Abstract

The number of patients with primary cutaneous lymphoma (PCL) relative to other non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) is small and the number of subtypes large. Although clinical trial guidelines have been published for mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome, the most common type of PCL, none exist for the other PCLs. In addition, staging of the PCLs has been evolving based on new data on potential prognostic factors, diagnosis, and assessment methods of both skin and extracutaneous disease and a desire to align the latter with the Lugano guidelines for all NHLs. The International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL), the United States Cutaneous LymphomaConsortium (USCLC), and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) now propose updated staging and guidelines for the study design, assessment, endpoints, and response criteria in clinical trials for all the PCLs in alignment with that of the Lugano guidelines. These recommendations provide standardized methodology that should facilitate planning and regulatory approval of new treatments for these lymphomas worldwide, encourage cooperative investigator-initiated trials, and help to assess the comparative efficacy of therapeutic agents tested across sites and studies.

Introduction

The term primary cutaneous lymphoma (PCL) refers to a heterogeneous group of T-cell and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) that present in the skin (Table 1).1,2 The first revision to the 1979 original TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging of the most common type of PCL, mycosis fungoides (MF) and its leukemic counterpart, Sézary syndrome (SS), was published in 2007.3 Subsequently, suggested modifications to the blood classification of the now TNMB (blood) staging and recommendations for clinical trial design for MF/SS were published in 2011.4 In the current paper, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL), the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium (USCLC), and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) (the Tri-Societies) address the use of clonality in the staging of skin and extracutaneous sites, the preferred method for determining blood classification, and the addition of bone marrow (BM) involvement (and its definition) to visceral staging of MF/SS. We also have used the Lugano classification of NHLs5 for the first time in the diagnosis, assessment, and response criteria for extracutaneous disease and have addressed the utilization of core biopsy vs excisional biopsy in determining lymphomatous involvement in MF/SS.

In 2007, recommendations for the staging of the non-MF/non-SS cutaneous lymphomas, which include both T- and B-cell cutaneous lymphomas, were published for the first time.6 However, there has been a lack of guidance on clinical trials for these conditions, forcing sponsors of such studies to try to use methods best fitted to MF/SS.

In this report, we present modifications to the tools used to document skin and lymph node staging (Table 2) and clarification of minor issues in the definition of the T stages for these non-MF/non-SS PCLs. We also present the first recommendations for a unified approach to diagnosis, assessment, and response criteria for clinical trials of all PCLs that are aligned with the Lugano classification and that can be used for these lymphomas worldwide.

Initial evaluation

Pathologic confirmation of diagnosis

All patients in a clinical trial should have a confirmed diagnosis of a subtype of PCL that includes characteristic pathologic features from a representative skin biopsy and clinical findings consistent with that diagnosis. Although a current biopsy is preferred, a prior skin biopsy can be used for diagnostic purposes provided all of the following criteria are met: (1) the type of lesion biopsied is representative of the highest-grade current skin lesion(s), (2) clinical/pathological correlation confirms the subtype of PCL, and (3) it provides sufficient information for all inclusion/exclusion criteria and stratification purposes. Time from prior diagnostic biopsy is not a sole reason to repeat a biopsy for a clinical trial. Terms such as “suspicious of” or “suggestive of” on pathologic examination are not sufficient for a diagnostic biopsy without further supportive findings including immunophenotyping and/or molecular studies (eg, clonality, pathogenic genomic variants) but can be acceptable if the biopsy has been done to merely confirm the continued presence of the lymphoma in a patient with a prior diagnostic biopsy. Methods of establishing clonality12-14 (Table 3) are particularly important in establishing or supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) vs benign mimickers but only required if findings on light microscopy, immunophenotyping, and clinicopathologic correlation are not in themselves diagnostic. Additional recommendations regarding diagnostic biopsies for MF/SS are shown in Box 1.

Additional recommendations regarding diagnostic biopsies and trial design considerations for MF/SS

There are certain nuances of a diagnostic skin biopsy in MF that relate to lesion type:

- 1.

Diagnostic skin biopsy: A diagnostic skin biopsy is necessary for study entry, whether performed in the past or during study screening.

- a.

Both patch and plaque stage lesions, including hypopigmented MF, should meet the criteria for the early MF algorithm.16 Prior to skin biopsy, a 2-week washout time from treatment likely to affect pathological results (systemic or skin directed, including purposeful sunlight exposure) will enhance the ability to make a definitive diagnosis.

- b.

In cases of erythroderma where a skin biopsy is only “suggestive of” or “suspicious of” MF/SS, the additional findings of aberrant phenotype, dominant TCR clone in the skin, and blood or LN involvement, particularly if there is a positive clone that matches skin, provide supportive evidence for a diagnosis of MF/SS and help to eliminate other causes of erythroderma such as a pseudolymphomatous drug eruption.

- c.

Cases designated as Sézary syndrome for clinical trial purposes should meet pathologic and clinical criteria for erythrodermic MF/SS and have B2 blood involvement including clone in blood that matches skin.

- d.

Tumor lesions only “suggestive of” or “suspicious of” MF pathologically, especially those with CD30+ large cell transformation, should not be entered in clinical trials of MF/SS without other supportive features of MF including preceding or concurrent patches and plaques that help distinguish MF from other CTCLs. If a tumor lesion has a negative γ and β TCR clone, then additional molecular studies are needed to rule out a T-cell–rich B-cell, NK-cell, or other lymphoma subtype.

- e.

If lesions clinically suggestive of follicular involvement (such as follicle-based patches or plaques, follicular papules, and/or alopecia in hair-bearing body areas) have not been biopsied, and folliculotropism may affect response to therapy in a given clinical trial, a biopsy of such lesions should be considered to confirm a diagnosis of folliculotropic MF and to assess whether early or advanced features are present.17

- 2.

Trial design considerations

- a.

Patients in whom the abnormal lymphocytes on skin biopsy are predominantly CD8+, CD4−/CD8−, CD4+/CD8+, or other uncommon pathologic subtypes of MF/SS should either be excluded from a clinical trial of CD4+ MF/SS or separate reporting carried out from those with CD4+ MF/SS.

- b.

Adult T-cell leukemia lymphoma should be considered in all cases of potential MF/SS, especially those with CD4+/CD8+ phenotype, with strong expression of CD25, in locations where it is endemic, or with significant blood involvement.

- c.

Although trial design may allow inclusion of patients with MF variants, consideration should be given to tracking their responses separately to determine if their inclusion affects overall response. These variants include but are not limited to folliculotropic, syringotropic, and granulomatous MF (pathologically determined), hypopigmented MF, pagetoid reticulosis, and granulomatous slack skin.

- d.

In general, patients with large cell transformation, especially those of MF stage ≥IIB, have a proven worse prognosis.7,18 Determination of how their inclusion in clinical trials could affect overall trial results should be done prior to study onset.

Evaluation procedures at screening

Physical exam

This should include skin assessment (see below) and palpation of all peripheral nodal groups, liver, and spleen. A lymph node (LN) of >1.5 cm in the longest diameter (LDi) is considered abnormal, especially if accompanied by other features of concern (firm, rubbery, and/or fixed) but should be confirmed by imaging. A negative physical exam for abnormal nodes does not rule out the possibility of finding enlarged nodes on imaging studies, especially in obese individuals.15

Staging/classification

This will require imaging, potential biopsy of a suspect LN or visceral site, and in the case of MF/SS, specific blood studies. Although the current TNM(B) classification is generally used for study entry purposes, the original or highest TNM(B) classification may be used for inclusion/exclusion purposes or separation into prognostic or treatment groups depending on study goals.

ECOG performance status

See Oken et al.19

General blood tests

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential, metabolic panel, liver function tests, and serum lactate dehydrogenase.

Other blood tests

Screening for hepatitis B and C viruses, HIV, or other viruses should be trial-specific but considered where immunosuppression is likely from a given treatment or in early phase trials where all potential adverse effects of the study agent(s) are not known. With CTCL, testing for human T-lymphotropic virus types 1 and 2, if not previously done, should be considered.

Quality of life (QoL) assessment

Pruritus assessment

For those PCLs where pruritus is a significant issue, a visual analog scale or other validated tool is recommended to assess severity.

Study design

The purpose of the study, accrual expectations, the type and stage/classification of PCL, and the type of treatment will determine how long the duration of the trial should be. An active control is recommended for pivotal/approval studies where feasible and where appropriately validated standard of care exists for the subtype and stage of PCL. Although suboptimal, historical controls may be all that are currently available for comparison purposes with the less common subtypes of PCL.

A wash-out period is recommended for any treatment likely to affect the course of the lymphoma in order to minimize any latent clinical benefit or any residual toxicity from the prior treatment. The time period may be adjusted based on the biologic activity of the treatment, the aggressiveness of the lymphoma, whether the patient is experiencing progressive disease despite current treatment, or if study design warrants. A complete response (CR) should not be ascribed to a study drug while a patient is on concomitant therapy not otherwise part of study design with known efficacy for that PCL but rather the maximum response would be a partial response (PR). Those patients in whom a PR is achieved only while on such combination therapy should be noted in the final study report. Exceptions to concurrent therapy with proven efficacy in PCLs are topical or systemic steroids in those patients who have been on corticosteroids for prolonged time periods and where abrupt discontinuation prior to study start would lead to a potential flare of disease, adrenal suppression, and/or unnecessary suffering. In these latter patients, the use of ≤10 mg of prednisone or low potency topical steroids without an increase in dose or dosing frequency during the trial would not affect the assessment of response. Supportive care that may affect treatment results should be documented and remain constant throughout the study.

With statistical analysis, stratification by risk groups is likely to be of value in these PCLs as there are indolent and aggressive forms within each subtype of PCL. An intention-to-treat analysis is recommended for phase 3 clinical trials.

Assessment

Skin assessment

Skin assessment used for determination of response should be performed at baseline. Standardized photographs should be done at baseline and are encouraged at each skin assessment to aid in confirming response/progression. In a given study, only 1 assessment tool should be used for the purpose of determining response used as a primary endpoint. It is highly recommended that the same individual at a given site perform all skin assessments during a clinical trial, but because this may not be feasible, alternate personnel should have similar training on the method and, wherever possible, are present at baseline assessment of a given patient.

Patients with one of the clinical variants of PCL, such as hypo- or hyperpigmented MF or granulomatous slack skin, may require specific modes of assessment. Patients with non-MF/non-SS PCL who have primarily tumors may benefit from assessment methods that capture specific size of lesions. In these patients, size and location of lesions, and not percent body surface area (BSA), determine T classification. In patients in whom skin lesions primarily or exclusively present with induration without epidermal changes (such as subcutaneous panniculitis–like T-cell lymphoma), the periphery of the induration should be used as the margin of the lesions and the lesions characterized/weighted as tumors when using the skin assessment tool. If imaging with computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT), magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasound is used for initial study assessment, the same technique should be used to assess response.

These skin assessment guidelines are applicable to secondary, as well as primary, cutaneous lymphomas. Total body skin lesion assessment is necessary for trials in which global response is a consideration.

Skin assessment methods

Modified Severity Weighted Assessment Tool (mSWAT)

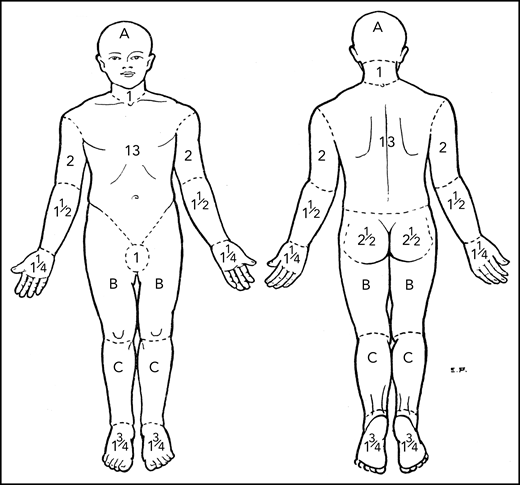

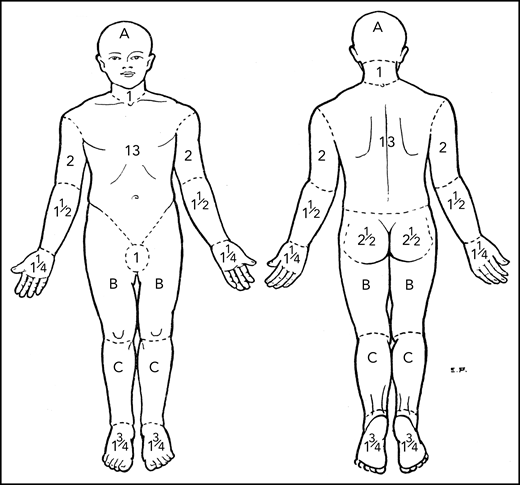

The mSWAT7,8 score has proven to be an effective means of assessment in multiple trials26-28 and accepted as valid by both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency. It has particular utility for MF/SS where multiple types of skin lesions are present in the same patient. The percent BSA involved with patch, papule/plaque, and tumor lesions (tumors defined as solid or nodular lesions with evidence of depth or vertical growth and ≥1 cm in diameter)7 are cataloged separately, multiplied by a relative weight of 1, 2, or 4 for patch, plaque, and tumor, respectively, and the sum of all 3 added for total score (Table 4). The percent BSA involved may be determined by using either the patient’s palm, representing 0.5% BSA, or the palm plus palmar surface of all 5 fingers, which is slightly less than 1% BSA.7,8,29 The regional BSA outlined by Lund and Browder30 (Figure 1; Table 4) provides a second method of assessing BSA for large areas involving similar kinds of lesions. The mSWAT has limitations, however, when it comes to assessment of BSA of tumors because individual tumors often cover <0.1% BSA. If the mSWAT is used to assess tumor lesions, it is important to score fractions of a percent of BSA and not round to the closest whole integer.

Regional areas of the body for assessment of total body skin lesions. Body region percent BSA for mSWAT determination by Lund and Browder.30 A, B, and C designate the body regions of head, thigh, and leg, respectively, for which they provided adjustments in BSA for children aged 1 to 5 years.

Regional areas of the body for assessment of total body skin lesions. Body region percent BSA for mSWAT determination by Lund and Browder.30 A, B, and C designate the body regions of head, thigh, and leg, respectively, for which they provided adjustments in BSA for children aged 1 to 5 years.

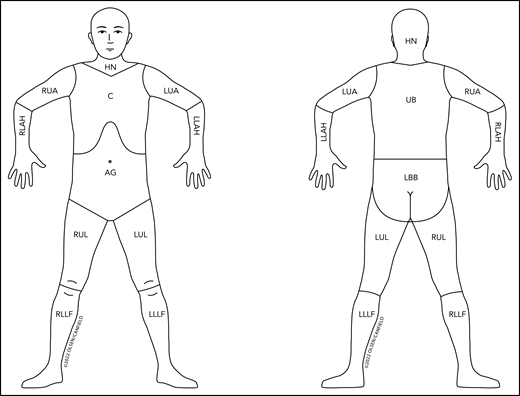

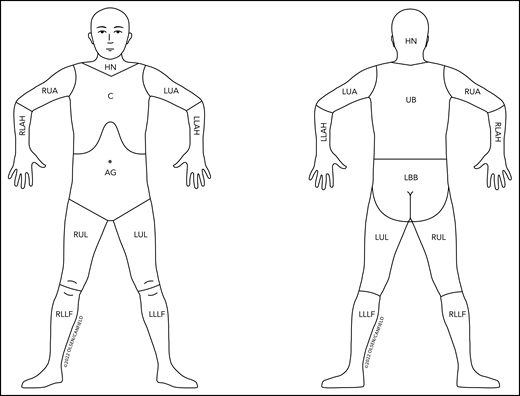

Figure 2 outlines the nodal regions draining skin as outlined by the Ann Arbor group31 and revises the regional lymph node drainage patterns in the prior published figure9 used in the staging of non-MF/non-SS CTCL and CBCL.

Revised nodal drainage areas for determination of classification of skin involvement in non-MF/non-SS PCLs. The nodal regions (based on the Ann Arbor classification)31 and their boundaries are as follows: head and neck (HN), inferior borders = clavicles anterior and T1 spinous process posterior; left upper arm (LUA), superior border = glenohumeral joint (exclusive of axilla), inferior border = ulnar/radial/humeral (elbow) joint; left lower arm and hand (LLAH), superior border = ulnar/radial/humeral (elbow) joint; right upper arm (RUA), superior border = glenohumeral joint (exclusive of axilla), inferior border = ulnar/radial/humeral (elbow) joint; right lower arm and hand (RLAH), superior border = ulnar/radial/humeral (elbow) joint; chest (C), superior border = superior border clavicles, inferior border = inferior margin rib cage, lateral borders = midaxillary lines and glenohumeral joints (inclusive of axilla); abdomen/genital (AG), superior border = inferior margin rib cage, inferior border = inguinal folds and anterior perineum; upper back (UB), superior border = T1 spinous process, inferior border = inferior margin rib cage, lateral borders = midaxillary lines; lower back/buttocks (LBB), superior border = inferior margin rib cage, inferior border = inferior gluteal fold and anterior perineum (inclusive of perineum), lateral borders = midaxillary lines; left upper leg (LUL), superior border = inguinal fold and gluteal folds, inferior border = midpatella anterior and mid–popliteal fossa posterior; left lower leg and foot (LLLF), superior border = midpatella anterior and mid–popliteal fossa posterior; right upper leg (RUL), superior border = inguinal fold and gluteal folds, inferior border = midpatella anterior and mid–popliteal fossa posterior; right lower leg and foot (RLLF), superior border = midpatella anterior and mid–popliteal fossa posterior.

Revised nodal drainage areas for determination of classification of skin involvement in non-MF/non-SS PCLs. The nodal regions (based on the Ann Arbor classification)31 and their boundaries are as follows: head and neck (HN), inferior borders = clavicles anterior and T1 spinous process posterior; left upper arm (LUA), superior border = glenohumeral joint (exclusive of axilla), inferior border = ulnar/radial/humeral (elbow) joint; left lower arm and hand (LLAH), superior border = ulnar/radial/humeral (elbow) joint; right upper arm (RUA), superior border = glenohumeral joint (exclusive of axilla), inferior border = ulnar/radial/humeral (elbow) joint; right lower arm and hand (RLAH), superior border = ulnar/radial/humeral (elbow) joint; chest (C), superior border = superior border clavicles, inferior border = inferior margin rib cage, lateral borders = midaxillary lines and glenohumeral joints (inclusive of axilla); abdomen/genital (AG), superior border = inferior margin rib cage, inferior border = inguinal folds and anterior perineum; upper back (UB), superior border = T1 spinous process, inferior border = inferior margin rib cage, lateral borders = midaxillary lines; lower back/buttocks (LBB), superior border = inferior margin rib cage, inferior border = inferior gluteal fold and anterior perineum (inclusive of perineum), lateral borders = midaxillary lines; left upper leg (LUL), superior border = inguinal fold and gluteal folds, inferior border = midpatella anterior and mid–popliteal fossa posterior; left lower leg and foot (LLLF), superior border = midpatella anterior and mid–popliteal fossa posterior; right upper leg (RUL), superior border = inguinal fold and gluteal folds, inferior border = midpatella anterior and mid–popliteal fossa posterior; right lower leg and foot (RLLF), superior border = midpatella anterior and mid–popliteal fossa posterior.

Skin Lesion Assessment Tool (SLAT)

The SLAT is a potential new assessment tool based on the size vs BSA of patch, plaque, or tumor lesions, something previously alluded to by the Tri-Societies as a potential tool for tracking tumor lesions in MF that are inadequately measured by BSA.8 The SLAT score is the sum of the (area × 1, 2, or 4 weighting factor) of all cutaneous lesions, first in a given nodal drainage area as shown in Figure 2 and then a total sum of all lesions in all areas of the body (Table 5). The SLAT score has yet to be used in clinical trials for approval of new agents, but once acknowledged, it may prove particularly useful in facilitating staging of the non-MF/non-SS PCLs, which rely on size of lesions in nodal drainage areas of the skin. It may also be useful in tracking skin changes in the non-MF/non-SS PCLs, which usually have primarily or solely tumor lesions, to prevent overestimation of size by percentage of BSA.

Target lesion scoring

Target lesion scoring has utility where the purpose is to monitor the effect of local treatment of selected lesions. If there are multiple lesions, the largest and/or most representative of current disease should be chosen as target lesions. The Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity (CAILS)7,32 involves grading up to 5 index lesions each for (1) erythema, scale, plaque elevation, and hypo- or hyperpigmentation on a 0 to 8 scale and (2) size (longest diameter [LDi] times longest axis perpendicular to LDi [short diameter or SDI]), using this actual size to then assign a number based on a categorical range of sizes. A lesion score based on the summation of all the individual parameter grades is generated and all lesion scores are added together for a total CAILS score. A modified CAILS score eliminating pigmentation has been used in sponsored clinical trials.

LN assessment

LNs are classified by pathological staging. The definition of lymphoma in LNs by pathological assessment should be according to current guidelines and outlined in the study design. Modifications to the LN staging of MF/SS are noted in Table 2. In MF/SS, the pathological assessment of nodal lymphoma should fulfill the criteria for N3 designation. During a clinical trial, the target LNs of interest are those >1.5 cm LDi by imaging and confirmed as lymphoma by prior or concurrent biopsy of a representative LN. If a clone in LN or viscera is detected but different from that identified in the skin, another concurrent lymphoproliferative process should be considered.

Imaging

For a clinical trial that requires a global TNM(B) response assessment, imaging is recommended regardless of T classification to document presence or absence of extracutaneous disease at study start. Optimal timing of imaging for a clinical trial would be within 30 days of onset of study treatment. A prior imaging study within 3 months may be used if low risk of progression (ie, early stage or indolent PCL with no prior history of extracutaneous disease) and no significant change by physical exam or laboratory examination has occurred since the prior imaging study.

Choice of type of imaging

An individual patient in a given clinical trial should have LNs assessed by the same imaging criteria and technique throughout the clinical trial unless a medical contraindication arises. The Lugano classification recommends staging [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid lymphomas by PET-CT (with or without a dedicated CT) and variably FDG-avid lymphomas by CT. All PCLs other than marginal zone lymphoma, including MF/SS,33-35 are relatively PET avid. Although to date, all FDA-approved medications for MF/SS have used CT-based size of LNs for nodal assessment, data support assessment of extracutaneous disease in MF/SS by PET-CT if study design permits.33-35 PET-CT (without a diagnostic CT) gives metabolic information in addition to size, whereas radiation dose exposure, an important consideration with repeated scans, is comparable to a diagnostic quality CT.36,37 In those patients allergic to contrast, in which size of LNs are being used to assess response, one can either prescribe appropriate therapeutic measures immediately preparatory to imaging or use magnetic resonance imaging. PET-CT or CT scan at a minimum should provide imaging of neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

LN assessment methods

For all PCLs, the LN assessment is according to the findings on imaging as outlined in the Lugano classification unless otherwise specified by trial design. All LNs chosen as target LNs must meet the same standards for assessment and response. Until further data are available on metabolic response by PET-CT in PCL, the preferred method of assessment of target LNs is by the product of the perpendicular diameters (PPD) (LDi × SDi) of up to 6 of the largest target nodes >1.5 cm LDi, preferentially from different body regions representative of the patient’s overall disease burden. However, if clinical trial design dictates, assessment of LNs by metabolic data from PET-CT scans should use the Lugano classification or the most current published methodology accepted by the Tri-Societies. The Lugano classification currently utilizes the following 5-point scale: 1 = no FDG uptake > background; 2 = FDG uptake ≤ mediastinum; 3 = FDG uptake > mediastinum but < liver; 4 = FDG uptake moderately > liver; 5 = FDG uptake markedly > liver and/or new lesions. Use of PET-CT for all PCLs is encouraged to expand knowledge regarding optimal imaging modalities in these diseases.

Biopsy

The pathologic assessment of an abnormal representative LN may be assumed to apply to all abnormal peripheral and central LNs in a given patient as long as there is no other alternative clinical diagnosis. If accessibility or risk is not an issue, the largest peripheral LN draining an area of involved skin, the one with the most concerning morphological features on imaging, and, if PET data are available, the one that shows the highest standardized uptake value38 are helpful features in choosing the most representative LN for biopsy. Pathologic assessment should include at a minimum light microscopy, immunophenotyping including immunohistochemistry, and in most cases, flow cytometry and molecular methods.

The standard for diagnosis, subtyping, and grading of nodal lymphoma, when feasible, is an excisional LN biopsy, but a core needle biopsy (CNB) of a representative abnormal LN may suffice in certain circumstances. Suggestions to enhance the diagnostic yield of CNB are given in Box 2.39-41

CNB of lymph nodes

Although an excisional LN biopsy is the gold standard for assessing involvement in PCL, a CNB of a representative abnormal LN (selected by size and metabolic data if available), despite its inherent limitations on the ability to assess architectural features, has the advantage over an excisional biopsy of a reduction in cost, postprocedural complications, and time to diagnosis and is particularly attractive for use in clinical trials. There is data on CNB for determining N-classification and stage in CTCL39 but no similar data in CBCL. However, studies in nodal lymphoma suggest 90% sensitivity of CNBs compared with post-CNB excisional LN biopsies, the main concern being false negatives.39,40 CNB represents an acceptable form of LN staging where excisional biopsy is inadvisable or not otherwise feasible, provided that adequate representative material for evaluation is present and other supportive features, such as standardized uptake value on PET-CT or clinical findings, are in accord.

The main factors affecting the diagnostic capabilities of a CNB are procurement of adequate tissue for all standard and ancillary assessments, the status of the biopsy (ie, free of crush artifact, necrosis, or hemorrhage) and ability to capture key features of the lymphoma subtype. The following are suggestions to improve the potential for a diagnostic CNB biopsy39-41 but are not meant to dictate clinical practice:

- 1.

Ultrasound or CT guidance

- 2.

3 or 4 cores of sufficient diameter and depth

- 3.

Pathologic assessment that includes light microscopy, immunophenotyping including immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, and molecular methods (eg, clonality, pathogenic genomic variants). Ideally, biopsies should be read by hematopathologists with experience in both excisional and core nodal biopsies in PCLs.

- 4.

If core biopsy material is not sufficient for all necessary tests for diagnosis/staging, an additional core biopsy or fine needle aspirate from the same LN or nodal area may be used to procure further tissue. If the core LN biopsy is nondiagnostic, if there is a discrepancy between aggressive clinical features and benign histological findings, or if the study protocol requires a firm pathological assessment of enlarged LNs, an excisional biopsy should be performed.

It is recommended that patients with LNs designated collectively as Nx (ie, those patients with radiologically abnormal LNs who have never had a representative abnormal LN biopsied, had an earlier biopsy of a representative node that was equivocal pathologically, or have experienced a significant increase in LN size since a prior negative biopsy for lymphoma) have a representative LN biopsy prior to study entry to determine nodal status. However, if patients with Nx LNs are included in clinical trials, the imaging technique and methodology used to assess the response in LNs should be the same as those used to assess the response in patients whose LNs have been pathologically staged but their results tracked separately. Only MF/SS is unique in having rigid categorical pathological guidelines for lymphomatous involvement in lymph nodes (Table 2). All other PCLs have the diagnosis of lymphoma in lymph nodes made by standard histopathological assessment.

Assessment of viscera

The recommendation for type of imaging is as for LN evaluation. An individual patient in a given clinical trial should have viscera assessed by the same imaging criteria and technique throughout the clinical trial unless a medical contraindication arises. The Mx classification may be used in situations where visceral involvement is suspected but neither confirmed nor refuted by available pathologic or imaging assessment. Trial design will dictate whether patients with Mx classification should be included in clinical trials.

It is recommended that a BM biopsy be performed at screening/baseline (BL) in any patient with a PCL who has unexplained hematologic abnormalities. A BM biopsy may also be trial-specific for certain PCLs but is not standard for staging or classification of MF/SS. All patients with PCL in whom a BM core biopsy shows a nodular, diffuse, or interstitial involvement (>5% of BM cellularity) and where the immunophenotype and molecular findings are consistent with that of the skin PCL will be considered to have marrow involvement, classified as M1, and if included in clinical trials of PCLs, their response considered separately. Patients with MF or SS with a positive BM biopsy (defined as above) but no visceral disease would be classified as M1A and those with any visceral disease as M1B. Although response in BM in PET-avid systemic lymphomas may be assessed per Lugano guidelines, data are needed for PET-avid PCLs.

Assessment of abnormal lymphocytes in blood (MF/SS or adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma)

The same methodology for assessment of blood tumor burden should be used for all patients throughout a clinical trial. Data from different methods of assessing blood involvement may not be combined or compared for response assessment. Flow cytometric analysis is the preferred method to establish the specific phenotype of the aberrant lymphocyte population and to classify blood tumor burden. It should be done at study entry8,42,43 and repeated at the same times of skin exam if global response is to be determined.

The specific method of determining the number of abnormal lymphocytes by flow cytometry should be outlined at the outset of the trial. The absolute number of immunophenotypically abnormal lymphocytes should be used to determine B classification for clinical trials.7,8,42 The absolute value is determined by the percentage of aberrant lymphocytes identified on flow cytometry multiplied by the total lymphocyte count of the CBC but may also be calculated by determining the percentage of aberrant CD45+ leukocytes/white blood cell count identified on flow cytometry multiplied by the white blood cell count. In any study, one method of determining absolute counts of aberrant lymphocytes should be defined at the time of study planning. Neither CD4/CD8 ratio or the percentage of abnormal lymphocyte subsets should be used alone to define B classification. For clinical trials of MF/SS where flow cytometry is not available or patients are deemed to be other than CD4 positive, the potential use of Sézary cell counts or other means of assessment of blood involvement should be determined at study onset.

Patients with lymphopenia (defined as <1000 absolute lymphocytes) may potentially have an underestimation of aberrant lymphocyte burden if assessed only by the absolute number and not also by the percentage of immunophenotypically abnormal lymphocytes. If patients with lymphopenia at baseline are included in a clinical trial, study design should first address if there will be any modification of assessment of blood tumor burden and/or determination of blood and global response for these patients vs those without lymphopenia and whether their response data may be reported in aggregate with that of the other patients.

For a clinical trial, determination of blood clonality is only necessary if required by study protocol, to confirm B2 blood involvement, or if molecular CR is a potential goal. When performed, clonality testing by molecular assessment in the blood should be done by the same method as used to determine clonality in skin and outlined at study entry. A different clone in the blood from that in the skin is not considered disease related.

Pruritus assessment

“Significant improvement in pruritus,” “pruritus relief,” or “resolution of pruritus” as a secondary endpoint has been noted in several trials with arbitrary designation of what constitutes pruritus severity and significance of change. To be meaningful for patients, such terminology should be defined at study onset, including the tool used to measure pruritus, its correlation with QoL assessment, and stipulation that other treatments that can affect pruritus (such as antihistamines or topical/systemic steroids) have been present prior to study screening and no increase in dose or dosing frequency has occurred during the trial.

Response assessment

Response in skin

Global response score is driven by the response in skin (Table 6).8 All responses should be documented to be at least 4 weeks in duration, and if visits are spread out greater than monthly and the patient fails to maintain a new PR, CR, or progressive disease (PD) on return at a period later than 4 weeks, no new response should be recorded. If objective response (OR) duration is an endpoint in the study, direct patient assessment is recommended no less frequently than monthly to avoid overestimation of the duration of any OR. If confirmed at 4 weeks by repeat assessment, response in skin should be noted/begin at time of response. Response in skin is defined in Table 7.

We introduce the term “very good partial response” (VGPR), which is meant to convey a meaningful degree of improvement in the skin beyond the 50% improvement standard definition of PR. VGPR for PCL is defined here as 90% to <100% clearance of skin disease, and in patients with MF/SS, all lesions must also be patch/plaque in nature and total BSA <10%. Although it is possible that a lower percentage improvement may have clinical impact, ≥90% improvement in the serum M-protein in myeloma,44 90% improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score in psoriasis,45 and 90% improvement in the Severity of Alopecia Tool score in alopecia areata46 have been associated with a more rapid onset and/or longer duration of OR. The duration of a VGPR may have particular relevance for early MF.

Response in lymph nodes

For a clinical trial addressing response in skin only, no further imaging is required unless new LN or visceral involvement is suggested by symptomatology, physical exam, or laboratory testing. Because response in skin drives global response in the PCLs, timing of repeat imaging should be related to a confirmed response in skin or a question of PD in LNs or viscera. If repeat imaging studies done in response to OR in the skin reveal no findings that would affect the global response, the time of determination of global OR starts when the OR was first noted in the skin. However, if imaging studies reveal findings that would change the global response based on skin assessment alone, then the time of global response starts when all compartments have response documented.

Response in LNs should be according to Lugano criteria for imaging11 (Table 8). If determination of nodal response is by LN size, for nodes ≤1.5 cm in LDi prior to baseline, they must increase to >1.5 cm and increase by ≥50% from PPD nadir to be considered PD unless biopsy proves otherwise. This definition of PD specifically prevents the 10% to 20% standard error in imaging47-49 from creating an erroneous response of PD in LNs of 1 to 1.4 cm LDi that show minimal enlargement. If determination of nodal response in PET-CT is by metabolic score, the recommendations of the Lugano classification, or any published update that is accepted by the Tri-Societies, should be used. The protocol should define a priori the determinants of PD and CR for patients with Nx nodes. However, it is reasonable to consider a global response of CR with NX nodes that otherwise meet CR criteria and to group their response accordingly with those whose nodes have been pathologically determined. Because inflammatory changes may persist for some time after discontinuation of chemotherapy, the International Harmonization Project suggests at least 3 weeks off of any chemotherapy before repeating a PET-CT to decrease the influence of postchemotherapy inflammatory changes that could potentially lead to misinterpretation of overall response.50 Metabolic assessment of response in LNs by PET-CT also can be problematic in immunotherapy trials where the observation of increased metabolic activity can be mistakenly interpreted as progressive disease. Presently, the modified Lugano classification notes that in these trials, an increase in FDG avidity alone does not constitute PD without a concomitant increase in LN size that meets PD criteria.51,52

Response in viscera

Response in blood (MF and SS only)

In the event of a PR or CR in skin where global response is to be determined (Table 10), blood assessment should be done within 1 week of skin evaluation and repeated within 4 weeks at the time of confirmation skin response. In patients with a global CR, confirmation of a “molecular CR” in blood is desirable when feasible. The method used to determine presence or absence of molecular disease in blood should be outlined at study entry and considered experimental until validated in PCL.

Response in pruritus

Any claim of response in pruritus must have persisted for at least 4 weeks.

Endpoints

It should be noted that not all regulatory agencies have the same definition for response criteria and endpoints (eg, different definitions of PD by the FDA and the European Medicines Agency). Ideally, the differences should be resolved for studies being carried out in different countries under different regulatory agencies as this may affect the ability to combine study results. Various endpoints and their definitions and utility are noted in Table 11. Endpoints should be matched to the study population and trial duration.

In situations where disease signs and symptoms or therapeutic interventions have a negative impact on a patient’s quality of life, these QoL assessments may assume greater importance than short-term goals such as PR status. QoL assessment should be considered in all clinical trials for PCLs and would be expected to improve with treatments designated as having an OR. A novel suggestion in trials of low-grade disease or those emphasizing maintenance vs improvement of disease burden is to combine QoL assessment with duration of response in an endpoint termed “objective clinical benefit ‘X’ months,” where X refers to what is considered a significant duration of response. Further work is needed to standardize the particular QoL score used and to validate a meaningful duration of response for a given type and stage of PCL.

Conclusions

Internationally accepted standardized criteria for evaluation, staging, classification, study design, endpoints, and response criteria for all the PCLs are critical. Harmonizing these guidelines will facilitate the conduct of informative and comparable clinical trials, allow collation of study results from various centers, foster metanalyses, and hasten the creation and approval of new effective treatments for these PCLs. These guidelines represent a collaborative consensus opinion of international experts in cutaneous lymphoma, but the final study design may require adaptation according to trial aims and PCL subtypes, local logistics, and regulatory necessities.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors contributed to the creation, clarification, and/or revision of all recommendations for the clinical trial design, assessment, response criteria, endpoints, and update in staging of cutaneous lymphomas as recommended in this paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.H. provided research support for ADC Therapeutics; Affimed; Aileron; Celgene; Crispr Therapeutics; Daiichi Sankyo; Forty Seven, Inc.; Kyowa Hakko Kirin; Millennium/Takeda; Seattle Genetics; Trillium Therapeutics; and Verastem/SecuraBio and consulted for Acrotech Biopharma; ADC Therapeutics; C4 Therapeutics; Daiichi Sankyo; Janssen; Kura Oncology; Kyowa Hakko Kirin; Myeloid Therapeutics; ONO Pharmaceuticals; Seattle Genetics; SecuraBio; Shoreline Biosciences, Inc.; Takeda; Trillium Therapeutics; Tubulis; and Vividion Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Elise A. Olsen, Box 3294 Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710; e-mail: elise.olsen@dm.duke.edu.