Abstract

The use of antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides (ODN) is a potential method to switch off gene expression. The poor cellular uptake of ODN in primary cells still is a limiting factor that may contribute to the lack of functional efficacy. Various forms of cationic lipids have been developed for efficient delivery of nucleic acids into different cell types. We examined the two cationic lipids DOTAP and DOSPER to improve uptake of ODN into primary human hematopoietic cells. Using a radiolabeled 23-mer, ODN uptake into blood-derived mononuclear cells could be increased 42- to 93-fold by DOTAP and 440- to 1,025-fold by DOSPER compared with application of ODN alone. DOTAP was also effective for delivery of ODN into leukocytes within whole blood, which may resemble more closely the in vivo conditions. As assessed by fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated ODN both cationic lipids enhanced cytoplasmic accumulation of ODN in endosome/lysosome-like structures with a partial shift of fluorescence to the whole cytoplasm and the nucleus following an incubation of 24 hours. ODN uptake by cationic lipids into different hematopoietic cell subsets was examined by dual-color immunofluorescence analysis with subset-specific monoclonal antibodies. We found a cell type–dependent delivery of ODN with greatest uptake in monocytes and smallest uptake in T cells. CD34+ cells, B cells, and granulocytes took up ODN at an intermediate level. Uptake of ODN into isolated CD34+cells could be increased 100- to 240-fold using cationic lipids compared with application of ODN alone. Stimulation of CD34+ cells by interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-6, and stem cell factor did not significantly improve cationic lipid-mediated ODN delivery. Sequence-specific antisense effects in clonogenic assays could be shown by transfection of bcr-abl oncogene-directed antisense ODN into primary cells of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia using this established protocol. In conclusion, cationic lipids may be useful tools for delivery of antisense ODN into primary hematopoietic cells. These studies provide a basis for clinical protocols in the treatment of hematopoietic cells in patients with hematologic malignancies and viral diseases by antisense ODN.

ANTISENSE oligodeoxyribonucleotides (ODN) are capable of downregulating gene expression and are used for the assessment of gene function and for therapeutic purposes.1-3 Several clinical trials are ongoing with antisense ODN directed to hematopoietic cells for the treatment of hematologic malignancies and viral diseases. For instance, a human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)–directed antisense ODN is used for systemic in vivo administration in patients with aquired immunodeficiency syndrome to protect normal T lymphocytes and macrophages.4 In other clinical trials bcr-abl-, c-myb-, or p53-directed antisense ODN were used for systemic therapy or for ex vivo treatment of hematopoietic cells in patients with acute and chronic myelogenous leukemia or advanced myelodysplastic syndrome.5-8 Functional efficacy of ODN requires not only the selection of an appropriate target sequence9-12 but also a sufficient intracellular concentration. The latter one depends on the degree of cellular uptake, the intracellular distribution, and the rate of degradation of ODN by serum and cytoplasmic nucleases.1 Anionic ODN cannot diffuse through cell membranes, but are actively taken up by endocytosis.13-15As a result, only a small amount of extracellular ODN is available in the cytosol due to the limited capacity of the endocytotic process and the lysosomal degradation. In the light of the ongoing clinical studies, an increased stability and uptake of ODN into hematopoietic cells could improve the efficacy of antisense nucleic acid–based therapies. A variety of cationic lipids with low toxicity are protective against degradation and can facilitate the transport of ODN into different cell types mainly by endocytosis even in the presence of human serum.16-19

In this study, we examined the delivery of phosphorothioate-modified ODN by cationic lipids into primary human hematopoietic cells, including CD34+ cells using the cationic lipids DOTAP and DOSPER under ex vivo culture conditions as well as under conditions resembling the in vivo situation. For quantitative analyses the experiments were performed with 32P-labeled ODN followed by liquid scintillation counting and gel electrophoresis of cellular extracts. In addition, fluorescein-labeled ODN were used to examine subcellular localization and cell subset-dependent uptake. For demonstration of functional effects of cationic lipid-mediated ODN delivery primary cells of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) were treated by bcr-abl–directed ODN and suppression of clonogenic growth was examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (MNC) were obtained from patients with hematologic malignancies or solid tumors in complete remission. Cells were obtained by leukapheresis using a Fenwal CS3000 (Baxter Deutschland, Munich, Germany) after cytotoxic chemotherapy supported with recombinant human G-CSF (R-metHuG-CSF; Amgen, Thousands Oaks, CA). Primary cells from patients with CML were obtained from peripheral blood by vein puncture. Red blood cells and cell debris were removed by density centrifugation using the lymphocyte separation medium Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway) as previously described.20 Separation of CD34+ cells from leukapheresis products was performed using the miniMACS immunomagnetic separation system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions as previously described.20 For transfection experiments cells were cultured in RPMI-1640-medium (CC Pro GmbH, Neustadt/Weinstrasse, Germany) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), 100 IU/mL penicillin (Life Technologies, Eggenstein, Germany), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (Life Technologies). For culture of CD34+ cells, interleukin-3 (IL-3) (20 ng/mL), stem cell factor (SCF) (50 ng/mL), and IL-6 (20 ng/mL) were added to the culture medium in some experiments. Cytokines were obtained from PromoCell (Heidelberg, Germany).

Oligodeoxyribonucleotide synthesis and labeling.

The ODN used for transfection studies were derived from bcr-abloncogene-directed antisense nucleic acids and had the following sequences: antisense-b3a2(A): 5′-GCTGAAGGGCTTTTGAACTCTGC-3′,11scrambled-b3a2(A): 5′-TTATTGAGGGTGATCCGCTAGCC-3′, anti-sense-b3a2(B): 5′-GCTGAAGGGCTTTTGAACTCTGCTTAAA-3′,11scrambled-b3a2(B): 5′-AGAGGTCACGCTTTTAGAGATTGCTTCA-3′, antisense-b2a2: 5′-CGCTGAAGGGCTTCTTCCTTATTGAT-3′,21scrambled- b2a2: 5′-TGGTCATACAGGCCTATTTCGTCTTG-3′. In a data base research using the softwares of the Heidelberg Unix Sequence Analysis Resources (HUSAR, version 4.0; DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany) no homology of the used scrambled ODN with any human sequence of the EMBL data bank was found. The ODN were obtained from Interactiva (Ulm, Germany). They were synthesized using standard phosphoramidate chemistry. The two internucleotide linkages at the 3′ and 5′ end of the ODN were phosphorothioates, and the internal deoxyribonucleotides were connected by phosphodiesters. For fluorescent labeling the last coupling step was performed using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled amidite. The ODN were purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and lyophilized after synthesis by the manufacturer. Before use ODN were resolved in HEPES-buffer (20 mmol/L, pH 7.4). Radioactive labeling of the 5-ends was performed by phosphorylation as described.22 Briefly, 40 pmol of ODN was incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C with 70 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 10 mmol/L MgCl2, 5 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 150 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany) and 30 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Schwalbach/Taunus, Germany) in a final volume of 40 μL. After heating to 68°C for 10 minutes the ODN were purified by gel filtration (Sephadex G-50; Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany). After precipitation with ethanol the ODN were dissolved in TE-buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 1 mmol/L EDTA). Chemicals were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Treatment of cells by ODN and cationic lipids.

Before transfection, ODN were incubated with the respective cationic lipid for 15 minutes at room temperature for formation of ODN/cationic lipid complexes. Using DOTAP (N-[1-(2,3-Dioleoyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium methylsulfate; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), 3 μg ODN (corresponding to a final concentration of a 23-mer ODN in 500 μL cell suspension of 0.84 μmol/L) was mixed with 15 μL cationic lipid (1 μg/μL) and HEPES-buffer (20 mmol/L, pH 7.4) to a final volume of 75 μL. Using DOSPER (1,3-Di-Oleoyloxy-2-(6-Carboxy-spermyl)-propyl-amid; Boehringer Mannheim), 5.4 μg ODN (final concentration: 1.5 μmol/L) was mixed with 14 μL cationic lipid (1 μg/μL) and HBS-buffer (HEPES 20 mmol/L, pH 7.4; NaCl 150 mmol/L) to a final volume of 100 μL. When using an amount of ODN differing from that given above, the amount of cationic lipid was altered correspondingly. For transfection of radioactively labeled ODN, the specific activity of oligonucleotides was 3 × 109 cpm/μmol. After 15 minutes the ODN/cationic lipid mixture was added dropwise to the cell suspension which was incubated at 37°C for at least 30 minutes before transfection. MNC as well as CD34+ cells were incubated in a final volume of 500 μL at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Cells were incubated with the ODN between 30 minutes and 27 hours at 37°C. After incubation, the cells were washed at 4°C once with PBS-buffer (KCl 0.2 g/L; KH2PO4 0.2 g/L; NaCl 8.00 g/L; Na2HPO4 1.15 g/L) and with PBS-buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin, respectively. To remove ODN bound to the cell membrane the acid-salt elution method was used as described.23 Briefly, the cell pellet was suspended in an ice-cold solution containing 0.5 mol/L NaCl and 0.2 mol/L acetic acid (pH 2.5), incubated at 4°C for 10 minutes and centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 minutes. After washing and acid-salt elution, the cells were either treated with proteinase K lysis buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3; 50 mmol/L KCl; 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2; 1.5% Tween-20; 1 μg/mL Proteinase K) for measurement of cell-associated radioactivity or washed with PBS-buffer for flow cytometry.

For assessment of cellular uptake of the FITC-molecule cells were incubated for 2 and 24 hours with 0.3 μmol/L FITC (Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) in the presence or absence of cationic lipids.

For transfection of ODN into cells within whole blood, 500 μL of blood anticoagulated by EDTA was incubated in the presence or absence of cationic lipids. The incubation was performed using a rotator to avoid sedimentation of blood cells. After incubation, 100 μL of samples was mixed with 1.9 mL Becton Dickinson 1 × FACS lysing solution (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) for 5 minutes at room temperature for lysis of erythrocytes. The cells were washed, resuspended in proteinase K lysis buffer, and analyzed by scintillation counting.

Quantification of cell-associated ODN.

To determine cell-associated radioactivity cell pellets were incubated with 40 μL of the proteinase K lysis buffer for 1 hour at 56°C. Twenty microliters was analyzed by counting in a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) with 1 mL of liquid scintillation cocktail (Ready Safe; Beckman Instruments). Cellular ODN uptake was expressed as pmol/106 cells. Lysates were examined by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions (12% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 mol/L urea in 89 mmol/L Tris-borate buffer, pH 8.3) to determine the proportion of degraded ODN as well as of removed 5′ phosphate residues. Gels were dried and exposed to x-ray film. Gels were scanned with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Krefeld, Germany) and band intensities were measured using the IMAGE QUANT software (Molecular Dynamics).

Time-dependent decrease of cell-associated full-length ODN was computer-fitted by nonlinear regression curves with single- and double-exponential decays. Best fit was achieved using a double exponential function. The curves were compatible to an at least two-phase or compartment model which can be described by a function of the form: C(t) = Ae-k1t + Be-k2t. C(t) is the amount of full-length ODN at time t, while A and B indicate the amount of full-length ODN at t = 0 in each phase or compartment. The coefficientsk1 and k2 are the rate constants for the decay of full-length ODN from the respective compartment.24 The half-life of ODN in each compartment was obtained from the equation: t1/2 = ln2 /k.25 The overall half-life of intracellular full-length ODN was calculated from the double-exponential function assuming that C(t1/2) = C(0)/2.

Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry.

After washing 1 × 106 transfected cells were stained with the phycoerytherin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) CD7 (clone 3A1; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), CD13 (clone L138; Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany), CD15 (clone 80H5; Immunotech, Marseille, France), CD19 (clone 467; Becton Dickinson), or CD34 (clone 8612; Becton Dickinson) in 500 μL PBS at 4°C for 30 minutes. Isotype-identical MoAbs served as control (IgG1-PE, Becton Dickinson; IgG2a-PE, Becton Dickinson; IgM-PE, Immunotech). After antibody staining, cells were washed and suspended in PBS-buffer. For determination of the proportion of viable cells, propidium iodide (Sigma) was added at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL before analysis. The cells were analyzed using a Becton Dickinson FACScan with a 2-W argon ion laser. Fluorescence was measured using 530/15 nm (FITC) and 575/36 nm (PE) band pass filter. Data were analyzed using the Becton Dickinson Lysis II software after gating on viable cells.

For fluorescence microscopy, FITC-ODN transfected cells were transferred onto slides by centrifugation (1,000 rpm, 5 minutes) with a Shandon Cytospin3 (Life Sciences International, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). In some experiments cells were fixed using 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes. For staining of nuclei, slides were washed once for 5 minutes with 2 × SSC (20 × stock solution: 3 mol/L NaCl; 0.3 mol/L sodium citrate, pH 7.0), once for 10 minutes with 2 × SSC containing 0.2 μg/mL 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma), and once for 5 minutes with 2 × SSC containing 0.05% Tween 20. After staining, cells were embedded under cover slips in Vecta-Shield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Analysis was performed using a fluorescent microscope (Zeiss Axioskop, Jena, Germany).

Clonogenic assay of primary CML cells transfected by ODN.

Mononuclear cells from peripheral blood from patients with CML were incubated two times with an interval of 16 hours by ODN (final concentrations: 1 μmol/L in first and 0.5 μmol/L in second incubation) using the cationic lipid DOTAP as described above. After transfection the cells were seeded in methylcellulose growth medium (MethoCult H4433; StemCell Technology, Vancouver, Canada) at a density between 5 × 104 and 2 × 105cells/mL.21,26 The colony numbers (colony-forming unit granulocyte/macrophage [CFU-GM], burst-forming unit erythrocyte [BFU-E]) were counted after 2 weeks. The type of bcr-ablfusion point in each sample was determined by polymerase chain reaction following reverse transcription as described.27

RESULTS

The use of radioactively labeled ODN provides a suitable method to study ODN uptake into cells in vitro, as it permits to measure the amount and the proportion of internalized full-length ODN.28 Still, it cannot be distinguished between uptake into living and dead cells or specific uptake into the different cell types of blood-derived MNC. FACS analysis permits the assessment of uptake of FITC-labeled ODN on a single cell level, while the intracellular localization and time-dependent distribution can be examined by fluorescence microscopy.16 29-31 In this study, these methods were used to address quantitative as well as qualitative aspects of ODN uptake into primary human hematopoietic cells.

Improvement of cellular uptake of ODN by DOTAP and DOSPER.

The radioactively labeled phosphorothioate-modified 23-mer scrambled-b3a2(A) ODN was used for quantitative analysis of ODN uptake into blood-derived MNC by means of DOTAP and DOSPER. The following parameters were evaluated: (1) the weight ratio of ODN to cationic lipid,32 (2) the dependency on ODN concentration, and (3) the time course of cationic lipid-mediated ODN uptake.

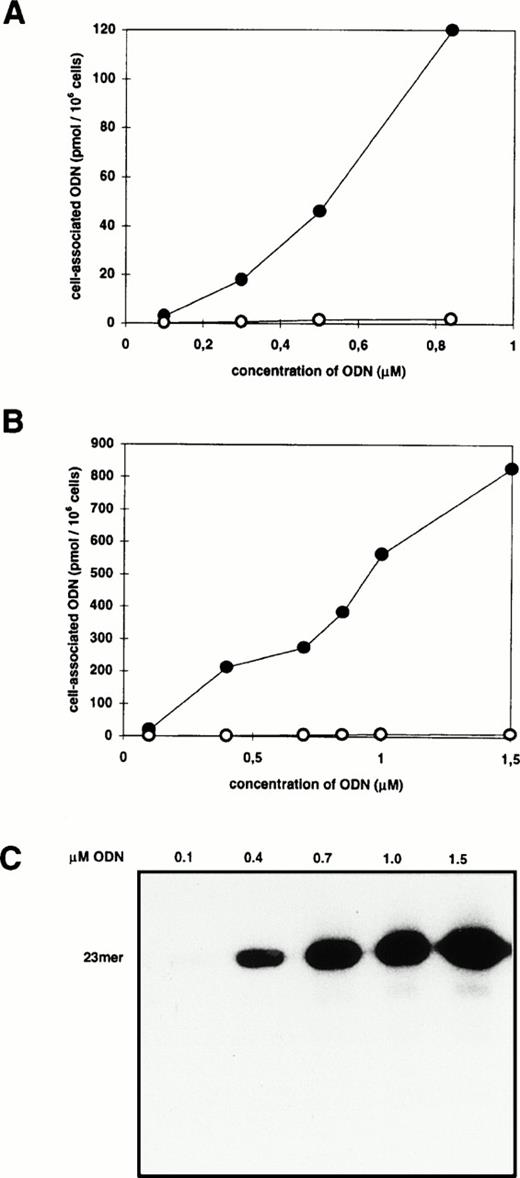

Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L radioactively labeled ODN complexed to different amounts of DOTAP resulting in lipid/ODN ratios (μg/μg) between 1:2 and 10:1. Before analysis, cells were washed according to the acid-salt method to remove extracellularly membrane-bound ODN.23 The cell-associated radioactivity varied between 3 and 30 pmol/106 cells with a maximum when the DOTAP/ODN ratio was between 5:1 and 7:1 (μg:μg) (data not shown). This corresponds to a charge ratio between 2:1 and 3:1 (+/−). Having defined the best DOTAP/ODN ratio, cells were incubated with increasing amounts of ODN/DOTAP complexes up to the toxicity limit of 30 μg DOTAP/mL (Fig1A). The cell-associated radioactivity was dose-dependent without reaching a plateau. The peak value of 120 pmol/106 cells was observed at 0.84 μmol/L ODN which corresponds to 7.2 × 107 ODN molecules per cell. The increase of DOTAP-mediated ODN uptake varied from 42- to 93-fold (mean, 70-fold; standard deviation [SD], 26) in comparison with the application of ODN alone. DNA extracts of transfected cells were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to measure the proportion of full-length ODN (Fig 1C). As shown by x-ray films and PhosphorImager analysis, the proportion of full-length ODN to whole cell–associated radioactivity was more than 80%.

Effect of cationic lipids on cell-associated ODN. Blood-derived mononuclear cells were incubated for 2 hours with increasing amounts of radiolabeled ODN in the absence (○) or presence (•) of DOTAP (A) or DOSPER (B). The amount of cell-associated ODN was measured by liquid scintillation counting of cellular extracts. (C) Analysis of extracts from cells incubated with ODN/DOSPER complexes by denaturing 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Full-length 23-mer ODN are indicated.

Effect of cationic lipids on cell-associated ODN. Blood-derived mononuclear cells were incubated for 2 hours with increasing amounts of radiolabeled ODN in the absence (○) or presence (•) of DOTAP (A) or DOSPER (B). The amount of cell-associated ODN was measured by liquid scintillation counting of cellular extracts. (C) Analysis of extracts from cells incubated with ODN/DOSPER complexes by denaturing 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Full-length 23-mer ODN are indicated.

For the assessment of the time course of ODN uptake, cells were incubated between 30 minutes and 27 hours with 0.3 μmol/L ODN complexed to DOTAP (Fig 2). Approximatly two thirds of the maximum cell-associated radioactivity was observed within the first 2 hours of incubation. During the following 22 hours intracellular ODN accumulated at a significantly lower rate, suggesting that an incubation time between 2 and 8 hours is sufficient for delivery of ODN by DOTAP into blood-derived MNC.

Time course of cationic lipid-mediated ODN uptake in blood-derived mononuclear cells. Cells were incubated with 0.3 μmol/L radiolabeled ODN complexed to DOTAP (○) or DOSPER (•) for the indicated times. Means and standard deviations of three independent experiments are presented.

Time course of cationic lipid-mediated ODN uptake in blood-derived mononuclear cells. Cells were incubated with 0.3 μmol/L radiolabeled ODN complexed to DOTAP (○) or DOSPER (•) for the indicated times. Means and standard deviations of three independent experiments are presented.

Using DOSPER the uptake of ODN in MNC could also be improved significantly, but some parameters were different from the results obtained with DOTAP. The maximum of cell-associated radioactivity was found at a DOSPER/ODN ratio of 2.6:1 (μg:μg) which corresponds to a charge ratio of 3:1 (+/−). There were 800 pmol ODN associated with 106 cells (4.8 × 108 molecules/cell) when the ODN concentration was 1.5 μmol/L (Fig 1B), and the DOSPER-mediated increase of uptake varied between 440- and 1,025-fold (mean, 690-fold; SD, 220) compared with the application of ODN alone. The time course of ODN uptake by DOSPER was also different in comparison with DOTAP, as the cell-associated radioactivity reached a maximum after 2 hours of incubation (Fig 2) followed by a decrease as a function of time. In addition, uptake of the radioactively labeled 26-mer scrambled-b2a2 as well as the 28-mer scrambled-b3a2(B) ODN with different base compositions was measured to look for a sequence dependency of ODN delivery. No differences in cationic lipid-mediated uptake were observed between the 23-mer, the 26-mer, and the 28-mer ODN (data not shown).

Subcellular localization of ODN after transfection with cationic lipids.

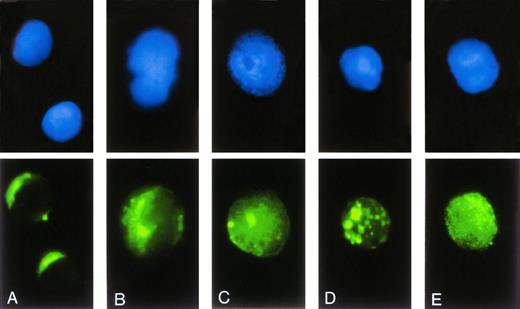

The functional activity of antisense ODN depends on their access to the cellular compartment of the biological target. Therefore, the subcellular localization and intracellular trafficking of ODN was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy using FITC-labeled 23-mer scrambled-b3a2(A) ODN (Fig 3). Incubation of blood-derived MNC with ODN/DOTAP complexes resulted in a faint cytoplasmic stain of lymphoid cells at a circumscript perinuclear area on one side of the cell (Fig 3A). In contrast, approximately 90% of cells with monocyte appearance showed a bright fluorescent staining with a spotted distribution within the cytosol (Fig 3B). Although there was no nuclear fluorescence found after 2 hours of incubation, a homogenous nuclear stain with a pronounced accumulation in the nucleoli was observed after 24 hours (Fig 3C). In approximately 80% of cells the cytoplasmic stain persisted in spotted endosome/lysosome-like structures after 24 hours (Fig 3D), whereas the other cells developed a homogenous cytoplasmic fluorescence (Fig 3E). Similar intracellular distributions of ODN were obtained with DOSPER except for the difference that the proportion of cells with a homogenous cytoplasmic fluorescence after 24 hours reached 50% (data not shown). There was no difference between fixed and unfixed cells, indicating that fixation does not influence subcellular localization of ODN.

Subcellular localization of FITC-labeled ODN. After transfection of 0.3 μmol/L FITC-labeled ODN using DOTAP, cells were transferred on slides by centrifugation, stained by DAPI, and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. The upper row shows the DAPI stained nuclei, the lower row the intracellular distribution of FITC-labeled ODN. (A and B) Representative cells after incubation with ODN/DOTAP complexes for 2 hours. (C through E) Representative cells after an incubation time of 24 hours.

Subcellular localization of FITC-labeled ODN. After transfection of 0.3 μmol/L FITC-labeled ODN using DOTAP, cells were transferred on slides by centrifugation, stained by DAPI, and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. The upper row shows the DAPI stained nuclei, the lower row the intracellular distribution of FITC-labeled ODN. (A and B) Representative cells after incubation with ODN/DOTAP complexes for 2 hours. (C through E) Representative cells after an incubation time of 24 hours.

Transfection of ODN by cationic lipids using whole peripheral blood.

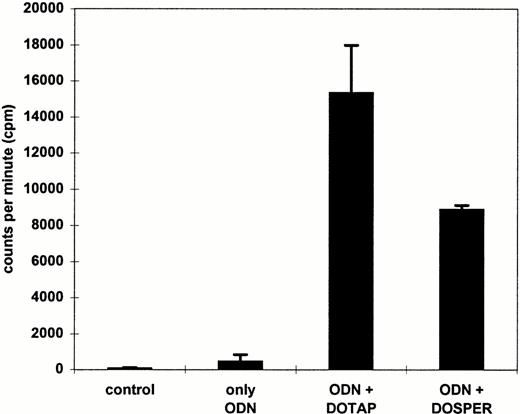

The data presented are helpful for the design of ex vivo transfection protocols of ODN into MNC. On the other hand, antisense ODN can also be used for systemic intravenous administration. Therefore, we measured uptake of radioactively labeled ODN in cells of whole blood which may resemble more closely the in vivo conditions. The peripheral blood was anticoagulated by EDTA, because heparin is a negatively charged macromolecule that may interfere with cationic lipids.33 34In comparison with the use of ODN alone, the uptake into leukocytes was approximately 30-fold and 20-fold greater using DOTAP and DOSPER, respectively (Fig 4). Polyacrylamide gel analyses of DNA extracted from transfected cells were performed to exclude that the radioactive label was displaced from the ODN by serum phosphatases and nucleases. PhosphorImager analyses of gels showed that the proportion of full-length ODN to whole cell–associated radioactivity was more than 80% in each sample (data not shown). As shown by FACS analysis with FITC-labeled ODN complexed to cationic lipids, the fluorescence staining was only found in leukocytes, whereas the erythrocytes were negative (data not shown).

Effect of DOTAP and DOSPER on ODN uptake into leukocytes using whole blood. Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L radiolabeled ODN complexed to cationic lipids. After lysis of erythrocytes, radioactivity associated with white blood cells was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The results from two experiments are indicated.

Effect of DOTAP and DOSPER on ODN uptake into leukocytes using whole blood. Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L radiolabeled ODN complexed to cationic lipids. After lysis of erythrocytes, radioactivity associated with white blood cells was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The results from two experiments are indicated.

Cell subset-dependent ODN uptake.

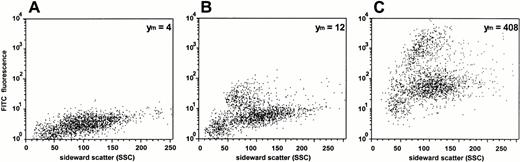

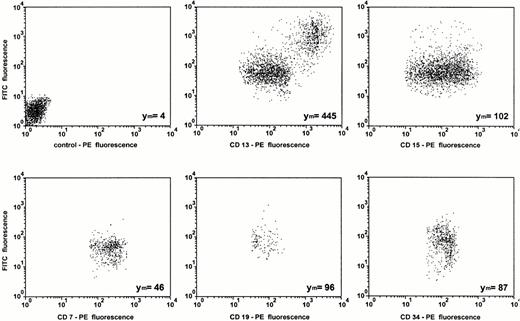

Data obtained from uptake studies using radioactively labeled ODN provide mean values of cell-associated ODN of all cell subsets in the MNC fraction. Therefore, DOTAP-mediated uptake of FITC-labeled ODN was examined by dual-color immunofluorescence analysis with subset specific PE-conjugated MoAbs. The results of one representative experiment of three experiments are shown in Figs 5 and6. As assessed by propidium iodide staining, the proportion of dead cells was less than 5%, reflecting the low toxicity of the transfection. The mean FITC-fluorescence of all cells was approximately 35-fold greater compared with ODN treatment alone (Fig 5). As assessed by sideward scatter gating, greatest uptake of ODN into monocytes could be seen in both samples, with and without DOTAP. This was confirmed by the antibody staining of lineage-specific antigens (Fig 6). Monocytes, as assessed by gating on CD13+and CD15− cells, had the greatest cell-associated fluorescence intensity. The smallest uptake was observed in CD7+ T cells, while the uptake was intermediate in CD15+ myeloid cells, in CD19+ B cells, as well as in CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells.

Analysis of ODN uptake into blood-derived mononuclear cells by flow cytometry. Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L FITC-labeled ODN in the absence (B) or presence (C) of DOTAP. (A) Background fluorescence of cells without ODN incubation. The relative mean fluorescence intensities (Ym) are indicated.

Analysis of ODN uptake into blood-derived mononuclear cells by flow cytometry. Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L FITC-labeled ODN in the absence (B) or presence (C) of DOTAP. (A) Background fluorescence of cells without ODN incubation. The relative mean fluorescence intensities (Ym) are indicated.

Subset dependent ODN uptake into primary blood-derived mononuclear cells. Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L FITC-labeled ODN complexed to DOTAP and stained with the indicated PE-conjugated lineage-specific antibodies before FACS-analysis. Cells were analyzed after gating on the lineage-specific antibody staining. The background fluorescence with an isotype-specific control antibody is shown in the first dot blot. The relative mean FITC fluorescence intensities (Ym) are indicated.

Subset dependent ODN uptake into primary blood-derived mononuclear cells. Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L FITC-labeled ODN complexed to DOTAP and stained with the indicated PE-conjugated lineage-specific antibodies before FACS-analysis. Cells were analyzed after gating on the lineage-specific antibody staining. The background fluorescence with an isotype-specific control antibody is shown in the first dot blot. The relative mean FITC fluorescence intensities (Ym) are indicated.

After a 24-hour incubation of cells with ODN/DOTAP complexes, the mean FITC-fluorescence further increased approximately 4-fold in CD13+ and CD15+ cells and approximately 2.5-fold in CD34+ cells. In contrast, uptake of ODN into CD7+ and CD19+ lymphocytes was not enhanced following the longer incubation time (data not shown). Small and large cells were gated within each subpopulation to exclude that the different efficiency of uptake among the subsets was related to cell volume. The proportion of cell subsets was 78% for CD13+cells, 52% for CD15+ cells, 24% for CD19+cells, 20% for CD7+ cells, and 1.5% for CD34+cells. We found no correlation between the proportion of each cell subset and ODN uptake. The same subset-specific ODN uptake was seen using mononuclear cells from patients with CML in chronic phase as well as using DOSPER instead of DOTAP (data not shown). Incubation of cells with FITC in the presence or absence of cationic lipids showed no increased cellular fluorescence after 2 hours as well as after 24 hours in comparison with untreated cells.

ODN uptake in CD34+ cells.

For application of antisense ODN in ex vivo treatment protocols uptake into enriched CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells is of special interest. Therefore, delivery of ODN by cationic lipids into isolated blood-derived CD34+ cells was examined using radioactively labeled ODN. After an incubation of CD34+cells with the ODN/cationic lipid complexes for 2 hours, the cell-associated radioactivity was increased 100-fold (SD, 6) using DOTAP and 240-fold (SD, 32) using DOSPER compared with application of ODN alone, respectively (data not shown). Isolated CD34+cells were also cultured in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF for 48 hours before transfection to examine whether ODN uptake is greater after cellular activation. The cytokines were chosen, as they stimulate proliferation of CD34+ cells without loss of long-term culture potential.35 Still, stimulation with growth factors did not significantly improve the cationic lipid-mediated ODN uptake in comparison with unstimulated CD34+ cells (Fig 7). As assessed by trypan blue staining and a colony-forming assay in semisolid culture medium, DOTAP and DOSPER had no toxic effects on CD34+ cells after an incubation time of 10 hours with the cationic lipid/ODN complexes (data not shown).

Influence of cellular activation of CD34+cells on cationic lipid-mediated ODN uptake. Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L radiolabeled ODN complexed to DOTAP (□) or DOSPER (▪) with or without a 48-hour preculture in IL-3, IL-6, and SCF supplemented medium. The amount of cell-associated ODN was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The results of two experiments are indicated.

Influence of cellular activation of CD34+cells on cationic lipid-mediated ODN uptake. Cells were incubated for 2 hours with 0.3 μmol/L radiolabeled ODN complexed to DOTAP (□) or DOSPER (▪) with or without a 48-hour preculture in IL-3, IL-6, and SCF supplemented medium. The amount of cell-associated ODN was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The results of two experiments are indicated.

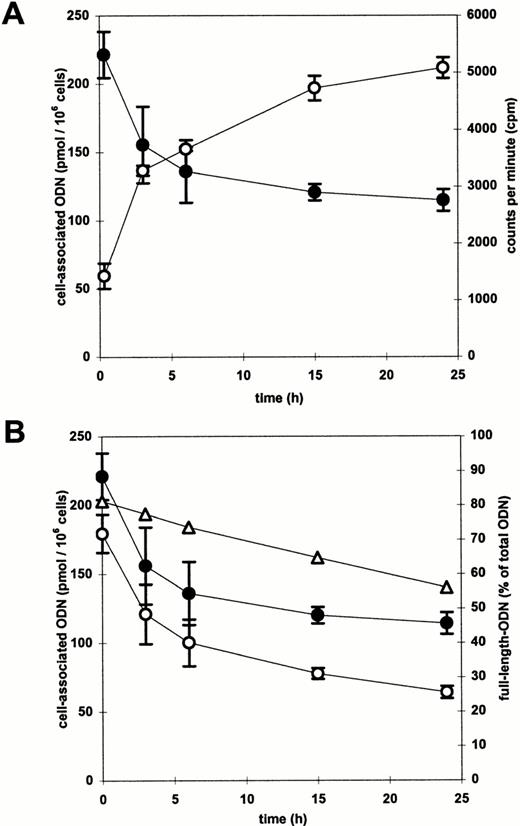

Kinetic analyses of cell- and medium-associated radioactivity were performed to determine the intracellular half-life of ODN in CD34+ cells and the efflux rate of cell-associated radioactivity. Radioactively labeled ODN/DOSPER complexes were added to CD34+ cells for 2 hours, the medium was removed and the cells were incubated with fresh medium devoid of ODN. The time courses of cell-associated as well as medium-associated radioactivity were measured. The cell-associated radioactivity decreased, while the extracellular radioactivity increased as a function of time (Fig 8A). As shown by PhosphorImager analysis of polyacrylamide gels of cellular DNA extracts, the cell-associated ODN degraded during incubation. The proportion of full-length ODN to whole cell-associated radioactivity decreased from 80% to 55% after 24 hours (Fig 8B). Degradation products were more than 95% mononucleotides or phosphate residues without successively shortened ODN (data not shown). These results indicate a very fast degradation after removal of the 5′ or 3′ cap-phosphorothioates. Multiplication of the functions of cell-associated radioactivity and of proportion of full-length ODN resulted in a curve reflecting the kinetics of full-length ODN (Fig8B), which is a relevant parameter with regard to the efficacy of antisense ODN. The kinetics best fit to a bi-exponential function in which the exponential terms represent at least two compartments or phases.24 25 The ODN half-lives of the individual phases or compartments were calculated from the computer fit. The first phase was rapid with a half-life of approximately 2 hours, whereas the second phase was slow, reflected by a half-life of approximately 30 hours. This resulted in an overall half-life of full-length ODN in CD34+ cells of about 10 hours.

(A) Time course of extracellular (○) and cell-associated (•) radioacivity in CD34+ cells. After a 2-hour incubation with radiolabeled ODN/DOSPER complexes the medium was removed and cells were resuspended in fresh medium. Radioactivity was measured at indicated time points by liquid scintillation counting. (B) Time course of cell-associated full-length ODN (○). The proportion of full-length ODN to the whole cell-associated radioactivity as determined by PhosphorImager analysis of a polyacrylamide gel is shown as a function of time by (▵). Multiplication of this function with the function of cell-associated radioactivity (•) resulted in the curve indicating the time course of cell-associated full-length ODN.

(A) Time course of extracellular (○) and cell-associated (•) radioacivity in CD34+ cells. After a 2-hour incubation with radiolabeled ODN/DOSPER complexes the medium was removed and cells were resuspended in fresh medium. Radioactivity was measured at indicated time points by liquid scintillation counting. (B) Time course of cell-associated full-length ODN (○). The proportion of full-length ODN to the whole cell-associated radioactivity as determined by PhosphorImager analysis of a polyacrylamide gel is shown as a function of time by (▵). Multiplication of this function with the function of cell-associated radioactivity (•) resulted in the curve indicating the time course of cell-associated full-length ODN.

Using DOTAP a similar bi-exponential curve with the same overall half-life of full-length ODN was found (data not shown).

Functional effects of DOTAP-mediated ODN delivery.

ODN used in the experiments presented were derived from antisense sequences directed against the CML-related bcr-abloncogene. The CML can serve as a model for antisense ODN-mediated inhibition of leukemic cell growth, because the bcr-ablrearrangement of the Philadelphia-chromosome (Ph+) that results from a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 leads to the expression of a pathological p210 bcr-abl fusion protein in more than 90% of patients. Depending on whether the second exon of the abl gene fuses with bcr exon 2 or 3, two different types of bcr-abl mRNA (b2a2 and b3a2) are found in most cases of CML.36

The functional effects of ODN transfected by DOTAP was examined using primary hematopoietic cells from 9 patients with CML. Seven patients were in chronic phase without previous treatment, 1 patient was in accelerated phase, and 1 in blast crisis. Mononuclear cells were obtained from peripheral blood and the type of bcr-abl fusion point was determined by polymerase chain reaction following reverse transcription of cellular RNA. The b3a2 fusion point-directed antisense-b3a2(B) ODN and the b2a2-directed antisense-b2a2 ODN as well as the respective control ODN with the same nucleotide compositions in scrambled sequence (scrambled-b3a2(B), scrambled-b2a2) were used to assess the antiproliferative activity on the patients' cells in clonogenic assays. ODN were transfected two times with an interval of 16 hours at concentrations of 1 μmol/L and 0.5 μmol/L, respectively. The b3a2 antisense sequence was chosen based on kinetic in vitro selection to achieve specific hybridization with the b3a2bcr-abl fusion sequences while sparing the wild-type sequences bcr or abl.11 In 3 of 9 cases, fusion point-specific inhibition of colony formation was observed ranging between 39% and 72% at a low variation within the experiments performed in duplicates (Table 1). In none of the 9 cases, any inhibitory effects were observed with scrambled control sequences or alternative junctional antisense ODN; ie, inhibition was only measured with bcr-abl junction-specific antisense ODN in cells with the appropriate target mRNA. Colony formation of bcr-abl− cells was not influenced after transfection of ODN by DOTAP. The transfection procedure alone had also no effect on cell proliferation.

DISCUSSION

In this report we show that ODN uptake into human blood-derived MNC can be greatly improved by cationic lipids. Because primary hematopoietic cells are target cells for the treatment of patients with hematologic diseases and viral infections by antisense ODN,4-8 an efficient delivery of nucleic acids is required to obtain functional effects. We found an increase of ODN uptake by the cationic lipids DOTAP and DOSPER between 30- and 800-fold in comparison to the values achieved with ODN alone. This enhancement is significantly greater than that observed for other cell types. For instance, Capaccioli et al17 showed a 25-fold increase of ODN uptake into a lymphoblastic cell line when DOTAP was added. Other groups described a 2-to 10-fold greater ODN uptake by cationic lipids into primary endothelial cells as well as leukemic and cervical cancer cell lines16,28,37 when compared with an incubation of ODN alone. On the other hand, there was no effect of cationic lipids on the uptake and inhibitory activity of antisense ODN in primary keratinocytes.29 Using FITC-labeled ODN, we found that ODN delivery was dependent on the cell type with smallest uptake into T cells. Uptake into monocytes was 30-fold, into CD34+ cells, B cells, and granulocytes about 2-fold greater compared with T cells, while there was no measurable uptake into erythrocytes. Still, an exact quantification of FITC-labeled ODN uptake is difficult because the emission intensity of FITC is pH dependent.24 38 Therefore, in a cellular compartment with low pH, such as lysosomes, the amount of intracellular FITC-labeled ODN might be underestimated by FACS analysis.

The great variability of uptake obtained with different cell types and lipids may be related to two essential steps of ODN uptake into cells: (1) The interaction of the positively charged cationic lipid/DNA complex with anionic residues on the cell surface39 and (2) the endocytosis of the complex by the cells.18,40 There is some evidence that membrane-associated sulfated proteoglycans are involved in the transfection by cationic lipids.41Proteoglycans consist of a core protein covalently linked to one or more sulfated glycosaminoglycans.42 Hematopoietic cells have a different expression pattern of the hematopoietic proteoglycan core protein (HpPG) dependent on the lineage and state of differentiation.43 Monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils express the HpPG at higher levels than lymphocytes, neutrophils, and immature myeloid cells. Therefore, a variable expression of proteoglycans on different cell types may influence the susceptibility of cells to transfection. Assuming that ODN/cationic lipid complexes are taken up by endocytosis,18,40 the differences observed between the cell subsets could also be explained by a greater endocytosis activity of monocytes compared with T or B lymphocytes.44 A similar cell subset–dependent ODN delivery without the use of transfection reagents was described for human and murine hematopoietic cells.31,45 In contrast to the data of Zhao et al,31 who used ODN alone, we could not observe an increased cellular uptake of ODN/cationic lipid complexes into CD34+ cells following incubation with a cocktail of the cytokines IL-3, IL-6, and SCF. This could indicate that uptake of cationic lipid/ODN complexes in contrast to ODN alone is independent from cellular activation of CD34+ cells. The subset dependent uptake is important with respect to clinical application of antisense ODN. DOTAP and DOSPER may be less efficient in delivery of ODN into HIV-1–infected T cells compared with macrophages and monocytes. Additionally, our data suggest a significant benefit of cationic lipids for uptake into silent and activated CD34+cells which is of relevance for ex vivo purging protocols of hematopoietic stem cells.

The difference of the transfection efficacy between DOTAP and DOSPER may be related to the tetravalent cationic structure of the DOSPER molecule, while DOTAP is a monocationic liposomal reagent. The polycationic lipid may lead to a better formation of the lipid/ODN complex and improved interaction between the complex and the negatively charged cell surface. The initial peak after 2 hours with subsequent decrease of cell-associated radioactivity using DOSPER in comparison with continuous increase of ODN uptake using DOTAP may be related to a lower stability of the DOSPER molecule compared with DOTAP. Therefore, an efficient uptake can be observed during the first 2 hours of the transfection procedure, but afterwards metabolization and excretion of cell-associated radioactivity may overcome the uptake of extracellular ODN as a result of destabilization of ODN/DOSPER complexes. This hypothesis is supported by the reduced efficacy of ODN uptake by DOSPER compared with DOTAP using whole blood conditions instead of the isolated mononuclear cell fraction. Differences in transfection efficacies depending on the chemical structure of the cationic lipids have been also described for other liposomes.46

Nucleic acid/cationic lipid complexes are mainly internalized via endocytosis.18,40 The mechanism of release of the nucleic acid from the endosome to the cytoplasm as well as the intracellular trafficking are poorly understood. Recently, a model for intracellular release of DNA from cationic liposomes into the cytoplasm was proposed.33,34 After internalization via endocytosis the DNA/cationic lipid complex destabilizes the endosomal membrane as a result of a flip-flop exchange between anionic and cationic lipids. Thereby, the DNA is displaced from the complex allowing the ODN to diffuse into the cytoplasm. Alternatively, full-length ODN could also be released immediately from endosomes to the extracellular compartment by exocytosis24,25,47 or the DNA/cationic lipid complex is transferred to lysosomes, where the nucleic acid is rapidly degraded by nucleases. Our results on the intracellular localization of ODN as well as the kinetic data are consistent with these views. Accumulation of ODN in cytoplasmic granules which presumably represent endosomes and lysosomes was observed after 2 hours of incubation with FITC-labeled ODN. The nuclear localization of fluorescence after 24 hours indicated a significant release of ODN from endocytic vesicles into the cytosol and subsequent transport to the nucleus, suggesting that ODN may reach the target RNA. Additionally, the kinetic data on the efflux of cell-associated radioactivity from ODN-transfected CD34+cells can be described in a mathematical model for ODN trafficking with at least two phases or compartments.1 24 The first phase or compartment with a short half-life of 2 hours may reflect the rapid transfer of ODN from endosomes to the cell surface or to lysosomes with subsequent degradation and exocytosis. The second and further phases with slow turnover may reflect the release of ODN from endosomes to other cellular compartments followed by metabolization. The overall decrease of cell-associated ODN in CD34+ cells resulted in a half-life of full-length ODN of 10 hours. These kinetic data indicate that for targeting a gene which codes for a RNA and a protein with long half-lives a single transfection of antisense ODN may not be sufficient and further transfections after intervals of 10 hours using the half ODN dose may be useful.

The results obtained in ex vivo experiments may differ from ODN uptake in vivo. Although DOTAP and DOSPER are effective in the presence of human serum,17 transfection can be hampered by charged components of the blood such as heparin.34 Therefore, the efficacy of ODN delivery was evaluated under conditions mimicking an in vivo administration. Using DOSPER the enhancement of ODN uptake was significantly decreased from 800-fold to about 20-fold when whole blood was used instead of defined ex vivo conditions. The efficacy of DOTAP was less influenced by components of peripheral blood and still an 30-fold increase of ODN was observed. This indicates that DOTAP may be suitable for systemic in vivo application.

Still, one has to take into account that the FITC label or the sequence of the ODN may influence uptake and intracellular trafficking of the nucleic acid.48 However, we did not find differences in the extent of uptake using a 26-mer and a 28-mer ODN with various sequences, suggesting that the data obtained with the 23-mer ODN may be representative for other ODN. Nevertheless, it is important to ensure for each individual ODN an efficient cationic lipid-mediated delivery into the respective cell type before using the ODN in cell culture experiments or clinical trials.

A great uptake of ODN does not necessarily translate into biological activity, because antisense ODN may lack an efficient binding with the target RNA or they could remain in endosomes and lysosomes without reaching their target. Because the uptake studies were performed with ODN derived from bcr-abl oncogene-directed antisense sequences, primary cells from patients with CML were used to look for functional effects of ODN delivered by cationic lipids. Reports on the inhibitory effects of bcr-abl–directed antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides on the proliferation of Ph+primary leukemic cells are heterogeneous and even contradictory with respect to sequence specificity and efficacy in some instances.21,49-54 This heterogeneity may be related to differences in cell-culture conditions, to the target sequence, as well as to the high ODN concentrations ranging between 5 μmol/L and 20 μmol/L, which could result in unspecific effects. We found in one third of the cases a fusion point-specific inhibition of clonogenic growth by ex vivo treatment of primary CML cells with bcr-ablantisense ODN/DOTAP complexes using an ODN concentration of only 1 μmol/L, which indicates a benefit of DOTAP for functional effects of ODN. The lack of growth inhibition observed with alternative junctional and scrambled control ODN implies that the antiproliferative activity is due to a specific antisense effect. A correlation between inhibition of colony formation in these cases and any patients' characteristics such as disease status or type of fusion point was not found. Thus, the antisense ODN may only be beneficial for a subset of patients with Ph+ CML. The lack of efficacy in the other patients remains unclear. There might be additional genomic alterations or alternative signal transduction pathways that make the cells independent frombcr-abl expression.55 56

In conclusion, DOTAP and DOSPER have a significant advantage over the use of ODN alone for delivery of ODN into primary hematopoietic cells. Thus, using cationic lipids in clinical studies the ODN can be applied at a lower dose to reduce side effects and cytotoxicity. The data obtained in this study, including those obtained with the primary cells of patients with CML, can serve as basis for ongoing and future clinical ex vivo purging protocols of hematopoietic stem cells in the treatment of hematologic diseases such as CML as well as for systemic in vivo administration of antisense ODN in leukemias and viral infections.

Address reprint requests to Rainer Haas, MD, Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik V, Universität Heidelberg, Hospitalstr. 3, 69115 Heidelberg, Germany.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.