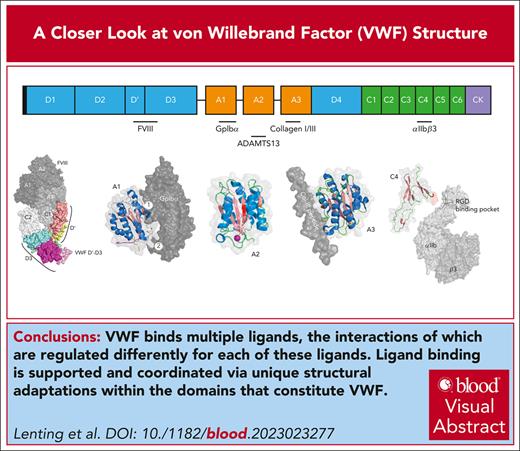

Visual Abstract

von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a multimeric protein consisting of covalently linked monomers, which share an identical domain architecture. Although involved in processes such as inflammation, angiogenesis, and cancer metastasis, VWF is mostly known for its role in hemostasis, by acting as a chaperone protein for coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) and by contributing to the recruitment of platelets during thrombus formation. To serve its role in hemostasis, VWF needs to bind a variety of ligands, including FVIII, platelet-receptor glycoprotein Ib-α, VWF-cleaving protease ADAMTS13, subendothelial collagen, and integrin α-IIb/β-3. Importantly, interactions are differently regulated for each of these ligands. How are these binding events accomplished and coordinated? The basic structures of the domains that constitute the VWF protein are found in hundreds of other proteins of prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. However, the determination of the 3-dimensional structures of these domains within the VWF context and especially in complex with its ligands reveals that exclusive, VWF-specific structural adaptations have been incorporated in its domains. They provide an explanation of how VWF binds its ligands in a synchronized and timely fashion. In this review, we have focused on the domains that interact with the main ligands of VWF and discuss how elucidating the 3-dimensional structures of these domains has contributed to our understanding of how VWF function is controlled. We further detail how mutations in these domains that are associated with von Willebrand disease modulate the interaction between VWF and its ligands.

Introduction

von Willebrand factor (VWF) is among the largest proteins circulating in plasma. Although recognized to participate in processes such as inflammation, angiogenesis, and cancer metastasis, VWF is predominantly known for its role in hemostasis.1-3 Indeed, its deficiency or dysfunction is associated with bleeding complications in a disorder known as von Willebrand disease (VWD).4 VWF is synthesized as a single-chain polypeptide with a distinct domain structure: D1-D2-D’D3-A1-A2-A3-D4-C1-C2-C3-C4-C5-C6-CK (with CK referring to cysteine knot domain; Figure 1).5 Posttranslational processing includes the removal of the D1-D2 region (also known as the VWF propeptide) and the generation of heterogeneously sized multimers via the formation of intermolecular disulfide bridges in the C-terminal CK domain and the N-terminal D’D3 region.6

Domain structure of VWF. Structurally defined domain architecture of VWF, based on annotation by Zhou et al.5 Depicted are approximate binding sites for the ligands discussed in this review.

Domain structure of VWF. Structurally defined domain architecture of VWF, based on annotation by Zhou et al.5 Depicted are approximate binding sites for the ligands discussed in this review.

Regarding its role in hemostasis, VWF will need to interact with various ligands, including coagulation factor VIII (FVIII), platelet-receptor glycoprotein Ibα (GpIbα), VWF-cleaving protease ADAMTS13, subendothelial collagen, and integrin αIIbβ3 (Figure 1).1 Importantly, the interaction with each of these ligands is regulated in a different manner. For instance, although VWF should bind FVIII with high affinity in the circulation, it needs to avoid interacting with GpIbα until platelet recruitment becomes relevant. The beauty of the VWF molecule is that the keys to unlock different levels of regulation are directly present in its structure. At first glance, the domains that compose VWF are not unique, because the general folding of the A, C, CK, and D domains can be found in many proteins in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. However, several distinct adjustments have been incorporated into the VWF structure to meet the necessary requirements regarding ligand-specific interactions. The most “famous” adaptation is the unusually large size of VWF. Its large size makes VWF susceptible to conformational changes under the influence of hydrodynamic forces, which is 1 mechanism to control VWF function.7,8

When reviewing VWF structural studies performed over the last 2 decades, the secrets of this fascinating molecule have slowly been unraveled, helping us to recognize how complexation between VWF and its ligands is regulated. In this review, we will, therefore, concentrate on the main ligands of VWF and discuss how elucidating the 3-dimensional structures of VWF domains, generally in complex with its ligands, has contributed to our understanding of how VWF function is controlled. In addition, these insights also improved our knowledge on why certain mutations are associated with VWF dysfunction and subsequent bleeding tendencies.

FVIII binding to the D′D3 region

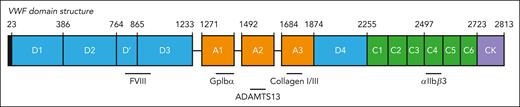

VWF contains 4 full D assemblies and another partial one, which together encompass nearly 60% of the total amino acid content. A closer look at these D assemblies has revealed the presence of 4 distinct structures: a von Willebrand D (VW-D) domain, a C8-fold, a trypsin inhibitor-like (TIL) structure, and an E module.5 These structures can be found in the D1, D2, D3, and D4 assemblies, whereas the D’ segment contains only the TIL structure and the E module. Two of the D assemblies, that is the D’D3 region (residues Ser764-Thr1233), are located N-terminally in the mature subunit and contribute to the multimerization process by making intersubunit cysteine bonds with a D’D3 region of another VWF molecule.5,9-11 Besides its role in VWF multimerization, the D’D3 region is also critical to the interaction between VWF and FVIII.12 VWF is a necessary chaperone protein for FVIII, protecting it from rapid clearance and proteolytic degradation. Indeed, the absence of VWF is associated with strongly reduced FVIII levels.13 Expression of the dimeric D’D3 portion in VWF-deficient mice fully normalized FVIII levels, showing that this region harbors all the information to bind FVIII.14 Notably, the affinity of the FVIII/VWF interaction is unusually high (KD ≈ 0.5 nM), allowing >95% of FVIII to circulate complexed with VWF.13,15-17

Although classic mutagenesis studies identified amino acids involved in FVIII binding,18-21 the availability of FVIII and VWF structures has provided detailed insight into their interaction. First, in 2 back-to-back publications, Chiu et al and Yee et al used negative-stain and single-particle electron microscopy to generate low-resolution images of the complex between FVIII and D’D3.22,23 They showed that the FVIII light chain (a3-A3-C1-C2) is enveloped by the D’D3 region, with the D3 assembly interacting with the C1-C2 domains and the D’ segment binding to the a3-A3 portion. Another study confirmed the relevance of the D’ segment in binding FVIII and used hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry and mutational analysis to identify the D’ Arg782-Cys799 segment as part of the FVIII-binding interface.24 A comprehensive view of the D’D3/FVIII complex was obtained by using a FVIII-D’D3 fusion protein, designated BIVV001 (now renamed efanesoctocog alfa).25 By combining cryogenic electron microscopy and existing structures of FVIII and the D’D3 region, a high-resolution (2.9 Å) visualization of the D’D3/FVIII complex was generated (Figure 2A-B). The substructures of the D’D3 are distinguishable, with the C8-3–fold binding to the bottom of the FVIII C2 domain and the VW-D-3 domain to the FVIII C1 domain. Furthermore, the TIL’ structure interacts with the FVIII C1 and A3 domains, including the acidic a3 region. More specifically, the acidic FVIII residues Asp1676, Asp1678, and Asp1681 interact with TIL’ residues Arg820, Arg826, and Arg768, respectively, whereas sulfated FVIII-residue Tyr1680 interacts directly with TIL’-residue Arg816 (Figure 2A-B).25

Structure of the D’D3/FVIII complex. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF D’D3/FVIII complex derived from PDB-deposit 7KWO.25 Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Cartoon impression of the complex, highlighting VWF D’D3 subdomains. Principal interaction interfaces are indicated by arrows. The direct interaction between sulfated FVIII-residue Tyr1680 and VWF D’-residue Arg816 is shown as well. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the D’D3 subdomains. Circles indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with reduced FVIII binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2N. Figure panel B adapted from Fuller et al.25

Structure of the D’D3/FVIII complex. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF D’D3/FVIII complex derived from PDB-deposit 7KWO.25 Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Cartoon impression of the complex, highlighting VWF D’D3 subdomains. Principal interaction interfaces are indicated by arrows. The direct interaction between sulfated FVIII-residue Tyr1680 and VWF D’-residue Arg816 is shown as well. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the D’D3 subdomains. Circles indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with reduced FVIII binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2N. Figure panel B adapted from Fuller et al.25

The detailed structure of the D’D3/FVIII complex explains many of the mutations that impair FVIII binding. For example, mutations within VWF in the Arg782-Cys799 region and at Arg816 reduce FVIII binding and are known for their association with VWD-type 2N (Figure 2C).26-28

A relevant question is whether FVIII binding is dependent on multimerization. Dimeric VWF, which is the only natural VWF species that lacks dimerized N-termini, has a fivefold lower affinity for FVIII than multimeric VWF.29 This suggests that covalent bonding between VWF N-termini enhances FVIII binding. Because VWF-FVIII–binding studies comparing preparations enriched in low and high molecular weight multimers identified similar affinities for FVIII; additional multimerization does not seem to further improve FVIII binding.16 Indeed, the FVIII/VWF ratio remains relatively unchanged in patients characterized by a loss of high molecular weight multimers.30

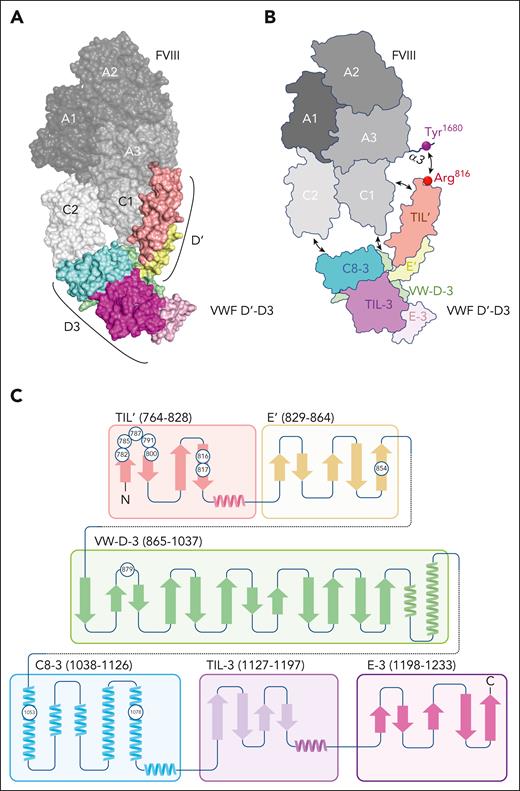

GpIbα binding to the A1 domain

Adjacent to the D’D3 region is the A1 domain (residues Tyr1271-Asp1459), with the N- and C-termini being connected by a disulfide bridge (Cys1272-Cys1458). This domain shares structural resemblance with the A2 and A3 domains in a von Willebrand A (VWA)–fold that is widely spread among protein families in eukaryotes and prokaryotes.31 The general structure consists of central hydrophobic β-sheets flanked by amphipathic α-helices, making up a Rossmann-like fold (Figure 3A).34 The A1 domain mediates the binding of VWF to the platelet-receptor GpIbα, and its crystal structure was elucidated in the 1990s.35,36 Solving the structure of the VWF/GpIbα complex was hampered because both proteins do not interact spontaneously, because their association is shear force dependent.37 By using fragments containing gain-of-function mutations that facilitate complexation, however, Huizinga et al solved the structure of the A1 domain bound to the N-terminal domain of GpIbα.32 Additional structures of VWF/GpIbα complexes have since been produced using both wild-type and other gain-of-function variants.38,39

Structure of the A1/GpIbα complex. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF A1 domain/GpIbα complex derived from PDB-deposit 1M1O.32 N- and C-terminal flanking peptide (N-AIM and C-AIM) are colored in purple and orange, respectively; 1 and 2 refer to interactive sites 1 and 2, respectively. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Three-dimensional representation of the A1 domain in complex with VHH81 (a sequence identical analog of caplacizumab; pale green) derived from PDB-deposit 7A6O.33 VHH81/caplacizumab stabilizes the conformation of the N-AIM/C-AIM interaction, thereby preventing binding of GpIbα to interactive site 2. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the A1 domain. Circles indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with increased GpIbα binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2B. Squares indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with reduced GpIbα binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2M. Note, in the 3-dimensional space, the N- and C-terminal ends of the A1 domain are in close vicinity via a disulfide bridge between Cys1272 and Cys1458.

Structure of the A1/GpIbα complex. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF A1 domain/GpIbα complex derived from PDB-deposit 1M1O.32 N- and C-terminal flanking peptide (N-AIM and C-AIM) are colored in purple and orange, respectively; 1 and 2 refer to interactive sites 1 and 2, respectively. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Three-dimensional representation of the A1 domain in complex with VHH81 (a sequence identical analog of caplacizumab; pale green) derived from PDB-deposit 7A6O.33 VHH81/caplacizumab stabilizes the conformation of the N-AIM/C-AIM interaction, thereby preventing binding of GpIbα to interactive site 2. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the A1 domain. Circles indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with increased GpIbα binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2B. Squares indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with reduced GpIbα binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2M. Note, in the 3-dimensional space, the N- and C-terminal ends of the A1 domain are in close vicinity via a disulfide bridge between Cys1272 and Cys1458.

The VWF/GpIbα complex involves 2 main interactive sites, 1 containing A1-domain helix α3, loop α3β4, and strand β3 (interactive site 1) and a second one containing A1-domain loops α1β2, β3α2, and α3β4, located at the bottom face of the A1 domain (interactive site 2; Figure 3A-B). The structure of the complex revealed insights into how different mutations affect binding between both proteins. First, mutations in the A1 domain or in GpIbα resulting in a loss of function (associated with VWD-type 2M or Bernard-Soulier syndrome, respectively) are found within the respective interactive sites.32 Second, gain-of-function mutations in GpIbα known to provoke platelet-type VWD were found within a unique 16-residue β-hairpin conformation that penetrates into interactive site 1 of the A1 domain. In the unbound state, this region adopts a disordered or α-helical state, whereas the β-hairpin structure is favored for VWF binding.32,38 Mutations in this region (eg, Met239Val) stabilize the β-hairpin structure, causing spontaneous binding of GpIbα to VWF.

Surprisingly, none of the gain-of-function mutations within the A1 domain associated with VWD-type 2B are located within either interactive site, suggesting that other regions within the A1 domain are involved in regulating GpIbα binding. Insight into the underlying mechanism was obtained when recombinant A1-domain fragments with differently sized flanking peptides were compared for GpIbα binding.40,41 The shorter the flanking peptide, the more efficient the A1 domain binds GpIbα. The molecular basis by which the flanking peptides control A1-GpIbα interactions was unraveled by Li et al.33,42,43 They demonstrated that residues Gln1238-His1268 at the N-terminus of the A1 domain interact directly with residues Leu1460-Asp1472 at the C-terminus of the A1 domain. This structure is referred to as autoinhibitory module (AIM), and it blocks access of GpIbα to interactive site 2 at the bottom of the A1 domain.33,42 Under the pressure of hydrodynamic forces, the AIM peptides dissociate, thereby exposing GpIbα-interactive site 2 (Figure 3A-B).43 It is noteworthy that ristocetin, an antibiotic that induces VWF/GpIbα binding, is known to interact with peptides Cys1237-Pro1251 and Glu1463-Asp1472, both of which are contained within the AIM.44 It seems conceivable that ristocetin destabilizes the AIM structure to induce GpIbα binding. Importantly, mutations known to be associated with VWD-type 2B are generally located within or near the AIM and disrupt the interaction between both peptides, providing an explanation for spontaneous binding of these mutants to GpIbα (Figure 3C).

Together, these studies show that conformational changes in the immediate surrounding of the A1 domain control its interactions with GpIbα. Interestingly, a number of nanobodies have been described that support this notion. First, Hulstein et al described an A1 domain–directed nanobody, named AU-VWFa-11, that only binds VWF in a GpIbα-binding conformation.45 This nanobody has been used to determine the active conformation of VWF in a spectrum of diseases.46 Another example is caplacizumab, a bivalent nanobody that inhibits VWF-GpIbα interactions and is approved for treatment of thrombocytopenic thrombotic purpura.47,48 A monovalent variant of caplacizumab (designated VHH81) was used to make a cocrystal with the A1 domain. VHH81 binds to and stabilizes the AIM structure, thereby preventing its dissociation under shear stress (Figure 3B). As such, exposure of interactive site 2 and subsequent GpIbα binding are inhibited.33 Another nanobody designated 6D12 also binds to the AIM but has the opposite effect of caplacizumab: 6D12 promotes dissociation of the AIM peptides, converting VWF into an active GpIbα-binding conformation.43 Apparently, nanobodies are valuable tools to monitor conformational changes in general and in VWF in particular, and another example will be discussed when addressing the VWF A3 domain.

Knowing that shear forces are needed to unblock GpIbα-interactive sites, the question follows whether this process is multimer dependent. In the 1980s, Chopek et al demonstrated that GpIbα binding is strictly multimer-size dependent, in that low molecular weight multimers are too small to support GpIbα-dependent platelet adhesion.49 This effect is particularly visible in patients displaying impaired multimerization and associated bleeding complications (VWD-type 2A). It is assumed that unfolding of VWF is size dependent, with larger multimers being more sensitive to hydrodynamic forces than smaller multimers.7,8

ADAMTS13 binding to the A2 domain

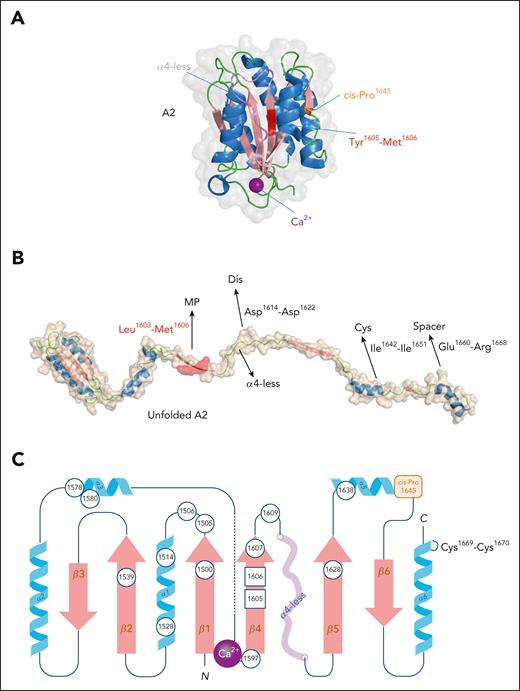

The A2 domain (residues Arg1492-Ser1671) plays a specific role in regulating VWF function and multimer size. Structurally, the A2 domain differs from other VWA domains by lacking the disulfide bridge that connects the N- and C-terminal ends of the domain.50 This allows the A2 domain to have a more flexible structure and adapt its conformation when exposed to hydrodynamic forces, a necessary capacity knowing that proteolytic regulation of VWF multimeric size occurs via hydrolysis of the Tyr1605-Met1606 peptide bond by the metalloprotease ADAMTS13.50

The crystal structure of the A2 domain revealed a number of relevant differences compared with other members of the VWA family (Figure 4A).50 First, the central α4-helix is absent in the A2 domain and is replaced by a loop lacking in secondary structure (referred to as α4-less loop) that is about 6 Å away from the ADAMTS13 cleavage site (Figure 4A). Second, the A2 domain contains a unique vicinal disulfide bond between residues Cys1669-Cys1670.50 Third, a distinctive Ca2+-binding site is present, coordinated by residues in the β1-sheet (Asp1498), the α3-helix (Asp1596 and Arg1597), and the α3β4-loop (Ala1600 and Asn1602; Figure 4A).51,52 Finally, an unusual cis-Pro residue is present at position 1645 (Figure 4A).50 Each of these features seems to be a functional adaptation regulating exposure of the Tyr1605-Met1606 cleavage site. Regarding the α4-less loop, it reduces access of ADAMTS13 to the scissile bond in the folded state, whereas its flexible nature allows it to promptly move away from Tyr1605-Met1606 during the unfolding of the A2 domain.50 Simultaneously, this loop may refold back over the β4-strand less rapidly than it would if it were an α-helix structure, leaving sufficient time for ADAMTS13 to cleave its target.50 Furthermore, the cis-Pro1645 is suspected to delay refolding of the A2 domain.50 The vicinal disulfide bond adds rigidity to the C-terminal end of the A2 domain, increasing the energetic barrier for the domain to unfold. Similarly, the Ca2+ site contributes to the stability of the A2-domain structure, resulting in further resistance to unfolding.51,52 Removing the Ca2+-binding site or the vicinal disulfide bridge indeed provokes premature unfolding and increases sensitivity to proteolysis by ADAMTS13.52,53 In contrast, introducing an artificial covalent connection between the β1- and β2-sheets impairs unfolding and prevents ADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis.54

Structure of the A2 domain. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF A2 domain derived from PDB-deposit 3ZQK.51 The Tyr1605-Met1606 scissile bond is in red, the α4-less loop in violet, the unique Ca2+-ion is in purple, and cis-Pro1645 is in orange. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Cartoon impression the A2 domain in its unfolded conformation. Once unfolded, the A2 domain exposes several interactive sites for ADAMTS13, allowing the Tyr1605-Met1606 scissile bond to be hydrolyzed by the ADAMTS13 metalloprotease domain (MP). Other interactive sites involve the α4-less loop residues Asp1614-Asp1622 interacting with the disintegrin domain (Dis), the α5-helix/β6-sheet region Ile1642-Ile1651 binding to the cysteine-rich domain (Cys), and the α6-helix residues Glu1660-Arg1668 associating to the spacer domain of ADAMTS13. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the A2 domain including the Ca2+ binding site and the vicinal disulfide bridge, both being unique to the A2 domain. The Tyr1605-Met1606 scissile bond is located in the middle of the β4-strand. Circles indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with increased ADAMTS13-mediated degradation in patients with group 2 von Willebrand disease-type 2A. In contrast to the A1 and A3 domains, the A2 domain lacks a disulfide bridge that connects the N- and C-termini of this domain.

Structure of the A2 domain. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF A2 domain derived from PDB-deposit 3ZQK.51 The Tyr1605-Met1606 scissile bond is in red, the α4-less loop in violet, the unique Ca2+-ion is in purple, and cis-Pro1645 is in orange. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Cartoon impression the A2 domain in its unfolded conformation. Once unfolded, the A2 domain exposes several interactive sites for ADAMTS13, allowing the Tyr1605-Met1606 scissile bond to be hydrolyzed by the ADAMTS13 metalloprotease domain (MP). Other interactive sites involve the α4-less loop residues Asp1614-Asp1622 interacting with the disintegrin domain (Dis), the α5-helix/β6-sheet region Ile1642-Ile1651 binding to the cysteine-rich domain (Cys), and the α6-helix residues Glu1660-Arg1668 associating to the spacer domain of ADAMTS13. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the A2 domain including the Ca2+ binding site and the vicinal disulfide bridge, both being unique to the A2 domain. The Tyr1605-Met1606 scissile bond is located in the middle of the β4-strand. Circles indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with increased ADAMTS13-mediated degradation in patients with group 2 von Willebrand disease-type 2A. In contrast to the A1 and A3 domains, the A2 domain lacks a disulfide bridge that connects the N- and C-termini of this domain.

Once unfolded, the A2 domain contains an extended interactive site for several domains that are contained within ADAMTS13. In fact, the complete interaction interface extends beyond the A2 domain and also involves regions within the D4-CK fragment of VWF,55 an aspect which will not be discussed in this review. Within the unfolded A2 domain, the β4-sheet residues Leu1603-Met1606 are accessible for the active site of the ADAMTS13 metalloprotease domain, permitting hydrolysis of the Tyr1605-Met1606 scissile bond.56,57 For this process to proceed efficiently, the α4-less loop residues Asp1614-Asp1622 interact with the disintegrin domain, the α5-helix/β6-sheet region Ile1642-Ile1651 binds to the cysteine-rich domain, and the α6-helix residues Glu1660-Arg1668 associate with the spacer domain of ADAMTS13 (Figure 4B).56,57

Given the strict control of the A2-domain conformation, it is unsurprising that this regulation can be disturbed by a wide range of mutations (Figure 4C). For example, some mutations will promote exposure of the otherwise buried cleavage site (such as Met1528Val or Glu1638Lys), whereas others will delay the refolding of the A2 domain (eg, Arg1597Trp), prolonging the time that ADAMTS13 can cleave the Tyr1605-Met1606 bond.58 These mutations ultimately result in increased ADAMTS13–mediated VWF degradation and are referred to as group 2 VWD-type 2A mutations. Patients carrying such mutations display a loss of high molecular weight multimers and an increased risk of bleeding. Increased VWF degradation is also common in VWD-type 2B.59

VWF degradation is further enhanced upon binding of FVIII or GpIbα, suggesting that these ligands modulate the unfolding or refolding of the A2 domain.60,61 The susceptibility to ADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis is multimer-size dependent. Larger multimers unfold more easily than smaller multimers when exposed to irregular flow, allowing ADAMTS13 to attack the proteolysis site.7,8 This feature is particularly visible in patients manifesting disturbed blood flow; for example, in patients with severe aortic stenosis or those receiving mechanical circulatory support. These patients are often characterized by increased VWF degradation, with a visible loss of the high molecular weight multimers.62,63

Collagen binding to the A3 domain

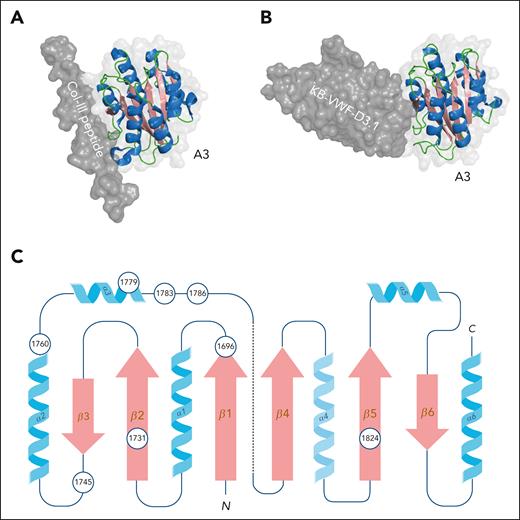

The A3 domain spans residues Pro1684-Ser1873, containing a disulfide bridge that connects the N- and C-terminus of this domain (Cys1686-Cys1872). The A3 domain mediates binding to collagen types I and III.64 The crystal structure of the A3 domain was solved independently by 2 groups, allowing them to confirm the typical VWA-fold with alternating α-helices and β-sheets.65,66 A potential collagen-binding site involving the β3-sheet and the α2- and α3-helices was identified via extensive mutational analysis.67 The identification of the exact collagen interactive site was facilitated when a collagen III peptide was identified that specifically binds to VWF.68 This peptide was used to generate a cocrystal containing the A3-domain/collagen peptide complex (Figure 5A-B).69 The collagen peptide indeed binds to the region encompassing the β3-sheet and the α2/α3-helices, covering a surface ∼24 Å wide and 30 Å long. In total, 14 amino acids within the A3 domain have been identified to directly interact with the collagen peptide.69 Analysis of the complex also allowed for the identification of complementary amino acids in collagen I and III involved in binding to VWF. Particularly, the structure has helped to explain why both collagen I and III are able to bind VWF at the same site despite their structural differences (for details see Brondijk et al69).

Structure of the A3 domain/collagen complex. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF A3 domain in complex with a collagen III triple-helical peptide derived from PDB-deposit 4DMU.69 Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Three-dimensional representation of nanobody KB-VWF-D3.1 docked onto the A3 domain.70 The nanobody’s binding site overlaps the interactive surface involved in collagen binding. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the A3 domain. Circles indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with reduced collagen binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2M. Note, in the 3-dimensional space, the N- and C-terminal ends of the A3 domain are in close vicinity via a disulfide bridge between Cys1686 and Cys1872.

Structure of the A3 domain/collagen complex. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF A3 domain in complex with a collagen III triple-helical peptide derived from PDB-deposit 4DMU.69 Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Three-dimensional representation of nanobody KB-VWF-D3.1 docked onto the A3 domain.70 The nanobody’s binding site overlaps the interactive surface involved in collagen binding. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the A3 domain. Circles indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with reduced collagen binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2M. Note, in the 3-dimensional space, the N- and C-terminal ends of the A3 domain are in close vicinity via a disulfide bridge between Cys1686 and Cys1872.

Unexpectedly, only 2 patient mutations have been identified that are directly within the interactive surface: Val1760Ile and Arg1779Leu; although it has not specifically been reported whether these mutations indeed affect collagen binding. Patient mutations that have been described to modulate collagen binding are actually outside this surface (Leu1696Arg, Ser1731Thr, Trp1745Lys, Ser1783Ala, His1786Asp, and Pro1824His; Figure 5C).71-75 The underlying mechanism by which they impair collagen binding is yet unclear but may be related to an indirect disturbance of the collagen-binding surface.

Binding to collagen resembles that to GpIbα in that larger multimers are more efficient in collagen binding than smaller multimers.76 In contrast, collagen binding differs from GpIbα binding because it may occur already under static conditions, indicating that the A3 domain does not require shear-induced conformational changes to expose its collagen-binding site. Does this mean that the A3 domain is rather static in terms of conformation? Probably not, and there are 2 indications that point in this direction. First, after the association of VWF to collagen, the affinity of VWF for FVIII is reduced, resulting in the release of FVIII.77 Thus, collagen binding via the A3 domain causes structural changes toward the D’D3 region. Second, we recently identified a nanobody (KB-VWF-D3.1), whose binding sites overlaps the collagen-binding site (Figure 5B).70 Its binding was strictly dependent on the A2 domain being intact, and ADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis was associated with a loss of binding. One potential explanation is that cleavage in the A2 domain induces changes in the adjacent A3 domain, notably the collagen-binding site. As such, ADAMTS13 not only modulates collagen binding by reducing multimer size but also by indirectly modifying the exposure of the collagen-binding site.

αIIbβ3 binding to the C4 domain

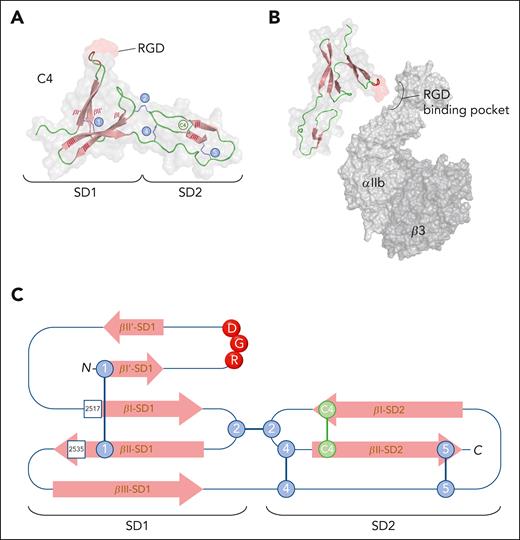

The C-terminal portion of the mature VWF subunit contains 6 consecutive von Willebrand C (VWC) domains, also known as chordin-like cysteine-rich domains. Each domain is relatively small compared with the A and D domains, containing 68 to 80 residues.5 The general VWC-fold comprises 2 subdomains (SDs; SD1 and SD2) that are linked by a disulfide bridge.78 SD1 contains 5 antiparallel β-strands and the SD2 domain contains 2 antiparallel β-strands, and internal disulfide bridges between β-strands help to stabilize the overall fold of the VWC module. Indeed, each VWC domain contains a CxxCxC motif and a CCxxC motif, which mediate the formation of these disulfide bridges.5,79

Although structures of homologous VWC domains were previously solved,80-82 it took until 2019 before the first structure of a VWF C domain was reported, that is the C4 domain (residues Ser2497-Glu2577).83 The relevance of solving the structure of the C4 domain is that it contains an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif that mediates binding of VWF to integrins αIIbβ3 and αVβ3.84-87

As expected, the C4 domain displays a typical VWC-fold characterized by several antiparallel β-strands in SD1 and SD2 (Figure 6A-B). However, the distribution of the disulfide bridges differs from other instances of the fold. Collagen IIA, cellular communication network factor 3, and Crossveinless-2 all share 5 disulfides.83 Four of these are also found in the VWF C4 domain (Figure 6A). However, a conserved disulfide connecting β-strands βII and βIII in SD1 of other proteins is not found in the VWF C4 domain, which instead contains a unique disulfide linking strands βI and βII in SD2 (Figure 6A).

Structure of the C4 domain. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF C4 domain derived from PDB-deposit 6FWN.83 The RGD motif is highlighted in red. SD1 and SD2 represent subdomains 1 and 2, respectively. Conserved disulfide bridges (1, 2, 3, and 5) are indicated in blue, and the C4-specific disulfide bridge (C4) is in green. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Provisional alignment (not at scale) of the RGD motif within the C4 domain (PDB-deposit 6FWN) with the RGD-binding pocket of αIIbβ3 (PDB-deposit 3ZDX). Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the C4 domain. SD1 and SD2 refer to subdomains 1 and 2, respectively. Blue circles indicate disulfide bridges conserved among VWC domains, whereas green circles represent the disulfide bridge that is unique to the C4 domain. RGD motif is indicated with red circles. Squares indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with reduced αIIbβ3 binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2M.

Structure of the C4 domain. (A) Three-dimensional representation of the VWF C4 domain derived from PDB-deposit 6FWN.83 The RGD motif is highlighted in red. SD1 and SD2 represent subdomains 1 and 2, respectively. Conserved disulfide bridges (1, 2, 3, and 5) are indicated in blue, and the C4-specific disulfide bridge (C4) is in green. Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (B) Provisional alignment (not at scale) of the RGD motif within the C4 domain (PDB-deposit 6FWN) with the RGD-binding pocket of αIIbβ3 (PDB-deposit 3ZDX). Figure was generated using PyMOL software. (C) Two-dimensional representation of the C4 domain. SD1 and SD2 refer to subdomains 1 and 2, respectively. Blue circles indicate disulfide bridges conserved among VWC domains, whereas green circles represent the disulfide bridge that is unique to the C4 domain. RGD motif is indicated with red circles. Squares indicate positions of residues where mutations have been associated with reduced αIIbβ3 binding in patients with von Willebrand disease-type 2M.

A second unique feature is the presence of the RGD motif in the VWF C4 domain, which is located in the N-terminal portion of the SD1 domain, between the βI’ and βII’ strands. In the majority of VWC domains, these β-strands are separated by a very short 2-amino acid loop, whereas in the VWF C4 domain, this sequence consists of a 10-amino acid hairpin structure, allowing outward exposure of the RGD motif (Figure 6A-B).83

The continuous exposure of the RGD site is compatible with the notion that VWF can bind αIIbβ3 under static conditions. In terms of visualization, there is currently no high-resolution cocomplex of the C4 domain with αIIbβ3 reported. However, Zhou et al generated low-resolution electron microscopy images of the VWF D4-CK fragment in complex with αIIbβ3.5 In these images, αIIbβ3 is perpendicularly bound to the C4 domain, further confirming that the RGD motif is well exposed. Nevertheless, the exposure of the RGD is somehow conformation dependent, illustrated by the finding that mutations within neighboring C domains have been associated with reduced VWF binding to αIIbβ3.88 It seems probable that these mutations perturb the conformation of the RGD-interactive surface.

As for the C4 domain itself, mutations within this domain affecting αIIbβ3 binding are rare, and to the best of our knowledge, only 2 have been reported: Val2517Phe and Arg2535Pro (Figure 6C).89 These mutations are associated with a mild bleeding tendency and may be classified as VWD-type 2M. In line with this mild bleeding tendency are the observations that blocking the RGD motif using a monoclonal antibody or via mutagenesis results in a mild bleeding tendency in mice.90,91 Interestingly, detailed analysis of real-time thrombus formation in these mice revealed an increased instability of the thrombus.90 This suggests that the VWF/αIIbβ3 interaction contributes to the stabilization of platelet-platelet interactions, akin to the role of fibrinogen.

In terms of multimerization, it seems that binding of VWF to αIIbβ3 is multimer-size independent. By comparing plasmas from 85 healthy participants and 115 patients with different types of VWD, including type 2A and type 2B, no differences in αIIbβ3 binding were detected.92

Response to shear stress

Conformational changes due to physical forces are key to the control of VWF function. Coiled VWF multimers unfold into an elongated conformation, the extension of which increases with higher shear.93,94 However, extension in itself is insufficient to allow for binding. For instance, Fu et al observed elongation of VWF at shears between 80 and 480 dyn/cm2, whereas GpIbα binding required minimal 720 dyn/cm2.93 Apparently, the force needed to break internal interactions between VWF monomers within a single multimer (estimated to be <0.1 pN at 80 dyn/cm2) is lower than the force that is required to unlock the AIM structure to induce the high-affinity GpIbα-binding conformation (estimated to be 21 pN).93 The forces required for GpIbα binding are also higher than the forces needed to unfold the A2 domain, which have been determined to be ∼1 pN.8 Regarding the other ligands (FVIII, collagen, and αIIbβ3), it seems that shear contributes little to their interaction, because these ligands bind already efficiently under static conditions.

Interestingly, shear does not only contribute to some of the VWF-ligand interactions but also directs intermolecular self-association, a means to generate longer and thicker VWF fibers. VWF self-association was first reported by Savage et al, who observed that circulating VWF could associate with surface-bound VWF under high shear.95 More recently, it was shown that this process is reversible, self-limiting, and requires a minimal shear of 240 to 480 dyn/cm2, lower than what is needed for GpIbα binding.96 Apart from shear, other mechanisms also regulate self-association. First, ADAMTS13 will limit self-association via proteolysis of extended VWF multimers.97 Second, lipoproteins change the extent to which VWF multimers can self-associate: low-density lipoproteins enhance self-association, whereas high-density lipoproteins have the opposite effect.97,98 Finally, VWF mutations Arg1597Trp (VWD-type 2A) and Val1316Met (VWD-type 2B) are associated with increased self-association.99,100

Conclusion

The generation of high-resolution 3-dimensional structures have identified VWF-specific configurations that distinguishes its domains from homologous domain structures in other proteins. These structural adaptations provide VWF with the ability to regulate its interactions with a spectrum of ligands at the submolecular level to bind each ligand at the right time. This tight regulation also makes the VWF protein vulnerable in that it can be perturbed by a wide range of mutations. Indeed, VWD-related mutations are not restricted to a particular hot spot but are dispersed over the whole protein. With the support of novel structural insights, we better understand how each group of mutations may impair VWF function.

So far, the structural studies that we have highlighted in this review have focused on the classic ligands for VWF. However, VWF interacts with a large number of other ligands, including circulating proteins as well as cellular receptors.2,3 Currently, we know little about where these ligands exactly bind to VWF and how their binding is regulated. Combining functional studies with the generation of additional 3-dimensional structures may help us to better visualize this particular aspect. This is of relevance in view of the notion that there is convincing evidence that VWF functions extend beyond hemostasis, and it is important to appreciate how these functions are regulated at the molecular level.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Caterina Casari for her contribution to the design and editing of the manuscript and Ivan Peyron for preparation of the figures.

Authorship

Contribution: P.J.L., C.V.D., and O.D.C. designed and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.J.L., C.V.D., and O.D.C. are inventors on patents related to von Willebrand factor. P.J.L. currently receives research funding (to the institution) from BioMarin, Sobi, and Sanofi.

Correspondence: Peter J. Lenting, INSERM U1176, 80 rue du Général Leclerc, 94276 Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France; email: peter.lenting@inserm.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal