Key Points

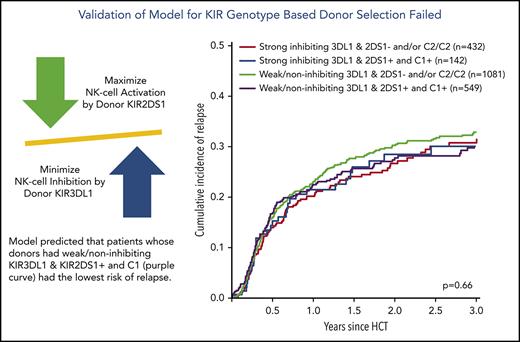

KIR2DS1/KIR3DL1 genotype-informed selection of unrelated stem cell donors is not ready for routine use.

Deeper knowledge of NK-mediated alloreactivity is necessary to predict and optimize its contribution to graft-versus-leukemia reactions.

Abstract

Several studies suggest that harnessing natural killer (NK) cell reactivity mediated through killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) could reduce the risk of relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Based on one promising model, information on KIR2DS1 and KIR3DL1 and their cognate ligands can be used to classify donors as KIR-advantageous or KIR-disadvantageous. This study was aimed at externally validating this model in unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. The impact of the predictor on overall survival (OS) and relapse incidence was tested in a Cox regression model adjusted for patient age, a modified disease risk index, Karnofsky performance status, donor age, HLA match, sex match, cytomegalovirus match, conditioning intensity, type of T-cell depletion, and graft type. Data from 2222 patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome were analyzed. KIR genes were typed by using high-resolution amplicon-based next-generation sequencing. In univariable analyses and subgroup analyses, OS and the cumulative incidence of relapse of patients with a KIR-advantageous donor were comparable to patients with a KIR-disadvantageous donor. The adjusted hazard ratio from the multivariable Cox regression model was 0.99 (Wald test, P = .93) for OS and 1.04 (Wald test, P = .78) for relapse incidence. We also tested the impact of activating donor KIR2DS1 and inhibition by KIR3DL1 separately but found no significant impact on OS and the risk of relapse. Thus, our study shows that the proposed model does not universally predict NK-mediated disease control. Deeper knowledge of NK-mediated alloreactivity is necessary to predict its contribution to graft-versus-leukemia reactions and to eventually use KIR genotype information for donor selection.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells may contribute to early disease control and remission induction soon after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Clinical evidence for this hypothesis comes from clinical trials conducted by several independent groups, which showed that NK cell transfusion may induce complete remissions in patients with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1-5 Furthermore, several groups reported associations between the risk of relapse after allogeneic HCT and the predicted NK alloreactivity.6-8

NK cells may kill target cells depending on the integration of activating and inhibitory signals received through a variety of cell surface receptors. Among them, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), whose cognate ligands are HLA class I molecules, play a major role. Different models for NK cell activation apply to specific transplant settings: In the setting of HLA class I mismatched HCT, the missing-self hypothesis provides a consistent explanation for NK-cell activation. If inhibitory KIRs do not encounter their cognate ligands on target cells, NK cells may become activated and kill their targets. Clinical evidence for this hypothesis was published by a group of researchers from Perugia in the early 2000s.9,10

To explain KIR-mediated alloreactivity in HLA-compatible transplantation, the missing-self hypothesis alone is not sufficient. Patients and donors do not differ in this setting with respect to their ligands for KIRs, namely HLA class I molecules. Changes of the NK-specific recognition pattern particular to the leukemic cells are assumed to elicit NK-mediated alloreactivity. Indeed, such changes have been described by several groups, although conflicting data have been reported with respect to the downregulation or loss of HLA class I molecules at diagnosis and relapse of AML.11-13 Such phenotypic changes of cancer cells mirror changes of virus-infected cells to some degree.14,15 Notably, studies also found that individuals with distinct KIR/KIR–ligand combinations have lower HIV infection rates and slower AIDS progression.14,16,17

Building on these data, an advanced receptor–ligand model was developed to predict outcome after allogeneic HCT for patients with AML. This model essentially adopts the idea that a donor KIR gene repertoire which optimizes signaling through activating KIRs and minimizes signaling through inhibitory KIRs may reduce the risk of relapse.18,19 The final model incorporated information on the KIR2DS1 gene status in addition to the expression level of KIR3DL1 alleles and their binding affinities to their dimorphic ligand Bw4.17,20

Relapse after allogeneic HCT is a major cause of treatment failure. The reduction of this risk by educated donor selection would therefore be highly warranted. KIR genes are especially attractive for advancing donor selection because the donor KIR genotype would be sufficient to predict outcome when the patient’s HLA is known. The goal of the current study was to validate one advanced KIR receptor–ligand model with potential for predicting relapse risk after allogeneic HCT for patients with AML based on information on donor KIR2DS1, KIR3DL1, and their cognate ligands.19

Methods

Inclusion criteria

We conducted a retrospective study on the impact of KIR genotype information on patients who were registered with Deutsches Register für Stammzelltransplantationen (DRST). This registry plays a major role in the data collection process of the European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) in Germany. All patients whose data were analyzed in this study had provided written informed consent for the use of their medical data for research purposes. Furthermore, all stem cell donors had provided written informed consent when they contributed a sample to the Collaborative Biobank (www.cobi-biobank.de). The study was approved by the ethical committee responsible for the biobank at the TU Dresden and the institutional review board of the DRST. Additional patient inclusion criteria were first unrelated allogeneic HCT between January 2005 and December 2017, a diagnosis of AML or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and age >18 years. All donor–recipient pairs with three or more mismatches at HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, or HLA-DQB1 were excluded.

Sample identity

Donor information was mapped to the medical data of the patient using the donor identifier as a key. We succeeded in linking information for 2304 donor–recipient pairs. To rule out mistakes during this process, all donor samples were typed for HLA and KIR genes. Information on the HLA type was used to double-check the sample identity by comparing the typing result vs the original typing results for that donor and by checking HLA compatibility with the corresponding patient information.

KIR genotyping

Genotyping was performed by using a high-resolution, short amplicon–based next-generation sequencing workflow. KIR typing at the allele level was based on sequencing of exons 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 9 and subsequent bioinformatic analysis as previously described.21

Data preparation

HLA-C alleles were grouped in C1 and C2 ligands and B alleles were grouped into Bw4-80I/Bw-80T/Bw6 epitopes based on information retrieved from https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/kir/ligand.html. Expression levels of KIR3DL1 alleles were classified according to Boudreau et al19 into high, low, or null. Information on KIRs and their cognate ligands was grouped according to the studies by Venstrom et al18 and Boudreau et al.19

Data from 23 donor–recipient pairs were excluded because sample identity could not be unequivocally confirmed. Typing of 59 samples failed due to quality controls indicating that DNA was too low in quantity or quality for the workflow. The final analysis set thus contained information on 2222 patients. HLA compatibility between donors and recipients was assessed based on information for two fields for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, and HLA-DQB1. The type of AML was grouped according to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia.22 AML in patients with a documented history of myelodysplasia was considered as secondary AML after MDS. Using information available on the genetic risk and disease stage at transplantation from EBMT Minimal Essential Data Forms A and B, we calculated a simplified Disease Risk Index (DRI) for AML and MDS. For this purpose, cytogenetic risk was classified according to the rules for the refined DRI23 except for chromosome 17p abnormalities, which were assigned to the adverse risk group. For patients with missing stage, disease, or cytogenetic risk information, DRI group was imputed based on frequencies reported in the publication of the refined DRI. The intensity of conditioning regimens was classified according to working definitions of EBMT and the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research.24

Primary endpoint and power considerations

Overall survival was selected as the primary endpoint because this factor is very informative for decision-making and is objective. The impact of weak or noninhibiting donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations vs strong inhibiting donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations in the context of HLA-compatible allogeneic HCT had been estimated by a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.84 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72-0.98) for overall mortality by Boudreau et al.19 During the design phase of the current study, we calculated that data from 2123 patients with 1372 events were required to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in overall survival between the 2 KIR groups given the HR of 0.84, a proportion of strong inhibiting donors of 25%, a type I error of 5%, and a power of 80%.

Statistical analysis

Relapse or progression was selected as the major secondary endpoint. Additional endpoints were nonrelapse mortality and event-free survival. Death, relapse, and progression (whichever occurred first) were defined as events for event-free survival. Death without previous relapse or progression was defined as nonrelapse death. Incidence of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and death were considered as competing risks. Events for the composite endpoint, GVHD-free/relapse-free survival, were death, relapse, acute GVHD grades III and IV, and extensive chronic GVHD. All time-to-event endpoints were evaluated in multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models. Relapse/progression and nonrelapse mortality and incidence of GVHD were considered as competing risks and were analyzed by using cumulative incidence curves and cause-specific Cox regression models. In addition to the classifiers of interest, the multivariable models contained information on the patients’ Karnofsky performance status, age, sex, cytomegalovirus serostatus, disease risk index, conditioning intensity, T-cell depletion, HLA-matching, donor age, donor sex, and donor cytomegalovirus serostatus. Because no significant interaction effects between these covariates and any classifiers of interest have been identified, the Cox models contained only main effects. The effects are reported as HRs with 95% CIs.

The proportionality assumption was checked for each covariable for the main models analyzing overall survival and relapse by means of plots of scaled Schoenfeld residuals and the test of Grambsch and Therneau.25

Results

Characteristics of the patient cohort

Clinical data from 2222 patients were analyzed. The median age at allogeneic HCT was 59.3 years (range, 18.1-79.6 years). Indication for allogeneic HCT was AML for 80% of patients and MDS for 20%. Disease risk was assessed as intermediate, high, or very high in 59%, 41%, and 0.3%, respectively.

Patient and donor pairs were 10/10 matched in 78% of pairs, whereas a one locus mismatch was reported for 22% of pairs. Donor HLA-B mismatches translated into a constellation of patients with missing inhibitory KIR3DL1-ligands in only 8 donor–recipient pairs (0.4% of all pairs).

Myeloablative, reduced-intensity, and nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens were used in 20%, 76%, and 4% of patients, respectively. Antithymocyte globulin (ATG) was administered in 78% of patients and alemtuzumab in 2%. Nineteen percent of patients received no T-cell depletion, and 1% received an ex vivo T cell–depleted graft. Peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) and bone marrow were used as graft source in 96% and 4% of patients. Further details and the distribution of patient characteristics for 2 major subgroups defined by using donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations are given in Table 1.

For the whole cohort, 2-year probabilities were 52% (95% CI, 50-55) for overall survival, 45% (95% CI, 43-48) for event-free survival, 29% (95% CI, 27-31) for relapse incidence, and 26% (95% CI, 24-28) for nonrelapse mortality. In total, 566 relapses and 952 deaths were recorded. This number of events translated into a power of 65% for the statistical comparison of mortality among patients with noninhibiting or weak inhibitory donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations vs strong inhibiting donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations.

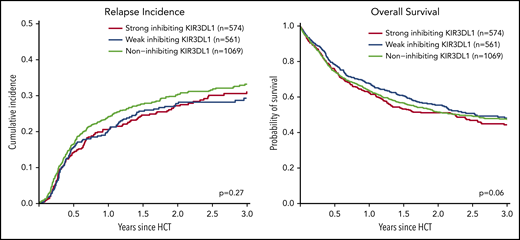

Impact of KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations

We analyzed the impact of strong inhibiting, weak inhibiting, and noninhibiting (classification in 3 groups) and of strong inhibiting vs weak/noninhibiting (classification in 2 groups) KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations on outcome after transplantation. Univariable comparisons for the classification into 3 groups showed almost superimposable curves for the cumulative incidence of relapse and survival (Figure 1), and multivariable Cox regression modeling revealed no significant impact (Table 2). Because different receptor–ligand combinations had to be collapsed for the 3-group and 2-group models, we additionally analyzed the impact of all possible combinations of the compound KIR-expression level (high, low, or null) and its cognate compound ligand (Bw4-I, Bw4-T, and Bw6). Compared with the group for which the strongest inhibition of NK alloreactivity and thus the highest incidence of relapse was predicted by the model (ie, patients who expose the strong ligand Bw4-I with donors who have highly expressed KIR3DL1), we did not find any subgroup with a lower incidence of relapse (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site).

Impact of donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations on relapse incidence and overall survival. This figure shows the univariate comparisons for the cumulative incidence of relapse (left panel) and overall survival (right panel) in the framework of the 3-group model of patients classified based on their donors’ KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations according to Boudreau et al.19 The P values represent the score tests of univariate Cox regression models.

Impact of donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations on relapse incidence and overall survival. This figure shows the univariate comparisons for the cumulative incidence of relapse (left panel) and overall survival (right panel) in the framework of the 3-group model of patients classified based on their donors’ KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations according to Boudreau et al.19 The P values represent the score tests of univariate Cox regression models.

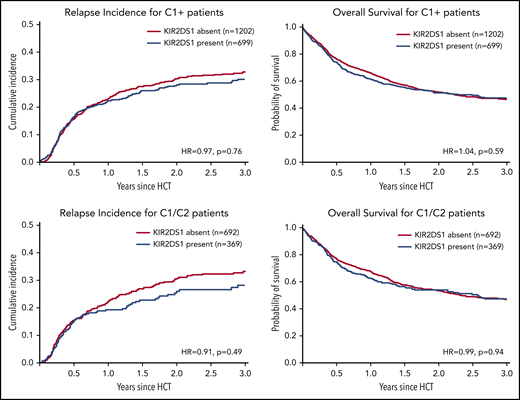

Impact of KIR2DS1/C1C2 epitope combinations

We next analyzed the impact of donor KIR2DS1 and C1/C2 epitope combinations. Venstrom et al18 reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2012 that patients with KIR2DS1-positive donors with at least one C1-ligand had a lower risk of relapse (HR, 0.71; P = .009) compared with patients with only C2-ligands or KIR2DS1-negative donors. In multivariable analysis, however, we found no significant impact of activating vs nonactivating KIR2DS1 on the risk of relapse (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.81-1.17; P = .8) or overall survival (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.91-1.21; P = .5). Results for further comparisons integrating information on donor KIR2DS1 absence or presence are shown in Table 2.

In line with the idea that NK-mediated alloreactivity can be enhanced by selecting KIR2DS1-activating receptor–ligand combinations, additional subgroup analyses were performed: KIR2DS1-positive NK cells acquire tolerance in individuals homozygous for C2.26 Furthermore, patients homozygous for C1 cannot benefit from KIR2DS1-positive donors because their tumor cells do not express the activating ligand for KIR2DS1. We thus hypothesized that the impact of donor KIR2DS1 positivity would be most pronounced in C1/C2 patients. However, as shown in Figure 2 (also in 1061 C1/C2-positive patients), KIR2DS1 presence did not have a significant impact on the risk of relapse (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.70-1.18; P = .49) or on mortality (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.81-1.21; P = .94).

Impact of donor KIR2DS1 in C1-positive patients. This figure shows the cumulative incidences of relapse (left panels) and overall survival (right panels) of patients grouped according to their donors’ KIR2DS1-status (absence vs presence) and according to the patients’ C1/C2-ligand status. The upper panels show outcomes of C1-positive patients (ie, C1/C2 or C1/C1 patients). The lower panels show outcomes of C1/C2-positive patients only. This subgroup of patients whose leukemia cells express C2, the activating ligand for KIR2DS1, should have the greatest benefit of KIR2DS1-positive donors. Patients were classified according to the algorithm published by Venstrom et al18 in 2012. The HRs were calculated in multivariable Cox regression models adjusted for patient age, donor age, disease risk index, Karnofsky performance status, sex match, cytomegalovirus match, HLA match, conditioning intensity, T-cell depletion, and stem cell source. The P values represent the Wald tests.

Impact of donor KIR2DS1 in C1-positive patients. This figure shows the cumulative incidences of relapse (left panels) and overall survival (right panels) of patients grouped according to their donors’ KIR2DS1-status (absence vs presence) and according to the patients’ C1/C2-ligand status. The upper panels show outcomes of C1-positive patients (ie, C1/C2 or C1/C1 patients). The lower panels show outcomes of C1/C2-positive patients only. This subgroup of patients whose leukemia cells express C2, the activating ligand for KIR2DS1, should have the greatest benefit of KIR2DS1-positive donors. Patients were classified according to the algorithm published by Venstrom et al18 in 2012. The HRs were calculated in multivariable Cox regression models adjusted for patient age, donor age, disease risk index, Karnofsky performance status, sex match, cytomegalovirus match, HLA match, conditioning intensity, T-cell depletion, and stem cell source. The P values represent the Wald tests.

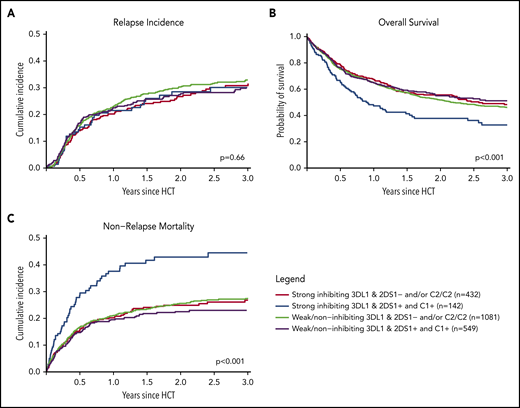

Combined classifier based on donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtypes and KIR2DS1/C1C2 epitopes

Finally, we combined information on activating or nonactivating KIR2DS1 combinations based on the patients’ C2-ligand status and the corresponding donors’ genotype status and information on strong inhibiting, weak inhibiting, and noninhibiting KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype pairs according to Boudreau et al.19 This model predicts KIR2DS1-activating/KIR3DL1 weak/noninhibiting pairs to have the lowest risk of relapse and KIR2DS1-nonactivating/KIR3DL1 strong inhibiting pairs to have the highest risk of relapse, and the 2 remaining groups to have results in-between. The distribution of donor–recipient pairs among the respective KIR receptor–ligand groups is shown in Table 2. In the current study, the cumulative incidences of relapse of the 4 groups were almost superimposable (P = .66) (Figure 3A). Although we observed a significantly different overall survival between the 4 groups (log-rank test, P < .001), with the small group of KIR2DS1-activating/KIR3DL1 strong inhibiting pairs having the worst outcome (Figure 3B), this difference in overall survival was caused by higher nonrelapse mortality (Figure 3C), which was not predicted by the model. Information taken from multivariable Cox regression modeling to account for potential covariable imbalances (Table 2; supplemental Table 1) did not change the pattern of results. To explore the reason for the difference in overall survival, we performed analyses on two additional endpoints, incidence of acute GVHD grades II to IV and GVHD-free/relapse-free survival (supplemental Table 2). These exploratory analyses revealed no impact of donor KIR genotype–based classifications on the risk of GVHD.

Impact of donor KIR2DS1 and KIR3DL1 combinations on relapse incidence, overall survival, and nonrelapse mortality. The graphs show the outcome of patients who were grouped according to their donors’ KIR2DS1 status (activating vs nonactivating) and KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations (strong inhibiting vs noninhibiting/weak inhibitory) in terms of relapse incidence, overall survival, and nonrelapse mortality. Patients were classified according to the algorithm published by Boudreau et al.19 The P values represent the score tests of univariate Cox regression models.

Impact of donor KIR2DS1 and KIR3DL1 combinations on relapse incidence, overall survival, and nonrelapse mortality. The graphs show the outcome of patients who were grouped according to their donors’ KIR2DS1 status (activating vs nonactivating) and KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations (strong inhibiting vs noninhibiting/weak inhibitory) in terms of relapse incidence, overall survival, and nonrelapse mortality. Patients were classified according to the algorithm published by Boudreau et al.19 The P values represent the score tests of univariate Cox regression models.

Impact of absence/presence of donor KIR3DS1

Finally, we analyzed the potential impact of KIR3DS1 presence on the risk of relapse and death after transplantation. Cumulative incidences of relapse, nonrelapse mortality, and overall survival were not different when outcomes were compared between patients with KIR3DS1-positive or KIR3DS1-negative donors (Table 2; supplemental Figure 2). Furthermore, no difference for the incidence of acute GVHD grade II to IV with onset up to day +100 post-HCT was found for the comparison of KIR3DS1 absence vs presence (supplemental Table 2). In contrast to what has been reported before, we found a slightly higher incidence of acute GVHD grades II to IV within 100 days after HCT among patients having a donor with 2 KIR3DS1 genes compared with patients with KIR3DS1-negative donors (34% vs 29%; P = .3).

Subgroup analyses

We performed exploratory subgroup analyses in patients characterized according to features similar to the original population analyzed by Venstrom et al18 and Boudreau et al.19 Thus, subgroup analyses were performed for young patients, patients with AML, patients who had received total body irradiation, patients who had received myeloablative conditioning regimens, patients who had not received in vivo or ex vivo T-cell depletion, and patients with 10/10 HLA-matched donors as well as patients with partially matched donors (supplemental Table 3). We also analyzed the largest homogeneous subgroup of patients (N = 1067) who received PBSC from HLA 10/10 matched unrelated donors after reduced-intensity conditioning and ATG as GVHD prophylaxis. Patients aged <50 years exhibited the predicted pattern of results; that is, a lower risk of relapse (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.48-1.04) translating into a lower risk of mortality (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.54-1.08) for patients whose donors had activating KIR2DS1. However, for different KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations, the predicted outcome pattern in this subgroup was not observed. In no other subpopulation was the predicted pattern of results observed.

Discussion

This large retrospective study failed to replicate findings from 2 important studies that were aimed at identifying donors who could reduce the risk of relapse based on their KIR2DS1 and KIR3DL1 genotypes.18,19 In accordance with the original publications, we grouped donors according to their KIR3DL1 allele–Bw4 epitope combinations, following the idea that lower average expression of KIR3DL1 and lower binding affinity translate into less inhibition and lead to less relapse. However, we did not observe the expected outcomes in terms of relapse and overall survival (Figure 3). Furthermore, we could not find the predicted impact of KIR2DS1-positive donors whose 2DS1-positive NK cells were not muted in the context of a C2/C2 HLA-C background.18,26 This was also true for the subgroup of C1/C2 heterozygous patients whose leukemic cells express the activating ligand for KIR2DS1.

The study missed the target power of 80% to detect the assumed effect on mortality after allogeneic HCT for patients with noninhibiting/weak inhibitory donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations vs strong inhibiting donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations due to a lower number of events than expected. However, the patient number was ∼1.7-fold greater than that of the original studies, and the post hoc power was 65%. Furthermore, the relapse pattern (Figure 3) did not indicate that the study failed due to a lack of power. In turn, the strength of this study lies in its rigorous statistical approach to validate a prespecified hypothesis in an independent cohort. Its failure teaches once more about the need for external validation studies.27,28

One hypothesis for the failed validation of the reported findings is that the patient characteristics and transplant procedures of the study cohorts were different (supplemental Table 4). The current study used German data from a contemporary cohort of patients who received their first HLA-compatible unrelated donor transplant for AML or MDS. Key characteristics of the transplant procedure in our cohort comprised chemotherapy-based, reduced-intensity conditioning, PBSC grafts, and ATG-based GVHD prophylaxis for the majority of patients in contrast to the original study, for which the impact of donor KIR3DL1/KIR2DS1 had been reported: patients were almost 20 years younger and had received total body irradiation–based myeloablative conditioning, no ATG for GVHD prophylaxis, and bone marrow as the graft source.18,19 Because our cohort was almost twice as large compared with the original cohort, we performed exploratory subgroup analyses for patients with AML, younger patients, total body irradiation–based conditioning, myeloablative conditioning, GVHD prophylaxis without T-cell depletion, those with 10/10 HLA-matched donors, and those with partially matched donors to mirror the characteristics of the original patient cohort. None of these subgroups showed the predicted pattern of results, except for patients aged <50 years, who exhibited the predicted pattern for activating KIR2DS1 but not for the donor KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtype combinations (supplemental Table 2). Because this subgroup analysis was not prespecified, and multiple subgroup analyses were performed, this incidental finding should be interpreted with great caution. Due to the low number of patients who had received bone marrow grafts in our study, we were not able to investigate the model in this subgroup. However, bone marrow grafts contain far lower numbers of NK cells than PBSC grafts, and no functional or clinical data exist that link special features of the NK repertoire of the bone marrow to NK-mediated alloreactivity or clinical outcomes.29,30 To summarize, we were not able to link the predicted impact of donor KIR3DL1/KIR2DS1 information to a certain procedure or patient selection. Due to the lack of independent validation studies for the reported effect, the hypothesis that the predicted impact can only be observed under conditions for the transplant procedure which trigger NK cell alloreactivity via KIR3DL1/KIR2DS1 can neither be supported nor ruled out. Finally, we did not observe a reduced incidence of acute GVHD in patients whose donors were KIR3DS1 positive (supplemental Figure 2), as was reported by Venstrom et al31 in 2010.

Extensive research on NK immunity has been conducted in chronic viral infections such as HIV or hepatitis C virus. Among sexual partners with one HIV-infected individual, KIR/KIR–ligand combinations that were compatible with the missing-self hypothesis affected the risk of virus transmission.16 Furthermore, protective KIR/KIR–ligand combinations were associated with a lower risk of HIV infection among sex workers.32 Moreover, distinct allelic combinations of the KIR3DL1 and HLA-B loci significantly and strongly influenced both AIDS progression and plasma HIV RNA abundance and spontaneous clearance of HCV.14,33 This justifies further scrutiny for an impact of KIR/KIR–ligand combinations also on tumor immunology and in the setting of allogeneic HCT. In contrast to changes introduced by viruses, however, loss or downregulation of HLA class I expression at the allelic level is infrequent on leukemic blasts at the time of diagnosis.11 Moreover, recent studies by independent groups suggest that tumor cells more often evade immune responses by downregulation of HLA class II expression, which might not trigger NK-cell activation.34,35 Further limitation for drawing parallels between KIR-mediated NK activity against virus-infected cells and tumor cells comes from the fact that viral peptides presented by HLA class I molecules may specifically alter the KIR/KIR–ligand binding.36,37 A strong peptide dependence of the KIR/KIR–ligand binding will make it very hard to predict KIR-mediated immune responses by donor cells.

Promising next steps comprise: (1) testing alternative hypothesis building on other KIR/KIR–ligand combinations or haplotype-based comparisons38 ; and (2) engaging in intergroup collaborations to settle the question of whether KIR-informed donor selection may improve outcome after allogeneic HCT. Follow-up studies with this goal are underway. Additional research should be conducted to understand the probable different contribution to NK-mediated alloreactivity of transfused mature NK cells vs of de novo produced NK cells that have matured and became educated in the host environment.13

In conclusion, this study shows that a donor selection model based on KIR2DS1/KIR3DL1 donor information does not universally predict relapse and mortality of patients with AML after matched unrelated donor HCT. Further research is warranted, to prove or disprove the impact of genetic markers, which promises to predict NK-mediated alloreactivity.

Data may be shared after request to the corresponding author by e-mail (Johannes Schetelig; e-mail, johannes.schetelig@uniklinikum-dresden.de).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the team of the Collaborative Biobank, especially Stephanie Maiwald, who coordinated the sample export and preanalytical processing; the DKMS Cord Blood bank; and the Scientific Team at DKMS Tübingen, who facilitated this analysis. They further acknowledge the excellent contribution of Bose Falk and Ute Solloch, who significantly contributed to the complex data management process. Finally, the authors are grateful to Kathy Hsu from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, who re-iterated the grouping of donors according to their KIR2DS1 and KIR3DL1 genotype and their cognate ligands to cross-check the classification.

Authorship

Contribution: J. Schetelig, H.B., F.H., S.W., A.H.S., and M.B. designed the trial; J. Schetelig, M.S., F.A.A., W.A.B., G.B., S.K., D.F., G.K., H.D.O., D.W.B., and M.B. contributed medical data; H.B., S.F., F.H., C.M., J. Sauter, S.W., and V.L. contributed to different levels of the processing of the genetic and medical data; J. Schetelig, S.F., H.B., and L.C.d.W. performed the statistical analysis; and J. Schetelig, F.H., and H.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors interpreted and discussed the results, and reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the German Cooperative Transplant Study Group appears in the supplemental appendix.

Correspondence: Johannes Schetelig, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, TU Dresden, Department of Internal Medicine I, Fetscherstr. 74, 01307 Dresden, Germany; e-mail: johannes.schetelig@uniklinikum-dresden.de.