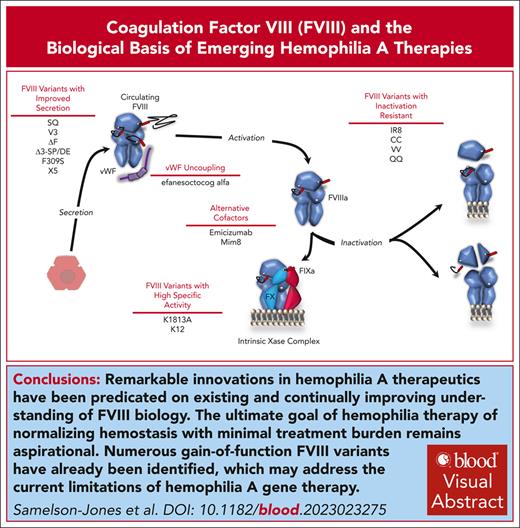

Visual Abstract

Coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) is essential for hemostasis. After activation, it combines with activated FIX (FIXa) on anionic membranes to form the intrinsic Xase enzyme complex, responsible for activating FX in the rate-limiting step of sustained coagulation. Hemophilia A (HA) and hemophilia B are due to inherited deficiencies in the activity of FVIII and FIX, respectively. Treatment of HA over the last decade has benefited from an improved understanding of FVIII biology, including its secretion pathway, its interaction with von Willebrand factor in circulation, the biochemical nature of its FIXa cofactor activity, the regulation of activated FVIII by inactivation pathways, and its surprising immunogenicity. This has facilitated biotechnology innovations with first-in-class examples of several new therapeutic modalities recently receiving regulatory approval for HA, including FVIII-mimetic bispecific antibodies and recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vector–based gene therapy. Biological insights into FVIII also guide the development and use of gain-of-function FVIII variants aimed at addressing the limitations of first-generation rAAV vectors for HA. Several gain-of-function FVIII variants designed to have improved secretion are currently incorporated in second-generation rAAV vectors and have recently entered clinical trials. Continued mutually reinforcing advancements in the understanding of FVIII biology and treatments for HA are necessary to achieve the ultimate goal of hemophilia therapy: normalizing hemostasis and optimizing well-being with minimal treatment burden for all patients worldwide.

Introduction

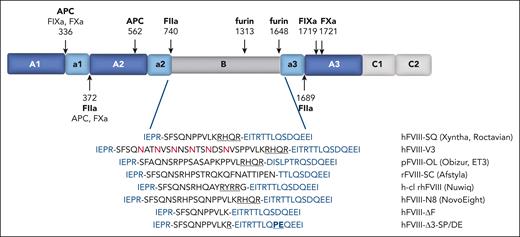

Coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) is critical for hemostasis. It is a large 280 kDa glycoprotein with a domain structure of A1-a1-A2-a2-B-a3-A3-C1-C2 (Figure 1). Activated FVIII (FVIIIa) is an essential cofactor for the proteolytic activation of FX by FIXa. FXa generation by the intrinsic Xase enzyme complex (composed of FVIIIa and FIXa on anionic membranes; Figure 2) is the rate-limiting step in sustained coagulation. Deficiencies in the intrinsic Xase function result in hemophilia. Hemophilia A (HA) and hemophilia B are due to inherited deficiencies in FVIII and FIX, respectively. The severity of bleeding in hemophilia is correlated with the residual factor level; hemophilia is currently categorized as severe, moderate, or mild based on factor levels of <1%, 1% to 5%, or 5% to 40% normal, respectively.

Domain structure of FVIII and BDD linker sequences. The A1-a1-A2-a2-B-a3-A3-C1-C2 domain structure of FVIII is illustrated. The sites of proteolysis are indicated by arrows with the relevant proteases specified. The sequences of the linkers that replace the B domain in BDD-FVIII variants are listed at the bottom (black), as well as the flanking sequences from the a2 and a3 domains (blue). The retained furin recognition motif from 1645 to 1648 is underlined, and the inserted N-glycosylation sites in FVIII-V3 are in red. The sites of S1657P and D1658E substitutions in a3 for hFVIII-Δ3-SP/DE are also highlighted.

Domain structure of FVIII and BDD linker sequences. The A1-a1-A2-a2-B-a3-A3-C1-C2 domain structure of FVIII is illustrated. The sites of proteolysis are indicated by arrows with the relevant proteases specified. The sequences of the linkers that replace the B domain in BDD-FVIII variants are listed at the bottom (black), as well as the flanking sequences from the a2 and a3 domains (blue). The retained furin recognition motif from 1645 to 1648 is underlined, and the inserted N-glycosylation sites in FVIII-V3 are in red. The sites of S1657P and D1658E substitutions in a3 for hFVIII-Δ3-SP/DE are also highlighted.

The therapeutic development of HA has been driven by insights into the biology of FVIII. Over the last decade, 3 new therapeutic modalities have emerged: (1) extended half-life (EHL) FVIII molecules, (2) nonfactor therapies, including bispecific antibodies that bind FIXa and FX to recapitulate aspects of FVIIIa cofactor function (FVIII mimetics), and (3) gene therapy.1-4 In turn, these new drugs have clarified FVIII biology but also revealed new scientific questions. However, a major limitation of FVIII-containing treatments is the development of neutralizing anti-FVIII antibodies (inhibitors), which occur in ∼30% of severe HA. Immunogenicity is thus a prominent safety concern of any new HA therapeutic.5

Here, we review the evolving understanding of FVIII biology, including the molecular basis of its secretion, cofactor activity, regulation, and its surprising immunogenicity. We discuss how these biological insights continue to facilitate the development of HA therapies. We specifically focused on the development of gain-of-function FVIII variants as a potential solution to the emerging limitations of recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) gene therapy. As reviewed elsewhere,3,4 current rAAV vectors for HA are limited by either (1) initially high FVIII levels that decline after year-1, or (2) FVIII levels in the low-mild range (5%-20% normal) that are stable for ≥3 years. One way to cut this Gordian knot would be to use a gain-of-function FVIII variant that would allow for durable, low FVIII antigen levels but high hemostatic function. This would be analogous to the use of a gain-of-function FIX variant Padua in all current rAAV gene therapies for hemophilia B.6

Synthesis, posttranslational modifications, and secretion

FVIII is synthesized as a 2351-residue single-chain polypeptide, with the first 19 amino acids comprising the secretory signal peptide. Herein, we used the legacy amino acid numbering system with position-1 as the N-terminal alanine of circulating FVIII. FVIII is endogenously expressed from endothelial cells, predominantly liver sinusoidal endothelial cells.7,8 After translocation to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), FVIII interacts with the protein chaperones calnexin/calreticulin system and BiP.9 BiP is a key component of the unfolded protein response (UPR), a conserved cellular pathway that balances protein synthesis with the protein-folding capacity of the ER.10 The UPR is activated by ER stress and a sustained UPR can lead to cell death.

High FVIII expression from mammalian cells initiates the UPR including increasing BiP expression and apoptosis.11-15 FVIII is also poorly secreted from mammalian cells: its secretion efficiency is at least fivefold lower than the similarly sized and homologous FV.16 One answer to why FVIII triggers the UPR and is poorly secreted is the recent observation that FVIII aggregates within the ER into amyloid-like fibrils, which is limited by the calnexin/calreticulin system and BiP.17 A 79-amino acid region in the A1 domain (251-331) was implicated as critical for aggregation.17 Within this region is a hydrophobic motif (291-310) that is absent in FV, potentially explaining some of the differences in FVIII and FV secretion efficiency. These results are also consistent with those of previous studies implicating the C-terminus of A1 as impeding FVIII (but not FV) secretion.18

Although the role of the UPR in endogenous FVIII secretion is unclear, the induction of UPR by FVIII after gene transfer is an emerging safety and efficacy limitation, including an evolving hypothesis that UPR induction may prevent durable FVIII expression at normal levels.3,4,11-15 Transient FVIII expression after hepatocyte gene transfer in mice resulted in a significant increase in hepatocellular carcinoma after 1 year of a high-fat diet compared with controls that did not express FVIII.19 This suggests that even transient ectopic FVIII expression may be sufficient in certain scenarios to generate enough ER stress to have pathological consequences. Notably, the rate of cancer development was significantly lower in FVIII variants with improved secretion and decreased aggregation, further linking FVIII aggregation with secretion inefficiency.

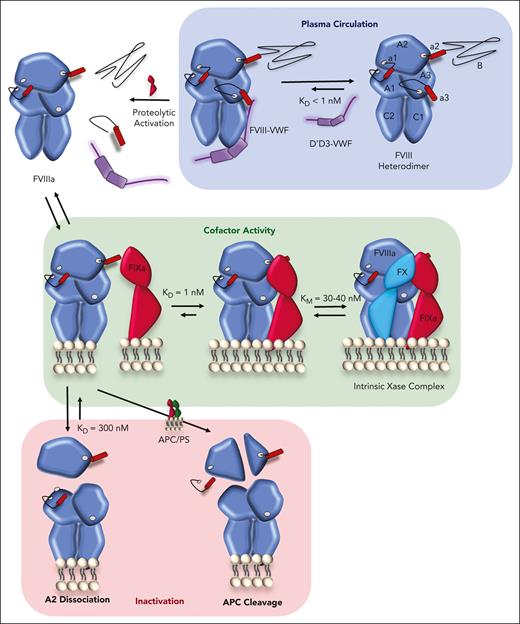

FVIII and FV are transported from the ER to the Golgi by the LMAN1-MCFD2 complex.20 Within the Golgi, FVIII undergoes additional posttranslational modifications, including glycan maturation and tyrosine sulfation. Single-chain FVIII also undergoes limited proteolysis at R1313 and R1648 within the B domain by proprotein convertases such as furin.21,22 These cleavages lead to heterodimer formation, composed of the heavy chain (A1-a1-A2-a2-B) and light chain (a3-A3-C1-C2) (Figure 2), which are held together through metal-ion dependent interactions between the A1 and A3 domains. The heterodimer is the predominant form of FVIII that circulates in plasma.23

BDD variants

The B domain is encoded entirely by exon 14 and comprises 40% of the protein. It is completely removed during activation and is not necessary for cofactor function.24 In B-domain deleted (BDD) FVIII variants, the B domain is replaced by short peptide linkers (Figure 1).21,22 BDD-FVIII variants were initially engineered to facilitate recombinant protein production but have been essential for the development of rAAV gene therapy because the size of the complementary DNA of full-length FVIII (7 kb) exceeds the packaging capacity of rAAV vectors (5 kb), whereas BDD-FVIII complementary DNA (4.4 kb) is sufficiently small to allow rAAV packaging. All the first-generation HA rAAV vectors use FVIII-SQ.4,21

Although BDD-FVIII has 20-fold higher messenger RNA levels than full-length FVIII from mammalian cell culture, there is only a twofold increase in secreted FVIII protein, equating to a 10-fold lower ratio of translated-to-secreted protein.16 How the B domain contributes to FVIII secretory efficiency is not well understood. The B domain is heavily glycosylated, with 8 occupied O-glycosylation sites and at least 6 to 14 occupied N-glycosylation sites out of 19 potential sites.25,26 These N-glycans facilitate the interaction of FVIII with the calnexin/calreticulin system within the ER9 and have been implicated in facilitating ER-to-Golgi transport by the LMAN1-MCFD2 complex.27 However, an in vitro study of LMAN1 variants with abrogated glycan binding still facilitated FVIII secretion, suggesting that N-glycan binding is not essential for ER-to-Golgi transport.28 Nonetheless, BDD-FVIII variants (N6 and V3) with linkers engineered to increase N-glycosylation demonstrated enhanced secretion and decreased aggregation compared with other BDD-FVIIIs in both mammalian cell cultures and after liver-directed gene transfer in mice.19,29-31 In FVIII-N6, the B domain is replaced by 226 amino acids from the N-terminal of the B domain (741-967) which encompasses 6 potential N-glycosylation sites (N757, N784, N828, N900, N943, and N963).29 FVIII-N6 is too large for rAAV packaging; as such, FVIII-V3 was designed by incorporating these 6 N-glycosylation sites and their flanking amino acids into FVIII-SQ (Figure 1).31 Although designed to retain 6 N-glycosylation sites, only 2 to 4 of these positions have been occupied by N-glycans in recent studies of plasma-derived FVIII.25,26 A 10 amino acid sequence within the B domain (788-SDLLMLLRQS-797) was recently suggested as an MCFD2-binding segment,32 but a subsequent study observed no difference in the secretion of FVIII with or without this sequence in mammalian cells.28

rAAV gene transfer in mice with FVIII-V3 had twofold higher FVIII levels than FVIII-SQ.31 FVIII-V3 is being investigated in an ongoing rAAV gene therapy trial (GO-8; NCT03001830). In the preliminary results, low-to-mild HA FVIII levels appeared stable for ≥4 years.33 Because of differences in other vector elements, cross-trial comparisons are not possible to rigorously determine whether FVIII-V3 is advantageous over FVIII-SQ in humans, as was seen in mice. This observed safety supports the potential of engineering B-domain linkers to enhance rAAV gene therapy.

We have shown that B-domain linkers designed to avoid interacting with furin also enhance the secretion of BDD-FVIII.34,35 A BDD-FVIII variant with a linker missing the canonical RXXR furin recognition motif (FVIII-ΔF; Figure 1) demonstrated threefold higher FVIII levels than FVIII-SQ in mammalian cell culture and after rAAV gene transfer in mouse and canine HA models, and the secretion advantage of FVIII-ΔF over FVIII-SQ was dependent on functional proprotein convertases.34 Further improvement in BDD-FVIII secretion was recently reported by eliminating a minor alternative cleavage site between 1657 and 1658 (FVIII-Δ3-SP/DE).35 It is not known whether avoiding interactions with furin similarly improves the secretion of full-length FVIII.

FVIII variants with improved secretion

Additional approaches to improve FVIII secretion efficiency (Table 1) have mostly focused on engineering A1 based on the observation that its replacement by the FV A1 domain improves FVIII secretion.18 Targeted mutagenesis identified FVIII-F309S, which has severalfold enhanced secretion in mammalian cell culture36 and after gene transfer in mice29 without compromising clotting activity. The enhanced secretion of FVIII-F309S was previously hypothesized to be secondary to decreased binding with BiP, but the recent recognition that the hydrophobic positions 291 to 310 are a likely nidus of FVIII aggregation17 suggests that the introduction of a polar side chain may inhibit aggregation.

For reasons that are not well understood, porcine (p) BDD-FVIII expresses approximately fivefold better than human (h) BDD-FVIII in mammalian cell cultures.37 Domain swapping studies between BDD-hFVIII and BDD-pFVIII supported that the increased secretion of pFVIII is due to differences in the A1 and A3 domains.38 FVIII-ET3 is a high-secretion human/porcine hybrid in which 125 porcine amino acids from the A1 and A3 domains are substituted in hFVIII along with a unique porcine B-domain replacement linker (Figure 1).38 In preclinical studies, FVIII-ET3 improved circulating FVIII across multiple gene-transfer approaches.39,40 FVIII-ET3 is currently incorporated into clinical trials of rAAV gene therapy (ASC618; NCT04676048) and ex vivo lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy (NCT05265767). The variant FVIII-X5 is a further iteration of this approach, in which only 5 porcine A1 amino acids are substituted in BDD-hFVIII.41 A computationally determined ancestral reconstructed FVIII variant (FVIII-An-53) demonstrated similar secretion as pFVIII and FVIII-ET3 in mammalian cell culture, and increased FVIII after rAAV gene therapy in mice.42 Taken together, these results suggest that hFVIII may have evolved to decrease the secretory efficiency.

Circulation, clearance, and role of vWF

FVIII circulates in a high affinity (dissociation constant [KD] <1 nM), noncovalent complex with its carrier von Willebrand factor (VWF), with 1:50 stoichiometry, such that >95% of FVIII is bound to VWF in plasma.43,44 The FVIII light chain (a3-A2-C1-C2) binds to the D’D3 region of VWF, as detailed in this issue.45 When not bound to VWF, FVIII has a sixfold reduction in its half-life. Most circulating FVIII is removed in complex with VWF through interactions between VWF and clearance receptors.44 Indeed, the clearance of FVIII via VWF-dominating interactions imposed a <20-hours half-life ceiling on first-generation EHL products.2 In a spectacular example of biology guiding therapeutic development, a next-generation EHL product Altuviiio (efanesoctocog alfa) achieved a 40-hour half-life in part by fusing FVIII with the VWF D'D3 domain to prevent complexing with endogenous VWF46; Altuviiio also incorporates a number of other half-life extending technology and circulates as a single-chain. VWF also limits FVIII membrane binding and protects it from membrane-bound proteases.47

Activation and cofactor activity

Conversion of the FVIII procofactor to the FVIIIa cofactor occurs after proteolytic cleavage (Figure 2). FVIII is liberated from VWF via thrombin cleavage at R1689. Additional cleavages at R372 and R740 generate the FVIIIa heterotrimer, which is comprised of a metal ion–linked A1/A3-C1-C2 dimer that is weakly associated with the A2 domain (KD ∼300 nM) by noncovalent A1 and A3 interactions.43,48 Once activated, FVIIIa binds FIXa with high affinity (KD, 1-2 nM).49,50 Recent structural studies have clarified that the FVIIIa/FIXa interface extends the length of FIXa and includes A2-a2 and A3-C1-C2 of FVIIIa,51,52 as reviewed in this issue.6

Cofactor FVIIIa enhances the catalytic activity of FIXa for FXa generation 104 to 106-fold (Table 2) by 3 overlapping mechanisms: (1) allosteric activation of FIXa53-58, (2) direct binding of FX59-62, and (3) facilitating colocalization of FIXa and FX to phospholipid membranes.63 The therapeutic development of alternative FIXa cofactors such as emicizumab1 and Mim864 that mimic some cofactor functions has helped clarify FVIIIa cofactor activity. Though the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) of the intrinsic Xase is useful for describing the biochemistry of the enzyme complex, it is important to recognize that the plasma concentration of FX is 180 nM (approximately fivefold the intrinsic Xase KM), suggesting that almost all intrinsic Xase complexes are saturated by FX substrate at physiological conditions.

FVIIIa binding to FIXa induces allosteric changes across multiple regions in FIXa, favoring a zymogen-to-protease transition of FIXa. FIXa without FVIIIa has an immature active site; there are several proposed models to describe the nature of this immaturity. One model suggests that substrate access to the active site is obstructed secondary to the positioning of Y99CT and F174CT (FIXa positions indicated with chymotrypsin numbering [CT]).51,52,73 Another model implicates W215CT as thermodynamically stabilizing a distorted active site.74 A2 binding FIXa at the 162CT-helix facilitates maturation of the active site, likely mediated through the 170CT-loop and the C168CT to C182CT disulfide bond.51,52,73 Direct A3 binding by the 99CT-loop FIXa may also contribute to this.51,52 The pivotal role of the A2 domain in the allosteric activation of FIXa is also supported by the observation that isolated A2 stimulates the rate of FXa generation severalfold (Table 2).54,58 The enhanced potency of FVIII-mimetic Mim8 compared with emicizumab is likely due to Mim8 binding to the FIXa 162CT-helix and recapitulating the A2-induced allosteric activation of FIXa.64 Supporting this model is the observation that the addition of FVIIIa heavy chain to the emicizumab-FIXa complex modestly further increases FXa generation.75

Assembly of FVIIIa with FIXa also increases FX substrate binding, potentially by binding an exosite on FVIIIa. Recent work demonstrating that FX noncompetitively competes with a FIXa peptidyl substrate indicates that FX binding to the intrinsic Xase is a multistep process, starting with exosite binding.76 This binding model complements previous studies suggesting a FX-binding site on FVIIIa that encompasses a1 (337-372),59 A2 (400-429),60 A3 (2007-2016),61 and C2 (2253-2270).62 FVIIIa likely promotes FIXa binding to phospholipid membranes.63 FVIII binds phospholipids severalfold better than FIXa binds phospholipids (0.2-2 nM KD vs 10 nM KD)77,78 and phospholipids enhanced the affinity for FVIIIa and FIXa by an order of magnitude.79

High-specific activity variants

Several high-specific activity FVIII variants (Table 1) have been characterized to varying degrees. The K1813A substitution in BDD-FVIII increased the specific activity by 2.4-fold and increased the in vivo hemostatic potency.67 K1813 is implicated in FIXa binding to the EGF2 domain and loop containing Y99CT.51,52 FVIII-K1813A had a 1.6-fold higher affinity for FIXa by surface plasmon resonance measurement; however, the rate of FVIIIa-K1813A FXa generation remained more than twofold higher than that of wild-type FVIIIa generation, even at saturating levels of FIXa (40 nM), suggesting that K1813A also may be facilitating the allosteric activation of FIXa, potentially by relieving the active-site obstruction by Y99CT. A FVIII variant (FVIII-K12) based on the canine FVIII sequence has sixfold higher specific activity than wild-type FVIII and also increased circulating FVIII activity after rAAV-based gene transfer in HA mice.68 FVIII-P290T has also been reported to have a modest increase in specific activity.66 The fact that multiple amino acid substitutions improve FVIII-specific activity suggests that wild-type human FVIII has not evolved to have optimized specific activity.

Inactivation and regulation

Inactivation of FVIIIa occurs via 2 processes: (1) spontaneous A2-dissociation and (2) activated protein C (APC) cleavage at R336 and R562 (Figures 1 and 2).43 These 2 downregulation pathways are not mutually exclusive, as engineered FVIII variants that are resistant to either A2-dissociation or APC cleavage have demonstrated enhanced in vivo potency.71,72,80 In isolation without binding partners, purified FVIIIa is inactivated within minutes due to A2-dissociation.81 However, the A2 domain is also stabilized by the incorporation of FVIIIa into intrinsic Xase.49 The physiologic significance of A2-dissociation is supported by numerous HA-causing FVIII variants with decreased A2 affinity.82 Studies investigating inactivation by APC have mostly examined the in vitro rate of procofactor FVIII cleavage, which occurs over an hour.83 FVIIIa is also protected from APC within intrinsic Xase. APC cleavage is facilitated by proteins S and FV, which are not comprehensively modeled in purified component assays.84 Indeed, we observed that an FVIII variant engineered to be wholly resistant to APC proteolysis due to R336Q and R562Q substitutions (FVIII-QQ) demonstrated enhanced in vivo potency across multiple hemostatic injuries in mice72; these studies support that APC does have physiologic relevance in FVIII/FVIIIa regulation. This enhanced potency of FVIII-QQ was dependent on APC activity, as inhibition of APC normalized the in vivo activity of FVIII-QQ to that of wild-type FVIII. Taken together, these studies suggest that in vivo, FVIIIa after activation enters a complicated kinetic scheme (Figure 2) between A2-dissociation, APC cleavage, and intrinsic Xase formation.

Inactivation-resistant FVIII variants

The substitution of negatively charged amino acids for hydrophobic amino acids at the A1/A2 (D519V) or A2/A3 (E665V or E1984) interface dramatically decreases A2-dissociation.85 The double-substituted variant FVIII-VV (D519V/E665V) exhibits a sevenfold decrease in the rate of FVIIIa inactivation86 and a twofold increase in in vivo hemostatic activity after injury in HA mice.71 A2-dissociation can also be inhibited by the engineering of a disulfide bond connecting the A2 domain with the A3 domain through amino acid substitutions Y664C and T1826C or M662C and D1828C; these disulfide bond stabilized FVIII variants demonstrated twofold higher specific activity as well as increased in vitro thrombin generation.70 FVIII-K1813A also demonstrated a twofold decrease in A2-dissociation.67 The combined triple-substituted variant (D519V/E665V with K1813A) exhibits higher in vitro and in vivo hemostatic potency than single- or double-substituted variants.87 Despite these encouraging results, FVIII variants with engineered A2 stabilization have not been evaluated in preclinical gene therapy studies.

In contrast, APC-resistant FVIII-QQ has demonstrated a fivefold enhanced hemostatic potency in HA mice when administered as protein72 or rAAV gene therapy.15 FVIII-IR8 is a BDD variant designed to be wholly inactivation-resistant, limiting both A2-dissociation and APC cleavage, but with reduced VWF affinity, likely due to the absence of the a3 domain.69 IR8 exhibited fivefold higher specific activity than wild-type FVIII.69 In vivo studies in HA mice suggested increased hemostatic efficacy of IR8 compared with that of wild-type FVIII after gene transfer.30,88 Preliminary results of an alternative wholly inactivation-resistant FVIII variant that combines FVIII-QQ with FVIII-VV demonstrated 12-fold enhanced hemostatic function.80 Collectively, these studies of gain-of-function variants suggest that both mechanisms of FVIIIa regulation have physiologic relevance and could be exploited to enhance FVIII function for therapeutic benefit.

Evolutionary implications of gain-of-function variants

The multiple gain-of-function FVIII variants (Table 1) highlight that hFVIII has not evolved to maximize its procoagulant activity. A similar conclusion can be made about FIX, also based on gain-of-function variants.5,89,90 We speculate that the physiological activity of the human intrinsic Xase complex is an example of the Goldilocks principle of biochemical adaptation:91 intrinsic Xase has evolved to be “just right” to prevent bleeding but not “too hot” to cause thrombosis.92 Others have suggested that the evolutionary constraints of thrombosis-related mortality during bipedal specialization may have specifically limited human intrinsic Xase complex activity compared with other mammalian orthologs.42 However, this speculation assumes that a higher FVIIIa cofactor function results in higher global procoagulant activity rather than counteracting decreases in other components of the hemostatic system. Indeed, a recent quantification of distinct mechanical attributes of platelets across mammalian species identified notable differences in the specific attributes but only minimal differences in clot contraction, suggesting that the specific mechanical differences compensate for each other to generate similar global functions.93 Regardless, nonhuman orthologs have been a fertile source of bioengineering approaches for variant development, although this strategy requires attention to immunogenicity concerns.5

Immunogenicity of FVIII

Although the mechanisms driving FVIII immune responses are incompletely understood, FVIII-responsive B-cell activation relies on CD4+ T cells, which in turn are dependent on FVIII peptide presentation by major histocompatibility complex-II molecules. At least 25% of healthy donors have nonneutralizing antibodies against FVIII94 and FVIII-reactive CD4+ T cells.95 FVIII uptake in the spleen by marginal zone B cells is critical for initiating FVIII immune responses,96 although recent work suggests that a relay system between conventional dendritic cells, macrophages, and marginal zone B cells may be needed for FVIII-responsive T-cell activation.97 Increased levels of BAFF, which support B-cell differentiation, correlate with inhibitors in patients, and inhibition of BAFF promotes FVIII tolerance in HA mice.98 Pre-existing FVIII-responsive B cells can be suppressed by PD-L1+ regulatory T cells.99 Here, we focused on investigations of FVIII immunodominant epitopes that are relevant when considering the risk of inhibitor formation with FVIII modifications. For therapeutic use, the advantages of gain-of-function variants must outweigh the risk of immunogenicity.5

B-cell epitopes defined by antibody-binding sites are outlined in Table 3. Early studies mapping the epitope of samples from inhibitor patients identified residues 338 to 536 in A2,100 2170 to 2327 in C2,100 and 1690 to 2192 in A3-C1.101 Although antibodies to all domains have now been described,102 the preponderance of anti-A2 and anti-C2 antibodies has held. Most inhibitor patients have antibodies against ≥2 domains.103

C2 domain

Human T cells demonstrate an immunodominant epitope at 2291 to 2330, which partially overlaps with the antibody-binding sites.107 Additional epitopes from healthy subjects and noninhibitor patients at 2191 to 2210 in C2 suggest that this may downregulate T-cell responses.107 The B-cell epitopes of the C2 domain are defined by 5 monoclonal antibody (mAb) groups that inhibit either VWF/phospholipid binding (“classical”) or FVIII activation by delaying release from VWF (“nonclassical”).104 The antibody epitope for the nonclassical antibody G99 surrounds Lys2227 with complex interactions and the classical murine mAbs 3E6 and I109 surround Met2199 and Leu2251 loop.108 The binding interface of the human monoclonal anti-C2 antibody BO2C11 overlaps with that of 3E6, whereas 3E6 and G99 bind to the opposite surfaces of C2.109

A2 domain

Analysis of CD4+ T-cell binding to FVIII A2-peptide sequences from patients with HA with/without inhibitors and healthy donors identified promiscuous binding in both sample cohorts at residues 371 to 400, although the response was stronger in those with inhibitors. Additional responses to residues 411 to 430 and 671 to 690 were only present in the inhibitor patients.110 These residues are solvent-exposed and either flanked by or part of the unstructured loops.

Using murine hybridoma models, dominant B-cell epitopes on A2 are defined by 8 mAb groups at amino acids that include, 484 to 508 (group A), 541 to 604 (group B), 444 to 648 (group C), and 604 to 740 (groups D and E).105 These antibodies inhibit FXa generation and thrombin cleavage. Murine mAb groups D and E have overlapping epitopes with T-cell studies and the binding site for the human mAb NB11B2 (379-456)111 overlaps with the immunodominant T-cell epitopes at 371 to 400 and 411 to 430.

A3-C1 domains

For unclear reasons, healthy subjects have more vigorous and heterogeneous CD4+ T-cell responses to the A3 domain. The highest immunogenicity index for peptides spanning residues 1801 to 1820 was seen in both healthy donors and inhibitor patients. Smaller responses to 1691 to 1710 and 1941 to 1960 were seen in inhibitor patients than in healthy controls.112 These residues align with prior findings on immunodominant T-cell epitopes in terms of structural flexibility and accessibility. The A3 domain contains dominant antibody-binding sites at residues 1803 to 1818, which inhibit FIX/FIXa binding.101,111

Extensive mapping of T-cell epitopes to C1 has not yet been conducted. Derivation of polyclonal T-cell lines from inhibitor patients identified a dominant epitope at 2098 to 2112, which spans 2 surface-exposed beta-strands.113 Murine hybridoma studies have shown the proximity of the B- and T-cell epitopes in C1. The C1 domain has 3 mAb-binding groups defined by 2A9 (group A, amino acids 2065, 2070, 2150-2156, and 2110-2112), B136 (group B, amino acids 2077-2084), and the human mAb KM33 overlaps with these sets (group AB) with discontinuous binding sites at 2090 to 2094 and 2158 to 2159 interrupting membrane binding by the C1 loop.106 Group A antibodies decrease VWF binding and FVIII uptake by dendritic cells, and are weak inhibitors compared with group B and AB antibodies, which interfere with VWF/phospholipid binding.

Deimmunization

The identification of T- and B-cell epitopes, especially those with overlapping binding sites, may inform on the engineering of variants with reduced immunogenicity. Modifications at residues 2196 and 2199 resulted in decreased binding by BO2C11 and decreased activation of T cells in an inhibitor patient.114 Modification of computationally predicted C2 T-cell epitopes decreased FVIII immune responses in humanized HLA-DR mice.115 Modification of the N-linked glycosylation C1 site (N2118Q) decreased inhibitor responses and T-cell proliferation after liver-directed gene transfer in HA mice.116 Together, these studies highlight the therapeutic potential of understanding the structural basis of FVIII immune responses for therapeutic development. However, a more comprehensive understanding of HLA types in inhibitor patients is necessary to better inform T-cell deimmunization approaches.

Immunogenicity after gene therapy

The hFVIII alloimmune response in HA has, until recently, been exclusively investigated after exposure to FVIII protein. Hepatocyte-directed FVIII gene therapy in HA mice and dogs with and without pre-existing inhibitors is tolerogenic, likely due to (1) the unique bias of the liver environment toward immune tolerance and (2) the continuous uninterrupted exposure of transgene-FVIII antigen.117,118 These preclinical studies suggest that several parameters of hepatocyte-directed FVIII gene transfer are important for this tolerogenic effect, including the absence of liver inflammation117 and initial FVIII exposure rate.119

It is not clear how much of the understanding of FVIII protein alloimmunity is applicable to FVIII gene transfer.5 Low-level and transient humoral and cellular anti-FVIII immune responses were recently reported in HA rAAV gene therapy recipients who had no history of inhibitors, although some exhibited laboratory evidence of pre-existing anti-FVIII immune responses.120 There were no clinical ramifications for these findings and they are probably on par with the descriptions of FVIII immunity in healthy donors.94,95 To date, no HA gene therapy recipient has developed a persistent inhibitor. Initial rAAV gene therapy clinical trial (NCT04684940) results for HA with inhibitors were recently presented.121 Although more clinical data are needed, hepatocyte-directed gene transfer appears tolerogenic.

Conclusions

Remarkable innovation in HA therapeutics have been predicated on an understanding of FVIII biology. Despite these advancements, the ultimate goal of HA therapy of normalizing hemostasis and optimizing health and well-being with minimal treatment burden remains aspirational,122 especially considering that global access to therapies is severely constricted. Gene therapy holds the promise of meeting this goal after a single therapeutic administration; however, current approaches have only achieved high levels that decline or durable low-mild FVIII levels. Numerous gain-of-function FVIII variants (Table 1) have already been identified, highlighting that wild-type FVIII may be enhanced to overcome the current limitations of gene transfer. These or yet unidentified variants may allow for a multidecade-high hemostatic activity, redeeming the promise of gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

All authors are supported by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Frontiers Program. B.J.S.-J. acknowledges additional research funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant HL158781).

Authorship

Contribution: B.J.S.-J., B.S.D., and L.A.G conceptualized, wrote, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.J.S.-J. and L.A.G. hold patent rights for gain-of-function FVIII variants. L.A.G. receives licensing fees from Asklepios BioPharmaceutical. B.S.D. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Benjamin J. Samelson-Jones, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 3501 Civic Center Blvd, 5028 Colket Translational Research Center, Philadelphia, PA 19104; email: samelsonjonesb@chop.edu.

References

Author notes

B.J.S.-J., B.S.D., and L.A.G. contributed equally to this study.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.