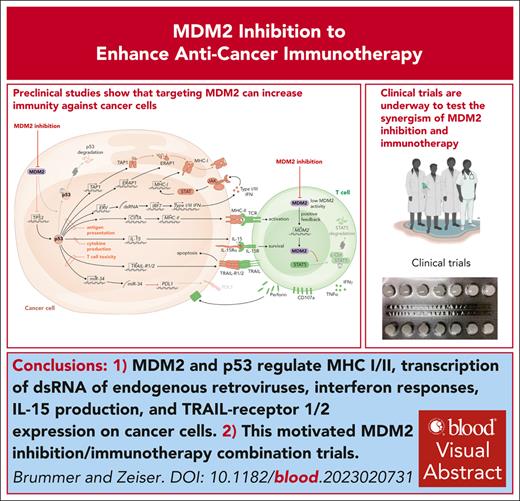

Visual Abstract

Mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) is a negative regulator of the tumor suppressor p53 and is often highly expressed in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and other solid tumors. Inactivating mutations in TP53, the gene encoding p53, confers an unfavorable prognosis in AML and increases the risk for relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. We review the concept that manipulation of MDM2 and p53 could enhance immunogenicity of AML and solid tumor cells. Additionally, we discuss the mechanisms by which MDM2 and p53 regulate the expression of major histocompatibility complex class I and II, transcription of double stranded RNA of endogenous retroviruses, responses of interferons, production of interleukin-15, and expression of tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis–inducing ligand receptor 1 and 2 on malignant cells. The direct effects of MDM2 inhibition or MDM2 deletion in effector T cells are discussed in the context of cancer immunotherapy. The preclinical findings are connected to clinical studies using MDM2 inhibition to enhance antitumor immunity in patients. This review summarizes current evidence supporting the use of MDM2 inhibition to restore p53 as well as the direct effects of MDM2 inhibition on T cells as an emerging concept for combined antitumor immunotherapy against hematological malignancies and beyond.

Introduction

The mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) protein functions both as a ubiquitin ligase that recognizes the N-terminal transactivation domain of p53, leading to its degradation and as an inhibitor of p53 transcriptional activation.1 The MDM2 effects are mediated by reducing p53 abundance and function, with a consequent failure to arrest the cell cycle when DNA damage occurs in tumor cells. MDM2 amplification and overexpression reportedly cause resistance to therapy in different tumor entities.2 MDM2 inhibitors can induce p53 reactivation and consecutive apoptosis in different cancer cell types.1,3,4 Apart from these effects on cell cycle regulation and apoptosis, a role of the MDM2/p53 axis in regulating immune-related genes has been recognized. p53 is essential for interferon (IFN)-mediated antiviral immunity,5 and MDM2 inhibition increases major histocompatibility complex class I and II (MHC I and II) expression on acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells in a p53-dependent manner.6 Reduced MHC expression allows cancer cells to evade recognition by T cells. Genetic TP53 abnormalities are reportedly associated with immune infiltration and response to immunotherapy in AML.7

The observation that MDM2 antagonists induce p53-dependent apoptosis in AML3 motivated clinical studies in this disease entity. However, the phase 3 MIRROS trial, which tested the MDM2 antagonist idasanutlin in relapsed or refractory AML, revealed that the primary end point, improved overall survival, was not met (median, 8.3 vs 9.1 months with idasanutlin + cytarabine vs placebo + cytarabine [NCT02545283]).8 This result suggests that using MDM2 inhibition for AML outside of an immunotherapy setting may not be sufficient and that a combination with immunotherapy, such as allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) or immune checkpoint inhibitors, may be required for its activity. MDM2 was shown to play a central role in antitumor immune responses against solid tumors9,10 and hematological malignancies6 in preclinical models. Multiple trials are ongoing that evaluate the safety and efficacy of MDM2 inhibition in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitor–based and allo-HCT–based immunotherapies.

A better understanding of how to enhance the proinflammatory function of p53 by MDM2 manipulation may improve cancer immunotherapy and, ultimately, the outcomes of our patients.

Normal function of p53

The p53 protein was originally discovered in the late 1970s as an interaction partner of the large T antigen of the polyomavirus simian virus 40 (reviewed previously11). The T antigen disables the retinoblastoma and p53 tumor suppressor pathways and, thereby, counteracts cellular senescence and contributes to malignant transformation by promoting proliferation under nonoptimal environmental circumstances and in the context of unrepaired or incompletely replicated genomes.12 When p53 was discovered, it was originally described as an oncoprotein. Moreover, TP53, encoding human p53, represents the most frequently mutated gene in human cancer11 and many of its mutations affect only 1 allele, thereby resembling typical dominant acting oncogenes such as RAS. Other groups, however, have described it as a tumor suppressor gene (TSG), because its biallelic loss promotes tumorigenesis. This TSG function was further supported by in vivo experiments and the association of TP53 mutations with Li Fraumeni syndrome, both highlighting the typical recessive character of TSGs. This conundrum was resolved when the tetrameric nature of the p53 protein was discovered, which immediately proposed a mechanism for the dominant-negative mode of action of TP53 mutations because of the fact that a single mutant monomer impedes the function of the entire tetramer.13 Subsequent research identified p53 as a transcriptional regulator controlling a plethora of cellular responses after a diverse set of insults, such as irradiation or replicative stress, including that caused by proproliferative oncogenes. A major and the most portrayed function of p53 as the guardian of the genome14 is its ability to induce cell cycle arrest by upregulating cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21, which in turn causes cell cycle arrest until a sustained DNA damage has been repaired via processes that are, in part, also orchestrated by p53.11 However, if the sustained damage is too severe, p53 will trigger programmed cell death instead. This altruistic program ensures that cells with unrepaired mutations, for example, within oncogenes, are eliminated before they can give rise to tumor cells. More recent data show that p53 can also mediate (oncogene-induced) senescence, which represents another barrier against tumorigenesis. These models are not only strongly supported by the coexistence of TP53 mutations along with alterations in potent oncogenes, such as KRAS in human cancers, but also by data from mouse models, in which Trp53 point mutations or deficiency accelerate the onset and progression of KrasG12D-driven tumors.15 In addition to these textbook examples of p53 function, multiple other physiological roles for this protein have emerged, such as the control of metabolic processes (eg, glutamine catabolism), control of translation, or the induction of autophagy.11 The p53 protein also controls the expression of its own regulator, Mdm2 (also known as Hdm2 in the human context), by binding to its promotor. For example, this negative feedback loop ensures that after a surge in p53 expression as part of a cell cycle–arresting stress response, cells resume proliferation because the increasing levels of de novo–expressed Mdm2 trigger the proteasomal degradation of p53, which in turn results in decreased p21 expression.16

The mind-boggling diversity of p53 functions can be explained by the fact that this transcription factor directly controls >100 target genes, whose products might affect thousands of other gene products.17,18 This plethora of (in)direct p53 targets raises the question of how p53-mediated processes, which are increasingly recognized as plastic, dynamic, and graded rather than “on-off”–like,11 are fine tuned as adequate responses to environmental stimuli. Consequently, the elucidation of the mechanisms guiding p53 to stimuli-specific loci to achieve the most appropriate response to the type of stress endured represents an intense area of research. It is anticipated that the target gene spectrum of p53 is dynamically modulated by a complex layer of context-specific protein–protein interactions and posttranslational modifications.17

Research over the last 4 decades identified a large spectrum of TP53 alterations, including point mutations modifying the sequence of the p53 protein, particularly within the DNA binding domain, and truncations due to premature stop codons and frame-shifts. Interestingly, the analysis of thousands of tumor genomes revealed that the frequency and localization of alterations within TP53 can considerably vary between tumor entities.11 Importantly, from the view point of tumor genome sequencing for clinical purposes, all these mutations do not behave in the same way, because some can be classified as typical loss-of-function mutations, whereas others diminish or extend the portfolio of wild-type p53. The latter are often regarded as neomorphic alterations, in which novel functions appear due to mutational effects on the stability folding or of the protein and, thereby, might influence promotor selectivity and tumor aggressiveness and responsiveness.11 Lastly, the genomes of DNA tumor viruses encode oncoproteins that disable p53 function in the absence of TP53 alterations.19 Prominent examples are the aforementioned T antigens of polyoma viruses and the E6 protein of high-risk human papillomavirus strains, which cause p53 deficiency at the protein level by promoting p53 destruction.20 Based on the mechanisms that we discuss hereafter, it is tempting to speculate that these processes not only contribute to the initiation of tumorigenesis but also allow DNA tumor viruses to hide from the immune system in their host cells via the p53 axis.

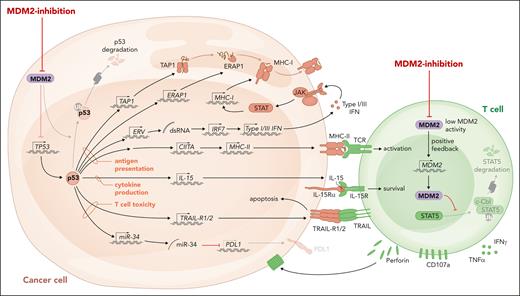

The MDM2/p53 axis and antigen presentation

MHC peptide complexes activate T cells with a suitable T-cell antigen receptor. Although MHC I molecules mainly present peptides derived from intracellular proteins, MHC II molecules present extracellular proteins that were taken up or are derived from intracellular pathogens. AML cells exhibit downregulation of MHC I and II compared with healthy myeloid cells, thereby reducing their immunogenicity (previously reviewed21). Downregulation of MHC molecules is reportedly a mechanism of leukemia immune evasion after allo-HCT, which is associated with relapse in patients.22,23 MHC expression on leukemia cells is controlled by epigenetic mechanisms24 and the transcriptional activator of MHC II called CIITA.25 Expression of CIITA and MDM2 were negatively correlated in 2 different AML cohorts,6 supporting the concept that negative regulation of p53 by high MDM2 expression and low MHC expression are functionally connected. AML cells lacking p53 were resistant to the upregulation of MHC II upon MDM2 inhibition.6 The connection between p53 and MHC molecule expression is not restricted to hematological malignancies because MDM2 inhibition in healthy dendritic cells increased MHC II expression.26 Besides MHC I and II expression, the antigen presentation machinery requires functional antigen peptide transporter 1 and the endoplasmic reticulum. The antigen peptide transporter 1 was shown to rely on intact p53 for the transport and the expression of surface MHC peptide complexes (Figure 1), whereas this function was impaired in the presence of p53 loss-of-function mutations.27 Another component of the antigen presentation machinery is endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1), which cuts N-terminal–extended peptides to the necessary length for assembling with MHC I.28 p53 was shown to increase MHC I expression by upregulating ERAP1.29 The cognate response element of the ERAP1 gene cannot recruit mutant p53, which explains why the expression of MHC I was reduced in human colon carcinoma cell lines carrying p53 mutations.28 In agreement with this finding, MHC I expression could be increased by MDM2 inhibition, when murine or human melanoma cells were exposed to MDM2 inhibition.10 The observation could be extended to MHC II, and it was shown that intact p53 is required for this effect.10 In melanoma-bearing mice, MDM2 inhibition enhanced the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy.10 Additionally it was shown that pharmacological activation of p53 by MDM2 inhibition caused the expression of genes encoding endogenous retroviruses (ERVs).30 The derepression of the ERV-triggered ERV–double stranded RNA–IFN pathway was shown to cause the transcription of genes related to antigen processing and presentation, including β2-microglobulin, HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C.30 The proposed mechanisms of action of MDM2 inhibition in cancer cells and T cells are summarized in Figure 1. Additionally, the MDM2 inhibition and p53 activation effect leads to cancer cell cytolysis, and the effect on immune activation may be also a secondary effect because dying cancer cells can elicit an immune response. Further studies are warranted to address whether MDM2 inhibition in immune cells supports the antitumor immune response as a general concept.

The proposed role of MDM2/p53 in antitumor immunity. MDM2 inhibition and the consecutive increase in p53 lead to enhanced MHC I and II expression, activation of ERV with consecutive double stranded RNA release and type 1 and 3 IFN responses, IL-15 production, and TRAIL-R1/2 transcription in malignant cells. The direct effects of MDM2 inhibition or MDM2 deletion in effector T cells include increased production of perforin and other cytotoxic molecules.

The proposed role of MDM2/p53 in antitumor immunity. MDM2 inhibition and the consecutive increase in p53 lead to enhanced MHC I and II expression, activation of ERV with consecutive double stranded RNA release and type 1 and 3 IFN responses, IL-15 production, and TRAIL-R1/2 transcription in malignant cells. The direct effects of MDM2 inhibition or MDM2 deletion in effector T cells include increased production of perforin and other cytotoxic molecules.

MDM2/p53 and T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity

MDM2 inhibition and consecutive p53 increase caused the upregulation of tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis–inducing ligand receptor 1 and 2 (TRAIL-R1/2) on AML cells.6 This observation opens a therapeutic window to increase the susceptibility of AML cells to T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity via their expression of TRAIL. In agreement with a role of TRAIL induced by MDM2 inhibition, previous studies had shown that the TRAIL/TRAIL-R axis plays a central role in the graft-versus-leukemia effect.31 TRAIL-R1/2 knockout rendered AML cells resistant to MDM2 inhibition and/or T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity.6 Although these effects occurred in the AML cells, MDM2 inhibition also had a direct effect on T cells, with an increased expression of cytolytic molecules, including perforin and CD107a, in CD8 T cells in naive mice treated with MDM2 inhibitor compared with in that in mice treated with the vehicle.6 A negative regulator of T-cell activation is programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1). The expression of its ligand, programmed death receptor-ligand 1 (PDL1), was shown to be downregulated by miR-34.32 The authors also described a negative correlation between p53 and PDL1 (CD274) messenger RNA expression in samples from 181 patients with non–small cell lung cancer.32 This suggests that restoring p53 expression via MDM2 inhibition may counteract the high PD-L1 expression observed in different cancer entities,33 which often relies on oncogene activation.34 In mouse tumor models, the MDM2 inhibitor CGM097 induced an increase in the number of dendritic cells, percentage of T cells in tumors and tumor-draining lymph nodes, and ratio of CD8+ T cells to regulatory T cells in tumors.35 In murine models, the MDM2 inhibitors BI-907828 and APG-115 were shown to induce synergistic activity with anti–PD-1 antibody–based immunotherapy.9 Myeloid cells located in the tumor microenvironment (TME) can act as potent positive regulators of T-cell function. Proinflammatory signaling, including cGAS-STING-TBK1-IRF3, in myeloid cells located in the TME is essential to generate antitumor T-cell responses. Recently, it was shown that p53 carrying loss-of-function mutations suppresses innate immune signaling, which enhance tumor growth.36 Mutant p53 was shown to impair the cytoplasmic DNA sensing machinery, which includes cGAS-STING-TBK1-IRF3.36 Mechanistically, the authors could show that mutant p53 engages TANK-binding protein kinase 1 (TBK1) and prevents the formation of a trimeric complex between TBK1, STING, and IRF3.36 This complex was shown to be essential for the transcriptional activity of IRF3 in the TME.36 Using in vitro T-cell–stimulation cocultures, it was shown that nutlin-3, an inhibitor of the MDM2/p53 interaction, increased the expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules on dendritic cells, which, in turn, increased he proliferation and activation of the stimulated T cells.26 Using p53-null orthotopic models of murine hepatocellular carcinoma, the authors observed that p53 messenger RNA nanoparticles combined with anti–PD-1 immunotherapy caused an increase in the fraction of IFN-γ+ tumor necrosis factor α–positive CD8+ T cells in the TME of murine hepatocellular carcinoma.37 These observations, showing that restoration of functional p53 leads to tumor regression and immune activation in mice, indicate that the p53 function in the TME may rely on immune-mediated mechanisms, which are beyond the classical functions, including cell cycle regulation and apoptosis induction.

MDM2/p53 and cytokine production

The impact of MDM2 inhibition depends on the cell type; for T cells it was shown that MDM2 inhibition can induce production of tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ,6 whereas in melanoma cells MDM2 inhibition induces interleukin-15 (IL-15) production.10 IL-15 serves as an activator of antitumor CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells, and a recent clinical trial including patients with metastatic malignancies showed increased numbers of natural killer cells and CD8+ memory T cells upon IL-15 treatment.38 IL-15 production induced by FLT3 inhibition in FMS-like tyrpsine kinase-3 interal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) mutant leukemia cells led to increased antitumor immune responses in mice undergoing allo-HCT.39 Melanoma cells may downregulate cytokine production and MHC expression in neighboring immune cells to escape immune responses using microRNAs.40 Recently, it was shown that MDM2 inhibition can induce IL-15 production in human and murine melanoma cells.10 Furthermore, another group reported that MDM2 inhibition enhanced antitumor immune responses by altering cytokine production in the TME in a p53-dependent manner.35 MDM2 inhibition leads to increased MDM2 production via a positive feedback loop. The increased MDM2 levels in immune cells may have beneficial effects on anticancer immune responses, because it was reported that MDM2 stabilizes signal transducer and activator of transcription 5, thereby leading to enhanced T-cell–mediated antitumor immunity.41 MDM2 deletion was shown to reduce IFN responses in T cells, thereby decreasing antitumor immune responses.41 Conversely, the lack of MDM2 in T cells reduced antitumor immunity.41 In agreement with a transcriptional activation of IFN genes, the IFN regulatory factor 5 gene was shown to be a direct target of p53.42

Clinical trials testing MDM2 inhibition in combination with immunotherapy

Multiple ongoing clinical trials assess the efficacy of MDM2 inhibition in combination with immunotherapy (Table 1). The MDM2 inhibitor siremadlin is tested in a phase 1b/2, single arm, open-label, multicenter study as a monotherapy and in combination with donor lymphocyte infusions in patients with high-risk AML after allo-HCT, based on the presence of pretransplant risk factors (NCT05447663). The study is designed to identify the safe dose and schedule of siremadlin in the context of allo-HCT and assess the preliminary efficacy in preventing AML relapse (NCT05447663). Additionally, siremadlin is being tested in patients with AML or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), outside of the allo-HCT context, in a phase 1b, multiarm, open-label study in combination with an anti-TIM3 antibody (MBG453) or venetoclax (NCT03940352).

MDM2 inhibition is also being studied in combination with immunotherapy in different solid tumors.43 In a phase 1 dose-escalation study that tested the combination of the MDM2 inhibitor APG-115 and pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic solid tumors (NCT03611868), no dose-limiting toxicities were observed, and a fraction of patients experienced responses.43 The analysis of tumor tissue derived from patients exposed to the MDM2 inhibitor CGM097 showed that tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells were increased.35 For patients with different cancer entities, including colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and renal cell cancer, the anti−PD-1 antibody spartalizumab is being tested in combination with siremadlin (NCT04785196). The combination of pembrolizumab and MDM2 inhibition using the MDM2 inhibitor APG-115 is being tested in a phase 1b /2 trial in patients with advanced solid tumors. These trials indicate the great interest in overcoming immune resistance via MDM2 inhibition. A concern when combining immunotherapy with MDM2 inhibition is cumulative toxicity due to immune-related adverse events, such as treatment-refractory colitis44 and hepatitis, and MDM2 inhibitor–related adverse effects, such as cytopenias and gastrointestinal intolerance, which have been described in multiple clinical trials (Table 2). Different mechanisms of action of reported MDM2 inhibitors or p53 stabilizers are summarized in Table 3.

Cancers that inactivate the p53 tumor suppressor, through mutation or deletion, are more aggressive and show increased resistance to many therapies. Inactivation of p53 frequently occurs in secondary therapy–related MDS and AML. Different strategies to overcome p53 inactivation have been tested. For example, restoration of transcriptional p53 activity with eprenetapopt (APR-246) in combination with azacitidine for patients with p53-mutated MDS/AML has induced an overall response rate of 71%, with 44% of patients achieving complete remission.62 Furthermore, PC14586, a selective small molecule p53 reactivator against the TP53 Y220C mutation (NCT04585750), is being tested in clinical trials as a monotherapy or in combination with pembrolizumab. Sulanemadlin (ALRN-6924) is an inhibitor of the p53-MDM2, p53-MDMX protein–protein interactions. These effects are likely independent of immune activation.

COTI-2 is a third-generation thiosemicarbazone drug that transforms the mutant conformation of p53 to a form with specific wild-type abilities63 and, thereby, returns to normal wild-type p53 target gene expression.64 COTI-2 as a monotherapy or in combination with standard therapies has already undergone evaluation for the treatment of several different types of recurrent cancers in a phase 1 clinical trial (NCT02433626). Additionally, arsenic trioxide is effective against p53 mutant AML. Moreover, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) act independently of p53 mutations. MDM2-directed PROTACs selectively bind to the p53 site on the surface of MDM2, stabilizing p53 and degrading target protein (previously reviewed65). An example of a PROTAC MDM2 degrader is MD-224, which targets MDM2 protein for degradation.66

Conclusions and outlook

Despite improvements in the outcomes of patients with different malignancies because of novel immunotherapies, immune escape is still a major hurdle, leading to primary and secondary therapy resistance. The discussed reports showing that the MDM2/p53 axis is a central regulator of immune escape via effects on antigen presentation, cytokine production, T-cell activation, and T-cell–mediated apoptosis susceptibility indicate that pharmacological intervention to restore p53 expression could help to enhance anticancer immunotherapy. Based on these studies in preclinical models and patient cohorts, multiple clinical studies that combine MDM2 inhibition and immunotherapy are ongoing.

A critical point may be that many cancer entities carry high frequencies of inactivating p53 mutations that cannot be corrected by MDM2 inhibition. However, there is evidence for a direct activating effect of MDM2 inhibition on T cells independent of the TP53 mutational status of the cancer cell.6 Moreover, PC14586, eprenetapopt (APR-246), and COTI-2, which induce p53 activity also in the presence of p53 mutations, could be used and tested for synergism with immunotherapy. Future clinical studies need to clarify whether combining MDM2 inhibition with immunotherapies, such as allo-HCT, chimeric antigen receptor T cells, bispecific antibodies, or immune checkpoint inhibitors, increases response rates over immunotherapy as monotherapy.

Acknowledgments

T.B. and R.Z. were supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation), Sonderforschungsbereich (SFB)-1479, project ID: 441891347; SFB TRR167 and European Research Council (ERC) advanced grant (ERC-2022-ADG, proposal no. 101094168 AlloCure) (R.Z.) by the Germany’s Excellence Strategy (Centre for Integrative Biological Signaling Studies, EXC-2189, project ID 390939984) (R.Z.).

Authorship

Contribution: R.Z. and T.B. wrote the first version of the manuscript, performed the literature review, included corrections of the revised version, and approved the final version for submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.Z. has received honoraria from Novartis, Incyte, Sanofi, Mallinckrodt, and VectivBio. T.B. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert Zeiser, Department of Medicine I (Hematology, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation), Faculty of Medicine, Medical Center, University of Freiburg, Hugstetter Str 55, D-79106 Freiburg, Germany; email: robert.zeiser@uniklinik-freiburg.de.