifically to LRP-coated wells with half-maximal binding at about 2 μM. Binding of α-defensin to LRP was inhibited by rRAP as well as by anti-LRP but not by irrelevant antibodies (Figure 5B).

Binding of radiolabeled α-defensin to isolated LRP.

(A) Binding of 125I-α-defensin to LRP-coated wells. Varying concentrations of 125I-α-defensin were added to LRP-coated wells in the presence or absence of excess unlabeled α-defensin, and the total (■) and specific (▪) binding were measured. (B) Inhibition of α-defensin binding by rRAP and anti-LRP antibodies. 125I-defensin (2 μM) was added to LRP-coated wells in the presence of medium alone (Cont) or medium supplemented with 20 nM rRAP (rRAP), anti-LRP antibody (anti-LRP), or irrelevant antibody (irAntib).

Binding of radiolabeled α-defensin to isolated LRP.

(A) Binding of 125I-α-defensin to LRP-coated wells. Varying concentrations of 125I-α-defensin were added to LRP-coated wells in the presence or absence of excess unlabeled α-defensin, and the total (■) and specific (▪) binding were measured. (B) Inhibition of α-defensin binding by rRAP and anti-LRP antibodies. 125I-defensin (2 μM) was added to LRP-coated wells in the presence of medium alone (Cont) or medium supplemented with 20 nM rRAP (rRAP), anti-LRP antibody (anti-LRP), or irrelevant antibody (irAntib).

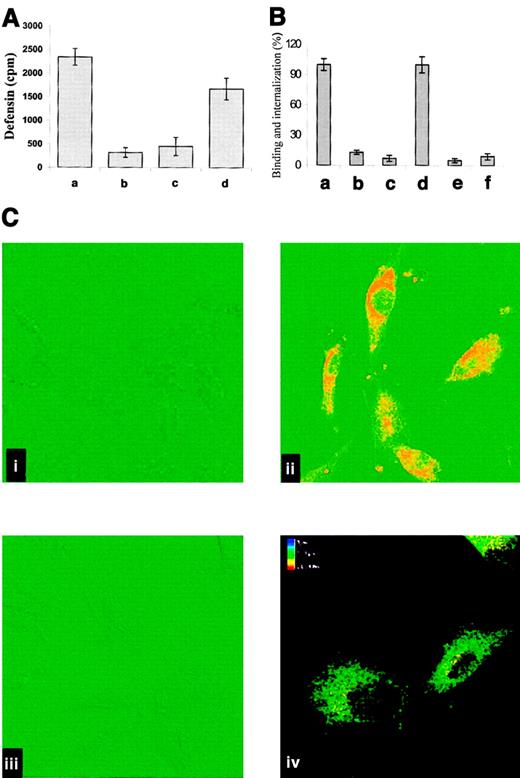

On the basis of the known capacity of LRP to mediate the internalization of diverse ligands and to characterize the interaction between α-defensin and cell-associated LRP, we asked whether α-defensin is internalized by SMCs. To address this question, we first examined the capacity of cell-bound α-defensin to be internalized. SMCs were incubated with 125I-defensin at 4°C for 30 minutes, and the cells were washed to remove unbound α-defensin and then warmed to 37°C. Under these conditions most of the bound α-defensin was internalized (Figure6A). Figure 6B shows that RAP and anti-LRP inhibited the binding and internalization of α-defensin by SMCs, whereas irrelevant IgG had no effect on either parameter (not shown). Anti-LRP antibodies (Figure 6C) also inhibited the binding and internalization of α-defensin, as seen directly by confocal microscopy; again, irrelevant antibodies had no effect (not shown).

Internalization of α-defensin by SMCs.

(A) Human umbilical vein SMCs were incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with 2 μM 125I-α-defensin. Washing of the cells terminated incubation. Bound 125I-defensin released immediately from the surface of SMCs (a) or after subsequent warming to 37°C for 30 minutes (b2). Internalized 125I-α-defensin at 4°C (c) or 37°C (d). (B) The role of LRP in binding and internalization of α-defensin by SMCs. Experiments were performed as in panel A. Binding (a,b,c) and internalization (d,e,f) of125I-defensin were determined at 37°C in the absence of additives (a,d) or in the presence of 20 nM anti-LRP antibody (b,e) or 20 nM rRAP (c,f). (C) Confocal fluorescence images of defensin binding and internalization by SMCs. Alexo 488–labeled antigens are depicted in red, and DIC images are shown in green. (i) SMCs incubated with antidefensin IgG (rabbit), followed by labeled goat antirabbit IgG, in the absence of α-defensin. (ii) SMCs incubated with 1 μM α-defensin for 30 minutes and later treated as in panel i. (iii) Cells preincubated for 10 minutes with anti-LRP antibodies (20 nM) before addition of 1 μM α-defensin and later treated as in panel B. (iv) Image reconstruction of 16 single sections presented in the color-coding scale. The upper section is shown in red, and the bottom section is shown in blue. Original magnification × 400.

Internalization of α-defensin by SMCs.

(A) Human umbilical vein SMCs were incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with 2 μM 125I-α-defensin. Washing of the cells terminated incubation. Bound 125I-defensin released immediately from the surface of SMCs (a) or after subsequent warming to 37°C for 30 minutes (b2). Internalized 125I-α-defensin at 4°C (c) or 37°C (d). (B) The role of LRP in binding and internalization of α-defensin by SMCs. Experiments were performed as in panel A. Binding (a,b,c) and internalization (d,e,f) of125I-defensin were determined at 37°C in the absence of additives (a,d) or in the presence of 20 nM anti-LRP antibody (b,e) or 20 nM rRAP (c,f). (C) Confocal fluorescence images of defensin binding and internalization by SMCs. Alexo 488–labeled antigens are depicted in red, and DIC images are shown in green. (i) SMCs incubated with antidefensin IgG (rabbit), followed by labeled goat antirabbit IgG, in the absence of α-defensin. (ii) SMCs incubated with 1 μM α-defensin for 30 minutes and later treated as in panel i. (iii) Cells preincubated for 10 minutes with anti-LRP antibodies (20 nM) before addition of 1 μM α-defensin and later treated as in panel B. (iv) Image reconstruction of 16 single sections presented in the color-coding scale. The upper section is shown in red, and the bottom section is shown in blue. Original magnification × 400.

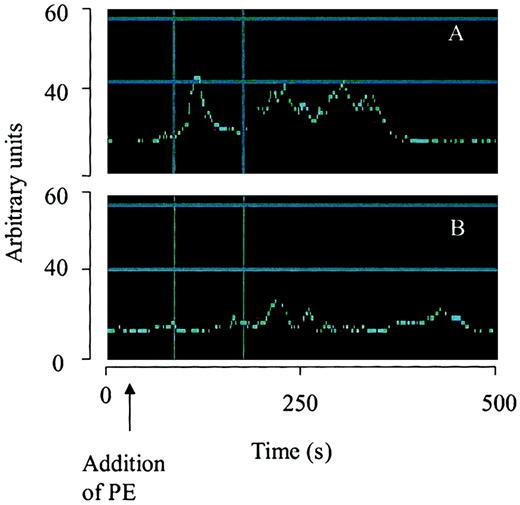

To investigate the mechanism by which the interaction of α-defensin with LRP inhibits SMC contractility, we examined the effect of α-defensin on PE-induced Ca++ mobilization. As seen in Figure 7A, 100 nM PE induced a 162% increase in intracellular Ca++, which was markedly inhibited by 1 μM α-defensin. Moreover, 1 μM α-defensin almost completely inhibited PE-induced 45Ca++internalization (Figure 7B). We then examined the involvement of LRP in the α-defensin effect on Ca++ mobilization. Figure 7B shows that rRAP and anti-LRP antibodies completely inhibited the effect of α-defensin, whereas irrelevant antibodies had no effect (not shown). Phenylephrine stimulation produces a rapid transient peak in intracellular Ca++. To examine the effect of α-defensin on this transient peak of intracellular Ca++, we determined the time course of the increase in Ca++ concentration using consecutive confocal microscopy images. Figure8A shows that PE induced the appearance of a transient peak, followed by more permanent ones, and that α-defensin inhibited the appearance of both peaks of Ca++(Figure 8B). In the experiment shown in Figure 8, α-defensin was added immediately after PE. In other experiments, α-defensin was added before PE and the same result was obtained.

Effect of α-defensin on PE-induced Ca++mobilization in human umbilical vein SMCs.

(A) SMCs were incubated in media with no additives (Cont.), or in the presence of 100 nM PE (PE) or 100 nM PE and 1 μM α-defensin (PE+Defensin) and photographed at 490 nm excitation and 520 nm emission. Original magnification × 40. (B) SMCs were incubated with buffer containing 45Ca++and 100 nM PE (PE); 100 nM PE and 1 μM α-defensin (PE+Def.);45Ca++ with no additives (cont); 100 nM PE, 1 μM defensin, and 20 nM rRAP (PE+Def.+rRAP); or 100 nM anti-LRP antibodies instead of rRAP (PE+Def.+Ab.).

Effect of α-defensin on PE-induced Ca++mobilization in human umbilical vein SMCs.

(A) SMCs were incubated in media with no additives (Cont.), or in the presence of 100 nM PE (PE) or 100 nM PE and 1 μM α-defensin (PE+Defensin) and photographed at 490 nm excitation and 520 nm emission. Original magnification × 40. (B) SMCs were incubated with buffer containing 45Ca++and 100 nM PE (PE); 100 nM PE and 1 μM α-defensin (PE+Def.);45Ca++ with no additives (cont); 100 nM PE, 1 μM defensin, and 20 nM rRAP (PE+Def.+rRAP); or 100 nM anti-LRP antibodies instead of rRAP (PE+Def.+Ab.).

Effect of α-defensin on temporal changes of intracellular Ca++.

The change of fluorescence over time from selected areas containing the same number of cells is illustrated using arbitrary units. Cells were treated with PE (100 nM) alone (A) or 100 nM PE with 2 μM α-defensin (B).

Effect of α-defensin on temporal changes of intracellular Ca++.

The change of fluorescence over time from selected areas containing the same number of cells is illustrated using arbitrary units. Cells were treated with PE (100 nM) alone (A) or 100 nM PE with 2 μM α-defensin (B).

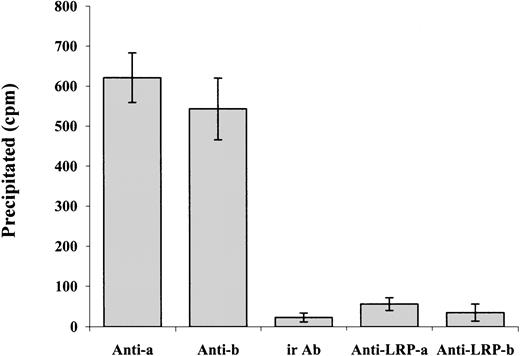

Our data show that α-defensin exerts its inhibitory effect on PE-induced SMC contraction and Ca++ mobilization by interacting with LRP. At the same time, α-defensin alone has no effect on cell contraction. These data suggest that α-defensin may inhibit some of the mechanisms that are activated during SMC contraction. Charp et al found that α-defensin inhibits the activity of PKC.31 It is widely accepted that PKC plays an important role in the contraction of SMCs; in the case of cerebral vasospasm, PKC is considered to have a significant role by phosphorylating various ion channels and augmenting voltage-dependent Ca++ channels, which leads to vessel contraction.32 PKC has also been reported to enhance CaV1.2b channel currents in various SMC preparations.33-37 A number of different agonists, including norepinephrine, endothelin, angiotensin II, and serotonin, have been suggested to stimulate CaV1.2b channels via a PKC-dependent mechanism (reviewed by Gollasch and Nelson38). Yang et al39 show that inhibitors of α and β PKC inhibit the ethanol-induced contraction of cerebral arterial smooth muscle as well as the ethanol-induced increase in intracellular Ca++. To determine if α-defensin has any direct interaction with PKC present in the SMCs, we incubated the cells with radiolabeled α-defensin at 37°C for 30 minutes. At the end of incubation the cells were washed and lysed. Anti-α or -β PKC antibodies were added and later precipitated by protein G conjugated to beads, as described by Higazi et al.40Figure 9 shows that radiolabeled α-defensin is immunoprecipitated by anti-PKC antibodies, whereas irrelevant IgG had no effect. These data indicate that α-defensin added to SMCs interacts with intracellular PKC α and β. Figure 9shows that the presence of anti-LRP antibodies during incubation of the cells with radiolabeled α-defensin inhibited the coimmunoprecipitation of α-defensin with PKC. In contrast, anti-LRP antibodies added after cell lysis had no effect on the precipitation of radiolabeled α-defensin (not shown).

Coimmunoprecipitation of α-defensin with PKC.

SMCs were incubated with radiolabeled α-defensin at 37°C for 30 minutes. At the end of incubation the cells were washed and lysed. Antibodies against PKC α (Anti-a), PKC β (Anti-b), or irrelevant antibodies (ir Ab) were added to the lysed cells and later precipitated by protein G conjugated to beads. In another set of experiments, the anti-LRP antibodies were added to the cells before the α-defensin and anti–α PKC antibodies (Anti-LRP-a) or anti–β PKC antibodies (Anti-LRP-b).

Coimmunoprecipitation of α-defensin with PKC.

SMCs were incubated with radiolabeled α-defensin at 37°C for 30 minutes. At the end of incubation the cells were washed and lysed. Antibodies against PKC α (Anti-a), PKC β (Anti-b), or irrelevant antibodies (ir Ab) were added to the lysed cells and later precipitated by protein G conjugated to beads. In another set of experiments, the anti-LRP antibodies were added to the cells before the α-defensin and anti–α PKC antibodies (Anti-LRP-a) or anti–β PKC antibodies (Anti-LRP-b).

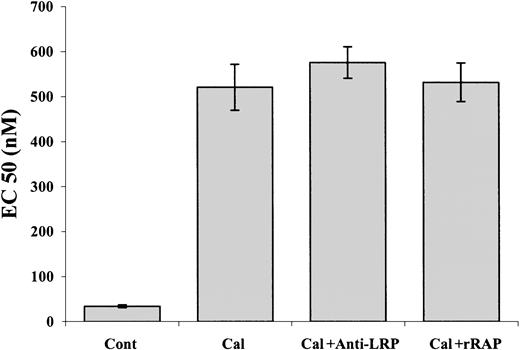

Our data show that α-defensin interacts with intracellular PKC; the data of Charp et al31 indicate that this interaction leads to inhibition of the enzyme. To confirm that inhibition of PKC is sufficient to induce inhibition of PE-induced SMC contraction, we examined the effect of other known inhibitors of PKC. Figure10 shows that calphostin C at a concentration of 1 μM inhibited the PE-induced contraction of denuded aorta. In contrast to its inhibitory effect on the PE-induced vasoconstriction and as in the case of α-defensin, 1 μM calphostin C alone had no effect on SMC contraction (not shown). These results support our conclusions concerning the mechanism of the inhibitory effect of α-defensin. Neither anti-LRP antibodies nor rRAP affected the inhibitory effect of calphostin C (Figure 10).

The effect of calphostin C on PE-induced contraction of aortic rings.

Contraction of rat's aortic rings was induced by PE alone (Cont) or in the presence of 1 μM calphostin C (Cal), calphostin C and anti-LRP antibodies (Cal+ Anti-LRP), or calphostin C and rRAP (Cal+rRAP).

The effect of calphostin C on PE-induced contraction of aortic rings.

Contraction of rat's aortic rings was induced by PE alone (Cont) or in the presence of 1 μM calphostin C (Cal), calphostin C and anti-LRP antibodies (Cal+ Anti-LRP), or calphostin C and rRAP (Cal+rRAP).

Discussion

We have previously reported that α-defensin is found in human arteries11 in and around vascular SMCs.14 The present study shows that α-defensin, at concentrations below those reached during pathological conditions,5 inhibits the contractility of vascular SMCs. The inhibitory effect of α-defensin on the contractility of SMCs is exerted by blocking the increase in intracellular Ca++ induced by PE.

The effect of α-defensin on SMCs is mediated through LRP; this conclusion is based on results of several experiments in which anti-LRP antibodies or rRAP inhibited (1) the α-defensin effect on contraction of aortic rings and on Ca++ mobilization induced by PE in SMCs, (2) binding and internalization of α-defensin by SMCs, and (3) the interaction of α-defensin with intracellular PKC. Furthermore, isolated LRP binds α-defensin in a specific fashion, and anti-LRP antibodies or rRAP inhibit the binding.

The involvement of LRP in the regulation of intracellular Ca++ by α-defensin is consistent with the emerging literature on the signal-transducing properties of this receptor; LRP has been shown to mediate the mitogenic effect α2-macroglobulin41 in SMCs and, more recently, Bacskai et al reported that binding of α2-macroglobulin to LRP increased Ca++ influx into cultured neurons28 by inducing receptor dimerization.

However, in contrast to other known LRP ligands reported to increase intracellular Ca++, binding of α-defensin alone has no direct effect on Ca++ mobilization or on SMC contraction. Rather, binding of α-defensin to LRP modulates the responsiveness of cell to the agonists PE, that bind to other receptors to induce Ca++ mobilization and SMC contraction. The possibility that defensin induces its effect by interfering with PKC activity could explain the observation that it inhibits PE-induced contraction, although it has no intrinsic effects. PKC is inactive in resting cells; therefore, addition of an inhibitor (such as α-defensin or calphostin C) should induce no response.

Apparently it seems difficult to reconcile our findings about the LRP as a mediator of signal transduction with the notion of an endocytic receptor that is delivered to lysosomes—in other words, how defensin, which is probably internalized into endosomes with LRP, gains access to PKC in the cytoplasm. This question has indeed been asked with respect to the HIV-Tat protein that binds to LRP, is internalized into endosomes, and is later translocated by a process that is poorly understood to the nucleus where it stimulates transcription.42 Furthermore, Pseudomonasexotoxin A, which mediates adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribosylation of elongation factor 2 in the cytoplasm, enters the cell exclusively via LRP.43 In the case of exotoxin A, the toxin is composed of a single-chain polypeptide that harbors a fusogenic domain, which mediates the translocation of the toxin into the cytoplasm.43

Another observation that is pertinent to the role of LRP in signal transduction is the increasing number of cytoplasmic proteins that have been found to interact with the receptor. A search for such proteins was initiated because it became impossible to reconcile a bewildering spectrum of experimental observations relating to various functions of LRP and other members of the LDL receptor gene family with a simple role as an endocytic receptor or cellular transporter of extracellular ligands.42

When all data are taken together, it appears likely that the α-defensin regulation of SMC contraction and intracellular Ca++ concentrations is mediated by LRP. Taking into consideration that LRP can interact with several intracellular proteins,44 it could be expected that different ligands may induce different responses. It is feasible that some of the LRP ligands inhibit PKC activity, and it will not come as a surprise if other LRP ligands will stimulate the activity of PKC. There is no doubt that additional studies will have to be performed to clarify the details of the signaling pathway that mediates the effect of α-defensin and LRP on SMC contraction.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 5, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1080.

Supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health HL 67381-01, HL60169, and HL58107.

T.N. and S.A. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Abd Al-Roof Higazi, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 513A Stellar-Chance, 422 Curie Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail:higazi@mail.med.upenn.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal