Key Points

Donor T cells compete for IL-15 with NK cells during GVHD, resulting in profound defects in NK-cell reconstitution.

GVHD impairs NK-cell–dependent leukemia and pathogen-specific immunity.

Abstract

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (allo-BMT) is a curative therapy for hematological malignancies, but is associated with significant complications, principally graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and opportunistic infections. Natural killer (NK) cells mediate important innate immunity that provides a temporal bridge until the reconstruction of adaptive immunity. Here, we show that the development of GVHD after allo-BMT prevented NK-cell reconstitution, particularly within the maturing M1 and M2 NK-cell subsets in association with exaggerated activation, apoptosis, and autophagy. Donor T cells were critical in this process by limiting the availability of interleukin 15 (IL-15), and administration of IL-15/IL-15Rα or immune suppression with rapamycin could restore NK-cell reconstitution. Importantly, the NK-cell defect induced by GVHD resulted in the failure of NK-cell–dependent in vivo cytotoxicity and graft-versus-leukemia effects. Control of cytomegalovirus infection after allo-BMT was also impaired during GVHD. Thus, during GVHD, donor T cells compete with NK cells for IL-15 thereby inducing profound defects in NK-cell reconstitution that compromise both leukemia and pathogen-specific immunity.

Introduction

Although stem cell transplantation is an important therapy for hematological malignancies, the relatively high incidence of complications, namely graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD), disease relapse, and opportunistic infections, remains a challenge for improving mortality rates. GVHD occurs in 50% to 70% of patients and effects are commonly observed in the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and skin.1,2 GVHD is mediated by donor T cells and proinflammatory cytokines, however, the same cognate T-cell interactions also mediate curative graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effects.

Natural killer (NK) cells are present in most tissues; they originate from progenitors in the bone marrow (BM)3,4 and rely primarily on IL-15 to undergo differentiation.5 NK cells progress through 3 stages of differentiation: (1) immature CD27+CD11b−KLRG1− NK cells, which are most prevalent in the BM; (2) effector CD27+CD11b+KLRG1− M1 NK cells, which possess the highest level of cytokine production and cytolytic function; and (3) terminally differentiated CD27−CD11b+KLRG1+ M2 mature NK cells, which appear senescent.6,7 NK cells are capable of recognizing and killing virus-infected and malignant cells through simultaneous detection of altered major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I levels and a balance of activating and inhibitory signals.8,9 Activated NK cells can also potentiate immune responses through the rapid production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ).4,10 In view of these functions, NK cells have been considered a promising adjunct therapy for the treatment of leukemia, as well as cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation, because alloreactive NK cells do not appear to induce GVHD.11 As a result, numerous studies have investigated the therapeutic value of large doses of ex vivo–expanded NK cells to eradicate leukemia and prevent CMV reactivation with varying, but clear evidence of efficacy.12

Although the role of donor T cells and NK cells in controlling leukemia and CMV is well established, the interplays between these cells and how they affect their function after transplant remains unclear, especially in the context of GVHD. In this study, we demonstrate profound NK-cell defects during GVHD, mediated by donor T cells outcompeting NK cells for interleukin 15 (IL-15). We demonstrate that treatment with exogenous IL-15, or the immunosuppressive agent rapamycin, can rescue the NK-cell defects observed during GVHD. This study has implications for the protocols currently used to treat hematological malignancies, and highlights the need for considered approaches to immunotherapy that take into account the important interplays that occur between T and NK cells during GVHD.

Methods

Mice

Female (8-16 weeks) C57BL/6J (B6.WT, H-2b, CD45.2+), B6.CD45.1 (B6, H-2b, CD45.1+), B6D2F1 (H-2b/d), and BALB/c (H-2d) mice were from the Animal Resources Centre (Perth, WA, Australia). B6 IFNγR−/−, TNFRI/II−/−, IL-21R−/−, BALB/b (H-2Db), IFNαR−/−, NKp46cre+-Mcl1fl/fl, NKp46cre+-TGFRIIfl/fl, B6.CD11c-DOG were bred in-house. IL-15Rα−/− mice and controls were from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Procedures were performed with approval from the institutions’ animal ethics committees.

BM transplantation

Total-body irradiation was administered in 2 doses separated by 3 hours (137Cs source at 82 cGy per minute). B6, B6D2F1, and BALB/b mice received 1000, 1100, and 900 cGy, respectively. The next day, mice were injected IV with 5 × 106 whole or T-cell depleted (TCD) BM, with or without 1 × 106 (B6 and B6D2F1 recipients) or 3 × 106 (BALB/b recipients) T cells (80%-90% CD3+). TCD grafts containing 5 × 106 TCD BM only were transplanted as non-GVHD controls. For GVL transplants, 10 × 106 TCD BM, with or without 2-5 × 106 sorted CD8+ T cells were injected IV on day 0.

Assessment of GVHD

Mice were monitored daily and GVHD assessed as described.13 Mice with GVHD scores ≥6 were sacrificed and the date of death deemed as the next day.

Leukemia challenge

Recipients were injected IV on day 14 posttransplant with MLL-AF9-GFP+ tumor cells generated in B6-β2m−/− mice. Survival, clinical scores, and leukemia burdens in blood were determined via green fluorescent protein positive (GFP+).

Virus infection and quantitation

Mice were infected with MCMV-K181-Perth and organs collected at day 4 postinfection to determine viral titers, as described.14

IL-2 and IL-15 complexes

Each mouse received 200 μL of saline containing either 1.5 μg of recombinant murine IL-2 eBioscience) and 50 μg of anti-IL-2 (S4B6) or 0.5 μg of recombinant human IL-15 (Shenandoah Biotechnology) and 3 μg of recombinant murine IL-15Rα-Fc chimera (R&D Systems) on days described posttransplant.

Additional methods are included in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Results

Impaired donor NK-cell reconstitution in BMT recipients with GVHD

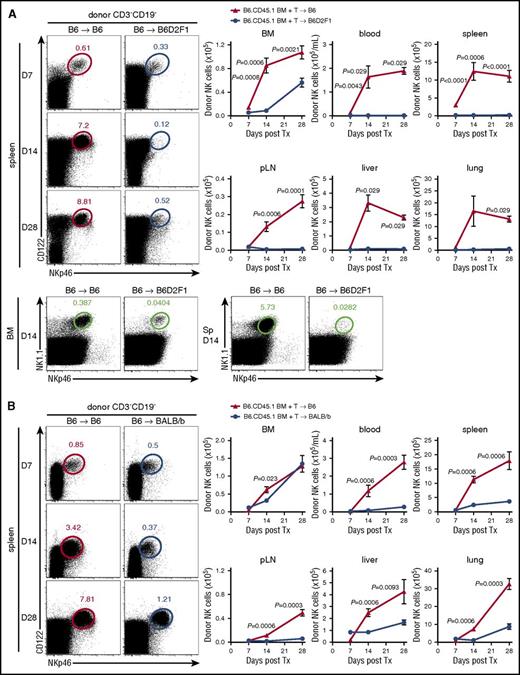

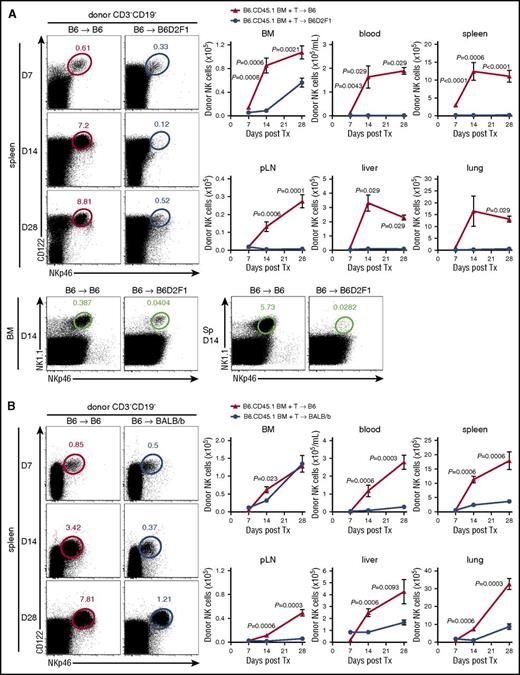

To understand the influence of alloreactive donor T cells on donor NK-cell reconstitution posttransplant, we used a BM transplantation (BMT) model where GVHD is directed against both MHC class I and II disparities (B6→B6D2F1) (supplemental Figure 1A). Donor NK cells (NKp46+CD122+CD3−CD19−) were examined in various organs posttransplant, comparing GVHD mice, which received an allogeneic transplant, with non-GVHD mice receiving a syngeneic (B6→B6) transplant. Significantly delayed reconstitution of donor (CD45.1+) NK cells was observed in the BM of mice with GVHD relative to BMT recipients without GVHD (Figure 1A), from day 7 onwards. This observation was even more striking in the blood, spleen, peripheral lymph nodes (pLNs), liver, and lung (Figure 1A), suggesting that in the presence of GVHD, donor NK cells fail to efficiently repopulate host tissues. Using congenic donor BM and T cells, we noted that NK cells derived predominantly from the BM (>80%). This profound NK defect was established by day 14, before GVHD-associated lymphopenia was evident and splenic hypertrophy was still present in mice with GVHD (spleen size, 120.1 ± 43.9 vs 59.7 ± 21.3 × 106 cells in GVHD vs non-GVHD controls). It should be noted that the defect in NK-cell reconstitution was confirmed by costaining donor NK cells with NKp46 and NK1.1, excluding NKp46 downregulation as being relevant (Figure 1A bottom).

NK-cell reconstitution is impaired in GVHD. (A) B6 (non-GVHD) and B6D2F1 (GVHD, MHC-mismatch) mice were transplanted with B6.CD45.1 BM and CD3+ T cells. Donor-derived CD3−CD19−NKp46+CD122+ NK cells were enumerated thereafter. Representative dot plots from the spleen at the time points indicated are shown. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) pooled from 2 or 3 independent experiments per time point for BM, spleen, pLNs. Data shows mean ± standard deviation (SD) from a single experiment per time point for blood, liver, and lung; n = 4-14 per group per time point. Representative plots of NKp46 and NK1.1 staining in the BM and spleen at day 14 posttransplant. (B) B6 (non-GVHD) and BALB/b (GVHD, MHC-matched, minor histocompatibility antigen-mismatched) mice were transplanted with B6.CD45.1 BM and CD3+ T cells and donor NK cells enumerated thereafter. Representative dot plots from the spleen at the time points indicated are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 1 or 2 independent experiments per time point for all tissues; n = 3-8 per group per time point. Tx, transplant.

NK-cell reconstitution is impaired in GVHD. (A) B6 (non-GVHD) and B6D2F1 (GVHD, MHC-mismatch) mice were transplanted with B6.CD45.1 BM and CD3+ T cells. Donor-derived CD3−CD19−NKp46+CD122+ NK cells were enumerated thereafter. Representative dot plots from the spleen at the time points indicated are shown. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) pooled from 2 or 3 independent experiments per time point for BM, spleen, pLNs. Data shows mean ± standard deviation (SD) from a single experiment per time point for blood, liver, and lung; n = 4-14 per group per time point. Representative plots of NKp46 and NK1.1 staining in the BM and spleen at day 14 posttransplant. (B) B6 (non-GVHD) and BALB/b (GVHD, MHC-matched, minor histocompatibility antigen-mismatched) mice were transplanted with B6.CD45.1 BM and CD3+ T cells and donor NK cells enumerated thereafter. Representative dot plots from the spleen at the time points indicated are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 1 or 2 independent experiments per time point for all tissues; n = 3-8 per group per time point. Tx, transplant.

NK-cell reconstitution was then examined in a MHC-matched system in which GVHD (supplemental Figure 1B) is induced against multiple minor histocompatibility antigens (B6→BALB/b). In this system, NK-cell reconstitution in the BM was only transiently reduced (Figure 1B). However, NK-cell numbers in the blood, spleen, pLNs, liver, and lung of GVHD mice were again significantly diminished (Figure 1B), consistent with a broad defect in donor NK-cell reconstitution in the presence of GVHD.

Using CD27 and CD11b, 4 stages of NK-cell development and differentiation can be identified and further refined using KLRG1 and CD43 expression.6,7 Immature and M1 NK cells, identified as CD27+CD11b−CD43+KLRG1− (herein iNK) and CD27+CD11b+CD43+KLRG1− (herein M1), respectively, were significantly reduced in number in the BM of major MHC-mismatched mice with GVHD at days 14 and 28 posttransplant, compared with their non-GVHD counterparts (Figure 2A). In the second BMT model, numbers of donor iNK and M1 NK cells in the BM of mice with GVHD were similar to those in non-GVHD mice (Figure 2B), suggesting that GVHD predominantly affects NK-cell differentiation in the periphery. Consistent with this, M1 and M2 NK cells were significantly reduced in the spleen of mice with GVHD (Figure 2C). Together, these data indicate that during GVHD, donor NK-cell development is impaired, predominantly in the periphery due to a defect in donor NK-cell differentiation that occurs after the iNK-cell stage.

NK-cell subset reconstitution and activation during GVHD. (A) Donor NK-cell subsets (CD27+CD11b−CD43+KLRG1− [iNK], CD27+CD11b+CD43+KLRG1− [M1 NK], CD11b+CD27−CD43+KLRG1+ [M2 NK]) were examined, as indicated, in BM in the B6→B6D2F1 system. Representative dot plots from the BM at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 or 3 independent experiments per time point; n = 8 – 12 per group per time point. (B) Donor NK-cell subsets were examined in the BM in the B6→BALB/b system. Representative dot plots from the BM at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 7-8 per group per time point. (C) Quantitation of donor-derived splenic NK-cell subsets (B6→BALB/b). Mean ± SEM pooled from 1 (day 7) or 2 (day 14 and day 28) independent experiments per time point; n = 3-8 per group per time point. (D) CD69 expression by donor NK cells in the BM, spleen, liver, and lung was assessed at day 7, day 14, and day 28 in the B6→BALB/b model. Representative histograms are shown from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 3-8 per group per time point.

NK-cell subset reconstitution and activation during GVHD. (A) Donor NK-cell subsets (CD27+CD11b−CD43+KLRG1− [iNK], CD27+CD11b+CD43+KLRG1− [M1 NK], CD11b+CD27−CD43+KLRG1+ [M2 NK]) were examined, as indicated, in BM in the B6→B6D2F1 system. Representative dot plots from the BM at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 or 3 independent experiments per time point; n = 8 – 12 per group per time point. (B) Donor NK-cell subsets were examined in the BM in the B6→BALB/b system. Representative dot plots from the BM at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 7-8 per group per time point. (C) Quantitation of donor-derived splenic NK-cell subsets (B6→BALB/b). Mean ± SEM pooled from 1 (day 7) or 2 (day 14 and day 28) independent experiments per time point; n = 3-8 per group per time point. (D) CD69 expression by donor NK cells in the BM, spleen, liver, and lung was assessed at day 7, day 14, and day 28 in the B6→BALB/b model. Representative histograms are shown from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 3-8 per group per time point.

Donor NK cells are activated during GVHD

GVHD results in a characteristic cytokine storm early after BMT that likely influences innate immunity.15,16 In mice with GVHD, early after BMT (day 7), donor NK cells in all tissues expressed increased levels of CD69 relative to donor NK cells in syngeneic BMT recipients (Figure 2D). By days 14 and 28 posttransplant the overall expression level of CD69 had decreased, but was still higher in NK cells within the liver and lung of mice with GVHD (Figure 2D). Thus, donor NK cells are activated within target tissues during GVHD.

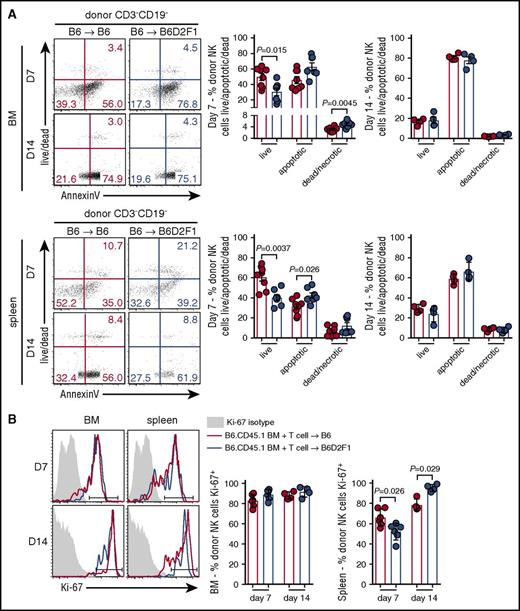

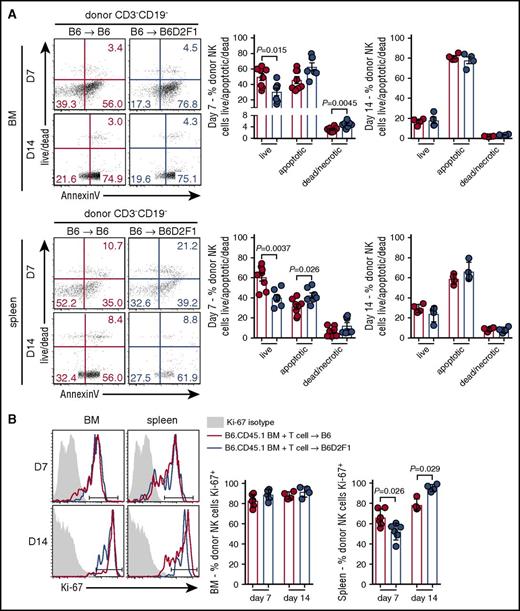

Having established that the presence of GVHD impairs donor NK-cell reconstitution, concomitantly with increased activation, we examined whether these defects were associated with changes in apoptosis and/or proliferation. At day 7 posttransplant, donor NK cells in the BM of mice with GVHD exhibited significantly reduced proportions of live cells and increased frequencies of necrotic cells. Significantly reduced proportions of live donor NK cells were also observed in the spleen of GVHD mice, together with significantly increased frequencies of apoptotic cells (Figure 3A). No difference was noted between the groups in either the BM or splenic NK cells at day 14 posttransplant (Figure 3A). In addition, NK-cell proliferation, as assessed by Ki67, was equivalent in BM donor NK cells in GVHD and non-GVHD mice (Figure 3B). In contrast, in the spleen at day 7, we observed a small but significant reduction in donor NK-cell proliferation in mice with GVHD, which was reversed at day 14 (Figure 3B). Together, these data indicate that during GVHD, poor NK-cell reconstitution in the BM and spleen is due to enhanced apoptosis with an early defect in proliferation of donor NK cells also observed in the spleen.

Increased apoptosis of splenic donor NK cells during the early phase of GVHD. (A) Donor NK cells in the BM (top) and spleen (bottom) at day 7 and day 14 posttransplant (B6→B6D2F1) were stained with Sytox Blue and Annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry to quantify live cells (live/dead−Annexin V−), apoptotic cells (live/dead−Annexin V+), and dead/necrotic cells (live/dead+Annexin V+). Representative dot plots from the BM and spleen at the time points indicated are shown. Day 7 mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 7-8 per group. Day 14 mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 4 per group. (B) Ki-67 expression by donor NK cells in the BM and spleen (B6→B6D2F1). Representative histograms shown with the same isotype control (shaded histogram) shown for day 7 and day 14. Mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 4-6 per group per time point.

Increased apoptosis of splenic donor NK cells during the early phase of GVHD. (A) Donor NK cells in the BM (top) and spleen (bottom) at day 7 and day 14 posttransplant (B6→B6D2F1) were stained with Sytox Blue and Annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry to quantify live cells (live/dead−Annexin V−), apoptotic cells (live/dead−Annexin V+), and dead/necrotic cells (live/dead+Annexin V+). Representative dot plots from the BM and spleen at the time points indicated are shown. Day 7 mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 7-8 per group. Day 14 mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 4 per group. (B) Ki-67 expression by donor NK cells in the BM and spleen (B6→B6D2F1). Representative histograms shown with the same isotype control (shaded histogram) shown for day 7 and day 14. Mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 4-6 per group per time point.

GVHD induced by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells impairs NK-cell reconstitution

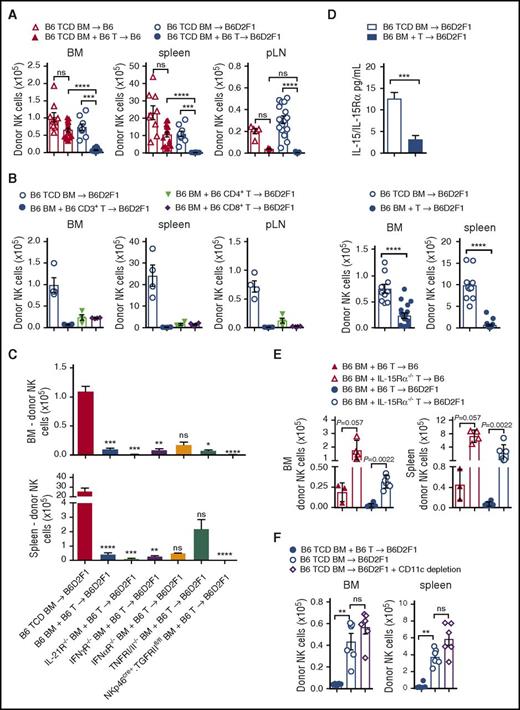

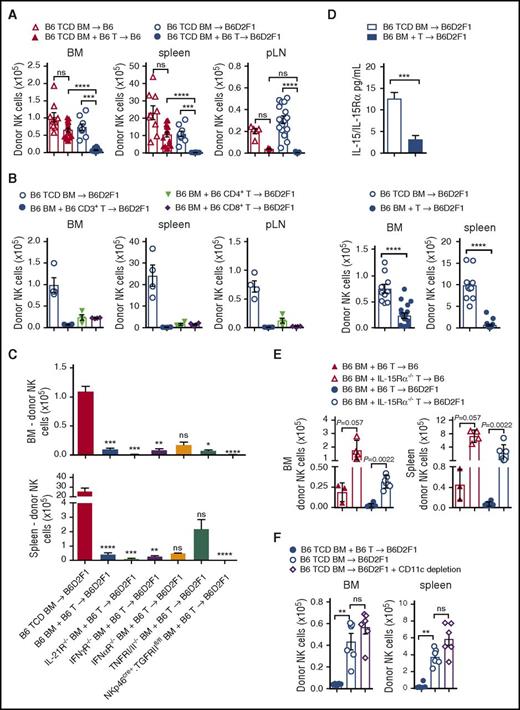

During lymphocyte reconstitution, extensive homeostatic expansion occurs due to the lymphopenic environment induced by conditioning, in addition to responses to alloantigen. Cell lineages with similar growth factor requirements can thus compete with each other during this time. To determine whether donor T cells were involved in the poor NK-cell reconstitution, we performed transplants with TCD grafts in syngeneic and allogeneic settings and compared these with T-cell replete grafts. As expected, we noted significant reductions in donor NK-cell numbers with T-cell replete allogeneic grafts, compared with T-cell replete syngeneic grafts (Figure 4A). Higher NK-cell numbers were also observed in syngeneic transplants that did not receive T cells, consistent with an inhibitory interplay occurring between donor T and NK cells even in the absence of GVHD (Figure 4A).

Donor T cells competing for IL-15 signaling impairs NK-cell reconstitution. (A) B6 and B6D2F1 recipients were transplanted with B6.CD45.1+ BM and CD3+ T cells or TCD BM and donor NK cells were quantified at day 14. BM and spleen data show mean ± SEM pooled from 2 to 4 independent experiments; n = 9-18 per group. pLN data show mean ± SEM pooled from 1 to 5 independent experiments; n = 4-23 per group. (B) B6D2F1 recipients were transplanted with 5 × 106 B6.BM and 1 × 106 B6.CD3+ T cells or 0.5 × 106 sorted B6.CD4+ or 0.5 × 106 sorted B6.CD8+ T cells or B6.TCD BM. Donor NK cells were quantified at day 14. Mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 4 per group. (C) B6D2F1 recipients received B6.TCD BM, B6.BM or IL-21R−/−, IFNγR−/−, IFNαR−/−, TNFRI/II−/−, or NKp46cre+.TGFRIIfl/fl BM together with B6.CD3+ T cells and BM and spleen NK cells were quantified at day 14. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 to 5 experiments for B6 TCD, B6 BM + T-cell and IFNγR−/− TCD BM groups; n = 8-20. Mean ± SD from a single experiment for remaining groups; n = 2-5 per group. (D) Quantitation of serum IL-15/IL-15R complex levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) at day 14 posttransplant. Enumeration of respective donor NK-cell numbers in BM and spleen is shown. Mean ± SEM, pooled from 3 to 5 experiments; n = 10-18 per group. (E) Recipients were transplanted with B6 BM and either B6.CD3+ T cells or IL-15Rα−/−.CD3+ T cells. BM and T cells for these experiments originated in the United States, hence the reduced overall cell numbers. Donor NK cells were enumerated in the BM and spleen at day 18 posttransplant. Mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 3-6 per group. (F) B6D2F1 recipients were transplanted with donor grafts containing either B6 TCD BM with B6.CD3+ T cells, B6 TCD BM alone, or B6.CD11c-DOG TCD BM alone. CD11c+ cells were depleted with diphtheria toxin (DT) administered from day 5 post-SCT (160 ng per dose per mouse) and then every 2 days thereafter. NK cells were enumerated in BM and spleen on day 14. Mean ± SEM from 1 experiment is shown; n = 6 per group. Kruskall-Wallis test with the Dunn multiple comparisons correction was performed in panels A through C. Comparisons were made with the TCD BM group in panel C. The Mann-Whitney test was performed in panels D, E, and F.

Donor T cells competing for IL-15 signaling impairs NK-cell reconstitution. (A) B6 and B6D2F1 recipients were transplanted with B6.CD45.1+ BM and CD3+ T cells or TCD BM and donor NK cells were quantified at day 14. BM and spleen data show mean ± SEM pooled from 2 to 4 independent experiments; n = 9-18 per group. pLN data show mean ± SEM pooled from 1 to 5 independent experiments; n = 4-23 per group. (B) B6D2F1 recipients were transplanted with 5 × 106 B6.BM and 1 × 106 B6.CD3+ T cells or 0.5 × 106 sorted B6.CD4+ or 0.5 × 106 sorted B6.CD8+ T cells or B6.TCD BM. Donor NK cells were quantified at day 14. Mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 4 per group. (C) B6D2F1 recipients received B6.TCD BM, B6.BM or IL-21R−/−, IFNγR−/−, IFNαR−/−, TNFRI/II−/−, or NKp46cre+.TGFRIIfl/fl BM together with B6.CD3+ T cells and BM and spleen NK cells were quantified at day 14. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 to 5 experiments for B6 TCD, B6 BM + T-cell and IFNγR−/− TCD BM groups; n = 8-20. Mean ± SD from a single experiment for remaining groups; n = 2-5 per group. (D) Quantitation of serum IL-15/IL-15R complex levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) at day 14 posttransplant. Enumeration of respective donor NK-cell numbers in BM and spleen is shown. Mean ± SEM, pooled from 3 to 5 experiments; n = 10-18 per group. (E) Recipients were transplanted with B6 BM and either B6.CD3+ T cells or IL-15Rα−/−.CD3+ T cells. BM and T cells for these experiments originated in the United States, hence the reduced overall cell numbers. Donor NK cells were enumerated in the BM and spleen at day 18 posttransplant. Mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 3-6 per group. (F) B6D2F1 recipients were transplanted with donor grafts containing either B6 TCD BM with B6.CD3+ T cells, B6 TCD BM alone, or B6.CD11c-DOG TCD BM alone. CD11c+ cells were depleted with diphtheria toxin (DT) administered from day 5 post-SCT (160 ng per dose per mouse) and then every 2 days thereafter. NK cells were enumerated in BM and spleen on day 14. Mean ± SEM from 1 experiment is shown; n = 6 per group. Kruskall-Wallis test with the Dunn multiple comparisons correction was performed in panels A through C. Comparisons were made with the TCD BM group in panel C. The Mann-Whitney test was performed in panels D, E, and F.

To further define whether donor CD4+, CD8+, or both T-cell subsets were mediating this effect during GVHD, we sorted CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, and transplanted them into allogeneic recipients in equivalent numbers to those found in our whole CD3+ T-cell preparation, and quantified NK-cell numbers at day 14 posttransplant. Analysis of the BM, spleen, and pLNs revealed that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells impaired donor NK-cell reconstitution to a similar extent as grafts containing both T-cell subsets (Figure 4B). These data suggest that donor T cells compete with NK cells, and that this is not restricted to a single T-cell subset.

IL-15 consumption by donor T cells impairs NK-cell reconstitution

In order to define the factors that donor T cells might be providing or consuming to abrogate donor NK-cell expansion, we performed a series of allogeneic transplants with grafts containing relevant cytokine or cytokine receptor deficiencies. In some settings, IL-21 has been shown to inhibit NK-cell expansion,17-19 therefore we transplanted IL-21R−/− BM together with wild-type (WT) T cells into lethally irradiated recipients and quantified donor NK-cell numbers. Like recipients receiving WT T-cell replete grafts, IL-21R−/− grafts failed to generate NK cells in the BM and spleen (Figure 4C). Similarly, BM lacking expression of the IFN-γ, IFN-α, or tumor necrosis factor I/II (TNFI/II) receptors failed to restore donor NK-cell numbers to those observed in non-GVHD controls (Figure 4C). Furthermore, specific deletion of the transforming growth factor βRII (TGFβRII) in NK cells, to preclude the TGFβ-mediated signaling that is known to impair NK-cell function,20 failed to improve NK-cell reconstitution (Figure 4C).

IL-15 is crucial for NK-cell survival and proliferation; CD8 T cells also have strict requirements for IL-15.21 To investigate whether IL-15 consumption by donor T cells was responsible for the NK-cell defect during GVHD, we analyzed levels of IL-15/IL-15R complexes in the serum. Allogeneic recipients of TCD grafts had high levels of IL-15/IL-15R complexes, whereas GVHD mice presented with significantly lower levels which correlated with reduced NK-cell numbers (Figure 4D). To determine whether IL-15 consumption by T cells is responsible for the NK-cell defect, we transplanted recipients with WT BM and WT T cells or WT BM and IL-15Rα−/− T cells in both non-GVHD and GVHD settings. NK-cell reconstitution was significantly improved in recipients of IL-15Rα−/− T cells, compared with those that received WT T cells, with effects seen in both GVHD and non-GVHD groups (Figure 4E). These data demonstrate that donor T cells out competed NK cells for IL-15 after BMT, impairing NK-cell reconstitution. Because donor dendritic cells may be an important source of IL-15 after BMT, we deleted them after BMT as previously described.22 We undertook these experiments in syngeneic recipients because NK cells were already absent in GVHD animals, making quantification of further reductions difficult. Importantly, dendritic cell depletion had no effect on NK-cell numbers (Figure 4F).

Exogenous IL-15 or immunosuppression restores NK-cell reconstitution

Having established that IL-15 consumption by donor T cells impairs NK-cell reconstitution, we investigated whether this effect could be overcome by providing exogenous IL-15. GVHD-affected mice were treated with 2 doses of IL-15–IL-15Rα complexes, which more effectively stimulate cell expansion than IL-15 alone and replicate the trans-presentation of IL-15 that occurs in vivo.5,23 The provision of supraphysiological levels of IL-15 is likely to expand both NK progenitors as well as known effects on mature NK cells.24 Indeed, administration of IL-15 complexes significantly increased NK-cell numbers in the BM, spleen, and pLNs (Figure 5A).

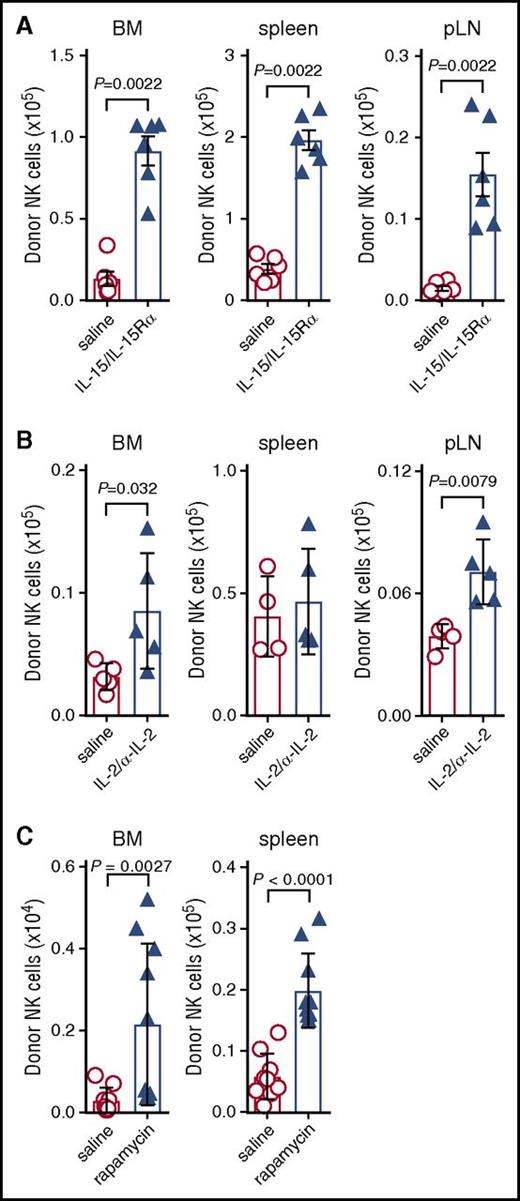

Exogenous IL-15 administration restores donor NK-cell reconstitution during GVHD. (A) B6D2F1 recipients were transplanted with B6 BM and CD3+ T cells and treated with saline (red) or IL-15/IL-15Rα complexes (blue). On day 7 posttransplant, donor-derived NK cells in the BM, spleen, and pLNs were quantified. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 6 per group. (B) Mice transplanted as in panel A were treated with IL-2/anti-IL-2 S4B6 complex. Donor NK-cell numbers were quantified on day 7. Mean ± SD from 1 of 2 independent experiments; n = 4-5 per group. (C) Mice were transplanted as in panel A, but received daily doses of saline or rapamycin (600 μg/kg; Wyeth) intraperitoneally daily for 9 days. Donor NK cells in the BM and spleen were enumerated at day 10 posttransplant. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 9-10 per group. Mann-Whitney tests were performed in panels A-C.

Exogenous IL-15 administration restores donor NK-cell reconstitution during GVHD. (A) B6D2F1 recipients were transplanted with B6 BM and CD3+ T cells and treated with saline (red) or IL-15/IL-15Rα complexes (blue). On day 7 posttransplant, donor-derived NK cells in the BM, spleen, and pLNs were quantified. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 6 per group. (B) Mice transplanted as in panel A were treated with IL-2/anti-IL-2 S4B6 complex. Donor NK-cell numbers were quantified on day 7. Mean ± SD from 1 of 2 independent experiments; n = 4-5 per group. (C) Mice were transplanted as in panel A, but received daily doses of saline or rapamycin (600 μg/kg; Wyeth) intraperitoneally daily for 9 days. Donor NK cells in the BM and spleen were enumerated at day 10 posttransplant. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 9-10 per group. Mann-Whitney tests were performed in panels A-C.

IL-2 is also noted for its ability to stimulate T- and NK-cell activation and proliferation. Thus, GVHD mice were treated with IL-2 complexed with the anti-IL-2 antibody S4B6 and donor NK cells enumerated. IL-2 complexes mediated a significant but very minor expansion of donor NK cells (Figure 5B), consistent with the notion that IL-15 consumption is the primary mechanism for failure of NK-cell reconstitution during GVHD.

Immune suppression is routinely used clinically to reduce donor T-cell proliferation and effector function, and thus GVHD. We hypothesized that the NK-cell defect seen during GVHD would be improved by treating mice with the immunosuppressive drug rapamycin through reducing donor T-cell activation25,26 and their consumption of IL-15. BMT recipients were thus treated daily for 9 days and on day 10 posttransplant NK-cell numbers were quantified. Treatment with rapamycin significantly increased NK-cell numbers in the BM and spleen compared with saline control (Figure 5C), while reducing T-cell expansion (2.8 ± 0.3 vs 3.9 ± 0.3 × 105 per femur; P = .02) and GVHD severity (clinical score, 3.3 ± 0.3 vs 4.6 ± 0.1; P = .02). Taken together, these data indicated that poor NK-cell reconstitution could be improved by treatment with exogenous IL-15 or T-cell targeted immune suppression.

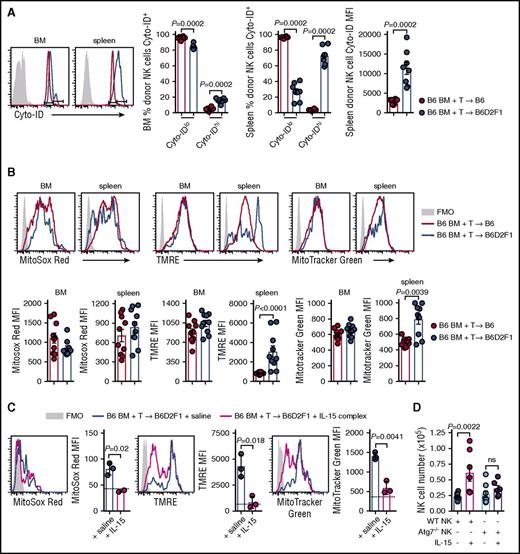

GVHD results in autophagy and mitophagy in NK cells

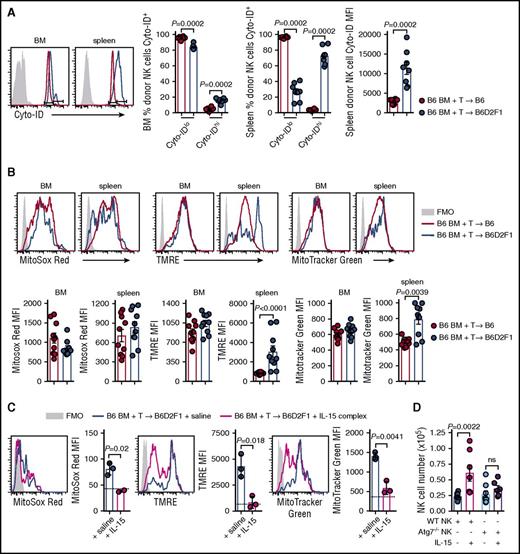

Autophagy is a process of cytosolic protein degradation and recycling that promotes cellular survival at times of cellular stress, particularly during cytokine starvation.27 To understand the effect of IL-15 starvation on autophagy in NK cells during GVHD, we stained donor NK cells from the BM and spleen with Cyto-ID which labels vesicles generated during autophagy. At day 14 posttransplant, the frequency of BM-isolated donor NK cells expressing high levels of Cyto-ID was significantly increased in mice with GVHD (Figure 6A). These differences were more obvious in the spleen where a dramatic decrease and increase in Cyto-IDlo and Cyto-IDhi donor NK cells, respectively, were observed during GVHD (Figure 6A). This is consistent with a significant increase in the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Cyto-ID in donor NK cells (Figure 6A). Autophagy of dysfunctional/damaged mitochondria, termed mitophagy, is a process that occurs in memory NK cells to promote their survival.28 We used 3 cellular stains to interrogate donor NK-cell mitochondrial quality postallogeneic transplant. At day 14, donor NK cells in non-GVHD and GVHD mice expressed equivalent levels of MitoSox Red (measuring mitochondrial-associated reactive oxygen species) in the BM and spleen (Figure 6B left). The MFI for tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester, perchlorate (TMRE; measuring mitochondrial membrane potential) was significantly higher in splenic NK cells, but not BM-derived NK cells, in GVHD compared with non-GVHD mice (Figure 6B center). No difference in MitoTracker Green MFI (measuring mitochondrial density) was observed in donor NK cells from the BM, however, this was significantly increased in the spleen of mice with GVHD (Figure 6B right). Next, we examined the effect of IL-15 rescue on mitochondrial stress during GVHD. The levels of MitoSox Red, TMRE, and MitoTracker Green in donor NK cells from the BM decreased in IL-15 complex treated recipients, down to levels seen in nontransplanted mice (Figure 6C). To establish whether the NK-cell expansion induced by IL-15 administration was autophagy dependent, we performed allogeneic transplants with either NKp46cre+.Atg7WT/WT BM or NKp46cre+.Atg7fl/fl BM. In this system, NK cells derived from the BM of NKp46cre+.Atg7fl/fl are specifically unable to use the autophagy pathway. We enumerated donor NK cells in the BM at day 14 posttransplant and observed that IL-15 complex treatment could not rescue NK-cell numbers if the NK cells lacked Atg7 (Figure 6D). Together, these data show that GVHD induces autophagy and mitophagy in donor NK cells when IL-15 is limiting. Exogenous IL-15 leads to NK-cell expansion that requires autophagy in order to ameloriate mitochondrial stress. This is consistent with the notion that the autophagy induced by GVHD is the result of IL-15 starvation.

Autophagy and mitophagy are enhanced during GVHD. (A) B6 and B6D2F1 mice were transplanted with B6.CD45.1 BM and CD3+ T cells. The frequency of Cyto-ID+ NK cells in the BM and spleen and the Cyto-ID MFI in the spleen of donor NK cells was quantified. Representative histograms at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 8 per group. (B) Levels of MitoSox Red, MitoTracker Green, and TMRE were examined in the donor NK cells from the mice in panel A. MFI values for the 3 mitophagy stains were quantified. Representative histograms at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 10 per group. (C) B6.BM and B6.CD3+ T cells was transplanted into lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipients and treated on day 7 and day 10 with saline or IL-15 complex. Quantitation of MitoSox Red, TMRE, and MitoTracker Green levels in donor NK cells from the BM at day 14. Dotted line indicates level in a nontransplanted B6 mouse. Mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 3 per group. (D) Enumeration of donor NK cells in the BM at day 14 posttransplant after BM from B6.NKp46cre+.Atg7WT/WT or B6.NKp46cre+.Atg7fl/fl was transplanted together with B6.CD3+ T cells into lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipients and treated as in panel C. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 6-8 per group. Mann-Whitney tests were performed in panels A and B. The unpaired t test with Welch correction was performed in panels C and D. FMO, fluorescence minus one.

Autophagy and mitophagy are enhanced during GVHD. (A) B6 and B6D2F1 mice were transplanted with B6.CD45.1 BM and CD3+ T cells. The frequency of Cyto-ID+ NK cells in the BM and spleen and the Cyto-ID MFI in the spleen of donor NK cells was quantified. Representative histograms at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 8 per group. (B) Levels of MitoSox Red, MitoTracker Green, and TMRE were examined in the donor NK cells from the mice in panel A. MFI values for the 3 mitophagy stains were quantified. Representative histograms at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 10 per group. (C) B6.BM and B6.CD3+ T cells was transplanted into lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipients and treated on day 7 and day 10 with saline or IL-15 complex. Quantitation of MitoSox Red, TMRE, and MitoTracker Green levels in donor NK cells from the BM at day 14. Dotted line indicates level in a nontransplanted B6 mouse. Mean ± SD from 1 experiment; n = 3 per group. (D) Enumeration of donor NK cells in the BM at day 14 posttransplant after BM from B6.NKp46cre+.Atg7WT/WT or B6.NKp46cre+.Atg7fl/fl was transplanted together with B6.CD3+ T cells into lethally irradiated B6D2F1 recipients and treated as in panel C. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 6-8 per group. Mann-Whitney tests were performed in panels A and B. The unpaired t test with Welch correction was performed in panels C and D. FMO, fluorescence minus one.

GVHD-induced NK-cell defects compromise both leukemia and virus-specific immunity

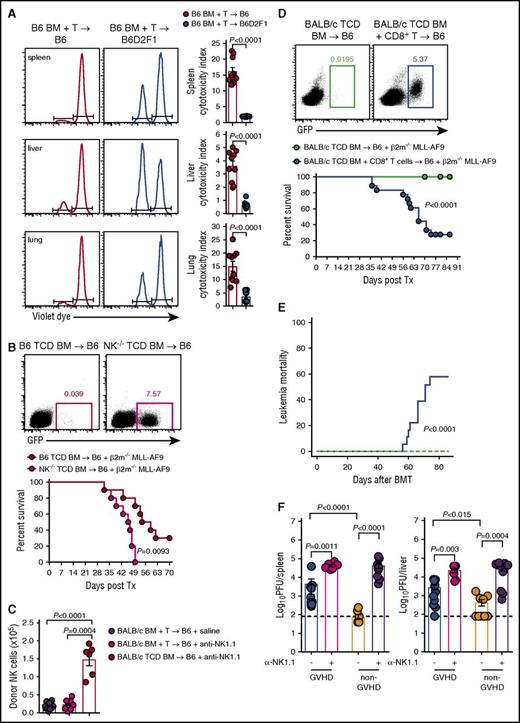

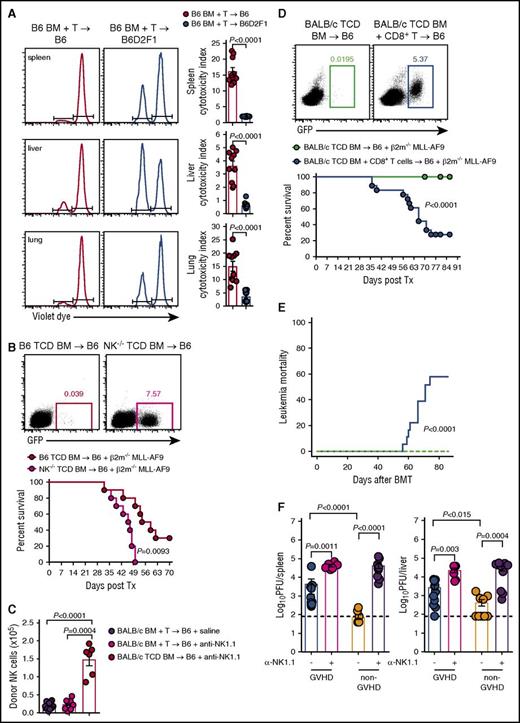

Having established that GVHD results in profound NK-cell defects via competition for IL-15 by donor T cells, we hypothesized that this defect would impact the control of leukemia and CMV infection. First, we examined the cytotoxic capacity of NK cells by labeling RMA (NK resistant) and RMA-S (NK sensitive) cell lines with high and low doses of violet proliferation dye, respectively, mixing them in a 1:1 ratio and injecting them into GVHD and non-GVHD mice at day 14 posttransplant. We then analyzed clearance of these tumor cell lines in vivo. RMA-S cells were eliminated less effectively from the spleen, liver, and lung of mice with GVHD compared with non-GVHD controls, as determined by cytotoxicity indexes (Figure 7A). Next, we developed a primary tumor deficient in β2m through transduction of the common acute myeloid leukemia (AML) translocation MLL-AF9 into β2m−/− stem cells, which were then propagated in vivo. The resulting MLL-AF9 AML expresses GFP, enabling tracking of tumor growth through serial bleeds. We initially demonstrated that β2m−/− MLL-AF9 AML was NK-cell sensitive by transplanting this leukemia, together with either WT TCD BM or TCD BM from NKp46Cre+.Mcl1fl/fl mice (which lack NK cells and hereafter referred to as NK−/−).29 Mice that received BM deficient in NK cells showed significantly impaired survival and increased proportions of MLL-AF9 AML in the blood from days 21 to 49 posttransplant (Figure 7B). The BALB/c→B6 model which also showed impaired donor NK-cell reconstitution during GVHD demonstrated that this was not altered by the specific deletion of recipient NK cells (Figure 7C), excluding this population as a major competing source for IL-15 after BMT. Importantly, when β2m−/− MLL-AF9 AML was transplanted into mice with GVHD (induced by CD8 T cells) and thus NK-cell deficient, or mice without GVHD and NK-cell replete, the former succumbed to leukemia with detectable circulating GFP+ AML cells (Figure 7D). This marked reduction in overall survival in animals with GVHD (and NK deficiency) was primarily due to high levels of mortality from this NK-sensitive leukemia (Figure 7E), confirming impaired NK-dependent GVL during GVHD.

Failure to reconstitute NK-cell during GVHD impairs GVL and CMV responses. (A) B6.BM and CD3+ T cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated B6 or B6D2F1 recipients. At day 14 posttransplant, 20 × 106 NK-resistant RMA cells and 20 × 106 NK-sensitive RMA-S cells labeled with high and low concentrations of violet proliferation dye, respectively, were injected IV. Sixteen hours later, the ratio of RMA:RMA-S was quantified to determine the cytotoxic capacity of NK cells in the spleen, liver, and lung. Representative histograms are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 10 per group. (B) Lethally irradiated B6 mice received either B6.TCD BM or TCD B6.NKp46cre+.Mcl1fl/fl BM together with 104 GFP+ β2m−/− MLL-AF9 AML cells and monitored for survival. Representative dot plots of peripheral blood day 42 post-MLL-AF9 injection are shown. Kaplan-Meier overall survival plot from 2 independent experiments is shown; n = 10 per group. (C) Lethally irradiated B6 mice were treated with saline or anti-NK1.1 and transplanted with TCD BALB/c.BM ± T cells. Donor NKp46+CD122+ NK cells were enumerated at day 7; n = 9-15 in T-cell replete and n = 6 in TCD groups from 2 combined experiments. (D-E) Lethally irradiated B6 mice received either TCD BALB/c.BM with or without sorted BALB/c CD8+ T cells. At day 14 posttransplant, 2 × 105 GFP+ β2m−/− MLL-AF9 AML cells were transferred and survival was monitored. Representative dot plots of peripheral blood from day 49 post-MLL-AF9 injection are shown. (D) Kaplan-Meier overall survival plot and (E) leukemia mortality by competing risk analysis from 3 independent experiments is shown; n = 18 per group. (F) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were transplanted with either B6.BM and CD4+ T cells (GVHD group) or B6.TCD BM alone (non-GVHD group), allowed to engraft for 21 days, then infected with MCMV. Two additional GVHD and non-GVHD groups received anti-NK1.1 antibody prior to and during MCMV infection (day −2, 0, and +2). Viral loads, measured as plaque-forming units (PFU), in the spleen and liver were determined 4 days later. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 6-11 per group. Mann-Whitney tests performed in panels A, C, and F. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was performed for the survival data in panels B and D. Incidence of leukemia mortality in panel E was performed by competing risk analysis using R software.

Failure to reconstitute NK-cell during GVHD impairs GVL and CMV responses. (A) B6.BM and CD3+ T cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated B6 or B6D2F1 recipients. At day 14 posttransplant, 20 × 106 NK-resistant RMA cells and 20 × 106 NK-sensitive RMA-S cells labeled with high and low concentrations of violet proliferation dye, respectively, were injected IV. Sixteen hours later, the ratio of RMA:RMA-S was quantified to determine the cytotoxic capacity of NK cells in the spleen, liver, and lung. Representative histograms are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 10 per group. (B) Lethally irradiated B6 mice received either B6.TCD BM or TCD B6.NKp46cre+.Mcl1fl/fl BM together with 104 GFP+ β2m−/− MLL-AF9 AML cells and monitored for survival. Representative dot plots of peripheral blood day 42 post-MLL-AF9 injection are shown. Kaplan-Meier overall survival plot from 2 independent experiments is shown; n = 10 per group. (C) Lethally irradiated B6 mice were treated with saline or anti-NK1.1 and transplanted with TCD BALB/c.BM ± T cells. Donor NKp46+CD122+ NK cells were enumerated at day 7; n = 9-15 in T-cell replete and n = 6 in TCD groups from 2 combined experiments. (D-E) Lethally irradiated B6 mice received either TCD BALB/c.BM with or without sorted BALB/c CD8+ T cells. At day 14 posttransplant, 2 × 105 GFP+ β2m−/− MLL-AF9 AML cells were transferred and survival was monitored. Representative dot plots of peripheral blood from day 49 post-MLL-AF9 injection are shown. (D) Kaplan-Meier overall survival plot and (E) leukemia mortality by competing risk analysis from 3 independent experiments is shown; n = 18 per group. (F) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were transplanted with either B6.BM and CD4+ T cells (GVHD group) or B6.TCD BM alone (non-GVHD group), allowed to engraft for 21 days, then infected with MCMV. Two additional GVHD and non-GVHD groups received anti-NK1.1 antibody prior to and during MCMV infection (day −2, 0, and +2). Viral loads, measured as plaque-forming units (PFU), in the spleen and liver were determined 4 days later. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments; n = 6-11 per group. Mann-Whitney tests performed in panels A, C, and F. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was performed for the survival data in panels B and D. Incidence of leukemia mortality in panel E was performed by competing risk analysis using R software.

CMV is a significant opportunistic infection following allo-BMT, as patients are lymphopenic and NK cells are important in controlling the virus during this time. Thus, we compared the ability of donor NK cells in the GVHD and non-GVHD setting to control CMV replication. Sorted CD4+ T cells were used to induce GVHD and the associated NK-cell defect because CD4+ T cells do not contribute to CMV control early after infection (M.A.D.-E., University of Western Australia and Lions Eye Institute, oral communication, December 2014). BMT recipients were infected with murine CMV (MCMV) and viral loads were measured. Viral loads were significantly higher in mice with GVHD compared with non-GVHD mice, in both the spleen and liver (Figure 7F). Depletion of NK cells from mice without GVHD increased viral loads in spleen and liver, consistent with the protection afforded by these effectors. In GVHD mice depleted of NK cells, viral loads were increased compared with their nondepleted counterparts to levels equal to those observed in NK-cell–depleted non-GVHD mice (Figure 7F). Thus, the GVHD-induced NK-cell defects after BMT compromise both leukemia and pathogen-specific immunity.

Discussion

The control of viral reactivation and antitumor immunity posttransplant is intimately linked with the function of donor T cells and NK cells. Previous studies have investigated the contributions of these cells in isolation, but have not considered the reciprocal effects they might have on each other during reconstitution after BMT. Here, we show that during GVHD, donor T cells impair donor NK-cell reconstitution through competition for the critical survival/differentiation cytokine IL-15. Importantly, inhibition of donor T-cell proliferation/activation by pharmacological immunosuppression, or provision of IL-15, could restore NK-cell numbers. The donor NK-cell defect observed during GVHD results in compromised control of leukemia and murine CMV infection. Taken together, this study demonstrates the negative impact that alloreactive donor T cells have on NK-dependent control of transplant complications that, to our knowledge, has not previously been functionally demonstrated.

NK cells, derived from the donor graft, are generally restored to pretransplant levels within the first month following allogeneic transplantation30 and contribute to early protection from opportunistic infections. The majority of expanding NK cells are derived from progenitor cells within the graft, and reconstitution is faster in recipients of TCD grafts compared with grafts that are not (ie, TCRαβ-depleted vs CD34-selected).31 The expansion of NK cells is exaggerated in recipients of haploidentical TCD grafts32,33 who, in the absence of donor T cells, do not develop GVHD, supporting our finding that donor T cells impact on NK-cell recovery after BMT. In our studies, reconstitution of NK cells was highly corrupted in the presence of an allogeneic T-cell response. The effect of donor T cells on NK-cell reconstitution and function is difficult to ascertain in the clinic because of concomitant and confounding variables, such as the administration of immune suppression and GVHD. The presence of donor T cells in stem cell grafts has been associated with enhanced NK-cell maturation and acquisition of IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxic capacity.33-35 The ability of donor T cells to enhance early NK-cell functional maturation in the clinic is unclear, but may be related to the provision of relevant cytokines such as IL-2, IL-12, or IL-18 from numerous sources.36 This is in contrast to the impact of GVHD on NK-cell numbers, where a clear deficiency exists37,38 and indeed NK-cell deficiency has been suggested as a biomarker for GVHD,39 although mechanisms are hitherto unknown. Our data show that during GVHD, competition between alloreactive T cells and NK cells for IL-15 results in impaired reconstitution of donor NK cells, with most remaining being early immature NK cells that are known to survive at low levels of IL-15.5

In clinical BMT, CMV reactivation is determined by serological status, the use of mismatched and unrelated donors, and the presence of GVHD.40 Although relapse and CMV reactivation are problematic after TCD BMT, a clear role for NK cells has been established in TCD-haploidentical BMT in relation to killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor disparities between donor and recipient, and in response to AML.41,42 Although CD8 T cells are clearly important in GVL effects, malignancies refractory to T-cell control exist and in situations where MHC expression is modified, NK cells may be particularly relevant.43 Our study demonstrated that NK cells are indeed essential for both GVL and CMV control. Somewhat surprisingly, CMV responses may have beneficial effects on GVL because early CMV reactivation after transplant has been associated with a decreased risk of AML relapse.44,45 The relevant mechanisms remain unknown, but CMV reactivation may induce an inflammatory environment that enhances NK-cell functionality and consequently improves antileukemic effects.46-49

An emerging body of evidence has highlighted the role of autophagy in NK-cell differentiation and function. Autophagy is active in iNK cells, but not NK precursors or mature NK cells, and promotes NK-cell differentiation.50 Sun and colleagues recently demonstrated a role for mitophagy in protecting MCMV-specific memory NK cells from apoptosis.28 We show that in donor NK cells from mice with GVHD, autophagy is exaggerated, which likely accounts for the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria also observed in this setting. We also show that treatment with IL-15 complexes rescues the NK-cell defect in an autophagy-dependent manner. Although inhibition of mechanistic target of rapamycin can initiate autophagy, a recent study by Wang and colleagues showed that in NK cells autophagy is dependent on FoxO1.50 Here, we observed NK-cell expansion following rapamycin treatment, but attribute this to inhibitory effects of rapamycin on donor T cells and sparing of IL-15.

A number of clinical trials are under way utilizing different approaches to isolate, activate, and expand NK cells as immunotherapeutics after BMT and in patients with myeloid malignancies. Theoretically, this approach provides an attractive therapeutic strategy to generate GVL effects in the absence of GVHD. These protocols involve ex vivo stimulation/expansion and adoptive transfer of alloreactive NK cells, together with careful screening and selection of donor NK cells based on inhibitory KIR mismatch with the recipient.41,42,51-54 Previous studies investigated the use of NK-cell adoptive transfer prior to IL-2 administration in patients, but this resulted in expansion of regulatory T cells and a high level of AML relapse.55 Therefore, ex vivo activation of NK cells with a combination of IL-12, IL-15, and/or IL-18 followed by adoptive transfer has been proposed to eliminate the bystander effects on other cell populations, such as regulatory T cells. In support of this approach, a correlation was found between the level of leukemia clearance and the survival and expansion of transferred NK cells.12 Genetic manipulation of transferred NK cells is also being explored clinically.12 However, limited in vivo survival, lack of antigen specificity and the potential for NK-cell exhaustion12,56 may limit these approaches, and results of clinical studies are eagerly awaited.

In the BMT setting, administration of cytokines with activity on both conventional T cells and NK cells posttransplant is likely to promote GVHD. IL-15, like high dose IL-2, is likely to drive acute GVHD via effects on conventional CD8 T cells.57,58 Although the in vitro expansion, activation, and adoptive transfer of NK cells is an attractive therapeutic approach, early studies have already suggested the capability to invoke GVHD via donor T-cell activation in patients not receiving immune suppression.59

Our study highlights the clinical need for recognition that the presence of GVHD precludes an effective NK-cell–dependent leukemia and pathogen-specific response that no doubt contributes to poor outcomes. The effective prevention of alloreactive T-cell responses and the consequent consumption of IL-15 is paramount to preventing this important innate immune deficiency and should be the focus of clinical studies. Once significant GVHD is present, NK-cell reconstitution will require effective interruption of IL-15 consumption by donor T cells, which may be achieved by immune suppression or alloreactive T-cell depletion, with or without subsequent exogenous IL-15 supplementation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Michelle Teng for her critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by research grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC). F.S.-F.-G. was supported by a NH&MRC Early Career Research Fellowship and National Breast Cancer Foundation Fellowship. S.W.L. was supported by a NH&MRC Career Development Fellowship. M.A.D.-E. was a NH&MRC Principal Research Fellow. M.J.S. and G.R.H. were NH&MRC Senior Principal Research Fellows. G.R.H. was a QLD Health Senior Clinical Research Fellow. B.R.B. was supported by National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute grant R01 CA72669.

Authorship

Contribution: M.D.B. designed and performed experiments, analyzed/interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; A.V. performed experiments, analyzed/interpreted data, and edited the manuscript; F.S.-F.-G., M.J.S., and S.W.L. designed experiments, provided and/or generated critical reagents, contributed to discussions, and reviewed the manuscript; I.S.S. and K.E.L. performed experiments and analyzed/interpreted data; R.D.K., K.R.L., and P.F. performed experiments; K.P.A.M., B.R.B., and N.D.H. provided critical reagents and edited the manuscript; S.-K.T. contributed to discussions and reviewed the manuscript; M.A.D.-E. designed experiments, analyzed/interpreted data, provided critical reagents, and assisted with writing the manuscript; and G.R.H. designed experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Geoffrey R. Hill, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, 300 Herston Rd, Herston, QLD, Australia, 4006; e-mail: geoff.hill@qimrberghofer.edu.au.

![Figure 2. NK-cell subset reconstitution and activation during GVHD. (A) Donor NK-cell subsets (CD27+CD11b−CD43+KLRG1− [iNK], CD27+CD11b+CD43+KLRG1− [M1 NK], CD11b+CD27−CD43+KLRG1+ [M2 NK]) were examined, as indicated, in BM in the B6→B6D2F1 system. Representative dot plots from the BM at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 or 3 independent experiments per time point; n = 8 – 12 per group per time point. (B) Donor NK-cell subsets were examined in the BM in the B6→BALB/b system. Representative dot plots from the BM at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 7-8 per group per time point. (C) Quantitation of donor-derived splenic NK-cell subsets (B6→BALB/b). Mean ± SEM pooled from 1 (day 7) or 2 (day 14 and day 28) independent experiments per time point; n = 3-8 per group per time point. (D) CD69 expression by donor NK cells in the BM, spleen, liver, and lung was assessed at day 7, day 14, and day 28 in the B6→BALB/b model. Representative histograms are shown from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 3-8 per group per time point.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/5/10.1182_blood-2016-08-734020/4/m_blood734020f2.jpeg?Expires=1769312405&Signature=GvU-qEeV6m1xr87rnBLo3PanSxNfr0s8vffquMV4h7fy~6d7ftTEwM-8Wb6q-X44IZ~Cs7LtOuG5g1rx2QYwxaKDVXPCRhwXqqrgjQEIx16MZBl6vDwwz556~SraTZCYiOnsjaOdfeluI-vDgs2HzxVOlrf7NDkGk0dN3uVRs-5NVvoAJ22-KrW4q60ZuBWIVu9RQK9pYlSUQxyqinl9dAhpAVPDzOubg2ynJJXh-LU7Cq8x736DgYzKoJtcbpwnAvYGl8ryglmqPG~Kt50BPepHmweaFJX0zebR9y5BHTVg9H-ogwcho00GA0CEsd085tLWc2KvE9MZBGyyCg2jFw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. NK-cell subset reconstitution and activation during GVHD. (A) Donor NK-cell subsets (CD27+CD11b−CD43+KLRG1− [iNK], CD27+CD11b+CD43+KLRG1− [M1 NK], CD11b+CD27−CD43+KLRG1+ [M2 NK]) were examined, as indicated, in BM in the B6→B6D2F1 system. Representative dot plots from the BM at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 or 3 independent experiments per time point; n = 8 – 12 per group per time point. (B) Donor NK-cell subsets were examined in the BM in the B6→BALB/b system. Representative dot plots from the BM at day 14 posttransplant are shown. Mean ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 7-8 per group per time point. (C) Quantitation of donor-derived splenic NK-cell subsets (B6→BALB/b). Mean ± SEM pooled from 1 (day 7) or 2 (day 14 and day 28) independent experiments per time point; n = 3-8 per group per time point. (D) CD69 expression by donor NK cells in the BM, spleen, liver, and lung was assessed at day 7, day 14, and day 28 in the B6→BALB/b model. Representative histograms are shown from 2 independent experiments per time point; n = 3-8 per group per time point.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/5/10.1182_blood-2016-08-734020/4/m_blood734020f2.jpeg?Expires=1770655655&Signature=VZ1rOk1DC1FlOCcK~MOraQI3-gL2ahYeDwQ5ZlAlKR8Ind9Mokg3aZ9yTBsDxfFl-0nZaSzPEBrTqmdgnWSuwv~i~FlRfDxNTr2MsxAGuReUbVNseGqrRI2IcTj-WRMNjTPRvke8hrzw1hTzTnCQE8X6oIIfCgaixovXqC9Gla6Yo2vpJPcxThNHlxafqE5-XbuMUXfvD7s-1vdlhdB-Z8YQSO9xHo2DLNjmdVjTeki7~JFmT32GVwy2y1tehsz8Y9ONliX5o4Te9dXReHcfWJvEUn93sLBfjXDiXRYlp6DGTwBDqEJRmgv0H1EQWWabDovNEm0c7Dn0H1wPobsC-Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)