In this issue of Blood, Navi et al report that the risk of arterial thromboembolic events (primarily stroke and myocardial infarction) increases substantially preceding a diagnosis of cancer by approximately 5 months and peaks during the month immediately before diagnosis when compared with patients who do not have and will not develop cancer. These findings potentially expand the current perception of Trousseau syndrome to also include arterial events.1

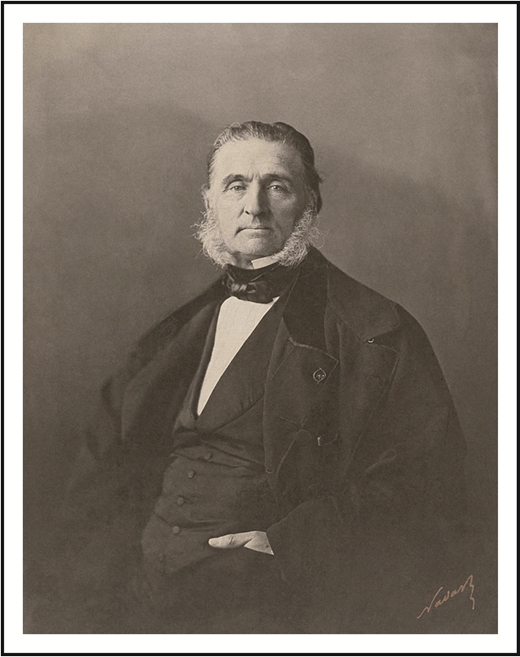

Portrait of Professor Armand Trousseau (1801-1867), French internist and politician, by Nadar. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57147969.

Portrait of Professor Armand Trousseau (1801-1867), French internist and politician, by Nadar. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57147969.

The association between cancer and clinical hypercoagulability is well-known to clinicians in 2 settings: the high prevalence and incidence of venous, visceral, and arterial thromboembolic events following a diagnosis of cancer and the concern for occult malignancy in patients diagnosed with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) (ie, preceding a diagnosis of cancer). The latter scenario is eponymously known as Trousseau syndrome after the eminent French physician, Professor Armand Trousseau (1801-1867) (see figure).2 In the 1860s, Trousseau published his famous text Clinique Medicale de l’Hotel‐Dieu, which included the lecture “Phlegmasia Alba Dolens,” a discussion and case series of patients who presented with thrombophlebitis or thrombosis and subsequently were diagnosed with malignancy.3 In an unfortunate turn of events, Professor Trousseau awoke on New Year’s Day in 1867 with an upper extremity phlebitis and reportedly conveyed his concerns to his student: “I am lost: the phlebitis that has just appeared tonight leaves me no doubt about the nature of my illness.”2 Indeed, he would die of a gastrointestinal cancer just a few months later, becoming both the diagnostician and patient of the eponymous Trousseau syndrome.

Since then, many investigators have focused on understanding the prevalence of occult malignancy in patients with unprovoked VTE. A systematic review reported a prevalence of previously undiagnosed cancer in patients with unprovoked VTE of 6.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.0%-7.1%) at baseline and 10.0% (95% CI, 8.6%-11.3%) from baseline to 12 months.4 However, hypercoagulability in cancer can manifest as both venous and arterial thromboembolism: Are arterial events associated with occult malignancy as well? To address this question, Navi and colleagues used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry and Medicare claims and investigated the risk of arterial thromboembolic events in the year preceding a diagnosis of cancer. They identified more than 370 000 pairs of cancer patients with common malignancies and control patients without cancer. Of these, 1.75% of cancer patients had an arterial event in the year preceding cancer diagnosis compared with 1.05% of controls (odds ratio, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.63-1.76). When evaluating 30-day intervals, which is possible given the large sample size of their cohort, the investigators found that rates increased progressively starting around 5 months and peaking in the month immediately before cancer diagnosis. These findings are consistent with previous case reports and cohort studies, but this study was conducted in a more comprehensive fashion with a well-matched cohort. Although a higher stage of cancer was associated with increased odds of arterial events, it is important to note that of patients with such events, stage 0 to 1 patients were roughly similar in proportion to stage 4 patients (28% and 24%, respectively).

What are the implications of this important study? First, these results add to the emerging consensus that arterial and venous thromboembolism are not quite as disparate as previously thought.5,6 Second, clinicians should recognize the possibility of occult malignancy in older patients diagnosed with stroke or myocardial infarction. They should ensure that age-appropriate screening is used and should not overreact by ordering imaging or other tests beyond age-appropriate screening. In patients with unprovoked venous events, such extensive screening strategies have not demonstrated survival benefit, and there are no data on any benefit in patients with arterial events.7 If Professor Trousseau presented with a stroke now, he would undergo screening colonoscopy but not necessarily a positron emission tomography (PET) scan. In this regard, less is still more.8 Finally, these findings highlight again that hypercoagulability often exists from the inception of malignancy and is not simply a preterminal complication of this illness. Despite a full century’s worth of clinical knowledge, however, we still do not have a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology of the hypercoagulable state of cancer, that is, why procoagulant proteins are upregulated so early in cancer development (even in some premalignant states) and why this is important for cancer progression and metastasis. Addressing this knowledge gap should be a priority for cancer biologists and translational researchers.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.A.K. received personal fees and/or nonfinancial support from Janssen, Bayer, Sanofi, Parexel, Halozyme, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Pharmacyclics, Pharmacyte, AngioDynamics, Leo Pharma, TriSalus, and Medscape and research grants to his institution from Merck, Array, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Leap Pharma.